Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this paper is to provide a review of the existing literature on racial disparities in quality of palliative and end-of-life care and to demonstrate gaps in the exploration of underlying mechanisms that produce these disparities.

Background:

Countless studies over several decades have revealed that our healthcare system in the United States consistently produces poorer quality end-of-life for Black compared with White patients. Effective interventions to reduce these disparities are sparse and hindered by a limited understanding of the root causes of these disparities.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, CINAHL and PsychInfo for research manuscripts that tested hypotheses about causal mechanisms for disparities in end-of-life care for Black patients. These studies were categorized by domains outlined in the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) framework, which are biological, behavioral, physical/built environment, sociocultural and health care systems domains. Within these domains, studies were further categorized as focusing on the individual, interpersonal, community or societal level of influence.

Results:

The majority of the studies focused on the Healthcare System and Sociocultural domains. Within the Health Care System domain, studies were evenly distributed among the individual, interpersonal, and community level of influence, but less attention was paid to the societal level of influence. In the Sociocultural domain, most studies focused on the individual level of influence. Those focusing on the individual level of influence tended to be of poorer quality.

Conclusions:

The sociocultural environment, physical/built environment, behavioral and biological domains remain understudied areas of potential causal mechanisms for racial disparities in end-of-life care. In the Healthcare System domain, social influences including healthcare policy and law are understudied. In the sociocultural domain, the majority of the studies still focused on the individual level of influence, missing key areas of research in interpersonal discrimination and local and societal structural discrimination. Studies that focus on individual factors should be better screened to ensure that they are of high quality and avoid stigmatizing Black communities.

Introduction

For several decades, the palliative care literature has documented disparities in end-of-life (EOL) care for Black patients in the United States. Black patients receive hospice services at a lower rate, are more likely to be hospitalized and receive care in an intensive care unit at the EOL and have lower rates of completion of advance directives.(1–20) Even more concerning is the finding that bereaved family members of Black patients are more likely to report that their loved-one received poor quality EOL care.(21–23) Early studies examining causes of EOL disparities focused on differences beliefs, behavior and characteristics of Black patients and families.(5, 7, 9, 24–30)

The Black Lives Matter movement and the COVID-19 pandemic have brought renewed attention to racial disparities in health care. This environment has opened the door for a re-examination of the focus of health disparities literature. In particular, scholars such as Dr. Rhea Boyd have clearly identified the need to focus on various forms of racism; structural, institutional and interpersonal, as explanatory factors in health disparities research.(31) Boyd and colleagues argue that research focusing on biological and behavioral characteristics of Black patients obfuscates the role of racism in producing disparities. Similarly, Dr. Rachel Hardeman examines the framing of research questions in health services research, finding that focusing on a deficit model of health disparities upholds racism within our research infrastructure.(32)

These critiques invite us to systematically examine the state of EOL health disparities research in order to identify gaps in our framing of research questions. Where might we be missing opportunities to name and examine various types of racism as primary drivers of disparities? What research practices may be inadvertently upholding racist ideologies? In 2018 the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) published a research framework aimed at conceptualizing the “wide array of determinants that promote or worsen minority health or cause, sustain or reduce health disparities.”(33) This framework is meant to widen the lens though which researchers ask questions about etiological factors and intervention targets. The NIMHD framework identifies domains of determinants of disparities (biological, behavioral, sociocultural and environmental) and further categorizes these domains using the socioecological model into four levels of influence; individual, interpersonal, community and societal. The authors noted that in the broader health disparities literature, there is an overrepresentation of studies examining the individual level with fewer focusing on community and societal levels of influence. This suggests that institutional and structural racism are under-investigated in the broader health disparities literature.

We aimed to use the NIMHD framework to evaluate the literature on disparities in EOL outcomes for Black patients and families. This review may reveal areas of investigation that are under-represented in the literature and suggest a path forward to a more comprehensive understanding of the etiologies of critical disparities in quality of EOL care.

Methods:

We searched the PubMed, CINAHL and PsychInfo databases for articles published between 5/17/2011 and 5/17/2021 using the search terms palliative care, advance care planning, advance directives, surrogate decision making, living will terminal care, hospice, resuscitation orders, DNR orders, end-of-life care, terminal illness African Americans and Black. An example of the search strategy for PubMed can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion Criteria

Articles including Black or African American adult population in the United States and patients with serious or terminal illness OR healthy adults in studies of advance care planning pertaining to future serious or terminal illness were included. Studies with quantitative methods including cross-sectional, cohort, case/control, pre/post intervention studies and randomized controlled trials were included. Articles published in the English language in peer reviewed journals were included. Finally, articles must address causes of disparities in type of EOL care (rather than chronic care) delivered, processes of care (e.g. palliative care consult), symptom management, advance care planning or patient/family ratings of quality of EOL care to be included. Studies of interventions to ameliorate these causes were included.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies that documented disparities alone without exploring causal mechanisms. Qualitative studies, editorials and reviews were excluded. Case studies/case series, pilot, exploratory and feasibility studies were excluded. Studies of instrument development and validation studies were excluded. Studies focusing on populations outside of the United States and pediatric populations were excluded. Studies focused on physician aid in dying or physician assisted suicide were excluded.

