Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic is having profound mental health consequences for many people. Concerns have been expressed that, at their most extreme, these consequences could manifest as increased suicide rates. We aimed to assess the early effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates around the world.

Methods

We sourced real-time suicide data from countries or areas within countries through a systematic internet search and recourse to our networks and the published literature. Between Sept 1 and Nov 1, 2020, we searched the official websites of these countries’ ministries of health, police agencies, and government-run statistics agencies or equivalents, using the translated search terms “suicide” and “cause of death”, before broadening the search in an attempt to identify data through other public sources. Data were included from a given country or area if they came from an official government source and were available at a monthly level from at least Jan 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020. Our internet searches were restricted to countries with more than 3 million residents for pragmatic reasons, but we relaxed this rule for countries identified through the literature and our networks. Areas within countries could also be included with populations of less than 3 million. We used an interrupted time-series analysis to model the trend in monthly suicides before COVID-19 (from at least Jan 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020) in each country or area within a country, comparing the expected number of suicides derived from the model with the observed number of suicides in the early months of the pandemic (from April 1 to July 31, 2020, in the primary analysis).

Findings

We sourced data from 21 countries (16 high-income and five upper-middle-income countries), including whole-country data in ten countries and data for various areas in 11 countries). Rate ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs based on the observed versus expected numbers of suicides showed no evidence of a significant increase in risk of suicide since the pandemic began in any country or area. There was statistical evidence of a decrease in suicide compared with the expected number in 12 countries or areas: New South Wales, Australia (RR 0·81 [95% CI 0·72–0·91]); Alberta, Canada (0·80 [0·68–0·93]); British Columbia, Canada (0·76 [0·66–0·87]); Chile (0·85 [0·78–0·94]); Leipzig, Germany (0·49 [0·32–0·74]); Japan (0·94 [0·91–0·96]); New Zealand (0·79 [0·68–0·91]); South Korea (0·94 [0·92–0·97]); California, USA (0·90 [0·85–0·95]); Illinois (Cook County), USA (0·79 [0·67–0·93]); Texas (four counties), USA (0·82 [0·68–0·98]); and Ecuador (0·74 [0·67–0·82]).

Interpretation

This is the first study to examine suicides occurring in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in multiple countries. In high-income and upper-middle-income countries, suicide numbers have remained largely unchanged or declined in the early months of the pandemic compared with the expected levels based on the pre-pandemic period. We need to remain vigilant and be poised to respond if the situation changes as the longer-term mental health and economic effects of the pandemic unfold.

Funding

None.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound mental health consequences1 and there are concerns that it could lead to increases in suicide rates.2 However, few studies have examined the effects of previous widespread disease outbreaks on suicide. Two systematic reviews collectively identified ten studies, focusing on epidemics or pandemics of influenza (1889–93 [UK]; 1918–19 [USA]; 2009–13 [USA]), severe acute respiratory syndrome (2003 [Hong Kong and Taiwan]), and Ebola virus (2013–16 [Guinea]).3, 4 These reviews suggested that, although suicide rates might sometimes increase following these sorts of public health emergencies, the changes might not necessarily occur immediately, and that the risk might actually be reduced initially.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Evidence on the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and suicide before this study predominantly came from studies that relied on unofficial data sources or did not account for pre-existing trends. We have been conducting a living systematic review since the onset of the pandemic, searching the literature (including preprints) on a daily basis via PubMed, Scopus, medRxiv, bioRxiv, the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset by Semantic Scholar and the Allen Institute for AI, and the WHO COVID-19 database. We used over 20 search terms for suicide (eg, “suicid*”), suicidal behaviour (eg, “attempted suicide”), and self-harm (eg, “self-harm*”), in combination with a range of terms for COVID-19 (eg, “coronavirus” OR “COVID*” or “SARS-CoV-2”). Databases were searched from Jan 1, 2020, with no language restrictions. As of Dec 8, 2020, we had identified 21 reports but only five of these accounted for temporal trends in suicides (eg, by using time-series analyses). Three of these studies found no change in suicide numbers in Greece, Queensland (Australia), and Massachusetts (USA), and the fourth identified a decrease in Peru. The fifth highlighted a decrease followed by an increase in Japan, which appeared to be related to pandemic-induced employment shocks.

Added value of this study

This study drew on data from 21 countries and used an analytical approach that controlled for pre-existing trends to assess whether patterns of suicide have changed since the COVID-19 pandemic was declared. It is the first study to explore the potential suicide-related effects of COVID-19 at this scale. The results of the primary analysis showed that, in general, there does not appear to have been an increase in suicides since the pandemic began, at least in high-income and upper-middle-income countries. Our study adds value because previous studies have reported findings from single countries or regions and their estimates of effect have often not taken account of trends in suicide before the pandemic.

Implications of all the available evidence

Policy responses to prevent the spread of COVID-19 need to balance the benefits of physical distancing, school and workplace closures, and other restrictions against the possible adverse impact of these measures on population mental health and suicide. Our early findings provide some reassurance (at least for high-income and upper-middle-income countries) that COVID-19 risk mitigation measures have not led to population-level increases in suicide rates. Many countries put in place additional mental health supports and financial safety nets, both of which might have buffered any early adverse effects of the pandemic. There is a need to ensure that efforts that might have kept suicide rates down until now are continued, and to remain vigilant as the longer-term mental health and economic consequences of the pandemic unfold. There are some concerning signals that the pandemic might be adversely affecting suicide rates in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, although data are only available in a small minority of these countries and tend to be of suboptimal quality. Even in high-income and upper-middle-income countries, the effect of the pandemic on suicide might vary over time and be different for different subgroups in the population.

