Abstract

The high incidence of antibiotic resistance and biofilm-associated infections is still a major cause of morbidity and mortality and triggers the need for new antimicrobial drugs and strategies. Nanotechnology is an emerging approach in the search for novel antimicrobial agents. The aim of this study was to investigate the inherent antibacterial effects of a self-assembling amphiphilic choline-calix[4]arene derivative (Chol-Calix) against Gram negative bacteria. Chol-Calix showed activity against Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, including antibiotic-resistant strains, and affected the bacterial biofilm and motility. The activity is likely related to the amphipathicity and cationic surface of Chol-Calix nanoassembly that can establish large contact interactions with the bacterial surface. Chol-Calix appears to be a promising candidate in the search for novel nanosized nonconventional antimicrobials.

Keywords: antibacterial, antibiofilm, motility inhibition, choline-calix[4]arene, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotic resistance

Diffusion of bacterial infections, low antibiotic turnover, and antibiotic resistance phenomena are serious problems and trigger a strong demand for novel strategies and materials that can manage with these issues. Nanotechnology is emerging as a sound approach to generate novel compounds as an alternative or complement to traditional antibiotics.1 Indeed, nanoantimicrobials might fill the gaps where traditional antibiotics fail and potentially revolutionize antimicrobial therapy. Compared with conventional antimicrobials, nanoantimicrobial compounds offer attractive advantages deriving from their chemical but also physical properties (size, shape) that may lead to fine-tuned interactions with bacterial cells. A nanoantimicrobial may amplify the contact with the bacterial cell surface and might penetrate the bacterium with modalities different from those of small molecules.2 Moreover, as reported for some ammonium quaternary compounds, the assembly in nanosized aggregates can result in multivalent antibacterial agents with reduced toxicity to eukaryotic cells.3

The applications of nanotechnology include both inorganic nanoparticles and organic nanoassemblies with intrinsic antibacterial properties or working as nanocarriers for the transport of antibiotics.4,5

Calix[n]arenes are a family of macrocyclic polyphenols of great interest in supramolecular chemistry.6 Because of the presence of a host cavity, synthetic versatility, and ability of amphiphilic derivatives to self-assembly in nanostructured systems, calix[n]arene oligomers have been proposed as molecular scaffolds in drug discovery7 and drug delivery.8 Calixarene derivatives have shown low cytotoxicity and immunogenicity9 and activity as antitumoral,10 synthetic vaccine,11 antimicrobial agents,12 and more. Antibacterial calixarene derivatives include polycationic,13 glycosylated,14 and polyanionic15 derivatives, other than calixarene-coating inorganic nanoparticles.16,17

The clustering and spatial organization of multiple bioactive groups on a macrocyclic calix[4]arene platform is a promising approach for developing novel antimicrobial agents that show higher antibacterial activity and lower toxicity to eukaryotic cells compared with monomeric analogues18,19 and known antiseptics.20 Previously, we demonstrated that the clustering of four N-methyldiethanol ammonium groups on a calix[4]arene scaffold provided a polycationic derivative that showed antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis, including methicillin-resistant strains, and in combination with old antibiotics enhanced the antibiotic effect against a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain.21

Among polycationic calixarenes, a choline-calix[4]arene derivative (Chol-Calix), bearing choline groups at the upper rim of a calix[4]arene scaffold and dodecyl alkyl chain at its lower rim (Figure 1), is an amphiphilic compound able to spontaneously self-assemble in stable micellar nanoaggregates.22,23

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of Chol-Calix, schematic representation of its self-assembly in a micellar nanoaggregate, and picture of the limpid nanoaggregate solution. Adapted with permission from ref (28). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

