Abstract

Objectives

explore thoughts and feelings of children on COVID-19, find out how they cope, and what they did during lockdown. It was total lockdown in Luzon, Philippines, April 2020 – when survey was conducted; pre-tested open-end questionnaire was administered to children who answered either by paper and pen, or through social media, with parents’ cooperation.

Participants

200 boys and girls, 6-12 years old, public and private schools in NCR-Luzon.

Results

Participants heard COVID-19, pandemic and lock down from media and family; described as deadly, dangerous, contagious, world-wide, death-causing virus; about 90% expressed sadness, fear, boredom, anger, disappointments and difficult time; employed self-enhanced coping mechanisms, and engaged in hobbies and interests to assuage thoughts and feelings; family appeared as saving grace.

Recommendations: develop strategies to assist children during critical events; studies – find out effects of pandemic on participants’ health; visit participants after two years to find out reminiscence of pandemic experience.

Keywords: COVID-19, lock down, pandemic, Filipino, family

In a life time, individuals in different parts of the world have experienced, witnessed and testified on the various natural calamities and disasters which have claimed lives and wrecked properties that occurred at various times of the year, or at different seasons. But this decade, except perhaps in isolated places, peoples of planet earth are witnessing, experiencing and documenting the one and only disaster that is confronting almost every one, everywhere at one time and perhaps, one of the longest durations – the deadly coronavirus disease, now known as COVID-19 (Tedros, 2020). It was estimated that mortality figures globally may be around the 50 million level (British Medical Journal, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). In the Philippines, people in the different regions continue to be victims of natural calamities, like the destructive typhoons where strong rains, violent winds and drowning floods, and volcanic eruptions, have become part of the Filipino life. However, COVID-19 is a tragic disaster that is not only new but which the people are very much unprepared to confront with.

In an unprecedented turn, from epidemic to pandemic, the Philippines together with the world woke up to an invisible enemy that suddenly everything was put to a halt: economically, small industries to huge corporate businesses ceased operations; people are socially-distanced; all kinds of offices and institutions were closed; worshipers attend online services; countries, states, provinces, and communities were locked down.

People who are ever busy with daily concerns found themselves locked in their homes. It was one of those moments that we found a common interest, and conceptualized a study on how children are affected by the pandemic.

There were attempts to search for studies on Filipino children’s emotions during disasters and calamities but due to time constraints and in our desire to grab the opportune time to conduct this study, the hunt was not really exhaustive.

It appeared that many studies conducted on corona virus and children are mostly focused on health concerns particularly in the infant stage however, we selected online articles on the issues which are somehow related to our topic. One is the multinational, multicenter cohort study of COVID-19 and children, although focused on service planning and allocation of resources, children’s health condition (18 years and younger) were discussed since they are the benefactors of the services. Riphagen et al. (2020) found an unprecedented cluster of eight children (8 to 14 years) with hyperinflammatory shock which formed the basis of a national alert for a huge number of children to undergo test for corona virus.

Adigun (2020) reported that COVID-19 disease in children is usually mild, fatalities rare as UK study says; that children are not as adversely affected by COVID-19 as adults. However, it did not mention of the possible negative effects of the virus on the children’s mental, emotional, and psychological health, and the consequences in their later childhood life.

Going a little back, the research brief on ‘The Impact of Natural Disaster on Childhood Education’ looked at devastating earthquakes’ effect on young people in Nepal reported that children around the world react similarly to disasters despite differences in cultures and resources (Crowder, 2016). Strauss (2017) pointed out, that based on research, children who were victims of disasters can suffer from trauma and bereavement far longer than adults realize, and this can affect not only how well they perform at school but also the trajectory of their lives. The study of Gibbs et al. (2019) showed that social disruption caused by natural disasters often interrupts educational opportunities for children but little is known about children's learning in the following years, their findings highlight the importance of building and maintaining supportive relationships following a disaster. Ramchandani (2020) expressed his view that the direct impact of COVID-19 on children seems to be less severe than on adults but indirect and hidden consequences will have a lasting effect on children's education, social life and physical and mental health.

Wang (2020) showed how to support children (and families) during quarantine to reduce the risk of negative mental health. The initial findings of a study involving young children (ages four to 10) suggest that they are worried about family and friends catching the virus; afraid to leave their homes and are worried there will not be enough food to eat; and over a one-month period in lockdown parents/carers reported that they saw increases in their child’s emotional difficulties, such as feeling unhappy, worried, being clingy and experiencing physical symptoms associated with worry (Pearcey et al., 2020).