We established the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration (ICSPRC) to monitor the global effect of COVID-19 on suicide. We have tracked studies specific to COVID-19 and suicide through a living systematic review,5 and found that most studies have had methodological limitations. Some have relied on data from unconfirmed sources, including reports from Nepal and Thailand based on newspaper articles citing data from the police6, 7 and a secondary source,8 respectively. These reports indicated increases in suicide after the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Other studies have used official suicide statistics for the months since the pandemic began but have made comparisons to equivalent periods without accounting for underlying trends. Studies of this kind in Norway,9 Sweden,10 South Korea,11 Tyrol in Austria,12 Leipzig in Germany,13 and Connecticut in the USA14 showed decreases in suicides, and one in the Evros region of Greece found no change.15 Three separate studies used a similar approach to analyse Japanese suicide statistics: one considered children and adolescents only and found no evidence of an increase;16 and the other two considered all age groups and identified a decrease in the pandemic's early stages,17 but highlighted an upswing in July, 2020.17, 18

Only five studies—from Greece,19 Queensland in Australia,20 Massachusetts in the USA,21 Peru,22 and Japan23—have used official data and accounted for temporal trends. The studies in Greece, Queensland, and Massachusetts found that the observed and expected numbers of suicides did not differ after pandemic responses were introduced.19, 20, 21 The Peruvian study reported a decrease in suicides following stay-at-home orders.22 The Japanese study confirmed fluctuations in suicides and identified a positive association between pandemic-induced employment shocks and suicides.23

The evidence so far is insufficient to indicate what the effect of COVID-19 on suicides has been or will be. It is likely that any effect will vary between and within countries, and over time, depending on factors such as the extent of the pandemic, the public health measures instituted to control it, the capacity of existing mental health services and suicide prevention programmes, and the strength of the economy and relief measures to support those whose livelihoods are affected by the pandemic. There are also multiple other population-level influences on suicide (eg, political unrest, economic challenges, and availability of lethal means) that might operate independently of the pandemic or be exacerbated by it, and these factors might differ across countries.

We did this ICSPRC study to gain a broader understanding of suicide patterns, which we believe is crucial for mitigating the risk of any pandemic-related increases. Specifically we aimed to assess the early effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates around the world.

Methods

Overview

Using real-time suicide data from multiple countries and areas within countries, we did an interrupted time-series analysis to ascertain whether trends in monthly suicide counts changed after the pandemic began. Given the importance of questions about COVID-19 and suicide, we believed that it was crucial to provide evidence from the best available real-time data sources. In many countries, there is a time-lag in official suicide data being released because of the way in which suicide deaths are identified and recorded in vital statistics collections. In these countries, suspected suicides are investigated by a coroner, medical examiner, or other official to confirm the cause and manner of death, with or without an autopsy. The investigation process can be lengthy, resulting in data that are not sufficiently timely to guide suicide prevention actions. Consequently, some countries and areas within countries have developed methods for initial death classification while the investigation is ongoing to produce real-time suicide data. Typically, although not always, these approaches rely on police reports or death certificates as their primary source of evidence for the preliminary classification. These alternative or preliminary data sources are crucial for identifying and responding to any changes in patterns of suicide that might be associated with external events.

Our approach followed the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER; appendix p 1).24 We received approval from the Swansea University Medical School Research Ethics Sub-Committee (2020-0054).

Data inputs

We sought real-time data on suicides from countries as well as from areas within countries to maximise the number of places that could contribute to the overall picture. Establishing real-time suicide data collection systems is difficult, especially on a national level, so restricting our efforts to whole countries would have limited the conclusions we could draw. Real-time suicide data were identified through internet searches, recourse to the scientific literature, and contact with our networks.

We did internet searches between Sept 1 and Nov 1, 2020, to identify relevant data in World Bank countries and economies with more than 3 million residents (n=135).25 We first searched the official websites of these countries’ ministries of health, police agencies, and government-run statistics agencies or equivalents, using the translated search terms “suicide” and “cause of death”. If this search did not yield results, we did a more general internet search using the translated search terms “suicide”, “[name of country]”, “pandemic”, “COVID” and “corona” for publicly reported information (eg, in news reports and on the websites of suicide prevention organisations) that might indicate whether relevant data existed and, if so, how they might be traced.

We also searched the academic literature for studies reporting on suicides before and after the pandemic began through our living review.5 We extracted data from the publications or their cited sources and contacted the authors. We also drew on the knowledge of ICSPRC members (representing 40 countries) and our contacts at WHO and the International Association for Suicide Prevention (IASP).

Publicly available data were accessed online and data that were not publicly available were provided by data custodians.

Data inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, data from a given country or area had to come from an official government source (eg, a government department, agency responsible for collating national statistics, coroners’ court, medical examiners’ office, police department, or university), and be available at a monthly level from at least Jan 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020 (and potentially from as far back as Jan 1, 2016, until as recently as Oct 31, 2020). Our internet searches were restricted to countries with more than 3 million residents for pragmatic reasons, but we relaxed this rule for countries identified through the literature and our networks. Areas within countries could also be included with populations of 3 million residents or fewer.

Data storage and management

We aggregated all data to the monthly level. Data were housed in a safe, secure, password-protected database held at Swansea University using Secure eResearch Platform technology (Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform [ADP]). Per the platform's data protection protocols, access to the data was limited and only made available to JP, AJ, SS, MDPB, VA, DGu, and MJS.

Data analysis

We used interrupted time-series analysis to model the trends in monthly suicides before COVID-19 in each country or area within country, accounting for time trends and seasonality wherever possible. Models were fitted with use of Poisson regression and accounted for possible over-dispersion using a scale parameter set to the model's χ2 value divided by the residual degrees of freedom. We modelled the effect of time as a non-linear predictor, unless this offered no improvement beyond a linear model, in which case we used the linear model instead. Non-linear time trends were estimated by selecting the best fitting model from a series of fractional polynomial models. Seasonality was accounted for with Fourier terms (pairs of sine and cosine functions). We then used each country or area's model to forecast what the trend in suicides from the beginning of the COVID-19 period would have been had COVID-19 not occurred, calculating the expected number of suicides, which represented the counterfactual. We compared this expected number with the observed number of suicides in the same period by calculating rate ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs. In a small number of countries or areas, it was not possible to account for seasonality in the model because we only had pre-COVID-19 data for a single year (Jan 1, 2019, onwards). For these countries, we fitted a model with a linear predictor for time only. Further details of the modelling strategy are provided in the appendix (pp 2–10).

