Abstract

COVID-19 has been related to several autoimmune diseases, triggering the appearance of autoantibodies and endothelial dysfunction. Current evidence has drawn attention to vasculitis-like phenomena and leukocytoclastic vasculitis in some COVID-19 patients. Moreover, it has been hypothesized that COVID-19 could induce flares of preexisting autoimmune disorders. Here, we present two patients with previously controlled IgA vasculitis who developed a renal and cutaneous flare of vasculitis after mild COVID-19, one of them with new-onset ANCA vasculitis. These patients were treated with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants achieving successful response. We also provide a focused literature review and conclude that COVID-19 may be associated with triggering of vasculitis and could induce flares of previous autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Vasculitis, COVID-19, Autoimmune diseases, Flare, ANCA-associated vasculitis

Introduction

Novel severe acute respiratory syndrome by coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) disease (COVID-19) ranges from asymptomatic to severe cases, which are characterized by a severe acute respiratory syndrome. Even mild forms of COVID-19 have been associated with various autoimmune manifestations and accordingly this infection has been proposed as a trigger of several autoimmune diseases [1]. Molecular mimicry and hyperinflammation due to hyperstimulation of the immune system seem to be the potential mechanisms of autoimmunity in COVID-19 [2] and may lead to the appearance of previously non-existent autoantibodies [3]. Furthermore, complement activation in COVID-19 has been shown to activate platelets and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [1, 4] involved in multiple autoimmune diseases [3].

A study conducted in China in patients with critical SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia showed a 50% prevalence of antinuclear antibodies [5] and another study found anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in 13% of these patients [6]. Other studies showed an increased incidence of positivity for lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid antibodies in COVID-19 patients [7].

Furthermore, there are some reports in the literature describing de novo development of autoimmune diseases associated with COVID-19 [2, 3, 8]. Additionally, patients with preexisting autoimmune diseases may undergo reactivation of their disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection; however, the evidence in the literature about this process is limited. Herein, we report two cases of reactivation of IgA vasculitis after COVID-19 infection.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 27-year-old white male was admitted to our rheumatology department in January 2021 presenting with diffuse arthralgias and cutaneous purpuric lesions in the upper and lower limbs. The patient had been diagnosed with Henoch–Schönlein purpura 3 years earlier, but had no other medical history of interest. At diagnosis, the patient had cutaneous purpura, articular and renal disease (mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with IgA deposits). He was successfully treated with oral glucocorticoids for 1 year achieving sustained remission without subsequent relapses.

In our assessment, physical examination revealed generalized palpable purpura distributed over all the extremities, gluteal region and abdomen, without evidence of arthritis, gastrointestinal symptoms or associated fever. A month before, the patient had suffered an asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosed by positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test in nasopharyngeal swab sample, which was indicated due to close contact with a COVID-19-positive subject.

Laboratory results showed normal full blood count, liver and renal function tests, as well as normal coagulation profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein values. Serum IgA levels were increased (357 g/L), while IgG and IgM were normal and the rest of the autoimmune assays, including ANCAs, were negative. Urinalysis was normal.

Given the suspicion of an IgA vasculitis flare, a skin purpuric lesion was biopsied, showing histological results consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated predominant IgA deposition thereby confirming IgA vasculitis relapse. The patient received 50 mg/day of prednisone with improvement of purpuric lesions. Three months later, the patient developed microhematuria, with adequate renal function, which was resolved by treatment with azathioprine at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day.

Case 2

A 62-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our department with purpuric lesions in the upper limbs with no other associated symptoms. She had been diagnosed with IgA vasculitis four years before, which consisted of anterior scleritis, joint and cutaneous involvement with positive skin biopsy at two different times (immunofluorescence-confirmed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposition). ANCA antibodies were negative and C3 decrease was observed, consistent with hypocomplementemic IgA vasculitis. Treatment with high doses of glucocorticoids and methotrexate was enough to achieve remission, which was maintained after glucocorticoid withdrawal under methotrexate monotherapy.

