Abstract

Purpose. To evaluate medical students’ and family medicine residents’ perceptions of their current degree of nutrition training in general and regarding a whole-foods, plant-based (WFPB) diet. Methods. An original survey instrument was administered to medical students and family medicine residents. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected to evaluate perceptions of nutrition education in medical training, a WFPB diet, and ideas for nutrition-focused curricular reform. Results. Of the 668 trainees surveyed, 200 responded (response rate = 30%). Of these, 22% agreed that they received sufficient nutrition education in medical school and 41% agreed that a WFPB diet should be a focus. Respondents with personal experiences with a plant-based diet were more willing to recommend it to future patients. Common ideas for curricular reform were instruction on a WFPB diet along with other healthy dietary patterns, patient counseling, a dedicated nutrition course, and electives. Conclusions. Nutrition education in US medical training needs improvement to address the growing burden of obesity-related chronic disease. Proper nutrition and lifestyle modification should therefore play a larger role in the education of future physicians. A focus on plant-predominant diets, such as the WFPB diet, may be an acceptable and effective addition to current medical school curriculum, and deserves further study.

Keywords: medical education; nutrition education; whole-foods, plant-based diet; plant-based diet; lifestyle medicine

“Despite its lack of consistent representation in medical training, nutrition plays a significant role in the progression of chronic disease.”

The lack of adequate nutrition education in US medical schools and residency programs has been an area of concern for decades.1-14 In a survey 1 by the Nutrition in Medicine program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2010, 103 of the 109 US medical schools surveyed required some sort of nutrition education, but this averaged 19.6 hours over the course of the first 2 years of the curriculum. In the same survey, 79% of schools indicated that their students needed more nutrition education than they were currently getting. A systematic review 14 conducted nearly 10 years later found that medical students consistently perceived inadequate nutrition education in medical school and incompetence in providing nutrition care to patients. An insufficient focus on nutrition competency extends into postgraduate medical training as well. Postgraduate programs that might be expected to require training in nutrition counseling or therapy, such as family medicine or cardiology, do not have any formal nutrition-related requirements for program completion. 3 This may raise concern because physicians are often identified as nutrition experts by their patients despite feeling inadequately trained to educate their patients about proper diet.3,15 Several medical schools have developed programs to combat this lack of nutrition education11,16,17; however, a common nutrition curriculum has not been established by the governing bodies of accredited US medical schools and national medical examination organizations.10,18 A lack of recognition given to clinical nutrition by the American Board of Medical Specialties 7 and limited representation of nutrition-related content on national medical board exams 18 are contributing factors.

Despite its lack of consistent representation in medical training, nutrition plays a significant role in the progression of chronic disease. Poor diet has been addressed as the leading risk factor for mortality from chronic diseases in the United States, ranked above tobacco, alcohol, dementia, and drug use disorders. 19 From a financial standpoint, adult obese males are estimated to cost an additional $1152 of health care spending annually while adult obese females cost an additional $3613. 20 About $400 billion annually in additional health care spending can be directly attributed to largely preventable obesity-related conditions 19 based on the previous estimates. An evidence-based movement away from the typical American diet, therefore, may deserve a place at the forefront of medical education and standard practice guidelines for physicians.

Research21-27 supports a whole-foods, plant-based (WFPB) diet for the prevention and treatment of obesity and related chronic conditions. A WFPB diet is synonymous with a whole-foods vegan diet, defined as one that consists of vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, seeds, herbs, and spices and that excludes processed or refined foods and animal products. 21 Variations of this plant-based diet include the Mediterranean diet, vegan diet, and vegetarian diet, which tend to overlap in dietary research studies. For the purposes of this study, a WFPB diet refers to a vegan diet comprised predominantly of whole plant foods as defined above. A WFPB diet has been shown in the literature to ameliorate coronary artery disease, 22 improve glycemic control in type 2 diabetics,23-25 and reduce the risk of developing diabetes. 25 Those who follow a WFPB diet tend to have fewer known risk factors for cardiometabolic chronic diseases when compared to omnivores, including lower body mass index, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels, blood glucose, and blood pressure. 26 People eating vegetarian plant-based diets also have a lower rate of ischemic heart disease and cancer incidence than nonvegetarians. 27 The health-promoting effects of a plant-based diet have been demonstrated in as little as 16 days of dietary modification. 23 Given the growing body of research, an evidence-based approach to a WFPB diet may have a place in medical school and residency program curriculum as part of the standard of care for managing obesity-related chronic disease, but the literature is lacking in this area.

With this study, we aimed to assess medical students’ and family medicine residents’ perceptions of their current degree of nutrition training. We also aimed to specifically assess the awareness and perceptions of these trainees regarding a WFPB diet with regard to current curriculum and patient counseling. Last, we aimed to gather qualitative ideas from current trainees regarding how and where a reform of nutrition curriculum is desired. With this study, we hope to contribute to the limited body of evidence on the need for effective, evidence-based nutrition curriculum in US medical schools and residency programs, which has been identified as an area in need of further research.

Materials and Methods

Instruments

We created an original survey instrument (see Supplemental Appendix A) to collect baseline data on perceptions of current nutrition curricula, awareness of WFPB diet benefits, and willingness to prescribe such a diet to current and future patients. The survey consisted of 5 sections: Demographics, Diet, Recommendation, Barriers, and Curriculum. The Demographics section contained multiple choice questions for training year, areas of interest, and biological sex. The Diet section provided a definition for WFPB diet and included 5-point Likert-type scale responses to current diet perceptions and an open-ended question about WFPB diet perceptions. It also included 4 yes/no questions that grouped students and residents into the following groups: (1) awareness of the WFPB diet, (2) familiar with the health benefits of a WFPB diet, (3) current followers of a WFPB diet or variation (including vegan, vegetarian, or semivegetarian), and (4) past followers of a WFPB diet or variation.