We previously demonstrated that Chol-Calix at low concentration (ca. 10 μM) in a biomimetic medium (10 mM PBS, pH 7.4) forms aggregates with a diameter of around 40 nm, a polydispersity index of 0.2, and a zeta potential of +24.7 mV.22 The Chol-Calix micellar nanoassemblies were shown be promising nanocarriers for poorly water-soluble and easily degradable drugs,24 old antibiotics (i.e., ofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline),25 and photoresponsive molecules eliciting photoinduced antibacterial activity due to the generation of nitric oxide and singlet oxygen radicals.22,26,27 The potential of Chol-Calix as a curcumin delivery system was also successfully proved in vivo, in animal models of uveitis28 and psoriasis.29,30

The antibacterial activity reported for polycationic calixarenes and for choline derivatives31 suggested that the nanosized Chol-Calix might also possess antibacterial properties. The quaternary ammonium and hydroxyl groups of the choline moieties exposed on the surface of the Chol-Calix micelle might establish electrostatic and hydrogen bond interactions with the bacterial membrane, and as ligands, the choline groups might bind choline transporters expressed on the surface of Escherichia coli(32) and P. aeruginosa.(33) Amphypathicity and the nanosize of Chol-Calix are further advantageous features for larger interactions with the bacterial surface. A limit of cationic antibacterial agents may be the toxicity to human cells and tissues, but we previously observed no significant toxicity of Chol-Calix on fibroblasts22 and corneal cells.28

With a view to discovering new antimicrobial compounds, here we investigated whether Chol-Calix possesses intrinsic antibacterial activity and affects bacterial biofilm and motility.

The susceptibility of bacteria to Chol-Calix was investigated on E. coli and P. aeruginosa strains by evaluation of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). The values reported in Table 1 were comparable with those of other cationic antibacterial calixarene derivatives18−21 and showed no significant differences between ATCC and carbapenemase producing P. aeruginosa DSM 102273 and ofloxacin-resistant P. aeruginosa 1 ocular isolate. The activity on resistant antibiotic strains enhances the appeal of Chol-Calix in the search for novel unconventional antimicrobials.

Table 1. Antimicrobial Activity of Chol-Calix.

| strains | MIC (μg/mL) | MBC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli ATCC 10536 | 18.8 | 18.8 |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027 | 9.4 | 18.8 |

| P. aeruginosa DSM 102273 | 18.8 | 18.8 |

| P. aeruginosa 1 ocular isolate | 9.4 | 18.8 |

The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria provides the cell with an effective permeability barrier against external noxious agents but is itself a target for antibacterial agents. It is plausible to hypothesize that, analogously to other polycationic calixarene derivatives,34 ammonium quaternary compounds,35 and choline derivatives,36Chol-Calix elicits its antibacterial action by disturbance of the bacterial membrane. The initial interactions between the positively charged Chol-Calix and the negatively charged lipopolysaccharides of the bacterial membrane may be followed by integration of the dodecyl lipophilic tails of Chol-Calix into the hydrophobic membrane core with consequent weakening and alteration of the outer membrane integrity. The involvement of the dodecyl chains, which also induce the formation of stable nanoaggregates with enhanced surface contact area, is supported by the higher antibacterial effect of Chol-Calix against E. coli and P. aeruginosa ATCC strains compared with that of analogue choline-calix[4]arenes bearing shorter propyl or octyl chains at the calix[4]arene lower rim.37

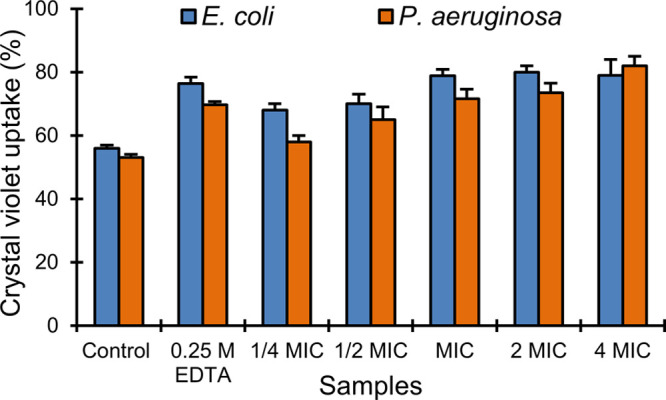

To obtain preliminary information about the mechanism of action, we performed a crystal violet assay,38 notoriously used to evaluate the membrane permeabilizing effect of antibacterial agents.39−41 Data in Figure 2 show that the uptake of crystal violet by E. coli and P. aeruginosa ATCC strains is enhanced from 56 and 53% (control) to 76.4 and 69.7% respectively, after treatment with EDTA, a known bacterial outer membrane permeabilizing agent (positive control). Analogously to EDTA, Chol-Calix enhanced the uptake of crystal violet in both E. coli and P. aeruginosa ATCC strains by 78.8 and 71.6%, respectively at the MIC concentration. The uptake values referred to the control were significant (p < 0.05) for all samples except for P. aeruginosa with Chol-Calix at 1/4 MIC. The absence of released intracellular material (data not shown), as indicated by no significant increase in the absorption at 260 nm in the supernatant of the bacterial cells treated with Chol-Calix, suggested that the activity is confined to the outer bacterial membrane.

Figure 2.

Crystal violet uptake assay. Percentage of crystal violet uptake by E. coli ATCC 10536 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027 alone (Control) and after treatment with EDTA and Chol-Calix at different concentrations.

Biofilms are microbial communities, held together by a self-produced extracellular matrix, very difficult to eradicate for their poor susceptibility to conventional antimicrobial agents.42 Having antimicrobial agents that are also active against biofilm is a considerable achievement. Therefore, we investigated the effect of Chol-Calix on biofilm formation and preformed biofilm.