We may not be aware, or know much about what the concept of threat of the current pandemic brings or means to a school-age child who have never experienced a dreadful event. This is our most important concern and interest which motivated us to pursue this study during the lockdown period. We thought that it is best at this time to explore what are their unspoken sentiments when the invisible COVID-19 is at its height in its attack against anyone. We envision that we can help mollify some of the negative effects of COVID-19 on young children when we know their thoughts and feelings, and what they do during lockdown. The image of the Filipino child in an uncharted environmental condition, guided and inspired us to answer the following objectives:

To explore the thoughts and feelings of children about COVID-19,

To find out how they cope with the pandemic, and

To know what they did during the lockdown

Methodology

Research Design

This is a descriptive survey which employed a pre-tested open-end questionnaire and used a non-standardized measurement.

Sampling Method

Due to the total lockdown brought about by COVID-19 pandemic, the study utilized the purposive sampling technique. Parents or guardians known to the researchers were contacted through the cell phone, or email, and requested for their children who met the criteria, to be a participant to the study. The sampling method was constrained by unavailability of resources like contacting more parents who may not have access to the social media; the parents’ inaccessibility to the gadget to print the questionnaires; a place to administer the questionnaire such as in a classroom or a private place; and for us, the researchers, to administer the questionnaire to the participants.

Participants

Parents or guardians who consented to have their children who met the criteria – in school, ages 6-12 years old – signed up using email, or cell phone (some questionnaires were sent through Messenger as requested by parents). The online google research form method was a last recourse when the paper and pencil technique was found problematic by parents who reported difficulty in producing the printed questionnaire for lack of printers in their home.

Instrument

An open-ended questionnaire which included a page for participants’ age, gender, grade level and school type, was pre-tested to 20 children whose characteristics were similar to intended participants to the study. In the final questionnaire, added were the participants’ nickname and birthdate for encoding.

The final questionnaire consisted of 11 open-end items on the issues: COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown.

A separate page addressed to the parent or guardian requesting for their comments was added as the last page of the questionnaire.

Procedure

Data-gathering method was through the aforesaid media. The questionnaire with a letter to the parent/guardian explained the purpose of the study, and asked consent for their child’s participation in the study. Parents were given the questionnaire, through email or cell phone, where the child answered on it directly, or they supervised the youngest participants when needed, and returned this questionnaire to the researcher through the same media. However, when some parents reported that they don’t have the appropriate gadget to print the questionnaire, the google online tools for research was similarly sent to parents. Fielding out the questionnaires started in mid-April, when Luzon, (Philippines) including the National Capital Region (NCR), were in complete lockdown; it ended in June, 2020 when partial lock down in the same place was lifted.

Results

Simple descriptive statistics was used in reporting the data, mostly in graphic presentations. Since non-standardized measurement was used, the processes involved were adapted from literature selecting only what were deemed appropriate with the data, without a specific reference of source. Data were analyzed through the following processes:

Analysis of Data

The questionnaire from the 200 participants generated about 22,000 raw data in words, (and few numbers).

These words were the participants’ expressions or descriptions of their knowledge, thoughts and feelings about the issues – COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown; how they handled or managed themselves during the lockdown, and the activities they did, and missed, or wished to do more with family. They also stated the communication media in their home.

Categorization and Coding of Responses

The expressions of participants on the issues were categorized according to similarity or relativity of concepts, terms, ideas or clues including Pilipino words which were not translated, these are presented in italics. Coding used, or putting the labels, was based on the main concepts found, such as about the self (participant), family events or affairs, and the participants’ different thoughts, feelings, concerns, and activities. A cluster of codes for a particular concept, say the coping mechanisms and some activities of participants, were found to be interrelated. These were compared between and within cases; terms which appeared almost the same in their concept or meaning were grouped together under one theme.

Developing Themes

Some themes, from a cluster of several codes, emerged in the initial tryout; finding the last themes although time consuming and quite resource-intensive, was achieved. After similar or related terms were coded, reviewed and clustered, which were likewise repeatedly analyzed and branded, four conclusive themes finally emerged.

Thematic Analysis

This last process was employed to capture the most important sentiments of participants thus, giving a clearer picture of their thoughts and feelings. These are: Theme 1 – Inward and Outward Fear and Sadness; Theme 2 – Mixed Positive and Negative Emotions About Lockdown; Theme 3 – Hope and Faith in God Expressed in Prayer; and Theme 4 – Family as a Stronghold of Support.

