Abstract

During the COVID-19, healthcare workers are exposed to a higher risk of mental health problems, especially anxiety symptoms. The current work aims at contributing to an update of anxiety prevalence in this population by conducting a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Medline and Pubmed were searched for studies on the prevalence of anxiety in health care workers published from December 1, 2019 to September 15, 2020. In total, 71 studies were included in this study. The pooled prevalence of anxiety in healthcare workers was 25% (95% CI: 21%–29%), 27% in nurses (95% CI: 20%–34%), 17% in medical doctors (95% CI: 12%–22%) and 43% in frontline healthcare workers (95% CI: 25%–62%). Our results suggest that healthcare workers are experiencing significant levels of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially those on the frontline and nurses. However, international longitudinal studies are needed to fully understand the impact of the pandemic on healthcare workers’ mental health, especially those working at the frontline.

Keywords: Health care workers, Anxiety, Professional categories, COVID-19

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has led to an increment of psychological distress levels in the general population. Some contributing risk factors for this increment are the unpredictable nature of the disease, home isolation and confinement, a lack of clarity from leaders regarding the seriousness of the risk, or the emotional contagion between individuals (Huremović, 2019). The psychological impact has been reported to be especially high in healthcare workers (HCW), who face additional group-specific stressors (Cheng and Li Ping Wah-Pun Sin, 2020; C. Zhang et al., 2020b). Very intense work-related stressors include long working hours, strict instructions and safety measures, a permanent need for concentration and vigilance, reduced social contact, and the performance of tasks which they may not have been prepared for (Vieta et al., 2020).

This emotional distress experienced by HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic has been significantly associated with depression, stress and anxiety (Elbay et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020), with anxiety being frequently observed in HCW (Garcia-Iglesias et al., 2020). Recent studies have shown that frontline HCW may be experiencing the highest levels of anxiety (Buselli et al., 2020), because they are usually responsible for the care of patients with COVID-19, and more mentally overwhelmed by the lack of specific treatment guidelines or adequate support (Liu et al., 2020b). A previous study reported that nurses with a higher level of stress were more likely to develop anxiety (Mo et al., 2020) and HCW women seem also to be at higher risk for anxiety (Babore et al., 2020).

Three systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported prevalence rates of anxiety among HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first, based on 13 cross-sectional studies, reported an overall prevalence of 23.2% (Pappa et al., 2020). The second meta-analysis included seven studies from China and reported an increased risk of anxiety among HCW (OR=1.32, 95%CI=1.09–1.6) compared with other professionals (da Silva and Neto, 2021). The third study found that the prevalence of anxiety and depression was similar among HCW and the general population (33%), but higher among patients with pre-existing conditions and COVID-19 infection (55%) (Luo et al., 2020). These systematic reviews and meta-analyses were conducted in April/May 2020. Since then, there has been a growing number of studies analyzing the prevalence of anxiety in HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the current meta-analysis aims to update the evidence on the prevalence of anxiety in HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, and due to the evidence that suggests that the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic might differ across different professional categories, we also investigated the prevalence of anxiety separately for professional groups (i.e., medical doctors, nurses, and frontline HCW).

2. Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Moher et al., 2009) (Table S1).

2.1. Search strategy

Two researchers (JBN and MPM) searched for cross-sectional studies reporting the prevalence of anxiety published from December 1, 2019 through September 15, 2020, using MEDLINE via PubMed. The search strategy was: (covid OR covid-19 OR coronavirus OR "corona virus" OR SARSCoV-2 OR "Coronavirus"[Mesh] OR "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2"[Supplementary Concept] OR "COVID-19"[Supplementary Concept] OR "Coronavirus Infections/epidemiology"[Mesh] OR "Coronavirus Infections/prevention and control"[Mesh] OR "Coronavirus Infections/psychology"[Mesh] OR "Coronavirus Infections/statistics and numerical data"[Mesh]) AND (anxiety OR anxiety symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR anxious OR "Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders"[Mesh] OR "Anxiety"[Mesh] OR "Anxiety Disorders"[Mesh] OR "Anxiety/epidemiology"[Mesh] OR "Anxiety/statistics and numerical data"[Mesh] OR depression OR depressive OR "Depression"[Mesh] OR "Depressive Disorder"[Mesh] OR "Depression/statistics and numerical data"[Mesh]) AND (“health care workers” OR “medical staff” OR “health care professionals” OR “health care workers” OR “health workers” OR “health professionals” OR “health personnel” OR "Health Personnel"[Mesh]). No language restriction was made. References from selected articles were inspected to detect additional potential studies. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus among two more reviewers (JS and BO).

2.2. Selection criteria

Studies were included if they: (1) reported cross-sectional data on the prevalence of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) were focused on samples of HCW; and (3) described the methods used to assess or diagnose anxiety. We excluded abstracts without the full text available and review articles.

A pre-designed data extraction form was used to extract the following information: country, sample size, prevalent rates of anxiety, proportion of women, average age, instruments used to assess anxiety, response rate and sampling methods.

2.3. Methodological quality assessment

Articles were assessed by two independent reviewers (JBN and MPM) for methodological validity before inclusion in the review using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017). Quality was evaluated with a score of zero or one for each of nine criteria: 1) Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target population?; 2) Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way?; 3) Was the sample size adequate?; 4) Were the study subjects and setting described in detail?; 5) Was data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample?; 6) Were valid methods used for the identification of the condition?; 7) Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants?; 8) Was there appropriate statistical analysis?; 9) Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?

Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussions, or by consulting two more reviewers (JS and BO).

2.4. Data extraction and statistical analysis

A generic inverse variance method with a random effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence (DerSimonian and Laird, 1986). Random-effects model attempts to generalize findings beyond the included studies by assuming that the selected studies are random samples from a larger population (Cheung et al., 2012).

The Hedges Q statistic was reported to check heterogeneity across studies, with statistical significance set at p < 0.10. The I 2 statistic and 95% confidence interval was also used to quantify heterogeneity (von Hippel, 2015). I 2 values between 25% and 50% are considered as low, 50%–75% as moderate, and 75% or more as high (Higgins et al., 2003). Heterogeneity of effects between studies occurs when differences in results for the same exposure-disease association cannot be fully explained by sampling variation. Sources of heterogeneity can include differences in study design or demographic characteristics. We performed meta-regression and subgroup analyses (Thompson and Higgins, 2002) to explore sources of heterogeneity expected in meta-analyses of observational studies (Egger et al., 1998). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine the influence of each individual study on the overall result by omitting studies one by one. Publication bias was determined through visual inspection of a funnel plot and also with the Egger's test (Egger et al., 1997) (p value < 0.05 indicates publication bias) since funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method for assessing publication bias in meta-analyses of proportion studies (Hunter et al., 2014).

Statistical analyses were conducted by JS and run with STATA statistical software (version 10.0; College Station, TX, USA) and R (R Core Team, 2019).

