Western medicine has begun a reckoning with its inconvenient pasts, from dethroning medical heroes to an increasing awareness of how doctors have treated colonized and enslaved populations. A statue of the “father of modern gynecology,” J. Marion Sims, was removed from New York City’s Central Park in 2018 after protestors in “blood-spattered” hospital gowns objected to glorifying a doctor who experimented on enslaved Black women (Figure 1).1 In 2020, the release of video recorded by Joyce Echaquan, an Indigenous woman who died in a Quebec hospital as nurses repeated racial slurs, sparked street protests. Medical students at the University of Pittsburgh are rewriting their Hippocratic oath to include a commitment to social justice. Medical journals, professional medical associations and public health authorities in several North American cities have declared structural racism a public health crisis.

Figure 1:

A woman stands beside the empty pedestal where a statue of J. Marion Sims was removed from Central Park, New York City, in 2018. Photo used with permission from Getty Images.

Image copyright Getty Images./Spencer Platt. No standalone file use permitted.

These are not isolated fragments but elements of a single story — the past, present and future of race and colonialism in medicine. Complex histories like Sims’ have been edited to create a hero’s narrative, an attempt to “keep the good and leave the bad,” but unmooring medicine from its problematic past does not conquer racism. Instead, racism goes underground, to continue invisibly in medical structures and cause misdiagnosis, poor patient care, dysfunction, abuse and public backlash.

What can be done? Histories reveal the why and how, the mechanics of racism in health policy, medical research, diagnosis, training, clinical spaces, patient experiences, professionalism and institutions. Sims matters precisely because he was considered a successful doctor, one celebrated by his colleagues and lionized by the medical establishment. The actual and unexpurgated historical Sims shows how “good” doctors can do bad things, and it unearths the specific ways that individual doctors, culture, institutions, knowledge, society and power intersect to perpetuate racism. Medicine can use history to help achieve structural competency, an interdisciplinary medical education approach that applies an understanding of structural inequities and social determinants to clinical care.2

How colonialism shapes medical knowledge

European empires were global capitalist systems for the extraction of resources, created and maintained through violence. Empires generate racism because empires need racism to exist. Race theory validated colonial conquest and naturalized white imperial rule.3 Consider Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” which exhorts the “white races” to govern the non-Western world, “your new-caught sullen peoples, half devil and half child.” Empire shaped medicine — Sims could “borrow” 3 enslaved women for experimentation because empire made some human beings into property. Gynecology was useful to slaveholders who wanted to breed human slaves and thus increase their capital and wealth.4

Science served colonialism primarily by codifying race, by “discovering” it in physical and social reality — in biometrics, pathology, physiology, architecture, philology, history, ethnography and sociology. 5 Enshrined in edifices of data and perpetuated by institutions, racism has continued in medicine long after formal empire and slavery have ended.

Consider, for example, “exotic syphilis,” a theory begun in French colonial Algeria by Dr. Emile-Louis Bertherand (d. 1890). Bertherand argued that Muslim Algerians were constitutionally different from Frenchmen. Islam, polygamy and sexual perversion were alleged to have “starved the brain” to create a uniquely “Muslim Arab” physiognomy —hypersexual, with feeble intelligence, weakened by hereditary syphilis.6 Bertherand had no proof to support his claims, but French doctors adopted them unquestioningly for the conquest of Morocco. From 1912, the French protectorate’s medical establishment confidently and repeatedly pronounced Moroccans 80%–100% syphilitic.6

