Abstract

A new pathway to synthesize poly(hydroxyalkanoic acids) (PHA) was constructed by simultaneously expressing butyrate kinase (Buk) and phosphotransbutyrylase (Ptb) genes of Clostridium acetobutylicum and the two PHA synthase genes (phaE and phaC) of Thiocapsa pfennigii in Escherichia coli. The four genes were cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pBR322, and the resulting hybrid plasmid, pBPP1, conferred activities of all three enzymes to E. coli JM109. Cells of this recombinant strain accumulated PHAs when hydroxyfatty acids were provided as carbon sources. Homopolyesters of 3-hydroxybutyrate (3HB), 4-hydroxybutyrate (4HB), or 4-hydroxyvalerate (4HV) were obtained from each of the corresponding hydroxyfatty acids. Various copolyesters of those hydroxyfatty acids were also obtained when two of these hydroxyfatty acids were fed at equal amounts: cells fed with 3HB and 4HB accumulated a copolyester consisting of 88 mol% 3HB and 12 mol% 4HB and contributing to 68.7% of the cell dry weight. Cells fed with 3HB and 4HV accumulated a copolyester consisting of 94 mol% 3HB and 6 mol% 4HV and contributing to 64.0% of the cell dry weight. Cells fed with 3HB, 4HB, and 4HV accumulated a terpolyester consisting of 85 mol% 3HB, 13 mol% 4HB, and 2 mol% 4HV and contributing to 68.4% of the cell dry weight.

Poly(hydroxyalkanoic acids) (PHAs) are synthesized in bacteria via different pathways. In Ralstonia eutropha (formerly Alcaligenes eutrophus) (40) and most other poly(3-hydroxybutyric acid) [poly(3HB)]-accumulating bacteria, poly(3HB) is synthesized from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) through three enzymes: β-ketothiolase condenses two molecules of acetyl-CoA to β-acetoacetyl-CoA, an NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase catalyzes the formation of d-(−)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA (3HB-CoA), and PHA synthase finally polymerizes 3HB-CoA to poly(3HB) (27, 29). A modified synthesis pathway for poly(3HB) was found in Rhodospirillum rubrum. Instead of d-(−)-3HB-CoA, l-(+)-3HB-CoA is formed from β-acetoacetyl-CoA by an NADH-dependent reductase. l-(+)-3HB-CoA is then converted to its d-(−) isomer with enoyl-CoA hydratases (6, 18). In pseudomonads, synthesis of PHA consisting of medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids occurs either through fatty acid de novo synthesis, which is linked to PHA synthesis by an acyl-CoA transferase (20), or through coupling to the β-oxidation pathway (10, 31). Detailed reviews on these and other PHA biosynthesis pathways are available in the literature (31–33).

Although low-molecular-weight poly(3HB) was detected in association with other molecules in Escherichia coli (21–23), this species does not synthesize high-molecular-weight poly(3HB) or other PHAs, nor does it accumulate such polyesters as carbon storage compounds, even if a foreign PHA synthase gene is expressed in the cells. However, by expressing the entire PHA operon from, e.g., R. eutropha, cells of E. coli synthesized and accumulated poly(3HB) (27, 29). Since the first successful cloning of the PHA operon of R. eutropha, many recombinant strains of E. coli that accumulated various other PHAs have been obtained. Besides a copolyester of 3HB and 3-hydroxyvaleric acid (3HV) [poly(3HB-co-3HV)] (28), recombinant strains of E. coli were obtained which produced polyesters containing 4-hydroxybutyric acid (4HB) such as poly(4HB) or poly(3HB-co-4HB) (9, 30) or polyesters containing medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids such as 3-hydroxydecanoic acid (13, 19).

In this study, we present a newly designed pathway for PHA synthesis from hydroxyfatty acids by employing the genes for butyrate kinase (Buk) and phosphotransbutyrylase (Ptb) from Clostridium acetobutylicum and the genes for PHA synthase from Thiocapsa pfennigii.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, media, and cultivation.