Graphic Presentations

There were multiple answers to individual issues hence, for brevity key words and phrases were categorized and presented in tables and figures.

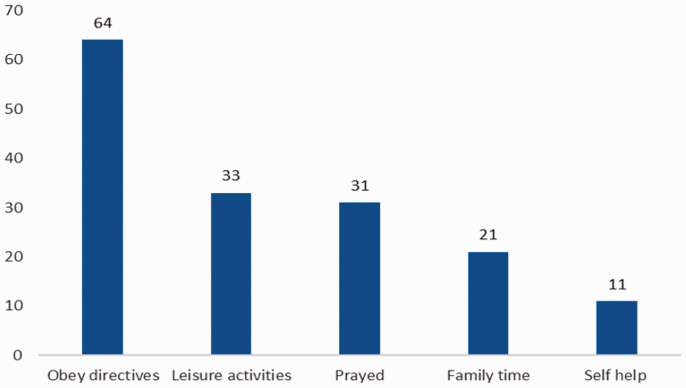

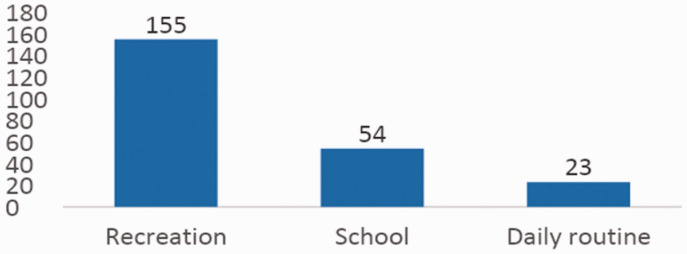

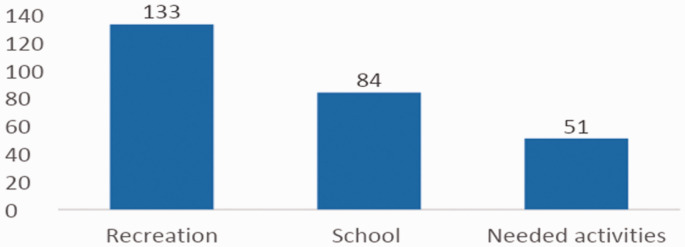

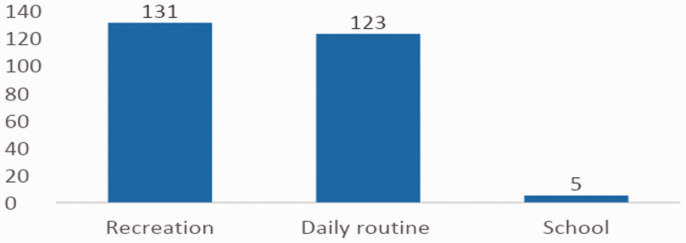

Table 1 shows the demographic data of participants; Table 2 reflects what they said about the issues: COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown; Table 3 reveals their thoughts and feelings about these issues; Table 4 contains the comments from the participants’ parents or guardians; and Table 5 presents the sources of information resources used by participants at home. Figure 1 demonstrates the participants’ coping behavior during lockdown; Figure 2 reflects the activities that participants did during lockdown; Figure 3 reveals what participants missed while confined at home; and Figure 4 shows what participants wished to do more with family while in lockdown.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 200).

| Characteristics | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 93 | 46 |

| Female | 107 | 54 |

| Age/years | ||

| 6 | 24 | 12 |

| 7 | 19 | 9 |

| 8 | 31 | 16 |

| 9 | 34 | 17 |

| 10 | 38 | 19 |

| 11 | 34 | 17 |

| 12 | 20 | 10 |

| School type | ||

| Public | 90 | 45 |

| Private | 110 | 55 |

| Grade level | ||

| 1 | 29 | 14 |

| 2 | 13 | 6 |

| 3 | 41 | 21 |

| 4 | 32 | 16 |

| 5 | 44 | 22 |

| 6 | 37 | 19 |

| 7 | 4 | 2 |

Table 2.

