Abstract

In the FAST Act of 2018, Congress permanently expanded Medicare payment for telemedicine consultations for acute stroke (“telestroke”) from delivery only in rural areas to both urban and rural areas, effective January 2019. Using a controlled time-series analysis, we find that one year after FAST Act implementation, billing for Medicare telestroke increased substantially in Emergency Departments at both directly-affected urban hospitals and indirectly-affected rural hospitals. Nevertheless, one year after FAST Act implementation, only a minority of hospitals with known telestroke capacity had ever billed Medicare for that service and there was substantial billing inconsistent with Medicare requirements. As Congress considers options for post-pandemic Medicare telemedicine payment, our findings--consistent with provider confusion regarding telemedicine billing requirements--suggest simplified payment rules would help ensure expanded reimbursement achieves its intended impact.

Introduction

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare telemedicine reimbursement was largely limited to services provided for rural residents.1 In response to the pandemic, Medicare and other payors temporarily expanded reimbursement for telemedicine to all beneficiaries, both rural and urban.2

Which telemedicine services should be reimbursed post-pandemic is being debated in the Congress, in state legislatures, and across private insurers.3 Both patients and clinicians appreciate telemedicine’s convenience and ability to improve access.4–6 However, the Congressional Budget Office and MedPAC are concerned that broad Medicare telemedicine reimbursement expansions may increase spending without commensurate improvements in outcomes.7,8

One potential compromise is to wait and see: continue the temporary expansions for one to two more years, while collecting relevant data; then reassess telemedicine’s impact on spending and quality.9 Another strategy is to maintain Medicare telemedicine reimbursement in urban areas but only for select conditions. For other conditions, reimbursement would revert to pre-pandemic restrictions, which provide for ongoing selection of additional conditions for permanent expansion.

Indeed, Congress has already invoked that provision to permanently expand Medicare telemedicine reimbursement for select conditions. Treatment of acute stroke (henceforth, “telestroke”) was the first. Under the Furthering Access to Stroke Telemedicine (FAST) Act of 2018, Congress expanded Medicare telestroke payment effective January 1, 2019.10 Subsequently Congress applied the same condition-specific, permanent expansion strategy to telemedicine for substance abuse disorder treatment, in the SUPPORT Act of 2019,11 and to telemedicine for mental illness conditions, in the 2020 Consolidated Appropriations Act.12 Condition-specific selective expansions are not unique to Medicare; several states have taken a similar strategy for non-Medicare services.13

The impact of such selective expansions has not been examined. In this paper we examine the selective expansion of telestroke, given it was the first Medicare telemedicine payment to apply to both urban and rural residents, and was implemented over a year before the pandemic. However, it is important to acknowledge several unique aspects of the telestroke expansion that may limit its generalizability. The evidence base demonstrating telestroke’s effectiveness in improving treatment and reducing mortality is particularly robust.14–16 Furthermore, telestroke is a service initiated by an emergency department (ED) provider--not the patient. In addition, survey and other data collected directly from hospitals prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic indicate telestroke was already used by roughly one-third of all US hospitals, including many urban hospitals.17,18 Reimbursement may not have been critical for sustaining these programs.19

In this paper, we used Medicare data to compare billing trends for hospital ED visits for telestroke and a control condition, behavioral health (“telepsychiatry”). For urban EDs, the FAST Act, expanded reimbursement for telestroke but did not expand reimbursement for telepsychiatry. This telestroke-telepsychiatry comparison accounts for secular changes in telehealth use that may have occurred over the study period. We also examine the impact of Medicare’s temporary expansion of telemedicine reimbursement for all conditions that began in March 2020 at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This allowed us to examine evidence of spillover effects from broadening access to telemedicine in general even though telestroke reimbursement had already been expanded prior to that point.

METHODS

Overview

We studied Medicare fee-for-service claims for the five-year period of January 2016 through March 2021. That time span covered three billing periods for Medicare telestroke: Pre-FAST Act (2016–18), FAST Act (January 1 2019 – February 29, 2020), and COVID-19 Pandemic (March 1, 2020 - March 31, 2021). We contrasted billing trends for two forms of telemedicine Medicare enrollees commonly receive in emergency departments: telestroke, for those presenting with stroke, and a control service, “telepsychiatry,” for those presenting with acute mental illness. Telepsychiatry reimbursement was limited to rural hospitals until the COVID-19 pandemic period.