In March 2020, the patient presented symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but did not require admission and recovered remaining isolated at home. She then tested positive for IgG COVID-19 antibodies in the next month. Three months later, the patient advanced her scheduled appointment to our clinic. Physical examination revealed a palpable purpura on arms, without signs of arthritis. She was afebrile and her pulse and blood pressure were normal. Laboratory results revealed a reduction in glomerular filtration rate (49 ml/min/1.73 m2 vs previous of 90 ml/min/1.73 m2), mild anemia and lymphopenia with normal acute phase reactants. Urinalysis showed microhematuria and proteinuria up to 1.4 g/24 h. ANCA determination tested positive for proteinase 3 (anti-PR3) antibodies (459 IU/ml, normal upper limit 20 IU/ml) with low complement levels of C3.

A percutaneous renal biopsy was performed showing findings of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with fibroepithelial crescents compatible with a diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. The patient was treated with 3 methylprednisolone boluses of 500 mg/day and intravenous rituximab (4 weekly doses of 375 mg/m2) as induction therapy, followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day. After 3 months, renal function was partially recovered, proteinuria and ANCA levels were notably reduced and cutaneous lesions were improved. Currently, the patient remains with 10 mg of oral prednisone and rituximab.

Search strategy and case selection

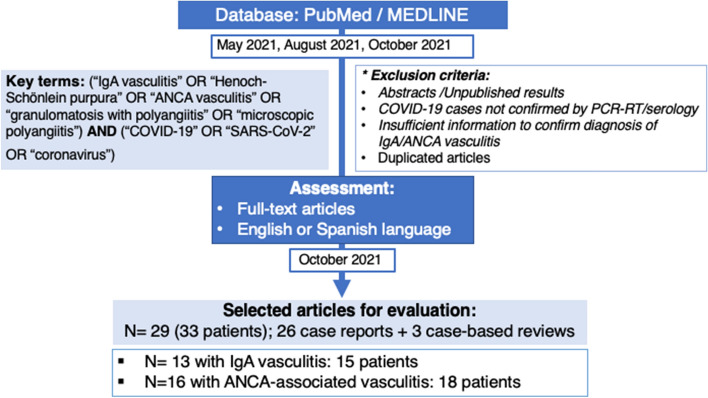

A literature review was performed to identify studies focused on the development of ANCA vasculitis or IgA vasculitis after COVID-19. Accordingly, MEDLINE database was accessed through PubMed and searched for articles published in English or Spanish between March 2020 and October 2021. The search strategy used the following key terms related to vasculitis and COVID-19: (“IgA vasculitis” OR “Henoch–Schönlein purpura” OR “ANCA vasculitis” OR “granulomatosis with polyangiitis” OR “microscopic polyangiitis”) AND (“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “coronavirus”). Search strategy is represented in Fig. 1. We selected only patients with confirmed positive test for COVID-19 by serology or RT-PCR in nasopharyngeal swab. Cases with insufficient information to confirm the diagnosis of IgA vasculitis or ANCA vasculitis (positive biopsy, positive ANCA or increase of IgA levels) were not considered. To capture all the available literature, articles were selected with no filter in terms of design, included case reports and case series, and with no limits in the age of the patients. Abstracts or not published results were not included. This search strategy was applied at three different times (May 2021, August 2021 and October 2021) covering until October 25th 2021. Finally, a total of 29 articles were selected for evaluation.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the bibliographic search strategy and selection criteria. ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, RT-PCR reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, SARS-CoV-2 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2

Results

We identified 16 reports describing 18 cases (12 women/6 men) of new-onset ANCA-associated vasculitis in COVID-19 patients and presumably related to this disease [8–23]. The main characteristics of these cases are presented in Table 1. In eight cases the onset of ANCA vasculitis coincided with the infection, six of them had pneumonia. Of the 18 cases, 16 presented organ-threatening disease: 13 patients presented renal involvement (pauci-immune glomerulonephritis) and 11 patients had diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, in 9 of these patients both diseases coexisted. Three patients also presented pulmonary involvement, pulmonary nodules with cavitary lesions in two patients and hyper eosinophilic bronchiolitis in one patient. Only seven patients had leukocytoclastic vasculitis and two patients had arthritis.