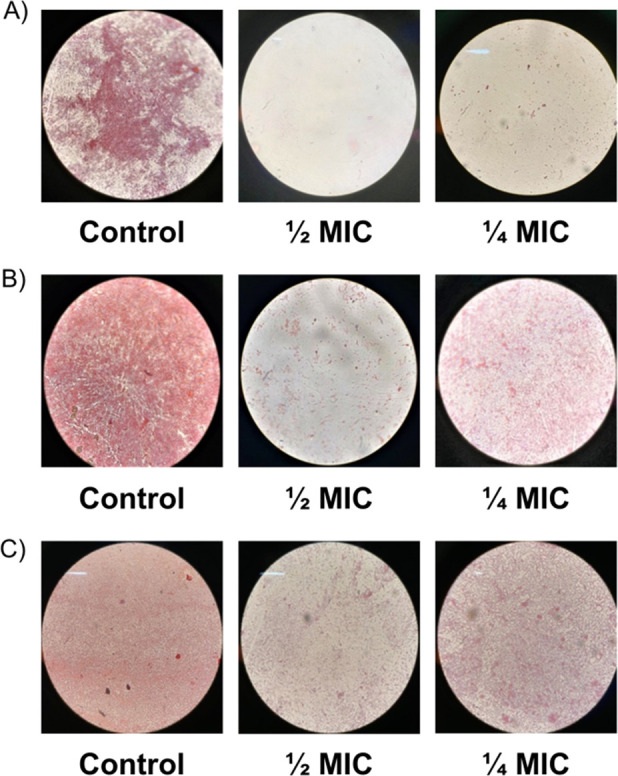

Concentrations of Chol-Calix lower than the MIC value poorly interfered with the planktonic growth of E. coli and P. aeruginosa, causing a slight decrease with respect to the control, although they caused significant (p < 0.05) antibiofilm activity (Figures 3 and 4 and Table S1). In particular, the antibiofilm effect of Chol-Calix was more evident on E. coli than on P. aeruginosa, with the inhibition of biofilm biomass at 1/2 MIC equal to 90.4 and 40–55%, respectively (Figure 3). Moreover, the results clearly demonstrate that 1/4 MIC and 1/8 MIC of Chol-Calix determined poor growth inhibition (14.5 and 1.8%), although it caused good biofilm inhibition (77.6 and 51%) of E. coli. These results were substantiated by observing bacterial biofilms under a light microscope (Figure 4). Direct microscopic observation showed that, after 24 h in the absence of Chol-Calix, bacterial cells formed evident biofilms. In the presence of concentrations of Chol-Calix equal to 1/2 and 1/4 MIC, bacterial cells grew as looser colonies and the amount of formed biofilm was reduced and was almost absent at 1/2 MIC for E. coli (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Reduction (%) of (A) E. coli ATCC 10536, (B) P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027, and (C) P. aeruginosa 1 ocular isolate planktonic growth and biofilm formation in the presence of various concentrations of Chol-Calix.

Figure 4.

Microscopic images of the biofilm formation inhibition of (A)E. coli ATCC 10536, (B) P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027, and (C) P. aeruginosa 1 ocular isolate in the presence of different concentrations of Chol-Calix.

Cationic compounds with both antibacterial and antibiofilm activity were reported.43−45 Mechanisms involved in bacterial biofilm formation are multiple and very complex and nowadays are not yet fully understood;46 therefore, establishing the exact antibiofilm mechanism of Chol-Calix is not trivial. However, the long dodecyl chains could play a role in the antibiofilm activity of Chol-Calix; indeed analogue choline-calix[4]arene derivatives, bearing shorter propyl and octyl chains, did not show antibiofilm activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa ATCC strains.36

We also evaluated the effect of Chol-Calix on preformed biofilms in terms of influence on biofilm biomass. The results documented that Chol-Calix was capable to reduce the preformed biofilm of both E. coli and P. aeruginosa ATTC and ofloxacin-resistant P. aeruginosa 1 ocular isolate (Figure 5, Table S2). For P. aeruginosa strains, a 37–50% reduction in preformed biofilm was detected at 2 MIC and 4 MIC (18.8 and 37.6 μg/mL) and 58–68% reduction at 8 MIC (75 μg/mL). For E. coli, a 66.5% reduction was detected at 8 MIC dose corresponding to 150 μg/mL. Compounds reducing preformed biofilm at concentration >100 μg/mL are present in literature.47,48 Furthermore, it is remarkable that the potency of Chol-Calix may be enhanced by loading an additional antibiofilm agent in the micellar structure, which can entrap active molecules including antibiotics.25

Figure 5.

Reduction (%) of preformed biofilm in the presence of various concentrations of Chol-Calix.

The disturbance of the bacterial cell membrane could be responsible for the activity on the biofilm as reported for a choline-based ionic liquid.49 Moreover, it is plausible thinking that, analogously to other micelles of quaternary ammonium salts,50Chol-Calix first adsorbs onto the biofilm surface through multicharged interactions, and then penetrates the extracellular polymeric matrix, diffuses throughout the biofilm, and reduces the biofilm biomass.

Motility is important for the survival, dissemination, and virulence of bacteria. Therefore, inhibiting the motility can be a way to attack pathogens.51 With this in mind, we decided to investigate whether Chol-Calix can affect the swarming, swimming, and twitching motility of E. coli and P. aeruginosa strains. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work investigating the effect of an antibacterial candidate built on a calixarene scaffold on bacterial motility.

Swarming is described as a social phenomenon involving the movement of bacteria across a semisolid surface.52 It is associated with enhanced virulence and antibiotic resistance of various human pathogens, including P. aeruginosa.53 Controlling swarming is of major interest for the development of novel anti-infectives. The pretreatment with Chol-Calix at sub-MIC concentrations (1/2 MIC) reduced swarming and twitching of approximately 50–60% on E. coli and P. aeruginosa, respectively. A different effect was instead observed on swimming motility; in fact, a weaker inhibition was observed for E. coli compared to P. aeruginosa (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Microscopic images showing the swarming, swimming, and twitching of E. coli ATCC 10536, P. aeruginosa ATCC 9027, and P. aeruginosa 1, without (control) and with pretreatment with Chol-Calix at sub-MIC concentration.

