Abstract

Injections with hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers for facial rejuvenation and soft-tissue augmentation are among the most popular aesthetic procedures worldwide. Many HA fillers are available with unique manufacturing processes and distinct in vitro physicochemical and rheologic properties, which result in important differences in the fillers' clinical performance. The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the properties most widely used to characterize HA fillers and to report their rheologic and physicochemical values obtained using standardized methodology to allow scientifically based comparisons. Understanding rheologic and physicochemical properties will guide clinicians in aligning HA characteristics to the facial area being treated for optimal clinical performance.

Keywords: aesthetics, hyaluronic acid fillers, elastic modulus, rheology

Hyaluronic acid (HA) filler injections for facial rejuvenation and soft-tissue augmentation were the second most popular nonsurgical aesthetic procedures in 2019, with 4.3 million procedures performed worldwide, an increase of 16% from the previous year. 1 Features that may contribute to the popularity of HA filler treatments include their biocompatibility and degradability, overall safety and tolerability, high hydrophilicity, ease of administration, minimal recovery time, immediate results, and low incidence of immunologic reactions. 2 3 4 5 6 HA fillers used in aesthetic indications typically consist of chemically crosslinked HA molecules, resulting in a hydrogel that is less susceptible to enzymatic degradation (i.e., has longer duration) and has improved rheologic properties compared with uncrosslinked HA. 7 8 Variations in manufacturing processes, such as degree of crosslinking, crosslinking conditions (temperature, pH), molecular weight of the starting HA, and post-crosslinking modifications (sieving/homogenization, addition of lidocaine, etc.), can impact filler characteristics. 3 9 10 11 12

Understanding the range of HA filler products from the standpoint of their rheologic and physicochemical characteristics can provide an initial framework for predicting treatment outcomes 13 and assist clinicians in selecting the appropriate attributes for each treated facial area. 11 14 Rheologic and physicochemical properties of HA fillers impact performance characteristics (i.e., lift capacity, resistance to deformation, and tissue integration), which, together with injection technique (i.e., injection plane, location, volume) and the interaction of the filler with the surrounding tissue, may affect clinical outcomes. 15

There are different methodologies for measuring and characterizing the rheologic and physicochemical properties of crosslinked HA fillers; the use of standardized in vitro assays can provide the basis for understanding how different fillers may perform under different situations. 7 16 This article presents data on rheologic and physicochemical characteristics of HA fillers using consistent methodology to allow a scientifically based comparison. Guidance on appropriately aligning HA rheologic and physicochemical characteristics to the facial area being treated follows, with the goal of helping clinicians make informed decisions about HA filler selection.

Overview of the Rheologic and Physicochemical Characteristics of HA Fillers

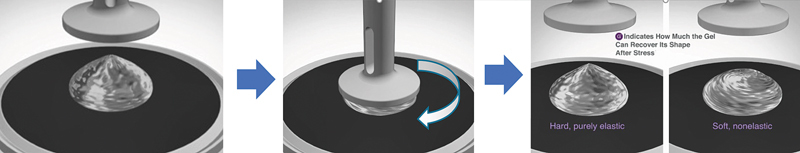

HA fillers are viscoelastic materials—i.e., they demonstrate both viscous and elastic properties when subjected to shear deformation. 17 Once injected, HA fillers encounter various forces, such as relative movement (shear) between tissue layers (skin, muscles, fat pads, bone), gravity, and/or compression (by overlying tissues or external pressure). 15 Therefore, assessing the behavior of fillers in response to mechanical stress provides clinically relevant information. 13 Rheology, the study of the way a material deforms and reacts under mechanical stress, allows for this assessment. 18 Four rheologic parameters may be used as the primary measures of a gel's viscoelastic properties: G* (a measure of the overall viscoelastic properties), G′ (a measure of the elastic properties), G″ (a measure of the viscous properties), and tan δ (tan delta, a measure of the ratio of the elastic to viscous properties). 7 17 19 20 Using a rheometer, a twisting force is applied to a gel between two plates to measure these parameters 12 ( Fig. 1 ). The tests are performed using a range of frequencies (e.g., 0.1 to 10 Hz) to simulate variability in the degree of dynamic movement across the face. 12 21 22 As with any analytical technique, results will depend on not only the material (i.e., the filler) but also the instrument used for testing and on the experimental conditions (frequency, amplitude, plate geometry, temperature, etc.). Comparing results from rheologic studies that have used different methodologies is challenging because it requires good scientific comprehension and understanding of limitations; thus, care should be taken in making comparisons across different studies. 16 23

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of a rheometer in oscillation mode. The gel is placed between two plates of defined geometry to assess elasticity (solid behavior) quantified by the elastic modulus, or G′, indicating how much the gel can recover its shape after shear stress. The same experiment also measures G″, the viscous modulus. From these measured parameters, G* and tan delta (δ) can be calculated. 11 17 20

Definitions of the most common rheologic and physicochemical properties used to characterize HA fillers are provided in Table 1 7 11 14 17 20 24 and discussed in greater depth below.