The Recommendation and Barriers sections included Likert-type scale responses to various reasons the respondent would or would not recommend a WFPB diet to patients for 3 weeks and free text options for additional comments. The Curriculum section included Likert-type scale responses to proposed WFPB-nutrition-focused additions to medical curriculum, perceptions of existing nutrition curriculum, and three free text options for additional comments about more information, nutrition education in medical school, and related thoughts.

Procedures

Our research study was conducted at the University of Louisville School of Medicine, a mid-sized Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)–accredited medical school with an affiliated Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited family medicine residency program located in Louisville, Kentucky. After being granted exemption by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board, an online version of the original survey was emailed to first- through fourth-year medical students via a URL link with 3 reminder emails every 2 weeks. A preamble was included as an attachment to each email to explain the purpose of the study and notify that the participant’s completion of the survey served as written informed consent. Qualtrics, an electronic survey tool, was selected in order to protect the security and anonymity of the individual students’ responses. An identical survey and preamble were given as hard paper copies to resident physicians-in-training in the University of Louisville Department of Family Medicine during a weekly meeting and securely collected by a member of the research team using an unlabeled envelope. Inclusion criteria were first through fourth-year medical students and first- through third-year family medicine residents at the University of Louisville School of Medicine. Other parties at the University of Louisville School of Medicine, such as staff, faculty, and physicians were excluded from the study.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data from the student and resident surveys were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics for the 4 yes/no response questions dealing with students’ awareness of the WFPB diet were tabulated. Questions addressing respondents’ perception of nutrition and WFPB diet education in medical school were also tabulated. The Mann-Whitney U statistic was used to address differences within the 4 awareness groups regarding the 9 proposed reasons for recommending the WFPB diet. Each of the 9 proposed reasons provided a 5-point Likert-type scale response format ranging from “definitely would not recommend” to “already recommending.” Furthermore, Pearson’s chi-square was used to compare the respondents’ familiarity group to their likelihood of recommending a WFPB diet to patients in general based on a condensed version of the 5-point Likert-type scale response format (moderately and extremely likely versus moderately and extremely unlikely versus neither likely nor unlikely). Descriptive statistics of what respondents felt were barriers that might hinder patients from incorporating a WFPB diet were calculated, along with 95% confidence intervals for the percentages in agreement with these items. Likewise, descriptive statistics were calculated for items in the curriculum section that addressed what might change the respondent’s mind and cause them to recommend a WFPB diet. Group allocation to each of the familiarity groups is discussed in the Quantitative Data section. All P values were 2-tailed, and significance was set by convention at P < .05.

The qualitative data were analyzed using Dedoose. All free text responses in the Diet, Recommendations, and Barriers sections were coded as positive, negative, or neutral. Both positive and negative categories were then subcoded into “Alternatives,” “Environmental,” “Evidence,” “Feasibility,” “Financial,” “General,” “Health,” and “Personal Preference.” Groups with 20 or more responses were subcategorized further. Free text responses in the Curriculum section were coded as “None,” “Format,” “Improvement in Current Courses,” “Changes Not Necessary,” “Perspective,” and “Time Constraint.” Free text responses to the Additional Information/General Comments question at the end of the survey were coded as “Alternatives,” “Education,” “Evidence,” “None,” “Personal Experience,” “Resources,” “Social Determinants Impact,” “Specific Food Groups,” and “General Comments.” The breakdown of subcoded responses is included in the Qualitative Data section. Frequency of responses within each code, co-occurrences of codes, and individual quotes were used to supplement quantitative data.

Results

Quantitative Data

Of 644 medical students, 182 (28%) responded to the survey. Of 24 family medicine residents, 18 (75%) responded to the survey. The combined response rate was 30%, including the 31 (15.5%) that did not fully complete the survey. Of the 200 respondents, 49.5% were male, 50% were female, and 0.5% did not report. Responses were obtained from trainees in each training class: medical students in their first year (n = 52), second year (n = 85), third year (n = 28), and fourth year (n = 17) and residents in their first (n = 5), second (n = 7), and third years (n = 6). The allocation of respondents to the four familiarity groups is shown in Table 1. The 4 groups were not mutually exclusive and respondents were able to select “yes” for more than one group.

Table 1.

Allocation of Respondents to the 4 Familiarity Groups.

| I am familiar with or have heard of a WFPB diet (awareness group) | I am familiar with the health benefits of a WFPB diet (health benefits group) | I have tried a WFPB diet or variation (vegan, vegetarian, semivegetarian) in the past (past followers group) | I currently follow a WFPB diet or variation (vegan, vegetarian, semivegetarian) (current followers group) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | |

| Yes | 185 | 93 | 165 | 83 | 52 | 26 | 27 | 14 |

| No | 15 | 8 | 35 | 17 | 148 | 74 | 173 | 87 |

Abbreviation: WFPB diet, whole-foods, plant-based diet.

In the Recommendations section, we found that the current followers group was significantly more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients than those who were not current followers for each of the 9 proposed reasons, shown in Table 2. The current followers group was also significantly more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients in general than those who were not current followers (59% vs 17%, P < .001). The past followers group was significantly more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients than those who were not past followers for 8 of the 9 proposed reasons, demonstrated in Table 3. The past followers group was also significantly more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients in general than those who were not past followers (80% vs 46%, P < .001). The health benefits group was significantly more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients than those not in the health benefits group for all 9 proposed reasons, indicated in Table 4. The health benefits group was also significantly more likely to recommend a WFPB diet in general than those who were not (59% vs 17%, P < .001). There were no statistically significant differences between those in the awareness group and those not in the group for any of the 9 reasons or for the likelihood to recommend a WFPB diet in general (P = .178).