3. Results

3.1. Identification and selection of articles

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the literature search strategy and study selection process. Initially, 354 potential records were identified, from which 1 duplicate was removed, 168 were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts for not meeting the inclusion criteria and 2 of them were then excluded because full text was not available. After reading the remaining 184 articles in full, we finally included 71 in our meta-analysis (Almater et al., 2020(Apisarnthanarak et al., 2020; Ayhan Başer et al., 2020; Badahdah et al., 2020; Cai et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020b, Chen et al., 2020c, Chen et al., 2020d; Cheng et al., 2020b; Chew et al., 2020; Civantos et al., 2020; Consolo et al., 2020; Dal’Bosco et al., 2020; Di Tella et al., 2020; Dosil Santamaría et al., 2020; Elbay et al., 2020; Elhadi et al., 2020; Gallopeni et al., 2020; Giusti et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2020a; Gupta et al., 2020b; Huang et al., 2020a; Huang et al., 2020b; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Kannampallil et al., 2020; Keubo et al., 2020; Koksal et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020b; Li et al., 2020b; Liang et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020a, Liu et al., 2020b; Lu et al., 2020; Luceño-Moreno et al., 2020; Magnavita et al., 2020; Mahendran et al., 2020; Naser et al., 2020; Ning et al., 2020; Pouralizadeh et al., 2020; Prasad et al., 2020; Que et al., 2020; Şahin et al., 2020; Salopek-Žiha et al., 2020; Sandesh et al., 2020; Si et al., 2020; Skoda et al., 2020; Stojanov et al., 2020; Suryavanshi et al., 2020; Temsah et al., 2020; Teng et al., 2020; Teo et al., 2020; Tu et al., 2020; Vanni et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020a, Wang et al., 2020b, Wang et al., 2020c, Wang et al., 2020d; Wańkowicz et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020; Xiaoming et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020b; Yang et al., 2020a, Yang et al., 2020b; Yáñez et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020b; Zhang et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020a, Zhu et al., 2020b).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection.

3.2. Characteristics of the included studies

Table 1 shows the characteristics of those studies (n = 59) that reported prevalence rates of anxiety in HCW (without distinction of the type of workers); Table 2 displays characteristics of studies reporting data from nurses (n = 17); Table 3 for medical doctors (n = 13), and Table 4 for frontline HCW (n = 13).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis based on samples of healthcare workers.

| Author (Publication year) | Population | Country | Mean age (SD) | % Females (n) | Sample size (n) | Response rate (%) | Sampling method | Anxiety assessment | Diagnostic Criteria | Prevalence |

Quality assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | |||||||||||

| Apisarnthanarak et al. (2020) | HCW | Thailand | 32 (23-62) | 59.00% (95) | 160 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 19.38% | 31 | 6 |

| Ayhan Başer et al. (2020) | HCW | Turkey | NR | NR | 426 | 98% | NR | BAI | ≥16 | 24.41% | 104 | 7 |

| Badahdah et al. (2020) | HCW | Oman | 37.67 (7.68) | 80.30% (407) | 509 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 25.93% | 132 | 7 |

| Chen et al. (2020b) | HCW | China | 36.54 (8.57) | 68.63% (619) | 902 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 16.63% | 150 | 7 |

| Chen et al. (2020c) | HCW | Ecuador | NR | 34.52% (87) | 252 | 62.84% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 28.17% | 71 | 7 |

| Chen et al., 2020d) | Pediatric HCW | China | 32.6 (6.5) | 90.48% (95) | 105 | 84.68% | NR | SAS | ≥50 | 18.10% | 19 | 7 |

| Cheng etal. (2020b) | Pediatric HCW | China | NR | 82.4% (440) | 534 | NR | Convenience | SAS | ≥50 | 14.00% | 75 | 7 |

| Chew et al. (2020) | HCW | India, Singapore | 29 (NR) | 64.3% (583) | 906 | 90.60% | NR | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 8.72% | 79 | 8 |

| Consolo et al. (2020) | Dental Workers | Italy | NR | 39.6% (141) | 356 | 40.00% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 23.88% | 85 | 7 |

| Di Tella et al. (2020) | HCW | Italy | 42.9 (11.2) | 72.4% (105) | 145 | NR | Convenience | STAI-S | ≥41 | 71.03% | 103 | 6 |

| Dosil Santamaría et al. (2020) | HCW | Spain | 42.8 (10.2) | 80.29% (338) | 421 | NR | Snowball | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 28.74% | 121 | 7 |

| Elbay et al. (2020) | HCW | Turkey | 36.05 (8.69) | 56.8% (251) | 442 | NR | Convenience | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 35.29% | 156 | 7 |

| Elhadi et al. (2020) | HCW | Libya | 33.3 (7.4) | 51.94% (387) | 745 | 93.13% | Convenience | HADS | >10 | 46.71% | 348 | 8 |

| Gallopeni et al. (2020) | HCW | Kosovo | 39 (10.37) | 61.32% (363) | 592 | NR | NR | HADS | >10 | 44.59% | 264 | 7 |

| Giusti et al. (2020) | HCW | Italy | 44.6 (13.5) | 62.42% (206) | 330 | 41.25% | Convenience | STAI-S | ≥40 | 71.20% | 235 | 7 |

| Gupta et al. (2020a) | HCW | Nepal | 29.5 (6.1) | 52.67% (79) | 150 | NR | Snowball | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 10.00% | 15 | 6 |

| Gupta et al. (2020b) | HCW | India | NR | 36.12% (406) | 1124 | 79.45% | Quota | HADS | >7 | 37.19% | 418 | 8 |

| Huang and Zhao (2020) | HCW | China | NR | NR | 2250 | 85.30% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥9 | 35.64% | 802 | 7 |

| Huang et al. (2020a) | HCW | China | NR | 81.30% (187) | 230 | 93.50% | Cluster | SAS | ≥50 | 23.04% | 53 | 8 |

| Huang et al. (2020b) | HCW | China | NR | 58.79% (214) | 364 | 96.55% | Cluster | SAS | ≥50 | 23.35% | 85 | 9 |

| Kannampallil et al. (2020) | HCW | USA | NR | 54.96% (216) | 393 | 28.58% | NR | DASS-21 | ≥8 | 18.58% | 73 | 6 |

| Keubo et al. (2020) | HCW | Cameroon | NR | 54.45% (159) | 292 | NR | Snowball | HADS | >10 | 42.12% | 123 | 6 |

| Koksal et al. (2020) | HCW | Turkey | 35.6 (8.5) | 70.1% (492) | 702 | NR | NR | HADS | >10 | 57.55% | 404 | 7 |

| Lai et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | 76.69% (964) | 1257 | 68.69% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 12.25% | 154 | 8 |

| Li et al. (2020a) | HCW | China | NR | 100% (4369) | 4369 | 82.17% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥8 | 25.20% | 1101 | 8 |

| Liang et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | 81.31% (731) | 899 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 14.24% | 128 | 7 |

| Lin et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | NR | 2316 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | >5 | 41.11% | 952 | 6 |

| Liu et al. (2020b) | HCW | China | NR | 84.57% (433) | 512 | 85.33% | Convenience | SAS | ≥50 | 12.50% | 64 | 8 |

| Liu et al. (2020a) | Pediatric HCW | China | NR | 85.52% (1737) | 2031 | NR | Convenience | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 12.21% | 248 | 7 |

| Lu et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | 77.64% (1785) | 2299 | 94.88% | NR | HAMA | ≥7 | 24.75% | 569 | 8 |

| Magnavita et al. (2020) | HCW | Italy | NR | 70.10% (417) | 595 | 73.46% | Convenience | GADS | ≥5 | 16.64% | 99 | 8 |

| Mahendran et al. (2020) | Dental Workers | China | NR | 72.5% (87) | 120 | 96.00% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 32.50% | 39 | 7 |

| Naser et al. (2020) | HCW | Jordan | NR | 56.1% (653) | 1163 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 32.76% | 381 | 7 |

| Ning et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | 72.88% (446) | 612 | NR | Snowball | SAS | ≥50 | 16.34% | 100 | 7 |

| Prasad et al. (2020) | Nonphysician HCW | USA | NR | 90.8% (315) | 347 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 31.70% | 110 | 7 |

| Que et al. (2020) | HCW | China | 31.06 (6.99) | 69.06% (1578) | 2285 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 11.60% | 265 | 7 |

| Şahin et al. (2020) | HCW | Turkey | NR | 66.03% (620) | 939 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 18.96% | 178 | 7 |

| Salopek-Žiha et al. (2020) | HCW | Croatia | NR | NR | 124 | NR | Convenience | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 16.94% | 21 | 5 |