Table 1. Rheologic and physicochemical characteristics of HA fillers measured in vitro.

| Parameters | Definitions | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Complex modulus 11 17 20 | G*, or hardness, measures overall viscoelastic properties of a gel. |

For most HA fillers, G* and G' are similar. The value of G* is derived from the formula

.

.

|

| Elastic modulus 11 17 20 | G′, or elasticity, measures the elastic properties of the gel and its ability to recover its shape after shearing stress is removed. | The most common descriptor for HA fillers, G′ is a measure of the strength (firmness). G′ is influenced by the degree of crosslinking and total HA concentration. |

| Viscous modulus 11 14 17 20 | G″, or loss modulus, measures the viscous properties of the gel and its inability to recover its shape. | HA fillers tend to have low G″. |

| Tan delta (δ) 11 17 20 24 | Tan δ is the ratio between the viscous and the elastic components of the HA gel (G″/G′). | Tan δ characterizes whether the gel is more viscous or more elastic (proportion of G″ to G′). Tan δ is usually low in crosslinked HA fillers, meaning that the elastic behavior under low shear stress is dominant over the viscous behavior. |

| Gel cohesion (cohesivity) 11 17 | Cohesivity measures the resistance to vertical compression/stretching. | This property characterizes how a filler behaves as a gel deposit once it is injected and subjected to forces. Gel cohesion is influenced by HA concentration and the crosslinking and sizing/homogenization of the gel. |

| Water uptake 7 11 | Water uptake, or swelling factor, measures the ability of the gel to swell from water uptake. | Water uptake/swelling factor helps anticipate the initial volumization of an implanted gel. It is influenced by the degree of crosslinking and HA concentration. |

| HA concentration 7 11 | This parameter is the total amount of HA found in the filler, expressed as mg/mL, and includes insoluble and soluble HA. | Insoluble HA is the crosslinked HA and the foundation for the effectiveness and durability of the filler. Soluble HA is the noncross-linked and rapidly degradable form of HA (from HA fragments, or usually added for facilitating extrusion). HA concentration impacts all the parameters. |

Abbreviation: HA, hyaluronic acid.

Complex Modulus (G*)

Complex modulus, or G*, measures the overall viscoelastic properties of a gel and is commonly referred to as “hardness.”

17

G* describes the global response of the filler to deformation, takes into account both the elastic component (G′) and the viscous component (G″), and is derived through the equation

.

17

20

This parameter represents the strength of the material (hardness) or the total energy needed to deform it.

25

.

17

20

This parameter represents the strength of the material (hardness) or the total energy needed to deform it.

25

Elastic Modulus (G′)

Elastic modulus (also known as storage modulus), or G′, measures the elastic properties of the gel, specifically the ability of the gel to regain its original shape after deformation. 25 26 G′ represents the energy stored in the material and recovered once the shearing stress is removed. 17 Elastic modulus is the most common descriptor for HA fillers and represents a solid-like behavior that reestablishes the shape of the filler once injected. 20 22 Fillers with low to medium elasticity (G′) are characterized as soft fillers. 27 Most HA fillers available are predominantly elastic, with nearly equal G′ and G* values. 20

Many manufacturers use the degree of crosslinking and gel concentration to influence the softness or firmness of their fillers. 7 Increasing the degree of crosslinking will increase the elasticity of the gel, thus elevating G′. 7 As the distance between crosslinks decreases, the overall matrix strengthens and makes the gel stiffer or firmer (higher G′). 7 Decreasing the number of crosslinks lengthens the distance between the links of the HA molecules, allowing for less force to deform the gel and leading to a softer and less elastic filler (lower G′). 7 27 In HA fillers manufactured with the same technology and with the same degree of crosslinking, increasing the HA concentration will lead to an increased G′, resulting in a firmer filler. 7