Table 1.

Reported cases of ANCA-associated vasculitis related to COVID-19

| Author [ref.] diagnosis |

Age (years); sex (M/F) |

Medical history | COVID-19 symptoms (diagnosis); time to vasculitis onset | Clinical manifestations | Type of ANCA | Non-GC immuno-modulators and biological therapies | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uppal et al. [8] | 64; M | Previous cryptogenic organizing pneumonia |

Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Glomerulonephritis |

P-ANCA: Anti-MPO |

Rituximab | Partial renal response |

| Uppal et al. [8] | 46; M | Diabetes mellitus | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Glomerulonephritis and leukocytoclastic vasculitis | Anti-PR3 | Rituximab | Complete response |

| Moeinzadeh et al. [9] | 25; M | None | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | C-ANCA |

CYC Plasmapheresis IVIG |

Partial renal response with stable creatinine Complete pulmonary improvement |

| Hussein et al. [10] | 37; F | None | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and arthritis |

C-ANCA: Anti-PR3 |

IVIG Plasmapheresis |

Death |

| Selvaraj et al. [11] | 60; F | Diabetes mellitus, allergic rhinitis | Upper respiratory tract symptoms and myopericarditis (RT-PCR +); 4 wks | Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

C-ANCA: Anti-PR3 |

Rituximab Plasmapheresis |

Partial pulmonary and renal response |

| Jalalzadeh et al. [12] | 48; F | Diabetes mellitus and scleroderma | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR); 5 wks | Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

P-ANCA: Anti-MPO |

Rituximab | Unknown |

| Singh et al. [13] | 46; F | Rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (RT-PCR +); 6 wks | Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

P-ANCA: Anti-MPO |

Rituximab | Remission |

| Powell et al. [14] | 12; F | None | Asymptomatic (IgG serology +); unknown | Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

P-ANCA: Anti-MPO |

Rituximab CYC |

Improvement in clinical status |

| Merveilleux du Vignaux et al. [15] | 59; F |

HBV chronic infection, Asthma |

Upper respiratory tract symptoms (RT-PCR +); 4 wks | Hypereosinophilic bronchiolitis and leukocytoclastic vasculitis | Anti-MPO | Azathioprine | Favorable outcome |

| Izci Duran et al. [16] | 26; M | None |

Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage |

P-ANCA: Anti-MPO |

CYC Plasmapheresis |

Lung findings regressed Hemodialysis was continued after 2 doses of cyclophosphamide |

| Izci Duran et al. [16] | 36; F | None | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (RT-PCR +); few weeks | Glomerulonephritis and cavitary lung lesions | Anti-PR3 | CYC | Renal improvement |

| Reiff et al. [17] | 17; M | None |

Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Pulmonary nodules with cavitary lesions and fever |

C-ANCA Anti-PR3 |

Rituximab | Asymptomatic status and significant improvement in nodules size |

| Maritati et al. [18] | 64; F | Hypertension | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Glomerulonephritis and antiphospholipid syndrome | Anti-PR3 |

CYC Plasmapheresis Rituximab |

Renal function gradually ameliorated with stable creatinine |

| Lind et al. [19] | 40; M | None | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (RT-PCR +); 10 days | Glomerulonephritis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and arthritis |

C-ANCA: Anti-PR3 |

Rituximab | The patient continued to improve clinically in the months following discharge |

| Patel et al. [20] | 77; F | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus |

Upper respiratory tract symptoms; 6 wks |

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | Anti-MPO | Plasmapheresis | Death |

| Allena et al. [21] | 60; F | Coronary artery disease, asthma, hypertension, dyslipidemia | Unknown; 4 wks | Glomerulonephritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | Anti-MPO |

