Abstract

For a long time, fungal pathogens have been a threat to the health and diet of humans. Consequently, antimycotic agents have been developed, which are called fungicides in agriculture and antifungals in medicine. Because fungi constantly develop resistance to established modes of action and because of the need for reducing the required use rates/doses, immense research efforts are still being undertaken to discover novel antimycotics. The research-based agrochemical industry has proven that these requirements can be fulfilled by a constant flow of novel fungicidal modes of action, the expansion of agronomical scope and applicability of existing fungicidal mode of action classes, and the design of resistance-breaking active ingredients in an established fungicidal mode of action class, if the molecular structure of the mutated fungal strain is known. Such strategies could be also useful for the discovery of novel antifungals.

Keywords: Fungicide, Antifungal, Antimycotic, Crop protection, Resistance breaker

History of Fungicides and Antifungals

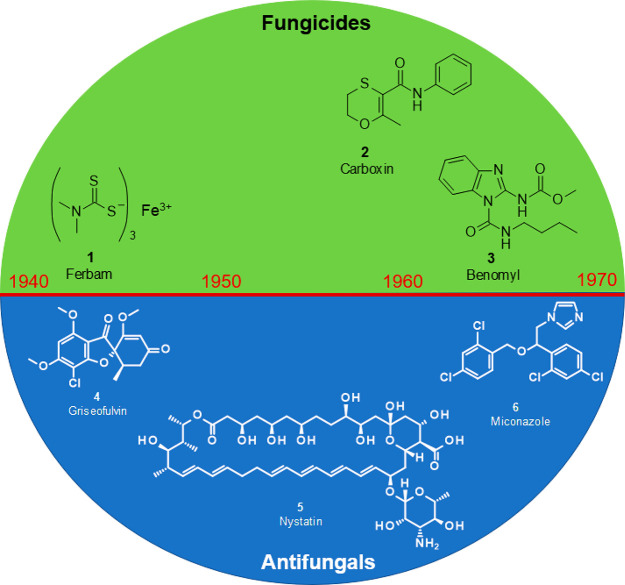

Since the earliest days of agriculture, fungal plant pathogens have endangered the food supply of mankind. However, in contrast to the easily visible competition of seedlings with undesired vegetation (weeds) and the devastation of harvests by insects, it took a long time—until the 19th century—before the causal agents of most plant diseases were identified as fungi. Although the reason for outbreaks of such plant diseases has remained mostly unclear, plant diseases have been treated with chemicals, called fungicides, for more than 3000 years. The history of agrochemical fungicides1−4 is closely linked to elemental sulfur, which is presumably the oldest of all crop protection chemicals.5 Its fungicidal properties were already known to the ancient Greeks, when nearly 30 centuries ago Homer referred to “pest-averting sulfur”. Most of the knowledge was lost until Forsyth rediscovered sulfur for the control of plant diseases in 1802.6 His recommendation for the control of powdery mildew on fruit trees was to spray a concoction of quicklime, sulfur, elderberry bud, and tobacco. Since 1824, powdered sulfur was widely applied against fruit and grape diseases, e.g., peach powdery mildew,7 until the second half of the 19th century, which saw the introduction of three further pioneering sulfur-containing fungicides: Eau Grison (calcium polysulfide, lime sulfur, CaS, Sx) in 1852,8 Bordeaux mixture [CuSO4 + Ca(OH)2, which react to generate Cu(OH)2 + CaSO4] in 1885 by Millardet,9 and Burgundy mixture (CuSO4 + Na2CO3) in 1887 by Masson.10 After further experimentation with copper salts, colloidal copper hydroxide was described as a foliar fungicide in 1923.11 Exactly 20 years later, the introduction of ferbam (1), an iron salt and one of the first dithiocarbamates, marked the birth of the first foliar broad-spectrum fungicide, which was widely used against rusts, molds, scabs, and other diseases.2 Further important milestones were achieved in the 1960s, with the introduction of the first fully systemic seed treatment agent (carboxin (2), a succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor, in 1966) and the launch of the first broad-spectrum foliar systemic fungicide (benomyl (3), a tubulin polymerization inhibitor, in 1968).3 Although the early beginnings of agrochemical disease control were linked to multi-site inhibitors which block non-specifically several different biochemical pathways, today’s typical fungicides are purely organic compounds which, in most cases, selectively block one single enzyme in a fungal biosynthesis pathway (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Important fungicide and antifungal milestones between 1940 and 1970.

The history of pharmaceutical antifungals12−15 began clearly much later. In the 1940s, pharmacological agents available for the treatment of fungal infections included potassium iodide, undecylenic acid, and phenolic dyes. Griseofulvin (4), a natural product derived from Penicillium griseofulvum which interferes with the intracellular tubulin polymerization, has been widely used against topical infections since the late 1940s, and then even as an orally effective antifungal since the early 1960s.16 Two of the major active ingredient classes on the antifungal market had their advent in the 1950s and 1960s. Nystatin (5), a macrolactone from Streptomyces noursei, has been applied since 1955 as the very first polyene derivative,17 and just 3 years later, with amphotericin B, an even more effective example of this class was found, which is still today one of the antimycotic gold standards.18 Miconazole (6), discovered at the end of the 1960s and commercialized quickly after, was the first azole reaching the pharmaceutical market, and because of its systemic action, it is also highly useful against deep mycoses (Figure 1).19