Table 2.

“How likely would you be to recommend a WFPB diet to your patients for 3 weeks for each of the statements given” by Current Follower (n = 27) or Not a Current Follower (n = 162).

| Definitely will NOT recommend for this reason (1) | Might recommend to CERTAIN patients for this reason (2) | Would probably recommend to MOST patients for this reason (3) | Definitely WOULD recommend for this reason (4) | I am ALREADY recommending or planning to recommend to patients for this reason (5) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Currently follow: | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Mean | SD | P | |

| To lower saturated fat intake | Yes | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 17 | 63 | 5 | 19 | 3.89 | 0.85 | .001 |

| No | 6 | 4 | 45 | 28 | 37 | 23 | 64 | 40 | 10 | 6 | 3.17 | 1.02 | ||

| To lower cholesterol to normal levels | Yes | 0 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 7 | 17 | 63 | 4 | 15 | 3.78 | 0.89 | .004 |

| No | 4 | 2 | 45 | 28 | 43 | 27 | 57 | 35 | 13 | 8 | 3.19 | 1.01 | <.001 | |

| To manage or cure heart disease | Yes | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 4 | 15 | 16 | 59 | 4 | 15 | 3.78 | 0.85 | |

| No | 8 | 5 | 50 | 31 | 39 | 24 | 54 | 33 | 11 | 7 | 3.06 | 1.06 | ||

| To lower blood pressure to normal levels | Yes | 0 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 17 | 63 | 5 | 19 | 3.85 | 0.91 | <.001 |

| No | 6 | 4 | 56 | 35 | 39 | 24 | 49 | 30 | 11 | 7 | 3.02 | 1.04 | ||

| To manage or cure diabetes | Yes | 0 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 3 | 11 | 15 | 56 | 4 | 15 | 3.67 | 0.96 | .002 |

| No | 13 | 8 | 51 | 31 | 39 | 24 | 46 | 28 | 13 | 8 | 2.97 | 1.12 | ||

| To lose weight | Yes | 0 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 1 | 4 | 17 | 63 | 4 | 15 | 3.74 | 0.94 | <.001 |

| No | 4 | 2 | 64 | 40 | 39 | 24 | 47 | 29 | 8 | 5 | 2.94 | 0.99 | ||

| To prevent chronic diseases | Yes | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 22 | 13 | 48 | 5 | 19 | 3.74 | 0.90 | <.001 |

| No | 18 | 11 | 58 | 36 | 36 | 22 | 42 | 26 | 8 | 5 | 2.78 | 1.10 | ||

| To go off of prescription medication | Yes | 0 | 0 | 8 | 30 | 4 | 15 | 12 | 44 | 3 | 11 | 3.37 | 1.04 | <.001 |

| No | 25 | 15 | 71 | 44 | 30 | 19 | 28 | 17 | 8 | 5 | 2.52 | 1.10 | ||

| To slow down/prevent cancer | Yes | 2 | 7 | 5 | 19 | 7 | 26 | 10 | 37 | 3 | 11 | 3.26 | 1.13 | .001 |

| No | 32 | 20 | 65 | 40 | 26 | 16 | 33 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 2.48 | 1.13 | ||

Abbreviation: WFPB diet, whole-foods, plant-based diet.

Table 3.

“How likely would you be to recommend a WFPB diet to your patients for 3 weeks for each of the statements given” by Past Follower (n = 51) or Not Past Follower (n = 138).

| Definitely will NOT recommend for this reason (1) | Might recommend to CERTAIN patients for this reason (2) | Would probably recommend to MOST patients for this reason (3) | Definitely WOULD recommend for this reason (4) | I am ALREADY recommending or planning to recommend to patients for this reason (5) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past follower: | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Mean | SD | P | |

| To lower saturated fat intake | Yes | 2 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 55 | 8 | 16 | 3.67 | 1.01 | .001 |

| No | 4 | 3 | 42 | 30 | 32 | 23 | 53 | 38 | 7 | 5 | 3.12 | 1.00 | ||

| To lower cholesterol to normal levels | Yes | 1 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 18 | 26 | 51 | 8 | 16 | 3.65 | 0.98 | .001 |

| No | 3 | 2 | 42 | 30 | 36 | 26 | 48 | 35 | 9 | 7 | 3.13 | 1.00 | ||

| To manage or cure heart disease | Yes | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 9 | 18 | 26 | 51 | 6 | 12 | 3.51 | 1.03 | .004 |

| No | 6 | 4 | 45 | 33 | 34 | 25 | 44 | 32 | 9 | 7 | 3.04 | 1.04 | ||

| To lower blood pressure to normal levels | Yes | 1 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 6 | 12 | 25 | 49 | 9 | 18 | 3.61 | 1.06 | <.001 |

| No | 5 | 4 | 50 | 36 | 34 | 25 | 41 | 30 | 7 | 5 | 2.96 | 1.01 | ||

| To manage or cure diabetes | Yes | 3 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 11 | 22 | 22 | 43 | 7 | 14 | 3.43 | 1.10 | .005 |

| No | 10 | 7 | 48 | 35 | 31 | 22 | 39 | 28 | 10 | 7 | 2.93 | 1.10 | ||

| To lose weight | Yes | 0 | 0 | 14 | 27 | 6 | 12 | 25 | 49 | 6 | 12 | 3.45 | 1.03 | .002 |