| Si et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | 70.68% (610) | 863 | 76.00% | Convenience | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 7.88% | 68 | 8 |

| Skoda et al. (2020) | HCW | Germany | NR | 75.99% (1690) | 2224 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 9.49% | 211 | 6 |

| Stojanov et al. (2020) | HCW | Serbia | 40.5 (8.37) | 66.17% (133) | 201 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 25.37% | 51 | 6 |

| Suryavanshi et al. (2020) | HCW | India | NR | 51.27% (101) | 197 | 20.40% | Snowball | GAD-7 | ≥9 | 28.43% | 56 | 6 |

| Temsah et al. (2020) | HCW | Saudi Arabia | NR | 75.09% (437) | 582 | 71.76% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 31.79% | 185 | 8 |

| Teng et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | NR | 338 | NR | Snowball | SAS | ≥50 | 13.31% | 45 | 6 |

| Teo et al. (2020) | Laboratory HCW | Singapore | 34 (NR) | 73.77% (90/122) | 103 | 84.43% | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 24.27% | 25 | 7 |

| Vanni et al. (2020) | HCW | Italy | 47 (10.37) | 65.22% (30) | 46 | 90.20% | Convenience | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 28.26% | 13 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (2020a) | HCW | China | NR | 85.84% (897) | 1045 | 73.18% | Convenience | HADS | >10 | 20.00% | 209 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (2020d) | HCW | China | 37 (NR) | 77.37% (212) | 274 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 13.87% | 38 | 6 |

| Wang et al. (2020c) | Pediatric HCW | China | 33.75 (8.41) | 90.24% (111) | 123 | 52.44% | Convenience | SAS | ≥50 | 7.32% | 9 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (2020b) | HCW | China | 33.5 (8.89) | 64.52% (1291) | 2001 | 72.06% | Convenience | HADS | >7 | 22.59% | 452 | 8 |

| Wańkowicz et al. (2020) | HCW | Poland | 40.25 (5.25) | 52.15% (230) | 441 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | >5 | 64.40% | 284 | 7 |

| Xiao et al. (2020) | HCW | China | NR | 67.22% (644) | 958 | NR | Convenience | HADS | >7 | 54.07% | 518 | 6 |

| Xiaoming et al. (2020) | HCW | China | 33.25 (8.26) | 77.93% (6874) | 8817 | 90.62% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 5.09% | 449 | 8 |

| Yang et al. (2020a) | Physical Therapists | South Korea | NR | 47.69% (31) | 65 | 89.04% | Convenience | GAD-7 | >5 | 32.31% | 21 | 7 |

| Yang et al. (2020b) | HCW | China | NR | NR | 449 | 91.08% | Convenience | SAS | ≥40 (raw) | 29.18% | 131 | 7 |

| Yáñez et al. (2020) | HCW | Peru | NR | 64.03% (194) | 303 | 75.75% | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 21.78% | 66 | 7 |

| Zhang et al. (2020a) | HCW | China | NR | 82.73% (1293) | 1563 | 80.32% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 12.92% | 202 | 8 |

| Zhang et al. (2020b) | HCW | Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru | 38.9 (10.1) | 67.98% (484) | 712 | 59.2% | Cluster | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 23.03% | 164 | 9 |

| Zhu et al. (2020b) | HCW | China | NR | 85.03% (4304) | 5062 | 77.07% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥8 | 24.06% | 1218 | 8 |

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). HCW = Healthcare workers; NR =not reported; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale; STAI-S = State-trait Anxiety Scale.

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). HCW = Healthcare workers; NR =not reported; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale; STAI-S = State-trait Anxiety Scale.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis based on samples of nurses.

| Author (Publication year) | Population | Country | Mean age (SD) | % Females (n) | Sample size (n) | Response rate (%) | Sampling method | Anxiety assessment | Diagnostic Criteria | Prevalence |

Quality assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | |||||||||||

| Dal’Bosco et al. (2020) | Nurses | Brazil | NR | 79% (89.8) | 88 | 18.49% | Convenience | HADS | >7 | 48.90% | 43 | 6 |

| Gupta et al. (2020b) | Nurses | India | NR | NR | 207 | 79.45% | Quota | HADS | >7 | 49.76% | 103 | 6 |

| Huang et al. (2020a) | Nurses | China | NR | NR | 160 | 93.50% | Cluster | SAS | ≥50 | 26.88% | 43 | 7 |

| Keubo et al. (2020) | Nurses | Cameroon | NR | NR | 168 | NR | Snowball | HADS | >10 | 44.64% | 75 | 5 |

| Lai et al. (2020) | Nurses | China | NR | 90.84% (694) | 764 | 68.69% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 12.70% | 97 | 8 |

| Li et al. (2020b) | Frontline Nurses | China | NR | 77.27% (136) | 176 | NR | Convenience | HAMA | ≥7 | 77.27% | 136 | 6 |

| Liu et al. (2020a) | Nurses | China | NR | NR | 1173 | NR | Convenience | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 12.87% | 151 | 6 |

| Ning et al. (2020) | Nurses | China | NR | 97.97% (289) | 295 | NR | Snowball | SAS | ≥50 | 20.34% | 60 | 6 |

| Pouralizadeh et al. (2020) | Nurses | Iran | 36.34 (8.74) | 95.2% (420) | 441 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 38.78% | 171 | 7 |

| Prasad et al. (2020) | Nurses | USA | NR | 93.1% (231) | 248 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 34.27% | 85 | 6 |

| Que et al. (2020) | Nurses | China | 35.94 (8.17) | 97.75% (195) | 208 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 14.90% | 31 | 6 |

| Şahin et al. (2020) | Nurses | Turkey | NR | NR | 254 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 21.65% | 55 | 5 |

| Skoda et al. (2020) | Nurses | Germany | NR | 86.83% (1511) | 1511 | NR | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 11.38% | 172 | 6 |

| Tu et al. (2020) | Frontline Nurses | China | 34.44 (5.85) | 100% (100) | 100 | 100% | Cluster | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 7.00% | 7 | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2020a) | Nurses | China | NR | NR | 773 | 73.18% | Convenience | HADS | >10 | 20.70% | 160 | 7 |

| Xiong et al. (2020a) | Nurses | China | NR | 97.31 (217) | 223 | 61.80% | Convenience | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 12.11% | 27 | 7 |

| Zhu et al. (2020a) | Frontline Nurses | China | NR | NR | 86 | NR | Convenience | SAS | ≥50 | 27.91% | 24 | 5 |

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). NR = not reported; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale.

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). NR = not reported; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis based on samples of medical doctors.

| Author (Publication year) | Population | Country | Mean age (SD) | % Females (n) | Sample size (n) | Response rate (%) | Sampling method | Anxiety assessment | Diagnostic Criteria | Prevalence |

Quality assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | |||||||||||

| Almater et al. (2020) | MD | Saudi Arabia | 32.9 (9.6) | 43.9% (47) | 107 | 30.60% | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 21.50% | 23 | 6 |

| Civantos et al. (2020) | MD | USA | NR | 39.26% (137) | 349 | NR | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 18.91% | 66 | 7 |

| Gupta et al. (2020b) | MD | India | NR | NR | 749 | 79.45% | Quota sampling | HADS | >7 | 35.25% | 264 | 7 |

| Huang et al. (2020a) | MD | China | NR | NR | 70 | 93.50% | Cluster Sampling | SAS | ≥50 | 14.29% | 10 | 7 |

| Keubo et al. (2020) | MD | Cameroon | NR | NR | 74 | NR | Snowball sampling | HADS | >10 | 36.49% | 27 | 5 |

| Lai et al. (2020) | MD | China | NR | 54.77% (270) | 493 | 68.69% | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 11.56% | 57 | 8 |

| Liu et al. (2020a) | MD | China | NR | NR | 858 | NR | Convenience sampling | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 11.31% | 97 | 6 |

| Ning et al. (2020) | MD | China | NR | 49.53% (157) | 317 | NR | Snowball sampling | SAS | ≥50 | 12.62% | 40 | 6 |

| Que et al. (2020) | MD | China | 33.69 (7.44) | 63.49% (546) | 860 | NR | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 11.98% | 103 | 7 |

| Şahin et al. (2020) | MD | Turkey | NR | NR | 580 | NR | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 18.62% | 108 | 6 |

| Skoda et al. (2020) | MD | Germany | NR | 65.65% (323) | 492 | NR | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 5.89% | 29 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (2020a) | MD | China | NR | NR | 149 | 73.18% | Convenience sampling | HADS | >10 | 20.13% | 30 | 6 |

| Zhu et al. (2020a) | Frontline MD | China | NR | 64.56% (51) | 79 | NR | Convenience sampling | SAS | ≥50 | 11.39% | 9 | 6 |

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). MD = Medical doctor; NR = not reported; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale.

