Abstract

The study critically examines how students in Mainland China and Hong Kong conceive overseas studies plans against the COVID-19 crisis. Amongst the 2739 respondents, 84 % showed no interest to study abroad after the pandemic. For those respondents who will continue to pursue further degrees abroad, Asian regions and countries, specifically Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan, are listed in the top five, apart from the US and the UK. The pandemic has not only significantly decreased international student mobility but is also shifting the mobility flow of international students. This article also discusses the policy implications, particularly reflecting on how the current global health crisis would intensify social and economic inequalities across different higher education systems.

Keywords: Studying abroad, Transnational higher education, COVID-19 pandemic, Quality education, Student mobility

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, which began in early 2020, has dramatically affected higher education development in various aspects, including the shift of face-to-face teaching to online teaching and learning, the cancellation of physical events and activities and the formation of a ‘new normality’ in higher education (Tesar, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought many challenges to higher education in terms of teaching, learning, research collaborations and institutional governance. Moreover, this pandemic brings about an excellent opportunity for various stakeholders to re-think and even re-design higher education with an effective risk-management plan to increase the sustainability and resilience of this sector in the future. This crisis forces higher education stakeholders to reconsider the role of information and communication technologies (ICT), specifically reviewing the effectivity of online learning in higher education. Although online learning has been treated as a remedy for higher education problems (e.g. rising tuition costs), students and instructors have expressed many negative concerns regarding learning effectiveness and interactions during the pandemic (Herman, 2020; Xiong, Mok, & Jiang, 2020).

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic is remarkable in international higher education, particularly student mobility (Altbach & de Wit, 2020; Mok, 2020a). Owing to the travel restrictions and campus closure, many students changed or cancelled their plan of studying abroad. Hence, higher education institutions (HEIs) from major destination countries, such as the US, the UK and Australia, have anticipated a considerable decrease in incoming international students for the coming semester. For instance, from the survey conducted by the Institute of International Education, approximately 90 % of US colleges and universities have anticipated a decrease in international student enrolment, and 30 % of HEIs indicated a substantial decrease in the academic year 2020–2021 (Martel, 2020). A recent study published by the British Council in April 2020 shows that 39 % of Chinese students, as the largest source of international students in the UK, are unsure about cancelling their study plans (Durnin, 2020). Similarly, the Australian HEIs will face a loss of approximately 150,000 Chinese in the coming school year (Mercado, 2020).

As a primary source of international students to the several destination countries, Mainland China sent out more than 710,000 students in 2019; amongst which, 73 % (518,300) were in the higher education level (New Oriental, 2020). However, with the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese students cancelled or changed their plans of studying abroad for safety reasons and travel restrictions. The Chinese government also announced some notifications, alerting new students not to visit specific destination countries (e.g. Australia) for safety reasons (China’s Ministry of Education, 2020). Against this particular circumstance, some HEIs in the East Asian region have attempted to capture this problem as an opportunity to attract Mainland China students. These HEIs adopted different policies to attract those students who have plans to study abroad. For example, the University of Hong Kong announced its Presidential PhD Scholarship with generous funding to attract students who have received offers from top universities but cannot make the trip due to the pandemic (The University of Hong Kong, 2020).

The present research is set out against the context outlined above to examine how students in Hong Kong and Mainland China respond to the global health crisis resulting from the COVID-19 when planning for overseas learning. The research team adopted the survey instrument and successfully collected 2739 responses of university students in Mainland China and Hong Kong on their studying abroad expectations after the pandemic. To collect data, two specific questions were designed and inserted to the two research projects of the research team using survey questionnaires to examine respondents’ studying abroad expectations. Two questions asked survey participants to indicate if they were still interested in studying abroad after the pandemic. If so, what were the five countries/regions they wanted to go the most? Therefore, the research questions of this study were articulated as below.

-

iAre Mainland China and Hong Kong university students still interested in studying abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

iiWhat are the top countries for Mainland China and Hong Kong university students to study abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

i

This micro-level study on students’ perspectives of studying abroad can contribute to the investigation on the effect of the pandemic on international higher education and student mobility at this particular time. The empirical evidence in this study can also contribute to the studies on the macro-level issues in terms of the COVID-19 pandemic and international higher education, such as international student recruitment policies, institutional management and international collaborations.

2. Literature review

2.1. International higher education and student mobility under the COVID-19 pandemic

Before the present global health crisis, growing debates have emerged to critically examine the future of internationalisation of education, specifically when people begin to question the value and benefits offered by international education. The COVID-19 pandemic again raises issues of the future of international higher education. Would the COVID-19 adversely affect international education and student mobility? Different groups of global higher education stakeholders realise the profound influences brought by the pandemic on international higher education and, particularly, international student mobility. Apart from HEIs (e.g. Lingnan University, 2020a) and international organisations, such as UNESCO (e.g. Goris, 2020), research organisations and teams have been working on this particular topic, such as the Institute of International Education (Martel, 2020), British Council (Durnin, 2020) and World Education Services (Schulmann, 2020). All these studies forecast a decrease in international students to the major destination countries and a global downturn of international student mobility.

For the specific effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility, Marginson (2020a) argued that the negative effect of the pandemic on student mobility will bring substantial financial challenges to universities and countries that depend on international students’ tuitions. Moreover, the international education sector will turn into a buyers’ market, in which the incoming international students become scarce sources. Considering that the pandemic is unevenly distributed in different countries and regions, the student mobility flows will be different in various regions. For example, East Asian countries with a better situation and pandemic control will become the potential major destinations after this particular period.

The COVID-19 pandemic also changes the weight of each factor affecting students and their families in the decisions and country choices of studying abroad. In particular, the pandemic has prioritised health security and safety in their decision making (Marginson, 2020a). To illustrate, in the survey study of British Council on over 10,000 Chinese students, when asked about the major concerns when conceiving their plans for overseas learning, the majority of the respondents overwhelmingly rated ‘personal safety’ (87 %) and ‘health and well-being’ (79 %) as their major worries (Durnin, 2020). Nevertheless, the international media reported several cases showing that Asian students and residents experience discrimination or even assaults when wearing face masks in the UK, Europe and Australia (e.g. Tan, 2020). Such images would have affected Chinese students’ plans and choices for international education (China’s Ministry of Education, 2020; Mok, 2020a).