Telestroke and Telepsychiatry

Telestroke for acute stroke was introduced in the early 2000s.20 An ED telestroke consultation is a real-time videoconference involving the patient, a remote stroke specialist, and a bedside ED provider. In a typical encounter, the stroke specialist interviews and examines the patient, reviews any brain imaging, determines likely diagnosis and eligibility for a treatment to restore brain blood flow, assesses the need for hospital transfer, and recommends other treatments. Stroke specialists typically work for large regional stroke centers or private telestroke companies.17

Telepsychiatry in the ED also involves three parties: the ED provider, the patient, and a behavioral health specialist. The specialist, typically a psychiatrist, evaluates the patient via videoconference, then gives the ED provider recommendations for appropriate treatment and management.

Hospitals with telestroke or telepsychiatry services typically pay a monthly subscription fee for the specialty care, although some pay a per-consultation fee.21,22

Evolving payment coverage for telestroke and telepsychiatry consultations

Reimbursement for telestroke and telepsychiatry is paid to the outside specialist or “distant provider” who provides the consultation. Distant providers commonly submit a separate professional bill for the consultation, as they would if the service were delivered in-person. The facility hosting the telemedicine service can also submit a separate bill for hosting the telemedicine service using the CPT code Q3014. There are arrangements where a hospital can bill on behalf of the consulting physician.

In the pre-FAST Act period, Medicare paid for telestroke and telepsychiatry services only at rural EDs. Consulting providers could use telemedicine-specific CPT codes, modifier codes, or place of service codes to submit their professional bills.

In the FAST act period, beginning January 2019, telestroke became eligible for reimbursement across all EDs (rural and urban) while telepsychiatry remained reimbursable in rural EDs only. In its guidance to providers, CMS stated that the G0 modifier “be appended on claims for telehealth services that are furnished on or after January 1, 2019, for purposes of diagnosis, evaluation, or treatment of symptoms of an acute stroke. Make certain your billing staff is aware of this new code.”10

In the COVID-19 Pandemic period, Medicare temporarily eliminated the rural restriction for all conditions. Therefore, during this period of our study (March 1, 2020 – March 31, 2021), both telestroke and telepsychiatry were eligible for reimbursement across rural and urban EDs alike. As noted above, in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2020, Congress permanently extended coverage of telepsychiatry after the pandemic-related public health emergency is ended.

Identifying “Episodes” of Acute Treatment of Stroke and Mental Illness

We used inpatient and outpatient claims from acute care and critical access hospitals to identify care episodes by the primary diagnosis for the ED visit, observation stay, or hospital admission: ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIA) (ICD-10 I63-I66, I67.89 and G45) and mental illness conditions (ICD-10 F10-F69, F80-F99). We rolled contiguous inpatient, ED, or observation stay claims into an episode. The episode ends at the point of discharge from the hospital, ED, or observation stay. For example, if a patient with a stroke went to Hospital A’s ED, transferred to Hospital B’s ED, and then was hospitalized at Hospital B, the sequence of claims would be rolled up into a single episode. We categorized each episode based on the first hospital that cared for the patient. We limited our analyses to beneficiaries enrolled in traditional Medicare (parts A and B) during the month their episode started.

Identifying episodes that involved a telestroke or telepsychiatry consultation

We employed a two-step process to identify telestroke/telepsychiatry consultations. First, we identified telemedicine consultations using Medicare’s list of telemedicine-specific HCPCS/CPT codes (G0406-8, G0425-7, G0508-9), modifier codes (GT, 95 or G0) or place of service code (“02”) in the Carrier (“professional”) line file.

Second, we defined telestroke/telepsychiatry consultations as telemedicine consultations on claims billed within one day (+/− 1 day) of the start of a beneficiary’s episode of care and that met the following criteria. For acute stroke episodes, a telemedicine consultation was telestroke if (a) was submitted by a neurologist (provider specialty code “13”), (b) had the G0 modifier code (telestroke-specific modifier code), (c) had a diagnosis code for stroke or transient ischemic attack, or (d) was submitted on the same claim as the ED visit. For mental illness episodes, we identified telepsychiatry if the consultation (a) was submitted by a psychiatrist (provider specialty code “26”), (b) had a diagnosis code for mental illness, or (c) was submitted on the same claim as the ED visit. It is rare (1.5% of all consultations), but some facilities will submit telemedicine consultations on the same claim as the ED visit.