Participants’ Response to the Item, ‘What Can You Say About COVID-19, Pandemic and Lockdown/Quarantine’ (N=200).

| Description* | F |

|---|---|

| On COVID-19 | |

| Deadly, contagious, nakakamatay, dangerous virus, death | 111 |

| Scary | 23 |

| Bad | 8 |

| Other responses: it kills your body; you cannot go outside; an invisible enemy that cause death | |

| On pandemic | |

| Deadly, dangerous, contagious, global, world-wide virus | 64 |

| Fearful, terrifying, scary | 18 |

| Don’t know, not sure | 10 |

| No answer | 15 |

| Other responses: | |

| Bad (4); sickness (4); pneumonia (3); worried (2); worst (2); alarming(2) disturbing; irritating; all taking about it; | |

| On lockdown or quarantine | |

| Do don’t go out, good, for protection | 90 |

| Angry, annoying, bad, boring, depressing, dull, hassle, hate, | |

| Horrible, irritating, lonely, menacing, sad, scared | 35 |

| Government | 16 |

| Control virus | 4 |

| Don’t know, not sure | 15 |

| Other responses: Did not enjoy my vacation; no transportation; nakakatuwa kasi prinotektahan tayo ni Duterte; the negative effect on people; scared and unhappy; sad and scared; worried and scared; sad and nervous; scared and terrified; disappointed and sad; boring and annoying |

Table 3.

Thoughts and Feelings of Participants on COVID-19, Pandemic and Lockdown/Quarantine (N=200).

| Description* | f |

|---|---|

| On COVID-19 | |

| Deadly, contagious, nakakamatay, dangerous virus, inevitable, horrible/scary | 51 |

| Bad | 18 |

| Don’t know | 12 |

| Other responses: to get rid of it asap; it can infect 1/6 of the world; nagugulo na ang mundo; | |

| On pandemic | |

| Deadly, dangerous, contagious, global, world-wide, cause death fearful, terrifying, scary disease/virus | 25 |

| Malungkot at nakakulong | 19 |

| Bad. | 18 |

| Can’t play with my friends; can’t go to other places; can’t go anywhere; can’t go out; can't play outside | 16 |

| Sickness | 13 |

| Miss mall/going out, my friends/going to school | 4 |

| Don’t know, not sure | 14 |

| Other responses: worried (2); worst (2); delubyo (2); disturbing; alarming; in danger; it is growing and Trump is not helping; naiisip ko po ay baka po maubos na ang mga tao dito sa Pilipinas; nagugulo na ang mundo | |

| On lockdown or quarantine | |

| It means locked, trapped, nakakulong | 116 |

| Feeling safe | 18 |

| Feeling bored/bored and sad; boring and annoying | 16/2 |

| Obey government guidelines (keep distance, wash hands, wear mask) I/we/people can’t go outside of my/our/their home happy, good | 11 |

| Other responses: worried and sad; more playing time; stressed; ang tagal ng lock down; no gadgets what should I do? no work no pay; kasi po walang magawa dito sa loob ng bahay; prevents people from meeting; naiinip sa bahay; mananahimik po sa bahay; helping Mother Earth. | 6 |

Table 4.

Comments From Parents or Guardians of Participants.

| Commentaries* | F |

|---|---|

| Interesting and helpful, informative, relevant, timely | 14 |

| Good/glad to realize/know/hear my child’s needs/thoughts | |

| /Opinion on lockdown/current issues | 13 |

| Great/good opportunity for children to share/express their thoughts | |

| /Feelings/opinion about the pandemic/covid | 6 |

| Amazing, great, nice, safe, masaya, maganda | 6 |

| Helps my child to become vocal /express feelings | |

| /Thoughts | |

| About pandemic | 4 |

| Okay, good, very good | 3 |

| Gained insights on child’s thoughts on pandemic | 3 |

| Good that my child shared feelings/insights about lockdown | 3 |

| Questionnaire is long/quite long/very long | 3 |

Table 5.

Participants’ Sources of Information.

| Sources of information | F |

|---|---|

| Mass media | |

| TV, radio, print, computer, etc. | 135 |

| Family and relatives | 129 |

| School | 9 |

| Friends, doctor | 6 |

Figure 1.

Coping Mechanisms of Participants.

Figure 2.

Activities of Participants During Lockdown/Quarantine.

Figure 3.

Activities Participants Wished to Do More Together With Their.

Figure 4.

What Participants Wished to Do More Together With Family.

Participants

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participants from the elementary schools of the public and private institutions; the private sectors included colleges and universities, both coed and exclusive.

Participants’ Thoughts and Feelings

Most of participants’ expressions were in one-word terms, phrases, or brief statements. For brevity these were edited, or deleted, among these were I and I am, it is, the, there is/are, since, due to, and because. Similarly, the brief Filipino terms are presented in italics.

Parents/Guardians and Media

Table 4 contains the edited comments from the participants’ parents or guardians. Participants’ reported that they heard and learned about the issues – COVID-19, pandemic, and lock down – from different resources as shown on Table 5.