Other than the health and safety concerns of international students who cancelled their plan to study abroad during the pandemic, the detrimental policies that have been implemented by some popular destination countries become the obstacles for international student mobility. For example, the US federal government implemented the policy of not issuing student visas to international students if they will take all online courses in the coming fall semester. After the strong resistance from international students and some leading universities in the US (e.g. Harvard, MIT and Carnegie Mellon University), this policy was revoked (Jordan & Hartocollis, 2020). However, this policy has brought many negative impressions to international students who want to study in the US. The policy also amplified the overall negative effects of the pandemic on international higher education.

The adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility have been well recognised. However, some scholars still hold an optimistic view that the international student mobility will remain strong after the pandemic, which is similar to the situations during the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the economic crisis in 2008. In addition, the previous efforts of globalisation and internationalisation of higher education in each country have laid a solid basis for student mobility, including the compatible education systems, integrated credit transfer systems and stimulating policies for students exchange (Mercado, 2020).

2.2. Factors influencing students to study abroad

With the development of globalisation and internationalisation of higher education, the demand of students for higher education has dramatically expanded. In addition, a large proportion of students intend to study abroad, which lead to the flourishing of cross-border higher education on an unprecedented scale. Thus, many scholars have examined the factors that influence students to study overseas (e.g. Austin & Shen, 2016; Kim, Bankart, Jiang, & Brazil, 2018; Oliveira & Soares, 2016).

Hossler and Gallagher (2020) stated that the three-stage model is appropriate for illustrating the process of deciding to study abroad. The three stages refer to choosing to study abroad or stay in their home country, and choosing a destination country for studying abroad and choosing an institution for higher education. Although this process is normal in decision making, some students purposefully choose the HEIs, directly bypassing the destination consideration (Chen, 2007). Most of the literature that analyses the process is affected by ‘push–pull’ theory (Lee, 1966). Generally, push factors are related to some negative aspects of the home countries that force the students to leave and study abroad. On the contrary, the pull factors are associated with the positive aspects of destinations that attract the students to study in other countries (Liu & Zhu, 2019). Push and pull factors attract students and motivate them to study abroad, which explain the determinants that cause outflow (Lee, 2017) and are relevant to the first stage of the three-stage model, whether to study abroad.

Six crucial pull factors influence determinants (Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002). The awareness of the host country is the first factor, which is related to the recognition degree of the destination. The second factor is the level of other referrals during the decision-making process. In particular, the view of parents plays a vital role in the final decision (Bodycott, 2009). The third is the cost issues, including not only the living expenses but also the social cost, such as safety. Lee (2013) stated that the cost issue is perceived as the essential factor that affects the final decision, and safety issue is one of the major concerns (Deviney, Vrba, Mills, & Ball, 2014). Environmental factor, such as climate, is the fourth influencing factor, and the geographic proximity is the fifth factor. The sixth pull factor is the social link related to any familiar person or family living in the destination.

Conversely, the push factors include the lack of high-quality education in domestic countries, difficulty in increasing competitiveness and the political or economic condition pushing students to leave the home country (Liu & Zhu, 2019). Pull and push factors are regarded as the individual variables affecting students’ decision to study abroad (Altbach, 1991). However, using this model to distinguish the factors in the diverse group of students during the decision-making process is difficult (Kim et al., 2018). For example, the motivations of the undergraduates and postgraduates to study abroad are different (Briggs, 2006).

The motivations of an individual for studying abroad have become complex and diverse as students have increasing opportunities to choose their favoured destinations and study fields (Wu, 2014). Human-capital theory has been applied as an alternative approach to illustrate the demands for studying abroad for an in-depth understanding of the factors that influence study abroad and the process of decision making (Findlay, 2011). The three dimensions within human-capital theory are scholastic, social and cultural. Scholastic capital refers to the knowledge attainment generated by the degree course, social capital refers to resources gained from the social network during the overseas study and cultural capital is defined as academic credentials (Bourdieu, 2001). Furthermore, studying abroad presents the instrumentalism from the human capital theory perspective (Fong, 2011), and students consider international higher education as an opportunity to increase the wage premium and gain a high return from higher education investment (Cebolla-Boado, Hu, & Soysal, 2018; Cozart & Rojewski, 2015).

The above review regarding factors affecting students’ motivations for overseas learning provides relevant perspectives for the research team to examine and analyse how students in Mainland China and Hong Kong assess the impact of the COVID-19 on their plans for overseas learning. In addition, Amoah and Mok (2020) examined how international students assess the support for personal health and security offered by their institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. They showed that the majority of respondents across 26 countries/regions report insufficient support from their institutions. Hence, many experienced loneliness and helplessness during the crisis. From this point, under the pandemic, whether the university can provide sufficient support to students’ security and wellbeing will become an increasingly important factor for prospective international students for their decision in studying abroad.

In summary, would the current global health crisis fundamentally change the patterns of international student mobility? More importantly, we ask whether the above review based on the existing literature would be sufficient to analyse the uncertain futures of the internationalisation of higher education and global student mobility against the unprecedented global health crisis which has significantly changed overseas learning and international student mobility.

2.3. Mainland China and Hong Kong students’ considerations of studying abroad

After the higher education expansion in 1999, Mainland China enters the massification stage of higher education, and the competition for admission has intensified (Mok & Wu, 2016). Moreover, the qualification of higher education degrees was devalued in the employment market, which also caused an increase in the unemployment rate. Graduates face the difficulties of securing jobs (Mok, 2016; Mok & Wu, 2016). Therefore, several students seek to study abroad for personal and career development. In Hong Kong, the supply of places for higher education falls short of demand. Gaining admission to Western universities by studying abroad is easier than local institutions (Altbach, 1991). Thus, an increasing number of Hong Kong students choose to study abroad for higher education (Mok, 2017).