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). MD = Medical doctor; NR = not reported; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis based on samples of frontline healthcare workers.

| Author (Publication year) | Population | Country | Mean age (SD) | % Females (n) | Sample size (n) | Response rate (%) | Sampling method | Anxiety assessment | Diagnostic Criteria | Prevalence |

Quality assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | |||||||||||

| Cai et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | China | 30.6 (8.8) | 68.82% (819) | 1173 | NR | Non-probabilistic sampling | BAI | ≥16 | 15.69% | 184 | 7 |

| Kannampallil et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | USA | NR | 51.38% (112) | 218 | 15.85% | NR | DASS-21 | ≥8 | 21.56% | 47 | 5 |

| Lai et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | China | NR | NR | 522 | 68.69% | Convenience sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 16.09% | 84 | 7 |

| Li et al. (2020b) | Frontline Nurses | China | NR | 77.27% (136) | 176 | NR | Convenience sampling | HAMA | ≥7 | 77.27% | 136 | 6 |

| Luceño-Moreno et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | Spain | 43.88 (10.82) | 86.40% (1228) | 1422 | 92.40% | Non probabilistic sampling | HADS | ≥7 | 79.32% | 1128 | 8 |

| Sandesh et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | Pakistan | NR | 42.86% (48) | 112 | NR | Convenience sampling | DASS-21 | ≥10 | 85.71% | 96 | 5 |

| Stojanov et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | Serbia | 39.1 (7.3) | 65.25% (77) | 118 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 31.36% | 37 | 6 |

| Tu et al. (2020) | Frontline Nurses | China | 34.44 (5.85) | 100% (100) | 100 | 100% | Cluster Sampling | GAD-7 | ≥10 | 7.00% | 7 | 8 |

| Wang et al. (2020a) | Frontline HCW | China | NR | NR | 401 | 73.18% | Convenience sampling | HADS | >10 | 24.69% | 99 | 7 |

| Wang et al. (2020b) | Frontline HCW | China | NR | 59.46% (393) | 661 | 72.06% | Convenience sampling | HADS | >7 | 28.74% | 190 | 8 |

| Wańkowicz et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | Poland | 40.47 (4.93) | 56.31% (116) | 206 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | >5 | 99.03% | 204 | 6 |

| Zhou et al. (2020) | Frontline HCW | China | 35.77 (8.13) | 81.19% (492) | 606 | NR | NR | GAD-7 | >5 | 45.38% | 275 | 7 |

| Zhu et al. (2020a) | Frontline HCW | China | 34.16 (8.06) | 83.03% (137) | 165 | NR | Convenience sampling | SAS | ≥50 | 20.00% | 33 | 6 |

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). HCW = healthcare workers; NR = not reported; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale.

Note. ⁎Quality score based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) standardized critical appraisal instrument for prevalence studies (Moola et al., 2017; see Table S2). HCW = healthcare workers; NR = not reported; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale.

The sample size of the studies ranged from 46 to 8817 participants. Only 30 studies reported the mean age of participants, which ranged from 29 to 47 years. All but two studies included men and women, with women outnumbering men in most of the studies that included this data (58/65). Fifty studies included general samples of HCWs, with 13 of these also including data on specific subgroups: nurses and doctors (7 studies), frontline HCWs (4 studies), and nurses, doctors and workers assisting COVID-19 patients (Frontline HCW). Four studies included samples of pediatric HCWs, with data specifically on nurses and doctors in only one of these. Five studies only included frontline HCW, with one providing data on subsamples of frontline nurses and doctors. Three studies focused only on nurses, and another two on frontline nurses, while two studies only included doctors. The remaining 5 studies focused on professional groups considered to be HCW: dental workers, laboratory HCW, physiotherapists, and non-physician HCW (with a subpopulation of nurses). A total of 33 studies were conducted in China, 5 studies in Italy, 4 studies were from Turkey, 3 studies from each of India and USA, 2 studies from Ecuador, Peru, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, and a single study from each of Bolivia, Brazil, Cameroon, Croatia, Germany, Iran, Jordan, Kosovo, Libya, Nepal, Oman, Pakistan, Poland, Serbia, South Korea and Thailand. All studies were performed using online questionnaires, and of those that reported sampling methodology, all but four used non-random approaches. The response rate was reported by 38 studies and ranged from 18.5% to 100%. All studies measured anxiety by means of standardized scales, most commonly the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD, 35 studies), the Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS, 10 studies), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS, 10 studies), and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS, 9 studies).

3.3. Quality assessment

The risk of bias scores ranged from 5 to 9, with a mean score of 7.01 (Table S2). The most common sources of bias were: (a) recruitment of inappropriate participants (67 studies), (b) response rate not reported or large number of non-responders (39 studies), and (c) sample size too small to ensure good precision of the final estimate (24 studies).

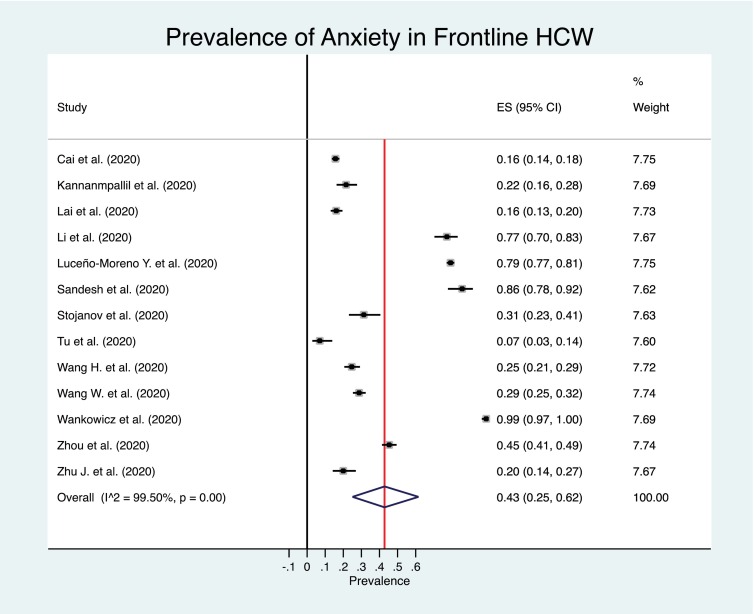

3.4. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety

The estimated overall prevalence of anxiety was 25% in overall samples of HCW (95% CI: 21%–29%) (Fig. 2 ), 27% in nurses (95% CI: 20%–34%) (Fig. 3 ), 17% in medical doctors (95% CI: 12%–22%) (Fig. 4 ), and 43% in Frontline HCW (95% CI: 25%–62%) (Fig. 5 ), with significant heterogeneity between studies (Q test: p < 0.001) in HCW overall, nurses, doctors and frontline HCW.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the prevalence of anxiety among healthcare workers

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the prevalence of anxiety among nurses.