Plasmapheresis Rituximab |

Pulmonary and renal improvement |

| Fireizen et al. [22] | 17; M | Obesity, asthma | Pneumonia (RT-PCR); 2 months | Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis |

P-ANCA Anti-MPO |

Plasmapheresis CYC |

Complete response |

| Mashinchi et al. [23] | 21; F | SLE | Pneumonia (RT-PCR); concomitant | Glomerulonephritis with a flare of SLE (malar rash, oral ulcers, arthralgia) | C-ANCA |

Plasmapheresis MMF, CYC |

Death |

| Current case | 62; F | Previous IgA vasculitis | Upper respiratory symptoms; 3 months | Glomerulonephritis with palpable purpura |

C-ANCA Anti-PR3 |

Rituximab | Complete response |

ANCA anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CYC cyclophosphamide, Anti-MPO anti-myeloperoxidase antibodies, Anti-PR3 anti-proteinase 3 antibodies, F female, GC glucocorticoids, HBV hepatitis B virus, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulins, M, male, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, RT-PCR reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, wks weeks

Regarding the type of ANCA, anti-MPO antibodies were more frequently detected than anti-PR3 antibodies (nine and seven patients, respectively). All patients received steroids and most cases were treated with immunosuppressive combined therapy: nine with rituximab, nine with plasmapheresis, six with cyclophosphamide (CYC), two with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), one with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and the other one with azathioprine. In the follow-up, most patients responded well to glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents but two patients died as a result of the disease (both with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage) [10, 20]. Another patient died as a consequence of multiple infections [23]. Notably, three of these cases had a preexistent autoimmune disease [12, 13, 23]. Another case simultaneously developed an antiphospholipid syndrome [18].

Concerning IgA vasculitis related to COVID-19, 15 cases (12 men; 3 women) in 13 reports have been published to date [24–36], which are summarized in Table 2. Half of the cases were diagnosed in childhood. These cases presented new-onset IgA vasculitis, most of them with palpable purpura (13 patients) and 8 patients developed renal disease (IgA nephropathy). Additionally, eight patients presented with gastrointestinal involvement and three patients presented with arthritis. In eight patients, the onset of vasculitis coincided with the infection. All of these patients were treated with glucocorticoids and four patients received immunosuppressants for renal involvement (1 rituximab, 2 MMF, 1 CYC) with favorable renal response in all cases [25, 30, 36]. No deaths were identified.

Table 2.

Reported cases of IgA vasculitis related to COVID-19

| Case | Age (years); sex (M/F) |

Medical history | COVID-19 symptoms (diagnosis); time to vasculitis onset | Clinical characteristics | Non-GC immuno-modulators and biological therapies | Outcome follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. [24] | 30; M | None | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, abdominal pain and arthralgia |

None | Asymptomatic. Preserved renal function and dramatically reduced proteinuria |

| Suso et al. [25] | 78; M | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, aortic valve stenosis, and bladder cancer in remission | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); 3 weeks |

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, and arthritis |

Rituximab |

On discharge, serum creatinine had improved, but the patient persisted with proteinuria and hematuria. Cutaneous purpura markedly improved |

| Hoskins et al. [26] | 2; M | None | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposits, abdominal pain and hematochezia |

None | Complete resolution of skin findings; abdominal symptoms also resolved |

| Allez et al. [27] | 24; M | Crohn’s disease | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposits, abdominal pain and arthritis |

None | Unknown |

| Barbetta et al. [28] | 62; M | None | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); 10 days | Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposits, IgA nephropathy, abdominal pain and hematochezia | None | Improvement of renal function and progressive remission of abdominal pain and skin purpura |

| AlGhoozi et al. [29] | 4; M | None | Upper respiratory tract symptoms; (RT-PCR +); 5 weeks | Palpable purpura and arthralgia | None | At one week the rash was still present bilaterally, but he had remained pain free |

| Sandhu et al. [30] | 22; M | None | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant |

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, arthritis, IgA nephropathy, abdominal pain and vomiting |

