Abstract

Purpose

Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people’s mental health is an increasing priority. Studies to date are largely surveys and lack meaningful involvement from service users in their design, planning, and delivery. The study aimed to examine the mental health status and coping strategies of young people during the first UK COVID-19 lockdown using coproduction methodology.

Methods

The mental health status of young people (aged 16–24) in April 2020 was established utilizing a sequential explanatory coproduced mixed methods design. Factors associated with poor mental health status, including coping strategies, were also examined using an online survey and semi-structured interviews.

Results

Since the lockdown, 30.3% had poor mental health, and 10.8% had self-harmed. Young people identifying as Black/Black-British ethnicity had the highest increased odds of experiencing poor mental health (odds ratio [OR] 3.688, 95% CI .54–25.40). Behavioral disengagement (OR 1.462, 95% CI 1.22–1.76), self-blame (OR 1.307 95% CI 1.10–1.55), and substance use (OR 1.211 95% CI 1.02–1.44) coping strategies, negative affect (OR 1.109, 95% CI 1.07–1.15), sleep problems (OR .915 95% CI .88–.95) and conscientiousness personality trait (OR .819 95% CI .69–.98) were significantly associated with poor mental health. Three qualitative themes were identified: (1) pre-existing/developed helpful coping strategies employed, (2) mental health difficulties worsened, and (3) mental health and nonmental health support needed during and after lockdown.

Conclusion

Poor mental health is associated with dysfunctional coping strategies. Innovative coping strategies can help other young people cope during and after lockdowns, with digital and school promotion and application.

Implications and Contribution.

Using a methodologically rigorous sequential explanatory mixed methods coproduced approach, this study found a significant association between poor mental health and dysfunctional coping strategies employed during COVID-19. Findings have implications for the application of self-management, peer support, and digital support alternatives during and after lockdowns.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a worldwide pandemic, with 1,845,408 deaths reported as of January 4, 2021 [1]. The UK now has over 75,137 coronavirus-related deaths [1], the sixth-highest worldwide. This figure, largely comprised adults aged 24 or over. Although young people (aged 16–24) appear to be at lower risk from worse COVID-19 outcomes than older age groups [2], they have still been subject to stringent public health measures of social distancing. Significant changes to daily routines (e.g., school, university, and employment attendance), and feeling isolated from friends and family have meant that young people are likely to experience adverse mental health consequences both during and after social distancing measures have been lifted [3]. Indeed, 75% of all mental health conditions start before the age of 24 [4]. There is a high rate of self-harm in young people, and suicide is the second leading cause of death in this group [5]. Well-established risk factors for mental disorders include genetic predisposition to psychiatric disorder, substance use, and maladaptive personality traits [6]. Other social risk factors include social isolation, loneliness, family conflict, family bereavement, inadequate or inappropriate provision of education, academic failure, and community disorganization [6]. All these factors could occur during COVID-19 lockdown, which creates the need to explore the mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people [3].

Studies that have examined the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health outcomes are extensive, but most published studies have focused on adults or countries outside the UK [7,8]. Most of these studies have shown a decline in mental health due to COVID-19. For example, a U.S. cross-sectional study found a higher incidence of mental health distress in April 2020 compared with a matched sample in 2018 [9]. In the UK, a longitudinal study found that there were higher levels of depression and anxiety early in the lockdown compared to when restrictions eased, and being younger was a risk factor [10]. Similarly, a cross-sectional study on the impact of COVID-19 self-isolation/social distancing found young age (18–24) in particular, was significantly associated with experiences of poor mental health in 932 participants [11]. Another UK survey identified the needs of young people with existing mental health conditions during COVID-19 [12]. Other UK studies are ongoing [7,8]. An exception to studies showing increases in mental health concerns is a recent report of school-age children, which found that anxiety during lockdown had decreased rather than increased, particularly among students with low prepandemic school, peer and family connectedness [13]. In young people age 16–24, COVID-19 has disrupted the transition between the familiarity of school and family life and the challenges of adulthood. It is therefore imperative to understand how young people have responded and adapted to these changes.

A unique aspect of our study, to our knowledge, was being young person-led and coproduced with young people throughout all research stages. There has been a significant drop in meaningful patient and public involvement (PPI) since COVID-19 [14], and truly coproduced research has not been conducted. This is likely due to the desire for rapid results to inform policy and in-person PPI not being possible [15]. However, we believe it is crucial to continue to follow guidance [16] and ensure young people are meaningfully involved throughout research [17]. Our rapid prioritization exercise with young people during the lockdown in the UK led to our focus to identify how the mental health and coping strategies of young people changed over time following the lockdown. Coping strategies vary in young people, from adaptive emotion-focused, problem-solving to dysfunctional strategies. Notably, social isolation and avoidant behavior have been deemed to be maladaptive coping strategies themselves under nonpandemic conditions [18]. Therefore, there is a critical need to explore this complex area. Our study is the first to systematically examine mental health status and coping strategies in young people using a coproduced mixed methods design at a specific point in time during the first UK COVID-19 lockdown (March 23 to May 28, 2020).

Method

Research design

A sequential explanatory coproduced mixed methods design [19], drawing on pragmatism [20] and coproduction methodology [21,22], was chosen to examine mental health characteristics and associations between these characteristics, coping strategies, and other related factors. Experience of the COVID-19 lockdown adopted safe and unsafe coping strategies, and recommendations for other young people were also explored. Coproduction methodology was applied across all research stages, including identifying the research question, ethics, design, management, data collection, analysis, and dissemination (Appendix A). In practice, this meant young people with experience of mental health difficulties were involved as equal research partners (i.e., coresearchers), sharing decision-making, power, and responsibility throughout [23]. The survey (QUANT) occurred first, followed by analysis interpretation, which then informed in-depth semi-structured interviews (QUAL) (Appendix B). Qualitative data analysis followed, which helped to explain the quantitative findings [21].