Figure 4.

Forest plot for the prevalence of anxiety among medical doctors.

Figure 5.

Forest plot for the prevalence of anxiety among frontline healthcare workers.

3.5. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis

Potential sources of heterogeneity were investigated across the studies. Our subgroup analysis showed that the prevalence of anxiety was lower for studies using the DASS-21, a convenience sampling method, with high methodological quality, or studies conducted in China (Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Overall prevalence rates of anxiety according to study characteristics.

| Healthcare Workers (HCW) |

Nurses |

Medical Doctors |

Frontline HCW |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | p⁎ | No. of studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | p⁎ | No. of studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | p⁎ | No. of studies | Prevalence (%) (95% CI) | p⁎ | |

| Anxiety assessment | 0.179 | 0.919 | 0.502 | 0.711 | ||||||||

| GAD-7 | 29 | 23 (18–28) | 8 | 18 (11–26) | 7 | 16 (11–22) | 5 | 41 (11–76) | ||||

| HADS | 8 | 40 (30–51) | 4 | 40 (23-59) | 2 | 33 (30–36) | 3 | 44 (10–82) | ||||

| DASS-21 | 8 | 18 (12–26) | 1 | 13 (11–15) | 1 | 11 (9–14) | 2 | 43 (38–49) | ||||

| SAS | 9 | 17 (13–22) | 3 | 24 (19–29) | 3 | 13 (10–16) | 1 | 20 (14–27) | ||||

| STAI | 2 | 71 (67–75) | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Other (BAI/HAMA/GADS/STAI) | 3 | 23 (21–25) | 1 | 77 (70–83) | - | - | - | 2 | 22 (20–25) | |||

| Country | 0.005 | 0.190 | 0.077 | 0.051 | ||||||||

| China | 26 | 19 (14–24) | 10 | 22 (14–31) | 7 | 12 (11–14) | 8 | 28 (17–40) | ||||

| Other | 33 | 30 (25–36) | 7 | 35 (21–55) | 6 | 21 (12–33) | 5 | 68 (37–92) | ||||

| Sampling method | 0.857 | 0.640 | 0.070 | 0.747 | ||||||||

| Convenience | 36 | 24 (19–29) | 11 | 25 (17–34) | 9 | 14 (11–17) | 6 | 42 (23–62) | ||||

| Other | 14 | 26 (19–33) | 6 | 30 (19–43) | 4 | 24 (11–39) | 3 | 31 (0–83) | ||||

| Quality rating | 0.632 | 0.168 | 0.721 | 0.164 | ||||||||

| Medium (<7) | 13 | 27 (16–38) | 11 | 32 (21–44) | 7 | 18 (13–23) | 5 | 67 (30–95) | ||||

| High (≥ 7) | 46 | 25 (21–29) | 6 | 19 (11–28) | 6 | 15 (8–25) | 7 | 30 (11–53) | ||||

Note: 95%CI = 95% Confidence interval; HCW = healthcare workers; NR = not reported; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; DASS-21 = Depression, Anxiety and Stress scales; GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HAMA = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; SAS = Zung Self-Rating Scale; STAI = State-trait Anxiety Scale.

P value obtained from univariate meta-regression.

3.6. Sensitive analysis

Excluding each study one-by-one from the analysis did not substantially change the pooled prevalence of anxiety. This indicated that no single study had a disproportional impact on the overall prevalence (data not shown).

3.7. Risk of publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot (Fig. 6 ) suggested a small publication bias for the estimation of the pooled prevalence in HCW, nurses and medical doctors, confirmed by significant Egger’s test results (p < 0.05). In contrast, no publication bias was identified in the estimation of the pooled prevalence in frontline HCW (Egger’s test: p = 0.804)

Figure 6.

Funnel plot for the prevalence of anxiety.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of main findings

The COVID-19 pandemic is having an unprecedented impact on HCW, with anxiety being one of most commonly reported mental condition. The present study provides an up-to-date meta-analysis of studies reporting the prevalence of anxiety in HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our meta-analysis is based on 71 studies, and to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to report overall prevalence rates of anxiety in different occupational categories of HCW (i.e., nurses, medical doctors and frontline HCW). Our findings show that HCW, nurses and doctors report high anxiety levels (25%, 27% and 17%, respectively), and up to 43% of the frontline HCW display high levels of anxiety symptoms. The prevalence found in HCW is similar to the one reported by Pappa et al. (23.2%) (Pappa et al., 2020) but lower than the one reported by Luo et al. (33%) (Luo et al., 2020). These discrepancies might be explained in light of the different number of studies included or the origin of the samples (i.e., China).

Some previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted to report the prevalence of anxiety in the general population. A recent meta-analysis conducted from December 2019 to August 2020 and based on 43 population-based studies reported an overall prevalence of anxiety of 25% (Santabárbara et al., 2021). Similarly, a recent systematic review (Xiong et al., 2020a) found that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms ranged from 6.3% to 50.9% in the general population during the COVID-19 outbreak (based on 11 population-based studies). The present study reports similar prevalence rates of anxiety in HCW to that reported in the general population, although the proportion of anxiety in frontline HCW appears to be higher (43%).

The finding of frontline HCW as the workers with the highest levels of anxiety is consistent with previous literature (Alshekaili et al., 2020; Buselli et al., 2020; Cabarkapa et al., 2020). Frontline HCW are directly responsible for caring for patients with COVID-19, and are exposed to several risk factors for anxiety such as burnout, lack of treatment guidelines, and feeling inadequately supported (Lai et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020). The exposure to critical medical situation and death and trauma make frontline HCW especially vulnerable to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Carmassi et al., 2020). Despite the fact that the present meta-analysis is based on studies that evaluated anxiety symptoms with standardized questionnaire, they correspond to overall anxiety, but do not specifically assess the presence of PSTD. However, symptoms of PSTD might be also indirectly captured by these instruments.

The relatively high anxiety levels observed in nurses (27%) is also consistent with some previous reports showing that nurses are particularly affected by severe emotional distress (Dennison Himmelfarb and Baptiste, 2020). Nurses have direct contact with patients and therefore have more direct emotional contact. Recent systematic reviews have shown that being a nurse in the COVID-19 pandemic is a risk factor for anxiety (Cabarkapa et al., 2020; Sanghera et al., 2020). Factors promoting anxiety include fear of being infected or infecting others (Mo et al., 2020), lack of personal protective equipment, lack of access to COVID-19 testing, and lack of accurate information about the disease (Shanafelt et al., 2020).

4.2. Strengths and limitations

Some strengths of our meta-analysis are the inclusion of a large body of literature and the use of a rigorous approach to identify publication bias (i.e., Egger’s test). These results show that there is a small bias in the estimation of the pooled prevalence of anxiety for HCW, nurses and medical doctors but null for frontline HCW.

However, some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, the majority of the studies included were based on cross-sectional data and non-probabilistic samples. The epidemiological status of COVID-19 is constantly changing worldwide, and thus longitudinal studies are necessary to determine whether the elevated levels anxiety are sustained, reduced or increased over time (Pierce et al., 2020). Second, the studies used a variety of self-report anxiety scales, and the use of some tests was associated with significantly higher prevalence of anxiety than others. Ideally, studies should use the same measure of anxiety, and if possible, include a diagnosis based on clinical interviews. However, this is not always possible, and the use of brief, self-reported standardized questionnaires appears as a common practice in epidemiological studies. Finally, while we were able to include studies from many countries, the majority of studies were focused on Asian countries, particularly on Chinese samples. Europe and America are both highly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, thus there is still need for epidemiological studies in these regions using randomized sampling design, when possible.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis confirms the huge mental toll of the COVID-19 pandemic in HCW, especially in frontline HCW and nurses. Therefore, there is an urgent need to prevent and treat common mental health problems in this population. Several strategies have been recommended to support the mental health and well-being of HCW. These include accurate work-related information, regular breaks, adequate rest and sleep, a healthy diet, physical activity, peer support, family support, avoidance of unnecessary coping strategies, limiting the use of social media and professional counselling or psychological services (Pollock et al., 2020). In addition, psychological support based on coping strategies should be provided to control anxiety. Spiritual care programs and other approaches developed for end-of-life and palliative care could also be helpful (Chirico et al., 2020).