Mainland China and Hong Kong students have diversified destinations for studying abroad, mainly in English-speaking countries (Lewis, 2016). The university reputation and ranking are the most significant factors influencing Chinese students’ choice of final destination (Lee, 2017). The US and the UK are the two major destinations owing to their respective universities’ strong reputation (Austin & Shen, 2016; Wu, 2014). Austin and Shen (2016) noted that students choose the US as a destination because employers would tend to recruit the employees returning from the US as they are perceived to have further opportunities to increase creativity and develop critical thinking (Tang, 2014) as opposed to the educational system in China which is criticised for lacking innovation (Chao, Hegarty, Angelidis, & Lu, 2019).

Some of the neighbouring Asian countries and regions are also becoming popular as study destinations in recent years, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan (Lee, 2017; Li & Bray, 2007). Li and Bray (2007) stated that Hong Kong and Macau have a common advantage as places capturing the mix of Eastern and Western cultures, thereby serving as the linkage between Mainland China and other countries. Apart from attracting Mainland students, the unique characteristics of Hong Kong and Macau have also globally attracted a different group of students. As an educational hub, the academic reputation and quality of Hong Kong is another motivation for students to choose it as the destination. However, in Macau, economic income is a pull factor that attracts students to select it as a destination. Moreover, Taiwan is considered one choice for its low-cost and high-quality higher education programmes (Lee, 2017). With the comparative advantage of Hong Kong and Macau, would students from Mainland China prefer going to these places for learning than the popular destinations in Europe, Australia and North America?

3. Research design

This study applied the quantitative method to examine Mainland China and Hong Kong students’ attitudes towards studying abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic. As mentioned above, the two survey questions which informed the two research questions of this study were purposely inserted to two research projects, which used the survey questionnaires as data collection instrument. The survey participants were college and university students in Mainland China and Hong Kong. In May 2020, the research team distributed the questionnaires via online survey systems (Qualtrics and Wenjuanxing) to the above two groups of students. For the Mainland China study, research team adopted the random sampling method to access university students; and for Hong Kong study, the research team applied the snowball sampling method to distribute survey questionnaires with certain monetary compensations.

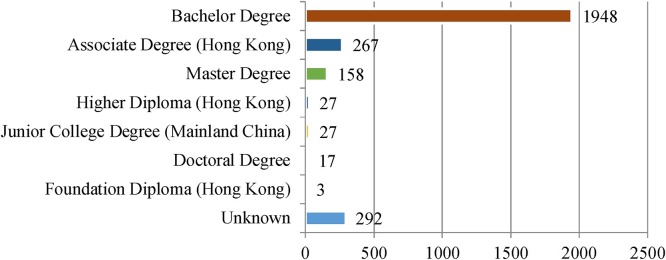

After a few weeks, the research team successfully collected 2739 valid responses from the online survey systems. Amongst all respondents, 1267 (46.3 %) were from Mainland China and 1472 (53.7 %) from Hong Kong. From the demographic details of our respondents, amongst the 2739 respondents, 63 % are females, and 36 % are males. Moreover, 2413 (88.1 %) are between 18 and 25 years old, which is the youngest cohort. Regarding the study levels at universities, 1948 (71.12 %) students are studying in bachelor’s programmes at the time of the survey (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Degree of study undertaken by respondents.

After cleaning and organising the collected data, the research team applied descriptive analysis to examine and demonstrate survey participants’ attitudes towards studying abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic and the top and least choices of study abroad destination countries and regions for those who are still planning to pursue higher degrees out of their countries.

4. Main findings

We found that 2312 (84 %) respondents expressed no interest in studying abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas only 427 (16 %) would consider pursuing further education overseas (Table 1 ). The alarming figure is consistent with that of the Chinese Agency Survey Results conducted by the Beijing Overseas Study Service Association. That is, 73.44 % of the agencies received a lower number of overseas study consultation, and 65.52 % believed that the total number of Chinese students studying abroad would drop this year (Beijing Overseas Study Service Association (BOSSA), 2020).

Table 1.

Number of respondents interested in studying abroad after the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Respondents | Yes (percentage) | No (percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 427 (16 %) | 2312 (84 %) |

| Mainland China | 120 (9%) | 1147 (91 %) |

| Hong Kong | 307 (21 %) | 1165 (79 %) |

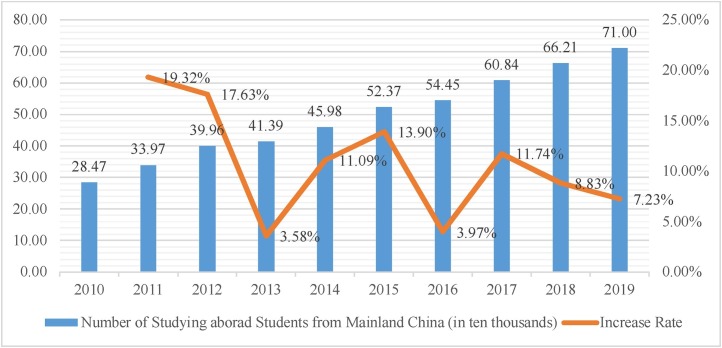

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall number of Mainland students studying abroad consistently increased in the past decade (Fig. 2 ). Despite the rising anti-globalisation and nationalism trend in international higher education (Xiong & Mok, 2020), in 2019, the number reached 710,000, which increased by 8.3 % compared with the 2018 figure (New Oriental, 2020). Moreover, if no pandemic occurred, the number of students in 2020 would reach a new high record according to the trend. Although the number includes all levels of education, as higher-education-degree pursuers take the majority of this group (e.g. 73 % of the 2019 number), this trend can be referred to examine the studying abroad motivations of undergraduate students, who are the primary group of participants in this study.

Fig. 2.

Number of students studying abroad from Mainland China and the increase rate, 2010–2019.

Sources: New Oriental (2020) and Zhiyan Consulting Group (2020).

Therefore, comparing the pre-COVID-19 studying abroad trends with our study findings, we believe that the COVID-19 had an influence on the further study preferences of students undertaking their degrees in Mainland China and Hong Kong. Mainland China and Hong Kong students are less interested in studying abroad when the pandemic is over, which may potentially cast long-term effects on the international higher education sector.