Fungicide and Antifungal Market Overview

Ensuring food security for a steadily growing human population remains one of the biggest challenges of our time. Currently, 7.8 billion people are living on Earth, a population which is forecasted to reach 9 billion before 2050 and the 10 billion mark at the end of this century.20 At the same time, the size of available arable land is shrinking, leading to the fact that the number of people fed per hectare of planted land is constantly rising: it has doubled from 3 in 1974 to almost 6 these days.21,22 This situation is further aggravated by the fact that, although the application of agrochemicals triples the native yield of the major crop plants rice and cotton and doubles the yield of corn, soybean, and potato, even with modern crop protection methods, each of these crops reaches only 60–75% of their theoretical maximum yield.22,23 Reasons for this unmet harvest potential are, among other things, fungal pathogens which cannot be controlled with the available fungicide arsenal or which develop resistance against established products. There are 8000 crop-damaging fungal species known, which are spread over all major phyla of the kingdom of true fungi: the Ascomycota (e.g., Uncinula necator, the causal agent of grape powdery mildew) and the Basidiomycota (e.g., Phakopsora pachyrhizi, the causal agent of Asian soybean rust).24 Several devastating plant diseases are also caused by members of the oomycota from the kingdom Chromista, e.g., Phytophthora infestans, the causal agent of potato and tomato late blight. For all the reasons mentioned above, there is a huge demand for agrochemical fungicides. In 2019, fungicide sales amounted to 16.36 billion USD, which was ca. one-third of the overall agrochemical market (59.28 billion USD). More than half of the fungicide sales have been achieved with sterol biosynthesis inhibitors (14α-demethylase inhibitors, in crop protection called DMIs) and respiration inhibitors (inhibitors of respiratory chain complexes II (succinate hydrogenase inhibitors, SDHIs) and III (strobilurins)), and the most important crops for fungicide application have been fruits and vegetables, cereals, and soybeans (Figure 2).25

Figure 2.

Fungicide and antifungal market size in 2019.

Compared to agrochemical fungicides, the market size for pharmaceutical antifungals is smaller: in 2019, the global sales of pharmaceutical antimycotics reached 10.24 billion USD.26 This market has been clearly dominated by inhibitors of 14α-demethylase within the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (in medicine called azoles), which accounted for more than half of all sales, followed by the echinocandins and the polyenes as the second and third biggest-selling families of antifungals. These three active ingredient classes make up more than 95% of the antifungal market, which means that this market is much less fragmented than the fungicide market, which contains several further mode of action classes. The threat of mycoses to human health is not less dramatic than that for the health of those plants required for the human diet. It is estimated that invasive fungal infections cause the death of 1.5–2 million people annually, and therefore they have a higher mortality rate than that of, for instance, malaria or tuberculosis.27−30 More than 90% of those deaths are attributed to Candida spp., e.g., albicans, parapsilosis, krusei, and tropicalis, and Aspergillus spp., e.g., fumigatus, flavus, niger, and parasiticus, which all belong to the phylum Ascomycota.12 The basidiomycete Cryptococcus neoformans is another type of such pathogens causing life-threatening invasive fungal infections. Especially at risk are immunocompromised patients, as a result of aggressive therapies, e.g., anticancer chemotherapy, long-term corticosteroid treatment, and organ transplant, or an immunosuppressive infection, such as HIV/AIDS (Figure 2).27−30

The 14α-Demethylase Inhibitors—The Only Major Overlapping Mode of Action on the Fungicide and Antifungal Market