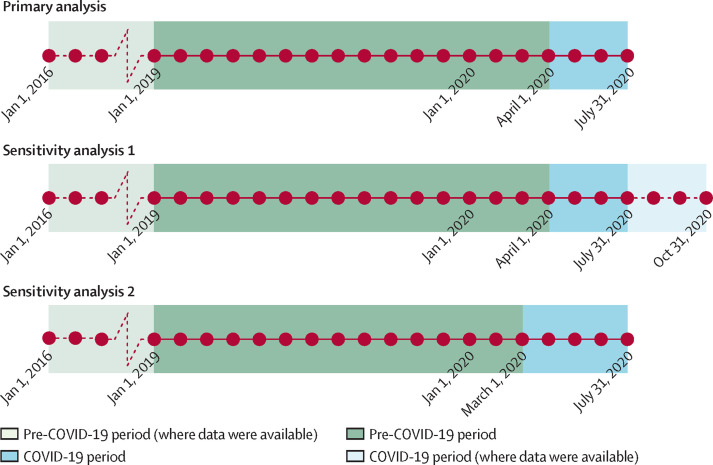

We did a primary analysis and two sensitivity analyses (figure 1 ). In each analysis, we included data from all available months in each country or area in the pre-COVID-19 period. In the primary analysis, we treated April 1, 2020, as the start of the COVID-19 period and censored the data beyond July 31, 2020, in order to maximise data quality, in recognition that there might have been under-enumeration of suicides in the later months with figures being subsequently updated. In the first sensitivity analysis, we retained April 1, 2020, as the start of the COVID-19 period but relaxed the end date to include all data available in the COVID-19 period for each country or area up to Oct 31, 2020. In the second sensitivity analysis, we changed the start of the COVID-19 period to March 1, 2020, and used the original censoring date of July 31, 2020, as the end of the COVID-19 period, recognising that the onset of COVID-19 and associated public health measures varied.

Figure 1.

Pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods as defined in the primary analysis and the two sensitivity analyses

We also did two supplementary analyses. In the first, we repeated the primary analysis using the same methods and date cutoffs, but inflated the number of suicides in each country and area in the months of the COVID-19 period by 5%. In the second, we used data from the Australian state of Tasmania that were aggregated to 3 months (rather than 1 month) but otherwise met our inclusion criteria. In this analysis, we used data from Jan 1, 2019, to Sept 30, 2020, and treated April 1, 2020, as the beginning of the COVID-19 period.

All analyses were done on the Swansea University ADP Secure eResearch Platform using Stata software (version 16.1). The Stata code is available in the appendix (pp 11–17).

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study.

Results

We sourced data from 21 countries (16 high-income countries and five upper-middle-income countries), of which ten had data available for the whole country and 11 had data for a specific area or areas within the country. The table summarises the populations of the countries and areas as well as the dates on which the first stay-at-home orders were implemented.26 The appendix contains details of the source and nature of the data for each country and area (pp 18–23) as well as the raw data (pp 24–28).

Table.

Details of countries and areas within countries included in the study

| Population in 2020 | Beginning of initial stay-at-home period in country26* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High-income countries | |||

| Australia | 25 500 000 | March 24, 2020 | |

| New South Wales | 8 157 700 | .. | |

| Queensland | 5 160 000 | .. | |

| Victoria | 6 689 400 | .. | |

| Austria | 8 900 000 | March 16, 2020 | |

| Carinthia | 560 900 | .. | |

| Tyrol | 757 600 | .. | |

| Vienna | 1 911 200 | .. | |

| Canada | 37 700 000 | March 14, 2020 | |

| Alberta | 4 421 900 | .. | |

| British Columbia | 5 147 700 | .. | |

| Manitoba | 1 380 000 | .. | |

| Chile | 19 100 000 | March 25, 2020 | |

| Croatia | 4 100 000 | March 23, 2020 | |

| England, UK | 56 300 000 | March 24, 2020† | |

| Thames Valley | 2 400 000 | .. | |

| Estonia | 1 300 000 | March 9, 2020 | |

| Germany | 83 800 000 | March 9, 2020 | |

| Cologne and Leverkusen | 1 285 500 | .. | |

| Frankfurt | 753 000 | .. | |

| Leipzig | 591 000 | .. | |

| Italy | 60 500 000 | March 5, 2020† | |

| Udine and Pordenone | 841 300 | .. | |

| Japan | 126 500 000 | April 7, 2020 | |

| Netherlands | 17 100 000 | March 6, 2020 | |

| New Zealand | 4 800 000 | March 21, 2020 | |

| Poland | 37 800 000 | March 31, 2020 | |

| South Korea | 51 200 000 | Feb 23, 2020 | |

| Spain | 46 800 000 | March 14, 2020 | |

| Las Palmas | 1 109 000 | .. | |

| USA | 331 000 000 | March 15, 2020 | |

| California | 39 747 300 | .. | |

| Illinois (Cook County) | 5 106 780 | .. | |

| Louisiana | 4 649 000 | .. | |

| New Jersey | 8 936 600 | .. | |

| Texas (Denton, Johnson, Parker, Tarrant Counties) | 3 374 000 | .. | |

| Puerto Rico‡ | 3 032 200 | .. | |

| Upper-middle-income countries | |||

| Brazil | 212 600 000 | March 14, 2020 | |

| Botucatu | 140 000 | .. | |

| Maceió | 1 020 000 | .. | |

| Ecuador | 17 600 000 | March 17, 2020 | |

| Mexico | 128 900 000 | March 30, 2020 | |

| Mexico City | 9 000 000 | .. | |

| Peru | 33 000 000 | March 15, 2020 | |

| Russia | 146 000 000 | March 5, 2020 | |

| Saint Petersburg | 5 468 000 | .. | |

Countries are categorised according to World Bank income classifications. NA=not applicable.