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains were cultivated at 37°C and were maintained in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 10 g of NaCl per liter) or M9 mineral salts medium (1) according to Sambrook et al. (25); ampicillin (100 mg/liter) was added when needed. Additional carbon sources were applied from filter-sterilized stock solutions as indicated in the text.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 Δ(lac-proAB) | Stratagene |

| K2006 | F− his− fadR16 fadA30 atoC49 atoA28; source of pJC7 | 11 |

| DH1 | F− endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK−) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 λ−; source of pBR322 | 7 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBR322 | Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pJC7 | Aprbuk+ptb+ | 4 |

| pBPP1 | Aprbuk+ ptb+ phaEC+ | This study |

| pBPP2 | Aprbuk+ ptb+ phaEC− | This study |

| pBPha | AprphaEC+ | This study |

Genetic manipulation.

Routine isolation of plasmid was done by the alkaline lysis method (25); plasmid restriction enzymatic digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis, and DNA ligation were performed by following procedures in a laboratory manual (25) and instructions from the manufacturers. DNA fragments were purified by using a Qiaquick gel extraction kit (catalog no. 28704; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Measurements of enzyme activity.

Buk activity was assayed in the direction of butyryl phosphate formation according to Hartmanis (8) modified from Rose (24). Enzymatic analysis was done in a total volume of 0.5 ml. After 5 to 10 min, the reaction was stopped by addition of 0.5 ml of 10% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid, and then 2 ml of acidic FeCl3 solution was added. The absorbance at 540 nm was measured, and enzyme activity was calculated on the basis of a molar extinction coefficient of 0.169 mM−1 cm−1 (4).

Ptb activity was measured in the direction of butyryl-CoA to butyryl phosphate conversion, by monitoring the reaction of CoA with 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) at 412 nm (39). The assay contained in a total volume of 0.5 ml 0.1 M potassium phosphate, 0.2 mM butyryl-CoA, and 1.0 mM DTNB. An extinction coefficient of 13.61 mM−1 cm−1 was used.

PHA synthase was determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the release of CoA at 412 nm (37). The assay contained 1 mM DTNB, 20 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mM 3HB-CoA in 150 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5).

Accumulation of PHAs.

For examination of PHA accumulation, strains were cultivated at 37°C in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of medium and were agitated at 200 rpm. LB or M9 medium containing 1% (wt/vol) glucose was used. Various hydroxyfatty acids were added at the beginning of or during cultivation to final concentrations of 0.2 or 0.4% (wt/vol) as indicated in the text.

Isolation and analysis of polyesters.

Cells from 50 ml of medium were harvested after 2 to 3 days cultivation by centrifugation (4,000 rpm for 10 min in a Minifuge RF, type no. 3360 [Heraeus Septech]) and washed three times. For quantative determination of PHAs in the cells and analysis of the constituents, 5 to 10 mg of lyophilized cells was subjected to methanolysis in the presence of 15% sulfuric acid, and the resulted hydroxyacyl methylesters were analyzed by gas chromatography as described previously (3, 35).

Determination of protein concentrations.

Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford (2).

Chemicals.

d-(−)-3HB and 4HB were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). 4HV was prepared by alkaline hydrolysis of 4-hydroxyvalerolactone. NaOH (10 N) was added to 4-hydroxyvalerolactone to a final volume of 50% while stirring. The pH of the suspension was adjusted between 11 and 12. The reaction proceeded under stirring on ice until the pH was stable and no phase separation occurred. After the reaction was completed, the hydrolysate was adjusted to a pH of 7.0 with 1 N HCl.

RESULTS

Construction of plasmids.