Hospital characteristics

Using the hospital’s physical address we categorized each hospital into rural vs. urban using Medicare’s rural definition. Hospital address information was obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey database.

External database of ED telestroke capacity

Medicare data only capture telemedicine consultations submitted for reimbursement. Clinicians may not submit telestroke and telepsychiatry claims for several reasons. For example, volume may be too low to justify the effort in setting up the administrative structure in a setting where the specialists’ time is already supported by other means (e.g., hospital is already paying a monthly fee). To understand how frequently hospitals with telestroke capacity billed for telestroke, we used a previously-created database of 1300 hospitals with known telestroke capacity.17 The database was compiled from academic and non-academic networks and private telemedicine companies who directly provided our research team with a list of hospitals for which they conduct telestroke consults and the date those services were first introduced. For a subset of hospitals we also received the number of telestroke consultations per month across all payers (Medicare and non-Medicare).

Among these hospitals in this database, we focused on the 1,166 hospitals, both rural and urban, with telestroke capacity as of January 2018, 12 months prior to the implementation of the FAST Act. In each of the hospitals, we quantified whether there were any stroke episodes with a Medicare telestroke consultation from the start of our study period (January 2016) through the end of 2018, 2019, and 2020. This analysis measured the extent of under-billing of telemedicine by clinicians and hospitals.

Analyses

We calculated and plotted the percent of stroke and mental health episodes in a given month with an associated telemedicine consultation. To measure the impact of the FAST Act on telestroke billing, we conducted an interrupted time series analysis to estimate changes in telemedicine claims among stroke and mental illness episodes across the study period. We used a segmented linear regression model23,24 with splines to assess changes from the pre-FAST act period (2016–2018) to the FAST Act period (January 2019 to February 2020) and the COVID-19 pandemic period (March 2020 to March 2021) (see the Supplemental Appendix for more details).25 This model allowed us to characterize each period by how much the intercept changed (a.k.a., the level change) and by how much the monthly rate of growth changed from the prior period (a.k.a., the incremental rate of growth). We report both the absolute change and the relative change in use of telemedicine, which we report in percentages alongside the model estimates (95% confidence intervals for the estimates and relative changes are provided in the Supplemental Appendix25). To assess differences in trends between rural and urban hospital episodes, we estimated an analogous segmented regression model that included interactions with an indicator for rural (vs. urban) hospital.

We ran all models in Stata version 17. Harvard Medical School IRB granted approval for this study. Patient informed consent was not required given the data was de-identified.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we do not study patients with primary diagnoses other than acute stroke/TIA or mental illness, nor do we study patients cared for in facilities other than hospital EDs. This strategy helped us maintain a cleaner definition of telestroke and telepsychiatry, but this strategy may have also excluded some relevant episodes. For example, we would exclude a patient who presented with weakness who receives a telemedicine consultation for concern of acute stroke, but is ultimately diagnosed with another condition. Second, to identify telestroke and telepsychiatry consultations, we identified professional telemedicine claims that took place during the episode of care. While we implemented a number of checks described above, it is possible that some of the telemedicine consultations identified were not actually instances of telestroke or telepsychiatry. Third, it is important to emphasize we are capturing telemedicine billing and not the actual use of telemedicine consultations. Our analysis of billing at hospitals with known telestroke capacity, below, highlights that many Medicare telestroke consultations likely did not result in a telemedicine bill. Fourth, our analyses focus on two applications of hospital-based telemedicine – acute treatment of stroke and mental illness. The generalizability of these patterns to other applications, in particular clinic consultations outside the ED, is unknown. Finally, we examined the selective expansion of Medicare telemedicine prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is unclear whether the findings of this selective expansion generalize to the current situation, where telemedicine is reimbursed widely, and there is policy debate on whether to restrict telemedicine to select conditions after the COVID-19 health emergency ends; moreover, even if a policy of selective expansion is pursued moving forward, it will be under much-changed circumstances.

RESULTS

From January 1, 2016, through March 31, 2021, there were 1,832,094 stroke and 3,694,397 mental illness episodes in 4,420 and 4,751 hospitals respectively.