Categorization and Evaluation of Quality

One investigator, EC, evaluated all articles and a second investigator (SY or AG or JN or JW) independently evaluated them for risk of bias and categorization in the twenty categories possible by combining the 5 domains × 4 levels of influence using the NIMHD framework.(33) Articles could be placed in more than one category as many evaluated multiple causal factors. We used the National Institute of Health quality assessment tools to evaluate risk of bias in each article (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools). Differences in categorization or quality rating were resolved with discussion.

Results

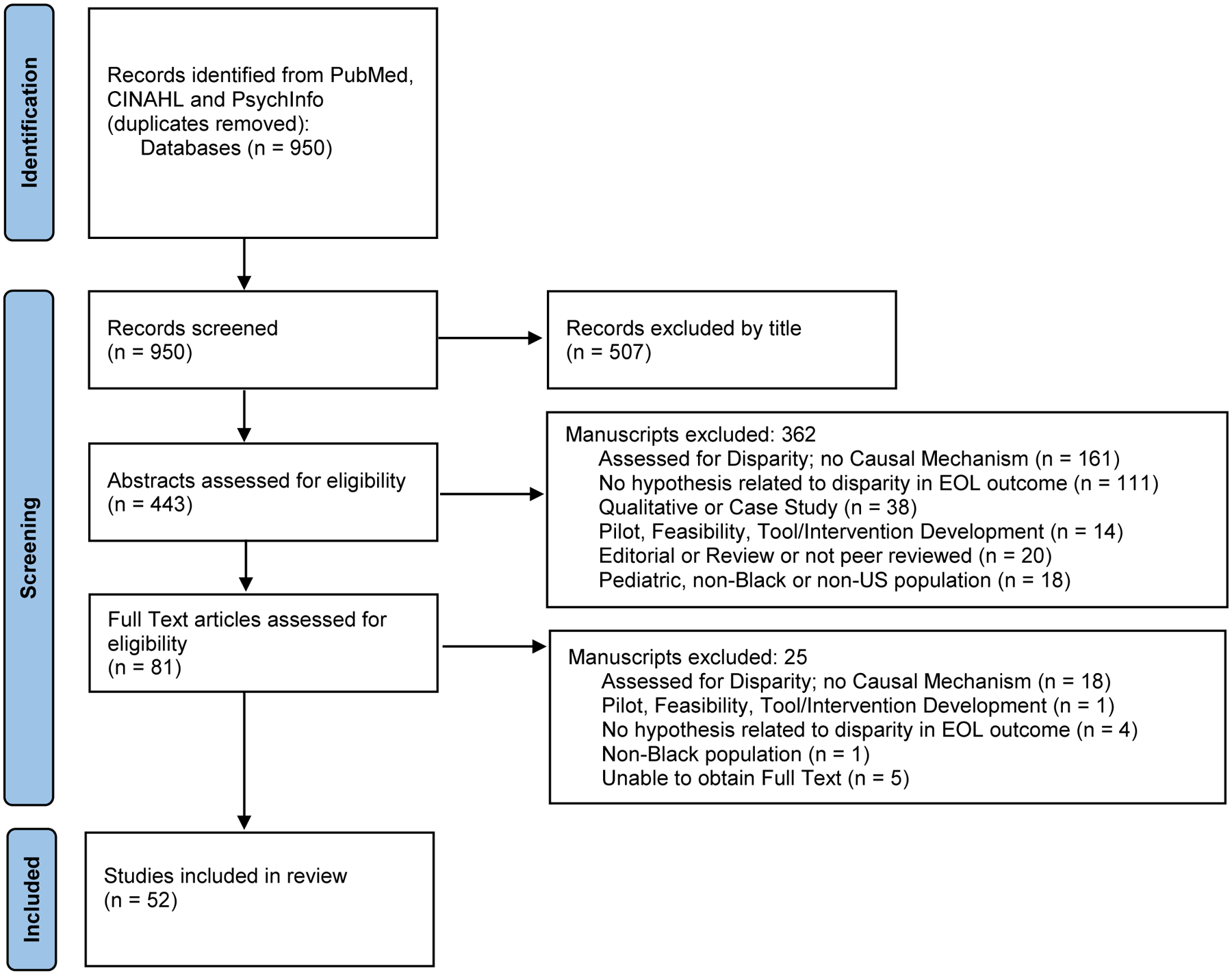

After removal of duplicates, 950 unique titles were returned from the PubMed, PsychInfo and CINAHL databases from 5/17/2011 – 5/17/2021. Of those, 507 were excluded by title and 443 abstracts were reviewed for inclusion and exclusion criteria. 391 articles were excluded either by abstract or full-text review including 179 which evaluated for disparities without examining a causal mechanism, 115 which did not include a hypothesis related to disparities in EOL outcomes, 92 which were not the accepted article type or population of interest and 5 for which we were unable to obtain the full text of the article (Figure 1). Of the studies which evaluated for disparities without examining a causal mechanism, 28 failed to detect racial disparities or demonstrated better outcomes for Black patients, including two that found increased use of inpatient palliative care services(34, 35) and two that showed increased caregiver psychological wellbeing and resilience.(36, 37) After the screening process, 52 articles were included in this review (see Appendix 2 for a table detailing each article).