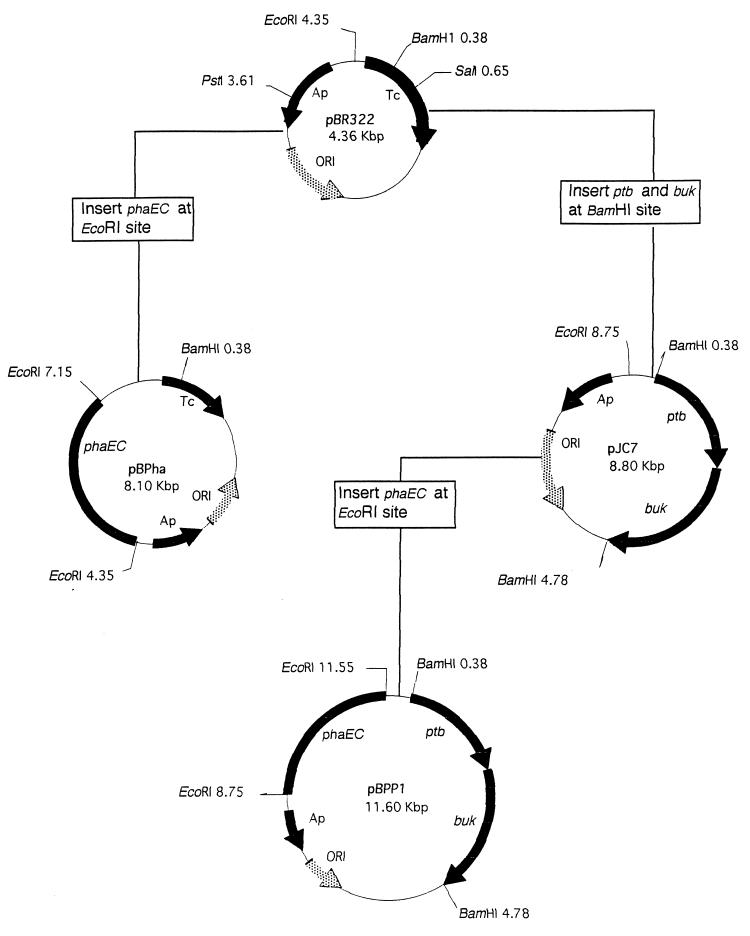

Plasmid pJC7, which contained a 4.4-kbp genomic fragment encoding the Buk and Ptb genes from C. acetobutylicum in the BamHI site of pBR322 (4), was used to ligate a 2.8-kbp EcoRI restriction fragment of pHP1014:B28 encoding the PHA synthase genes (phaEC) of T. pfennigii (16) into this plasmid. The resulting hybrid plasmid, pBPP1, harbored all four genes for Buk, Ptb, and PHA synthase (Fig. 1). In parallel, plasmid pBPha was constructed by inserting only the PHA synthase genes into pBR322 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Construction of plasmids used in this study. Plasmid pJC7 was generated by Cary et al. (4).

Analysis of Buk, Ptb, and PHA synthase activities confirmed that all three enzymes were expressed in functionally active form in the recombinant E. coli JM109(pBPP1). Plasmids pJC7 and pBPha conferred only Buk and Ptb activities or PHA synthase activity, respectively, to the recombinant strains of JM109 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Specific activities of relevant enzymes in recombinant strains of E. coli JM109 strains harboring different plasmidsa

| Strain | Sp act (U/mg of protein)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Buk | Ptb | PHA synthase | |

| JM109(pJC7) | 18 | 3.0 | NDb |

| JM109(pBPP1) | 10 | 3.8 | 0.1 |

| JM109(pBPP2) | 15 | 2.5 | ND |

| JM109(pBPha) | ND | ND | 0.5 |

Strains were cultivated in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of LB medium with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and 100 mg of ampicillin per liter at 37°C and at 200 rpm for 24 h.

ND, not detected.

During construction of the plasmids, we also found a plasmid, referred to as pBPP2, that conferred Buk and Ptb activities but no PHA synthase activity to the cells (Table 2). Restriction analysis of the plasmid revealed that the 2.8-kbp EcoRI fragment harboring phaEC existed in this plasmid, but opposite the direction in pBPP1, indicating that the orientation of phaEC genes is relevant for expression of the PHA synthase.

Detection of poly(3HB) in different media.

As found in our experiments, accumulation of PHAs depended on the supply of hydroxyfatty acids as carbon sources. When cultivated in LB or M9 medium with 1% glucose, E. coli JM109(pBPP1) accumulated only traces of poly(3HB) (Table 3). However, when 3HB was fed in addition to glucose, JM109(pBPP1) accumulated significant amounts of poly(3HB), amounting to more than 40% of the cell dry matter (Table 3) if cultivation was done in M9 medium. In LB medium supplemented with glucose and 3HB, poly(3HB) was also accumulated, but to only approximately 5% of the cell dry matter.

TABLE 3.