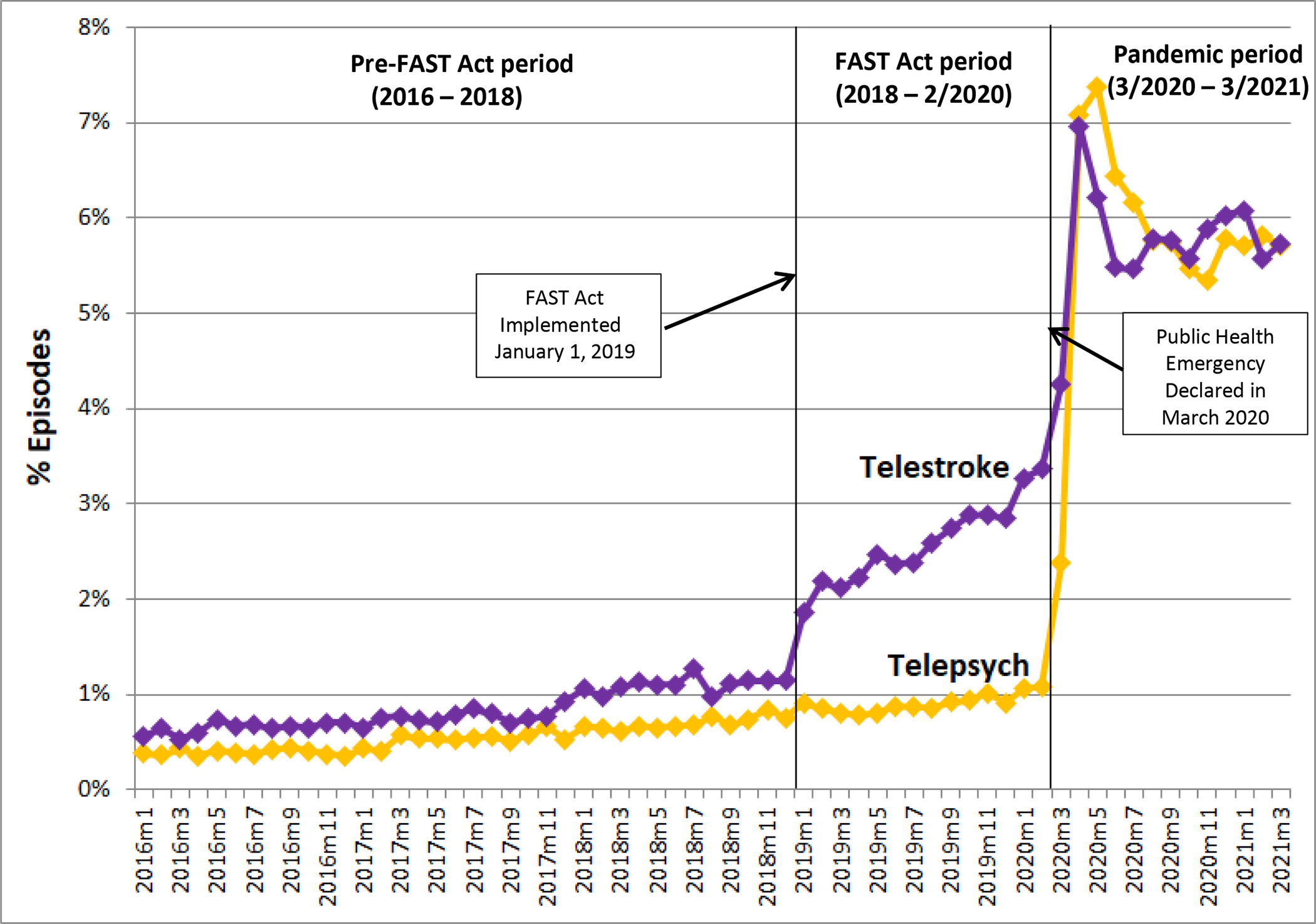

Differential changes in telemedicine claims after the FAST act was implemented

The FAST Act went into effect in January 2019. The fraction of all stroke episodes with a telestroke claim more than doubled (1.1% in December 2018, or 347/30,210 strokes had a telestroke, to 2.8% December 2019, or 835/29,358 strokes had a telestroke (Exhibit 1)). In our model, relative to the yearly rate of growth pre-FAST Act and relative to growth of telepsychiatry, telestroke grew by 476% during the FAST act period (Exhibit 2, p<.001).

Exhibit 1.