Participants’ Coping Mechanisms

Participants employed various mechanisms to cope with COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown. Among these were: Obey government guidelines like stay at home to prevent getting infected, maghugas ng kamay at mag-alcohol, huwag na po dapat lalabas para di na magka-virus, listen to news, and support the front liners. They had leisure activities such as play with toys, games, pets, phone, gadgets, nagbabasa nalang po ako ng mga libro, and focus on hobbies. They do spiritual acts like pray not to be infected, nagpapray po para mawala ang covid, that it would end or find a solution, that it stops; and to have a normal life; lift and believe God will heal the world, and ask for His guidance, for family, kasama sila lolo at lola. They have the family and others from whom they ask questions, talk with different topics, follow their reminders and rules, or simply play with them. They play with siblings, toys, pets, and watch t.v.; occupied with hobbies with sisters and doggies, took time to hug Papa and family, stuffy toy, Tasha; talk/zoom meet with friends; spent time and call up cousins and grandparents. They also did some self-help means by keeping calm and staying positive, understanding the cause of fears, dealing with it pro-actively, trying to forget this, and not to feel sad but to be happy; made a COVID journal and wrote experiences. (Expressions of participants were edited for brevity, including Filipino words in italics.)

Participants’ Activities

Participants gave multiple responses on the item how they spend the day during lockdown which were categorized into recreation, school and daily activities. Majority of participants engaged in activities for fun, enjoyment or amusement. These included playing, watching and doing arts and crafts alone and/or together with family members, relatives and friends. Playing included the use of gadgets for video and computer games, board games, toys and even pets. Watching were television movies, programs, and news. As for arts, stated were drawing, painting, and sketching; for crafts were beads and paper folding. School-related activities included doing assignments and exercises, reading and writing. Daily routine activities like eating, sleeping, personal hygiene, grooming, praying, and (virtual) mass were mentioned. Helping in household chores such as house cleaning, and helping in the kitchen, washing clothes, watering plants, alone or with family members, were also included.

Responses of participants were likewise grouped into recreation, school and needed activities. Majority missed doing recreational past times with their family, close relatives and friends like going to the mall, beaches, parks, restaurants, and also going on vacation. Many participants also missed school activities including teachers, classmates, friends, and learning new lessons. Participants missed doing outside needed activities like buying food, walking, going to the gym, and obligatory weekly church services, with the family.

Participants wished to do more with their family were grouped into recreation, daily routine and school. Recreation for fun and amusement included watching movies, playing board games, and other leisurely activities. Mentioned daily routine activities were doing household chores such as cleaning in the house, cooking, baking, watering the plants, among others. School-related activities were reading and doing home works.

Discussion

Data clearly showed the thoughts and feelings of about 90% of participants who described their sentiments in negative, unkind and unpleasant terms, about the issues – COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown. They continue living and adjusting to the difficult condition, and expressed their varied emotions in a word, a phrase, or short narratives; employed self-made defenses; and engaged in multi-faceted activities alone or with family. Perhaps, all these behaviors and manifestations assuaged them from what may be described as a heavy emotional load for young children. Undoubtedly, the objectives of the study were strongly supported by the robust data.

The participants, confronted with daily uncharted events must have found a venue (the questionnaire) and expressed what they thought and felt about the issues (Tables 2 and 3); provided self-prescribed measures and ways probably, to remain sane and normal (Figure 1). The long, and what seems to be an indefinite duration of the lockdown, gave the participants the unplanned closer bonding with the family when they engaged in various leisure activities, hobbies and interests (Figures 2to 4).

The study which sought to find out the participants’ thoughts and feelings was achieved through an open-ended questionnaire where the responses were collated and summarized (in aforesaid Tables and Figures); and some statements were subjected to thematic analysis. The following overarching themes observed in the participants’ words created a clearer picture which captured how the participants were affected by the issues.

Theme 1 – Inward and Outward Fear and Sadness

An overarching theme that can be gathered from the responses can be worded as such: Inward and Outward Fear and Sadness. The terms ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ refer to the direction of movement of the emotions, or in other words, who these emotions are directed to – themselves or other people. These emotions are instinctive reactions to the current pandemic that the country and the world are currently facing, the younger members of our society are not spared. This is mitigated by the news of the rise of cases and deaths disseminated through multiple media – television, radio, websites, and social media (Table 5).

“Very, very sad because people all over the world get sick”

“It is terrifying and stressful. I cannot go out for a walk, cannot even buy stuff like Nintendo switch games and clothes, and new white rubber shoes for my PE class.”