| No | 4 | 3 | 55 | 40 | 34 | 25 | 39 | 28 | 6 | 4 | 2.91 | 0.99 | ||

| To prevent chronic diseases | Yes | 2 | 4 | 11 | 22 | 12 | 24 | 21 | 41 | 5 | 10 | 3.31 | 1.05 | .003 |

| No | 16 | 12 | 50 | 36 | 30 | 22 | 34 | 25 | 8 | 6 | 2.77 | 1.12 | ||

| To go off of prescription medication | Yes | 2 | 4 | 21 | 41 | 9 | 18 | 16 | 31 | 3 | 6 | 2.94 | 1.07 | .022 |

| No | 23 | 17 | 58 | 42 | 25 | 18 | 24 | 17 | 8 | 6 | 2.54 | 1.13 | ||

| To slow down/ prevent cancer |

Yes | 6 | 12 | 17 | 33 | 9 | 18 | 16 | 31 | 3 | 6 | 2.86 | 1.17 | .050 |

| No | 28 | 20 | 53 | 38 | 24 | 17 | 27 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 2.49 | 1.15 | ||

Abbreviation: WFPB diet, whole-foods, plant-based diet.

Table 4.

“How likely would you be to recommend a WFPB diet to your patients for 3 weeks for each of the statements given” by Health Benefits Group (n = 155) or Not Health Benefits Group (n = 34).

| Definitely will NOT recommend for this reason (1) | Might recommend to CERTAIN patients for this reason (2) | Would probably recommend to MOST patients for this reason (3) | Definitely WOULD recommend for this reason (4) | I am ALREADY recommending or planning to recommend to patients for this reason (5) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aware of health benefits | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Mean | SD | P | |

| To lower saturated fat intake | Yes | 4 | 3 | 30 | 19 | 32 | 21 | 74 | 48 | 15 | 10 | 3.43 | 0.99 | <.001 |

| No | 2 | 6 | 18 | 53 | 7 | 21 | 7 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 2.56 | 0.89 | ||

| To lower cholesterol to normal levels | Yes | 2 | 1 | 32 | 21 | 36 | 23 | 68 | 44 | 17 | 11 | 3.43 | 0.98 | <.001 |

| No | 2 | 6 | 17 | 50 | 9 | 26 | 6 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2.56 | 0.86 | ||

| To manage or cure heart disease | Yes | 5 | 3 | 34 | 22 | 37 | 24 | 65 | 42 | 14 | 9 | 3.32 | 1.02 | <.001 |

| No | 3 | 9 | 19 | 56 | 6 | 18 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 2.47 | 0.96 | ||

| To lower blood pressure to normal levels | Yes | 3 | 2 | 41 | 27 | 35 | 23 | 59 | 38 | 16 | 10 | 3.29 | 1.03 | <.001 |

| No | 3 | 9 | 19 | 56 | 5 | 15 | 7 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 2.47 | 0.93 | ||

| To manage or cure diabetes | Yes | 7 | 5 | 39 | 25 | 38 | 25 | 56 | 36 | 15 | 10 | 3.21 | 1.07 | <.001 |

| No | 6 | 18 | 17 | 50 | 4 | 12 | 5 | 15 | 2 | 6 | 2.41 | 1.13 | ||

| To lose weight | Yes | 3 | 2 | 47 | 30 | 35 | 23 | 58 | 37 | 12 | 8 | 3.19 | 1.02 | <.001 |

| No | 1 | 3 | 22 | 65 | 5 | 15 | 6 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2.47 | 0.83 | ||

| To prevent chronic diseases | Yes | 11 | 7 | 46 | 30 | 36 | 23 | 50 | 32 | 12 | 8 | 3.04 | 1.10 | .001 |

| No | 7 | 21 | 15 | 44 | 6 | 18 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 2.35 | 1.07 | ||

| To go off of prescription medication | Yes | 16 | 10 | 61 | 39 | 31 | 20 | 37 | 24 | 10 | 6 | 2.77 | 1.12 | .001 |

| No | 9 | 26 | 18 | 53 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 2.09 | 1.00 | ||

| To slow down/prevent cancer | Yes | 20 | 13 | 56 | 36 | 30 | 19 | 40 | 26 | 9 | 6 | 2.75 | 1.15 | <.001 |

| No | 14 | 41 | 14 | 41 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1.85 | 0.93 | ||

Abbreviation: WFPB diet, whole-foods, plant-based diet.

