Abstract

The neurobiology of addiction has been an intense topic of investigation for more than 50 years. Over this time, technological innovation in methods for studying brain function rapidly progressed, leading to increasingly sophisticated experimental approaches. To understand how specific brain regions, cell types, and circuits are affected by drugs of abuse and drive behaviors characteristic of addiction, it is necessary both to observe and manipulate neural activity in addiction-related behavioral paradigms. In pursuit of this goal, there have been several key technological advancements in in vivo imaging and neural circuit modulation in recent years, which have shed light on the cellular and circuit mechanisms of addiction. Here we discuss some of these key technologies, including circuit modulation with optogenetics, in vivo imaging with miniaturized single-photon microscopy (miniscope) and fiber photometry, and how the application of these technologies has garnered novel insights into the neurobiology of addiction.

Introduction

Despite the commonly held belief that addiction is a failure of moral agency [1, 2], a large body of human and animal studies have established neurobiological factors as powerful drivers of drug-seeking behavior and addiction [3–5]. Evidence supports that genetic heritability contributes to addiction risk, with roughly half of addiction vulnerability being heritable [6–8].

Early pioneering studies from Olds and Milner [9, 10] identified key brain regions involved in reward and reinforcement, which made apparent that discrete brain regions and projections underlie behaviors central to addiction. These early experiments were a major impetus for intense scientific interest in identifying the neural correlates of drug addiction. At the time, there were few techniques for modulating brain function, mainly consisting of targeted lesions, electrical stimulation, and drug microinjection [11–13]. These techniques were restricted by a lack of cell-type and projection specificity and poor temporal resolution. In the last two decades, the rapid development of novel approaches for precisely observing and manipulating neuronal activity has allowed for the study of neural circuits that regulate reward and motivated behaviors. In this review article, our goal is not to provide a comprehensive discussion of drug addiction research, but rather to highlight how modern techniques in neuroscience have been applied to study cellular and circuit mechanisms of drug addiction (Fig. 1). We will first discuss representative studies that utilized optogenetics for mapping and manipulating reward circuitry and examine their impacts on drug-induced synaptic plasticity and behavior. We aim to update and complement earlier excellent reviews on these topics [5, 14–17]. Next, we will review the application of microendoscopic (miniscope) imaging and fiber photometry of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECIs) and fluorescent biosensors in the context of drug addiction. We refer the reader to recent in-depth reviews that discuss the different in vivo fluorescent imaging techniques with an emphasis on their strengths and limitations [18, 19]. In addition, recent reviews have covered the development, optimization, properties, and applications of fluorescent biosensors for various neurotransmitters and modulators [20, 21]. Miniscope Ca2+ imaging of activity changes in various brain cell types in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases has been reviewed [22]; the present review will focus on the application of miniscope and fiber photometry techniques to study circuit mechanisms of reward and addiction.

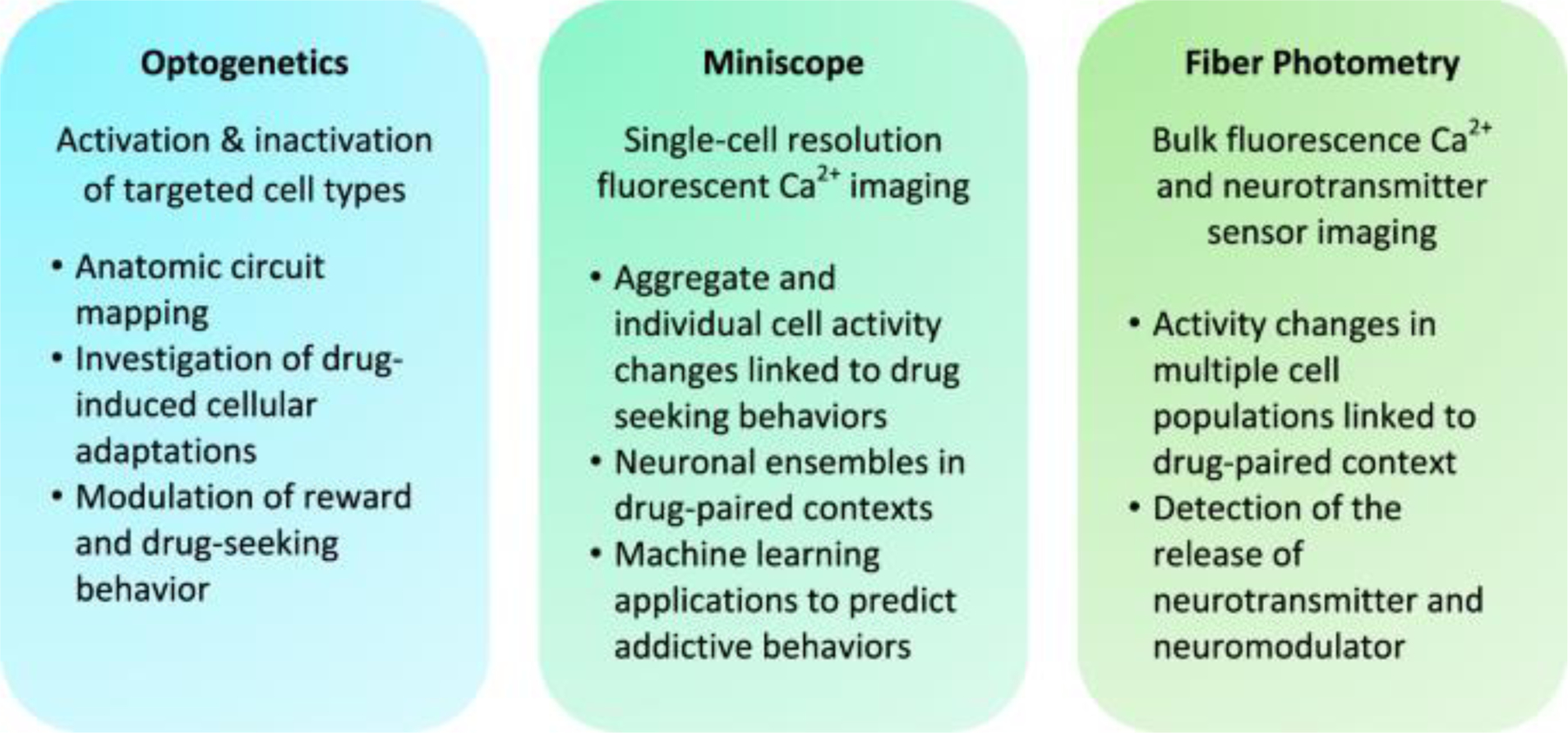

Fig. 1: In vivo optical tools for studying addiction neural circuitry.

Optogenetics, miniscope, and fiber photometry have distinct but complementary applications for manipulating and observing neural activity.

1. Optogenetics

One of the most remarkable accomplishments in the field of neuroscience has been the development of optogenetics, which, for the first time, allowed for the targeted modulation of defined cell types and projections in the brain, both in vitro and in vivo [23–25]. In optogenetics, light-sensitive ion channels or ion pumps are selectively expressed in cell populations of interest, followed by implantation of an optical fiber. Light of particular wavelengths delivered to the expressed construct through the optical fiber elicits ion flux that results in neuronal excitation or inhibition [26]. Over the last 20 years, many microbial opsins have been discovered and progressively engineered to optimize and customize a library of unique optogenetic constructs. These opsins have differing conductance magnitudes, ionic selectivity, kinetics, excitation spectra, and subcellular targeting profiles, thereby offering a diverse array of tools for investigating neural circuit function [26, 27]. The application of optogenetics has advanced our understanding of neural mechanisms of drug addiction on two major fronts: (1) anatomic circuit mapping with investigation of drug-induced cellular adaptations and (2) in vivo modulation of neural activity in behaving animals. In this section, we highlight several representative studies where these applications of optogenetics were leveraged to further elucidate addiction neurobiology.

1.1. Optogenetic circuit mapping

In optogenetic circuit mapping, opsins are expressed in a specific cell type, followed by photostimulation of axon terminals in the projection area, which induces postsynaptic currents in the receiving neurons [28]. Optogenetic circuit mapping has been instrumental in defining and characterizing the neurocircuitry of addiction [4, 29]. Central to this circuitry is the mesocorticolimbic pathway, consisting of dopaminergic projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and prefrontal cortex (PFC). Optogenetic circuit mapping has been used to delineate the cell-type and projection-specific organization of the mesocorticolimbic circuit, which was otherwise not possible with conventional electrophysiological approaches. Optogenetic circuit mapping challenged the dogma that the direct and indirect pathways of the NAc mirrored that of the dorsal striatum [30]. In the dorsal striatum, medium spiny neurons (MSNs) of the direct pathway almost exclusively express dopamine D1 receptors, whereas MSNs of the indirect pathway express dopamine D2 receptors [31]. Largely due to a lack of specific tools for assessing circuit connectivity, it was assumed that MSNs of the NAc were similarly segregated with regard to dopamine receptor type and projection target. Kupchik et al. [30] expressed channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2) in NAc D1- or D2-expressing MSNs of the NAc core and demonstrated that about half of the neurons in the ventral pallidum (VP)—canonically part of the indirect pathway—receive synaptic input from D1-MSNs. Further, they demonstrated that VP neurons that project directly to the thalamus receive input from both D1- and D2-MSNs. These results indicate that the NAc direct and indirect pathways are not simply defined by dopamine receptor expression nor by the effect on thalamic activation or inhibition. Similarly, optogenetic circuit mapping has provided a more nuanced understanding of the nature of projections from different subnuclei of the NAc to different cell types within the VTA [32, 33].

Although past research has focused on VTA dopamine neurons, recent studies have also revealed critical roles for VTA glutamate, GABA, and neurotransmitter co-releasing populations in the regulation of reward and aversion [34]. For example, optogenetics was used to demonstrate that VTA glutamate neurons project to numerous cell types within the NAc including parvalbumin GABAergic interneurons, MSNs, and cholinergic interneurons, and that they can regulate reinforcement-related behavior independent of dopamine [35–37]. Further, VTA glutamate/GABA co-releasing neurons project to the VP and lateral habenula, where they have opposing effects on neuronal activity due to differences in the relative strength of glutamatergic and GABAergic input [36].

In addition to mapping anatomic connections, optogenetics provides a means for investigating the cellular and synaptic adaptations that occur in the reward circuity after exposure to drugs of abuse. Animals with opsins expressed in defined circuits can be exposed to a drug, such as in a drug self-administration paradigm, followed by ex vivo electrophysiological recording of photostimulation-induced synaptic currents to identify the pathway-specific synaptic adaptations. This approach was used to study input-specific glutamatergic plasticity in the NAc, which plays a fundamental role in cocaine-seeking behavior [38, 39]. Although it was known that calcium-permeable AMPAR (CP-AMPAR) expression increases during the incubation of cocaine craving and contributes to drug seeking [40], it remained unknown whether specific inputs were differentially regulated during withdrawal. By expressing ChR2 in the basolateral amygdala (BLA), infralimbic (IL) cortex, or prelimbic (PrL) cortex, it was demonstrated that IL and BLA projections to the NAc underwent insertion of CP-AMPARs during the incubation period, whereas PrL to NAc projections underwent insertion of non-CP-AMPARs [41, 42]. Strikingly, cocaine self-administration led to the generation of NMDAR-expressing silent synapses in BLA-NAc, IL-NAc, and PrL-NAc synapses, which were subsequently unsilenced by AMPAR insertion during the incubation period. Optogenetics was also utilized to induce long-term depression (LTD) of these projections in vivo, which reversed the incubation-induced plasticity via removal of synaptic AMPARs and, depending on the pathway targeted, either promoted or reduced the incubation of cocaine craving. These representative studies demonstrate how optogenetics can serve as a powerful tool for both identifying the anatomical organization of neural circuits involved in addiction and for interrogating synaptic adaptations that occur with exposure to drugs of abuse or in unique behavioral contexts. Further, as illustrated by the studies that utilized optogenetics to induce LTD in vivo, optogenetic circuit modulation can be leveraged to investigate the role of discrete pathways and synaptic adaptations in regulating addiction-related behaviors.

1.2. Optogenetic circuit modulation in addiction

In vivo optogenetic manipulation can directly test how key cell types and pathways regulate reward processing and drug-seeking behavior. In addition, optogenetics can be used in creative ways to manipulate synaptic and circuit physiology that extends beyond simple activation or inhibition. In this section, we highlight representative studies that illustrate the application of optogenetics to investigate circuit mechanisms of drug seeking, incubation of drug craving, and triggered relapse.

A foundational observation in the study of addiction was that midbrain dopamine neurons encode reward prediction error, whereby their firing rate increases or decreases depending on the presence of a reward and the animal’s expectation for that reward [43, 44]. However, it was challenging to resolve whether these neurons drive reinforcement behavior without a means of selectively manipulating dopamine neurons. By specifically expressing ChR2 in VTA dopamine neurons, Tsai et al. [45] showed that in vivo optogenetic induction of phasic but not tonic action potential firing produced conditioned place preference (CPP) in mice. Further, optogenetic self-stimulation of VTA dopamine neurons was reinforcing [46, 47] and sufficient to induce addiction-like behavior, including cue-induced relapse and a persistence of self-stimulation despite paired foot-shock punishment [48]. Subsequent studies further demonstrated a central role of VTA dopamine neuron activation in drug-induced synaptic plasticity. Cocaine or morphine exposure induced the expression of CP-AMPARs in VTA dopamine neurons and in NAc MSNs, and optogenetic stimulation of VTA dopamine neurons alone mimicked this effect [48–50].

The major projection targets of VTA dopamine neurons are D1- and D2-MSNs in the NAc [51]. However, it was difficult to determine the discrete roles of these neurons prior to the advent of optogenetics, as they are interspersed throughout the NAc [52]. Implementation of optogenetic manipulation in D1- or D2-Cre transgenic mice has demonstrated that stimulation of NAc D1- and D2-MSNs had opposing effects on cocaine CPP; D1-MSN stimulation enhanced, whereas D2-MSN stimulation reduced cocaine CPP [53]. Similarly, optogenetic stimulation of dorsal striatal D1- and D2-MSNs induced reinforcement and aversion, respectively [54]. However, this dichotomy between D1- and D2-MSNs was challenged by findings that both MSN populations can promote reward or aversion depending on the pattern of optogenetic stimulation; brief stimulation promoted reinforcement and cocaine CPP, whereas prolonged stimulation promoted aversion [55]. Thus, optogenetics has revealed specific cell types and activity patterns that regulate reinforcement and drug reward in critical nodes of addiction circuitry.

Caveats should be considered when interpreting optogenetics experiments—particularly that optogenetic activation can induce a robust, artificial activation of neurons and projections that does not accurately mimic natural signaling patterns [56, 57]. Optogenetic inhibition provides an alternative approach for interrogating circuit function that can help determine the necessity of a pathway for a particular behavior. In an early optogenetics study, inhibition of neurons or axon terminals in the PrL or NAc core reduced both cocaine-primed and cue-induced reinstatement of drug seeking [58]. Another group showed that optogenetic inhibition of lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) to BLA projections disrupted cocaine-seeking induced by conditioned light and tone stimuli [59]. Both studies demonstrated that these projections are critical to reinstated cocaine seeking.

Lastly, an important extension of optogenetics has been to induce targeted manipulation of synaptic plasticity, particularly through the optogenetic depotentiation of specific pathways that underwent potentiation in addiction-related behavioral paradigms. An early study has shown that cocaine exposure potentiates excitatory transmission in the IL to NAc D1-MSN pathway, and that in vivo optogenetic depotentiation of this pathway reverses cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization [60]. Further, as referenced earlier, in vivo optogenetic LTD of NAc inputs from the BLA, IL, or PrL during withdrawal from cocaine self-administration reversed the “unsilencing” of these synapses that occurred during incubation of cocaine craving [41, 42]. Interestingly, depotentiation of inputs from the BLA and PrL inhibited incubation of cocaine craving, whereas depotentiation of input from the IL potentiated craving, thus highlighting how input-specific synaptic plasticity can have differential behavioral effects. Similarly, in vivo optogenetic reversal of cocaine-induced plasticity at the ventral hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) inputs to NAc D1-MSNs impaired response discrimination and reduced response vigor, respectively [61].

Recent studies have also demonstrated that in vivo optogenetic induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) can be used to induce targeted synaptic plasticity. Although NAc MSNs have been well studied in the context of addiction, the region also contains fast-spiking interneurons (FSIs) that can orchestrate the output of MSN ensembles through GABAergic inhibitory gating that suppresses motivated action [62]. In vivo LTP of excitatory BLA synapses to NAc FSIs increased inhibition of MSNs and expedited the acquisition of cocaine self-administration, indicating that this proportionally small interneuron population significantly modulates the output of NAc principal neurons [63]. These studies highlight the breadth of insights that can be garnered by in vivo optogenetic manipulation of both circuit activity and synaptic plasticity in behavioral models of addiction.

2. Biosensors for in vivo optical imaging

Observing neural activity in specific cell types and circuits in freely behaving animals is a powerful means for identifying and characterizing the neural correlates of addiction-related behavior. Our understanding of how these behaviors are encoded has been facilitated by recent developments in in vivo optical imaging techniques and indicators of neuronal activity or neurotransmitter release. We first review basic principles of these tools and technologies for in vivo imaging, then discuss how their application has led to advances in the study of addiction.

In the past decade, GECIs [64] and indicators for membrane voltage changes [65] have been developed to monitor neuronal activity in real-time (reviewed by ref. [66]. GCaMP6 has been the most widely used GECI, although additional GECIs continue to be developed with different fluorescence spectra, Ca2+ sensitivities, kinetics, and signal-to-noise ratios that can be tailored to experimental needs [66]. GECIs can be expressed in specific neuronal populations and their projections. For example, a double-floxed inverse open reading frame (DIO) or flip-excision (Flex) version of GCaMP can be expressed in select neuronal cell types using Cre-driver mice or rats, and fluorescent imaging can be performed at the level of the cell body or axon terminals. Promotor-driven GECI expression provides another method for cell-type-specific labeling. For example, the CaMKIIα promoter can drive GCaMP6 expression in forebrain excitatory neurons [67], whereas the mDlx promoter has been used to drive GCaMP6 expression in forebrain GABAergic interneurons [68]. Pathway-specific expression of indicators can also be achieved by injecting the retrogradely transported viral vector canine adenovirus-2 (CAV-2) [69] or recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vector rAAV2-retro [70] expressing Cre recombinase into a projection target together with injection of a Cre-dependent GECI into an upstream brain region. In vivo biosensor imaging can also be combined with optogenetics or electrophysiology in multi-modal experimental designs.

Numerous fluorescent biosensors have recently been developed for detecting the release of various neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, including dopamine [71, 72], norepinephrine [73], acetylcholine [74], and endocannabinoids [75], with extensive ongoing research to engineer novel biosensors. Recent comprehensive reviews have highlighted the development and application of these biosensors [21, 76]. Concurrently, advancements in methods for in vivo optical imaging, such as two-photon microscopy, single-photon miniaturized microscopy (miniscopes), and fiber photometry have enabled GECI and neurotransmitter biosensor imaging in behaving animals. Readers are directed to excellent reviews on details and comparisons of these techniques, including their advantages and limitations [18, 77]. In the following sections, we will highlight their applications within the drug addiction field.

3. Miniaturized single-photon microscopy

Miniscopes use gradient-index (GRIN) lenses to image hundreds of cells at single-cell resolution in behaving animals [78]. Similar to conventional fluorescence microscopy, a miniscope is equipped with an excitation light source (typically a 470 nm light-emitting diode), a dichroic mirror, objective lens, and a sensor to detect emitted light. Two key differences include the GRIN relay lens and the small footprint complementary metal oxide semiconductor sensor for detecting emitted light. Miniscopes provide several key advantages compared to other technologies for observing neural activity. Although electrophysiological microelectrode arrays are similarly capable of recording from tens to hundreds of neurons simultaneously, miniscope imaging of GECIs allows for the observation of activity from specific cell types and pathways. Two-photon microscopy can also accomplish this and allows for high-resolution imaging but is limited by its restriction to regions at or near the brain surface. In contrast, the use of microendoscopic lenses of varying lengths and diameters enables miniscope imaging in most brain regions. Although miniscopes detect greater background signal than two-photon microscopy, a comparison of these technologies showed highly correlated signal amplitudes as well as signal-to-noise ratios [79]. Miniscopes may also be less susceptible to brain motion due to faster acquisition frame-rates [80]. These and other advantages of miniscopes have allowed for novel insights into the neural mechanisms of drug addiction. For further technical details of miniscope design and function, readers are directed to other reviews [18, 77, 81].

Miniscope imaging of GECIs in brain regions implicated in addiction has emerged as a powerful tool to study the activity of specific cell types and pathways associated with drug reward and seeking. Here we discuss representative studies that utilized miniscopes to achieve this goal. We focus on the following applications: (1) study of changes in neuronal activity during distinct behaviors; (2) identification and investigation of functional neuronal ensembles; and (3) application of machine learning to decode behavioral state information represented in neural activity. To study changes in neuronal activity during drug-seeking behaviors, the frequency and pattern of Ca2+ transients can be quantified and linked to behavioral states. For example, miniscope imaging was used to investigate the activity of different cell types in the VP, a key output nucleus of the NAc, in a mouse model of cocaine self-administration [82]. GABAergic and glutamatergic VP neurons expressing GCaMP6f were imaged during extinction or cue-induced cocaine seeking; in aggregate, GABA neurons had increased activity during cued cocaine seeking, whereas glutamate neurons had increased activity during extinction learning. However, the responses of different GABA and glutamate neurons were heterogenous, as subpopulations of these neurons had distinct activity patterns that deviated from the aggregate signal. This study highlights how miniscopes can reveal both the aggregate and individual responses of specific cell types in distinct drug-seeking behaviors.

The implementation of miniscopes in freely moving animals also allows for correlation of neuronal activity with spatial positioning of the animal. The glutamatergic projection from the IL to the NAc has been thought to be an “anti-relapse” circuit that inhibits drug seeking [38, 83]. Miniscopes were used to observe the activity of NAc shell-projecting IL neurons in a rat model of cocaine self-administration [84]. The IL-NAc shell-projecting neurons were targeted by expressing CAV-2-Cre in the NAc shell and Cre-dependent GCaMP6f in the IL. IL-NAc shell neurons displayed reduced activity during active lever presses. The extent of inhibition in IL activity decreased between withdrawal day 1 and day 15, and correlated with increased drug seeking on day 15. Also, a large proportion of IL-NAc shell neurons were found to be spatially selective and to code for the animal’s location in the self-administration chamber without obvious bias to the locations of the active or inactive levers. Such spatial selectivity was significantly reduced during the incubation period, which could contribute to increased cocaine motivation.

Miniscopes have proven to be particularly beneficial for the study of neuronal ensembles in animal models of addiction. A neuronal ensemble can be defined as a group of neurons that is recruited during a particular behavioral task or neural computation, an idea first proposed by Semon [85] and further described by Donald Hebb [86, 87]. Techniques for studying neuronal ensembles historically have relied on post hoc immunostaining for cellular markers of neuronal activity, including cytochrome oxidase [88] and immediate early genes (IEGs) such as c-Fos and Arc [89]. These markers are expressed within minutes of increased neuronal activity and enable the functional mapping of activated neurons throughout the brain [90]. However, post hoc immunostaining for IEGs is limited by its low temporal resolution and requirement for sacrificing animals, which precludes the investigation of neural activity dynamics during behavior.

Although traditional approaches for studying neuronal ensembles have provided key insights into the distributed neuronal populations involved in addiction [91], miniscopes have allowed for the identification and observation of ensembles in behaving animals. In the dorsal striatum, miniscope imaging of GCaMP6s-expressing D1- or D2-MSNs was carried out in freely moving mice [92]. D1- and D2-MSN ensembles were identified and found to be spatially clustered within the dorsal striatum. Both D1- and D2-MSNs displayed increased activity after motion initiation and decreased activity after motion termination. Although cocaine increased locomotor activity, it did not result in increased activity of these neuron clusters. It did, however, alter the organization and connectivity of MSN clusters relative to normal locomotion [92]. Miniscope imaging of neuronal ensembles was also carried out to investigate how dorsal hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons encode contextual associations for nicotine place conditioning [93]. Although it is well-established that hippocampal “place cells” in the CA1 encode for spatial location in an environment and are essential for spatial learning and memory [94], the involvement of these neurons in drug-induced contextual conditioning remains incompletely understood. Miniscope imaging of CA1 pyramidal neurons in the dorsal hippocampus showed that nicotine place conditioning activates a unique CA1 neuronal ensemble, and that this ensemble was reactivated in the nicotine-paired context in the absence of nicotine. Further, activation of these CA1 neurons was necessary for the expression of nicotine place preference. This study demonstrates that CA1 ensembles integrate nicotine-contextual information for subsequent recall and are required for the reward-context association.

Although statistical analyses can correlate neural activity with behavior, machine learning approaches can further extend these conclusions to approach causality. In the aforementioned study on D1- and D2-MSN clusters in the dorsal striatum, a supervised machine learning algorithm (decision tree) was implemented to predict ambulation and non-ambulation states based on cluster activity [92]. The investigators compared algorithm predictions based on neural clusters, randomly selected groups of cells, and whole population activity, to show that the neural clusters indeed were responsible for encoding ambulation start and stop. Predictions can also be made for future behaviors. In an investigation of the involvement of the mPFC to dorsal periaqueductal gray projection (dPAG) in compulsive alcohol drinking, Ca2+ dynamics of these neurons during the initial alcohol experience on day 1 were shown to correlate with emergent drinking phenotypes 2 weeks later [95]. mPFC-dPAG neurons were most inhibited during alcohol drinking on day 1 in mice that later displayed a compulsive drinking phenotype; these mice continued to consume alcohol in the presence of a bitter deterrent 2 weeks later. A supervised machine learning algorithm (support vector machine classifier) was successfully trained on this data to predict the compulsive drinking phenotype, providing support for the idea that differences in neural activity can predispose to addiction-like behavior even with exposure to identical environmental conditions. As implemented in the above studies [92, 95], supervised machine learning methods train an algorithm on a set of data where the predicted variable is verified during training. However, unsupervised methods rely on no such a priori knowledge. Unsupervised machine learning methods have also been implemented on miniscope data to identify neural representations of behavioral states [96, 97].

Advancements in lens and miniscope technology, as well as computational analysis methods, have greatly expanded the scope of in vivo fluorescent imaging in recent years. Commercial products and open-source designs have been developed with various specifications customized to different applications, including wired and wireless models (for a comparison, see ref. [98]). Several newer advancements promise to aid the future investigation of addiction neural circuitry; cranial windows allow observation of dorsal cortical surfaces, GRIN lenses allow for visualization of subcortical and deeper brain regions [99], and multiple cortical layers can be visualized using an angled prism probe [100]. The compact NINscope (named after the institute of origin) is an open-source design with further reduced weight and footprint, which can be used to observe two separate brain regions in one mouse [101]. Two miniscopes have been used simultaneously in two different animals to measure the neural correlates of social interaction [102]. Miniaturized two-photon microscopy that enables imaging in freely-moving or head-fixed animals is also currently under development [103]; however, this method still requires expensive table-top equipment with limited portability. Finally, the Inscopix nVoke miniscope (Palo Alto, CA, USA) offers integrated optogenetic manipulation capability to confirm causal links in neural circuits [104]. Combined with rapidly advancing technologies, creative experimental design and innovative analysis methods will continue to allow miniscopes to resolve the cellular and network-level underpinnings of addiction.

4. Fiber photometry

Fiber photometry is used to observe and quantify fluorescence signals from cells expressing fluorescent indicators such as GECIs or fluorescent neurotransmitter biosensors, thereby providing a read-out of neural activity or neurotransmitter release. Unlike miniscopes, fiber photometry records an aggregate signal from groups of neurons near an implanted optical fiber. Dichroic mirrors and collimators direct excitation light of one or more wavelengths to an implanted optical fiber, and the emitted fluorescent signals are detected by photoreceivers. In order to discern signals from fluorophores with overlapping emission spectra, modulating the voltages driving excitation light with phase-offset frequencies is followed by signal demodulation with lock-in amplification [18, 81]. Isosbestic excitation (405 nm) is frequently used to control for artifacts arising from fiber bending and tissue autofluorescence. Alternatively, an activity-independent fluorophore such as green fluorescent protein (e.g., for jRGECO1a) or mCherry (e.g., for GCaMP) can be used as a control. Fiber photometry offers reduced technical and analytical complexity relative to miniscope imaging. It also decreases tissue damage when imaging deep brain regions, which can be advantageous for experiments that do not require single-cell resolution. Regardless, the two methods are highly complementary to each other [97]. Studies using fiber photometry or miniscopes that have particular relevance to addiction are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

Psychoactive drugs alter GCaMP activity and dopamine release in reward circuits of the brain.

| Alcohol | ↓ GCaMP6m, mPFC-dPAG; during initial alcohol exposure | [95] |

|

| ||

| GCaMP6f, dLight; differential activity patterns in subregional VTA-NAc projections | [117] | |

|

| ||

| Cocaine | ↓ GCaMP6m, VTA (DA) ↓ GCaMP6m, DRN (5-HT) |

[105] |

|

| ||

| ↑ GCaMP6f, NAc (D1-MSN); prior to entry into cocaine-paired chamber ↓ GCaMP6f, NAc (D2-MSN); after entry into cocaine-paired chamber |

[106] | |

|

| ||

| ↑ GCaMP6f, VP (GABA); cued cocaine seeking ↑ GCaMP6f, VP (Glu); extinction learning |

[82, 106] | |

|

| ||

| ↑ GCaMP6f, IL-NAc; withdrawal | [84] | |

|

| ||

| ↑ dLight, NAc | [116] | |

|

| ||

| GCaMP6s, dorsal striatum; altered organization and connectivity of MSN clusters | [92] | |

|

| ||

| Heroin | ↑ GCaMP6m, VTA (DA) | [105, 116] |

|

| ||

| ↑ GCaMP6m, DRN (5-HT) | [105] | |

|

| ||

| ↑ dLight, NAc | [116] | |

|

| ||

| MDMA | ↓ GCaMP6m, VTA (DA) ↓ GCaMP6m, DRN (5-HT) |

[105] |

|

| ||

| Methylphenidate | ↑ GRABDA, dorsal striatum | [71] |

|

| ||

| Morphine | ↑ dLight, NAc; intermittent dosing ↓ dLight, NAc; continuous dosing |

[115] |

|

| ||

| Nicotine | ↑ GCaMP6m, VTA (DA) | [105] |

|

| ||

| GCaMP6f, CA1; neural ensemble activated during CPP reactivated in the nicotine-paired context in the absence of nicotine | [93] | |

↑ Increase, ↓ decrease, DA dopamine, Glu glutamate, 5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine.

Traditionally, in vivo electrophysiology has been used to study how drugs of abuse affect neuronal activity. However, it remains challenging to determine the anatomical, morphological, or genetic identity of the recorded cells. Using fiber photometry, neuronal activity can be observed in genetically defined cell populations and specific projections. A straightforward yet illuminating study used fiber photometry to investigate how drugs with diverse mechanisms of action affect the activity of VTA dopamine and dorsal raphe nucleus serotonin neurons, which are key substrates that contribute to drug reinforcement [105]. Cocaine and 3,4-methylenedioxy methamphetamine both caused long-lasting suppression of dopamine and serotonin neuron activity, with both drugs similarly inhibiting these neurons via D2 or 5-HT1A autoreceptors. In contrast, heroin increased the activity of both cell populations, whereas nicotine activated only VTA dopamine neurons. This study highlights the utility of fiber photometry for investigating the mechanisms and time course of drug effects on specific cell populations of interest.

Similarly, a study utilized fiber photometry to investigate how D1- and D2-MSNs in the NAc core are affected by cocaine and associated environmental cues during cocaine CPP [106]. Baseline activity in D2-MSNs was greater than in D1-MSNs and cocaine administration inhibited D2- but enhanced D1-MSN activity. In test sessions after cocaine place preference conditioning, D1-MSN activity peaked just prior to mouse entry to the cocaine-paired chamber, whereas D2-MSN activity was suppressed immediately after entering the chamber. Notably, chemogenetic inhibition of D1-MSNs eliminated the increase in D1-MSN activity prior to entry into the cocaine-paired chamber and abolished the acquisition and expression of cocaine CPP. Thus, observation of neuronal activity linked to specific behaviors or environments can help elucidate the neural encoding of drug-paired contexts.

A powerful experimental approach is to identify neuronal activity patterns with fiber photometry, then modulate the activity of these neurons to determine their specific contribution to behavior. Particularly suitable for this is the combination of fiber photometry with optogenetics, which can re-create or inhibit specific firing patterns with temporal precision. Mice learned to lever press for optogenetic self-stimulation of VTA dopamine neurons and were later exposed to painful footshocks in association with light delivery; this addition of footshocks differentiated mice into two groups: “renouncers” that decreased lever pressing with footshocks and “perseverers” that continued to compulsively self-stimulate despite this punishment [107]. Previously, it was found that perseverers had significantly increased numbers of c-Fos-expressing cells in the OFC [48]. To better determine whether OFC activation contributes to the perseverant phenotype, fiber photometry was employed to record GCaMP6m fluorescence from OFC axon terminals projecting to the dorsal striatum. During punished sessions, GCaMP6m fluorescence increased around lever-press events in perseverers but decreased in renouncers. Critically, optogenetic inhibition of OFC neurons in persevering mice decreased punishment resistance, indicating that increased OFC-dorsal striatum activity underlies this compulsive behavior.

On the other hand, fiber photometry has been used to identify the consequences of behaviors induced by optogenetic stimulation. It was recently demonstrated that optogenetic stimulation of VTA dopamine neurons is itself sufficient to induce Pavlovian conditioning in the absence of natural rewards [108]. When light and tone cues were paired with phasic stimulation of VTA dopamine neurons, despite the absence of an external rewarding stimulus, the cues subsequently evoked conditioned locomotor responses and time-locked Ca2+ increases in dopamine neurons. These effects did not occur when cues and optogenetic stimulation were separated in time. These studies illustrate how multi-modal experimental approaches with fiber photometry and optogenetics can link changes in neuronal activity with behavioral outputs. A distinct advantage of fiber photometry is that it allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple fluorophores expressed in different cell types in the same brain region. One approach is to inject green and red fluorophores that are activated by Cre (Cre-On) or inactivated by Cre (Cre-Off) into Cre-driver mice in brain regions with heterogeneous cell populations [109]. Using this approach, GCaMP6f and jRGECO1a were expressed in direct- and indirect-pathway spiny projection neurons (SPNs) of the dorsal striatum in both D1-Cre (direct-pathway-specific) and A2A-Cre (indirect-pathway-specific) mice [110]. Strikingly, Ca2+ transients in direct- and indirect-pathway SPNs were highly synchronous within each hemisphere but were asynchronous across hemispheres. The magnitude of activation in the direct and indirect pathways coordinately determined the direction and vigor of movements. These results extend on an earlier study using only one fluorophore (GCaMP3), which determined that both direct and indirect pathways are activated during movement initiation but could not record activity from both pathways simultaneously [111]. Simultaneous imaging of direct- and indirect-pathway SPNs further illuminated how the relative magnitude of activity of these neurons predicts movement dynamics [110].

Microdialysis and voltammetry have traditionally been used to detect neurotransmitters and chemical substances in the brain in awake animals. In vivo microdialysis involves perfusing fluid into the brain using a probe with a semi-permeable membrane and then collecting dialysates for subsequent analysis [112]. Microdialysis, however, lacks temporal resolution and is labor-intensive. Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) is an electrochemical technique for detecting neurotransmitter release using a carbon fiber electrode [113]. However, since monoamines oxidize at similar potentials and can be released in the same brain region, FSCV lacks specificity for differentiating between dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine [114]. The development of fluorescent biosensors for neurotransmitter detection has overcome many of these limitations and provides exciting opportunities for visualizing neurotransmitter dynamics in specific cell types in behaving animals.

Perhaps the most well-studied fluorescent biosensors are the genetically encoded dopamine sensors, GPCR-activation-based-dopamine (GRABDA) [71] and dLight [72]. These sensors detect in vivo dopamine release with subsecond resolution, submicromolar affinity, and high molecular specificity. Fiber photometry is a powerful tool for in vivo imaging of biosensors, as they can be targeted to specific cell types, and single-cell resolution is typically not required [71, 72]. In proof-of-concept studies, these sensors were used to detect dopamine release in response to natural and drug rewards [71, 72]. Sexual behavior and water delivery in water-restricted mice induced an increase in GRABDA fluorescence, whereas systemic administration of methylphenidate, a psychostimulant and norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor, caused a prolonged increase in dopamine release in the dorsal striatum [71]. Similarly, sucrose reward consumption induced an increase in dLight and jRGECO1a fluorescence in NAc neurons. On the other hand, footshocks suppressed dLight fluorescence while enhancing jRGECO1a fluorescence, indicating a dissociation between dopamine release and local circuit activity [72]. In addition, cocaine, but neither the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram nor the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine, increased the intensity of dLight fluorescence in the NAc [115]. These studies validate GRABDA and dLight as powerful tools for detecting dopamine release that occurs in response to natural and drug rewards in freely behaving animals.

Several studies have taken advantage of these tools to study how opioids and alcohol affect dopamine dynamics in rodents. Heroin administration increased GCaMP6m fluorescence in VTA dopamine neurons and dLight fluorescence in the NAc [116]. Consistent with this, heroin increased the number of c-Fos-expressing dopamine neurons in the VTA and occluded the optogenetic self-inhibition of VTA GABA neurons. These results support the idea that heroin increases dopamine release through disinhibition of VTA dopamine neurons. Dopamine biosensors were also used to study how different patterns of drug exposure can produce differing effects on behavior [115]. Morphine was given in intermittent doses that resulted in short periods of withdrawal; compared to a continuous infusion, intermittent dosing led to increased amplitude of spontaneous dLight transients in the NAc and locomotor sensitization, despite similar levels of serum morphine after a week under both protocols. In addition, intermittent dosing exacerbated morphine-evoked transcriptional adaptations in the NAc and dorsal striatum, perhaps as a consequence of altered dopamine dynamics. dLight was also used to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of dopamine release in various phases of alcohol self-administration [117]. Patterns of correlated VTA Ca2+ and NAc dLight fluorescence emerged over the course of self-administration training, which vanished during extinction and reappeared during relapse. Further analysis suggested that differential activity patterns in subregional VTA-NAc projections were involved in context-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking and reacquisition of alcohol consumption, which are related but distinct models of relapse. Extinction training did not return the mesolimbic circuits to a naive state, which may help explain why extinction training is not typically an effective treatment for alcohol dependence. Continued innovation in biosensors and new technological developments in fiber photometry, such as wireless fiber photometry [118] and multi-site recording using high density fiber arrays [119], will provide further flexibility for experimental design and expand our understanding of how cell activity in relevant neural circuits contributes to behavioral dysfunction in addiction models.

Conclusion

Enormous strides have been made in developing novel tools for manipulating and observing neural activity in behaving animals. Application of these tools has led to a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying reward processing and drug addiction. Optogenetics enables dissection of functional neural circuits involved in addiction and characterization of drug-induced cellular and synaptic adaptations. Meanwhile, miniscopes and fiber photometry provide real-time monitoring of cell-type- and pathway-specific neuronal activity in vivo. Further, optogenetics can be combined with miniscope or fiber photometry, allowing for simultaneous manipulation and observation of neural activity [104]. Looking forward, the continued development of wireless miniscope [120–122] and fiber photometry [118] technology will likely facilitate and improve behavioral studies, as animals would no longer be tethered, minimizing behavioral interference. This will be particularly beneficial in the setting of self-administration experiments where additional cables can interfere with intravenous infusion tubing. Also mentioned earlier, the compact NINscope enables observation of two separate brain regions in one mouse [101], while multi-fiber arrays for fiber photometry can record up to 48 regions at once [119]. To our knowledge, wireless technologies, NINscope, and multi-fiber arrays have yet to be utilized in addiction research. There remains immense untapped potential for implementing these exciting technologies to advance research into the neurobiology of drug addiction.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants F30-MH115536 (to C.R.V.), F31-DA054759 (to V.F.), R01-DA047269, R01-DA035217 and R01-MH121454 (to Q.-S.L.). It was also partially funded through the Research and Education Initiative Fund, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin. C.R.V. and S.T.S. are members of the Medical Scientist Training Program at MCW, which is partially supported by a training grant from NIGMS T32-GM080202.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Earp BD, Skorburg JA, Everett JAC, Savulescu J. Addiction, identity, morality. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2019;10:136–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rise J, Halkjelsvik T. Conceptualizations of addiction and moral responsibility. Front Psychol 2019;10:1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutt DJ, Lingford-Hughes A, Erritzoe D, Stokes PR. The dopamine theory of addiction: 40 years of highs and lows. Nature reviews 2015;16:305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:760–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lüscher C The emergence of a circuit model for addiction. Annual review of neuroscience 2016;39:257–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li MD, Burmeister M. New insights into the genetics of addiction. Nature reviews Genetics 2009;10:225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducci F, Goldman D. The genetic basis of addictive disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2012;35:495–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhl GR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Li CY, Contoreggi C, Hess J, et al. Molecular genetics of addiction and related heritable phenotypes: genome-wide association approaches identify “connectivity constellation” and drug target genes with pleiotropic effects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2008;1141:318–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olds J Self-stimulation of the brain; its use to study local effects of hunger, sex, and drugs. Science (New York, NY 1958;127:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olds J, Milner P. Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1954;47:419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mark VH, Chato JC, Eastman FG, Aronow S, Ervin FR. Localized cooling in the brain. Science (New York, NY 1961;134:1520–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poirier LJ, Singh P, Boucher R, Bouvier G, Olivier A, Larochelle P. Effect of brain lesions on striatal monoamines in the cat. Archives of Neurology 1967;17:601–08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khavari KA. Chemical microinjections into brain of free-moving small laboratory animals. Physiology & behavior 1970;5:1187–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatakis AM, Stuber GD. Optogenetic strategies to dissect the neural circuits that underlie reward and addiction. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2012;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong Y, Taylor JR, Wolf ME, Shaham Y. Circuit and Synaptic Plasticity Mechanisms of Drug Relapse. J Neurosci 2017;37:10867–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunders BT, Richard JM, Janak PH. Contemporary approaches to neural circuit manipulation and mapping: focus on reward and addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015;370:20140210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Namboodiri VMK, Basiri ML, Stamatakis AM, Stuber GD. Developments from bulk optogenetics to single-cell strategies to dissect the neural circuits that underlie aberrant motivational states. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Siciliano CA, Tye KM. Leveraging calcium imaging to illuminate circuit dysfunction in addiction. Alcohol 2019;74:47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, DeMarco EM, Witzel LS, Keighron JD. A selected review of recent advances in the study of neuronal circuits using fiber photometry. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior 2021;201:173113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leopold AV, Shcherbakova DM, Verkhusha VV. Fluorescent biosensors for neurotransmission and neuromodulation: engineering and applications. Front Cell Neurosci 2019;13:474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabatini BL, Tian L. Imaging neurotransmitter and neuromodulator dynamics in vivo with genetically encoded indicators. Neuron 2020;108:17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner CT, Williams CJ, Fermelia MR, Lin DT, Li Y. Circuit mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases: a new frontier with miniature fluorescence microscopy. Frontiers in neuroscience 2019;13:1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci 2005;8:1263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Gutierrez DV, Hanson MG, Han J, Mark MD, Chiel H, et al. Fast noninvasive activation and inhibition of neural and network activity by vertebrate rhodopsin and green algae channelrhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005;102:17816–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagel G, Brauner M, Liewald JF, Adeishvili N, Bamberg E, Gottschalk A. Light activation of channelrhodopsin-2 in excitable cells of Caenorhabditis elegans triggers rapid behavioral responses. Current biology : CB 2005;15:2279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Davidson TJ, Mogri M, Deisseroth K. Optogenetics in neural systems. Neuron 2011;71:9–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deisseroth K, Hegemann P. The form and function of channelrhodopsin. Science (New York, NY 2017;357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Petreanu L, Huber D, Sobczyk A, Svoboda K. Channelrhodopsin-2-assisted circuit mapping of long-range callosal projections. Nat Neurosci 2007;10:663–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuber GD. Dissecting the neural circuitry of addiction and psychiatric disease with optogenetics. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;35:341–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kupchik YM, Brown RM, Heinsbroek JA, Lobo MK, Schwartz DJ, Kalivas PW. Coding the direct/indirect pathways by D1 and D2 receptors is not valid for accumbens projections. Nat Neurosci 2015;18:1230–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annual review of neuroscience 2011;34:441–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang H, de Jong JW, Tak Y, Peck J, Bateup HS, Lammel S. Nucleus accumbens subnuclei regulate motivated behavior via direct inhibition and disinhibition of vta dopamine subpopulations. Neuron 2018;97:434–49 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bocklisch C, Pascoli V, Wong JC, House DR, Yvon C, de Roo M, et al. Cocaine disinhibits dopamine neurons by potentiation of GABA transmission in the ventral tegmental area. Science (New York, NY 2013;341:1521–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales M, Margolis EB. Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour. Nature reviews 2017;18:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi J, Zhang S, Wang HL, Barker DJ, Miranda-Barrientos J, Morales M. VTA glutamatergic inputs to nucleus accumbens drive aversion by acting on GABAergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci 2016;19:725–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo JH, Zell V, Gutierrez-Reed N, Wu J, Ressler R, Shenasa MA, et al. Ventral tegmental area glutamate neurons co-release GABA and promote positive reinforcement. Nature communications 2016;7:13697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zell V, Steinkellner T, Hollon NG, Warlow SM, Souter E, Faget L, et al. VTA glutamate neuron activity drives positive reinforcement absent dopamine co-release. Neuron 2020;107:864–73 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scofield MD, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Spencer S, Smith ACW, et al. The nucleus accumbens: mechanisms of addiction across drug classes reflect the importance of glutamate homeostasis. Pharmacological reviews 2016;68:816–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf ME. Synaptic mechanisms underlying persistent cocaine craving. Nature reviews 2016;17:351–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conrad KL, Tseng KY, Uejima JL, Reimers JM, Heng LJ, Shaham Y, et al. Formation of accumbens GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors mediates incubation of cocaine craving. Nature 2008;454:118–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee BR, Ma YY, Huang YH, Wang X, Otaka M, Ishikawa M, et al. Maturation of silent synapses in amygdala-accumbens projection contributes to incubation of cocaine craving. Nat Neurosci 2013;16:1644–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma YY, Lee BR, Wang X, Guo C, Liu L, Cui R, et al. Bidirectional modulation of incubation of cocaine craving by silent synapse-based remodeling of prefrontal cortex to accumbens projections. Neuron 2014;83:1453–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Backman CM, Malik N, Zhang Y, Shan L, Grinberg A, Hoffer BJ, et al. Characterization of a mouse strain expressing Cre recombinase from the 3’ untranslated region of the dopamine transporter locus. Genesis 2006;44:383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schultz W Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol 1998;80:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai HC, Zhang F, Adamantidis A, Stuber GD, Bonci A, de Lecea L, et al. Phasic firing in dopaminergic neurons is sufficient for behavioral conditioning. Science (New York, NY 2009;324:1080–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordan CJ, Humburg B, Rice M, Bi GH, You ZB, Shaik AB, et al. The highly selective dopamine D(3)R antagonist, R-VK4–40 attenuates oxycodone reward and augments analgesia in rodents. Neuropharmacology 2019;158:107597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galaj E, Han X, Shen H, Jordan CJ, He Y, Humburg B, et al. Dissecting the role of GABA neurons in the VTA versus SNr in opioid reward. J Neurosci 2020;40:8853–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pascoli V, Terrier J, Hiver A, Luscher C. Sufficiency of mesolimbic dopamine neuron stimulation for the progression to addiction. Neuron 2015;88:1054–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown MT, Bellone C, Mameli M, Labouebe G, Bocklisch C, Balland B, et al. Drug-driven AMPA receptor redistribution mimicked by selective dopamine neuron stimulation. PloS one 2010;5:e15870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Y, Wienecke CF, Nachtrab G, Chen X. A thalamic input to the nucleus accumbens mediates opiate dependence. Nature 2016;530:219–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wise RA, Rompre PP. Brain dopamine and reward. Annual review of psychology 1989;40:191–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis TC, Yano H, Demarest TG, Shen H, Bonci A. High-frequency activation of nucleus accumbens d1-msns drives excitatory potentiation on D2-MSNs. Neuron 2019;103:432–44 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lobo MK, Covington HE 3rd, Chaudhury D, Friedman AK, Sun H, Damez-Werno D, et al. Cell type-specific loss of BDNF signaling mimics optogenetic control of cocaine reward. Science (New York, NY 2010;330:385–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kravitz AV, Tye LD, Kreitzer AC. Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement. Nat Neurosci 2012;15:816–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soares-Cunha C, de Vasconcelos NAP, Coimbra B, Domingues AV, Silva JM, Loureiro-Campos E, et al. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons subtypes signal both reward and aversion (vol 25, pg 3241, 2020). Molecular psychiatry 2020;25:3448–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolff SB, Olveczky BP. The promise and perils of causal circuit manipulations. Current opinion in neurobiology 2018;49:84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kravitz AV, Bonci A. Optogenetics, physiology, and emotions. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 2013;7:169–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stefanik MT, Moussawi K, Kupchik YM, Smith KC, Miller RL, Huff ML, et al. Optogenetic inhibition of cocaine seeking in rats. Addiction biology 2013;18:50–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arguello AA, Richardson BD, Hall JL, Wang R, Hodges MA, Mitchell MP, et al. Role of a lateral orbital frontal cortex-basolateral amygdala circuit in cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017;42:727–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pascoli V, Turiault M, Luscher C. Reversal of cocaine-evoked synaptic potentiation resets drug-induced adaptive behaviour. Nature 2011;481:71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pascoli V, Terrier J, Espallergues J, Valjent E, O’Connor EC, Luscher C. Contrasting forms of cocaine-evoked plasticity control components of relapse. Nature 2014;509:459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schall TA, Wright WJ, Dong Y. Nucleus accumbens fast-spiking interneurons in motivational and addictive behaviors. Molecular psychiatry 2021;26:234–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu J, Yan Y, Li KL, Wang Y, Huang YH, Urban NN, et al. Nucleus accumbens feedforward inhibition circuit promotes cocaine self-administration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E8750–e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 2013;499:295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Piatkevich KD, Bensussen S, Tseng HA, Shroff SN, Lopez-Huerta VG, Park D, et al. Population imaging of neural activity in awake behaving mice. Nature 2019;574:413–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang W, Kim CK, Ting AY. Molecular tools for imaging and recording neuronal activity. Nature chemical biology 2019;15:101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seidemann E, Chen Y, Bai Y, Chen SC, Mehta P, Kajs BL, et al. Calcium imaging with genetically encoded indicators in behaving primates. Elife 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dimidschstein J, Chen Q, Tremblay R, Rogers SL, Saldi GA, Guo L, et al. A viral strategy for targeting and manipulating interneurons across vertebrate species. Nat Neurosci 2016;19:1743–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li SJ, Vaughan A, Sturgill JF, Kepecs A. A viral receptor complementation strategy to overcome cav-2 tropism for efficient retrograde targeting of neurons. Neuron 2018;98:905–17.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tervo DG, Hwang BY, Viswanathan S, Gaj T, Lavzin M, Ritola KD, et al. A designer AAV variant permits efficient retrograde access to projection neurons. Neuron 2016;92:372–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun F, Zeng J, Jing M, Zhou J, Feng J, Owen SF, et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor enables rapid and specific detection of dopamine in flies, fish, and mice. Cell 2018;174:481–96.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patriarchi T, Cho JR, Merten K, Howe MW, Marley A, Xiong WH, et al. Ultrafast neuronal imaging of dopamine dynamics with designed genetically encoded sensors. Science (New York, NY 2018;360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Feng J, Zhang C, Lischinsky JE, Jing M, Zhou J, Wang H, et al. A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor for rapid and specific in vivo detection of norepinephrine. Neuron 2019;102:745–61.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jing M, Li Y, Zeng J, Huang P, Skirzewski M, Kljakic O, et al. An optimized acetylcholine sensor for monitoring in vivo cholinergic activity. Nature methods 2020;17:1139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dong A, He K, Dudok B, Farrell J, Guan W, Liput D, et al. A fluorescent sensor for spatiotemporally resolved endocannabinoid dynamics in vitro and in vivo. bioRxiv; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Banion CP, Yasuda R. Fluorescent sensors for neuronal signaling. Current opinion in neurobiology 2020;63:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Girven KS, Sparta DR. Probing deep brain circuitry: new advances in in vivo calcium measurement strategies. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017;8:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ghosh KK, Burns LD, Cocker ED, Nimmerjahn A, Ziv Y, Gamal AE, et al. Miniaturized integration of a fluorescence microscope. Nature methods 2011;8:871–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Glas A, Hübener M, Bonhoeffer T, Goltstein PM. Benchmarking miniaturized microscopy against two-photon calcium imaging using single-cell orientation tuning in mouse visual cortex. PloS one 2019;14:e0214954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ziv Y, Ghosh KK. Miniature microscopes for large-scale imaging of neuronal activity in freely behaving rodents. Current opinion in neurobiology 2015;32:141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Resendez SL, Stuber GD. In vivo calcium imaging to illuminate neurocircuit activity dynamics underlying naturalistic behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015;40:238–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heinsbroek JA, Bobadilla AC, Dereschewitz E, Assali A, Chalhoub RM, Cowan CW, et al. Opposing regulation of cocaine seeking by glutamate and gaba neurons in the ventral pallidum. Cell reports 2020;30:2018–27.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J Neurosci 2008;28:6046–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cameron CM, Murugan M, Choi JY, Engel EA, Witten IB. Increased Cocaine Motivation Is Associated with Degraded Spatial and Temporal Representations in IL-NAc Neurons. Neuron 2019;103:80–91.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Semon RW. The Mneme George Allen & Unwin: London; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Josselyn SA, Kohler S, Frankland PW. Finding the engram. Nature reviews 2015;16:521–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hebb DO. The organization of behavior: a neuropsychological theory Wiley. 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wong-Riley MT. Cytochrome oxidase: an endogenous metabolic marker for neuronal activity. Trends in neurosciences 1989;12:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sheng M, Greenberg ME. The regulation and function of c-fos and other immediate early genes in the nervous system. Neuron 1990;4:477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.DeNardo L, Luo L. Genetic strategies to access activated neurons. Current opinion in neurobiology 2017;45:121–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Whitaker LR, Hope BT. Chasing the addicted engram: identifying functional alterations in Fos-expressing neuronal ensembles that mediate drug-related learned behavior. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, NY) 2018;25:455–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barbera G, Liang B, Zhang L, Gerfen Charles R, Culurciello E, Chen R, et al. Spatially compact neural clusters in the dorsal striatum encode locomotion relevant information. Neuron 2016;92:202–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xia L, Nygard SK, Sobczak GG, Hourguettes NJ, Bruchas MR. Dorsal-CA1 hippocampal neuronal ensembles encode nicotine-reward contextual associations. Cell reports 2017;19:2143–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eichenbaum H, Dudchenko P, Wood E, Shapiro M, Tanila H. The Hippocampus, Memory, and Place Cells: Is It Spatial Memory or a Memory Space? Neuron 1999;23:209–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Siciliano CA, Noamany H, Chang CJ, Brown AR, Chen X, Leible D, et al. A cortical-brainstem circuit predicts and governs compulsive alcohol drinking. Science (New York, NY 2019;366:1008–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rubin A, Sheintuch L, Brande-Eilat N, Pinchasof O, Rechavi Y, Geva N, et al. Revealing neural correlates of behavior without behavioral measurements. Nature communications 2019;10:4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lecca S, Namboodiri VMK, Restivo L, Gervasi N, Pillolla G, Stuber GD, et al. Heterogeneous Habenular Neuronal Ensembles during Selection of Defensive Behaviors. Cell reports 2020;31:107752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aharoni D, Hoogland TM. Circuit investigations with open-source miniaturized microscopes: past, present and future. Front Cell Neurosci 2019;13:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Resendez SL, Jennings JH, Ung RL, Namboodiri VMK, Zhou ZC, Otis JM, et al. Visualization of cortical, subcortical and deep brain neural circuit dynamics during naturalistic mammalian behavior with head-mounted microscopes and chronically implanted lenses. Nature protocols 2016;11:566–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gulati S, Cao VY, Otte S. Multi-layer Cortical Ca2+ Imaging in Freely Moving Mice with Prism Probes and Miniaturized Fluorescence Microscopy. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.de Groot A, van den Boom BJG, van Genderen RM, Coppens J, van Veldhuijzen J, Bos J, et al. NINscope, a versatile miniscope for multi-region circuit investigations. eLife 2020;9:e49987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kingsbury L, Huang S, Wang J, Gu K, Golshani P, Wu YE, et al. Correlated Neural Activity and Encoding of Behavior across Brains of Socially Interacting Animals. Cell 2019;178:429–46.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ozbay BN, Futia GL, Ma M, Bright VM, Gopinath JT, Hughes EG, et al. Three dimensional two-photon brain imaging in freely moving mice using a miniature fiber coupled microscope with active axial-scanning. Scientific Reports 2018;8:8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stamatakis AM, Schachter MJ, Gulati S, Zitelli KT, Malanowski S, Tajik A, et al. Simultaneous optogenetics and cellular resolution calcium imaging during active behavior using a miniaturized microscope. Frontiers in neuroscience 2018;12:496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wei C, Han X, Weng D, Feng Q, Qi X, Li J, et al. Response dynamics of midbrain dopamine neurons and serotonin neurons to heroin, nicotine, cocaine, and MDMA. Cell Discov 2018;4:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Calipari ES, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, Davidson TJ, Yorgason JT, Pena CJ, et al. In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:2726–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pascoli V, Hiver A, Van Zessen R, Loureiro M, Achargui R, Harada M, et al. Stochastic synaptic plasticity underlying compulsion in a model of addiction. Nature 2018;564:366–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Saunders BT, Richard JM, Margolis EB, Janak PH. Dopamine neurons create Pavlovian conditioned stimuli with circuit-defined motivational properties. Nat Neurosci 2018;21:1072–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Saunders A, Sabatini BL. Cre activated and inactivated recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors for neuronal anatomical tracing or activity manipulation. Current protocols in neuroscience 2015;72:1 24 1–1 24 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Meng C, Zhou J, Papaneri A, Peddada T, Xu K, Cui G. Spectrally resolved fiber photometry for multi-component analysis of brain circuits. Neuron 2018;98:707–17 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cui G, Jun SB, Jin X, Pham MD, Vogel SS, Lovinger DM, et al. Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature 2013;494:238–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Darvesh AS, Carroll RT, Geldenhuys WJ, Gudelsky GA, Klein J, Meshul CK, et al. In vivo brain microdialysis: advances in neuropsychopharmacology and drug discovery. Expert opinion on drug discovery 2011;6:109–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rodeberg NT, Sandberg SG, Johnson JA, Phillips PE, Wightman RM. Hitchhiker’s guide to voltammetry: acute and chronic electrodes for in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017;8:221–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ou Y, Buchanan AM, Witt CE, Hashemi P. Frontiers in electrochemical sensors for neurotransmitter detection: towards measuring neurotransmitters as chemical diagnostics for brain disorders. Analytical methods : advancing methods and applications 2019;11:2738–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lefevre EM, Pisansky MT, Toddes C, Baruffaldi F, Pravetoni M, Tian L, et al. Interruption of continuous opioid exposure exacerbates drug-evoked adaptations in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45:1781–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Corre J, van Zessen R, Loureiro M, Patriarchi T, Tian L, Pascoli V, et al. Dopamine neurons projecting to medial shell of the nucleus accumbens drive heroin reinforcement. Elife 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu Y, Jean-Richard-Dit-Bressel P, Yau JO, Willing A, Prasad AA, Power JM, et al. The Mesolimbic Dopamine Activity Signatures of Relapse to Alcohol-Seeking. J Neurosci 2020;40:6409–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burton A, Obaid SN, Vazquez-Guardado A, Schmit MB, Stuart T, Cai L, et al. Wireless, battery-free subdermally implantable photometry systems for chronic recording of neural dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:2835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sych Y, Chernysheva M, Sumanovski LT, Helmchen F. High-density multi-fiber photometry for studying large-scale brain circuit dynamics. Nature methods 2019;16:553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liberti WA, Perkins LN, Leman DP, Gardner TJ. An open source, wireless capable miniature microscope system. Journal of neural engineering 2017;14:045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shuman T, Aharoni D, Cai DJ, Lee CR, Chavlis S, Page-Harley L, et al. Breakdown of spatial coding and interneuron synchronization in epileptic mice. Nat Neurosci 2020;23:229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Barbera G, Liang B, Zhang L, Li Y, Lin DT. A wireless miniScope for deep brain imaging in freely moving mice. Journal of neuroscience methods 2019;323:56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]