Percent of episodes for acute stroke and acute mental illness associated with a billed Emergency Department Medicare telemedicine consultation, January 2016 to March 2021

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of a 100% sample of fee-for-service Medicare claim records, January 2016 through March 2021. NOTES: FAST Act = Furthering Access to Stroke Telemedicine (FAST) Act of 2018. ED = Emergency Department. During the pre-FAST Act period, only care in rural communities was eligible for telemedicine reimbursement. During the FAST Act period, telestroke was eligible in both rural and urban communities, while telepsychiatry remained eligible only in rural communities. During the Pandemic period, all telemedicine visits were eligible for reimbursement.

Exhibit 2.

Estimated changes in Medicare ED telestroke and ED telepsychiatry billing after payment expansions

| ED Telestroke Claims (N=1,832,094 acute stroke episodes) | ED Telepsychiatry Claims (N=3,694,397 acute mental illness episodes) | Difference Between ED Telestroke & ED Telepsychiatry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Study Period (dates) | Estimate (% episodes with telemedicine consultation) | Change Relative to Prior Period | Estimate (% episodes with telemedicine consultation) | Change Relative to Prior Period | Estimate (% episodes with telemedicine consultation) | Change Relative to Prior Period |

|

| ||||||

| Pre-FAST Act Period (January 2016 – December 2018) | ||||||

| Baseline telemedicine billing rate | 0.51% | -- | 0.31% | -- | 0.19% | -- |

| Yearly rate of growth during period | 0.21% | 0.15% | 0.07% | |||

| FAST Act Period (January 2019 – February 2020) | ||||||

| Period change in billing rate | 0.67% | 131% | 0.02% | 6% | 0.65% | 127% |

| Yearly rate of growth during period | 1.00% | 476% | 0.06% | 40% | 0.94% | 448% |

| Pandemic Period (March 2020 – March 2021) | ||||||

| Period change in billing rate | 2.30% | 194% | 4.53% | 1349% | −2.24% | −193% |

| Yearly rate of growth during period | −0.89% | −72% | 0.12% | 57% | −1.00% | −83% |

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of a 100% sample of fee-for-service Medicare claim records over the period January 2016 through March 2021. NOTES: FAST Act = Furthering Access to Stroke Telemedicine (FAST) Act of 2018. ED = Emergency Department. During the pre-FAST Act period, only care in rural communities was eligible for telemedicine reimbursement. During the FAST Act period, telestroke was eligible in both rural and urban communities, while telepsychiatry remained eligible only in rural communities. During the Pandemic period, all telemedicine visits were eligible for reimbursement. 95% confidence intervals for the estimates are included in the Supplemental Appendix.

The implementation of the FAST Act expanded reimbursement for telestroke to urban hospitals; rural hospitals were already eligible for reimbursement. Even so, we observed similar increases in telestroke claims in both urban and rural hospitals during the FAST Act period (Exhibit 3). There was no significant difference in the period change or the yearly rate of growth between rural and urban hospitals (p-values: level shift p=.88, growth rate p=.16)(see the supplemental appendix for full model details).25

Exhibit 3.

Percent of rural and urban hospital episodes for stroke and acute mental illness with a billed ED Medicare telemedicine consultation, January 2016 to March 2021

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of a 100% sample of fee-for-service Medicare claim records over the period January 2016 through March 2021. NOTES: FAST Act = Furthering Access to Stroke Telemedicine (FAST) Act of 2018. ED = Emergency Department. During the pre-FAST Act period, only care in rural communities was eligible for telemedicine reimbursement. During the FAST Act period, telestroke was eligible in both rural and urban communities, while telepsychiatry remained eligible only in rural communities. During the Pandemic period, all telemedicine visits were eligible for reimbursement.

Changes in telestroke and telepsychiatry claims after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

After the pandemic began in March 2020, the fractions of stroke and acute mental illness episodes with an associated Medicare telemedicine claim increased dramatically (Exhibit 1). Between February 2020 and April 2020, episodes with telestroke claims increased 3.6 percentage points (over 100% increase), and episodes with telepsychiatry claims increased 6.0 percentage points (over 500% increase). After this initial peak in telemedicine claims per episode, the upward trend for both telestroke and telepsychiatry decreased. Similar patterns were observed among episodes starting in rural and urban hospitals (Exhibit 2).

Accuracy of billing for telestroke

By statute in the pre-FAST Act era (2016–2018), telemedicine reimbursement was limited to rural hospitals. However, we still observed substantial telestroke and telepsychiatry use at urban hospitals during this period (Exhibit 2). We linked 55% of all telestroke claims (5,111/9,249) and 41% of all telepsychiatry claims (8,028/19,676) were at an urban hospital in the pre-FAST Act period.