Survey participants

Convenience samples of young people aged 16–24 years with access to the internet were approached and recruited. They were included if they currently lived in the UK and had proficient use of the English language. We strived to ensure a representative sample by developing an engaging poster and going through various channels to recruit diverse groups of young people (e.g., students, people from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities, those living in urban/rural environments). We advertised the study using various media, including email distribution lists; social media platforms, including Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook; young people’s networks (e.g., GenerationR, Imperial Young People’s Advisory Network, TalkLife); through charity contacts (e.g., Leaders Unlocked, The McPin Foundation) and independent third parties.

Quantitative data collection

The survey primarily included standardized measures that had high validity and reliability (Appendix C). The coresearchers tested it to check it took no longer than 15–20 minutes to complete to help with engagement. The survey was uploaded to REDCap and was open between April 24 and May 13, 2020 (Appendix B). Participants were entered into a £50 e-voucher prize draw.

Qualitative data collection

Participants were randomly selected from those who completed the survey and indicated they were willing to be interviewed. They were approached between June 3 and June 28, 2020. All survey participant IDs were entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The RAND (random number generator) command was utilized to create a randomly allocated number for each ID. The IDs were ordered and allocated to all interviewers alphabetically. Participants were then approached via email. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by researchers (LD, CK) and coresearchers (CC, LC, JJ) on Microsoft Teams at a time that was convenient for the participant. Participants were given a choice of whether to be interviewed with video, audio only, or using the chat text function. Interviews stopped once data saturation was achieved. Each participant received a £20 e-voucher for their time.

Measures

We collected demographic information such as age, gender, ethnicity, relationship status, household makeup and type, access to green space and mental health diagnosis (Appendix C). Validated measures were used to measure mood (Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PHQ-9) [24], sleep (Sleep Condition Indicator; SCI) [25], positive and negative affect (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PANAS) [26], personality type (Ten-Item Personality Inventory; TIPI) [27,28] and optimism (Life-Orientation Test-Revised; LOT-R) [29,30] (Appendix C). Self-harm was measured using two questions taken from the Suicide Ideation and Behavior Interview [31]. The Coronavirus Impact Scale (CIS) was established specifically to measure the impact of COVID-19 on various areas, including routine, stress, and sleep [32]. Brief COPE Inventory was used to assess coping strategies [33]. Items were assigned to 14 adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies, including acceptance, emotional support, humor, positive reframing, religion, active coping, instrumental support, planning, behavioral disengagement, denial, self-distraction, self-blame, substance use, and venting. We added three additional items that became eating-related coping strategies. A higher score on each scale reflected more frequent use of that coping strategy.

Statistical analysis

The data was screened prior to the main analysis. We ran frequencies and descriptive statistics on all variables to check for errors, conducted consistency checks and treated missing responses. If a full measure response was missing, the participant was removed from the main analysis. Descriptive data were used for the sample characteristics (counts and proportions). Variables were recoded to allow for more sensible comparisons. For example, gender was changed from five categories (female, male, nonbinary, gender fluid and other) to include male, female and other. Mental health status was defined as poor if PHQ-9 score ≥15 and/or self-harm present and/or CIS scores indicating persistent worries/severe stress-related symptoms. A dummy variable was assigned (0 = no and 1 = yes) to those who completed all questions. Subsequent analyses were conducted across the two groups. Chi-squared tests and t-tests were conducted to determine associations between dichotomous and continuous data as appropriate. A multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify key predictors of poor mental health (dependent variable), including sociodemographic variables, sleep, affect, coping strategy, personality traits and optimism (independent variables). For ensuring the model best fit, a priori blocks were analyzed systematically. We first included sociodemographic variables previously associated with poor mental health (age, gender, ethnicity, and relationship status). These variables were retained throughout. We then added our independent variables (sleep, positive and negative affect, and coping strategy). Variables that were significant and/or added to the variance explained were retained. Next, we added exploratory variables, including personality traits, and optimism. The final model was then guided by Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Quantitative analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0.

Qualitative analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data were then subjected to coproduced thematic analysis [34]. Each researcher and coresearcher read, familiarized themselves with and coded their own transcripts. Different digital software helped manage the next stages of the process (e.g., Jamboard, Trello, and Miro). Jamboard was used to collate initial codes and data impressions that were incorporated into an initial coding framework. This framework was then used by all interviewers to analyze subsequent transcripts. After this initial coding, all interviewers separately added all codes onto a Trello board for all to view online. All interviewers attended two 2.5-hour virtual meetings to refine codes and finalize themes. We met a further time online to coproduce a thematic map in Miro.

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Imperial Research Ethics committee (ICREC ref: 20IC914) on 20/04/2020. The study was registered with COVID MINDS.