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychological support for health workers has been implemented in different countries. In China, different groups of mental health providers used social networking platforms and telephone aids to implement mental health support by offering guidance and supervision to solve psychological problems (Chen et al., 2020a; Cheng et al., 2020a). In Iran, consistent measures were taken to prevent, screen and treat mental health disorders among staff serving patients with COVID-19 (Zandifar et al., 2020). In the UK, in the first three weeks of the outbreak, a digital learning package was developed and evaluated. This e-learning package included evidence-based guidance, support and signage related to psychological well-being for all health care workers in the UK (Blake et al., 2020). In Spain, the Ministry of Health and the General Council of Psychologists activated a telephone support line for professionals with direct intervention in the management of the pandemic, such as health frontline care workers (Spanish Government, 2020). Finally, it is worth to mention the use of interventions based on cognitive behavior therapy to mitigate maladaptive coping strategies and change cognitive bias (Ho et al., 2020). These interventions can be delivered through e-health platforms (such as the Internet) and have been widely proved to be cost-effective for treating anxiety disorders (Zhang and Ho, 2017).

These are only examples of the psychological support being given in different countries. We advocate that the psychological support provided should be adapted to specific groups of workers and that further research should be carried out into which measures are most effective in minimizing the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in HCW.

Ethical statement for solid state ionics

Hereby, I Beatriz Olaya consciously assure that for the manuscript “Prevalence of anxiety in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review with meta-analysis” the following is fulfilled:

-

1)

This material is the authors' own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere.

-

2)

The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

-

3)

The paper reflects the authors' own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner.

-

4)

The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers.

-

5)

The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research.

-

6)

All sources used are properly disclosed (correct citation). Literally copying of text must be indicated as such by using quotation marks and giving proper reference.

-

7)

All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper, and will take public responsibility for its content.

The violation of the Ethical Statement rules may result in severe consequences.

To verify originality, your article may be checked by the originality detection software iThenticate. See also http://www.elsevier.com/editors/plagdetect.

I agree with the above statements and declare that this submission follows the policies of Solid State Ionics as outlined in the Guide for Authors and in the Ethical Statement.

Funding

This work has been supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Madrid, Spain [grants 94/1562, 97/1321E, 98/0103, 01/0255, 03/0815, 06/0617, G03/128 and 19/01874]. BO’s work is supported by the PERIS program 2016-2020 “Ajuts per a la Incorporació de Científics i Tecnòlegs” [grant number SLT006/17/00066], with the support of the Health Department from the Generalitat de Catalunya, and by the Miguel Servet programme (reference CP20/00040), funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III and co-funded by European Union (ERDF/ESF, "Investing in your future"). Sponsors had no involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110244.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Table S1. PRISMA checklist.

Table S2. Quality assessment with the JBI appraisal checklist for prevalence studies.