Figure 1:

Flow diagram showing screening of manuscripts

Domains of Influence

Figure 2 depicts the number of times each category in the NIMHD 20-category framework was represented in the studies. There are more than 52 counts in this figure because some articles included more than one category in their investigation resulting in a total of 73 categorizations detailed below.

Figure 2:

Distribution of Studies by Domains and Levels of Influence

Biological

Five studies explored the biological domain, and all focused on the individual level of influence.(38–42) These studies generally found that factors such as age, functional disability, and comorbid conditions such as memory problems and chronic pain were all related to both preferences for types of EOL care(38, 40–42) and advance care planning.(39) For example, younger Black patients with chronic kidney disease were more likely to prefer life-prolonging care compared with whites of the same age groups, but differences were attenuated in older age groups,(38) and markers of increased disease severity such as number of hospitalizations, emergency room visits and prescription medications were associated with increased advance care planning for Black women.(42) All of the studies had a moderate or high risk of bias, including limits on generalizability due to samples from small geographic regions.

Behavioral

Five studies explored the behavioral domain.(39, 40, 43–45) Three studies with low to moderate risk of bias focused on the individual level of influence.(39, 43, 45) Some, but not all, measures of religious practice were associated with decreased advance care planning, and religious practice explained some of the racial disparity in advance care planning.(39, 43) Increased social and physical activity were related to increased advance care planning for white but not Black older individuals.(45) The two studies focusing on the interpersonal level of influence conducted with Black patients with HIV had a moderate to high level of bias.(40, 44) Social support increased the likelihood of nonaggressive EOL treatment preferences,(40) and advance care planning.(44)

Physical/Built Environment

Two studies, both with low risk of bias, examined the physical/built environment.(46, 47) Community resources such as lower quality of available housing and transportation(47) and lower median income(46) were associated with reduced hospice utilization and supply.

Sociocultural Environment

Eighteen studies explored the sociocultural domain; eleven explored the individual level of influence. Several studies with varying risk of bias found that cultural religious beliefs about God’s control over the timing of death (sometimes referred to as fatalism) were more common among Black people (48) and associated with less advance care planning (2, 39, 49) and less of a preference for comfort-oriented EOL care.(50) However, one study with low risk of bias failed to show a relationship between religious affiliation, beliefs and practices with disparities in EOL care.(51) Religious affiliation was examined as an intervention to reduce disparities in a cluster randomized controlled trial in large urban Black churches, which demonstrated improved caregiver knowledge of treatment options and improved self-efficacy for EOL decision-making.(52)

Two studies with low and moderate risk of bias explored sociodemographic factors. One study used the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), which included socioeconomic status and household composition within the composite of 15 factors, and found that higher social vulnerability was related to reduced use of hospice in Black but not white patients, however, it is unknown which factors within the SVI are driving this outcome.(47) Black people were less likely than white people to engage in advance care planning in one study, but younger age explained more of this difference than household income, household composition and education.(53) In a study of patients with serious illness with moderate risk of bias, mistrust and perceived discrimination explained the lower rates of advance care planning in Black patients compared with white patients to a greater extent than socioeconomic factors.(54) Finally, one study with low risk of bias found that sociodemographic factors such as education, net worth and urban residence attenuated but did not eliminate racial disparities in EOL care spending.(55)

Six studies examined the interpersonal level of influence. Two studies with moderate risk of bias explored the role of family caregivers. Conner et al. showed that the presence of a caregiver increased the likelihood that Black patients would be enrolled in hospice, while Zhang et al. found in a small convenience sample that Black family caregivers of patients with advanced lung cancer were more likely than white caregivers to believe that treatment was curative and to associate hospice care with hopelessness.(56, 57) One randomized controlled trial leveraged the role of family caregivers by offering an intensive advance care planning session involving communication with family and friends to reduce disparities in advance care planning.(58)

Interpersonal interactions with physicians were also explored. A randomized controlled study with low risk of bias revealed that physicians exhibit implicit bias in their nonverbal communication with Black compared with White standardized patients, which could have downstream effects on quality of EOL care.(59) This conclusion is supported by another study with moderate risk of bias, which showed that experience of racial discrimination explained much of the difference between Black and white patients in rates of advance care planning.(54) Finally, a cluster randomized controlled trial with moderate risk of bias showed that social networks in churches could be leveraged to enhance knowledge of EOL treatment options.(52)