4.1. Young first-degree students

The majority of our respondents are 18 to 25-year-old first-degree seekers who may have little work experience but have several choices (e.g. pursuing a higher degree, gaining some work experience and travelling overseas). Based on the expression mentioned above of the (un)willingness to further study overseas, this large cohort of young and first-degree students may either opt to work or pursue a higher degree back in Mainland China and Hong Kong. Regardless of work or further study, bachelor’s degree graduates in Mainland China and Hong Kong will likely stay to compete for jobs and advanced level degrees in the country. Other vigorous competitions over jobs and studies are anticipated. Hence, we argue that several job vacancies and research study places should be offered to overcome such hardships this year.

4.2. Most popular post-COVID study destinations

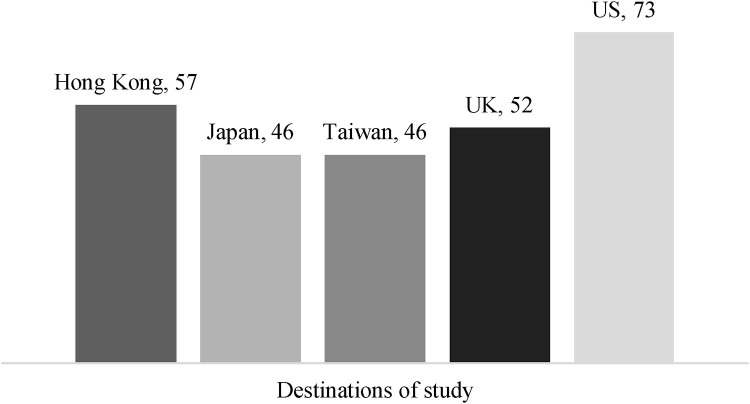

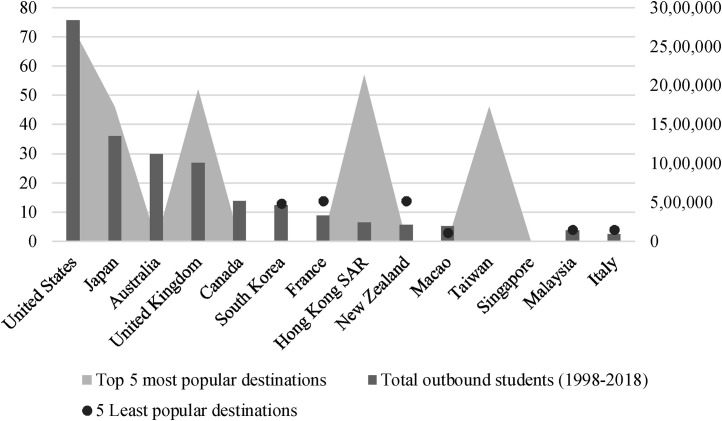

Our survey found that apart from the all-time popularity of studying in the US, other English-speaking nations are witnessing a drop in study inclination, whereas their East Asian counterparts are expecting an increase in the number of Chinese higher education students. Amongst the responses which indicated an interest in studying overseas after the COVID-19 pandemic, the top five most popular study destinations are the US (17.1 %), Hong Kong (13.35 %), the UK (12.18 %), Japan (10.77 %) and Taiwan (10.77 %), as shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Top five most popular study destinations.

Although the UK remains the third most popular option of study destination, the UK was previously the fourth country with the most Chinese higher education students between 1998 and 2018. Compared with the UK, Hong Kong has only been the eighth most popular study destination (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2019) (Table 2 ). However, Hong Kong started to attract more Mainland China students than the UK. Apart from Hong Kong, we observed a recent interest in pursuing further studies in Taiwan, which has never been part of the top 10 study destinations for Mainland China students before.

Table 2.

Top 10 destinations of Mainland China students studying higher education abroad (1998–2018).

| Study destinations | Number of outbound Chinese HEI students |

|---|---|

| US | 2,837,369 |

| Japan | 1,349,463 |

| Australia | 1,118,108 |

| UK | 1,005,794 |

| Canada | 515,700 |

| Republic of Korea | 461,392 |

| France | 330,698 |

| Hong Kong SAR, China | 243,258 |

| New Zealand | 215,740 |

| Macau SAR, China | 197,346 |

Source: UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019).

With Japan remaining as one of the most favourite options, three out of five top destinations are located in East Asia. Moreover, one-third of the respondents who kept their intention to study abroad after the pandemic would stay and study in the region. Hence, we argue that the growing interest to study in Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan is due to their proximity to Mainland China. In times of instability, students may want to stay in neighbouring regions where they can continue entertaining international exposure and easily retreating to the homeland when necessary.

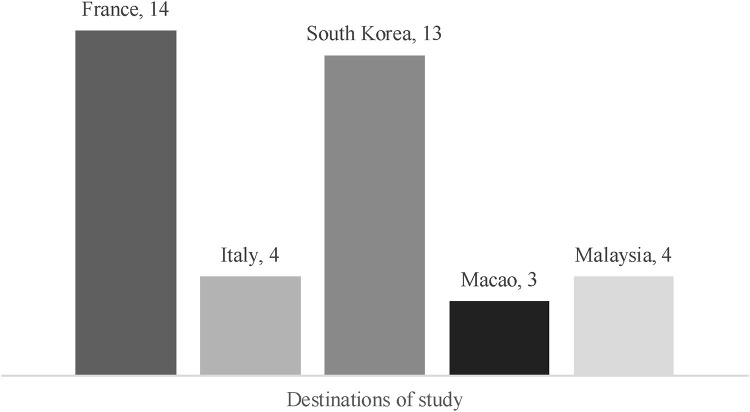

4.3. Least popular post-COVID study destinations

Although the US and the UK remain the most popular study destinations in this study, their Anglophone brothers Australia, Canada and New Zealand no longer top the list as in their previous rankings (Fig. 4 ). Neither Australia nor Canada was voted as the top five popular countries in this study, but New Zealand was ranked the fifth least favourite study option in our survey. However, the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019) (Table 2) shows that Australia, Canada and New Zealand were previously the third, fifth and ninth countries with most Mainland China higher education students from 1998 to 2018, respectively. Further investigations can examine why these three English-speaking nations are not appealing to Mainland China students in this study.

Fig. 4.

Five least popular study destinations.