References

- Li G., Miao J., Wang H., Xu S., Sun W., Fan Y., Zhang C., Zhu S., Zhu Z., Wang W. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Department of Neurology, Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China. Nursing Department, Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology; Wuhan: 2020. Psychological impact on women health workers involved in COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan: a cross-sectional study; pp. 895–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temsah M.-H., Al-Sohime F., Alamro N., Al-Eyadhy A., Al-Hasan K., Jamal A., Al-Maglouth I., Aljamaan F., Al Amri M., Barry M., Al-Subaie S., Somilyj A.M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.021. http://iacs.c17.net/openurl?sid=EMBASE&issn=1876035X&id=doi:10.1016%2Fj.jiph.2020.05.021&atitle=The+psychological+impact+of+COVID-19+pandemic+on+health+care+workers+in+a+MERS-CoV+endemic+country&stitle=J.+Infect.+Public+Health&title=Journal+of+Infection+and+Public+Health&volume=&issue=&spage=&epage=&aulast=Temsah&aufirst=Mohamad-Hani&auinit=M.-H.&aufull=Temsah+M.-H.&coden=&isbn=&pages=-&date=2020&auinit1=M&auinitm=-H LK- [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almater A., Tobaigy M., Younis A., Alaqeel M., Abouammoh M. Effect of 2019 coronavirus pandemic on ophthalmologists practicing in Saudi Arabia: a psychological health assessment. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2020;27:79–85. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_220_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshekaili M., Hassan W., Al Said N., Al Sulaimani F., Jayapal S.K., Al-Mawali A., Chan M.F., Mahadevan S., Al-Adawi S. Factors associated with mental health outcomes across healthcare settings in Oman during COVID-19: frontline versus non-frontline healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apisarnthanarak A., Apisarnthanarak P., Siripraparat C., Saengaram P., Leeprechanon N., Weber D.J. Impact of anxiety and fear for COVID-19 toward infection control practices among Thai healthcare workers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayhan Başer D., Çevik M., Gümüştakim Ş., Başara E. Assessment of individuals’ attitude, knowledge and anxiety toward Covid 19 at the first period of the outbreak in Turkey: a web based cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babore A., Lombardi L., Viceconti M.L., Pignataro S., Marino V., Crudele M., Candelori C., Bramanti S.M., Trumello C. Psychological effects of the COVID-2019 pandemic: perceived stress and coping strategies among healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113366. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badahdah A., Khamis F., Al Mahyijari N., Al Balushi M., Al Hatmi H., Al Salmi I., Albulushi Z., Al Noomani J. The mental health of health care workers in Oman during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020939596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake H., Bermingham F., Johnson G., Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buselli R., Corsi M., Baldanzi S., Chiumiento M., Del Lupo E., Dell’Oste V., Bertelloni C.A., Massimetti G., Dell’Osso L., Cristaudo A., Carmassi C. Professional quality of life and mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Sars-Cov-2 (Covid-19) Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:6180. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabarkapa S., Nadjidai S.E., Murgier J., Ng C.H. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: a rapid systematic review. Brain, Behav. Immun. Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q., Feng H., Huang J., Wang M., Wang Q., Lu X., Xie Y., Wang X., Liu Z., Hou B., Ouyang K., Pan J., Li Q., Fu B., Deng Y., Liu Y. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: a case-control study. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmassi C., Foghi C., Dell’Oste V., Cordone A., Bertelloni C.A., Bui E., Dell’Osso L. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., Guo J., Fei D., Wang L., He L., Sheng C., Cai Y., Li X., Wang J., Zhang Z. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Liu X., Wang D., Jin Y., He M., Ma Y., Zhao X., Song S., Zhang L., Xiang X., Yang L., Song J., Bai T., Hou X. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01954-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhang S.X., Jahanshahi A.A., Alvarez-Risco A., Dai H., Li J., Ibarra V.G. Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Heal. Surveill. 2020;6 doi: 10.2196/20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhou H., Zhou Y., Zhou F. Prevalence of self-reported depression and anxiety among pediatric medical staff members during the COVID-19 outbreak in Guiyang, China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.O.S., Li Ping Wah-Pun Sin E. The effects of nonconventional palliative and end-of-life care during COVID-19 pandemic on mental health—Junior doctors’ perspective. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2020;12:S146–S147. doi: 10.1037/tra0000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P., Xia G., Pang P., Wu B., Jiang W., Li Y.-T., Wang M., Ling Q., Chang X., Wang J., Dai X., Lin X., Bi X. COVID-19 epidemic peer support and crisis intervention via social media. Community Ment. Health J. 2020;56:786–792. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00624-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F.-F., Zhan S.-H., Xie A.-W., Cai S.-Z., Hui L., Kong X.-X., Tian J.-M., Yan W.-H. Anxiety in Chinese pediatric medical staff during the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019: a cross-sectional study. Transl. Pediatr. 2020;9:231–236. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.04.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M.W.L., Ho R.C.M., Lim Y., Mak A. Conducting a meta-analysis: basics and good practices. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2012;15:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q., Jing M., Goh Y., Ngiam N.J.H., Yeo L.L.L., Ahmad A., Ahmed Khan F., Napolean Shanmugam G., Sharma A.K., Komalkumar R.N., Meenakshi P.V., Shah K., Patel B., Chan B.P.L., Sunny S., Chandra B., Ong J.J.Y., Paliwal P.R., Wong L.Y.H., Sagayanathan R., Chen J.T., Ying Ng A.Y., Teoh H.L., Tsivgoulis G., Ho C.S., Ho R.C., Sharma V.K. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F., Nucera G., Magnavita N. Protecting the mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency. BJPsych Int. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1192/bji.2020.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Civantos A.M., Byrnes Y., Chang C., Prasad A., Chorath K., Poonia S.K., Jenks C.M., Bur A.M., Thakkar P., Graboyes E.M., Seth R., Trosman S., Wong A., Laitman B.M., Harris B.N., Shah J., Stubbs V., Choby G., Long Q., Rassekh C.H., Thaler E., Rajasekaran K. Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: National study. Head Neck. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hed.26292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolo U., Bellini P., Bencivenni D., Iani C., Checchi V. Epidemiological aspects and psychological reactions to COVID-19 of dental practitioners in the Northern Italy districts of modena and reggio emilia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna; Austria: 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Dal’Bosco E.B., Messias Floriano L.S., Skupien S.V., Arcaro G., Martins A.R., Correa Anselmo A.C. Mental health of nursing in coping with COVID-19 at a regional university hospital. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020;73 doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison Himmelfarb C.R., Baptiste D. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020;35:318–321. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tella M., Romeo A., Benfante A., Castelli L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J. Eval. Clin. Pr. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jep.13444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosil Santamaría M., Ozamiz-Etxebarria N., Redondo Rodríguez I., Jaureguizar Alboniga-Mayor J., Picaza Gorrotxategi M. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on a sample of Spanish health professionals. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Schneider M., Davey Smith G. Spurious precision? Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 1998;316:140–144. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbay R.Y., Kurtulmuş A., Arpacıoğlu S., Karadere E. Depression, anxiety, stress levels of physicians and associated factors in Covid-19 pandemics. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113130. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadi M., Msherghi A., Elgzairi M., Alhashimi A., Bouhuwaish A., Biala M., Abuelmeda S., Khel S., Khaled A., Alsoufi A., Elmabrouk A., Alshiteewi F. Bin, Alhadi B., Alhaddad S., Gaffaz R., Elmabrouk O., Hamed T. Ben, Alameen H., Zaid A., Elhadi A., Albakoush A. Psychological status of healthcare workers during the civil war and COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;137:110221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallopeni F., Bajraktari I., Selmani E., Tahirbegolli I.A., Sahiti G., Muastafa A., Bojaj G., Muharremi V.B., Tahirbegolli B. Anxiety and depressive symptoms among healthcare professionals during the Covid-19 pandemic in Kosovo: A cross sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;137:110212. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Iglesias J.J., Gomez-Salgado J., Martin-Pereira J., Fagundo-Rivera J., Ayuso-Murillo D., Martinez-Riera J.R., Ruiz-Frutos C., García-Iglesias J.J., Gómez-Salgado J., Martín-Pereira J., Fagundo-Rivera J., Ayuso-Murillo D., Martínez-Riera J.R., Ruiz-Frutos C. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Rev. Esp. Salud. Publica. 2020;94 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti E.M., Pedroli E., D’Aniello G.E., Stramba Badiale C., Pietrabissa G., Manna C., Stramba Badiale M., Riva G., Castelnuovo G., Molinari E., Badiale C.S., Pietrabissa G., Manna C., Badiale M.S., Riva G., Castelnuovo G., Molinari E. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A.K., Mehra A., Niraula A., Kafle K., Deo S.P., Singh B., Sahoo S., Grover S. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among the healthcare workers in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Prasad A.S., Dixit P.K., Padmakumari P., Gupta S., Abhisheka K. Survey of prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among 1124 healthcare workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic across India. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel P.T. The heterogeneity statistic I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.S., Chee C.Y., Ho R.C. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2020;49:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.Z., Han M.F., Luo T.D., Ren A.K., Zhou X.P. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Chinese J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2020;38:192–195. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121094-20200219-00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Wang Y., Liu J., Ye P., Chen X., Xu H., Qu H., Ning G. Factors influencing anxiety of health care workers in the radiology department with high exposure risk to COVID-19. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/msm.926008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J.P., Saratzis A., Sutton A.J., Boucher R.H., Sayers R.D., Bown M.J. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;67:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huremović D. In: Psychiatry of Pandemics, A Mental Health Response to Infection Outbreak. Huremović D., editor. Springer Nature, Switzerland AG; Basel, Switzerland: 2019. Mental health of quarantine and isolation; pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kannampallil T.G., Goss C.W., Evanoff B.A., Strickland J.R., McAlister R.P., Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keubo F.R.N., Mboua P.C., Tadongfack T.D., Tchoffo E.F., Tatang C.T., Zeuna J.I., Noupoue E.M., Tsoplifack C.B., Folefack G.O. Psychological distress among health care professionals of the three COVID-19 most affected Regions in Cameroon: prevalence and associated factors. Ann. Med. Psychol. (Paris). 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koksal E., Dost B., Terzi Ö., Ustun Y.B., Özdin S., Bilgin S. Evaluation of depression and anxiety levels and related factors among operating theater workers during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., Wu J., Du H., Chen T., Li R., Tan H., Kang L., Yao L., Huang M., Wang H., Wang G., Liu Z., Hu S. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Chen Y., Lv J., Liu L., Zong S., Li H. Anxiety and related factors in frontline clinical nurses fighting COVID-19 in Wuhan. Med. 2020;99 doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000021413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Wu K., Zhou Y., Huang X., Zhou Y., Liu Z. Mental health in frontline medical workers during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease epidemic in China: a comparison with the general population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K., Yang B.X., Luo D., Liu Q., Ma S., Huang R., Lu W., Majeed A., Lee Y., Lui L.M.W., Mansur R.B., Nasri F., Subramaniapillai M., Rosenblat J.D., Liu Z., McIntyre R.S. The mental health effects of COVID-19 on health care providers in China. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2020;177:635–636. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20040374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang L., Chen L., Zhang X., Bao L., Shi Y. Mental health status of paediatric medical workers in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.-Y., Yang Y.-Z., Zhang X.-M., Xu X., Dou Q.-L., Zhang W.-W., Cheng A.S.K. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020;148 doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W., Wang H., Lin Y., Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luceño-Moreno L., Talavera-Velasco B., García-Albuerne Y., Martín-García J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita N., Tripepi G., Di Prinzio R.R. Symptoms in health care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic. a cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendran K., Patel S., Sproat C. Psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff in a dental teaching hospital. Br. Dent. J. 2020;229:127–132. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1792-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y., Deng L., Zhang L., Lang Q., Liao C., Wang N., Qin M., Huang H. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020;28:1002–1009. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Altman D., Antes G., Atkins D., Barbour V., Barrowman N., Berlin J.A., Clark J., Clarke M., Cook D., D’Amico R., Deeks J.J., Devereaux P.J., Dickersin K., Egger M., Ernst E., Gøtzsche P.C., Grimshaw J., Guyatt G., Higgins J., Ioannidis J.P.A., Kleijnen J., Lang T., Magrini N., McNamee D., Moja L., Mulrow C., Napoli M., Oxman A., Pham B., Rennie D., Sampson M., Schulz K.F., Shekelle P.G., Tovey D., Tugwell P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moola S., Munn Z., Tufanaru C., Aromataris E., Sears K., Sfetc R., Currie M., Lisy K., Qureshi R., Mattis P., Mu P.-F. In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk; pp. 219–226. [Google Scholar]