We also observed considerable variety in the telemedicine codes used to bill for telestroke (Exhibit 4). After the FAST Act was implemented in January 2019, per Medicare’s guidance,10 telestroke consultations were supposed to use a new G0 modifier code, which was introduced as part of the legislation to specify the consultation was for telestroke. Yet, only 50–60% of the telestroke claims in the post-FAST act period used the G0 modifier code (Exhibit 4). The telestroke consults that did not use the G0 code used various combinations of inpatient telemedicine HCPCS codes, the GT modifier code, the place of service code for “telehealth”, or the 95 modifier code, which was recommended by Medicare for telemedicine services during the COVID-19 pandemic period.26

Exhibit 4.

Stroke episodes with a billed ED Medicare telestroke consultation, by consistency with Medicare billing code regulations a

SOURCE: Authors’ analysis of a 100% sample of fee-for-service Medicare claim records over the period January 2016 through March 2021. NOTES: FAST Act = Furthering Access to Stroke Telemedicine (FAST) Act of 2018. ED = Emergency Department. a As part of the FAST Act legislation, the HCPCS modifier code “G0” was introduced for use beginning in January 2019, to indicate/verify the professional consultation billed was for Medicare telestroke (i.e., was a telemedicine consultation for acute stroke reimbursible under current regulations). “Consistent” Medicare telestroke claims included the “G0” modifier. “Inconsistent” telestroke claims did not include the “G0” modifier, instead providing another telemedicine code in its place (HCPCS/CPT codes G0406–8, G0425–7, G0508–9; modifier codes GT, 95; or place of service code “02”).

Fraction of hospitals with known telestroke capacity that submitted a bill for a telestroke consultation

Among the 1,166 hospitals with known telestroke capacity before 2018, 27% had any Medicare telestroke claims by the end of 2018 (prior to and gearing up for FAST Act implementation) and 39% had any Medicare telestroke claims by the end of 2019 (within one year of FAST Act implementation). By the end of 2020, 7 months into the COVID-19 pandemic period, 60% of these hospitals had any Medicare telestroke claims.

DISCUSSION

There is active debate on whether and how Medicare and other payors should permanently expand coverage of telemedicine use after the COVID-19 pandemic. For Medicare, one option being considered is to permanently continue telemedicine reimbursement for services delivered at both rural and urban locations but only for select conditions. That is, the approach to payment prior to the COVID-19 emergency would largely resume with the expectation that the number of conditions covered in urban areas would slowly expand.

The current study advances the literature by examining billing trends in Medicare telestroke (i.e., telemedicine for acute stroke), the first condition for which Medicare payment in urban areas was selectively expanded. In the first year after implementation, the FAST Act was associated with a more than doubling in Medicare telestroke billing. This should be viewed as a success of the legislation, as it demonstrates that clinicians and telestroke organizations responded quickly to recognition of its potential to improve care for acute stroke.

At the same time, our analyses highlight critical nuances in the response to selective expansion of telestroke. The FAST Act applied directly only to urban hospitals; reimbursement for Medicare telestroke at rural hospitals had already existed for many years. Nevertheless, we found that even before FAST Act implementation, the majority of Medicare telestroke billing came from urban hospitals, and after implementation, similar billing increases were seen at rural and urban sites.

We hypothesize that these patterns were due, in part, to telemedicine billing rules. For example, before the FAST Act, the remote specialist had to know whether the ED at which the patient was located was in a Medicare-designated rural area. After the FAST Act, reimbursement rules were much more straightforward-- it eliminated the need to establish the delivery site was rural. It is also possible that with broader reimbursement, telestroke networks saw greater value in setting up their infrastructure to submit claims.

Our results also highlight substantial underbilling. A third of US hospitals had telestroke capacity as of 2019.17 Based on external data, telestroke consultations were occurring at these hospitals, but in both the year before and in the year after the FAST Act, the majority of hospitals with capacity never had an associated a Medicare telestroke claim. For many hospitals, lack of Medicare reimbursement, is not a critical barrier to implementation. Our findings indicate that, at least for Medicare, claims data likely substantially underestimate the actual number of telestroke consultations.