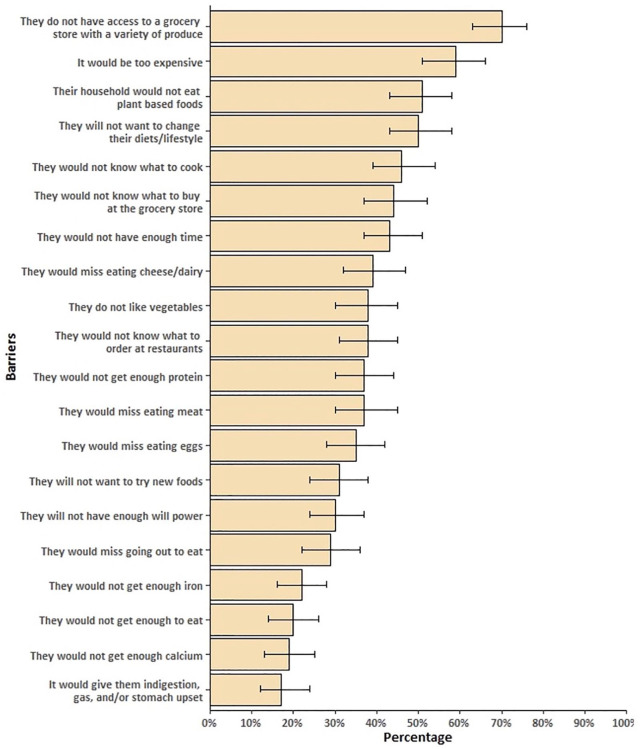

The 20 proposed barriers to recommending a WFPB diet to patients are demonstrated in Figure 1 via the percentage of respondents who were in agreement with each barrier statement. Of the 20 proposed barriers, the greatest number of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that patients “do not have access to a grocery store with a variety of produce” (3.79 ± 1.08). Respondents also generally agreed or strongly agreed that “it would be too expensive” (3.54 ± 1.16), “[patients’] household would not want to eat plant-based foods” (3.30 ± 1.11), and “[patients] will not want to change their diets/lifestyle” (3.34 ± 1.17). Fewer than half of respondents agreed with the remaining barrier statements. Notably, 66% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement, “[patients] would not get enough to eat” (2.39 ± 1.17). While 56% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “they would not get enough iron” (2.57 ± 1.01). Almost half (47%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement “they would not get enough protein” (2.91 ± 1.16).

Figure 1.

Percentage of students and residents who agreed or strongly agreed with questions addressing patient’s barriers to incorporating a whole-foods, plant-based (WFPB) diet into their lifestyle. Error bars reflect 95% confidence intervals.

In the Curriculum section, only 22% of respondents agreed with the statement “I received or am receiving enough nutrition education in my medical school training,” while 78% disagreed or were neutral. There was no significant difference between training class (P = .561). Regarding the statement “More focus should be put on WFPB nutrition in medical school and/or residency programs,” 41% agreed while 59% disagreed or were neutral. There was no significant difference between training class. Analysis of the proposed WFPB nutrition–focused additions to medical curriculum in the Curriculum section showed that 79% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that “Seeing that a WFPB diet works for others in clinical practice” would make them more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients (3.88 ± 0.88). Sixty-nine percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that “Getting more information or evidence in general” would make them more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients (3.81 ± 0.97). Similarly, 69% of respondents also agreed or strongly agreed that “Seeing a nutritionally complete and detailed WFPB meal plan” would make them more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients (3.75 ± 0.98). The fewest number of respondents agreed that “adding WFPB nutrition competencies to internal medicine and/or family medicine residency requirements” (50%; 3.23 ± 1.11) and “adding WFPB nutrition competencies to cardiology licensure requirements” (43%; 3.15 ± 1.05) would make them more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients. Data are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

What Factors Might Help Change Your Mind to Recommend a WFPB Diet (n = 173).

| Strongly disagree/disagree (1-2) | Neutral (3) | Agree/strongly agree (4-5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Mean | SD | |

| Seeing that a whole-foods, plant-based diet works for others in clinical practice | 15 | 9 | 22 | 13 | 136 | 79 | 3.88 | 0.88 |

| Getting more information or evidence in general | 16 | 9 | 37 | 21 | 120 | 69 | 3.81 | 0.97 |

| Seeing a nutritionally complete and detailed whole-foods, plant-based meal plan | 21 | 12 | 32 | 18 | 120 | 69 | 3.75 | 0.98 |

| Attending a whole-foods, plant-based cooking class as an elective in medical school | 37 | 21 | 34 | 20 | 102 | 59 | 3.41 | 1.05 |

| Doing my own research on whole-foods, plant-based nutrition | 39 | 23 | 34 | 20 | 100 | 58 | 3.39 | 1.07 |

| Incorporating more whole-foods, plant-based nutrition into current medical school classes | 35 | 20 | 43 | 25 | 95 | 55 | 3.34 | 0.98 |

| Attending a whole-foods, plant-based nutrition elective in medical school | 42 | 24 | 43 | 25 | 88 | 51 | 3.29 | 0.99 |

| If more focus were put on whole-foods, plant-based nutrition on national boards or shelf examinations | 50 | 29 | 39 | 23 | 82 | 48 | 3.23 | 1.14 |

| Adding whole-foods, plant-based nutrition competencies to internal medicine and/or family medicine residency requirements | 48 | (28%) | 39 | (23%) | 86 | (50%) | 3.23 | (1.11) |

| Adding whole-foods, plant-based nutrition competencies to cardiology licensure requirements | 48 | 28 | 50 | 29 | 75 | 43 | 3.15 | 1.05 |

Abbreviation: WFPB diet, whole-foods, plant-based diet.