Three studies with moderate risk of bias looked at community effects. Home ownership increased the likelihood of advance care planning among Black people but not white people.(53) When controlling for estate planning, which may be a proxy for access to legal services, disparities between Black and white patients in advance care planning were no longer significant.(60) Conner and colleagues found that religious affiliation explained a small portion of the variance in hospice use among Black patients.(57)

A single study with low risk of bias explored the societal level of influence. Fishman and colleagues found that the Black news media was less likely to report stories about cancer that included information about treatment failures, adverse effects or that focused on death and dying compared with the mainstream media.(61)

Health Care Systems

The majority of the studies (35) examined the health care system domain. Ten studies focused on the individual level of influence. Only three of these had a low risk of bias. Several examined patient preferences. One found that personal health values and preferences did not fully explain disparities in advance care planning,(43) while another found that discussion of preferences did not affect disparities in EOL health care spending.(55) Another study with moderate risk of bias found that while there were no significant racial differences in the influence of religious/spiritual beliefs, cultural beliefs and distrust of healthcare on preferences for care at EOL in patients with chronic kidney disease, Black patients who were less than 65 years-old were more likely than similar-age white patients to prefer life-extending care.(38)

Two studies on pharmacologic outcomes found that patient preferences were related to differences in EOL outcomes. One study with moderate risk of bias found that the patient’s preference to focus on cure rather than pain management predicted lower adherence to opioid analgesia regimens among Black patients,(62) and another study with moderate risk of bias showed that EOL treatment preferences explained differences in willingness to use life-prolonging pharmacologic care at EOL even at the cost of feeling worse.(63)

Two studies with moderate risk of bias explored individuals’ health literacy. One showed that trust in healthcare and health literacy did not explain disparities in preferences for life-prolonging pharmacologic care,(63) while another showed that health literacy partially explained the relationship between race and knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), which may affect EOL care decisions.(64) Three studies with moderate to high risk of bias explored patient and caregiver knowledge. One study with moderate risk of bias found increased beliefs that hospice must be received in a facility and that it is reserved for those who will only live a few days among Black patients, which could lead to lower uptake of hospice services.(48) One found that Black family caregivers had a lower level of knowledge about dementia compared with white family caregivers of patients with dementia, which could influence outcomes,(49) while another found that awareness that death was imminent decreased in-hospital death in white but not Black patients, suggesting that increased knowledge of prognosis alone will not reduce disparities in location of death.(65)

One study with moderate risk of bias considered individuals’ health care resources and showed that in addition to functional status, having health insurance was associated with increased willingness to consider hospice services.(41)

Ten studies focused on the interpersonal level of influence. Several examined the role of palliative care. One study with moderate risk of bias found that inpatient palliative care consultation decreased racial disparities in advance directive completion.(12) However, two studies revealed shortcomings of communication by palliative care teams. One with moderate risk of bias showed fewer conversations with Black patients included prognostic information compared with those with white patients,(66) while another with low risk of bias showed that palliative care clinicians overestimate survival for Black patients, leading to decreased hospice use.(67)

Communication between clinicians and patients and families were the focus of several studies. Some highlighted the importance of communication from healthcare providers. Even without palliative specialists, one randomized controlled trial with low risk of bias found that having an advance care planning session with a healthcare provider increased advance directive completion among Black patients and reduced disparities.(58) The importance of initiation of advance care planning by health care providers was supported by a study with low risk of bias which showed that perceived norms among family, friends and physicians that set expectations for advance care planning explained variance in intention to engage in advance care planning.(68) In another study with moderate risk of bias, higher quality of communication with health care providers decreased decisional conflict reported by bereaved Black family members.(69)

Other studies did not show positive effects of communication. When looking at health care utilization outcomes, one study with low risk of bias found that quality of health care provider communication did not explain racial differences in hospice or emergency room use at EOL.(70) A study with high risk of bias found that having a health care proxy or EOL discussion increased patient emotional distress as reported by caregiver among Black patients.(71) Health care provider behavior may explain this finding. One randomized controlled trial with low risk of bias showed that physicians exhibit more closed nonverbal communication behaviors when discussing goals of care for a critically and terminally ill Black compared with white standardized patient, which could increase the emotional distress of such communication.(59) On the other hand, one study with low risk of bias found that perceived discrimination and mistrust in healthcare did not explain differences between Black and white patients in advance directive completion.(72)

Sixteen studies examined the community level of influence. Embedding an advance care planning session with a healthcare provider in the community setting increased advance directive completion among Black patients.(58) Other studies looked at the role of community availability of services as a driver of disparities in EOL care. One study with low risk of bias found that counties with increased hospital beds and fewer general practitioners had greater racial disparities in hospice use.(73) Two studies with low risk of bias showed that receipt of care in minority-serving hospitals decreased the odds of receiving palliative care.(74)(75) Palliative care availability was linked to outcomes in a study with high risk of bias which found that palliative care availability in the hospital increased the rate of do-not-resuscitate orders among Black patients.(76)