G′ is traditionally viewed as an indicator of the lift capacity of a filler. 13 17 23 27 28 29 30 31 However, there is not always a linear relationship between G′ and lift. 13 Among fillers with similar composition or crosslinking technology, G′ has a positive correlation to overall lift capacity, but when comparing fillers with different compositions or different crosslinking technologies, lift does not always correlate with increasing G′ because many other parameters also influence performance. 13

Viscous Modulus (G″)

Viscous modulus, or G″, measures the viscous properties of the gel and represents the energy lost during deformation. 26 Hence, it is also known as the “loss modulus.” 26 G″ describes the inability of the filler to recover its shape after the sheer stress is removed, and it is linked to the liquid behavior of the gel, allowing the gel to deform and flow to some extent during injection. 11 17 20 HA fillers tend to have low G″. 14 For any HA filler to be effective, it needs to be viscoelastic, i.e., viscous enough to be injected and initially molded, but elastic enough to resist shear deformation forces and provide a durable correction once implanted into soft tissue. 11 17 20 It is important to note that G″ is distinct from viscosity, which relates to the flow of the filler during injection and does not impact clinical performance. 8 17

Tan Delta (tan δ)

Tan δ is the ratio between the viscous (G″) and elastic (G′) components of the HA gel (i.e., tan δ = G″/G′) and evaluates the relative contributions of each property. 11 17 20 Tan δ >1 signifies a mostly viscous filler, whereas tan δ <1 indicates a mostly elastic filler. 18 Most HA crosslinked fillers have tan δ <1 (i.e., G′ > G″). 17 While tan δ allows an understanding of whether the filler is more elastic or more viscous, it is important to note that it does not provide information on the actual magnitudes of G′ and G″. 32

Gel Cohesion (cohesivity)

Gel cohesion (also called cohesivity) represents the adhesion forces within the gel and characterizes how a filler behaves as a gel deposit once injected, which makes cohesivity an important property to consider in the overall behavior of a filler. 17 At the time of injection, HA fillers with lower cohesivity tend to be easier to mold and spread more easily. 17 However, when subjected to the compressive forces of the face, fillers with lower cohesivity do not maintain their shape and projection as well as fillers with higher cohesivity and similar G′. 17 When high compression is applied to a low-cohesivity gel, there is a risk of detachment/separation of gel from the original deposit, which can result in filler migration. 17 When high compression is applied to a high-cohesivity gel, the gel deposit resists this force more easily and retains its original shape. 17 Cohesivity is a function of both HA concentration and degree of crosslinking. 17 Under the same crosslinking technologies, increasing either the HA concentration or the crosslinking degree increases cohesivity. 17

Manufacturers use different methods for determining the cohesivity of HA filler products, and no standardized assay exists. 16 Compression methods, such as the compression force test or the pull-away method, use the rheometer to measure normal force (N) by subjecting the gel to vertical compression (attempting to simulate the compression movements of the face) or positioning the gel between two plates pulled apart at a constant speed. 9 14 17 30 33 34 35 Other cohesivity assays include the drop weight method, wherein an HA gel is pushed through an opening at a constant speed and its weight is determined, and the visual shear-stressed gel method, which is based on physical handling of the gel. 34 35

Water Uptake

Water uptake (or swelling factor) is a measure of the ability of the HA gel to swell from water uptake and is a function of both HA concentration and degree of crosslinking. 7 11 The crosslinking technology used in the manufacture of the filler highly impacts the filler's in vitro swelling rate, and maximum swelling depends on the crosslinking density of the network. 10 As the number of crosslinks increases, the chains are held more tightly together, and their flexibility in moving apart (stretching to accommodate the water) becomes more limited, thus reducing the swelling capacity of the gel. 10 Changes in water uptake mainly occur immediately post-injection and can contribute to the initial volumization. 13

There are different methods for assessing water uptake, 7 34 36 all intended to determine how much water the gel will absorb under optimal conditions. As with other measures, absolute swelling factor values depend on experimental conditions, but a range of values may be observed among fillers. 34 It is important to note that in vitro water uptake assessments represent the maximum ability of the gel to absorb water (unconstrained water uptake), and once HA fillers are injected in the face, many other constraints (e.g., composition and water content of surrounding tissues, forces acting on tissues) will limit the fillers' ability to fully expand. 11

HA Concentration (mg/mL)

This measure is the total amount of HA found in the filler, comprising both insoluble crosslinked HA and the soluble HA mostly derived from noncrosslinked HA added to facilitate the passing of the gel through a needle. 7 11 The crosslinking technology determines variables such as HA concentration and degree of crosslinking. 10 Fillers manufactured using the same technology and degree of crosslinking may have increased elasticity (G′) with increased HA gel concentrations, which yield greater molecular entanglements. 7 Assuming consistent degree of crosslinking, initial HA molecular weight, post-crosslinking modifications, and other conditions such as increased HA concentration will result in greater water uptake and longer duration of the filler. 37

Rheologic and Physicochemical Measurements of HA Filler Products

The previously described rheologic and physicochemical characteristics are important for developing an understanding of HA filler characteristics that allows selection of fillers that may be suited for each indication and facial area. However, for values to be meaningful for direct comparison, studies of the rheologic and physicochemical properties must be conducted using consistent methodology.

To obtain information on the rheologic and physicochemical properties of HA filler products across manufacturers, different products were tested for G′, G″, tan δ, cohesivity, and water uptake using the standardized methods described by Hee and colleagues. 13 Briefly, fillers were tested using a rheometer at 5 Hz with 0.8% strain; resistance to compression to assess cohesivity was measured using maximum normal force at 0.8 mm/min for 2 minutes; and water uptake was measured by dyeing any buffer that was not taken up by the filler gel and calculating maximum absorption ratio as the percentage difference between initial and final gel percentage. 13 Table 2 reports the rheologic and physicochemical values of HA filler products obtained using this methodology. 13

Table 2. Rheologic and physicochemical characteristics of HA fillers (data from Hee et al 13 and data on file, Allergan Aesthetics, an AbbVie company). All products were tested under the same conditions using the same methodologies 13 .

| Filler product name a | HA (mg/mL) | G' 5Hz (Pa) | G'' 5Hz (Pa) | Tan δ | Cohesivity/Fn (gmf) | Maximum water uptake, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belotero Soft+ | 20 | 40 | 42 | 1.050 | 16 | <100 |

| Belotero Balance+ / Lips Contour | 22.5 | 128 | 82 | 0.641 | 69 | 664 |

| Belotero Intense+ / Lips Shape | 25.5 | 255 | 110 | 0.431 | 115 | 700 |

| Belotero Volume+ | 26 | 438 | 103 | 0.235 | 97 | 370 |

| Juvéderm Ultra | 24 | 156 | 68 | 0.436 | 96 | 580 |

| Juvéderm Ultra XC | 24 | 207 | 80 | 0.386 | 96 | 622 |

| Juvéderm Ultra Plus | 24 | 214 | 74 | 0.346 | 116 | 515 |

| Juvéderm Ultra Plus XC | 24 | 263 | 79 | 0.300 | 112 | 454 |

| Juvéderm Ultra 2 | 24 | 188 | 75 | 0.399 | 95 | 574 |

| Juvéderm Ultra 3/Smile | 24 | 238 | 71 | 0.298 | 104 | 426 |

| Juvéderm Ultra 4 | 24 | 164 | 66 | 0.402 | 105 | 614 |

| Juvéderm Volite | 12 | 166 | 30 | 0.181 | 12 | <100 |

| Juvéderm Volbella with lidocaine | 15 | 271 | 39 | 0.144 | 19 | 133 |

| Juvéderm Volift with lidocaine | 17.5 | 340 | 46 | 0.135 | 30 | 184 |

| Juvéderm Voluma with lidocaine | 20 | 398 | 41 | 0.103 | 40 | 227 |

| Juvéderm Volux | 25 | 665 | 49 | 0.074 | 93 | 253 |

| Restylane Fynesse | 20 | 134 | 58 | 0.433 | 30 | 677 |

| Restylane Refyne | 20 | 116 | 50 | 0.431 | 49 | 516 |

| Restylane Kysse | 20 | 236 | 50 | 0.212 | 85 | 373 |

| Restylane Defyne | 20 | 342 | 47 | 0.137 | 60 | 318 |

| Restylane Volyme | 20 | 239 | 50 | 0.209 | 91 | 354 |

| Restylane Vital Light | 12 | 84 | 49 | 0.583 | 12 | <100 |

| Restylane Vital | 20 | 667 | 172 | 0.258 | 27 | <100 |

| Restylane | 20 | 864 | 185 | 0.214 | 29 | <100 |

| Restylane Lyps | 20 | 976 | 166 | 0.170 | 31 | <100 |

| Restylane Lyft | 20 | 977 | 198 | 0.203 | 32 | <100 |

| Restylane SubQ | 20 | 1055 | 123 | 0.117 | 42 | <100 |

| Teosyal Puresense Redensity II | 15 | 114 | 43 | 0.372 | 16 | 239 |

| Teosyal Puresense First Lines | 20 | 105 | 44 | 0.419 | 18 | 250 |

| Teosyal Puresense Kiss | 25 | 314 | 66 | 0.209 | 74 | 380 |

| Teosyal Puresense Deep Lines | 25 | 301 | 64 | 0.214 | 82 | 300 |

| Teosyal Puresense Ultra Deep | 25 | 348 | 54 | 0.155 | 87 | 250 |

| Teosyal RHA1 | 15 | 133 | 54 | 0.406 | 22 | 260 |

| Teosyal RHA2 | 23 | 319 | 99 | 0.310 | 77 | 420 |

| Teosyal RHA3 | 23 | 264 | 67 | 0.254 | 109 | 427 |

| Teosyal RHA4 | 23 | 346 | 62 | 0.179 | 115 | 366 |

Abbreviation: HA, hyaluronic acid.

All product trade names are the property of the respective owners (Belotero products, Merz Aesthetics; Juvéderm products, Allergan Aesthetics, an AbbVie company; Restylane products, Galderma Laboratories, LP; Teosyal products, Teoxane Laboratories). All products tested, except Juvéderm Ultra and Juvéderm Ultra Plus, contained lidocaine.

Selecting the Appropriate HA Filler Based on Its Rheologic and Physicochemical Characteristics

Considerations Pertaining to HA Filler Characteristics and Specific Facial Regions

As described, rheologic and physicochemical properties have implications for the clinical performance of HA fillers, and their alignment to the facial area being treated can help optimize clinical outcomes. HA fillers are expected to function not only as volumizers in areas that have volume deficit and wrinkles or deep folds, but also to look and feel natural, whether in static or more dynamic areas of the face. 13

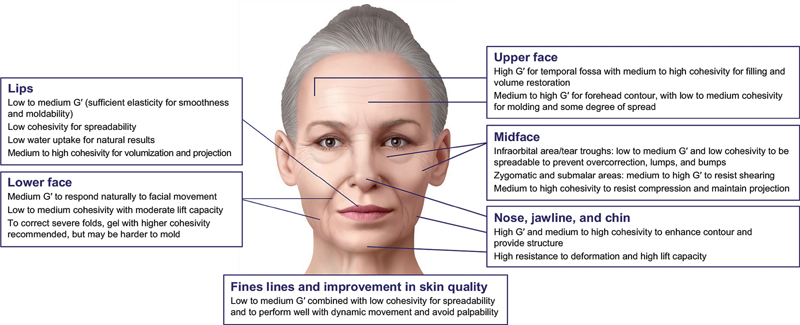

Below are guiding principles for using HA fillers in facial aesthetic correction based on pertinent rheologic and physicochemical properties. Fig. 2 summarizes the recommended filler characteristics for each facial region.

Fig. 2.

HA filler characteristics recommended in facial aesthetics. HA, hyaluronic acid.

Upper Face

In areas of the upper face where filling and volume restoration are required, as in the temporal fossa, 14 38 39 40 41 the HA filler should have high elasticity or resistance to deformation (G′) and medium to high cohesivity. To address forehead contour, the filler chosen should have a medium to high G′ and a low to medium cohesivity, 42 which would allow for molding and some degree of spread upon injection.

Midface

The infraorbital area is characterized by very thin tissue overlying bone with skin that is only a few millimeters thick. Therefore, a filler for this area should have low to medium elasticity or resistance to deformation (G′) and a low cohesivity for ease of spreadability and to prevent overcorrection, lumps, and bumps. 12 17 20 Because the aesthetics of the periorbital area are highly sensitive to minimal volume changes, a filler with low water uptake should be used to minimize the risk of swelling and puffiness under the eyes. 40 43

The zygomatic and submalar areas are subject to dynamic contraction forces of the lip and cheek elevators. Therefore, the fillers used in these areas need to have a medium to high elastic modulus (G′) to resist shearing and medium to high cohesivity to withstand compression forces of the overlying tissue and maintain projection. 44 45