Results

Quantitative results

Survey responses

Eight-hundred and 10 participants clicked on the survey link, and 796 participants completed the demographic questionnaire (Table 1 ). There was some drop out across the remaining questionnaires. Six hundred and 41 participants completed the full survey (80.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic survey characteristics (n = 796)a

| Total |

|

|---|---|

| N [%] | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 159 [20.019] |

| Female | 628 [78.9] |

| Other (nonbinary, gender fluid, prefer not to say) | 9 [1.1] |

| Age groupb | |

| 16–18 | 360 [45.2] |

| 19–21 | 190 [23.9] |

| 22–24 | 245 [30.8] |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 593 [74.5] |

| Black/Black-British | 21 [2.6] |

| Asian/Asian-British | 111 [13.914] |

| Mixed | 41 [5.2] |

| Arab | 10 [1.3] |

| Other | 13 [1.6] |

| Prefer not to say | 7 [0.9] |

| Location | |

| England | 751 [94.3] |

| Scotland | 21 [2.6] |

| Wales | 13 [1.6] |

| Northern Ireland | 7 [0.9] |

| Not specified | 4 [0.5] |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 494 [62.1] |

| In a relationship | 262 [32.9] |

| It is complicated | 24 [3.0] |

| Engaged | 7 [0.9] |

| Married | 4 [0.5] |

| Civil partnership | 1 [0.1] |

| Not disclosed | 4 [0.5] |

| Number of people in a household | |

| One person | 27 [3.4] |

| Two people | 89 [11.2] |

| Three people | 160 [20.1] |

| Four people | 298 [37.4] |

| Five people | 147 [18.5] |

| Six or more people | 75 [9.4] |

| Household | |

| Living with family | 628 [78.9] |

| Living with partner/spouse | 59 [7.4] |

| Living with peers | 71 [8.9] |

| Living alone | 24 [3.0] |

| Other | 14 [1.8] |

| Number of rooms in a householdc | |

| 0 | 7 [0.9] |

| 1 | 43 [5.4] |

| 2 | 88 [11.1] |

| 3 | 152 [19.1] |

| 4 | 133 [16.7] |

| 5 | 139 [17.5] |

| 6 or more | 234 [29.4] |

| COVID-19 related living and routine | |

| Self-isolating | 98 [12.3] |

| Staying at home but social distancing | 630 [79.1] |

| Essential worker so not self-isolating or social distancing | 53 [6.7] |

| Other | 15 [1.9] |

| Access to green/outside space | |

| Access to own garden | 661 [83.0] |

| Access to balcony | 60 [7.5] |

| Access to nearby park | 517 [64.9] |

| Access to other green/outside space | 185 [23.2] |

| No access | 19 [2.4] |

| COVID-19 impact (n = 728) | |

| Routine | |

| None | 7 [1.0] |

| Mild | 43 [5.9] |

| Moderate | 201 [27.6] |

| Severe | 477 [65.5] |

| Family Income/employment | |

| None | 266 [36.5] |

| Mild | 319 [43.8] |

| Moderate | 128 [17.6] |

| Severe | 15 [2.1] |

| Food access | |

| None | 307 [42.2] |

| Mild | 361 [49.6] |

| Moderate | 58 [8.0] |

| Severe | 2 [0.3] |

| Access to extended family/nonfamily social support (n = 727) | |

| None | 77 [10.6] |

| Mild | 319 [43.9] |

| Moderate | 293 [40.3] |

| Severe | 38 [5.2] |

| Stress (n = 727) | |

| None | 57 [7.8] |

| Mild | 292 [40.2] |

| Moderate | 285 [39.2] |

| Severe | 93 [12.8] |

| Sleep (n = 727) | |

| None | 199 [27.4] |

| Mild | 221 [30.4] |

| Moderate | 202 [27.8] |

| Severe | 105 [14.4] |

| Stress and discord in a family (n = 727) | |

| None | 177 [24.3] |

| Mild | 415 [57.1] |

| Moderate | 112 [15.4] |

| Severe | 23 [3.2] |

| Access to extended family/nonfamily social support (n = 727) | |

| None | 77 [10.6] |

| Mild | 319 [43.9] |

| Moderate | 293 [40.3] |

| Severe | 38 [5.2] |

| Medical health care access (n = 728) | |

| Not applicable | 196 [26.9] |

| None | 212 [29.1] |

| Mild | 165 [22.7] |

| Moderate | 140 [19.2] |

| Severe | 15 [2.1] |

| Mental health treatment access (n = 727) | |

| Not applicable | 317 [43.6] |

| None | 263 [36.2] |

| Mild | 85 [11.7] |

| Moderate | 42 [5.8] |

| Severe | 20 [2.8] |

| Personal diagnosis (n = 708) | |

| None | 600 [84.7] |

| Mild symptoms | 106 [15.0] |

| Moderate | 2 [0.3] |

| Mental health diagnosis | |

| Yes | 161 [20.2] |

| No | 635 [79.8] |

One person was excluded from this analysis as they only answered one question. The remaining questions were missing.

1 person's age missing

Excluding rooms people sleep in.

Participant characteristics

The mean age of participants was 19.6 years (SD 2.7). There was a higher proportion of nonwhite ethnic groups than the UK population, with 26% of participants identifying themselves as BAME. Participants were mainly female (78.9%), from England (94.0%), single (62.1%), living at home with family (78.9%), social distancing (79.1%), and had access to a garden at home (83.0%). Around two-thirds of participants were living with four or more people (65.3%).