Date when stay-at-home orders were first applied anywhere in the given country; dates for areas within countries might differ from this.

Date amended by local author(s).

Unincorporated territory of the USA.

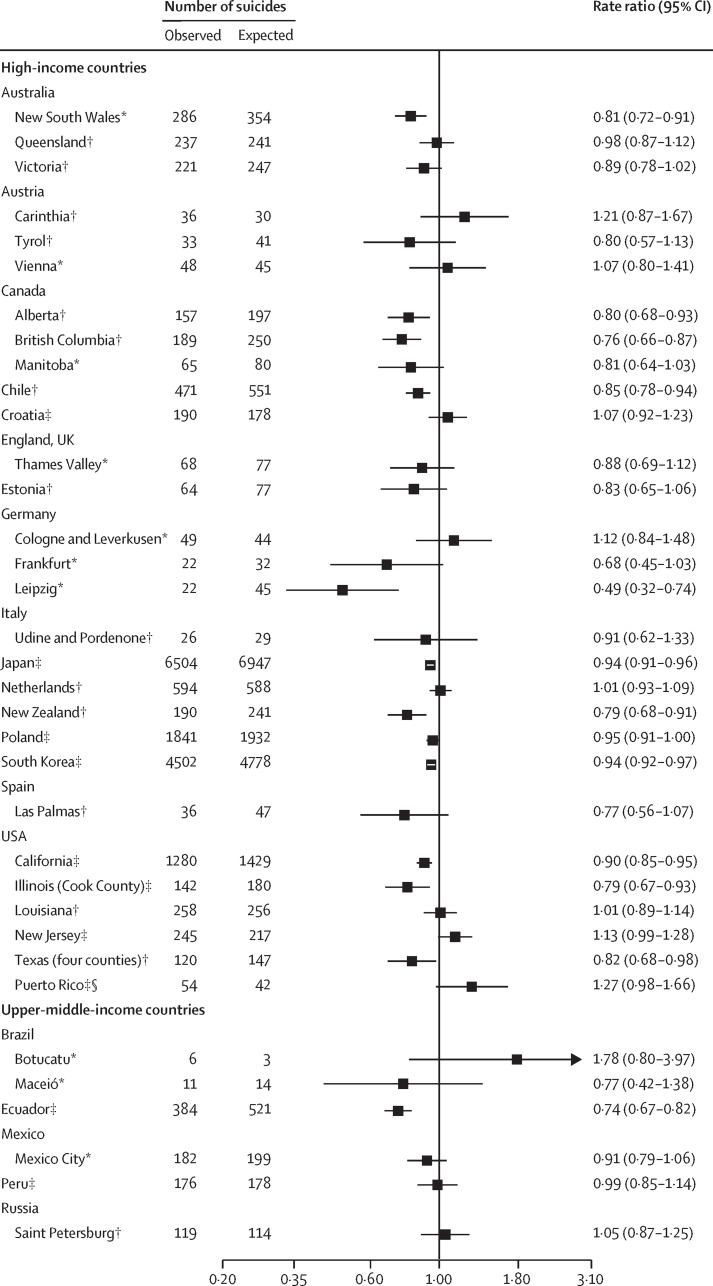

The observed and expected number of suicides for April 1 to July 31, 2020, and the RRs based on these numbers are shown in figure 2 (see appendix pp 4–10 for the coefficients and standard errors of the models underlying the expected number of suicides). The 95% CIs surrounding the RR for each country or area either include the null value of 1·00 or fall below the null value, indicating that there was no evidence of an increase in suicides relative to the expected number during the COVID-19 period in any country or area. There was statistical evidence of a decrease in suicides in 12 countries or areas: New South Wales, Australia (RR 0·81 [95% CI 0·72–0·91]); Alberta, Canada (0·80 [0·68–0·93]); British Columbia, Canada (0·76 [0·66–0·87]); Chile (0·85 [0·78–0·94]); Leipzig, Germany (0·49 [0·32–0·74]); Japan (0·94 [0·91–0·96]); New Zealand (0·79 [0·68–0·91]); South Korea (0·94 [0·92–0·97]); California, USA (0·90 [0·85–0·95]); Illinois (Cook County), USA (0·79 [0·67–0·93]); Texas (four counties), USA (0·82 [0·68–0·98]); and Ecuador (0·74 [0·67–0·82]).

Figure 2.

Observed and expected numbers of suicides in the COVID-19 period based on trends in pre-COVID-19 period by country or area in the primary analysis

The COVID-19 period was defined as April 1 to July 31, 2020, and the pre-COVID-19 period as at least Jan 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020 (with data included from Jan 1, 2016, if available). *Predictor for linear time trend only. †Predictors for linear time trends and seasonality. ‡Predictors for non-linear time trends and seasonality. §Unincorporated territory of the USA.