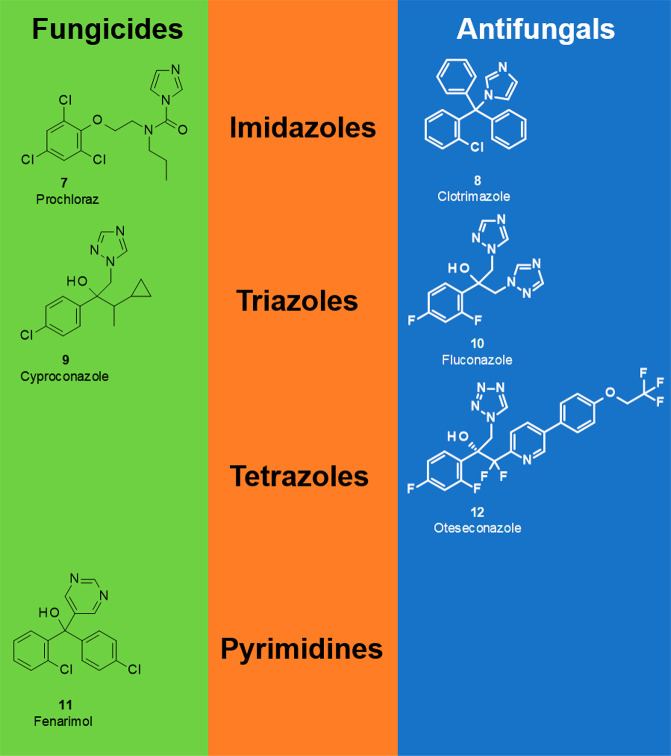

Inhibitors of 14α-demethylase constitute the biggest-selling mode of action class on both the fungicide and antifungal markets. Most of these active ingredients bear a common name which ends with “conazole”. 14α-Demethylase (CYP51) belongs to the family of cytochrome P450 enzymes and facilitates the transformation of 24-methylenedihydrolanosterol (eburicol) to 4,4-dimethylergosta-8,14,24(28)-trien-3β-ol, which is the fourth step in the complex biosynthesis cascade from the acyclic terpenoid squalene to the tetracyclic steroid ergosterol, the major cell membrane component of all fungi belonging to the phyla of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. In principle, inhibition of any of these steps leads to pronounced fungicidal effects, primarily through the depletion of ergosterol required for fungal tissue development, but potentially also by accumulation of sterols with unfavorable properties. An important structural requirement of the 14α-demethylase inhibitors, which are called DMIs31−33 in crop protection and azoles34−36 in medicine, is an sp2-configured ring nitrogen with two unsubstituted neighboring CH or N ring members in the adjacent positions of a heterocyclic pharmacophore, which is responsible for the essential competitive binding to the iron atom of the heme cofactor in the active site of CYP51. Most of these active ingredients are either imidazole derivatives (e.g., the fungicide prochloraz (7) and the antifungal clotrimazole (8)) or triazole derivatives (e.g., the fungicide cyproconazole (9) and the antifungal fluconazole (10)), but also other heterocycles have been used as pharmacophores of DMIs, such as pyridines and pyrimidines (e.g., fenarimol (11)) in crop protection and recently also tetrazoles in medicine (e.g., oteseconazole (12)). The very first 14α-demethylase inhibitors to be commercialized were the antifungal miconazole (6) in 1971 and the fungicide triadimefon in 1976. Since then, a whole arsenal of ca. 80 different 14α-demethylase inhibitors has entered the fungicide and antifungal markets. In each of the 5 past decades, several novel members of this mode of action class have been identified with improved potency, plant safety, patient compatibility, or broadened crop spectrum. Even today, novel active ingredients of this type are being developed and commercialized, such as the fungicide mefentrifluconazole (market launch 2019) and the antifungal isavuconazole (market launch 2015). It is amazing that 50 years after the market launch of the first member of this mode of action class, the 14α-demethylase inhibitors still play this dominating role in pharmacy and crop protection (Figure 2)—especially because the development of resistance did not spare the DMIs37−39 and azoles.39−41 The shift of sensitivity based on point mutations in the amino acid sequence of the CYP51 gene is different for the different pathogens and also impacts the diverse active ingredients, but not in the same manner, as there are different cross-resistance patterns. Furthermore, the extensive application of 14α-demethylase inhibitors in agriculture is suspected to impact the azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus(42) and the genetic stability and metabolic variability of Candida spp.(43) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Different pharmacophore types among 14α-demethylase inhibitors.

Latest Trends in Agrochemical Fungicide Research

The spread of resistant isolates in fungal field populations has impacted the performance of not only the above-mentioned DMIs but also other major fungicide classes, such as strobilurins,44 SDHIs,45 phenylamides,46 and carboxylic acid amide (CAA) fungicides.47 This means that there is a constant need for new solutions to control plant-pathogenic fungi. Research-based agrochemical companies currently address this problem with cutting-edge tools, such as structure- and target-based design,48 inverse design,49 and multi-parameter optimization.50 Such accelerated and focused innovation51 is achieved within the following three different approaches.

1. The Search for Novel Fungicidal Modes of Action Goes On: It Is Still Possible to Find Some

The whole arsenal of fungicides currently available to farmers worldwide as a tool to protect their crops can be divided into altogether 52 different modes of action.52,53 These molecular targets emcompass all major physiological processes in fungi, such as nucleic acid metabolism, cytoskeleton and motor proteins, respiration, amino acid and protein synthesis, signal transduction, lipid synthesis, transport and membrane integrity, melanin biosynthesis in cell walls, sterol biosynthesis in membranes, and cell wall biosynthesis. Some of these 52 different modes of action are covered by broad-spectrum fungicides, such as the Complex III inhibiting strobilurins, which are able to control pathogens from the phyla of Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Oomycota. Other modes of action are limited to specific groups of fungi, such as the oomycetes-selective RNA-polymerase-inhibiting phenylamides and cellulose-synthase-inhibiting CAA fungicides, or to specific crop plants, such as the melanin biosynthesis inhibitors which are specifically rice fungicides. Besides the already-mentioned market-dominating 14α-demethylase inhibitors, there are also some other modes of action which have been exploited in both medicinal and agricultural chemistry. Three such molecular targets belong to the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway as well. Δ8-Δ7-isomerase and Δ14-reductase are both inhibited by the fungicide class of morpholines, such as fenpropimorph, but also by the antifungal amorolfine.54 The successful antifungal target squalene epoxidase is listed by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC)53 as fungicidal mode of action as well, but the allylamines naftifine and terbinafine are too UV-instable to be used as agrochemicals.55 Also, inhibitors of cytochrome bc1 (the Complex III of the fungal respiratory chain) are known in both industries, the strobilurins are very important fungicides,56 and the natural product ilicicolin H is known to possess antifungal activity.57 A minor important antimycotic mode of action with uses as both fungicide and antifungal are naturally occurring chitin synthase inhibitors, such as polyoxin D and nikkomycin Z.58 Although the number of available antimycotic modes of actions in crop protection is much bigger than in medicine, huge efforts are still undertaken to discover additional novel fungicide modes of action.

Some years ago, DuPont Crop Protection purchased from Tripos a diverse bis-amide library, which focused on a piperidinylthiazole carboxylic acid core. The phenylacetic amide derivative 13 showed some modest preventative activity against Phytophthora infestans and Pseudoperonospora cubensis, the causal agent of cucumber downy mildew, as well as some weak curative activity against Plasmopara viticola, the causal agent of grape downy mildew. It was especially this hint of systemicity which encouraged Bob Pasteris and colleagues to start a hit-to-lead approach with this compound. Three classical scaffold hopping manipulations led to the discovery of oxathiapiprolin (14). First, the chlorophenyl ring of 13 was replaced by a trifluoromethyl-substituted pyrazole, providing 14 with a 20-fold increase in fungicidal activity. Then, cyclization of the α-methylbenzyl moiety of 14 to a tetralin ring afforded 15 and an additional 50-fold potency enhancement. Finally, replacement of the amide function of 15 by a cyclic isoxazoline mimic delivered oxathiapiprolin (16) and another 10-fold increase in potency. Oxathiapiprolin—10 000 times more active than the original hit 13—is so far the youngest as well as the most potent commercialized oomycetes-selective fungicide and possesses a completely novel mode of action, which is linked to the inhibition of an oxysterol-binding protein. The introduction of this new product facilitates the control of devastating late blight and downy mildew diseases, which previously had suffered from the resistance problems of older, established modes of action (Figure 4).59−62

Figure 4.