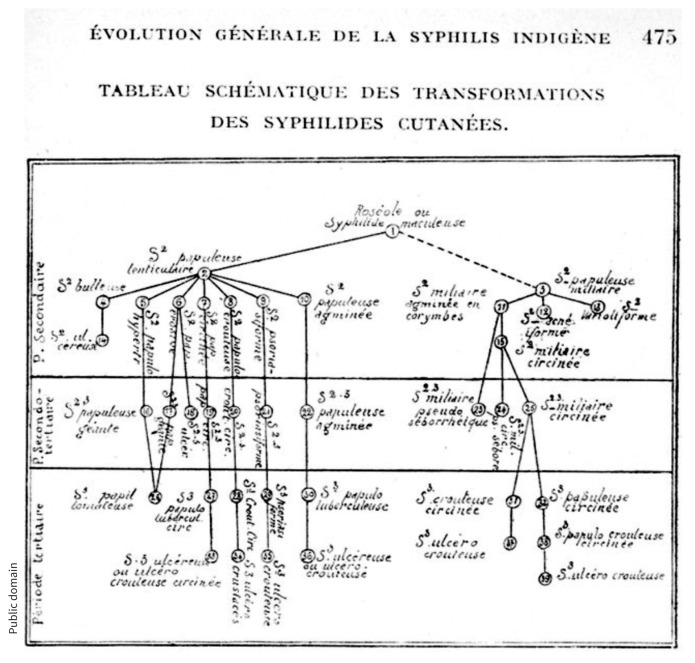

How could doctors proclaim an epidemic that did not exist? Physicians of the French protectorate collected data through racist assumptions, extrapolated from tiny samples of prostitutes, diagnosed syphilis by sight and used non-specific serological tools like the Wassermann test. But it was syphilologist Dr. Georges Lacapère who invented “Arab syphilis” from 8000 patient case histories at his Fès clinic — assembling unrelated skin lesions, birth defects and tumours into a pathology atlas — for his prize-winning 1923 book, La syphilis arabe: Algérie, Maroc, Tunisie (Figure 2).6

Figure 2:

Lacapère’s schematic of the evolution of “Arab syphilis.” From Georges Lacapère, La syphilis arabe: Maroc, Algérie, Tunisie (Paris: Octave Doin; 1923).

Image courtesy of Public domain

“Exotic syphilis” expanded to become a global theory through international experts and academic conferences. According to this idea, the “races of colour” developed cutaneous syphilis because they had underdeveloped brains and primitive nervous systems; neurological symptoms afflicted only the “civilized and culturally evolved.”6 The notorious Tuskeegee syphilis study (1932–1972) attempted to test this hypothesis in a sample of African American people in the United States and see whether they would develop “exotic syphilis.” From 1932–1972, the U.S. public health service in Alabama recruited poor African American men from rural areas and secretly denied them treatment for decades to observe the ravages of their untreated syphilis.7

The history of “exotic syphilis” illustrates how medicine can perpetuate racist ideas in pathology, research, conferences, journals, institutions, grants and medical careers. The Tuskeegee study was finally stopped in 1972 by public outcry after a new research assistant, a Jewish immigrant from Poland, leaked information to a reporter at the Associated Press. This illustrates that individual actors are not powerless against structural forces — cycles of racism can be disrupted even by individuals.

Racism can continue long after formal empire has ended, in systemic inequities of housing, economics, culture, law and medicine. These social factors create marginalization for racialized people and render them vulnerable to medical experimentation and exploitation.8

How colonialism shapes public health and health care

As Southern Chiefs’ Organization Grand Chief Jerry Daniels remarked, “While shocking to many in Canada and the rest of the world, [Joyce Echaquan’s] video confirms what First Nations people and communities across the country have been reporting for years.”9 Indigenous and Black communities are clear that the experiences of Joyce Echaquan, John River and others are not aberrations.10,11 Public health care originated in nation-states, where the medical system served a national citizenry. However, with empire, a state without accountability is the health care provider for a subject human population with few legal rights. We can identify colonial legacies in present-day health care, for colonial empire warps health systems in consistent and structural ways.

In a colonial health care system, race is the basis for resource allocation, thus two populations are served — one the valued colonizer and the other a less valued, colonized population. The principal purpose of colonial health care is to promote the viability and reproduction of the colonizer. 12 The colonized will receive health care when the colonial state wishes to win their loyalty, protect a colonized labour force or prevent anticolonial revolution. Race-based medicine produced segregated hospitals — well-funded, modern hospitals for colonizers and underfunded, inferior hospitals for the colonized.13

Indigenous medicines were usually rejected and Western medicine was often used to inculcate values of empire, an ideological strategy called “civilizing” or “assimilation.” Indigenous health care was often delegated to Christian churches to shift expense from government to private funds, especially in the British empire. Doctors who spoke out against systemic abuses often found themselves reassigned or fired.14