Although news has a positive impact in providing people with information and updates about the pandemic, this however, has an irrefutable negative effect on the mental health of viewers, including young children. A study by the University of Oxford examining mental health found that 19% of parents said that their children were worried the family would not have enough food and other essential items during the outbreak after news coverage of panic buying and empty supermarket shelves. Piercey This can also be seen in the responses of the participants where they mention what they see or hear on the news.

“I heard it from the radio and it kills people”

“ … , I have heard a lot in the news and also on what I see people kept on disobeying the government … ”

While mass media is necessary providing updates about the pandemic, limiting the exposure of these children may be beneficial for their emotional and mental health.

Moreover, these feelings of sadness and fear may also be viewed as Inward and Outward. The inward aspect is seen among participants who are afraid or feel sad for themselves. They fear that they may contract the virus and get sick.

“I felt scared to get infected and die early.”

“I am worried because there is no cure yet.”

They also appeared to be sad because of the lockdown. While still under quarantine, these participants were not able to do the things that they used to enjoy, specifically going outside the house.

“It means kids are not allowed to leave the home.”

“ … everybody stays at home, no more malls. No more visiting other houses and going to the groceries for me.”

“It’s not nice because we cannot go out. Too boring to be at home.”

On the other hand, the outward direction is shown in participants who expressed worry for those outside of themselves, such as their family members, friends, medical workers, and those who are impoverished. This shows their concern going beyond their own safety, even beyond their own family.

“I felt sad for the people who are suffering from the virus and for the families that lost a family member and especially for the front-liners that did their very best for the people to survive from the pandemic.”

“It makes me feel worried and scared for my family and relatives, myself and the front liners and everybody in the country and the world.”

“Because a lot of people or families are suffering during ECQ, because they don’t have funds to buy all their needs to survive.”

These emotions, moving inwardly or outwardly, was also observed in children of previous studies (Pearcey et al., 2020). Needless to say, these emotions are felt by everyone who feels threatened for themselves and for others. Understandably, adults also experience these emotions – worry, anxiety, sadness, and fear, as the World Health Organization (2020) puts it:

“Children are likely to experiencing worry, anxiety and fear, and this can include the types of fears that are very similar to those experienced by adults, such as fear of dying, a fear of their relatives dying, or a dare of what it means to receive medical treatment.”

Theme 2 – Mixed Positive and Negative Emotions About Lockdown

Another theme that can be drawn from the participants’ responses, especially when asked about the lockdown, is the differences in the way that these participants feel or think about lockdown. There are participants who felt that the lockdown was an added stressor as they were unable to do the things they once did such as play outside with their friends, go out with their families, and go to school.

“It slows down everything. All of my outside activities stopped. I am stacked in the house because of the quarantined measures. It makes me sad on that part alone … ”

“This COVID-19 situation separated me physically from my friends in school, from my cousins, from the activities I normally do especially this summer break.”

However, some may conversely regard it as somewhat a blessing in disguise. They viewed the lockdown as a respite from school, an increased opportunity for play at home and time with family.

“ … but it’s really relaxing because we don’t have to go to school, and not being allowed to go to places means we can stay home more.”

“Sad and also happy it’s weird. Sad because I can’t go out and see my friends especially my cousin … happy cause I get to rest.”

More importantly, some of the participants considered the lockdown for its very essence – to prevent the spread of the virus and personal protection. Interestingly, the responses showed a realization on the part of some participants, which was probably brought about by family members and mass media, about the importance of quarantine.

“At first, I felt annoyed for having to miss out on schoolwork and time with friends. But later, I have realized how important it was to keep all of us safe, specially the front liners.”

“It is a good decision of government to suppress the increase of infection.”

“This lockdown is our government’s way of controlling the spread of virus and avoiding unnecessary deaths. Although it can sometimes be a bummer to be on lockdown, I think it is a small price to pay for safety and good health.”

“We need to obey the rules because it’s for our own protection and wellbeing.”

In summation, this theme shows that there are participants having mixed emotions about lockdown. This may not necessarily reflect the child’s values and priorities, but it may have implications in the type of support a parent or a family member can give to the child, as this support may be crucial in how their children would view the quarantine. As can be seen in their statements, the participants who knew the reason and importance of a quarantine viewed it in a more altruistic and positive way. Again, the role of family, as the children’s role model, teacher and comforter, especially during difficult times cannot be more emphasized.