Almost all participants indicated COVID-19 had a moderate-severe impact on their routine (n = 728; 93.1%). Most experienced mild concerns with other lifestyle factors impacted by COVID-19 (family income 43.8%, and food access 49.6%, respectively). Over half of participants had experienced frequent (moderate) to persistent (severe) anxiety about COVID-19 (n = 727; 52.0%) and almost a fifth had experienced stress and discord in the family (n = 727; 18.6%). Two-fifths had also experienced occasional to frequent sleep issues (moderate-severe) (42.2%). Two-thirds of those who deemed medical care access applicable to them (n = 728; 60.2%) experienced a range of issues with accessing health services, from appointments moving to telehealth (mild), delays in appointments or prescriptions (moderate), and lack of access, which had a significant impact on their health (severe) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical characteristics, personality types, and coping strategies of all young people by poor mental health status (n = 641)

| Total | Poor mental health |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 194) | No (n = 447) | |||

| Age mean [SD] | 19.6 [2.8] | 19.2 [2.7] | 19.8 [2.8] | .015 |

| Gender N [%] | ||||

| Female | 628 [78.9] | 161 [83.0] | 344 [77.0] | .004 |

| Male | 159 [20.0] | 27 [13.9] | 100 [22.4] | |

| Other | 9 [1.1] | 6 [3.1] | 3 [.7] | |

| Ethnicity N [%] | ||||

| White/White-British | 485 [75.7] | 147 [75.8] | 338 [75.6] | .564 |

| Black/Black-British | 10 [1.6] | 5 [2.6] | 5 [1.1] | |

| Asian/Asian-British | 85 [13.3] | 25 [12.9] | 60 [13.4] | |

| Other | 61 [9.5] | 17 [8.8] | 44 [9.8] | |

| Relationship statusa N [%] | ||||

| Single, divorced, separated or widowed | 386 [60.6] | 109 [56.1] | 277 [62.5] | .002 |

| In a relationship, married/civil partnership or engaged | 231 [36.0] | 72 [37.1] | 159 [35.9] | |

| It is complicated | 20 [3.1] | 13 [6.7] | 7 [1.6] | |

| Mood, sleep, and optimism mean [SD] | ||||

| PHQ-9 | 9.5 [6.1] | 16.2 [4.8] | 6.6 [3.8] | <.001 |

| PANAS positive affect | 24.2 [7.8] | 21.0 [7.0] | 25.6 [7.8] | <.001 |

| PANAS negative affect | 23.0 [8.3] | 30.0 [7.6] | 20.0 [6.5] | <.001 |

| SCIb | 20.1 [7.6] | 15.2 [7.4] | 22.3 [6.6] | <.001 |

| LOT-Rc | 12.2 [4.9] | 9.3 [4.7] | 13.5 [4.4] | <.001 |

| Self-harm N [%] | ||||

| Reported self-harm before lockdown | 203 [31.7] | 120 [61.9] | 83 [18.6] | <.001 |

| Reported self-harm after lockdown | 69 [10.8] | 69 [35.6] | 0 [0] | <.001 |

| Personality traits mean [SD] | ||||

| Extraversion | 4.3 [1.6] | 3.8 [1.6] | 4.5 [1.6] | <.001 |

| Agreeableness | 4.8 [1.1] | 4.6 [1.1] | 4.9 [1.1] | <.05 |

| Conscientiousness | 5.1 [1.3] | 4.6 [1.5] | 5.3 [1.2] | <.001 |

| Emotional stability | 3.9 [1.6] | 2.8 [1.4] | 4.3 [1.4] | <.001 |

| Open-mindedness | 5.0 [1.1] | 5.0 [1.3] | 5.1 [1.1] | .446 |

| Coping strategy mean [SD] | ||||

| Eating related | 6.7 [1.9] | 6.8 [1.9] | 6.6 [1.9] | .261 |

| Acceptance | 6.1 [1.5] | 5.6 [1.5] | 6.4 [1.4] | <.001 |

| Self-distraction | 6.1 [1.3] | 6.1 [1.4] | 6.1 [1.3] | .919 |

| Positive reframing | 5.0 [1.7] | 4.6 [1.7] | 5.2 [1.6] | <.001 |

| Emotional support | 4.6 [1.7] | 4.5 [1.8] | 4.6 [1.7] | .303 |

| Humour | 4.5 [1.9] | 4.7 [2.0] | 4.4 [1.8] | .115 |

| Planning | 4.4 [1.7] | 4.4 [1.8] | 4.5 [1.7] | .343 |

| Active | 4.4 [1.6] | 4.0 [1.5] | 4.6 [1.5] | <.001 |

| Self-blame | 3.9 [1.7] | 5.2 [1.8] | 3.3 [1.2] | <.001 |

| Instrumental | 3.8 [1.5] | 3.9 [1.6] | 3.8 [1.5] | .927 |

| Venting | 3.8 [1.3] | 4.2 [1.4] | 3.6 [1.3] | <.001 |

| Behaviour disengagement | 3.1 [1.4] | 4.1 [1.6] | 2.7 [1.0] | <.001 |

| Religion | 3.0 [1.7] | 3.0 [1.8] | 2.9 [1.7] | .553 |

| Substance use | 2.7 [1.3] | 3.2 [1.8] | 2.5 [1.0] | <.001 |

| Denial | 2.6 [1.1] | 3.0 [1.4] | 2.4 [1.0] | <.001 |

PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PANAS Positive, and Negative Affect Schedule, LOT-R Life Orientation Test-Revised, SCI Sleep Condition Indicator, SD Standard deviation.

n = 637.

lower score indicates poorer sleep.

lower score indicates less optimism.

A fifth indicated a diagnosis of a mental health condition (n = 796; 20.2%). Diagnoses varied and included major depression, anxiety, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and emotionally unstable personality disorder. No participant indicated bipolar disorder or psychosis. Around two-thirds of these (64.1%) experienced no change to their mental health treatment access (n = 410; 56.4%). One in 10 participants reported that they self-harmed during lockdown (n = 69; 10.8%).

Mental health status

The prevalence of poor mental health (as defined above) was 30.3% (n = 194/641). Gender and relationship status was significantly associated with mental health status (χ2 = 11.155 and χ2 = 12.220, p < .01, respectively) (Table 2). 60.3% of those with poor mental health did not report having a mental health diagnosis. PANAS negative affect mean scores were significantly higher in those with poor mental health (t = −15.817 respectively, p < .001, Table 2). LOT-R and SCI mean scores were also significantly lower in those with poor mental health (t = 10.856 and t = 11.486, respectively, p < .001, Table 2), indicating less optimism and worse sleep.