Table 2 shows that France was formerly the seventh country with most Mainland China higher education students over the last two decades. However, France lost its popularity among our respondents, similar to New Zealand. Only 3.28 % of the respondents would choose to study there. Finally, although some East Asian countries and regions, such as Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan, would recruit more Chinese students than expected, only 3 % of our willing-to-study-abroad respondents chose South Korea and even less than 1 % chose Macau or Malaysia as their upcoming study destinations. Interestingly, South Korea was formerly the sixth country with most Mainland China higher education students in the past 20 years, and Macau was previously the tenth (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2019).

A question is thus raised: Why do some East Asian places become popular but some do not? Fig. 5 contrasts the ratio differences between the total number of Chinese higher education students in the last two decades (blue bars) (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2019) and the five most and five least popular options (yellow dots) in the current survey. We conclude that although the US is as popular as usual, the UK observes a decline in its share for Chinese higher education students. We also conclude that Hong Kong and Taiwan are the ‘winners’ expecting more Mainland China higher education students. Some major reasons accounting for such ‘shift’ is closely related to the better crisis management of governments in Asia when combatting the COVID-19 in terms of preventive measures adopted in enhancing public health. Comparing their actual experiences back home, together with the images broadcast internationally when Asian students were bullied by their western peers because of different public health behaviours, such as wearing face masks in public, growing concerns for personal safety and wellbeing amongst Asian students and parents are becoming common (Mok, 2020b). These findings could offer some useful insights for analysing the findings presented above.

Fig. 5.

Comparison between the total number of Chinese students studying higher education degrees overseas (1998–2018) and the preferences of further study destinations (current survey).

5. Discussion

5.1. International higher education and student mobility amid the pandemic

Research findings of this study on Mainland China and Hong Kong university students’ attitudes towards studying abroad have approved the negative effect brought by the COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility. The barriers for students to pursue their further degrees overseas include travel bans, visa restrictions and campus lockdowns in destination countries, including students and their families’ worries on health and safety. Some practical reasons, such as the delays in English tests, also prevent students from completing the application on time (Mercado, 2020).

The effects of the pandemic on international higher education are manifested in various aspects. As to student mobility, the decrease in international students due to the pandemic will substantially affect overseas HEIs, specifically for those financially depending on the tuitions of international students (2020b, Marginson, 2020a; Tesar, 2020). For example, the UK universities would face an approximately £2.5 billion loss in tuition income in the new academic year (University & College Union, 2020).

Moreover, with international students becoming scarce resources, the competitions for recruiting them will increase in international higher education. Moreover, the rate of recovery from the pandemic and post-pandemic governance will become a significant factor for destination countries to attract international students (Goris, 2020; Marginson, 2020a). This study argues that the domestic job market will become competitive because college graduates will stay to seek jobs instead of studying abroad. The predicted global economic recession will exacerbate this effect after the pandemic (Mercado, 2020).

Some scholars are discussing whether the COVID-19 pandemic will bring an end to the internationalisation of higher education (Heisel, 2020; Helms, 2020; Leask & Green, 2020). In terms of student mobility, based on the present study, although the willingness of Mainland China and Hong Kong students to study in the traditional major destination countries (e.g. the UK, US, Australia) is decreasing, the nearby countries and regions in East Asia would become popular because of the health and safety concerns highlighted above. In our study, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan are on the list of the top five popular destinations. Moreover, some scholars believe that international student mobility will remain strong after the pandemic based on the previous experiences associated with the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the global recession in 2008 (Mercado, 2020).

Furthermore, collaboration in international higher education has been emphasised during the pandemic. In the Webinar hosted by Tohuku University Graduate School of Education (2020) regarding the ‘new normality’ of international higher education in the Asia-Pacific region, the keyword regarding the future is ‘collaboration’. As the anti-globalisation trend and the COVID-19 pandemic have brought many negative effects to international higher education, policymakers, institutional administrators and educators know that individual institutions and countries cannot single-handedly deal with this situation. By contrast, collaborations are highly needed. However, although regaining the collaborations on a global scale will be difficult, the pandemic provides a precious opportunity to enhance regional collaborations.

In short, although the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected the internationalisation of higher education, the trend of regionalisation might become a new trend in international higher education in and after the COVID-19 pandemic. These survey findings and the practices of Hong Kong universities in attracting doctoral students can forecast this trend. We argue that this trend will be feasible in Asia and other regions, such as Europe, where further regionalisation of higher education might be enhanced due to the pandemic.

5.2. Rising trend of East Asian countries and regions

As the research findings present, although the US and the UK remain attractive destinations for the respondents in this study, one-third of them prefer to study in Asian countries and regions. Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan list in the top five popular destinations. Notably, after comparing the most popular destination list of this study with one of the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (2019), we can observe the rising trend of East Asian countries and regions in attracting Mainland China students. This trend has also been identified in recent research on studying abroad of Mainland China students (New Oriental, 2020).

Regarding the reasons for the popularity of East Asian countries and regions for Mainland China and Hong Kong students as prospective places of study, the proximity serves as an essential reason during the COVID-19 and even in the post-COVID era as most Mainland China and Hong Kong students are funded by families for their international education. Their parents hope that they can be near their children for safety reasons. For the push–pull factors of Western countries, the travel restriction and border control of the major destination countries, such as the US and the UK, render the physical entry of Mainland China students to their programmes impossible this year. The worsening pandemic situation and new social movement in the US make decision-making more difficult for Mainland China and Hong Kong students.

For the post-pandemic situation, East Asian countries (e.g. China and Japan) with the Confucian and collective cultural traditions are expected to recover faster than the Western countries (e.g. the US, the UK and Australia) of individualist traditions from the pandemic because of the different governance regimes and cultures (Marginson, 2020b). One point which deserves attention here is the enhanced performance of universities in Asia as revealed by different university league tables. The rise of China, particularly in scientific research, may change the minds of some students in the Mainland to pursue learning and research at institutions that have forged strategic partnerships with their home institutions in Singapore and Hong Kong, specifically when HEIs are good at internationalisation (New Oriental, 2020). Although travelling to an English learning environment is commonly offered by universities in the West, the success of universities in Asia in research and internationalisation could become an attraction for students in Mainland China and Hong Kong when conceiving their overseas learning plans (Mok & Kang, 2020; Mok, Welch & Kang, 2020). Therefore, as international students and their families will increasingly consider health and security, the flow of international student mobility may shift from the traditional East-to-West mode to the East Asia-oriented mode (Marginson, 2020a).