Two of the sixteen raised issues of equity in quality of hospice care. One with moderate risk of bias showed that the greater the proportion of Black patients served by hospice agencies, the more frequently families reported concerns about quality and coordination of care.(77) Another study with low risk of bias found that Black patients received fewer visits from hospice staff in the last 2 days of life compared with whites.(78)

Several studies looked at practice patterns at the community level. There is some evidence that segregation of minority patients into particular institutions and networks contributes to disparities. One study with low risk of bias found that a measure of healthcare racial segregation correlated with more aggressive EOL care and less hospice use in Black patients, while another study with moderate risk of bias found that larger proportions of Black residents in nursing homes were associated with increased odds of in-hospital death and decreased hospice use.(79)(80) The effect of community practice patterns was inconsistent. A study with low risk of bias did not find a correlation between regional practice patterns and intensity of EOL care for Black patients.(81) However, a study with moderate risk of bias found that receipt of care specifically in a provider-based research network practice increased hospice enrollment among Black patients compared with receipt of care in community practices or academic medical centers.(82) Finally, prevalence of business models within a community may be important. One study with moderate risk of bias found that greater prevalence of for-profit hospices in a region was associated with increased use of hospice among racial minorities.(83)

Four of the sixteen studies, all with low risk of bias, examined both the community and societal level of influence. They found that geographic variation and practice patterns in minority-serving health care institutions contributed to disparities.(84)(85) Findings related to hospice-level variation were mixed. One study found that hospice-level variation in intensity of EOL care did not explain racial differences in hospitalization at EOL,(86) while another study with moderate risk of bias found that Black patients reported higher quality of care within the same hospice compared with whites, but across hospices Black patients reported lower quality suggesting that lower quality hospice organizations explained the overall disparity.(87)

Types of studies

The majority of studies were cross-sectional. There were three prospective cohort studies, six retrospective cohort studies and three randomized controlled trials.

Outcome measures

We searched for studies with outcomes including type of EOL care delivered, processes of care (e.g. palliative care consult), symptom management, advance care planning or patient/family ratings of quality of EOL care. The majority of the studies we found measured advance care planning and type of care delivered.

Study Quality

Most of the studies had some elements that raise concerns about risk of bias. Very few reported blinding procedures, many were underpowered or did not report power analyses, and a substantial number did not adequately control for confounders (Appendix 3 & 4).

Discussion

At this junction it is critical for the palliative care research community to consider how we can move forward to address structural, institutional and interpersonal racism to reduce EOL disparities for Black patients. This review found that researchers have made inroads into addressing structural inequities such as distribution and quality of medical services in communities. In fact, in the domain of Health Care Systems, the attention of researchers has been fairly equally distributed among the individual, interpersonal and community level of influence. This finding is encouraging and contrasts with the finding from the general health disparities literature that much research remains at the individual level of influence. More work remains to be done, however. In particular, the sociocultural environment, physical/built environment, behavioral and biological domains remain understudied.(88) In the healthcare domain, the societal level of influence (e.g. health policy and law) remain understudied. In the sociocultural domain, the majority of the studies still focused on the individual level of influence, missing key areas of research in interpersonal discrimination and local and societal structural discrimination.

In qualitative studies, patients have identified financial issues, health insurance, health systems barriers and communication with providers are key drivers of racial disparities in EOL care. Although beyond the scope of this paper, using the NIMHD framework to systematically review the qualitative literature could highlight overlooked areas in quantitative analyses and identify promising areas for future research. In the sociocultural environment, interpersonal discrimination and individuals’ response to discrimination both within and outside of the health care environment may profoundly affect both the type and quality of EOL care. In particular, the role of racism towards family caregivers and its effect on both EOL decision-making and family functioning during the EOL period should be investigated. In the physical or built environment, factors such as limited transportation options, cramped living spaces or unsafe neighborhoods may inhibit access to palliative care and limit hospice options. In the behavioral domain, national and local policies such as concurrent hospice could be evaluated for their effects on reducing or exacerbating disparities. Finally, most studies of EOL disparities control for biological factors such as age, type of terminal illness and comorbid conditions. However, the enormous racial disparities in COVID-19 illustrated how a community’s experience with a particular disease state may profoundly affect the lived experience at EOL. Furthermore, the burden of illness across the lifespan and earlier age of illness may be important considerations for how communities conceptualize the EOL period.

Studies exploring the individual level of influence tended to be of poorer quality with higher risk of bias, making conclusions about the role of Black patients’ characteristics and beliefs in disparities premature. The majority of the studies included in this review are cross-sectional. This research strategy for examining causal mechanisms is inherently limited in that the Bradford Hill criteria of temporality cannot be established.(89) Future studies should evaluate the effects of interventions in controlled trials on reducing or exacerbating EOL disparities.