The effect of Chol-Calix on the biofilm formation and bacterial motility agreed with findings showing that in several Gram-negative bacteria, the motility is critical for both initial surface attachment and subsequent biofilm formation.

In conclusion, in this study, we proved that the nanoassembling Chol-Calix possesses intrinsic antibacterial activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa strains and affects bacterial biofilm and motility. The effective activity against antibiotic-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa as well makes Chol-Calix an appealing potential nanosized antibacterial agent. The combination of its intrinsic antibacterial activities with the previously demonstrated advantage as a nanocarrier for drug delivery opens possibilities for application in antibacterial combined multidrug therapy.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00015.

Materials, Chol-Calix synthesis and characterization (NMR, DLS, TEM), microbiological methods, tables reporting the values relative to the effect of Chol-Calix on planktonic growth, biofilm formation, and preformed biofilm (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the preparation of this manuscript, including the conception and design of the study (G.M.L.C., A.N.), Chol-Calix synthesis and characterization (G.M.L.C., G.Gr.), microbiological studies (G.Gi, A.M, G.T., A.N.), and writing and editing of the manuscript (G.M.L.C., A.N.). All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was originally published on May 10, 2022, with a typo in the title. The corrected version was reposted on May 11, 2022.

Supplementary Material

References

- Seil J. T.; Webster T. J. Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 2767–2781. 10.2147/IJN.S24805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzello L.; Cingolani R.; Pompa P. P. Nanotechnology tools for antibacterial materials. Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 807–821. 10.2217/nnm.13.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallemand F.; Daull P.; Benita S.; Buggage R.; Garrigue J.-S. Successfully improving ocular drug delivery using the cationic nanoemulsion, Novasorb. J. Drug Delivery 2012, 2012, 604204–16. 10.1155/2012/604204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyth N.; Houri-Haddad Y.; Domb A.; Khan W.; Hazan R. Alternative antimicrobial approach: Nano-antimicrobial materials. Evid-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 246012. 10.1155/2015/246012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abed N.; Couvreur P. Nanocarriers for antibiotics: A promising solution to treat intracellular bacterial infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 43, 485–496. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri P.; Sessler J. L.; Wang M.-X.. Calixarenes and Beyond; Springer:Berlin, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y.-C.; Hu X.-Y.; Guo D.-S. Biomedical applications of calixarenes: State of the art and perspectives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2768–2794. 10.1002/anie.201916380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Ding X.; Guo X. Assembly behaviors of calixarene-based amphiphile and supra-amphiphile and the applications in drug delivery and protein recognition. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 269, 187–202. 10.1016/j.cis.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naseer M. M.; Ahmed M.; Hameed S. Functionalized calix[4]arenes as potential therapeutic agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 89, 243–256. 10.1111/cbdd.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola S.; Consoli G. M. L.; Merlo S.; Drago F.; Sortino M. A.; Geraci C. Inhibition of rat glioma cell migration and proliferation by a calix[8]arene scaffold exposing multiple GlcNAc and ureido functionalities. J. Neurochem. 2008, 107, 1047–1055. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci C.; Consoli G. M. L.; Granata G.; Galante E.; Palmigiano A.; Pappalardo M.; Di Puma S. D.; Spadaro A. First self-adjuvant multicomponent potential vaccine candidates by tethering of four or eight muc1 antigenic immunodominant PDTRP units on a calixarene platform: Synthesis and biological evaluation. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24, 1710–1720. 10.1021/bc400242y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodik R. V. The antimicrobial and antiviral activity of calixarenes. J. Org. Pharm. Chem. 2015, 13, 67–78. 10.24959/ophcj.15.830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mourer M.; Duval R. E.; Constant P.; Daffé M.; Regnouf-de-Vains J.-B. Impact of tetracationic calix[4]arene conformation-from conic structure to expanded bolaform on their antibacterial and antimycobacterial activities. ChemBioChem. 2019, 20, 911–921. 10.1002/cbic.201800609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata G.; Stracquadanio S.; Consoli G. M. L.; Cafiso V.; Stefani S.; Geraci C. Synthesis of a calix[4]arene derivative exposing multiple units of fucose and preliminary investigation as a as potential broad-spectrum antibiofilm agent. Carbohydr. Res. 2019, 476, 60–64. 10.1016/j.carres.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamartine R.; Tsukada M.; Wilson D.; Shirata A. Antimicrobial activity of calixarenes. Chimie 2002, 5, 163–169. 10.1016/S1631-0748(02)01354-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid S.; Parveen S.; Shah M. R.; Rahim S.; Ahmed S.; Imran Malik M. Calixarene coated gold nanoparticles as a novel therapeutic agent. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 3988–3996. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2019.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tauran Y.; Coleman A. W.; Kim B. Bio-Applications of calix[n]arene capped silver nanoparticles. J. Nanosc. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 6308–6326. 10.1166/jnn.2015.10850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourer M.; Dibama H. M.; Fontanay S.; Grare M.; Duval R. E.; Finance C.; Regnouf-de-Vains J.-B. p-Guanidinoethyl calixarene and parent phenol derivatives exhibiting antibacterial activities. Synthesis and biological evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5496–5509. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukerb A. M.; Rousset A.; Galanos N.; Méar J.-B.; Thépaut M.; Grandjean T.; Gillon E.; Cecioni S.; Abderrahmen C.; Faure K.; Redelberger D.; Kipnis E.; Dessein R.; Havet S.; Darblade B.; Matthews S. E.; de Bentzmann S.; Guéry B.; Cournoyer B.; Imberty A.; Vidal S. Antiadhesive properties of glycoclusters against Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10275–10289. 10.1021/jm500038p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grare M.; Dibama H. M.; Lafosse S.; Ribon A.; Mourer M.; Regnouf-de-Vains J.-B.; Finance C.; Duval R.E. Cationic compounds with activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria: interest of a new compound compared with two older antiseptics, hexamidine and chlorhexidine. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 432–438. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consoli G. M. L.; Granata G.; Picciotto R.; Blanco A. R.; Geraci C.; Marino A.; Nostro A. Design, synthesis and antibacterial evaluation of a polycationic calix[4]arene derivative alone and in combination with antibiotics. Med. Chem. Commun. 2018, 9, 160–164. 10.1039/C7MD00527J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bari I.; Picciotto R.; Granata G.; Blanco A. R.; Consoli G. M. L.; Sortino S. A bactericidal calix[4]arene-based nanoconstruct with amplified NO photorelease. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 8047–8052. 10.1039/C6OB01305H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodik R. V.; Anthony A.-S.; Kalchenko V. I.; Mély Y.; Klymchenko A. S. Cationic amphiphilic calixarenes to compact DNA into small nanoparticles for gene delivery. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 1654–1664. 10.1039/C4NJ01395F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco R.; Bondì M. L.; Cavallaro G.; Consoli G. M. L.; Craparo E. F.; Giammona G.; Licciardi M., Pitarresi G.; Granata G.; Saladino P.; La Marca C.; Deidda I.; Papasergi S.; Guarneri P.; Cuzzocrea S.; Esposito E.; Viola S.. Nanostructured formulations for the delivery of silibinin and otheractive ingredients for treating ocular diseases. Patent WO/2016/055976, PCT/IB2015/057732.