Why were more clinicians not submitting bills for reimbursement of telestroke? We believe that this was largely due to the complexity of telemedicine billing for hospital-based services, including administrative and contractual barriers. To submit a claim, the remote specialist would need demographic information on a patient, including their insurance plan, and would typically need registration with the health plan for the hospital in which the patient is located. Before the FAST Act, as noted above, a stroke specialist providing telestroke services would also have to know whether the patient was at a rural vs. urban hospital (as defined by Medicare) before submitting a claim. Clinicians can reassign the rights to bill to the organization that operates the originating site ED, but this requires agreements with each of the hospitals at which they provide telestroke. And, if the consulting hospital has relatively few Medicare telestroke consultations per year, it may not be worth the effort to build the administrative system needed to effectively submit claims for them. Moreover, our finding that fewer than half of Medicare telestroke consultations submitted for reimbursement included the appropriate modifier code required for payment (G0) raises concerns regarding the impact of billing complexity on accuracy.

We believe the dramatic growth in billing for both telestroke and telepsychiatry during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when all Medicare telemedicine was reimbursed regardless of rural or urban delivery, speaks to the potential negative impacts of high complexity and administrative barriers on Medicare telemedicine billing. While increased clinical need for telemedicine certainly played an important role in this growth, we hypothesize it was also facilitated by the removal of many administrative barriers, such as: condition-specific telemedicine rules, state licensure requirements, and waiving of privacy requirements for technology. Together these changes created a simpler landscape for clinicians and revenue cycle staff, where all forms of telemedicine were covered.

Policy implications

Our results highlight that selective Medicare telehealth reimbursement expansions alone may have a limited impact, given the many other regulatory and structural barriers to submitting bills that would not be addressed.

In the Medicare claims, we observed a substantial number of telemedicine consultations that did not follow Medicare billing criteria. Among these were claims that did not follow CMS guidance to use a G0 modifier code to indicate a telestroke was delivered, as well as submission of telestroke claims by urban hospitals before reimbursement in that setting took effect. While Medicare could develop processes to reject these claims to save money, we believe this is the wrong strategy. We hypothesize that this erroneous billing was largely due to confusion among clinicians and revenue cycle staff, and the more appropriate strategy would be to simplify how telemedicine consultations are billed.

Greater complexity is one downside of selective reimbursement of telemedicine to specific conditions. In contrast to universal coverage, in an environment with selective reimbursement, clinicians will have to remember which conditions and diagnoses are reimbursable. Moreover, that information will be subject to change as evidence concerning cost-effectiveness accumulates. This layer of complexity could discourage Medicare telemedicine uptake by clinicians. However, as noted above, one consequence of universal telehealth reimbursement may be more low-value care – increases in utilization and spending without commensurate improvements in health.

Medicare does not need to pay for telestroke and other telemedicine services via fee-for-service payments. A simpler and potentially more successful strategy for Medicare might be to provide smaller, rural hospitals (whose patients would benefit most from telestroke capacity), a monthly or yearly payment to have this capacity in place.

Finally, our results emphasize the importance of spillovers which could have access implications for rural residents. Specifically, excluding urban areas from telemedicine reimbursement may dampen the provision of telemedicine, and thereby access to those services, in rural areas--much as it appeared to do in the current study.

Conclusion

The FAST Act selectively expanded Medicare reimbursement of telestroke for stroke patients, starting in January 2019. We find this legislation was associated a substantial initial response, and continued growth of billing for Medicare telestroke in the urban hospitals directly targeted by the reform, as well as with increased billing for the service in rural hospitals where reimbursement was already allowed. Our results highlight that selective expansion of Medicare telemedicine reimbursement for a specific condition, such as the expansion of telestroke payment under the FAST Act, can be successful in expanding beneficial health services, and may spill over in the form of increased utilization of already-reimbursable telemedicine services. However, we found substantial under-billing and erroneous billing associated with telestroke expansion, which we believe is secondary to the complexity of current telemedicine reimbursement policies. Our findings suggest that, in shaping the future of Medicare telemedicine payment, simplifying payment rules would help ensure that expanded reimbursement improves access to timely, effective care.