Accumulation of poly(3HB) by recombinant strains of E. coli JM109 harboring different plasmidsa

| Medium | Poly(3HB) content (% of cell dry wt)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| JM109 (pJC7) | JM109 (pBPP1) | JM109 (pBPha) | |

| M9 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| LB | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| M9 + glucose (1%) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| LB + glucose (1%) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| M9 + glucose (1%) + 3HB (0.4%) | 0.4 | 43.3 | 0.5 |

| LB + glucose (1%) + 3HB (0.4%) | 0.4 | 5.1 | 0.4 |

Strains were cultivated in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of medium with the indicated carbon source, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and 100 mg of ampicillin per liter at 37°C and at 200 rpm for 72 h.

Accumulation of homopolyesters other than poly(3HB).

E. coli JM109(pBPP1) was also examined for the capability to synthesize and accumulate PHAs from 4HB or 4HV (Table 4). Poly(4HB) accumulated to up to 4.8% of the cell dry matter when 0.2% 4HB was added two times at the beginning and after 24 h of cultivation to cultures in M9 medium containing 1% glucose. Under the same conditions, the strain accumulated poly(4HV) to 1.3% of the cell dry weight if 4HV instead of 4HB was provided. Obviously, poly(4HB) and poly(4HV) were not as efficiently accumulated as poly(3HB) (Tables 3 and 4).

TABLE 4.

Accumulation of PHAs by recombinant strains of E. coli JM109 harboring plasmid pBPP1 during cultivation on hydroxyfatty acidsa

| Carbon source(s) in addition to glucose | PHA content (% of cell dry wt) | Composition of PHA (mol%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HB | 4HB | 4HV | ||

| 3HB | 40.8 | 100 | NDb | ND |

| 4HB | 4.8 | ND | 100 | ND |

| 4HV | 1.3 | ND | ND | 100 |

| 3HB + 4HB | 68.7 | 88 | 12 | ND |

| 3HB + 4HV | 64.0 | 94 | ND | 6 |

| 3HB + 4HB + 4HV | 68.4 | 85 | 13 | 2 |

Cells were cultivated in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 ml of M9 medium with 1% (wt/vol) glucose, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and 100 mg of ampicillin per liter at 37°C and at 200 rpm for 3 days; 0.2% (wt/vol) each fatty acid was fed after 24 and 48 h.

ND, not detected.

Accumulation of copolyesters by JM109(pBPP1).

Besides the ability to accumulate the homopolyesters poly(3HB), poly(4HB), and poly(4HV), the strains were also investigated for the capability to accumulate copolyesters (Table 4). When 3HB and a second hydroxyfatty acids were fed, the cells accumulated large amounts of copolyesters. Although 3HB was the predominant constituent in all experiments done, 4HB or 4HV contributed 12 or 6 mol% of the constituents if 4HB or 4HV was the second carbon source, respectively. When all three hydroxyfatty acids were fed at equal amounts, a terpolyester consisting of 85 mol% 3HB, 13 mol% 4HB, and 2 mol% 4HV was accumulated. These results indicated that the three enzymes involved in this novel PHA biosynthesis pathway preferred 3HB as substrates.

DISCUSSION

For the first time, Buk and Ptb of C. acetobutylicum were coupled in vivo to the PHA synthase of T. pfennigii to establish a novel PHA biosynthesis pathway that was expressed in a functionally active form in recombinant E. coli. This engineered metabolic pathway allowed the synthesis and accumulation of polyesters containing not only 3HB but also 4HB and/or 4HV as constituents. Synthesis of PHAs containing these constituents depended greatly on the provision of the respective hydroxyfatty acids as carbon sources. If more than one hydroxyfatty acid was provided, copolyesters and even a terpolyester were synthesized. The lower efficiencies for the incorporation of 4HB and 4HV into PHAs reflected the substrate preference of the enzymes involved. We noticed that recombinant strains of Pseudomonas putida expressing PHA synthase of T. pfennigii accumulated PHAs containing significant portions of 3-hydroxyhexanoate or 4HV (15, 26), which suggested a rather broad substrate specificity of this PHA synthase. The lower molar ratio of 4HV of the PHAs synthesized in this study (2 to 6 mol% versus 20 mol% in previous reports) is most probably due to the low conversion of 4HV to 4HV-CoA in E. coli. We recently demonstrated low activities of Buk and Ptb toward 4HV and 4-hydroxyvaleryl phosphate, respectively (17). From this study and the literature, it became also evident that the PHA synthase of T. pfennigii is unlikely to use 4HV-CoA as a substrate.