Qualitative Data

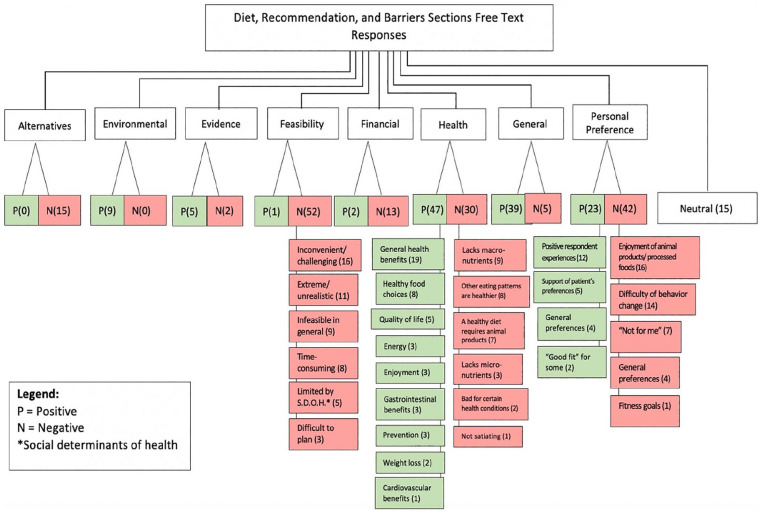

The most common positive theme for recommending a WFPB diet to patients was “Health Benefits” with 47 free text responses. The second most common theme was “General Positive” with 39 free text responses, which could not be subdivided into smaller themes due to the nonspecific nature of the responses. The next most common themes in descending order were “Personal Preference,” “Environment,” “Evidence,” “Financial,” and “Feasibility.” The negative themes for recommending a WFPB diet to patients from most common to least common were “Feasibility,” “Personal Preference,” “Health,” “Alternatives,” “Financial,” “General Negative,” and “Evidence.” The breakdown of subcoded responses for both positive and negative themes is shown in Figure 2. Notably, multiple responses included both positive and negative themes: 17 responses involved an overlap of “General Positive” and “Negative Feasibility” while 11 other responses involved an overlap of “General Health Benefits” and “Negative Personal Preference.” There were 15 Neutral free text responses.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of coded and subcoded qualitative free text responses in the Diet, Recommendation, and Barriers sections.

In the Curriculum section, the most common free text response regarding nutrition in medical school curriculum involved instruction on a WFPB diet as a component of a broad approach covering a variety of dietary patterns rather than the exclusive focus (12 responses). Additional responses involved focusing on how to counsel patients (9 responses), improving current nutrition education (6 responses) or creating a dedicated nutrition course (6 responses), focusing a course on evidence-based nutrition (5 responses), and targeting the goals of students rather than patients (3 responses). Of note, 3 respondents answered that changes to current curriculum were not necessary, and 5 respondents cited that there was not enough time in the educational schedule for dedicated nutrition training in medical school. Regarding additional information in general, 26 respondents desired additional evidence-based nutrition in the form of peer-reviewed research studies focused on WFPB dietary patterns. Other common categories of desired additional information included education (7 responses), impact on social determinants of health (5 responses), resources (6 responses) for both physicians (1 responses) and patients (3 responses), and personal experience (2 responses).

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussion of Findings

Medical literature in the United States has been drawing attention to the lack of adequate nutrition training in medical school since at least 1990 35 and as recent as 2019. 36 Despite these calls to action, the presence of nutrition in medial curriculum has remained largely static across the country and trainees continue to report unsatisfactory nutrition training.1-14 Doctors, therefore, consistently feel inadequately prepared to counsel their patients on evidence-based nutritional guidelines2-4,9,12,15,30-33 despite a belief in the importance of nutrition counseling in patient care.32-34 Our findings were consistent with current national literature in that most respondents perceived insufficient training in nutrition during medical school. The fact that there was no significant difference between training class suggests that there is little to no increase in exposure to clinical nutrition as one matriculates through undergraduate and graduate medical training. Through the free text responses, both students and residents expressed a desire for curricular reform pertaining to nutrition, most frequently citing the importance of dietary counseling for chronic disease management. Many also disclosed uncertainty about their ability to provide nutritional counseling: “I do not have confidence right now recommending any diets or nutrition plans to patients with chronic diseases (i.e. hypertension or renal disease),” wrote one respondent. Another student addressed the impracticality of current nutrition curriculum, responding, “[w]e need more instruction on what works for patients and how to help real people, not just the ideal 70-kg man or a hypothetical patient in a question stem.” Trainees seem to understand the complexity of implementing nutritional guidelines in patient care; however, they also perceive the gap between what they are taught in medical school and the actual clinical application of these topics.

When considering reform of current medical training in nutrition, the question remains as to which areas of nutrition to address and where to fit them. Medical students are expected to learn an enormous amount of information in a short amount of time. For this reason, many trainees cited concern that there may not be time or space for a substantial focus on nutrition. One respondent said, “nutrition isn’t given enough time in med school I agree, but there’s just so much to learn,” while another reported “[h]onestly, we probably need more nutrition but there isn’t really space . . .” Therefore, any proposed reform to nutrition curriculum necessitates a concise, deliberate approach while still addressing the most current literature. Such an approach could include principles of a WFPB dietary pattern given its growing body of supporting evidence. Although statistically insignificant, over half of our respondents were amenable to the addition of WFPB dietary principles to medical training. Many respondents included a stipulation that it should be taught alongside other healthy dietary patterns rather than as an exclusive way of eating.

Despite a general understanding that a WFPB diet offers various health benefits, multiple qualms about its implementation were cited by our respondents. Thirty-two free text responses were obtained that included both an affirmation and a caveat to either adopting or recommending a WFPB diet. The 17 responses that included a co-occurrence of “General Positive” and “Negative Feasibility” primary acknowledged that a WFPB diet is, in general, a “good idea” however it would be too difficult or unrealistic to implement. For example, one respondent stated, “It’s a good but difficult option for some if not most patients” while another stated, “I really like the idea but it can be difficult to plan and go shopping for everything.” An additional 17 responses similarly addressed the health benefits of a WFPB diet specifically but contradicted them with personal preferences. Ten of these responses specifically cited enjoyment of meat, dairy, and other animal products, for example, “Great option, I wish I could get myself to do it, but I love meat and dairy too much to quit them.” Of note, none of the responses with co-occurring positive and negative themes endorsed ever having tried to adopt or recommend a WFPB diet. These findings suggest that personal preference and perceived barriers may have a stronger effect than the scientific evidence supporting a given behavioral modification. A greater emphasis on behavior change and motivational interviewing alongside the evidence-based principles behind nutritional guidelines may therefore be a worthwhile focus when considering reform of current medical curriculum.