Theme 3 – Hope and Faith in God Expressed in Prayer

From the responses it may be noted the repeated reference to prayer and God. The participants mentioned that prayer is a part of their daily routine – their own response to the pandemic. Some of them began praying, while others continued their prayer in increased frequency and apparent sincerity. They prayed not only for themselves, but for their families, friends, the front liners, and the rest of the world stricken with COVID. Going over their verbatim responses, many participants had the term ‘nagdadasal’, or praying to God, as an answer to the question of their reaction to the pandemic and the lockdown.

“It also helps to pray with your family and pray for God’s protection.”

“ … Praying at night to get over this crisis is always my routine before I go to bed.”

“I am not scared because I pray”.

“ … lift and believe God will heal the world.”

“I pray always to the Lord to protect me and my family and heal others who got affected by it..."

Children are regarded as the more helpless members of the family. They are very limited in terms of their capabilities, and this is especially true in this time. Parents and other adults achieve a sense of feeling useful during this pandemic by spending more time taking care of their family, buying more groceries and supplies, and donating to organizations which cater to the front liners or those who are need. These behaviors of parents may be taken by participants either positively – they become equally helpful and thoughtful- or negatively, they feel helpless and worry about not having enough and other resources, during the pandemic. Although they do social distancing, staying at home and practicing personal hygiene, participants worry and feel that they should do more. Consequently, some of these participants may have resorted to prayer as their way of helping out in this pandemic. It was perhaps that through their spirituality, some participants felt hopeful about the pandemic which would seem a dramatic change in mindset from worry and anxiety to hope for a soon-to-be brighter future for them.

“My feeling is that I’m hopeful that all of us will be able to fight the virus from spreading … ”

“My feeling is still to be hopeful and trust everyone that we can end the virus and heal a lot of people.”

Being a predominantly Catholic country, religion and spirituality plays a major role especially true during tough times in a person's life. Data shows that participants turn to prayer perhaps as a way to relieve their personal worry about themselves and others, and also making them feel hopeful.

Theme 4 – Family as a Stronghold of Support

Another theme that can be observed is the overwhelming sense of family bond and relationships. Being quarantined for months, and which may continue indefinitely, and the prohibition for senior citizens and younger children to go outside their homes have been a difficult experience for them (as can be seen in the 1st theme). However, this allows them to stay with their family members virtually every single day. This may be a downside for some participants, but for many of them, this strengthens their relationships.

“It’s a family bonding.”

“I felt happy because we get to spend time with our family but also sad becaushere are still people infected and dying because of Corona Virus.”

“I have more time with family.”

“I miss going to school and seeing my friends and doing sports but I get to stay home and spend more time with my family.”

A vital factor for this development is the oneness of the family as the family goes through this difficult time together. Their physical closeness allows the parents to keep an eye on their children, and consequently, find time to explain for participants to understand what exactly they are going through, and together. This perhaps helped the participants ease their anxiety as they understood the virus better, and as they had their family members to support them through these extraordinary circumstances.

“I always try to understand the situation or cause of my fears and worries as my parents have taught me. Fear comes from not understanding. So, the more I understand the less I fear.”

“I felt scared to get infected and die early, but after reading and studying about it with my parents I have learned to understand the virus and how to maintain a healthier lifestyle.”

Scanning through their responses, most participants mentioned obeying what their parents told them to do; while staying together during lockdown, some parents took the chance and imparted knowledge about the issues to which participants expressed appreciation. The implications for family dynamics which appeared altered by the circumstances are seemingly more favorable to both parents and their children. Although the responsibilities of parents to care for their children in these times may double, or even triple, but doing so may lead to the further strengthening of relationships fostered in the functioning of the family as one unit amidst the crisis. Needless to say, the older members of the family are crucial in the child’s physical, mental and emotional well-being and development during times when a widespread virus limits them to stay together to a great extent (Piercey et al., 2020).

The comments from parents (Table 4) should be given attention because they are the nearest, and maybe the only companion of the children during lockdown. Parents who participated in the Oxford University Study showed that after one month of lockdown, they reported an increase in their child’s emotional, behavioral and restless/attentional difficulties (Pearcey et al., 2020).

Conclusions and Recommendations

This study have achieved its objectives when participants expressed their thoughts and emotions which were mostly hurting, unkind and unfriendly. They employed self-enhanced mechanisms to cope with the pandemic, and engaged in various activities alone or with family. Positive perspectives on forging relationships with others were noted.

Generally, the participants seemed to have gained the knowledge, or perceptions, of the issues – COVID-19, pandemic and lockdown/quarantine – through the media, parents, and others. Confronted with lockdown, participants kept themselves busy with different activities, alone or with family; these somehow assuaged their fear, boredom, sadness, anger, and other negative emotions. Data seemed to indicate that adjusting to social distancing, especially when they started missing their friends, school, and places, was difficult for most participants.