- Naser A.Y., Dahmash E.Z., Al-Rousan R., Alwafi H., Alrawashdeh H.M., Ghoul I., Abidine A., Bokhary M.A., Al-Hadithi H.T., Ali D., Abuthawabeh R., Abdelwahab G.M., Alhartani Y.J., Al Muhaisen H., Dagash A., Alyami H.S. Mental health status of the general population, healthcare professionals, and university students during 2019 coronavirus disease outbreak in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav. 2020;10 doi: 10.1002/brb3.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X., Yu F., Huang Q., Li X., Luo Y., Huang Q., Chen C. The mental health of neurological doctors and nurses in Hunan Province, China during the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:436. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02838-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce M., McManus S., Jessop C., John A., Hotopf M., Ford T., Hatch S., Wessely S., Abel K.M. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:567–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A., Campbell P., Cheyne J., Cowie J., Davis B., McCallum J., McGill K., Elders A., Hagen S., McClurg D., Torrens C., Maxwell M. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouralizadeh M., Bostani Z., Maroufizadeh S., Ghanbari A., Khoshbakht M., Alavi S.A., Ashrafi S. Anxiety and depression and the related factors in nurses of Guilan University of Medical Sciences hospitals during COVID-19: A web-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2020;13:100233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A., Civantos A.M., Byrnes Y., Chorath K., Poonia S., Chang C., Graboyes E.M., Bur A.M., Thakkar P., Deng J., Seth R., Trosman S., Wong A., Laitman B.M., Shah J., Stubbs V., Long Q., Choby G., Rassekh C.H., Thaler E.R., Rajasekaran K. Snapshot impact of COVID-19 on mental wellness in nonphysician otolaryngology health care workers: a national study. OTO open. 2020;4 doi: 10.1177/2473974X20948835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que J., Shi L., Deng J., Liu J., Zhang L., Wu S., Gong Y., Huang W., Yuan K., Yan W., Sun Y., Ran M., Bao Y., Lu L. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen. Psychiatry. 2020;33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şahin M.K., Aker S., Şahin G., Karabekiroğlu A. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress and insomnia and related factors in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. J. Community Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00921-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salopek-Žiha D., Hlavati M., Gvozdanović Z., Gašić M., Placento H., Jakić H., Klapan D., Šimić H. Differences in distress and coping with the COVID-19 stressor in nurses and physicians. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020;32:287–293. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2020.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandesh R., Shahid W., Dev K., Mandhan N., Shankar P., Shaikh A., Rizwan A. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare professionals in Pakistan. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.8974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghera J., Pattani N., Hashmi Y., Varley K.F., Cheruvu M.S., Bradley A., Burke J.R. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting—a systematic review. J. Occup. Health. 2020;62 doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santabárbara J., Lasheras I., Lipnicki D.M., Bueno-Notivol J., Pérez-Moreno M., López-Antón R., De la Cámara C., Lobo A., Gracia-García P. Prevalence of anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic: an updated meta-analysis of community-based studies. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021;109:110207. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si M.Y., Su X.Y., Jiang Y., Wang W.J., Gu X.F., Ma L., Li J., Zhang S.K., Ren Z.F., Ren R., Liu Y.L., Qiao Y.L. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2020;9:113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva F.C.T., Neto M.L.R. Psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoda E.M., Teufel M., Stang A., Jöckel K.H., Junne F., Weismüller B., Hetkamp M., Musche V., Kohler H., Dörrie N., Schweda A., Bäuerle A. Psychological burden of healthcare professionals in Germany during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: differences and similarities in the international context. J. Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Government . 2020. El Ministerio de Sanidad y el Consejo General de Psicólogos activan un teléfono de apoyo para la población afectada por la COVID-19 [WWW Document] [Google Scholar]

- Stojanov J., Malobabic M., Stanojevic G., Stevic M., Milosevic V., Stojanov A. Quality of sleep and health-related quality of life among health care professionals treating patients with coronavirus disease-19. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020942800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryavanshi N., Kadam A., Dhumal G., Nimkar S., Mave V., Gupta A., Cox S.R., Gupte N. Mental health and quality of life among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Brain Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1002/brb3.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Z., Huang J., Qiu Y., Tan Y., Zhong Q., Tang H., Wu H., Wu Y., Chen J. Mental health of front-line staff in prevention of coronavirus disease 2019. J. Cent. South Univ. Med. Sci. 2020;45:613–619. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2020.200241. 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2020.200241 (Zhong nan da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo W.Z.Y., Soo Y.E., Yip C., Lizhen O., Chun-Tsu L. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on “hidden” frontline healthcare workers. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020950772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S.G., Higgins J.P.T. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat. Med. 2002;21:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z.H., He J.W., Zhou N. Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2020;99 doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000020769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanni G., Materazzo M., Santori F., Pellicciaro M., Costesta M., Orsaria P., Cattadori F., Pistolese C.A., Perretta T., Chiocchi M., Meucci R., Lamacchia F., Assogna M., Caspi J., Granai A.V., Majo D.E., Chiaravalloti A., D’Angelillo M.R., Barbarino R., Ingallinella S., Morando L., Dalli S., Portarena I., Altomare V., Tazzioli G., Buonomo O.C. The effect of coronavirus (COVID-19) on breast cancer teamwork: a multicentric survey. In Vivo. 2020;34:1685–1694. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E., Pérez V., Arango C. Psychiatry in the aftermath of COVID-19. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2020;13:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Huang D., Huang H., Zhang J., Guo L., Liu Y., Ma H., Geng Q. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in Guangdong, China: a cross-sectional study. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1017/s0033291720002561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Song W., Xia Z., He Y., Tang L., Hou J., Lei S. Sleep disturbance and psychological profiles of medical staff and non-medical staff during the early outbreak of COVID-19 in Hubei Province, China. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Xie L., Xu Y., Yu S., Yao B., Xiang D. Sleep disturbances among medical workers during the outbreak of COVID-2019. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 2020 doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.Q., Zhang M., Liu G.M., Nan S.Y., Li T., Xu L., Xue Y., Wang L., Qu Y.D., Liu F. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease (2019) (COVID-19) epidemic on medical staff in different posts in China: A multicenter study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;129:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wańkowicz P., Szylińska A., Rotter I. Assessment of mental health factors among health professionals depending on their contact with COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Zhu X., Fu S., Hu Y., Li X., Xiao J. Psychological impact of healthcare workers in China during COVID-19 pneumonia epidemic: a multi-center cross-sectional survey investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;274:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoming X., Ming A., Su H., Wo W., Jianmei C., Qi Z., Hua H., Xuemei L., Lixia W., Jun C., Lei S., Zhen L., Lian D., Jing L., Handan Y., Haitang Q., Xiaoting H., Xiaorong C., Ran C., Qinghua L., Xinyu Z., Jian T., Jing T., Guanghua J., Zhiqin H., Nkundimana B., Li K. The psychological status of 8817 hospital workers during COVID-19 Epidemic: a cross-sectional study in Chongqing. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;276:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., McIntyre R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Yi S., Lin Y. The psychological status and self-efficacy of nurses during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Inquiry. 2020;57 doi: 10.1177/0046958020957114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]