Interestingly, our findings also suggest that personal experience with a WFPB diet positively influences a respondent’s likelihood of implementing it in future patient care. Being in the health benefits group, current followers group, or past followers group made a respondent significantly more likely to be willing to recommend a WFPB diet to future patients while being in the awareness group did not. These findings suggest that a positive personal experience with such a diet change may be a stronger indicator of an inclination to counsel future patients on WFPB nutrition than just being aware of a WFPB diet. This also suggests that, although many respondents cited a desire for more evidence-based medicine to support a WFPB diet, a positive personal experience may be more impactful. This is consistent with the 79% of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed that “Seeing that a WFPB diet works for others in clinical practice” would make them more likely to recommend a WFPB diet to patients. Anecdotal experiences, although scientifically weak, seem to be a strong factor driving future patient care among our respondents. Based on these preliminary findings, it can be inferred that teaching medical trainees an evidence-based approach to WFPB nutrition with a focus on personal implementation might make them more likely to adopt a WFPB diet, either partially or fully. This could, in turn, increase their willingness to counsel future patients on the benefits of adopting a WFPB diet.

Efforts have recently been made in the medical community to draw attention to the plant-predominant dietary movement. The Lancet has identified a plant-based diet centered around fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and unsaturated oils as a “reference diet” for optimal human health and environmental sustainability. 28 The American Heart Association also released an advisory calling for improved medical training that focuses on a plant-based diet. 16 However, it seems as if the scientific support behind a plant-based diet is not being adequately communicated to medical trainees and physicians. Although 85% of respondents reported that they are familiar with the health benefits of a WFPB diet, 69% still desired more information or evidence in general before recommending it to patients. Likewise, 26 free text responses claimed that evidence supporting a WFPB diet is lacking, which is inconsistent with the fact that there is a significant amount of data that robustly backs plant-predominant and plant-exclusive diets, including the WFPB diet, for the prevention and management of chronic diseases. A discrepancy exists between what many respondents perceive to be true and the actual state of current evidence-based nutrition, which draws further attention to the need for its inclusion in medical training. A recent article pointed out that healthcare professionals are no more knowledgeable than the general public about a WFPB diet, 29 which greatly limits its potential as an effective lifestyle modification technique. Educating physicians early in their career about the health benefits of plant-based diets, including the WFPB diet, could ultimately contribute to both healthier doctors and healthier patients.

Our preliminary study has begun to highlight medical trainees’ views of WFPB nutrition in medical training and patient care. This has come following multiple calls to action by various governing bodies in the medical community as a response to the growing diet-related chronic disease burden in our country. A movement toward a more plant-forward way of eating has the potential to address this chronic disease burden, but its implementation must start with the physician workforce. A focus on nutrition competencies in medical training are therefore more important than ever. Equally important is the acceptability of dietary modification in our patient populations, which will be a focus of our future research.

Limitations

Our study was limited by small sample size and a low (30%) overall response rate. Given the fact that participation in this survey was optional, it is possible that those respondents with stronger opinions regarding medical school nutrition curriculum were the voices that predominated. Those respondents with stronger opinions were also more likely to have completed the survey in its entirety, including the optional free-text response boxes, potentially skewing results. It is also important to consider that our sample was drawn from a single medical school and residency program within the same institution, and thus makes our results more difficult to generalize to a wider population of students and residents in both the United States and internationally. As with any survey-based study, our results could have been affected by reporting bias among respondents.

The nature of our study also creates a bias in favor of a WFPB diet. Other similar dietary patterns, such as vegan, vegetarian, Mediterranean, etc. were intentionally excluded from our study to directly target perceptions of a WFPB diet specifically. However, this may convey the idea that a WFPB diet is perceived by respondents as superior to other similar diets, which cannot be concluded from our findings. Further study is required to compare the acceptability of these similar dietary patterns as an addition to medical school curriculum and dietary counseling for patients.

Conclusions

Our study was meant to evaluate medical students’ and family medicine residents’ perceptions of their nutrition training in medical school. Despite our low overall response rate, our findings clearly agreed with current literature in that most trainees perceive inadequate nutrition training during medical school. Our findings also supported that there may indeed be a place for WFPB nutrition-focused curriculum in medical training given the positive interest in WFPB nutrition reported by respondents in this study. However, a WFPB dietary focus may be more accepted by medical trainees if presented alongside other healthy dietary patterns. Our study revealed multiple areas of interest with regards to additions to nutrition curriculum in medical school, including optional electives during medical school and residency, lunchtime presentations, and evidence-based medicine, which could each be realistically implemented throughout medical training.

Our research is the first to explore the acceptability of WFPB diet-focused curriculum as an addition to nutrition education in medical school, therefore further study is warranted. Areas of additional research opened by our study might include the implementation and acceptability of a WFPB diet-focused curriculum in medical school and perceptions of a WFPB diet in patient populations. Administration of this survey tool to medical students and residents over multiple years could also provide a more concrete assessment of trainee’s perceptions of their nutrition curriculum as well as potential changes in perceptions as curricular interventions are employed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ajl-10.1177_1559827620988677 for A Place for Plant-Based Nutrition in US Medical School Curriculum: A Survey-Based Study by Kara F. Morton, Diana C. Pantalos, Craig Ziegler and Pradip D. Patel in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Eli Pendleton, MD for his assistance with resident data collection, and Susan Sawning, MSSW and Emily Noonan, PhD for guidance in the qualitative analysis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable.

Informed Consent: Not applicable.

Trial Registration: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: Kara F. Morton  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5409-6648

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5409-6648

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Kara F. Morton, Department of Undergraduate Medical Education, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky.

Diana C. Pantalos, Department of Pediatrics, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

Craig Ziegler, University of Louisville Office of Undergraduate Medical Education, Louisville, Kentucky.