This degree of cohesivity is essential to ensure minimal separation and avoid product displacement that may occur after repetitive contraction of the overlying musculature. 46 To provide projection, the fillers to be used in the midface should have a high lift capacity. Several HA filler products with the described rheologic and physicochemical properties have demonstrated effectiveness for the treatment of the midface. 14

Lower Face

The lower face is an area characterized by a high degree of dynamic movement; loss of volume and structural support in this area, resulting in marionette lines, nasolabial folds, or accordion lines, requires consideration of distinct rheologic characteristics, such as medium elasticity (G′) and low to medium cohesivity, 17 47 48 with a moderate lift capacity. The ideal filler for this region would need to be easily moldable, have low projection, be nonpalpable, and integrate well with facial movement, as it will be subjected mostly to shearing and mild compression forces. However, to correct severe folds, a filler with higher cohesivity is recommended, 14 17 47 48 although it could be harder to mold after injection. 17

Lips

To enhance the lips, fillers are usually described as soft, i.e., having low to medium elasticity (G′) and low to medium cohesivity, since the challenge in this area is to avoid edges and bumps. Also, a low swelling factor is usually recommended to avoid unnatural-looking results. 11 49 For a smoothing effect, lip fillers require lower lift capacity and easy moldability. 50 51 Increasing the cohesivity from low to medium or even to high will contribute to projection and volumization. 9 50 52 There are several HA fillers with the appropriate combination of elasticity, cohesivity, softness, and water uptake that have been shown to be effective for treating the lips. 14 50 51

Nose, Jawline, and Chin

The chin, jaw, and nasal dorsum are areas of low shear stress but are characterized by high compression, with taut skin and muscle over bony structures. Thus, the filler of choice to enhance contouring and provide structure should have high elasticity (G′) and medium to high cohesivity 42 and provide high lift capacity and resistance to deformation. Such a filler would minimize lateral spreading and maintain a sharp vertical projection over time. Different products with the appropriate balance of these rheologic properties have demonstrated effectiveness for these regions in clinical trials. 14 42

Fine Lines and Improvement of Skin Quality Attributes

HA filler products can improve superficial wrinkles by filling in shallow lines, thus smoothing the skin and leading to an appearance of improved skin quality. Fillers with low HA concentration that exhibit low to medium elasticity (G′) combined with low cohesivity are best suited to treat superficial fine lines, such as those in the periorbital and perioral areas. 14 53 54 As mentioned earlier, HA fillers with low cohesivity are generally easier to mold and have increased spread in tissues. As these fillers are usually injected superficially, they require low lift capacity, low resistance to deformation, and good tissue integration. This type of filler will integrate well with the surrounding tissue, will perform well with dynamic movement, and will be less likely to result in visible edges and bumps or palpabality. 14

Conclusion

The face is a dynamic and complex structure, and therefore the requirements for each area of the face should be taken into consideration when choosing a filler. This overview of the rheologic and physicochemical properties of HA fillers, together with a summary of rheologic and physicochemical values for multiple products measured using the same methodologies, will provide a valuable resource for clinicians. Aligning the rheologic and physicochemical properties of HA fillers to the facial area being treated, along with using the appropriate injection technique, can help clinicians select the right product to achieve optimal aesthetic results.

Conflict of Interest A. Virno, M. Musumeci, A. Bernardin, C. de la Guardia, and M. Silberberg are employees of AbbVie and may own AbbVie Stock.

Note

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided to the authors by Mayuri Kerr, PhD of Allergan Aesthetics and Regina Kelly of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Allergan Aesthetics. All authors met the ICMJE authorship criteria. No honoraria were paid for authorship.

References

- 1.International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery ISAPS international survey on aesthetic/cosmetic procedures performed in 2019 2020. Accessed October 14, 2021 at:https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Global-Survey-2019.pdf