Invention pathway of oxathiapiprolin (16).

More recently, a 4-(3,5-dimethylpyridazolyl)benzamide, also stemming from a library approach, attracted the attention of researchers at BASF, as it showed some weak but interesting activity against Botrytis cinerea, the causal agent of gray mold on several crop plants, and Zymoseptoria tritici, the causal agent of wheat leaf blotch. One of the many molecular changes Christian Winter and colleagues made to this compound was the replacement of the dimethylpyrazole ring by a trifluoromethyl-substituted 1,2,4-oxadiazole. This manipulation resulted in the discovery of histone deacetylase inhibiting fungicides with strength against Phakopsora pachyrizhi, the causal agent of Asian soybean rust, and the identification of flufenoxadiazam, the first agrochemical developmental product with this mode of action.63,64 Similar histone deacetylase inhibitors bearing the same CF3-oxadiazole motif have been reported to possess anticancer efficacy,65 whereas specific hydroxamic acid derivatives also targeting a histone deacetylase are known to have antifungal activity in combination with fluconazole.66 Also, other novel modes of action are currently in the starting blocks to reach the fungicide market, as there is lots of movement in the agrochemical pipeline. With aminopyrifen, for the first time an inhibitor of GWT-1, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored transfer protein, has been announced as a fungicide:67,68 manogepix and its prodrug fosmanogepix are new antifungals with the same mode of action.69

The recently presented developmental product pyridachlometyl possesses a completely novel antitubulin mode of action.70 Furthermore, the two structurally related quinoline fungicidal developmental products, quinofumelin and ipflufenoquin, seem to possess a novel mode of action, which is eventually linked to the reduction of deoxynivalenol production.71,72 Also the recently actively patented class of phenylamidines seems to possess an unknown mode of action.73

2. Expanding Scope and Application of Formerly Less Significant Mode of Action Classes

Another possibility to reach somehow a novel mode of action is to take an existing one, which was limited so far to only a few target pathogens and crop plants or to a specific application method, and broaden its scope to a much wider use. Two recent examples show that this can be a very successful approach for fungicides.

A textbook example of how a neglected niche mode of action can become one of the most important fungicide classes with blockbuster products involves the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs), which block Complex II in the fungal respiratory chain. Carboxin (2), the very first SDHI, was commercialized in 1966 as a seed treatment agent against smuts and bunts on cereal seeds such as barley, wheat, and oats, but it never became a significant product. In the 1970s, the closely related anilides benodanil (17) and fenfuram (18), in which carboxin’s oxathiine acid moiety has been replaced by a benzoic acid and a furan carboxylic acid, respectively, reached the market. They possessed a rather limited seed care potential, similar to that of carboxin (2). Mepronil (19) and flutolanil (20), two active ingredients from the next generation of SDHIs, which were launched in the 1980s, introduced a substituent in the aniline portion as an important structural element of SDHIs. They are still used as seed treatment agents but also an additional use in foliar spray against Basidiomycetes such as Rhizoctonia solani, the causal agent of damping-off disease of different crop plants—the first time new avenues for SDHIs. In the 1990s, thifluzamide (21) and penthiopyrad (22) appeared on the fungicide market. Both products were among the first SDHIs with an ortho-substituent in the aniline moiety, a structural feature which proved to be crucial for optimum potency. Indeed, their fungicidal activity was higher than that of SDHIs from the previous decades, but their biological spectrum was still rather narrow, again mainly limited to the control of Rhizoctonia species. It was finally the 2000s which brought a big breakthrough for this until then under-used mode of action. Boscalid (23) and penthiopyrad (24), which both possess a larger substituent in the aniline or aminothiophene ortho-position, demonstrated that, surprisingly, SDHIs can control a broad range of fungal diseases also caused by Ascomycetes, such as molds, scabs, leaf spots, powdery mildew, brown rot, and early blight. Penthiopyrad’s trifluoromethylated pyrazole acid portion guided the way to the final optimization within the SDHIs in the 2010s. The difluoromethylated pyrazole carboxamides fluxapyroxad (25) and benzovindiflupyr (26) are highly active foliar fungicides against a whole spectrum of plant pathogens and have demonstrated their blockbuster potential. Nobody who knew the narrow scope of carboxin, benodanil, and fenfuram in the 1960s and 1970s would have guessed what a huge potential this mode of action would finally set free. The research departments of at least 10 different agrochemical companies contributed to this success story (Figure 5).74−78

Figure 5.

Evolution of succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHIs) from a small niche product to blockbuster products.

Another example for successful expansion of the pathogen scope of a mode of action comprises the quinone-inside inhibitors (QiIs), which bind to one of the different target sites of cytochrome bc1 (Complex III in the respiration chain). After the market launch of the oomycetes-selective fungicides cyazofamid79 in 2001 and amisulbrom80 in 2008, there was the general perception that this mode of action would only be applicable against downy mildew diseases. Very recently, fenpicoxamid,81 a semisynthetic derivative of the natural product UK-2A, and its fully synthetic analog florylpicoxamid82−84 have proven that many more pathogens from the phyla of Ascomycota, especially those causing leaf spot diseases, can be controlled.

3. Design of Resistance Breakers within Established Mode of Action Classes

In principle, there are two methods available to win the race against the constant spread of new resistant mutants among plant-pathogenic fungi. One is, of course, to identify novel modes of action and to enable their application in agriculture (see section 1). But there is also a second possibility, which attracts a lot of attention these days in the research departments of the crop protection industry. This is the design of resistance-breaking active ingredients within a mode of action class which suffers from resistance issues.

A recent success story of this approach is the discovery of metyltetraprole (27), a novel Complex III inhibitor binding to the Qo site of cytochrome bc1. It has been intentionally designed to control fungal populations with a G143A mutation, which is currently the major occurring strain of several leaf spot pathogens in Europe. After 25 years of strobilurin usage, a good portion of the European field population of Z. tritici, the causal agent of wheat leaf blotch and an economically important pathogen, developed resistance toward this fungicide class. These sensitivity issues are mainly caused by a point mutation in the active site of cytochrome bc1, during which a glycine is replaced by an alanine at amino acid position 143 (G143A). Metyltetraprole (27) is able to overcome these resistance problems, although it is still binding to the Qo site of Complex III, because its tetrazolinone pharmacophore is not impacted by a steric clash with the alanine of the mutated binding site like the methoxyacrylate and oximinoester or -amide pharmacophores of the classical strobilurins (Figure 6).85−88

Figure 6.

Metyltetraprole (27) avoiding the steric clash of azoxystrobin’s (28) methoxy group with the mutated alanine (see red circle) in the Qo site of G143A cytochrome bc1, based on docking studies on a Z. tritici homology model.

A second application of this strategy is currently ongoing with Complex III inhibiting soybean rust fungicides. Similar to Z. tritici and its G143A mutation after extensive strobilurin use, also P. pachyrhizi, the causal agent of Asian soybean rust, has developed a major sensitivity shift toward Qo inhibitors based on an F129L mutation. Also here, the design of resistance breakers is currently in full swing, because several research-based companies are searching for a solution to circumvent this resistance problem.89

In conclusion, fungicides have undoubtedly changed farming practices over the past 150 years, playing then and now a vital role in controlling the growth and reproduction of many different plant pathogens. Each key innovation in the history of agrochemical fungicides has been rapidly incorporated into agriculture and helped farmers in their efforts to produce a wide variety of different crops in a sustainable manner, with minimal impact on the environment, thereby safeguarding food security for a steadily growing population. Currently, the research-based agrochemical industry addresses with three different strategies the necessity to provide also in the future efficient fungicides to the farmers for the protection of their crop plants from fungal infestations. First, it still seems possible to discover fungicides with a novel, so far unexploited, and therefore resistance-unaffected mode of action, because in each of the previous decades including the current one, products with a new mode of action were launched into the crop protection market. Second, older modes of action which delivered only a few, commercially not significant niche products are revisited, as recent examples show that it may be possible to expand their biological spectrum and scope. Third, if the efficiency of a mode of action class suffers from fungal resistance and the structure of the molecular target, also with respect to the mutation of the resistance fungal strain, is known, then the design of resistance-breaking active ingredients is an option. As agrochemical fungicides undoubtedly constitute an unexploited potential for drug discovery,90 all three strategies can be applied to the search for novel antifungals and could potentially revitalize the pharmaceutical portfolio against human–pathogenic fungi.

Acknowledgments

The author is very grateful to Dr. Stefano Rendine for preparing Figure 6.

The author declares no competing financial interest.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Prof. Dr. Dieter Klemm, great mentor and internist, on the occasion of his 90th birthday.

References

- Lamberth C.; Rendine S.; Sulzer-Mosse S.. Agrochemical disease control: the story so far. In Recent Highlights in the Discovery and Optimization of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Mangelinckx S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2021; pp 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Klittich C. J. Milestones in fungicide discovery: Chemistry that changed agriculture. Plant Health Progress 2008, 9, 1. 10.1094/PHP-2008-0418-01-RV. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morton V.; Staub T. A short history of fungicides. APSnet Features 2008, online 10.1094/APSnetFeature-2008-0308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell P. E. A century of fungicide evolution. J. Agric. Sci. 2005, 143, 11–25. 10.1017/S0021859605004971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth C. Sulfur Chemistry in Crop Protection. J. Sulfur Chem. 2004, 25, 39–62. 10.1080/17415990310001612290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth W.A Treatise on the Culture and Management of Fruit Trees. Nichols and Son: London, 1802. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. On the Mildew and some other Diseases incident to Fruit Trees. Transact. Hort. Soc. 1824, 5, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Schlör H.Chemie der Fungizide. In Chemie der Pflanzenschutz- und Schädlingsbekämpfungsmittel; Wegler R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1970; Vol. 2, pp 44–161. [Google Scholar]

- Millardet P. A. Traitement du Mildiou par le Melange de Sulphate de Cuivre et de chaux. J. Agr. Prat. 1885, 2, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Masson E. Nouveau Procede Bourguignon Contre le Mildiou. J. Agr. Prat. 1887, 51, 814–816. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker H. D. Colloidal copper hydroxide as a fungicide. Indust. Eng. Chem. 1923, 15, 1177–1178. 10.1021/ie50167a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiei M.; Peyton L.; Hashemzadeh M.; Foroumadi A. History of the development of antifungal azoles: a review on structures, SAR and mechanism of action. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 104, 104240. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattif A. A.; Swindell K.. History of antifungals. In Antifungal Therapy; Ghannoum M. A., Perfect J. R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2009; pp 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Maertens J. A. History of the development of azole derivatives. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 1–10. 10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. B. History of antifungals. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1990, 23, 776–778. 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70286-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A. B.; Ronnest M. H.; Larsen T. O.; Clausen M. H. The chemistry of griseofulvin. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 12088–12107. 10.1021/cr400368e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjaervik E.; Zotchev S. B. Biosynthesis of the polyene macrolide antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 67, 436–443. 10.1007/s00253-004-1802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepser M. The value of amphotericin B in the treatment of invasive fungal infections. J. Crit. Care 2011, 26, 225.e1–225.e10. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill A. W. Miconazole: a historical perspective. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2006, 4, 171–175. 10.1586/14787210.4.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund . www.unfpa.org/data/world-population-dashboard (accessed February 2022).

- Cassidy E. S.; West P. C.; Gerber J. S.; Foley J. A. Redefining agricultural yields: from tonnes to people nourished per hectare. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 034015. 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi C.; Lamberth C.. New paradigms in crop protection research: registrability and cost of goods. In Discovery and Synthesis of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Stevenson T. M., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2015; pp 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Oerke E.-C.; Dehne H.-W. Safeguarding production – losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop Protect. 2004, 23, 275–285. 10.1016/j.cropro.2003.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. C.; Gurr S. J.; Cuomo C. A.; Blehert D. S.; Jin H.; Stukenbrock E. H.; Stajich J. E.; Kahmann R.; Boone C.; Denning D. W.; Gow N. A. R.; Klein B. S.; Kronstad J. W.; Sheppard D. C.; Taylor J. W.; Wright G. D.; Heitman J.; Casadevall A.; Cowen L. E. Threats posed by the fungal kingdom to humans, wildlife and agriculture. mBio 2020, 11, e00449. 10.1128/mBio.00449-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AgbioInvestor, AgbioCrop . The Crop Protection Industry Report, Products 2019, December 2020.

- Fortune Business Insights . Industry Reports, Antifungal Drugs Market 2019, May 2020.

- Howard K. C.; Dennis E. K.; Watt D. S.; Garneau-Tsodikova S. A comprehensive overview of the medicinal chemistry of antifungal drugs: perspectives and promise. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2426–2480. 10.1039/C9CS00556K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N.; Tu J.; Dong G.; Wang Y.; Sheng C. Emerging new targets for the treatment of resistant fungal infections. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5484–5511. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campoy S.; Adrio J. L. Antifungals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 86–96. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. D.; Denning D. W.; Gow N. A. R.; Levitz S. M.; Netea M. G.; White T. C. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 165rv13. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel K.; Vors J.-P.. Sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds, 3rd ed.; Jeschke P., Witschel M., Krämer W., Schirmer U., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2019; pp 797–844. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington P.Sterol biosynthesis inhibiting triazole fungicides. In Bioactive Heterocyclic Compound Classes: Agrochemicals; Lamberth C., Dinges J., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2012; pp 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kuck K. H.; Scheinpflug H.; Pontzen R.. DMI fungicides. In Modern Selective Fungicides; Lyr H., Ed.; Gustav Fischer: Jena, 1995; pp 205–258. [Google Scholar]

- Allen D.; Wilson D.; Drew R.; Perfect J. Azole antifungals: 35 years of invasive fungal infection management. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 787–798. 10.1586/14787210.2015.1032939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeres J.; Meerpoel L.; Lewi P. Conazoles. Molecules 2010, 15, 4129–4188. 10.3390/molecules15064129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirngibl L.Antifungal Azoles; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Price C. L.; Parker J. E.; Warrilow A. G. S.; Kelly D. E.; Kelly S. L. Azole fungicides – understanding resistance mechanisms in agricultural fungal pathogens. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1054–1058. 10.1002/ps.4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools H. J.; Hawkins N. J.; Fraaije B. A. Constraints on the evolution of azole resistance in plant pathogenic fungi. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 36–42. 10.1111/ppa.12128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. E.; Warrilow A. G. S.; Price C. L.; Mullins J. G. L.; Kelly D. E.; Kelly S. L. Resistance to antifungals that target CYP51. J. Chem. Biol. 2014, 7, 143–161. 10.1007/s12154-014-0121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley S. G.; Berkow E. L.; Rybak J. M.; Nishimoto A. T.; Barker K. S.; Rogers P. D. Azole antifungal resistance in Candida albicans and emerging non-albicans Candida species. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2173. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canuto M. M.; Rodero F. G. Antifungal drug resistance to azoles and polyenes. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002, 2, 550–563. 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00371-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer V. S.; Rezende C. P.; Pessoni A. M.; De Paula R. G.; Rangappa K. S.; Nayaka S. C.; Gupta V. K.; Almeida F. Antifungal agents in agriculture: friends and foes of public health. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 521. 10.3390/biom9100521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potocki L.; Baran A.; Oklejewicz B.; Szpyrka E.; Podbielska M.; Schwarzbacherova V. Synthetic pesticides used in agricultural production promote genetic instability and metabolic variability in Candida spp. Genes 2020, 11, 848. 10.3390/genes11080848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisi U.; Sierotzki H.; Cook A.; McCaffery A. Mechanisms influencing the evolution of resistance to Qo inhibitor fungicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 859–867. 10.1002/ps.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierotzki H.; Scalliet G. A review of current knowledge of resistance aspects for the next-generation succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 880–887. 10.1094/PHYTO-01-13-0009-RVW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisi U.; Cohen Y. Resistance to phenylamide fungicides: a case study with Phytophthora infestans involving mating type and race structure. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1996, 34, 549–572. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.34.1.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum M.; Waldner M.; Olaya G.; Cohen Y.; Gisi U.; Sierotzki H. Resistance mechanism to carboxylic acid amide fungicides in the cucurbit downy mildew pathogen Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1211–1214. 10.1002/ps.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth C.; Jeanmart S.; Luksch T.; Plant A. Current challenges and trends in the discovery of agrochemicals. Science 2013, 341, 742–746. 10.1126/science.1237227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenta M. Chemistry 4.0: how the digital revolution is changing chemical research. Chimia 2021, 75, 211–212. 10.2533/chimia.2021.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segall M. D. Multi-parameter optimization: identifying high quality compounds with a balance of properties. Curr. Pharm. Design 2012, 18, 1292–1310. 10.2174/138161212799436430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassayre J. Crop protection chemistry: innovation with purpose. Chimia 2021, 75, 561–563. 10.2533/chimia.2021.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann D.; Stenzel K.. FRAC mode-of-action classification and resistance risk of fungicides. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds, 3rd ed.; Jeschke P., Witschel M., Krämer W., Schirmer U., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2019; pp 589–608. [Google Scholar]

- The Fungicide Resistance Action Committee, https://www.frac.info (accessed February 2022).

- Lamberth C.Morpholine fungicides for the treatment of powdery mildew. In Bioactive Heterocyclic Compound Classes: Agrochemicals; Lamberth C., Dinges J., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2012; pp 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder N. S.; Mieth H.. Allylamine antifungal drugs. In Current Topics in Medical Mycology; Borgers M., Hay R., Rinaldi M. G., Eds.; Springer: New York, 1992; pp 158–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter H.; Steglich W.; Anke T. Strobilurins: evolution of a new class of active substances. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1328–1349. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. B.; Liu W.; Li X.; Chen T.; Shafiee A.; Card D.; Abruzzo G.; Flattery A.; Gill C.; Thompson J. R.; Rosenbach M.; Dreikorn S.; Hornak V.; Meinz M.; Kurtz M.; Kelly R.; Onishi J. C. Antifungal spectrum, in vivo efficacy and structure-activity relationship of ilicicolin H. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 814–817. 10.1021/ml300173e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz M. L.; Nunnally N.; Lockhart S. R.; Sexton D. J.; Berkow E. L. Antifungal activity of nikkomycin Z against Candida auris. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1495–1497. 10.1093/jac/dkab052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasteris R. J.; Hoffman L. E.; Sweigard J. A.; Andreassi J. L.; Ngugi H. K.; Perotin B.; Shepherd C. P.. Oxysterol-binding protein inhibitors: oxathiapiprolin – a new oomycete fungicide that targets an oxysterol-binding protein. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds, 3rd ed.; Jeschke P., Witschel M., Krämer W., Schirmer U., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2019; pp 979–987. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberth C. Agrochemical lead optimization by scaffold hopping. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 282–292. 10.1002/ps.4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasteris R. J.; Hanagan M. A.; Bisaha J. J.; Finkelstein B. L.; Hoffman L. E.; Gregory V.; Andreassi J. L.; Sweigard J. A.; Klyashchitsky B. A.; Henry Y. T.; Berger R. A. Discovery of oxathiapiprolin, a new oomycete fungicide that targets an oxysterol binding protein. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 354–361. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasteris R. J.; Hanagan M. A.; Bisaha J. J.; Finkelstein B. L.; Hoffman L. E.; Gregory V.; Shepherd C. P.; Andreassi J. L.; Sweigard J. A.; Klyashchitsky B. A.; Henry Y. T.; Berger R. A.. The discovery of oxathiapiprolin: a new, highly active oomycete fungicide with a novel site of action. In Discovery and Synthesis of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Stevenson T. M., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2015; pp 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Winter C.; Fehr M.. Discovery of the trifluoromethyloxadiazoles – a new class of fungicides with a novel mode of action. In Recent Highlights in the Discovery and Optimization of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Mangelinckx S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2021; pp 401–423. [Google Scholar]

- Winter C.; Fehr M.; Craig I. R.; Grammenos W.; Wiebe C.; Terteryan-Seiser V.; Rudolf G.; Mentzel T.; Quintero Palomar M. A. Trifluoromethyloxadiazoles: inhibitors of histone deacetylases for control of Asian soybean rust. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 3357–3368. 10.1002/ps.5874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobera M.; Madauss K. V.; Pohlhaus D. T.; Wright Q. G.; Trocha M.; Schmidt D. R.; Baloglu E.; Trump R. P.; Head M. S.; Hofmann G. A.; Murray-Thompson M.; Schwartz B.; Chakravorty S.; Wu Z.; Mander P. K.; Kruidenier L.; Reid R. A.; Burkhart W.; Turunen B. J.; Rong J. X.; Wagner C.; Moyer M. B.; Wells C.; Hong X.; Moore J. T.; Williams J. D.; Soler D.; Ghosh S.; Nolan M. A. Selective class IIa histone deacetylase inhibition via a nonchelating zinc-binding group. Nature Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 319–325. 10.1038/nchembio.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkovec J. M. Advances in antifungal drug development. Med. Chem. Rev. 2018, 53, 313–336. 10.29200/acsmedchemrev-v53.ch16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatamoto M.; Aizawa R.; Koda K.; Fukuchi T. Aminopyrifen, a novel 2-aminonicotinate fungicide with a unique effect and broad-spectrum activity against plant pathogenic fungi. J. Pestic. Sci. 2021, 46, 198–205. 10.1584/jpestics.D20-094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatamoto M.; Aizawa R.; Kobayashi Y.; Fujimura M. A novel fungicide aminopyrifen inhibits GWT-1 protein in glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor biosynthesis in Neurospora crassa. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 156, 1–8. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K. J.; Ibrahim A. S. Fosmanogepix: a review of the first-in-class broad spectrum agent for the treatment of invasive fungal infections. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 239. 10.3390/jof6040239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y.; Watanabe S.; Harada T.; Iwahashi F. Pyridachlometyl has a novel anti-tubulin mode of action which could be useful in anti-resistance management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 1393–1401. 10.1002/ps.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X.; Zhao H.; Xu H.; Li Z.; Wang J.; Song X.; Zhou M.; Duan Y. Antifungal activity and biological characteristics of the novel fungicide quinofumelin against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 2567–2574. 10.1094/PDIS-08-20-1821-RE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu Q.; Bi L.; Xu H.; Li T.; Zhou Z.; Li Z.; Wang J.; Duan Y.; Zhou M. Antifungal activity of quinofumelin against Fusarium graminearum and its inhibitory effect on DON biosynthesis. Toxins 2021, 13, 348. 10.3390/toxins13050348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand S.; Es-Sayed M.; Wachendorff-Neumann U.; Brunet S.. Halogen-substituted phenoxyphenylamidines and the use thereof as fungicides. WO 2016/202742 (Bayer Cropscience AG).

- Rheinheimer J.Succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors: anilides. In Modern Crop Protection Compounds, 3rd ed.; Jeschke P., Witschel M., Krämer W., Schirmer U., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2019; pp 681–694. [Google Scholar]

- Walter H.Fungicidal succinate dehydrogenase inhibiting carboxamides. In Bioactive Carboxylic Compound Classes: Pharmaceuticals and Agrochemicals; Lamberth C., Dinges J., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2016; pp 405–425. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L.; Shen Y.-Q.; Jiang L.-N.; Zhu X.-L.; Yang W.-C.; Huang W.; Yang G.-F.. Succinate dehydrogenase: an ideal target for fungicide discovery. In Discovery and Synthesis of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Stevenson T. M., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2015; pp 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Guan A.; Liu C.; Yang X.; Dekeyser M. Application of the intermediate derivatization approach in agrochemical discovery. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7079–7107. 10.1021/cr4005605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanase Y.; Yoshikawa Y.; Kishi J.; Katsuta H.. The history of complex II inhibitors and the discovery of penthiopyrad. In Pesticide Chemistry; Ohkawa H., Miyagawa H., Lee P. W., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2007; pp 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Mitani S.; Araki S.; Yamaguchi T.; Takii Y.; Ohshima T.; Matsuo N. Biological properties of the novel fungicide cyazofamid against Phytophthora infestans on tomato and Pseudoperonospora cubensis on cucumber. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 139–145. 10.1002/ps.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine S.; Remuson F.; Caddoux L.; Barres B. Investigation of the sensitivity of Plasmopara viticola to amisulbrom and ametoctradin in French vineyards using bioassays and molecular tools. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2115–2123. 10.1002/ps.5461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen W. J.; Yao C.; Myung K.; Kemmitt G.; Leader A.; Meyer K. G.; Bowling A. J.; Slanec T.; Kramer V. J. Biological characterization of fenpicoxamid, a new fungicide with utility in cereals and other crops. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 2005–2016. 10.1002/ps.4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. G.; Bravo-Altamirano K.; Herrick J.; Loy B. A.; Yao C.; Nugent B.; Buchan Z.; Daeuble J. F.; Heemstra R.; Jones D. M.; Wilmot J.; Lu Y.; DeKorver K.; DeLorbe J.; Rigoli J. Discovery of florylpicoxamid, a mimic of a macrocyclic natural product. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 50, 116455. 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. G.; Yao C.; Lu Y.; Bravo-Altamirano K.; Buchan Z.; Daeuble J. F.; DeKorver K.; DeLorbe J.; Heemstra R.; Herrick J.; Jones D.; Loy B. A.; Rigoli J.; Wang N. X.; Wilmot J.; Young D.. The discovery of florylpicoxamid, a new picolinamide for disease control. In Recent Highlights in the Discovery and Optimization of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Mangelinckx S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2021; pp 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Yao C.; Meyer K. G.; Gallup C.; Bowling A. J.; Hufnagl A.; Myung K.; Lutz J.; Slanec T.; Pence H. E.; Delgado J.; Wang N. X. Florylpicoxamid, a new picolinamide fungicide with broad spectrum activity. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4483–4496. 10.1002/ps.6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y.; Yoshimoto Y.; Arimori S.; Iwahashi F.. The discovery of metyltetraprole: reconstruction of the quinone outside inhibitor extended pharmacophore to overcome QoI-resistant strains. In Recent Highlights in the Discovery and Optimization of Crop Protection Products; Maienfisch P., Mangelinckx S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2021; pp 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y.; Kiguchi S.; Suemoto H.; Iwahashi F. Antifungal activity of metyltetraprole against the existing QoI-resistant isolates of various plant pathogenic fungi. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 1743–1750. 10.1002/ps.5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y.; Yoshimoto Y.; Arimori S.; Kiguchi S.; Harada T.; Iwahashi F. Discovery of metyltetraprole: identification of tetrazolinone pharmacophore to overcome QoI resistance. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115211. 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.115211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suemoto H.; Matsuzaki Y.; Iwahashi F. Metyltetraprole, a novel putative complex III inhibitor targets known QoI-resistant strains of Zymoseptoria tritici and Pyrenophora teres. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1181–1189. 10.1002/ps.5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y.; Tobita H.; Tamashima H.; Semba Y.. Method of controlling soybean rust fungus that is resistant to Qo inhibitors. WO 2020/027214 (/Sumitomo Chemical Company Ltd.).

- Jampilek J. Potential of agricultural fungicides for antifungal drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2016, 11, 1–9. 10.1517/17460441.2016.1110142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]