- Migliore R.; Granata G.; Rivoli A.; Consoli G. M. L.; Sgarlata C. Binding affinity and driving forces for the interaction of calixarene-based micellar aggregates with model antibiotics in neutral aqueous solution. Front. Chem. 2021, 8, 626467. 10.3389/fchem.2020.626467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bari I.; Fraix A.; Picciotto R.; Blanco A. R.; Petralia S.; Conoci S.; Granata G.; Consoli G. M. L.; Sortino S. Supramolecular activation of the photodynamic properties of porphyrinoid photosensitizers by calix[4]arene nanoassemblies. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 105573–105577. 10.1039/C6RA23492E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bari I.; Granata G.; Consoli G. M. L.; Sortino S. Simultaneous supramolecular activation of NO photodonor/photosensitizer ensembles by a calix[4]arene nanoreactor. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 18096–18101. 10.1039/C8NJ03704C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granata G.; Paterniti I.; Geraci C.; Cunsolo F.; Esposito E.; Cordaro M.; Blanco A. R.; Cuzzocrea S.; Consoli G. M. L. Potential eye drop based on a calix[4]arene nanoassembly for curcumin delivery: Enhanced drug solubility, stability, and anti-inflammatory effect. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 1610–1622. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b01066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata G.; Petralia S.; Forte G.; Conoci S.; Consoli G. M. L. Injectable supramolecular nanohydrogel from a micellar self-assembling calix [4] arene derivative and curcumin for a sustained drug release. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2020, 111, 110842. 10.1016/j.msec.2020.110842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippone A.; Consoli G. M. L.; Granata G.; Casili G.; Lanza M.; Ardizzone A.; Cuzzocrea S.; Esposito E.; Paterniti I. Topical delivery of curcumin by choline-calix[4]arene-based nanohydrogel improves its therapeutic effect on a psoriasis mouse model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5053. 10.3390/ijms21145053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siopa F.; Figueiredo T.; Frade R. F. M.; Neto I.; Meirinhos A.; Reis C. P.; Sobral R. G.; Afonso C. A. M.; Rijo P. Choline-based ionic liquids: Improvement of antimicrobial activity. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 5909–5916. 10.1002/slct.201600864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ly A.; Henderson J.; Lu A.; Culham D. E.; Wood J. M. Osmoregulatory systems of Escherichia coli: Identification of betaine-carnitine-choline transporter family member BetU and distributions of betU and trkG among pathogenic and nonpathogenic isolates. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 296–306. 10.1128/JB.186.2.296-306.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek A. A.; Chen C.; Wargo M. J.; Beattie J. A.; Hogan D. A. Roles of three transporters, CbcXWV, BetT1, and BetT3, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa choline uptake for catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 3033–3041. 10.1128/JB.00160-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formosa C.; Grare M.; Jauvert E.; Coutable A.; Regnouf-de-Vains J.-B.; Mourer M.; Duval R. E.; Dague E. Nanoscale analysis of the effects of antibiotics and CX1 on a Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug-resistant strains. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 575. 10.1038/srep00575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhalifa S.; Jennings M. C.; Granata D.; Klein M.; Wuest W. M.; Minbiole K. P. C.; Carnevale V. Analysis of the destabilization of bacterial membranes by quaternary ammonium compounds: a combined experimental and computational study. ChemBiochem 2020, 21, 1510–1516. 10.1002/cbic.201900698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernak J.; Chwala P. Synthesis and anti-microbial activities of choline-like quaternary ammonium chlorides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 38, 1035–1042. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melezhyk I. O.; Rodik R. V.; Iavorska N. V.; Klymchenko A. S.; Mely Y.; Shepelevych V. V.; Skivka L. M.; Kalchenko V. I. Antibacterial properties of tetraalkylammonium and imidazolium tetraalkoxycalix[4]arene derivatives. Anti-Infect. Agents 2015, 13, 87–94. 10.2174/2211352513666150327002110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devi K. P.; Nisha S. A.; Sakthivel R.; Pandian S. K. Eugenol (an essential oil of clove) acts as an antibacterial agent against Salmonella typhi by disrupting the cellular membrane. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 107–15. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder S.; Yadav K. K.; Sarkar R.; Mukherjee S.; Saha P.; Haldar S.; Karmakar S.; Sen T. Alteration of Zeta potential and membrane permeability in bacteria: a study with cationic agents. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 672. 10.1186/s40064-015-1476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N.; Tan S.-n.; Cui J.; Guo N.; Wang W.; Zu Y.-g.; Jin S.; Xu X.-x.; Liu Q.; Fu Y.-j. PA-1, a novel synthesized pyrrolizidine alkaloid, inhibits the growth of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus by damaging the cell membrane. Journal of Antibiotics 2014, 67, 689–696. 10.1038/ja.2014.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sana S.; Datta S.; Biswas D.; Sengupta D. Assessment of synergistic antibacterial activity of combined biosurfactants revealed by bacterial cell envelop damage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) – Biomembranes 2018, 1860 (2), 579–585. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen I. Biofilm-specific antibiotic tolerance and resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 877–886. 10.1007/s10096-015-2323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S.; Liu Z.; Young A. W.; Mark S. L.; Kallen-bach N. R.; Ren D. Effects of Trp- and Arg-Containing Antimicrobial-Peptide Structure on Inhibition of Esche-richia coli Planktonic Growth and Biofilm Formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1967–1974. 10.1128/AEM.02321-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J. J.; Turner R. J.; Joo D. A.; Stan M. A.; Chan C. S.; Allan N. D.; Vrionis H. A.; Olson M. E.; Ceri H. Copper and quaternary ammonium cations exert synergistic bactericidal and antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2870–2881. 10.1128/AAC.00203-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwaśniewska D.; Chen Y. L.; Wieczorek D. Biological Activity of Quaternary Ammonium Salts and Their Derivatives. Pathogens 2020, 9, 459. 10.3390/pathogens9060459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R.; Tiwari M.; Donelli G.; Tiwari V. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilms: A focus on anti-biofilm agents and their mechanisms of action. Virulence 2018, 9, 522–554. 10.1080/21505594.2017.1313372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farha A. K.; Yang Q.-Q.; Kim G.; Zhang D.; Mavumengwana V.; Habimana O.; Li H.-B.; Corke H.; Gan R.-Y. Inhibition of multidrug-resistant foodborne Staphylococcus aureus biofilms by a natural terpenoid (+)-nootkatone and related molecular mechanism. Food control 2020, 112, 107154. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Z. L.; Awais R.; Harris M.; Raji B.; Hoffman B. C.; Baker D. L.; Jennings J. A. 2-Heptylcyclopropane-1-Carboxylic Acid Disperses and Inhibits Bacterial Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 645180. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.645180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrewsky M.; Lovejoy K. S.; Kern T. L.; Miller T. E.; Le V.; Nagy A.; Goumas A. M.; Iyer R. S.; Del Sesto R. E.; Koppisch A. T.; Fox D. T.; Mitragotri S. Ionic liquids as a class of materials for transdermal delivery and pathogen neutralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 13313–13318. 10.1073/pnas.1403995111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F.; He D.; Yu Y.; Cheng L.; Zhang S. Quaternary ammonium salt-based cross-linked micelles to combat biofilm. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 541–546. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.9b00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josenhans C.; Suerbaum S. The role of motility as a virulence factor in bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 291, 605–614. 10.1078/1438-4221-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindai K.; Nakade K.; Masuda K.; Sagawa T.; Kojima H.; Shimizu T.; Shingubara S.; Ito T. Adhesion and bactericidal properties of nanostructured surfaces dependent on bacterial motility. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 5673–5680. 10.1039/C9RA08282D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overhage J.; Bains M.; Brazas M. D.; Hancock R. E. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a complex adaptation leading to increased production of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 2671–2679. 10.1128/JB.01659-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.