Personality traits and coping strategies associated with poor mental health

Participants with poor mental health were significantly less likely to have extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability personality traits than those without poor mental health (Table 2). No significant differences were found for open-mindedness personality traits. The most common coping strategy by all was eating-related, followed by acceptance and self-distraction, while the least common were religion, substance use, and denial (Table 2). Participants with poor mental health had significantly lower mean scores on positive reframing (t = 4.095, p < .001) and acceptance (t = 6.201, p < .001). In contrast, participants with poor mental health had significantly higher mean scores on self-blame (t = −13.219, p < .001), substance use (t = −5.195, p < .001), venting (t = −5.880, p < .001), denial (−4.614, p < .001) and behavioral disengagement (−11.922, p < .001). No significant differences were found between those with and without poor mental health on emotional support, humor, planning, instrumental and religion coping strategies.

Multivariable factors of poor mental health status

A multivariable logistic regression was conducted to identify factors associated with poor mental health status during COVID-19 lockdown (Table 3 ). Nonretained variables included positive affect, coping strategies, venting, acceptance, positive reframing, active and personality traits, agreeableness, emotional stability, and extraversion. LOT-R contributed to the model on its own but was removed once added to other retained variables because it did not improve the model fit. There were 14 retained variables, including behavioral disengagement, self-blame, SCI, and PANAS negative affect. Age and self-blame also significantly contributed to the model. The remaining retained variables were added to the model but were not significant. The full model was significant (χ2(14), = 318.884, p < .001) and explained the 85.7% variance in poor mental health status.

Table 3.

Summary of multivariable logistic regression showing association of personal characteristics with poor mental health

| Logistic coefficient | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black/Black-British ethnicity | 1.305 | 3.688 | .54–25.40 | .185 |

| “It is complicated” relationship status | .835 | 2.305 | .71–7.48 | .165 |

| Behaviour disengagement coping strategy | .380 | 1.462 | 1.22–1.76 | <.001 |

| Female | .281 | 1.324 | .68–2.58 | .411 |

| Self-blame coping strategy | .268 | 1.307 | 1.10–1.55 | .002 |

| In a relationship | .254 | 1.290 | .76–2.18 | .342 |

| Substance misuse coping strategy | .192 | 1.211 | 1.02–1.44 | .031 |

| PANAS negative affect | .103 | 1.109 | 1.07–1.15 | <.001 |

| Gender identified as “other” | −.037 | .963 | .17–5.55 | .967 |

| SCI | −.088 | .915 | .88–.95 | <.001 |

| Age | −.118 | .889 | .81–.97 | .012 |

| Consciousness personality trait | −.200 | .819 | .69–.98 | .025 |

| Other ethnicity | −.349 | .706 | .32–1.56 | .388 |

| Asian/Asian-British ethnicity | −.361 | .697 | .35–1.38 | .301 |

PANAS Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, SCI Sleep Condition Indicator.

Qualitative results

Participant characteristics

Eighteen participants completed interviews. Most were females in a relationship and socially distancing (Appendix C). A third of participants were from BAME communities (33.3%). Everyone had access to an outside space, but types of access varied. While 11.1% had a diagnosed mental health condition, 29.4% had self-harmed before lockdown. This is similar to the study’s survey results. Overall, the scores for the group indicated mild depression and did not indicate insomnia disorder, indicated by a score of ≤16. The majority of interviews were recorded on Microsoft Teams. One interview was conducted via the chat text function, at the request of the participant.

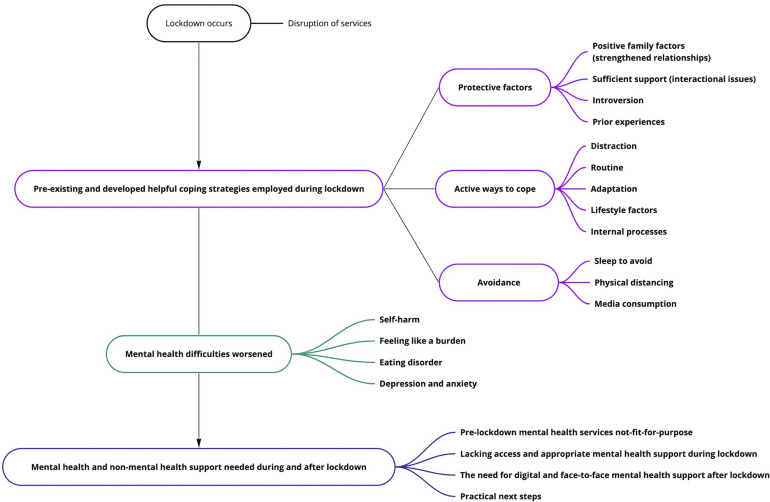

Themes

There were three main themes (Figure 1 ). The themes link together the influence of (1) pre-existing and developed helpful coping strategies employed during the lockdown, (2) mental health difficulties worsened during the lockdown, and (3) mental health and nonmental health support needed during and after lockdown.

Figure 1.

Co-produced thematic map.

Pre-existing and developed helpful coping strategies employed during the lockdown

Protective factors

The majority of participants indicated that protective factors, whether internal or external, were crucial in helping them to cope during the lockdown. Key internal factors included having an introverted personality and having developed implementable coping strategies before COVID-19. For example, some participants discussed having prior experience of isolation, and therefore, they did not mind staying at home. Similarly, having prior experience of long-distance relationships that relied on digital means to communicate or being at home a lot helped several participants cope during the lockdown.