In addition, this study clearly demonstrated that a PHA biosynthesis pathway engineered in a previous study by an in vitro approach (17) is functionally active in vivo in E. coli. Therefore, in vitro engineering of pathways may be a useful strategy to evaluate whether the establishment of a particular pathway in a bacterium by in vivo metabolic engineering is feasible. This is a general conclusion from this study in addition to having obtained a better poly(4HB)-producing strain.

Production of homopolyesters or copolyesters of 4HB in bacteria has attracted many researchers. Synthesis of copolyesters containing 4HB was found in R. eutropha (11, 12, 36, 38), Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava (5), in recombinant strains of E. coli (9), and in several other bacteria. The high amounts of the copolyester (up to 68.4% by weight) in E. coli JM109(pBPP1) made this strain competitive to other producers. Further studies to increase the ratio of 4HB in these copolyesters will be conducted.

PHAs have been detected in several anaerobic heterotrophic bacteria such as Clostridium botulinum, Desulfovibrio sapovarans, and Syntrophomonas wolfei (for a review, see reference 31). PHAs were also detected in biological samples from anaerobic environments (for a review, see reference 31). Neither molecular nor enzymatic studies on the biosynthesis of PHAs in these bacteria have been done, and it is not known whether these anaerobes use PHA synthesis pathways similar to those found in R. eutropha or other well-studied aerobic bacteria. This study indicates a putative alternative pathway to synthesize hydroxyacyl-CoA thioesters, which are the substrates of PHA synthase, presuming that hydroxyfatty acids are produced in anaerobic bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The provision of a research scholarship within the special bioscience program to S.-J. Liu from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst is gratefully acknowledged.