However, the beneficial effects of proximity for East Asian countries are not evenly distributed amongst all East Asian higher education sectors. Based on the research findings, the traditional popular destination countries and regions in East Asia (e.g. Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan) benefit the most in attracting Mainland China students due to its existing strengths (Lee, 2017; Li & Bray, 2007). On the contrary, some other major traditional destination countries and regions, such as South Korea and Macau (UNESCO Institute of Statistics, 2019), lost their popularity in this study, which are listed in the five least popular destinations. A possible reason for the decreasing ranking of South Korea and Macau amid the COVID-19 pandemic might be the influence of Mainland China and Hong Kong students’ ranking-oriented mind-set. When they prefer to studying abroad near their homes (East Asia) due to the pandemic, they want to go to the countries and regions with more top-ranking universities. In this sense, South Korea and Macau with less high-ranking universities lose the attraction to Mainland China and Hong Kong students.

When assessing ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in attracting international students, we should not ignore the negative social and economic consequences when some countries would become winners because they would still have the financial capacity to support young people to study abroad. In analysing the internationalisation of higher education, particularly international student mobility, we should acknowledge that the social and economic inequalities will be further intensified across different parts of the world. Countries which could manage their economic growth during and after the COVID-19 may rebound and continue to support international learning. In addition, for those traditional strong countries in terms of higher education, such as the US and the UK, although they, specifically the US, are greatly affected by the pandemic, they will still retain their attractiveness due to the reputation of their higher education sector, including the human capital investment considerations of the future students and their parents. The post-pandemic outlook for higher education is the bleakest for the poorest, our world will become more unequal in terms of internationalization of higher education as noted by Altbach and de Wit (2020).

Nonetheless, imagining some higher education systems or institutions which must face the cruel reality of closing down is not difficult, particularly when they are heavily reliant on fees generated from international student bodies. The world, even in the post-COVID-19 period, will certainly be ‘divided’ with the intensification of social and economic inequalities on a global scale due to their different rates of economic recovery (Marginson, 2020a, 2020b; Altbach & de Wit, 2020; O’Malley, 2017). This event would raise heated debates on the value of internationalisation of education, specifically when people have casted doubt on international education for ‘whose interests’ serve well before the present global health crisis (Mok, Wang, & Neubauer, 2020).

5.3. Policy implications

The findings presented above on Mainland China and Hong Kong university students’ attitudes towards studying abroad after the pandemic offer useful policy insights for HEIs across different parts of the world, specifically when institutions have mainly relied on Chinese students as one of their primary funding sources or incomes. For small cities developed as university towns across the UK, Europe, the US and Australia, the present survey indicates that even these towns would welcome Chinese students to stay with them for international learning, whether they feel safe and secured would become major factors influencing their study plans. Are we prepared to embrace the internationalisation of education even when the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is over? Is it ethical to accept foreign students if local residents are unprepared to adapt to diverse understandings and experiences when managing the global health crisis, including the acceptance of ‘wearing face masks’ as a preventive measure? These critical issues challenge us to come together for reflections (Mok, 2020a).

Amongst the top popular destinations in this study, Hong Kong’s position reaches the second, surpassing that of the UK. As an international metropolis, Hong Kong is a popular choice for Mainland China students to pursue further studies. This survey about Chinese students’ plans for overseas learning was conducted after another survey reported that citizens living in the Greater Bay Area (GBA) in Guangdong Province hold negative perceptions of Hong Kong earlier in April 2020 (Lingnan University, 2020b). Witnessing the protests and social unrest as a response to the Hong Kong Government’s attempts to introduce the Fugitive Offenders amendment bill in 2019, the GBA survey shows that people in Guangdong China no longer consider Hong Kong friendly, safe and well-managed in terms of urban governance. Such perceptions would inevitably affect Mainland students’ preference to make Hong Kong their destination for further studies. Whether people outside the city perceive Hong Kong as performing well in social management, safety, tolerance and friendliness would have a direct influence on their decisions about studying and working in Hong Kong.

Although the above data indicate declining interest in international learning, Hong Kong stands out as a popular destination for those who opt for overseas learning, although GBA citizens no longer consider the city as friendly and safe as it should be. A thriving world city depends on attracting and retaining world talents. One reason accounting for the popular choice of Hong Kong as a destination for international learning may be related to what Holliday and Postiglione argued: “Hong Kong universities were largely unencumbered by government bureaucracy because of their high degree of institutional autonomy. They could therefore act quickly to sustain instruction, research, and knowledge exchange [during the COVID-19 crisis]” (Holliday & Postiglione, 2020, p. 42). The two surveys presented above draw valuable policy insights not only for the Hong Kong Government but also for the society at large. The city is facing unprecedented challenges. Concerted efforts must urgently be put together to deal with the competition within and outside the GBA and rebuild a friendly and hospitable Hong Kong. After fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, academic leaders in Hong Kong must develop appropriate strategies to attract students from the GBA to visit the city for higher education and seriously engage with universities in the GBA to promote innovation-centric entrepreneurship.

6. Conclusion

Despite the hot debate persisting on whether the COVID-19 pandemic will cause the end of the internationalisation of higher education, the pandemic evidently has a profound influence on the global higher education (Marginson, 2020a), specifically on international student mobility. The pandemic will significantly decrease international student mobility due to travel restrictions, campus closure and students and families’ consideration of health and safety. Compared with the traditional pull–push factors for international student mobility, the COVID-19 pandemic has re-ordered the factors that students are considering to study abroad. As health and safety become the primary concerns for Mainland China and Hong Kong students under the pandemic, the neighbouring East Asian countries and regions, such as Hong Kong (for Mainland students), Japan and Taiwan, become their first few options due to their expected better management of the pandemic and post-pandemic crisis, apart from their close proximity to Mainland China and Hong Kong.