Mycophenolate mofetil | Cutaneous lesions, joint involvement and abdominal symptoms resolved, urinalysis normalized after 2 weeks |

| Jacobi et al. [31] | 3; M | Corrected Hirschsprung disease | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Palpable purpura and abdominal pain | None | Abdominal pain responded well to glucocorticoids on discharge |

| Huang et al. [32] | 65; F | Hypertension | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant | IgA nephropathy | None |

Asymptomatic 3 months later, eGFR normal, UACR 33.61 mg/g |

| El Hasbani et al. [33] | 16; M | None | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Palpable purpura, abdominal pain and hematochezia | None | Rapid clinical improvement |

| Nakandakari et al. [34] | 4; F | None | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (IgM/ IgG +); 8 days | Palpable purpura, abdominal pain and hematochezia | None | Progressive decrease in abdominal pain and purpuric lesions |

| Falou et al. [35] | 8; M | None | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Palpable purpura | None | Rash and ankle pain resolved |

| Oñate et al. [36] | 87; M | Hypertensive cardiomyopathy | Upper respiratory tract symptoms (IgG +); 2 months | Leukocytoclastic vasculitis with IgA deposits and nephropathy (without biopsy) | None | At 5 months of follow-up, he had complete recovery of renal function |

| Oñate et al. [36] | 64; F | Hypertension, CKD | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); 9 months | IgA nephropathy | Cyclophosphamide | At 4 months of follow-up, the patient had improvement in renal function and reduced proteinuria |

| Oñate et al. [36] | 84; M | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, COPD, CHF | Pneumonia (RT-PCR +); concomitant | Palpable purpura and IgA nephropathy | Mycophenolate mofetil | At 10 months of follow-up, the patient partially recovered kidney function with negative proteinuria and maintains microhematuria |

| Current case | 27; M | Previous IgA vasculitis | Asymptomatic (RT-PCR +); 4–5 weeks | Flare of IgA vasculitis (palpable purpura, arthralgia and IgA nephropathy) | Azathioprine | Complete cutaneous and renal response |

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CHF congestive heart failure, eGFR glomerular filtration rate, F female, GC glucocorticoids, M male, RT-PCR reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, UACR urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio

Discussion

COVID-19 is bringing back many aspects of autoimmune diseases that seemed forgotten. Indeed, SARS-CoV-2 infection could break self-tolerance and trigger systemic autoimmunity. Several reports have suggested that COVID-19 may be followed by immune activation and the development of several autoimmune manifestations [2, 3, 37]; however, there is currently a lack of robust evidence supporting SARS-CoV-2 as the causal trigger of these phenomena [38].

Although the association between COVID-19 and the relapse of vasculitis found in our cases cannot be fully demonstrated and could be incidental, the chronology of events suggests a potential role of the viral infection on the onset of both vasculitis flares. Indeed, other viruses have been proposed as a trigger of vasculitis based on molecular mimicry, tropism for vascular endothelium, immune complex deposition within the vessel walls and autoantibody production [39–41]. Causal relationships have been well established between hepatitis C virus and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and between hepatitis B virus and polyarteritis nodosa [39, 40].

Current evidence supports that the mechanisms involved in SARS-CoV-2 regulation of autoantibody generation, endothelial inflammation and dysfunction, complement activation and NET production may lead to vasculitis [1–4]. Vasculitis-like phenomena during COVID-19 infection have been described in the literature and numerous reports have described cutaneous vascular lesions in COVID-19 patients [37, 42]. Therefore, some authors suggest that virus–host interactions may lead to both direct and indirect microvasculature damage through endothelial cell inflammation [42]. Additionally, thrombosis, lymphocytic endothelitis, and apoptotic bodies have been found in COVID-19 autopsies [37, 42]. Furthermore, several studies have reported the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in cutaneous biopsies from COVID-19 patients obtained during the active or convalescent phases of this infection [43–45].

We present two cases of patients with prior history of IgA vasculitis with ocular, renal, skin and articular involvement, both of them in sustained remission, who developed a new flare of vasculitis shortly after SARS-CoV-2 infection. One case suffered mild COVID-19, while the other remained asymptomatic.

Case 1 had a relapse of the disease with hematuria, arthralgia and cutaneous flare and the second case presented with cutaneous and renal disease consistent with ANCA-associated vasculitis. The absence of ANCA in the patient´s previous history, along with C3 consumption in a well-documented IgA vasculitis prompted us to consider a newly induced ANCA-associated vasculitis; however, recurrent low C3 levels pointed to a relapse of a hypocomplementemic IgA vasculitis, likely in the context of an overlapping vasculitis. We cannot definitely rule out that both entities were present prior COVID19 infection, as ANCA levels were not systematically analyzed during remission at subsequent follow-up.

Our two patients suffered severe manifestations of vasculitis (kidney involvement in both patients). This finding was also described in the reported cases of vasculitis related to COVID-19: renal disease was reported in 15/18 patients with ANCA vasculitis and in 8/15 patients with IgA vasculitis. In line with our findings, the reviewed cases of post-COVID-19 ANCA vasculitis were more severe and with a worse prognosis than those with IgA vasculitis, showing organ-threatening disease in 88% of the cases (16/18) and three deaths. Both renal and pulmonary involvement were very common in ANCA-associated vasculitis. In addition, the reported cases showed a predominance of IgA vasculitis in males and ANCA-associated vasculitis in females.

Current evidence on flares of preexisting autoimmune diseases in COVID-19 patients is very limited. Flares of SLE in patients with COVID-19 have been described [46]. A study in a cohort of Hispanic COVID-19 patients from United States with rheumatic diseases identified COVID-19 positivity as a risk factor for disease flares [47]. To date, we have not found publications reporting cases of relapses of previous controlled IgA vasculitis associated with COVID-19.

Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there are no descriptions in the literature of flares of vasculitic diseases associated with COVID-19. Therefore, our cases provide valuable information supporting the novel hypothesis that COVID-19 could act as an immune trigger for vasculitis contributing to flares of prior disease, even with new autoantibody-induced manifestations.

Conclusion

COVID-19 infection could be associated with vasculitis triggering and could induce flares of previous autoimmune diseases. To our knowledge, this is the first description of vasculitis reactivation following COVID-19 infection in patients with preexisting IgA vasculitis. These findings suggest a causal relationship between COVID-19 and vasculitis, although further research is needed to establish solid evidence about this subject.

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Gómez-Gutiérrez, PhD, from the “Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria, IIS-Princesa”, Hospital de La Princesa, Madrid, Spain, for his critical reading and his help in editing this manuscript.

Author contributions

Conception or design of the work: SC. Acquisition of data: CV. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript CV, SC and RGV. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: CV. Review and approval of the final version of the manuscript: all authors. Supervision: SC and RGV.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Cristina Valero, Juan Pablo Baldivieso-Achá, Miren Uriarte, Esther F. Vicente-Rabaneda, Santos Castañeda and Rosario Garcia Vicuña declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the work submitted for publication.

Ethics statement

The patients of the two cases were fully informed, and we obtained signed informed consent to report their case.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Cristina Valero, Email: cristina.valmart@gmail.com.

Juan Pablo Baldivieso-Achá, Email: juanpablobaldiviesoacha@gmail.com.

Miren Uriarte, Email: miren_uriarte@hotmail.com.

Esther F. Vicente-Rabaneda, Email: efvicenter@gmail.com

Santos Castañeda, Email: scastas@gmail.com.

Rosario García-Vicuña, Email: mariadelrosario.garcia@salud.madrid.org.