It is noteworthy that strengthening family ties and relations appeared as the consoling and positive consequence of the lockdown. Participants expressed the good and wonderful remarks for their family, making the family their holding power which probably helped managed their thoughts and feelings, withstood what seemed unpleasant circumstances, and bore the challenges which confronted their young life.

This exploration was confronted with limitations: The lockdown, although it motivated this investigation, was a big constraint when participants were unavailable if compared when they are in one school or location; and the lack of control on the place where the questionnaire was filled-up by participants. It was trust on the parents/guardians that the instituted precautionary measures (such as, not coaching or helping the participant in answering the questionnaire) were followed. Our regular meeting although virtually conducted in social media would still be much friendlier and informal when face-to-face while we discussed every step of the study thus, further enhancing camaraderie.

This study may not claim to be a novel piece of work for Filipino children in this age group but we declare that it is the first of its kind that we ventured on. It is our contribution to the literature on the Filipino children’s thoughts and feelings during a difficult time, and at this stage of their growth and development.

Armed with what appeared as rich and informative data, we recommend to develop strategies to assist children at the time of, or during, a critical period or disastrous event; that the participants be revisited say, after a year or two. It would be thought-provoking and challenging to find out how they will reminisce the impact of the experience during the pandemic and how this may have affected their young heart and mind. We consider it very important the need for more studies to determine the long-term effects of the lockdown on the life of young children specifically on their mental and emotional state, the quintessence of this paper. Our recommendations are encouraged by the articles of Gibbs et al. (2019), Pearcey et al. (2020), Riphagen et al. (2020), and Strauss (2017). In addition probably, a three-generation of grandparents, parents and grandchildren may be taken as participant-companions in a study where lockdown has been enforced for say, four to six months, and find out how all were affected by the directive of staying home together, and provide support to reduce the risk of negative mental health (Wang, 2020) .

Author Biographies

Lourdes Urbano Agbing Retired, University of the Philippines and Miriam College

Josephine Dionela Agapito Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Ann Marie Albano Baradi Project Manager, Miriam College, Quezon City, Philippines; Past President, Associationof Private Schools Administrators, Quezon City

M. Bernadette Camba Guzman, RGS Program Coordinator, Welcome House Good Shepherd Sisters, Crisis Intervention Center, Manila, Philippines

Clarissa Mariano Ligon College of Education, Miriam College

Arsenia Tuazon Lozano Principal, Basic Education DepartmentNational College of Business and ArtsQuezon City, Philippines

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Lourdes Urbano Agbing https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7814-9310

References

- Adigun A. (2020, June 26). COVID-19 disease in children is usually mild, fatalities rare, UK study says. ABC News. https://app.abcnews.go.com/Health/covid-19-disease-children-mild-fatalities-rare-uk/story?id=71462424

- British Medical Journal. (2020, April 02). Covid-19: four fifths of cases are asymptomatic, China figures indicate. The BMJ.https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1375 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crowder L. (2016, April 02). Hope despite hardship. Nepal Capstone. Center on Conflict and Development. https://hardin04.wixsite.com/nepalcapstone#!about/cjg9

- Gibbs L., Nursey J., Cook J., Ireton G., Alkemade N., Roberts M., Forbes D. (2019). Delayed disaster impacts on academic performance of primary school children. Child Development, 90(4), 1402–1412. 10.1111/cdev.13200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcey S., Shum A., Waite P., Patalay P., Creswell C. (2020, June 16). Changes in children and young people’s emotional and behavioral difficulties through lockdown. Emerging Minds. https://emergingminds.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CoSPACE-Report-4-June-2020.pdf

- Ramchandani P. (2020, April 11). Children and Covid-19. New Scientist. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7194712/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Riphagen S., Gomez X., Gonzalez-Martinez C., Wilkinson N., Theocharis P. (2020). Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10237), 1607–1608. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32386565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss V. (2017, September 12). The serious and long-lasting impact of disaster on schoolchildren. Analysis. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/09/11/the-serious-and-long-lasting-impact-of-disaster-on-schoolchildren/

- Tedros. A. (2020, April 13). WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–13-april-2020

- Wang G. (2020, June 1). Seven findings that can help people deal with COVID-19. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2020/06/covid-findings

- World Health Organization. (2020, March 01). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report 41. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200301-sitrep-41-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6768306d_2