Analysing the above findings in relation to students in Mainland China and Hong Kong when choosing their destinations for overseas learning, the above analysis has shown that the existing literature reviewed in the earlier part of the article fails to offer sufficient explanations for the factors determining student choices. More specifically, when personal safety matters related to individual wellbeing and socially friendly environments are becoming increasingly important variables affecting students’ plans for overseas learning against the COVID-19 crisis context, we must engage in a critical review of the existing literature when analysing international student mobility. One major area for serious research in this field is to analyse how global politics and geopolitical factors influence the futures of international higher education, particularly when the relationship between China and the US has worsened since 2019. Hence, we should bring in the geo-political and broader political economic factors when analysing the futures of student mobility.

6.1. Research limitations

The present research adopts a quantitative method by using an online platform for distributing survey questionnaires to the respondents targeted for the study. The advantage of such a research method is its relative ease, particularly taking advantage of the exiting research projects with the same target population. However, the research team recognises well the limitations of the studies as the sampled respondents could not represent the broader student bodies in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Such an online survey would have encouraged the research team to reach out to a wider range of students in Hong Kong and Mainland China. The data, after careful cleaning and analysis, could still offer useful insights to understand the subject matter under review.

Footnotes

This article is based on a working paper of the Centre for Global Higher Education based in the UK, with further revisions. The authors thank the Institute of Policy Studies and School of Graduate Studies of Lingnan University for offering funding support to conduct the surveys.

References

- Altbach P.G. Impact and adjustment: Foreign students in comparative perspective. Higher Education. 1991;21(3):305–323. [Google Scholar]

- Altbach P., de Wit H. University World News; 2020. Post pandemic outlook for HE is bleakest for the poorest.https://www.universityworldnews.com/page.php?page=UW_Main April 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Amoah P., Mok K.H. Emerald Blog; 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic and internationalisation of higher education: International students’ knowledge, experiences and wellbeing.https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/topics/coronavirus/blog/covid-19-pandemic-and-internationalisation-higher-education-international June 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Austin L., Shen L. Factors influencing Chinese students’ decisions to study in the United States. Journal of International Students. 2016;6(3):722–732. [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Overseas Study Service Association (BOSSA) BOSSA; Beijing: 2020. Coronavirus’ impact on Chinese students and agents.https://www.bossa-cossa.org/coronavirus-impact-on-chinese-agents-students-studyabroad [Google Scholar]

- Bodycott P. Choosing a higher education study abroad destination: What Mainland Chinese parents and students rate as important. Journal of Research in International Education. 2009;8(3):349–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Stanford University Press; Staford, CA: 2001. Masculine domination. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs S. An exploratory study of the factors influencing undergraduate student choice: The case of higher education in Scotland. Studies in Higher Education. 2006;31(6):705–722. [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla-Boado H., Hu Y., Soysal Y.N. Why study abroad? Sorting of Chinese students across British universities. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2018;39(3):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chao C.N., Hegarty N., Angelidis J., Lu V.F. Chinese students’ motivations for studying in the United States. Journal of International Students. 2019;7(2):257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.H. Choosing Canadian graduate schools from afar: East Asian students’ perspectives. Higher Education. 2007;54:759–780. [Google Scholar]

- China’s Ministry of Education . China’s Ministry of Education; Beijing: 2020. China’s Ministry of Education issues the first warning for studying abroad in 2020.http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/202006/t20200609_464131.html [Google Scholar]

- Cozart D.L., Rojewski J.W. Career aspirations and emotional adjustment of Chinese international graduate students. SAGE Open. 2015;5(4) doi: 10.1177/2158244015621349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deviney D., Vrba T., Mills L., Ball E. Why some students study abroad and others stay? Research in Higher Education Journal. 2014;25:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Durnin M. British Council; London: 2020. Covid-19 update: China survey results.https://education-services.britishcouncil.org/insights-blog/covid-19-update-china-survey-results?_ga=2.183165667.436377671.1596516253-1764238916.1596516253 [Google Scholar]

- Findlay A. An assessment of supply and demand-side theorizations of international student mobility. International Migration. 2011;49(2):162–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fong V.L. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2011. Paradise redefined: Transnational Chinese students and the quest for flexible citizenship in the developed world. [Google Scholar]

- Goris J.A.Q. UNESCO; Paris: 2020. How will COVID-19 affect international academic mobility?https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/2020/06/26/how-will-covid-19-affect-international-academic-mobility/ [Google Scholar]

- Heisel M. Berkeley News; 2020. COVID-19: The end of or revival of international higher education.https://news.berkeley.edu/2020/05/07/covid-19-the-end-or-revival-of-international-higher-education/ 7 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Helms R.M. Higher Education Today; 2020. Can internationalization survive coronavirus? You need to see my data.https://www.higheredtoday.org/2020/03/04/can-internationalization-survive-coronavirus-need-see-data/ 4 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Herman P.C. Inside Higher Ed; 2020. Online learning is not the future.https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/views/2020/06/10/online-learning-not-future-higher-education-opinion June 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday I., Postiglione G. In: Higher education in Southeast Asia and beyond. Yeong L.H., editor. Head Foundation; Singapore: 2020. Higher education and the 2020 outbreak: We’ve been here before. [Google Scholar]

- Hossler D., Gallagher K.S. Studying student college choice: A three-phase model and the implications for policymakers. College and University. 2020;62(3):207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M., Hartocollis A. The New York Times; 2020. U.S. Rescinds plan to strip visas from international students in online classes.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/14/us/coronavirus-international-foreign-student-visas.html July 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Bankart C.A., Jiang X., Brazil A.M. In: Understanding international students from Asia in American Universities: Learning and living globalization. Ma Y., Garcia-Murillo M.A., editors. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. Understanding the college choice process of Asian international students; pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Leask B., Green W. University World News; 2020. Is the pandemic a watershed for internationalization.https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200501141641136 May 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. An investigation of factors determining the study abroad destination choice: A case study of Taiwan. Journal of Studies in International Education. 2013;18(4):362–381. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. Exploring motivations for studying abroad: A case study of Taiwan. Tourism Analysis. 2017;22(4):523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.S. A theory of migration. Demography. 1966;3(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W. Study abroad influencing factors: An investigation of socio-economic status, social, cultural, and personal factors. Ursidae: The Undergraduate Research Journal at the University of Northern Colorado. 2016;5(3):6. [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Bray M. Cross-border flows of students for higher education: Push–pull factors and motivations of mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong and Macau. Higher Education. 2007;53(6):791–818. [Google Scholar]