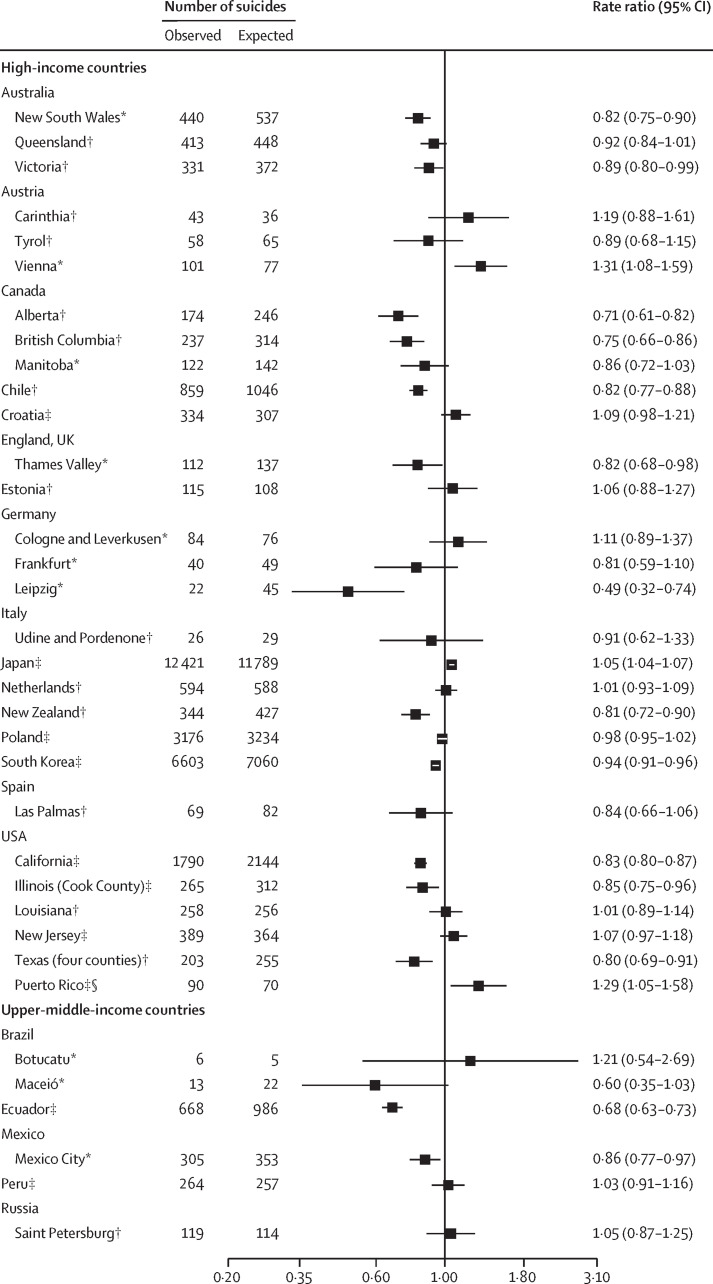

Incorporating data up until the latest month available (to Oct 31, 2020) made little difference to the results from most countries or areas (figure 3 ), with most 95% CIs for the RR estimates below or including 1·00. Victoria, Australia (0·89 [0·80−0·99]); Thames Valley, England, UK (0·82 [0·68−0·98]); and Mexico City, Mexico (0·86 [0·77−0·97]) showed significant decreases that were not seen in the primary analysis. There were three exceptions to the picture of no change or decreases in suicides: Vienna showed statistical evidence of an increase in suicides (1·31 [1·08–1·59]) relative to the expected number when the additional months were included, as did Japan (1·05 [1·04–1·07]) and Puerto Rico (1·29 [1·05–1·58]). In each case, the latest month for which data were available was October.

Figure 3.

Observed and expected numbers of suicides in COVID-19 period based on trends in pre-COVID-19 period by country or area in the first sensitivity analysis

The COVID-19 period was defined as April 1 to at least July 31, 2020 (with data included up to Oct 31, 2020, if available), and the pre-COVID-19 period as at least Jan 1, 2019, to March 31, 2020 (with data included from Jan 1, 2016 if available). *Predictor for linear time trend only. †Predictors for linear time trends and seasonality. ‡Predictors for non-linear time trends and seasonality. §Unincorporated territory of the USA.

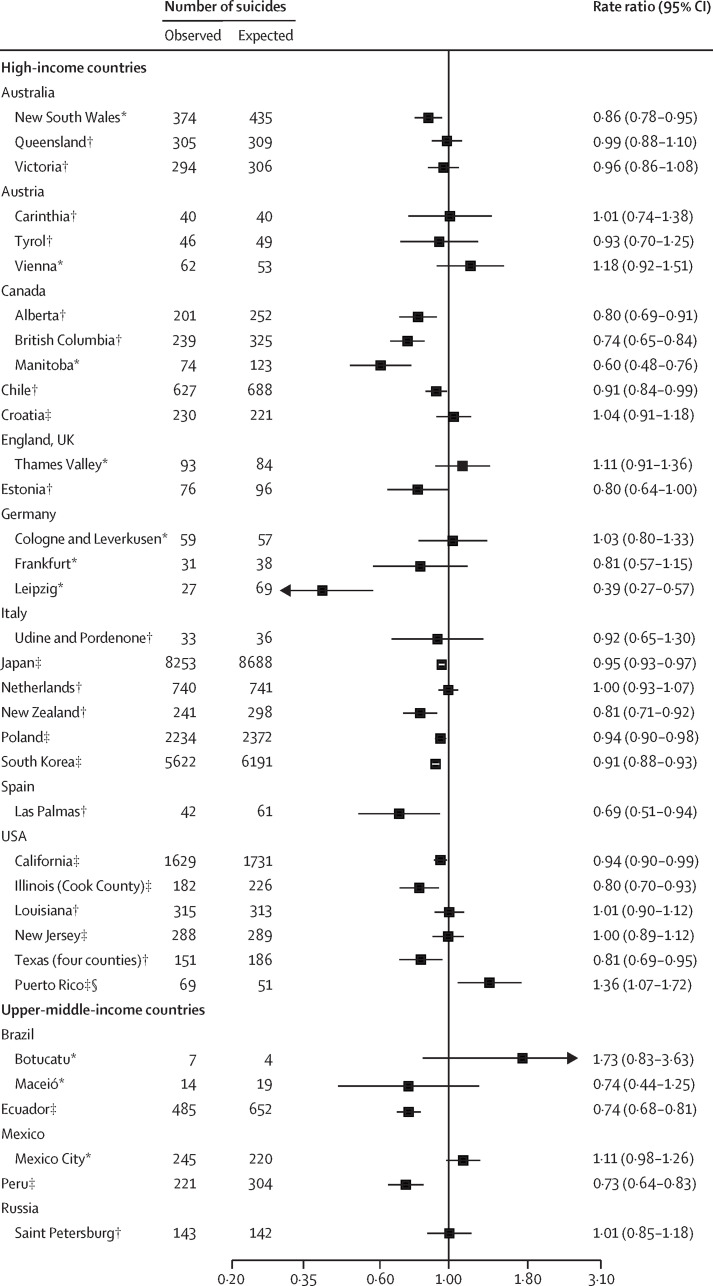

The results of the second sensitivity analysis, in which the pandemic's first day was defined as March 1 rather than April 1, 2020 (figure 4 ), were also similar to those from our primary analysis. Again, there was evidence of a decreased risk of suicide in several additional countries or areas over and above those observed in our primary analysis: Manitoba, Canada (0·60 [0·48−0·76]); Poland (0·94 [0·90−0·98]); Las Palmas, Spain (0·69 [0·51−0·94]); and Peru (0·73 [0·64−0·83]). There was no evidence of any increase in suicides relative to the expected number during this COVID-19 period for any country or area except Puerto Rico (1·36 [1·07–1·72]).

Figure 4.

Observed and expected numbers of suicides in COVID-19 period based on trends in pre-COVID-19 period by country or area in the second sensitivity analysis

The COVID-19 period was defined as March 1 to July 31, 2020, and the pre-COVID-19 period as at least Jan 1, 2019, to Feb 29, 2020 (with data included from Jan 1, 2016, if available). *Predictor for linear time trend only. †Predictors for linear time trends and seasonality. ‡Predictors for non-linear time trends and seasonality. §Unincorporated territory of the USA.

Our two supplementary analyses also showed consistent findings. Inflating the suicide numbers in the COVID-19 period by 5% made little difference to the results (appendix p 29), with only two areas showing statistical evidence of an increase in suicides where this had not been the case previously: New Jersey, USA (RR 1·18 [95% CI 1·05–1·34]) and Puerto Rico (1·34 [1·03–1·74]). When we analysed the 3-monthly data from Tasmania, the findings were similar to those from the other Australian states, with no evidence of any increase in suicides in the COVID-19 period (RR 0·74 [95% CI 0·53–1·02]).

Discussion

In general, based on the primary analysis, there does not appear to have been an increase in risk of suicide during the pandemic's early months in the 21 countries for which we had data, and a number of countries or areas appear to have seen fewer suicides relative to the expected number.

Our findings align with those of other published studies from high-income and upper-middle-income countries, in which there were either decreases or no changes in suicide rates as a function of the pandemic.9–15,19–22 Our findings are also consistent with emerging reports in the grey literature from various countries (eg, England).27 In some cases, this consistency is not surprising because we used the same data sources, but the fact that we found similar patterns in many other countries increases our confidence in this finding.

The lack of increase in suicides since the pandemic began could be attributed to various factors. First, there was an early emphasis on the potential adverse effects of stay-at-home orders, school closures, and business shut downs. Empirical evidence began to emerge from some countries that self-reported levels of depression, anxiety, and suicidal thinking were heightened during the initial stay-at-home periods,1 but this does not appear to have translated into increases in suicides, at least in the countries in our study. In some countries, governments responded rapidly to the threat to mental health, implementing recommended approaches such as bolstering mental health services.28 Maintaining this emphasis on accessible, high-quality mental health care is crucial.

Second, certain protective factors might have been operating in the pandemic's early months. Communities might have actively tried to support at-risk individuals, people might have connected in new ways, and some relationships might have been strengthened by households spending more time with each other.28 For some people, everyday stresses might have been reduced during stay-at-home periods, and for others the collective feeling of “we’re all in this together” might have been beneficial.

Finally, many countries rapidly enacted fiscal support initiatives to buffer the pandemic's economic consequences. In many cases, this support is now being reduced or withdrawn. As it lapses, previously protected populations might face increasing stress. Suicide rates can rise during times of economic recession,29 so it is possible that the pandemic's potential suicide-related effects are yet to occur.

Vienna, Japan, and Puerto Rico were outliers in parts of our analysis. Although they showed no evidence of an increased risk of suicide in our primary analysis, we observed a significantly increased risk in all three when we extended the observation period to Oct 31, 2020, and in Puerto Rico we noted an increase when we brought forward the pandemic's start date from April 1 to March 1, 2020. Additional contextual factors might have operated in these countries—for example, in Japan, several widely reported celebrity suicides that occurred during the pandemic might have exerted an influence; and Puerto Rico has been in a deep recession since 2006, so pre-existing high levels of poverty might have exacerbated the pandemic's economic effects.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to combine data from multiple countries to examine the early effects of COVID-19 on suicide, taking account of underlying trends. The study involved a systematic search process and overcame the delays inherent in vital statistic collection by using real-time data from numerous official sources. However, it did not represent low-income or lower-middle-income countries, which account for 46% of the world's suicides and might have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic. Very few of these countries have good-quality vital registration systems and still fewer collect real-time suicide data.30 In our search, we identified unofficial real-time data from two lower-middle-income countries (Myanmar and Tunisia) and one low-income country (Malawi) that could not be disaggregated to the monthly level. We were unable to verify or use these data in our analyses, but they were concerning for two of these countries. In Malawi, there was reportedly a 57% increase in January–August, 2020, compared with January–August, 2019, and in Tunisia there was a 5% increase in March–May, 2020, compared with March–May, 2019. By contrast, in Myanmar, there was a 2% decrease in January–June, 2020, compared with January–June, 2019.

Another limitation is that data quality might have been an issue in the countries and areas in our study. Data from the most recent months in any given country or area might have been the least reliable and the most likely to represent undercounts, especially if COVID-19 disrupted data-collection processes. We attempted to overcome this problem by using July 31, 2020, as the end date in our primary analysis, and only using more recent months (to Oct 31, 2020) in the first sensitivity analysis. If the data in the later months were artificially low, we might have expected to see countries or areas that showed no difference in suicides in the primary analysis recording a decrease in this sensitivity analysis, but this only occurred in Victoria, Australia; Thames Valley, England, UK; and Mexico City, Mexico. Similarly, inflating the number of suicides in each month of the COVID-19 period by 5% (which might be the typical magnitude of any increase if later figures were updated) made little difference. Only two areas showed statistical evidence of an increase in suicides where this had not been the case previously: New Jersey (USA) and Puerto Rico.