- 2.Humphrey S, Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Clinical experience with 11,460 mL of a 20-mg/mL, smooth, highly cohesive, viscous hyaluronic acid filler. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(09):1060–1067. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philipp-Dormston W G, Bergfeld D, Sommer B M. Consensus statement on prevention and management of adverse effects following rejuvenation procedures with hyaluronic acid-based fillers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(07):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snozzi P, van Loghem J AJ. Complication management following rejuvenation procedures with hyaluronic acid fillers—an algorithm-based approach. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(12):e2061. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matarasso S L. Understanding and using hyaluronic acid. Aesthet Surg J. 2004;24(04):361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salwowska N M, Bebenek K A, Żądło D A, Wcisło-Dziadecka D L. Physiochemical properties and application of hyaluronic acid: a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15(04):520–526. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kablik J, Monheit G D, Yu L, Chang G, Gershkovich J. Comparative physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35 01:302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacos J T, Dayan S H. Superficial dermal fillers with hyaluronic acid. Facial Plast Surg. 2019;35(03):219–223. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1688797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faivre J, Gallet M, Tremblais E, Trévidic P, Bourdon F. Advanced concepts in rheology for the evaluation of hyaluronic acid-based soft tissue fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47(05):e159–e167. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edsman K, Nord L I, Ohrlund A, Lärkner H, Kenne A H.Gel properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers Dermatol Surg 201238(7 Pt 2):1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagien S, Bertucci V, von Grote E, Mashburn J H. Rheologic and physicochemical properties used to differentiate injectable hyaluronic acid filler products. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(04):707e–720e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundaram H, Cassuto D.Biophysical characteristics of hyaluronic acid soft-tissue fillers and their relevance to aesthetic applications Plast Reconstr Surg 2013132(4, suppl 2):5S–21S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hee C K, Shumate G T, Narurkar V, Bernardin A, Messina D J. Rheological properties and in vivo performance characteristics of soft tissue fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41 01:S373–S381. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapoor K M, Saputra D I, Porter C E. Treating aging changes of facial anatomical layers with hyaluronic acid fillers. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1105–1118. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S294812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaud T. Rheology of hyaluronic acid and dynamic facial rejuvenation: topographical specificities. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(05):736–743. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edsman K L, Wiebensjö A M, Risberg A M, Öhrlund J A. Is there a method that can measure cohesivity? Cohesion by sensory evaluation compared with other test methods. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41 01:S365–S372. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierre S, Liew S, Bernardin A. Basics of dermal filler rheology. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41 01:S120–S126. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heitmiller K, Ring C, Saedi N. Rheologic properties of soft tissue fillers and implications for clinical use. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(01):28–34. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldman M P, Few J, Binauld S, Nuñez I, Hee C K, Bernardin A. Evaluation of physicochemical properties following syringe-to-syringe mixing of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(12):1606–1612. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorenc Z P, Öhrlund Å, Edsman K. Factors affecting the rheological measurement of hyaluronic acid gel fillers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(09):876–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micheels P, Besse S, Sarazin D, Obamba M. Hyaluronic acid gel based on CPM ® technology with and without lidocaine: is there a difference? . J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(01):36–44. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zerbinati N, Esposito C, Cipolla G. Chemical and mechanical characterization of hyaluronic acid hydrogel cross-linked with polyethylene glycol and its use in dermatology. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2020;33(04):e13747. doi: 10.1111/dth.13747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundaram H, Voigts B, Beer K, Meland M. Comparison of the rheological properties of viscosity and elasticity in two categories of soft tissue fillers: calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36 03:1859–1865. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falcone S J, Berg R A. Temporary polysaccharide dermal fillers: a model for persistence based on physical properties. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(08):1238–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee W, Hwang S G, Oh W, Kim C Y, Lee J L, Yang E J. Practical guidelines for hyaluronic acid soft-tissue filler use in facial rejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(01):41–49. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falcone S J, Doerfler A M, Berg R A.Novel synthetic dermal fillers based on sodium carboxymethylcellulose: comparison with crosslinked hyaluronic acid-based dermal fillers Dermatol Surg 20073302S136–S143., discussion S143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lundgren B, Sandkvist U, Bordier N, Gauthier B. Using a new photo scale to compare product integration of different hyaluronan-based fillers after injection in human ex vivo skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(09):982–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gold M. The science and art of hyaluronic acid dermal filler use in esthetic applications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(04):301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2009.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dugaret A S, Bertino B, Gauthier B. An innovative method to quantitate tissue integration of hyaluronic acid-based dermal fillers. Skin Res Technol. 