Many of these studies focused on intermediate outcomes, such as advance care planning, and proxy outcomes for quality of EOL care such as ICU use, hospitalization and hospice enrollment. Future studies should focus on patient-centered outcomes such as goal-concordant care and patient- and family-reported quality of EOL care and satisfaction.

Fully 179 of the studies retrieved in our search (including 3 by the first author of this paper) were excluded because they merely documented disparities without exploring or addressing causal mechanisms. While it is temptingly easy to analyze large datasets by race and ethnicity, several decades of documentation of disparities has not improved outcomes for Black patients. It is time to move forward and build a research program that can help clinicians and systems reduce disparities.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we limited this search to CINAHL, PubMed and PsychInfo. Other databases, including social work databases might yield more studies in different domains given the different focus of other disciplines. Categorization of studies was sometimes difficult and subjective. We used two independent reviewers to minimize bias in categorization and evaluation of bias.

In sum, this review provides important information regarding the scope of the literature on disparities in EOL care for Black patients and their families. The NIMHD framework shows a spectrum of domains and levels of influence to explore mechanisms for disparities. Researchers can use this framework to paint a more complete picture of causes and address interpersonal, institutional and systemic racism in the future.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure Statement:

The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose. Dr. Chuang receives funding from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities 5K23MD015277-02.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Chuang, Department of Family and Social Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 3347 Steuben Avenue, 2nd Floor, Bronx, NY 10467.

Sandra Yu, Columbia Mailman School of public Health.

Annette Georgia, New York University.

Jessica Nymeyer, Calvary Hospital.

Jessica Williams, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

References:

- 1.Frahm KA, Brown LM, Hyer K. Racial disparities in receipt of hospice services among nursing home residents. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr D Racial differences in end-of-life planning: why don’t Blacks and Latinos prepare for the inevitable? Omega (Westport) 2011;63:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Degenholtz HB, Arnold RA, Meisel A, Lave JR. Persistence of Racial Disparities in Advance Care Plan Documents Among Nursing Home Residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2002;50:378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrido MM, Harrington ST, Prigerson HG. End-of-Life Treatment Preferences: A Key to Reducing Ethnic/Racial Disparities in Advance Care Planning? Cancer 2014;120:2981–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, Danis M. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:651–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang IA, Neuhaus JM, Chiong W. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Advance Directive Possession: Role of Demographic Factors, Religious Affiliation, and Personal Health Values in a National Survey of Older Adults. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2016;19:149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yancu CN, Farmer DF, Leahman D. Barriers to hospice use and palliative care services use by African American adults. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 2005;45:634–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phipps E, True G, Harris D, et al. Approaching the end of life: attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of African-American and white patients and their family caregivers. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahaney-Price AF, Hilgeman MM, Davis LL, et al. Living will status and desire for living will help among rural Alabama veterans. Res Nurs Health 2014;37:379–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: impact of terminal illness acknowledgment, religiousness, and treatment preferences. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaide GB, Pekmezaris R, Nouryan CN, et al. Ethnicity, race, and advance directives in an inpatient palliative care consultation service. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du XL, Parikh RC, Lairson DR. Racial and geographic disparities in the patterns of care and costs at the end of life for patients with lung cancer in 2007–2010 after the 2006 introduction of bevacizumab. Lung Cancer 2015;90:442–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdollah F, Sammon JD, Majumder K, et al. Racial Disparities in End-of-Life Care Among Patients With Prostate Cancer: A Population-Based Study. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13:1131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi HA, Fernandez A, Jeon SB, et al. Ethnic disparities in end-of-life care after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2015;22:423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nayar P, Qiu F, Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Disparities in end of life care for elderly lung cancer patients. J Community Health 2014;39:1012–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connor SR, Elwert F, Spence C, Christakis NA. Racial disparity in hospice use in the United States in 2002. Palliat Med 2008;22:205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Check DK, Samuel CA, Rosenstein DL, Dusetzina SB. Investigation of Racial Disparities in Early Supportive Medication Use and End-of-Life Care Among Medicare Beneficiaries With Stage IV Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatia M, Payne R, Tulsky JA. Race and Residence: Intercounty Variation in Black-White Differences in Hospice Use. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2013;46:epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor JS, Rajan SS, Zhang N, et al. End-of-Life Racial and Ethnic Disparities Among Patients With Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1829–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JJ, Long AC, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA. The Influence of Race/Ethnicity and Education on Family Ratings of the Quality of Dying in the ICU. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson KS. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2013;16:1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-Life Care in Black and White: Race Matters for Medical Care of Dying Patients and their Families. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2005;53:1145–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith AK, McCarthy EP, Paulk E, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Advance Care Planning Among Patients With Cancer: Impact of Terminal Illness Acknowlegment, Riligiousness, and Treatment Preferences. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008;26:4131–4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med 2008;11:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1953–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen RS, Allen JY, Hilgeman MM, DeCoster J. End-of-life decision-making, decisional conflict, and enhanced information: race effects. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1904–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fishman J, O’Dwyer P, Lu HL, et al. Race, treatment preferences, and hospice enrollment: eligibility criteria may exclude patients with the greatest needs for care. Cancer 2009;115:689–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Soc Sci Med 1999;48:1779–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5559–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On Racism: A New Standard for Publishing on Racial Healht Inequities. In: Health Affairs Blog, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardeman RR, Karbeah J. Examining racism in health services research: A disciplinary self-critique. Health Serv Res 2020;55 Suppl 2:777–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvidrez J, Castille D, Laude-Sharp M, Rosario A, Tabor D. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework. Am J Public Health 2019;109:S16–s20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Inpatient Palliative Care Consultation for Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3802–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen MT, Feeney T, Kim C, et al. Patient-Level Factors Influencing Palliative Care Consultation at a Safety-Net Urban Hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020:1049909120981764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Williams RB, Hilliard TS, Dilworth-Anderson P. Associations of social support and 8-year follow-up depressive symptoms: Differences in African American and White caregivers. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health 2012;35:289–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekhet AK. Resourcefulness in African American and Caucasian American caregivers of persons with dementia: Associations with perceived burden, depression, anxiety, positive cognitions, and psychological well‐being. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2015;51:285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eneanya ND, Wenger JB, Waite K, et al. Racial Disparities in End-of-Life Communication and Preferences among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Am J Nephrol 2016;44:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kahana E, Kahana B, Bhatta T, et al. Racial differences in future care planning in late life. Ethn Health 2020;25:625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell MM, Hansen ED, Tseng TY, et al. Correlates of Patterns of Health Values of African Americans Living With HIV/AIDS: Implications for Advance Care Planning and HIV Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park NS, Jang Y, Ko JE, Chiriboga DA. Factors Affecting Willingness to Use Hospice in Racially/Ethnically Diverse Older Men and Women. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwak J, Ellis JL. Factors related to advance care planning among older African American women: Age, medication, and acute care visits. Palliat Support Care 2020;18:413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang IA, Neuhaus JM, Chiong W. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Advance Directive Possession: Role of Demographic Factors, Religious Affiliation, and Personal Health Values in a National Survey of Older Adults. J Palliat Med 2016;19:149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cruz-Oliver DM, Tseng TY, Mitchell MM, et al. Support Network Factors Associated With Naming a Health Care Decision-Maker and Talking About Advance Care Planning Among People Living With HIV. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:1040–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noh H, Kim J, Sims OT, Ji S, Sawyer P. Racial Differences in Associations of Perceived Health and Social and Physical Activities With Advance Care Planning, End-of-Life Concerns, and Hospice Knowledge. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silveira MJ, Connor SR, Goold SD, McMahon LF, Feudtner C. Community supply of hospice: does wealth play a role? J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;42:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abbas A, Madison Hyer J, Pawlik TM. Race/Ethnicity and County-Level Social Vulnerability Impact Hospice Utilization Among Patients Undergoing Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:1918–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jonnalagadda S, Lin JJ, Nelson JE, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in beliefs about lung cancer care. Chest 2012;142:1251–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettigrew C, Brichko R, Black B, et al. Attitudes toward advance care planning among persons with dementia and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr 2019:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ko E, Lee J. End-of-life treatment preference among low-income older adults: a race/ethnicity comparison study. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:1021–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koss CS. Does Religiosity Account for Lower Rates of Advance Care Planning by Older African Americans? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2018;73:687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonner GJ, Freels S, Ferrans C, et al. Advance Care Planning for African American Caregivers of Relatives With Dementias: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38:547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Racial Carr D. and ethnic differences in advance care planning: identifying subgroup patterns and obstacles. J Aging Health 2012;24:923–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bazargan M, Cobb S, Assari S. Completion of advance directives among African Americans and Whites adults. Patient Educ Couns 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Byhoff E, Harris JA, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Racial and Ethnic Differences in End-of-Life Medicare Expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:1789–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang AY, Zyzanski SJ, Siminoff LA. Ethnic differences in the caregiver’s attitudes and preferences about the treatment and care of advanced lung cancer patients. Psychooncology 2012;21:1250–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Conner NE. Predictive factors of hospice use among Blacks: applying Andersen’s Behavioral Model. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:368–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyon ME, Squires L, D’Angelo LJ, et al. FAmily-CEntered (FACE) Advance Care Planning Among African-American and Non-African-American Adults Living With HIV in Washington, DC: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Documentation and Health Equity. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:607–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elliott AM, Alexander SC, Mescher CA, Mohan D, Barnato AE. Differences in Physicians’ Verbal and Nonverbal Communication With Black and White Patients at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koss CS, Baker TA. Where There’s a Will: The Link Between Estate Planning and Disparities in Advance Care Planning by White and Black Older Adults. Res Aging 2018;40:281–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fishman JM, Ten Have T, Casarett D. Is public communication about end-of-life care helping to inform all? Cancer news coverage in African American versus mainstream media. Cancer 2012;118:2157–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yeager KA, Williams B, Bai J, et al. Factors Related to Adherence to Opioids in Black Patients With Cancer Pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyce-Fappiano D, Liao K, Miller C, et al. Preferences for More Aggressive End-of-life Pharmacologic Care Among Racial Minorities in a Large Population-Based Cohort of Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eneanya ND, Olaniran K, Xu D, et al. Health Literacy Mediates Racial Disparities in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Knowledge among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018;29:1069–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Romo RD, Cenzer IS, Williams BA, Smith AK. Relationship between expectation of death and location of death varies by race/ethnicity. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 2018;35:1323–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ingersoll LT, Alexander SC, Priest J, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in prognosis communication during initial inpatient palliative care consultations among people with advanced cancer. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gramling R, Gajary-Coots E, Cimino J, et al. Palliative Care Clinician Overestimation of Survival in Advanced Cancer: Disparities and Association With End-of-Life Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McAfee CA, Jordan TR, Sheu JJ, Dake JA, Kopp Miller BA. Predicting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Advance Care Planning Using the Integrated Behavioral Model. Omega (Westport) 2017:30222817691286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith-Howell ER, Hickman SE, Meghani SH, Perkins SM, Rawl SM. End-of-Life Decision Making and Communication of Bereaved Family Members of African Americans with Serious Illness. J Palliat Med 2016;19:174–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Samuel-Ryals CA, Mbah OM, Hinton SP, et al. Evaluating the Contribution of Patient-Provider Communication and Cancer Diagnosis to Racial Disparities in End-of-Life Care Among Medicare Beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luth EA, Prigerson HG. Unintended harm? Race differences in the relationship between advance care planning and psychological distress at the end of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2018;56:752–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koss CS, Baker TA. A Question of Trust: Does Mistrust or Perceived Discrimination Account for Race Disparities in Advance Directive Completion? Innov Aging 2017;1:igx017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Payne R, Tulsky JA. Race and residence: intercounty variation in black-white differences in hospice use. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cole AP, Nguyen D-D, Meirkhanov A, et al. Association of Care at Minority-Serving vs Non–Minority-Serving Hospitals With Use of Palliative Care Among Racial/Ethnic Minorities With Metastatic Cancer in the United States. JAMA Network Open 2019;2:e187633–e187633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Faigle R, Ziai WC, Urrutia VC, Cooper LA, Gottesman RF. Racial Differences in Palliative Care Use After Stroke in Majority-White, Minority-Serving, and Racially Integrated U.S. Hospitals. Crit Care Med 2017;45:2046–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sacco J, Deravin Carr DR, Viola D. The effects of the Palliative Medicine Consultation on the DNR status of African Americans in a safety-net hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013;30:363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rhodes RL, Xuan L, Halm EA. African American bereaved family members’ perceptions of hospice quality: do hospices with high proportions of African Americans do better? J Palliat Med 2012;15:1137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teno JM, Plotzke M, Christian T, Gozalo P. Examining Variation in Hospice Visits by Professional Staff in the Last 2 Days of Life. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zheng NT, Mukamel DB, Caprio T, Cai S, Temkin-Greener H. Racial disparities in in-hospital death and hospice use among nursing home residents at the end of life. Med Care 2011;49:992–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Austin AM, Carmichael DQ, Bynum JPW, Skinner JS. Measuring racial segregation in health system networks using the dissimilarity index. Soc Sci Med 2019;240:112570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang SY, Hsu SH, Aldridge MD, Cherlin E, Bradley E. Racial Differences in Health Care Transitions and Hospice Use at the End of Life. J Palliat Med 2019;22:619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Penn DC, Stitzenberg KB, Cobran EK, Godley PA. Provider-based research networks demonstrate greater hospice use for minority patients with lung cancer. J Oncol Pract 2014;10:e182–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hughes MC, Vernon E. Closing the Gap in Hospice Utilization for the Minority Medicare Population. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2019;5:2333721419855667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karanth S, Rajan SS, Revere FL, Sharma G. Factors Affecting Racial Disparities in End-of-Life Care Costs Among Lung Cancer Patients: A SEER-Medicare-based Study. Am J Clin Oncol 2019;42:143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barnato AE, Chang CH, Lave JR, Angus DC. The Paradox of End-of-Life Hospital Treatment Intensity among Black Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Palliat Med 2018;21:69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rizzuto J, Aldridge MD. Racial Disparities in Hospice Outcomes: A Race or Hospice-Level Effect? J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Price RA, Parast L, Haas A, Teno JM, Elliott MN. Black And Hispanic Patients Receive Hospice Care Similar To That Of White Patients When In The Same Hospices. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Umaretiya PJ, Wolfe J, Bona K. Naming the Problem: A Structural Racism Framework to Examine Disparities in Palliative Care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hill AB. THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION? Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.