“When I'm not working, I'm at home with my mom anyways, so I'm used to being at home with her… Maybe that's why I've been OK with it, cause… it's not so weird for me to be at home that long I guess” Interviewee ID 626, Female

External factors included existing or increased sufficient support from a family member, partner or friends, which was described by many participants as vital to coping during COVID-19. Quality of connection was more important than the physical proximity of young people’s friendship groups. However, knowing that lockdown was everyone’s problem meant that “everyone was in the same boat” and further enabled connection with others and reassurance. In contrast, some participants reported issues interacting with friends and family. For example, some reported feeling annoyed with other’s “disregard for the rules”, particularly with those with whom they shared living space.

One participant with a mental health diagnosis expressed concern that she was overburdening her family with her worries now that she was back to living at home. Despite this, she was able to manage by utilizing coping strategies she had learned previously.

Active ways to cope

All participants indicated that maintaining a daily routine was a fundamental coping strategy during the lockdown. Routine often involved trying to stick to a schedule they had before the lockdown, such as getting up, exercising, and having meals at the same time each day. Some had continued doing schoolwork or working during the day. However, those who did not have school or work indicated that their mental health had worsened. Key lifestyle factors reported to help participants cope included having a good quality sleep, being outside, drinking alcohol, eating well, and getting regular exercise. Similarly, others reported using more emotion-focused coping such as controlled breathing, mindfulness, and meditation. The majority of participants indicated that they distracted themselves in various ways to help keep themselves busy and take their minds off the pandemic in various ways. For example, some participants played music, podcasts, or watched Netflix while others were creative or cleaned. Other participants iterated on the importance of positive reframing to cope and being spontaneous, optimistic, and joking with friends or family.

“Positive reappraisal was something I did quite a lot right at the start… trying to find like things I can do that I couldn't do before so I can see the good side of everything… I feel like this is a good time for kind of re-examining myself and really trying to focus on what I want to accomplish about things” Interviewee ID 335, Male

Avoidance

All participants indicated they adhered to social distancing rules, and therefore, often avoided visiting people, friends, and places to cope with the lockdown. Some also avoided consuming news coverage of COVID-19 and social media because of the negative impact of content concerning death, frustration with the government, and evidence of friends disregarding lockdown rules. One participant had previous experience in using sleep to cope with stressful situations and used it to avoid dealing with the lockdown.

“This really did start just when sort of when lockdown happened, like about two weeks into lockdown, for some reason, since about then till now, I just had such huge problems, like mainly with falling asleep”, Interviewee ID 188, Female

Mental health difficulties worsened

The majority of participants indicated their mental health had worsened since lockdown. For example, nearly all participants reported feeling anxiety, worry, and uncertainty related to lockdown, going outside, and the future. However, this mostly reduced as the lockdown continued. Most participants without a mental health diagnosis also reported having experienced signs of depression, including feeling lonely, hopelessness, and low mood. Some participants reported feeling like a burden on their family members, having reduced self-worth and experienced suicidal thoughts and feelings. Several participants, regardless of diagnosis, described the times when they had self-harmed during the lockdown but had not done so previously. Reasons for self-harm were described as largely being due to feelings of distress, feeling like a burden on family, and anxiety related to lockdown. For example, one participant described how she had relapsed because of the lockdown and was cutting herself to relax.

“I've struggled… with it during lockdown…it has made things harder to carry on. You know when I'm feeling low, but for me it's definitely just a kind of soothing thing almost like it relaxes me a little bit. Makes me feel a little bit less, uhm. Yeah. Little bit less crazy, ironically” Interviewee ID 845, Female

Additionally, in one participant with a mental health diagnosis, eating disorder symptoms of controlling eating and exercise were reported to have been exacerbated by the lockdown. In contrast, some participants indicated that their mood had improved during the lockdown. This seemed to be related to being less busy, and therefore, having more time to relax, reflect and gain perspective on life. Practically, some participants indicated their relationships had significantly improved. For example, some participants reported that they had experienced fewer arguments in the family, and some indicated they valued their intimate relationships more.

Mental health and nonmental health support needed during and after lockdown

Prelockdown mental health services not fit for purpose

Participants who had accessed mental health services previously reported that these had substantial problems prior to lockdown, were in disarray, and could not cope with the number of young people needing mental health support. Some expressed the need for shorter waiting lists, more financial investment, and to make mental health a policy and funding priority. Several participants reported no compassion and understanding from clinicians they had engaged with. One participant explained how she was just told to stop self-harming rather than exploring the reasons why she was self-harming. However, this did not help her stop self-harming.

Lacking access and appropriate mental health support during the lockdown

Pre-existing mental health support not being fit for purpose was reported to have a direct impact on the lack of support during the lockdown. For example, the two participants needing NHS mental health support stated they were unhappy with the amount they had received. One expressed concern that she received tokenistic support and was only contacted by phone to check she had not harmed herself. Moreover, most participants indicated that peer support was a key alternative in the absence of access to traditional services during and also after the lockdown. For example, some participants said people should support their friends with their mental health and share coping strategies.

“Since lockdown I have reached out to my university's mental health service but have not had a response, I suppose due to high demand” Interviewee ID 590, Female

Practical next steps

The majority of participants indicated a need for guided self-management for nonmental health concerns. Practical concerns included transitioning into employment and education, and financial issues. For example, some participants suggested there was a need for digital video consultation on the next life steps for young people after lockdown. Some participants also indicated that they needed support from schools to help with the transition back to “normality” and to specifically acknowledge the possibility of young people struggling during this period.