In addition, various factors might have influenced the power and precision of our models. In particular, low numbers of timepoints and low numbers of monthly suicides in given countries or areas might have resulted in models with relatively poorer power and precision, with the effect of biasing the findings to the null and suggesting that there was no change in the number of monthly suicides from the pre-COVID-19 period to the COVID-19 period when in fact there might have been an increase or a decrease. Only five areas had both the minimum number of pre-COVID-19 timepoints (January, 2019, to March, 2020) and low numbers of monthly suicides and showed no change in suicide risk in our primary analysis: Vienna, Austria; Cologne and Leverkusen, Germany; Frankfurt, Germany; Botucatu, Brazil; and Maceio, Brazil. The findings from these five areas should be interpreted with caution.

We were unable to stratify the data by age, sex, or ethnicity, and the pandemic might have a differential effect on suicides in certain demographic groups (eg, women and girls,17, 18 children and adolescents,17 and ethnic minorities14). We were also unable to explore any temporal changes in suicide methods. Additionally, we could not consider external factors that might have influenced suicide patterns in different countries or areas, including varying public health measures or economic support packages. We are planning future studies to address these questions.

We relied on area-within-country data for 11 countries. We included these data to ensure representation from as many countries as possible and to avoid generating a picture that was biased towards better-resourced countries. We deliberately did not extrapolate from these areas to whole countries because we were aware that they were sometimes small and might have had unique suicide profiles. However, some of these areas would have been expected to account for a large proportion of the suicides in the given country, based on their population size and their historical suicide statistics (eg, suicides in New South Wales, Queensland, and Victoria typically represent 75% of all suicides in Australia)31 and others had larger populations than some of the other included countries (eg, California had a population of 39·7 million people). Additionally, data from the areas within these countries showed similar patterns to those from relevant areas studied elsewhere. For example, studies done in Massachusetts and Connecticut, USA, showed no increase in suicide numbers after the pandemic began,14, 21 which is in line with our findings from the US jurisdictions for which we had data. Similarly, the 3-monthly data from Tasmania that we analysed separately showed no increase in suicides, consistent with the findings from the other Australian states.

We used the same date in a given analysis to distinguish the pre-COVID-19 period from the COVID-19 period for all countries (April 1 or March 1, 2020), potentially underestimating any effect of COVID-19 in countries or areas with an earlier onset of the pandemic or public health protection measures. We considered using the date of the initial stay-at-home order to distinguish the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 periods, but areas within a given country might have introduced stay-at-home orders at different times. Additionally, because we had monthly suicide counts, we would have had to convert the date of the initial stay-at-home order to the beginning of the month in question or the next month. These dates fell between Feb 23 and April 7, so between them the analyses covered all periods.

Our study is the first to examine suicides occurring in the COVID-19 context in multiple countries. It offers a broadly consistent picture, albeit from high-income and upper-middle-income countries, of suicide numbers remaining unchanged or declining in the pandemic's early months. This picture is neither complete nor final, but serves as the best available evidence on the pandemic's effects on suicide so far.

We need to continue to monitor real-time data and be alert to any increases in suicide, particularly as the pandemic's full economic consequences emerge. We need to understand what has kept suicide numbers down during the pandemic's early months, and what drives any increases if they do occur. We also need to recognise that suicide is not the only indicator of the negative mental health effects of the pandemic; levels of community distress are high and we need to ensure that people are supported. We need to redouble our efforts to understand the pandemic's effects on suicides in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, and we need to make sure that we communicate our findings to governments and communities in safe, non-sensationalist ways.32

Policy makers should heed the value of high-quality, timely suicide data in suicide prevention efforts, and should prioritise mitigation of suicide risk factors associated with COVID-19 and take decisive action (eg, by resourcing mental health services and providing financial safety nets) to prevent the possible longer-term detrimental effects of the pandemic on suicide.

For more on ICSPRC see https://www.iasp.info/COVID-19_suicide_research.php

Data sharing

The statistical code and raw data are available in the appendix (pp 18–25).

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the help that the ICSPRC has received from IASP in establishing and supporting its activities. This study was supported by the ADP, which is funded by MQ Mental Health Research Charity (grant reference MQBF/3 ADP). ADP and the authors acknowledge the data providers who supplied the datasets enabling this study. The views expressed are entirely those of the authors and should not be assumed to be the same as those of ADP or MQ Mental Health Research Charity. The authors acknowledge the Queensland Mental Health Commission for funding the Queensland Suicide Register from 2013 to the present day and Queensland Health for funding the register from 1990–2013. The authors acknowledge the Coroners Court of Queensland and the Victorian Department of Justice and Community Safety as the source organisations of data, and the National Coronial Information System as the database source of data. The authors also acknowledge Queensland Police Service staff for sending police reports of suspected suicides. The authors would also like to thank the team working on the living systematic review of COVID-19 and suicidal behaviour: Emily Eyles, Luke McGuinness, Babatunde K Olorisade, Lena Schmidt, Catherine MacLeod Hall, and Julian Higgins (University of Bristol), and Chukwudi Okolie and Dana Dekel (University of Swansea). JP is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (GNT1173126). AJ is funded by MQ (MQBF/3) and the Medical Research Council (MC_PC_17211). MDP-B is funded by Health and Care Research Wales (CA04). VA is supported by Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. EA is supported by the Health Research Board Ireland (IRRL-2015-1586). AB is supported by the EU Erasmus+ Strategic Partnership Programme (2019-1-SE01-KA203-060571). NK is supported by the University of Manchester, Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre. OJK is supported by a Senior Postdoctoral Fellowship from Research Foundation Flanders (FWO 1257821N). DK is funded by the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research, University of Bristol, and the Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund. TN has been supported by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund through project COV20-027. RCO’C reports grants from Samaritans, Scottish Association for Mental Health, Mindstep Foundation, NIHR, Medical Research Foundation, Scottish Government, and NHS Health Scotland/Public Health Scotland. MRP is supported in part by a grant from the Global Alliance of Chronic Diseases and the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371502). PLP is an employee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria. AR, CR-L, and CS are responsible for Frankfurter Projekt zur Prävention von Suiziden mittels Evidenz-basierten Maßnahem (FraPPE; Frankfurt Project to prevent suicides using evidence-based measures), which is funded by the German Ministry. MS is supported by Academic Scholar Awards from the Departments of Psychiatry at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and the University of Toronto. MW is funded by a Focus Grant from American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (IIG-0-002-17). DGu is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. MJS is a recipient of an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT180100075).