- Lingnan University . Lingnan University; Hong Kong: 2020. Fighting COVID-19 @ Lingnan University: Discovery, service, and education.https://www.ln.edu.hk/sgs/covid-19/dse/ [Google Scholar]

- Lingnan University . Lingnan University; Hong Kong: 2020. Joint survey of Lingnan University and South China University of Technology shows that Greater Bay Area residents in Mainland China consider epidemic prevention is done better in mainland than in Hong Kong and Macau.https://ln.edu.hk/research-and-impact/research-press-conferences/joint-survey-of-lingnan-university-and-south-china-university-of-technology-shows-that-great-bay-area-residents-in-mainland-china-consider-epidemic-prevention-is-done-better-in-mainland-than-in-hong-kong-and-macau [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Zhu W. Factors influencing student choice of transnational higher education in China. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Frontiers of Educational Technologies. 2019:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson S. Times Higher Education; 2020. Global HE as we know it has forever changed.https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/global-he-we-know-it-has-forever-changed# March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson S. Centre for Global Higher Education; Oxford, UK: 2020. Covid-19 and the market model of higher education: Something has to give, and it won’t be the pandemic.https://www.researchcghe.org/blog/2020-07-20-covid-19-and-the-market-model-of-higher-education-something-has-to-give-and-it-wont-be-the-pandemic/ [Google Scholar]

- Martel M. Institute of International Education; Washington, DC: 2020. COVID-19 effects on U.S. higher education campus: From emergency response to planning for future student mobility.https://www.iie.org/en/Research-and-Insights/Publications/COVID-19-Effects-on-US-Higher-Education-Campuses-Report-2 [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarol T., Soutar G.N. “Push‐pull” factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management. 2002;16:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado S. International student mobility and the impact of the pandemic. BizEd: AACSB International. 2020 https://bized.aacsb.edu/articles/2020/june/covid-19-and-the-future-of-international-student-mobility June 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H. Massification of higher education, graduate employment and social mobility in the Greater China region. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2016;37(1):51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H. Springer; Singapore: 2017. Managing international connectivity, diversity of learning and changing labour markets: East Asian perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H. University Worldnews; 2020. Will Chinese students want to study abroad post-COVID-19? 4 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H. Impact of COVID-19 on overseas studies. Paper Presented at the Seminar on Higher Education in the Plague Year: The Transformative Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic, 21 May 2020. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H., Kang Y.Y. 2020. China’s quest for world-class university status: A critical review of its history, achievements and impacts. Unpublished under review. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H., Wu A.M. Higher education, changing labour market and social mobility in the era of massification in China. Journal of Education and Work. 2016;29(1):77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H., Wang Z.Q., Naubauer D. Contesting globalisation and implications for higher education in the Asia–Pacific region: Challenges and prospects. Higher Education Policy. 2020;33(3):397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Mok K.H., Welch T., Kang Y.Y. Government innovation policy and higher education: The case of Shenzhen, China. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 2020;42(2):194–212. [Google Scholar]

- New Oriental . New Oriental Education & Technology Group; Beijing: 2020. Report on Chinese students’ overseas study 2020. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley B. University Worldnews; 2017. TNE and study abroad may perpetuate inequality. 17 June, https://www.universityworldnes.com/article.php?story=20170617060527350, (Accessed 15 July 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira D.B., Soares A.M. Studying abroad: Developing a model for the decision process of international students. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 2016;38(2):126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schulmann P. World Education Services; New York: 2020. Perfect storm: The impact of the coronavirus crisis on international student mobility to the United States.https://wenr.wes.org/2020/05/perfect-storm-the-impact-of-the-coronavirus-crisis-on-international-student-mobility-to-the-united-states [Google Scholar]

- Tan S.L. South China Morning Post; 2020. “You Chinese virus spreader”: After Coronavirus, Australia has an anti-Asian racism outbreak to deal with.https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/people/article/3086768/you-chinese-virus-spreader-after-coronavirus-australia-has-anti May 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tang D. The Seattle Times; 2014. Chinese seek freedom, edge at U.S. high schools.http://seattletimes.com/html/nationworld/2024313609_chinesehighschoolxml.html 16 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tesar M. Towards a post-Covid-19 “New Normality?”: Physical and social distancing, the move to online and higher education. Policy Future in Education. 2020;18(5):556–559. [Google Scholar]

- The University of Hong Kong . University of Hong Kong; Hong Kong: 2020. Scholarship, funding and fees: HKU Presidential PhD Scholarship (HKU-PS)https://www.gradsch.hku.hk/gradsch/prospective-students/scholarship-funding-and-fees#1 [Google Scholar]

- Tohuku University Graduate School of Education . Graduate School of Education Webinar Series 2020; 2020. Transforming higher education in the era of new normal: Responses and prospects.https://www.tohoku.ac.jp/en/events/special_event/webinar_series_2020.html June 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute of Statistics . UNESCO Institute of Statistics; Paris: 2019. Education: Inbound internationally mobile students by country of origin – students from China, both sexes. [Google Scholar]

- University and College Union . University and College Union; London: 2020. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on university finance.https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/10871/LE_report_on_covid19_and_university_finances/pdf/LEreportoncovid19anduniversityfinances [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q. Motivations and decision-making processes of Mainland Chinese students for undertaking master’s programs abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education. 2014;18(5):426–444. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W., Mok K.H. Critical reflections on Mainland China and Taiwan overseas returnees’ job search and career development experiences in the rising trend of anti-globalization. Higher Education Policy. 2020;33(3):413–436. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W., Mok K.H., Jiang J. Higher Education Policy Institute; Oxford, UK: 2020. Hong Kong university students’ online learning experiences under the Covid-19 pandemic.https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2020/08/03/hong-kong-university-students-online-learning-experiences-under-the-covid-19-pandemic [Google Scholar]

- Zhiyan Consulting Group . Zhiyan Consulting Group; Beijing: 2020. Consulting report of the operation situations and strategies of China’s studying abroad market, 2019–2025. [Google Scholar]