“You're in primary school, [then] in high school, no one really talks about mental health, and when they do, it's too late. You need [it] from day dot, taught about how to be resilient and how to know when you're not feeling great” Interviewee 845, Female

The need for digital and face-to-face mental health support after lockdown

In contrast, some indicated they had their life plans in place (e.g., starting university) but that they needed mental health support. The need for nondigital school-based mental health support was highlighted by some. Some participants indicated that the mental health nurses in schools have a vital role in destigmatizing mental health so that people felt they could ask for help. Similarly, some participants also suggested that education regarding mental health, in general, was needed to reduce stigma and self-manage their own mental health. Moreover, participants indicated there was a need for digital mental health support, particularly when traditional face-to-face support was limited during the lockdown. This was despite a preference for face-to-face support. For example, the use of video consultations was recommended so that faces could still be seen, maintaining connection and also helping to reduce loneliness.

“I get to hear their voices and also their expression… It makes me feel less lonely during this lockdown” Interviewee 505, Female

Discussion

Main findings

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first coproduced mixed-methods examination of the mental health and coping strategies in young people during the lockdown in the UK. Just under a third had poor mental health. Over half of respondents experienced frequent/persistent worries about COVID-19. Around 10% of the young people had self-harmed since the lockdown and all these had poor mental health. While eating-related, acceptance, and distraction coping strategies were the most commonly employed, they were not significantly associated with poor mental health. Indeed, distraction in a nonpandemic situation is usually understood as a dysfunctional coping strategy, but in our study, it was not associated with poor mental health. Factors significantly associated with poor mental health were behavioral disengagement, self-blame, and substance use coping strategies, negative affect, sleep problems, and conscientiousness personality traits.

Unsurprisingly, issues with appropriate and effective mental health care before lockdown negatively influenced the care young people received during the lockdown. However, most had effectively used at least one, or a combination, of the following: having a routine, good quality sleep, exercise, getting outside, meditation/mindfulness, and being distracted. Education in relation to mental health self-care was reported to be needed. Additionally, participants described a need for help in transitioning out of the lockdown and into education and employment or to new ventures. Increased mental health access and support were identified as particularly salient during and after the lockdown for young people. Video consultations, mental health school nurses, and peer support were identified as interventions that could be introduced.

There are many preprints and ongoing studies examining the psychological impact of COVID-19 in the UK [7,8]; however, peer-reviewed publications are minimal to date. The point-prevalence of poor mental health in our study was higher than in a representative population of the same age pre-COVID (30.3% vs. 17.3%) and during COVID-19 (16.0%; aged 18–24) [11,35]. However, we also included 16–18-year-olds and used different proxy measures of poor mental health status, which may explain the disparity. In contrast, self-harm frequency was lower than a pre-COVID comparison (10.8% vs. 17.5%; aged 16–24) [35]. Young people identifying as Black/Black-British ethnicity in our study had the highest increased odds of experiencing poor mental health. Interestingly, some studies examining young people’s mental health during COVID-19 have not reported ethnicity. While our finding is not significant, it is noteworthy and should be considered for future support implementation. Indeed, Smith and colleagues highlight the need to respond to the mental health needs of people from BAME communities during COVID-19 [36]. Being female was also associated with poor mental health status, in line with previous studies. However, overall, these demographic factors had wide confidence intervals and should, therefore, be taken with caution. Mental health has worsened in the UK [37] and outside the UK [9,38]. This is in line with our qualitative analysis. However, UK longitudinal studies specifically examining young people are needed to verify these results. Our next step is to report on the mental health and coping strategies of young people over time.

Strengths and limitations

The coproduced mixed methods design is a key strength of this study. We were able to explain and elaborate on our survey results and explore better ways of supporting young people during and after the first UK COVID-19 lockdown. The high representation of young people from BAME communities in both the survey and interviews is also a key strength and allows for a better understanding of the mental health of this group. However, our sample was mainly women, and we did not collect data on sexuality despite the association with poorer mental health in LGBTQ + groups. It is also a fairly small cross-sectional sample compared to some larger studies that used probability sampling [8]. The online platforms and the opportunistic convenience sampling used in our study means it cannot be generalized easily to the rest of young people in the UK and may have excluded some groups (e.g., those who were not online). Our sampling strategy also included contacting mental health charities and community groups that work with young people, which may mean that our sample is skewed toward young people who have experienced mental health difficulties. The cross-sectional nature of the survey also means that causation cannot be established.

Implications

Our findings have several implications. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown has worsened young people’s mental health, and it can be expected that young people will continue to experience difficulties such as heightened anxiety at times due to future uncertainty. However, quality connections with family, partner and friends, and self-implemented active coping strategies can help mitigate this. Indeed, self-management has been shown to have positive effects on mental health symptoms in those with existing mental health difficulties [39]. Moreover, these coping strategies can be shared with other young people struggling with lockdowns. Notably, the adaptiveness of coping strategies may differ under lockdown conditions. NHS mental health services will always be needed, but access is limited, and other forms of support can sometimes be more appropriate. Therefore, peer support could be considered an excellent addition and has been encouraged by others [40]. Online peer support may also be a good alternative considering the lockdown restrictions, its effectiveness and popularity with young people, and the current restrictions in place [41]. In addition to mental health support, there is a need for practical support during and transitioning out of the lockdown and into the “new normal.” Schools and universities are well placed to facilitate simple and cheap digital sessions that cover essential advice, evidence-based coping strategies, life skills, and signposting for employability, educational and financial concerns, and overcome the lockdown barriers to face-to-face support.