Supplementary Material

Funding Information:

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (1R01MH112829) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS111952)

Endnotes

- 1.Tuckson RV, Edmunds M and Hodgkins ML, 2017. Telehealth . New England Journal of Medicine, 377(16), pp.1585–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verma S “Early Impact Of CMS Expansion Of Medicare Telehealth During COVID-19,” Health Affairs Blog, July 15, 2020. DOI: 10.1377/hblog20200715.454789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra A, Bhatia RS, Snoswell CL. Paying for Telemedicine After the Pandemic. JAMA. 2021;325(5):431–432. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramaswamy A, Yu M, Drangsholt S, Ng E, Culligan PJ, Schlegel PN, Hu JC. Patient Satisfaction With Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Cohort Study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(9):e20786. doi: 10.2196/20786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uscher-Pines L, Lori, et al. “Suddenly becoming a “virtual doctor”: Experiences of psychiatrists transitioning to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Psychiatric Services 71.11 (2020): 1143–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malouff TD, et al. Physician Satisfaction With Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mayo Clinic Florida Experience. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021. Aug;5(4):771–782. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Congressional Budget Office Blog. Telemedicine. (Accessed April 28, 2021 at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50680)

- 8.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. March 2021 Report to Congress. Telehealth in Medicare after the coronavirus public health emergency. (Accessed April 28, 2021 at http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar21_medpac_report_to_the_congress_sec.pdf)

- 9.117th Congress. Ways and Means Health Subcommittee on Charting the Path Forward for Telehealth. Testimony of Ateev Mehrotra April 28, 2021. (Accessed August 11, 2021 at https://waysandmeans.house.gov/legislation/hearings/health-subcommittee-hearing-charting-path-forward-telehealth)

- 10.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MLN 10883, “New Modifier for Expanding the Use of Telehealth for Individuals with Stroke”. (Accessed August 11, 2021 at https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/MM10883.pdf)

- 11.The National Law Review. SUPPORT Act Expands Telehealth Treatment for Substance Use Disorders. October 25, 2018. (Accessed April 28, 2021 at https://www.natlawreview.com/article/support-act-expands-telehealth-treatment-substance-use-disorders)

- 12.Center for Connected Health Policy. Telehealth Provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (HR 133). January 2021. (Accessed April 28, 2021 at https://cchp.nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/files/2021-01/Appropriations%20Act%20HR%20133%20Fact%20Sheet%20FINAL.pdf)

- 13.Office of Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker Press Release. Governor Baker Signs Health Care Legislation Increasing Access to Quality, Affordable Care, Promoting Telehealth and Protecting Access To COVID-19 Testing, Treatment. January 1, 2021. (Accessed April 21, 2021 at https://www.mass.gov/news/governor-baker-signs-health-care-legislation-increasing-access-to-quality-affordable-care)

- 14.Schwamm LH, Holloway RG, Amarenco P, et al. A review of the evidence for the use of telemedicine within stroke systems of care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009. Jul;40(7):2616–34. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwamm LH, Audebert HJ, Amarenco P, et al. Recommendations for the implementation of telemedicine within stroke systems of care: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009. Jul;40(7):2635–60. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcock AD, Schwamm LH, Zubizarreta JR, et al. Reperfusion Treatment and Stroke Outcomes in Hospitals With Telestroke Capacity. JAMA Neurol. Published online March 01, 2021. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richard JV, Wilcock AD, Schwamm LH, et al. Assessment of Telestroke Capacity in US Hospitals. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):1035–1037. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zachrison KS, Boggs KM, M Hayden E, et al. A national survey of telemedicine use by US emergency departments. J Telemed Telecare. 2020. Jun;26(5):278–284. doi: 10.1177/1357633X18816112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D,Wang G, Zhu W, et al. Expansion of telestroke services improves quality of care provided in super rural areas. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(12):2005–2013. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma R, Zachrison KS, Viswanathan A, et al. Trends in Telestroke Care Delivery: A 15-Year Experience of an Academic Hub and Its Network of Spokes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020. Mar;13(3):e005903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zachrison KS, Richard JV, Mehrotra A. Paying for Telemedicine in Smaller Rural Hospitals: Extending the Technology to Those Who Benefit Most. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(8):e211570. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKinney AC, Ward MM, Ullrich F, Ayyagari P, Bell AL, Mueller KJ. The Business Case for Tele-emergency. Telemed J E Health. 2015. Dec;21(12):1005–11. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F and Ross-Degnan D, 2002. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics, 27(4), pp.299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Penfold RB and Zhang F, 2013. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Academic pediatrics, 13(6), pp.S38–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.To access the appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MLN SE20011, “Medicare FFS Response to the PHE on the COVID-19”. (Accessed August 11, 2021 at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/se20011.pdf)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.