References

- 1.Skendros P, Mitsios A, Chrysanthopoulou A, et al. Complement and tissue factor-enriched neutrophil extracellular traps are key drivers in COVID-19 immunothrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(11):6151–6157. doi: 10.1172/JCI141374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dotan A, Muller S, Kanduc D, David P, Halpert G, Shoenfeld Y. The SARS-CoV-2 as an instrumental trigger of autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(4):102792. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenfeld M, Tincani A, Andreoli L, et al. Covid-19 and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(8):102597. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veras FP, Pontelli MC, Silva CM, et al. SARS-CoV-2-triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID-19 pathology. J Exp Med. 2020;217(12):e20201129. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, Han T, Chen J, et al. Clinical and Autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(6):1077–1086. doi: 10.1111/cts.12805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Magira E, Alexopoulos H, et al. Autoantibodies related to systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases in severely ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1661–1663. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gkrouzman E, Barbhaiya M, Erkan D, Lockshin MD. Reality check on antiphospholipid antibodies in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(1):173–174. doi: 10.1002/art.41472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uppal NN, Kello N, Shah HH, et al. De novo ANCA-associated vasculitis with glomerulonephritis in COVID-19. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(11):2079–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moeinzadeh F, Dezfouli M, Naimi A, Shahidi S, Moradi H. Newly diagnosed glomerulonephritis during COVID-19 infection undergoing immunosuppression therapy, a case report. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2020;14(3):239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussein A, Al Khalil K, Bawazir YM. Anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) vasculitis presented as pulmonary hemorrhage in a positive COVID-19 patient: a case report. Cureus. 2020;12(8):e9643. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvaraj V, Moustafa A, Dapaah-Afriyie K, Birkenbach MP. COVID-19-induced granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(3):e242142. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-242142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jalalzadeh M, Valencia-Manrique JC, Boma N, Chaudhari A, Chaudhari S. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated glomerulonephritis in a case of scleroderma after recent diagnosis with COVID-19. Cureus. 2021;13(1):e12485. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh S, Vaghaiwalla Z, Thway M, Kaeley GS. Does withdrawal of immunosuppression in rheumatoid arthritis after SARS-CoV-2 infection increase the risk of vasculitis? BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(4):e241125. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-241125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell WT, Campbell JA, Ross F, Peña Jiménez P, Rudzinski ER, Dickerson JA. Acute ANCA vasculitis and asymptomatic COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4):e2020033092. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-033092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.du Merveilleux Vignaux C, Ahmad K, Tantot J, Rouach B, Traclet J, Cottin V. Evolution from hypereosinophilic bronchiolitis to eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis following COVID-19: a case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(128(1)):11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izci Duran T, Turkmen E, Dilek M, Sayarlioglu H, Arik N. ANCA-associated vasculitis after COVID-19. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(8):1523–1529. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04914-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiff DD, Meyer CG, Marlin B, Mannion ML. New onset ANCA-associated vasculitis in an adolescent during an acute COVID-19 infection: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):333. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02812-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maritati F, Moretti MI, Nastasi V, et al. ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis and anti-phospholipid syndrome in a patient wITH SARS-CoV-2 infection: just a coincidence? Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2021;11(2):214–220. doi: 10.1159/000517513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lind E, Jameson A, Kurban E. Fulminant granulomatosis with polyangiitis presenting with diffuse alveolar haemorrhage following COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(6):e242628. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-242628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel R, Amrutiya V, Baghal M, Shah M, Lo A. Life-threatening diffuse alveolar hemorrhage as an initial presentation of microscopic polyangiitis: COVID-19 as a likely culprit. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14403. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allena N, Patel J, Nader G, Patel M, Medvedovsky B. A rare case of SARS-CoV-2-induced microscopic polyangiitis. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15259. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fireizen Y, Shahriary C, Imperial ME, Randhawa I, Nianiaris N, Ovunc B. Pediatric P-ANCA vasculitis following COVID-19. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(10):3422–3424. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mashinchi B, Aryannejad A, Namazi M, et al. A Case of C-ANCA positive systematic lupus erythematous and anca-associated vasculitis overlap syndrome superimposed by COVID-19: a fatal trio. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1093/mrcr/rxab007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li NL, Papini AB, Shao T, Girard L. Immunoglobulin-a vasculitis with renal involvement in a patient with COVID-19: a case report and review of acute kidney injury related to SARS-CoV-2. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2021;8:2054358121991684. doi: 10.1177/2054358121991684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suso AS, Mon C, Alonso IO, et al. IgA vasculitis with nephritis (Henoch-Schonlein purpura) in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:2074–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoskins B, Keeven N, Dang M, Keller E, Nagpal R. A child with COVID-19 and immunoglobulin a vasculitis. Pediatr Ann. 2021;50(1):e44–e48. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20201211-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allez M, Denis B, Bouaziz JD, et al. COVID-19-related IgA vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(11):1952–1953. doi: 10.1002/art.41428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbetta L, Filocamo G, Passoni E, Boggio F, Folli C, Monzani V. Henoch-Schönlein purpura with renal and gastrointestinal involvement in course of COVID-19: a case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(129(2)):191–192. doi: 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/5epvob. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AlGhoozi DA, AlKhayyat HM. A child with Henoch-Schonlein purpura secondary to a COVID-19 infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(1):e239910. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandhu S, Chand S, Bhatnagar A, et al. Possible association between IgA vasculitis and COVID-19. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1):e14551. doi: 10.1111/dth.14551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobi M, Lancrei HM, Brosh-Nissimov T, Yeshayahu Y. Purpurona: a novel report of COVID-19-related Henoch-Schonlein Purpura in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(2):e93–e94. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Y, Li XJ, Li YQ, et al. Clinical and pathological findings of SARS-CoV-2 infection and concurrent IgA nephropathy: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:504. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Hasbani G, Taher AT, Jawad ASM, Uthman I. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: another COVID-19 complication. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/pde.14699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakandakari Gomez MD, Marin Macedo H, SeminarioVilca R. IgA vasculitis (Henoch Schönlein Purpura) in a pediatric patient with COVID-19 and strongyloidiasis. Rev Fac Med Humana. 2021;21(1):184–190. doi: 10.25176/RFMH.v21i1.3265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falou S, Kahil G, AbouMerhi B, Dana R, Chokr I. Henoch Schonlein Purpura as possible sole manifestation of Covid-19 in children. Acta Sci Paediatr. 2021;4(4):27–29. doi: 10.31080/ASPE.2021.04.0377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oñate I, Ortiz M, Suso A, et al. Ig A vasculitis with nephritis (henoch-schönlein purpura) after covid-19: a case series and review of the literature. Nefrologia. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2021.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novelli L, Motta F, De Santis M, Ansari AA, Gershwin ME, Selmi C. The JANUS of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases onset during COVID-19—a systematic review of the literature. J Autoimmun. 2021;117:102592. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calabrese L, Winthrop KL. Rheumatology and COVID-19 at 1 year: facing the unknowns. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(6):679–681. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-219957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teng GG, Chatham WW. Vasculitis related to viral and other microbial agents. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(2):226–243. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haq SA, Pagnoux C. Infection-associated vasculitides. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22(1):109–115. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Konstantinov KN, Ulff-Møller CJ, Tzamaloukas AH. Infections and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: triggering mechanisms. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(3):201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.020.15a22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker RC. COVID-19-associated vasculitis and vasculopathy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(3):499–511. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gisondi P, PIaserico S, Bordin C, Alaibac M, Girolomoni G, Naldi L. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a clinical update. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(11):2499–2504. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caputo V, Schroeder J, Rongioletti F. A generalized purpuric eruption with histopathologic features of leucocytoclastic vasculitis in a patient severely ill with COVID-19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):579–581. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camprodon Gómez M, González-Cruz C, Ferrer B, Barberá MJ. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis in a patient with COVID-19 with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR in skin biopsy. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(10):e238039. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-238039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gracia-Ramos AE, Saavedra-Salinas MA. Can the SARS-CoV-2 infection trigger systemic lupus erythematosus? A case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:799–809. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04794-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fike A, Hartman J, Redmond C, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19 and rheumatic disease flare in a US cohort of Latino patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/art.41656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]