Acknowledgments

NIHR Patient Safety Translational Research Centre program grant (Ref: PSTRC-2016-004) and Institute of Global Health Innovation. We are also grateful for support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) program for North West London and the Imperial NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). We would also like to thank all the young people who helped prioritize the research focus. We would also like to thank all the participants for taking the time of their lives to take part in our study. Special thanks also go to Nikita Rathod, Justine Alford, Lily Roberts, and other staff at IGHI and Imperial College London in helping with participant recruitment and advertising the study as widely as they could. We would also like to thank Anthony Thomas for his help in designing the REDCap database.

Author contributions: LD drafted the manuscript, to which all authors contributed extensively. All authors reviewed and approved the final version. LD, ALJ, CC, JJ, LC, CK, DN, MS, PA codesigned the study. LD led quantitative data collection and designed and managed the quantitative data collection database throughout the data collection process. LD, CC, CK, JJ jointly led the qualitative data collection and qualitative data analysis. LD, ALJ, CC, JJ, LC, CK, DN, MS, PA contributed to data interpretation. AB advised on quantitative data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: PA received funding from Dr Foster Ltd (a wholly-owned subsidiary of Telstra Health). AB received funding from Dr Foster Ltd and Medtronic. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.009.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html Available at:

- 2.Public Health England . Public Health England; London: 2020. Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes E.A., O’Connor R.C., Perry V.H., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office for National Statistics Suicides in the UK: 2018 registrations. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2018registrations Available at:

- 6.Patel V., Flisher A.J., Hetrick S., et al. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369:1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre COVID-19 and mental health studies register. https://www.maudsleybrc.nihr.ac.uk/research/covid-19-studies-project-search/ Available at:

- 8.COVID MINDS Network COVID-MINDS. https://www.covidminds.org/ Available at:

- 9.Jean M., Twenge T.E.J. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76:2170–2182. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith L., Jacob L., Yakkundi A., et al. Correlates of symptoms of anxiety and depression and mental wellbeing associated with COVID-19: A cross-sectional study of UK-based respondents. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.YoungMinds Mental health impact of the Covid-19 coronavirus on young people with mental health needs. https://youngminds.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/coronavirus-having-major-impact-on-young-people-with-mental-health-needs-new-survey/ Available at:

- 13.Widnall E., Winstone L., Mars B., et al. NIHR School for Public Health Research; Newcastle-upon_Tyne, United Kingdom: 2020. Young people ’ s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Initial findings from a secondary school survey study in South west England. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanley B., Tarpey M. Involving the public in COVID-19 research: A guest blog by Bec Hanley and Maryrose Tarpey. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/about-us/news-updates/involving-public-covid-19-research-guest-blog-bec-hanley-and-maryrose-tarpey/ Available at:

- 15.Richards T., Scowcroft H. Patient and public involvement in covid-19 policy making. BMJ. 2020;370:m2575. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratneswaren A. The I in COVID: The importance of community and patient involvement in COVID-19 research. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20:e120–e122. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Lancet Psychiatry Asking the right questions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:647. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spirito A., Donaldson D. Suicide and suicide Attempts during Adolescence. Compr Clin Psychol. 1998:463–485. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creswell J., Clark V. Sage Publications Ltd.; London, UK: 2007. Designing and conducting mixed methods research - John W. Creswell, Vicki L. Plano Clark - Google Books. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denzin N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J Mix Methods Res. 2012;6:80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewa L.H., Lawrence-Jones A., Crandell C., et al. Reflections, impact and recommendations of a co-produced qualitative study with young people who have experience of mental health difficulties. Health Expect. 2020 doi: 10.1111/hex.13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewa L., Lavelle M., Pickles K., et al. Young adults’ perceptions of using wearables, social media and other technologies to detect worsening mental health: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hickey G., Brearley S., Coldham T., et al. National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) INVOLVE; Southampton: 2018. Guidance on co-producing a research project. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espie C., Kyle S., Hames P., et al. The sleep condition indicator: A clinical screening tool to evaluate insomnia disorder. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004183. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson D., Clark L.A., Tellegen A. Development and Validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiorri C, Bracco F, Piccinno T, et al. Psychometric Properties of a revised version of the ten item personality Inventory. Eur J Psychol Assess 31, 2015, 109–119.

- 28.Gosling S.D., Rentfrow P.J., Swann W.B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J Res Pers. 2003;37:504–528. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheier M.F., Carver C.S. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Heal Psychol. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheier M.F., Carver C.S., Bridges M.W. Distinguishing optimism from Neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-Mastery, and self-Esteem): A Reevaluation of the life Orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nock M.K., Holmberg E.B., Photos V.I., et al. Self-injurious thoughts and Behaviors interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an Adolescent sample. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufman J., Stoddard J. Coronavirus impact scale. https://dr2.nlm.nih.gov/search/?q=21816 Available at:

- 33.Carver C.S. You want to measure coping but Your Protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McManus S., Bebbington P., Jenkins R., et al. NHS Digital; Leeds: 2016. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric Morbidity survey 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith K., Bhui K., Cipriani A. COVID-19, mental health and ethnic minorities. Evid Based Ment Health. 2020;23:89–90. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2020-300174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce M., Hope H., Ford T., et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S., Wang Y., Xue J., et al. The impact of COVID-19 Epidemic Declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active Weibo users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lean M., Fornells-Ambrojo M., Milton A., et al. Self-management interventions for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;214:260–268. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naslund J., Aschbrenner K., Marsch L., et al. The future of mental health care: Peer-To-peer support and social media. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:113–122. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ali K., Farrer L., Gulliver A., et al. Online peer-to-peer support for young people with mental health problems: A systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2015;2:e19. doi: 10.2196/mental.4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.