2018;24(03):423–431. doi: 10.1111/srt.12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stocks D, Sundaram H, Michaels J, Durrani M J, Wortzman M S, Nelson D B. Rheological evaluation of the physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(09):974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carruthers J, Cohen S R, Joseph J H, Narins R S, Rubin M. The science and art of dermal fillers for soft-tissue augmentation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(04):335–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.La Gatta A, Schiraldi C, Zaccaria G, Cassuto D. Hyaluronan dermal fillers: efforts towards a wider biophysical characterization and the correlation of the biophysical parameters to the clinical outcome. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:87–97. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S220227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundaram H, Rohrich R J, Liew S. Cohesivity of hyaluronic acid fillers: development and clinical implications of a novel assay, pilot validation with a five-point grading scale, and evaluation of six U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(04):678–686. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edsman K LM, Öhrlund Å. Cohesion of hyaluronic acid fillers: correlation between cohesion and other physicochemical properties. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(04):557–562. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho S Y, Park J W, An H. Physical properties of a novel small-particle hyaluronic acid filler: In vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(03):347–354. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baek J, Fan Y, Jeong S H. Facile strategy involving low-temperature chemical cross-linking to enhance the physical and biological properties of hyaluronic acid hydrogel. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;202:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tezel A, Fredrickson G H. The science of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10(01):35–42. doi: 10.1080/14764170701774901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumann L S, Weisberg E M, Mayans M, Arcuri E. Open label study evaluating efficacy, safety, and effects on perception of age after injectable 20 mg/mL hyaluronic acid gel for volumization of facial temples. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(01):67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wollina U, Goldman A. Correction of tear trough deformity by hyaluronic acid soft tissue filler placement inferior to the lateral orbital thickening. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;34(05):e15045. doi: 10.1111/dth.15045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niforos F, Acquilla R, Ogilvie P. A prospective, open-label study of hyaluronic acid-based filler with lidocaine (VYC-15L) treatment for the correction of infraorbital skin depressions. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(10):1271–1280. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hevia O, Cohen B H, Howell D J. Safety and efficacy of a cohesive polydensified matrix hyaluronic acid for the correction of infraorbital hollow: an observational study with results at 40 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13(09):1030–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertossi D, Lanaro L, Dell'Acqua I, Albanese M, Malchiodi L, Nocini P F. Injectable profiloplasty: forehead, nose, lips, and chin filler treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(04):976–984. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharad J. Dermal fillers for the treatment of tear trough deformity: a review of anatomy, treatment techniques, and their outcomes. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5(04):229–238. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.104910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones D, Murphy D K. Volumizing hyaluronic acid filler for midface volume deficit: 2-year results from a pivotal single-blind randomized controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(11):1602–1612. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerscher M, Agsten K, Kravtsov M, Prager W. Effectiveness evaluation of two volumizing hyaluronic acid dermal fillers in a controlled, randomized, double-blind, split-face clinical study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:239–247. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S135441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson A J, Taglienti A J, Chang C S, Low D W, Percec I. Current applications of facial volumization with fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(05):872e–889e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monheit G, Beer K, Hardas B. Safety and effectiveness of the hyaluronic acid dermal filler VYC-17.5L for nasolabial folds: results of a randomized, controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(05):670–678. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monheit G, Kaufman-Janette J, Joseph J H, Shamban A, Dover J S, Smith S. Efficacy and safety of two resilient hyaluronic acid fillers in the treatment of moderate-to-severe nasolabial folds: a 64-week, prospective, multicenter, controlled, randomized, double-blinded, and within-subject study. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(12):1521–1529. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eccleston D, Murphy D K. Juvéderm(®) Volbella™ in the perioral area: a 12-month prospective, multicenter, open-label study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2012;5:167–172. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S35800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geronemus R G, Bank D E, Hardas B, Shamban A, Weichman B M, Murphy D K. Safety and effectiveness of VYC-15L, a hyaluronic acid filler for lip and perioral enhancement: one-year results from a randomized, controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(03):396–404. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer T C, Sattler G, Gauglitz G G. Hyaluron filler containing lidocaine on a CPM basis for lip augmentation: reports from practical experience. Facial Plast Surg. 2016;32(03):283–288. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wende F J, Gohil S, Nord L I, Helander Kenne A, Sandström C. 1D NMR methods for determination of degree of cross-linking and BDDE substitution positions in HA hydrogels. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:1525–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niforos F, Ogilvie P, Cavallini M. VYC-12 injectable gel is safe and effective for improvement of facial skin topography: a prospective study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:791–798. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S216222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Black J M, Gross T M, Murcia C L, Jones D H. Cohesive polydensified matrix hyaluronic acid for the treatment of etched-in fine facial lines: a 6-month, open-label clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(07):1002–1011. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]