We are grateful to P. Dürre (Universität Ulm, Ulm, Germany) and G. Bennett (Rice University, Houston, Tex.) for providing E. coli K2006 and pJC7.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlas R M, Parks L C. Handbook of microbiological media. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandl H, Gross R A, Lenz R N, Fuller R C. Pseudomonas oleovorans as a source of poly(β-hydroxyalkanoates) for potential applications as biodegradable polyesters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1977–1982. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.1977-1982.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cary J W, Petersen D J, Papoutsakis E T, Bennett G N. Cloning and expression of Clostridium acetobutylicum phosphotransbutyrylase and butyrate kinase genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4613–4618. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4613-4618.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi M H, Yoon S C, Lenz R W. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyric acid-co-4-hydroxybutyric acid) and poly(4-hydroxybutyric acid) without subsequent degradation by Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1571–1577. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1570-1577.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukui T, Shiomi N, Doi Y. Expression and characterization of (R)-specific enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:667–673. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.667-673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D. Techniques for transformation of Escherichia coli. In: Glover D M, editor. DNA cloning: a practical approach. Vol. 1. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1985. pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmanis M G N. Butyrate kinase from Clostridium acetobutylicum. J Biol Chem. 1986;262:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hein S, Söhling B, Gottschalk G, Steinbüchel A. Biosynthesis of poly(4-hydroxybutyric acid) by recombinant strains of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huijberts G N M, De Rijk T C, De Waard P, Eggink G. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of Pseudomonas putida fatty acid metabolism routes involved in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1661–1666. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1661-1666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins L S, Nun M D. Genetic and molecular characterization of the genes involved in short-chain fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: the ato system. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:42–52. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.42-52.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunioka M, Kawaguchi Y, Doi Y. Production of biodegradable copolyesters of 3-hydroxybutyrate and 4-hydroxybutyrate by Alcaligenes eutrophus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;30:569–573. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunioka M, Nakamura Y, Doi Y. New bacterial copolyesters produced in Alcaligenes eutrophus from organic acids. Polym Commun. 1988;29:174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langenbach S, Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Functional expression of the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Escherichia coli resulting in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liebergesell M, Hustede E, Timm A, Steinbüchel A, Fuller R C, Lenz R W, Schlegel H G. Formation of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) by phototrophic and chemolithotropic bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1991;155:415–421. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebergesell M, Mayer F, Steinbüchel A. Analysis of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid biosynthesis genes of anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria reveals synthesis of a polyester exhibiting an unusual composition. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:292–300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, S.-J., and A. Steinbüchel. Exploitation of butyrate kinase and phosphotransbutyrylase from Clostridium acetobutylicum for in vitro biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyric acids). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Moskowitz G J, Merrick J M. Metabolism of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate: enzymatic synthesis of d-(−)-β-hydroxybutyryl-CoA by an enoyl hydratase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochemistry. 1969;8:2748–2755. doi: 10.1021/bi00835a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qi Q-S, Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates in Escherichia coli expressing the PHA synthase gene phaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of PhaC1 and PhaC2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehm B H A, Krüger N, Steinbüchel A. A new metabolic link between fatty acid de novo synthesis and polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24044–24051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reusch R, Sadoff H L. Putative structure and functions of a poly-β-hydroxybutyrate/calcium polyphosphate channel in bacterial plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4176–4180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reusch R N, Hiske T W, Sadoff H L. Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate membrane structure and its relationship to genetic transformability in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:553–562. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.553-562.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reusch R N, Hiske T W, Sadoff H L, Harris R, Beveridge T. Cellular incorporation of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate into plasma membranes of Escherichia coli and Azotobacter vinelandii alters native membrane structure. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:435–444. doi: 10.1139/m87-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose I A. Acetate kinase of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1955;1:591–595. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmack G, Gorenflo V, Steinbüchel A. Biotechnological production and characterization of polyesters containing 4-hydroxyvaleric acid and medium-chain-length hydroxyalkanoic acids. Macromolecules. 1998;31:644–649. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubert P, Steinbüchel A, Schlegel H G. Cloning of the Alcaligenes eutrophus genes for synthesis of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid (PHB) and synthesis of PHB in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5837–5847. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5837-5847.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slater S, Gallaher T, Dennis D E. Production of poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) in a recombinant Escherichia coli strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1089–1094. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1089-1094.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slater S C, Voige W H, Dennis D E. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 poly-β-hydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4431–4436. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4431-4436.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song S-S, Hein S, Steinbüchel A. Production of poly(4-hydroxybutyric acid) by fed-batch cultures of recombinant strains of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 1999;21:193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinbüchel A. Polyhydroxyalkanoic acids. In: Byrom D, editor. Biomaterials. Stockton Press, New York: Macmillan; 1991. pp. 123–213. , N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinbüchel A, Füchtenbusch B. Bacterial and other biological systems for polyester production. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;16:419–427. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinbüchel A, Brämer C, Füchtenbusch B, Gorenflo V, Hein S, Jossek R, Kalscheuer R, Langenbach S, Qi Q-S, Rehm B H A, Song S-S, Tran H. Poly(hydroxyalkanoic acids) biosynthesis pathways. In: Steinbüchel A, editor. Biochemical principles and mechanisms of biosynthesis and biodegradation of polymers. New York, N.Y: Wiley-VCH; 1998. pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sudesh K, Fukui T, Doi Y. Genetic analysis of Comamonas acidovorans polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and factors affecting the incorporation of 4-hydroxybutyrate monomer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3437–3443. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3437-3443.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timm A, Byrom D, Steinbüchel A. Formation of blends of various poly(3-hydroxyalkanoic acids) by a recombinant strain of Pseudomonas oleovorans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1990;33:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valentin H, Schönebaum A, Steinbüchel A. Identification of 4-hydroxybutyric acid as a constituent of biosynthetic polyhydroxyalkanoic acids from bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;36:507–514. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valentin H E, Steinbüchel A. Application of enzymatically synthesized short-chain-length hydroxy fatty acid coenzyme A thioesters for assay of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;40:699–709. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valentin H, Zwingmann G, Schönebaum A, Steinbüchel A. Metabolic pathway for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) from 4-hydroxybutyrate by Alcaligenes eutrophus. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:43–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiesenborn D P, Rudolph F B, Papoutsakis E T. Phosphotransbutyrylase from Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 and its role in acidogenesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:317–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.2.317-322.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Yano I, Hotta H, Nishiuchi Y. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. nov. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]