Toward decolonizing medicine

The medical past provides a roadmap for the operational why and how of racism in current medical structures. Specific histories of physicians illustrate ways that diversity can help bring structural change to medicine. Dr. Anderson Abbott, the first Black physician in Canada, returned to the US to fight slavery in the Union army and serve as chief surgeon of the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Emily Stowe, the first woman physician in Canada, also founded the Canadian women’s suffrage movement and a Canadian women’s medical college. Both Abbott and Stowe engaged in the larger struggles for civil rights because they understood their own challenges within the larger systems of injustice that affected all women and all Black people. Physician–community alliances made medical and social progress possible. Black communities founded Black medical schools and Black hospitals like the Taborian Hospital in Mississippi. Women organized to help found women’s medical colleges and maternity hospitals, which in turn provided women physicians with postgraduate hospital training.

Diversity disrupts entrenched thinking. Dr. Rebecca Crumpler, the first Black woman physician in the United States, innovated “the heart conversation,” empathic communication with Black patients whose high rates of tuberculosis went undiagnosed by white public health doctors.15 Women doctors challenged misogynist medical theories like the intellectual inferiority of women (Madeleine Pelletier, 1874–1939) and the disease entity “hysteria” (Mary Putnam Jacobi, 1842–1906). Collective organizing matters; medical residents no longer work 40-hour shifts because women doctors organized for work–life balance. Diverse groups of physicians today are reframing medical issues in marginalized communities, 16 identifying hidden barriers, organizing for change and modelling new ways of being a doctor.

Uncensored, warts-and-all medical history provides a resource to orient us in the present, to identify racism as a systemic problem in contemporary medicine and to craft interventions for an antiracist future. In 2019, the Canadian Medical Association published an equity and diversity policy,17 but issued no policy for antiracism. As George Dei wrote in 1996, racism will not disappear on its own; we must actively dismantle it through “an action-oriented strategy for institutional systemic change.”18 History provides the why and how; it is time for institutions, physicians and communities to decolonize medicine in Canada.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Ellen Amster reports a grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council and speaker fees from Rutgers University Center for Historical Analysis, outside the submitted work.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Owens DC. Medical bondage: race, gender, and the origins of American gynecology.Atlanta: University of Georgia Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhabha H. Of mimicry and man: the ambivalence of colonial discourse. October 1984;28:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paugh K. The politics of reproduction: race, medicine and fertility in the age of abolition.Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Said E. Orientalism.New York: Vintage; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amster E. The syphilitic Arab? A search for civilization in disease etiology, native prostitution, and French colonial medicine. In: Lorcin P, Shepherd T, editors. French Mediterraneans. Lincoln (NB): University of Nebraska Press; 2016: 320–46. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones JH. Bad blood: the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.New York: The Free Press; 1981,1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Washington HA. Medical apartheid: the dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present.New York: Anchor Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowrie M, Geraldine K. Malone Joyce Echaquan’s death highlights systemic racism in health care, experts say [video]. CTV News 2020. Oct. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCallum MJL. Structures of indifference: an Indigenous life and death in a Canadian city. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser SL, Gaulin D, Fraser WD. Dissecting systemic racism: policies, practices, and epistemologies creating racialized systems of care for Indigenous peoples. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amster EJ. Medicine and the saints: science, Islam, and the colonial encounter in Morocco, 1877–1956. Austin: University of Texas Press; 2013: 110–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lux M. Separate beds: a history of Indian hospitals in Canada, 1920s–1980s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hay T, Blackstock C, Kirlew M. Dr. Peter Bryce (1853–1952): whistleblower on residential schools. CMAJ 2020;192:E223–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.More ES. Restoring the balance: women physicians and the profession of medicine, 1850–1995. Cambridge (UK): Harvard University Press; 1999:95–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reducing disparities in diabetic amputations [blog]. NIH Diabetes Discoveries and Practices. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2021. Apr. 21. Available: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/professionals/diabetes-discoveries-practice/reducing-disparities-in-diabetic-amputations (accessed 2022 Mar. 31). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Equity and diversity in medicine. Ottawa: The Canadian Medical Association; 2019. Dec. 7. Available: https://www.cma.ca/physician-wellness-hub/resources/equity-diversity/policy-for-promoting-equity-diversity-in-medicine (accessed 2022 Mar. 31). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sefa Dei GJ. Critical perspectives in antiracism: an introduction. Can Rev Sociol 1996;33:247–67. [Google Scholar]