Editorial note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published tables, figures, and institutional affiliations.

Contributors

JP, AJ, and DGu conceptualised, designed and led the study, with assistance from MJS. SS, MDP-B, and VA conducted the internet searches for data and JP, AJ, and DGu followed up leads through the ICSPRC and IASP networks, assisted by MJS and TN. Additional data were sourced or provided by the following authors: PA-A, AB, JMB, PB, GC, MC, DCo, DCr, CD, EAD, JD, MDP-B, JSF, SF, AG, DGe, RGe, RGi, DGu, KH, AJ, JK, KK, SL, EM-R, NN, HO, GP, PLP, PQ, AR, CR, DR, CR-L, VR, BS, CS, MS, NS, MU, and RTW. JP, SS, MDP-B and VA were responsible for data verification, management and storage. MJS did the analysis. JP prepared the first draft of the manuscript with input from AJ, DGu, and MJS. All authors interpreted data and made critical intellectual revisions to the manuscript. Access to the data were limited for data protection reasons and only made available to JP, AJ, SS, MDP-B, VA, DGu, and MJS.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:468–471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zortea TC, Brenna CTA, Joyce M, et al. The impact of infectious disease-related public health emergencies on suicide, suicidal behavior, and suicidal thoughts. Crisis. 2020 doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000753. published online Oct 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leaune E, Samuel M, Oh H, Poulet E, Brunelin J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic rapid review. Prev Med. 2020;141 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John A, Okolie C, Eyles E, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: a living systematic review [version 1] F1000 Res. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.25522.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acharya SR, Shin YC, Moon DH. COVID-19 outbreak and suicides in Nepal: urgency of immediate action. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020963150. published online Sept 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poudel K, Subedi P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on socioeconomic and mental health aspects in Nepal. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:748–755. doi: 10.1177/0020764020942247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ketphan O, Juthamanee S, Racal S, Bunpitaksakun D. The mental health care model to support the community during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. Belitung Nurs J. 2020;6:152–156. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin P, Mehlum L. National observation of death by suicide in the first 3 months under COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143:92–93. doi: 10.1111/acps.13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rück C, Mataix-Cols D, Malki K, et al. Will the COVID-19 pandemic lead to a tsunami of suicides? A Swedish nationwide analysis of historical and 2020 data. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.10.20244699. published online Dec 11. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim AM. The short-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on suicides in Korea. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deisenhammer EA, Kemmler G. Decreased suicide numbers during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radeloff D, Papsdorf R, Uhlig K, Vasilache A, Putnam K, von Klitzing K. Trends in suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in a major German city. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e16. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell TO, Li L. State-level data on suicide mortality during COVID-19 quarantine: early evidence of a disproportionate impact on racial minorities. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karakasi M-V, Kevrekidis D, Pavlidis P. The role of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on suicide rates: preliminary study in a sample of the Greek population. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2021;42:99–100. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isumi A, Doi S, Yamaoka Y, Takahashi K, Fujiwara T. Do suicide rates in children and adolescents change during school closure in Japan? The acute effect of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:229–238. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueda M, Nordström R, Matsubayashi T. Suicide and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.06.20207530. published online Dec 20. (preprint, version 5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandoros S, Theodorikakou O, Katsadoros K, Zafeiropoulou D, Kawachi I. No evidence of increase in suicide in Greece during the first wave of COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.13.20231571. published online Nov 16. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leske S, Kõlves K, Crompton D, Arensman E, de Leo D. Real-time suicide mortality data from police reports in Queensland, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:58–63. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faust J, Shah S, Du C, Li S, Lin Z, Krumholz H. Suicide deaths during the stay-at-home advisory in Massachusetts. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calderon-Anyosa RJC, Kaufman JS. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Prev Med. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ando M, Furuichi M. The impact of COVID-19 employment shocks on suicide and poverty alleviation programs: an early-stage investigation. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.16.20232850. published online Nov 18. (preprint). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet. 2016;388:e19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Bank Population: all countries and economies. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL

- 26.Our World in Data Stay-at-home requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/stay-at-home-covid?stackMode=absolute®ion=World

- 27.Appleby L, Richards N, Ibrahim S, Turnbull P, Rodway C, Kapur N. Suicide in England in the COVID-19 pandemic: early figures from real time surveillance. SSRN 2021, published online Feb 8. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Wasserman D, Iosue M, Wuestefeld A, Carli V. Adaptation of evidence-based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:294–306. doi: 10.1002/wps.20801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang S-S, Stuckler D, Yip P, Gunnell D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2019. Suicide in the world: global health estimates.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326948 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Australian Bureau of Statistics Causes of death, Australia. 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/latest-release#data-download

- 32.Hawton K, Marzano L, Fraser L, Hawley M, Harris-Skillman E, Lainez YX. Reporting on suicidal behaviour and COVID-19-need for caution. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:15–17. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30484-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The statistical code and raw data are available in the appendix (pp 18–25).