Pradip D. Patel, Department of Pediatrics, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

References

- 1.Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition education in US medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med. 2010;85:1537-1542. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab71b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danek RL, Berlin KL, Waite GN, Geib RW. Perceptions of nutrition education in the current medical school curriculum. Fam Med. 2017;49:803-806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devries S, Dalen JE, Eisenberg DM, et al. A deficiency of nutrition education in medical training. Am J Med. 2014;127:804-806. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frantz DJ, McClave SA, Hurt RT, Miller K, Martindale RG. Cross-sectional study of US interns’ perceptions of clinical nutrition education. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40:529-535. doi: 10.1177/0148607115571016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramlich LM, Olstad DL, Nasser R, et al. Medical students’ perceptions of nutrition education in Canadian universities. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35:336-343. doi: 10.1139/H10-016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hargrove EJ, Berryman DE, Yoder JM, Beverly EA. Assessment of nutrition knowledge and attitudes in preclinical osteopathic medical students. J Amer Osteopath Assoc. 2017;117:622-633. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2017.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiraly LN, McClave SA, Neel D, Evans DC, Martindale RG, Hurt RT. Physician nutrition education. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:332-337. doi: 10.1177/0884533614525212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Bales CW, et al. The need to advance nutrition education in the training of health care professionals and recommended research to evaluate implementation and effectiveness. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5 suppl):1153S-1166S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair D, Hart A. Family physicians’ perspectives on their weight loss nutrition counseling in a high obesity prevalence area. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:522-528. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.04.170467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips E, Pojednic R, Polak R, Bush J, Trilk J. Including lifestyle medicine in undergraduate medical curricula. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:26150. 10.3402/meo.v20.26150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pojednic R, Frates E. A parallel curriculum in lifestyle medicine. Clin Teach. 2017;14:27-31. doi: 10.1111/tct.12475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreiber KR, Cunningham FO. Nutrition education in the medical school curriculum: a review of the course content at the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland-Bahrain. Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185:853-856. doi: 10.1007/s11845-015-1380-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torabi MR, Tao R, Jay SJ, Olcott C. A cross-sectional survey on the inclusion of tobacco prevention/cessation, nutrition/diet, and exercise physiology/fitness education in medical school curricula. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:400-406. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30336-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crowley J, Ball L, Hiddink GJ. Nutrition in medical education: a systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3:e379-e389. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devries S, Freeman AM. Nutrition education for cardiologists: the time has come. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19:77. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0890-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aspry KE, Van Horn L, Carson JAS, et al. Medical nutrition education, training, and competencies to advance guideline-based diet counseling by physicians: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e821-e841. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushner RF, Van Horn L, Rock CL, et al. Nutrition education in medical school: a time of opportunity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5 suppl):1167S-1173S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Horn L, Lenders CM, Pratt CA, et al. Advancing nutrition education, training, and research for medical students, residents, fellows, attending physicians, and other clinicians: building competencies and interdisciplinary coordination. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:1181-1200. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh HK, Parekh AK. Toward a United States of health: implications of understanding the US burden of disease. JAMA. 2018;319:1438-1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meldrum DR, Morris MA, Gambone JC. Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertil Steril. 2017;107:833-839. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hever J, Cronise RJ. Plant-based nutrition for healthcare professionals: implementing diet as a primary modality in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14:355-368. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gould KL, Ornish D, Scherwitz L, et al. Changes in myocardial perfusion abnormalities by positron emission tomography after long-term, intense risk factor modification. JAMA. 1995;274:894-901. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530110056036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson JW, Ward K. High-carbohydrate, high-fiber diets for insulin-treated men with diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 1979;32:2312-2321. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/32.11.2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJA, et al. A low-fat vegan diet and a conventional diabetes diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled, 74-wk clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1588S-1596S. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnard ND, Katcher HI, Jenkins DJA, Cohen J, Turner-McGrievy G. Vegetarian and vegan diets in type 2 diabetes management. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:255-263. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benatar JR, Stewart RAH. Cardiometabolic risk factors in vegans; a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang T, Yang B, Zheng J, Li G, Wahlqvist ML, Li D. Cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer incidence in vegetarians: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;60:233-240. doi: 10.1159/000337301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willett W, Rockstrom J, Loken B, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393:447-492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mondala MM, Sannidhi D. Catalysts for change: accelerating the lifestyle medicine movement through professionals in training. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13:487-494. doi: 10.1177/1559827619844505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition in medicine: nutrition education for medical students and residents. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:471-480. doi: 10.1177/0884533610379606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford AL, Aspry KE. Teaching doctors-in-training about nutrition: where are we going in 2016? R I Med J (2013). 2016;99:23-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoendorfer N, Gannaway D, Jukic K, Ulep R, Schafer J. Future doctors’ perceptions about incorporating nutrition into standard care practice. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36:565-571. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2017.1333928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolasa KM, Rickett K. Barriers to providing nutrition counseling cited by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:502-509. doi: 10.1177/0884533610380057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wynn K, Trudeau JD, Taunton K, Gowans M, Scott I. Nutrition in primary care: current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e109-e116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boker JR, Weinsier RL, Brooks MC, Olson AK. Components of effective clinical-nutrition training: a national survey of graduate medical education (residency) programs. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:568-571. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.3.568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devries S, Willett W, Bonow RO. Nutrition education in medical school, residency training, and practice. JAMA. 2019;321:1351-1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ajl-10.1177_1559827620988677 for A Place for Plant-Based Nutrition in US Medical School Curriculum: A Survey-Based Study by Kara F. Morton, Diana C. Pantalos, Craig Ziegler and Pradip D. Patel in American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine