Abstract

The contribution of acetate- and H2/CO2-dependent methanogenesis to total CH4 production was determined in excised washed rice roots by radiolabeling, methyl fluoride inhibition, and stable carbon isotope fractionation. Addition of ≥20 mM phosphate inhibited methanogenesis, which then was exclusively from H2/CO2. Otherwise, acetate contributed about 50 to 60% of the total methanogenesis, demonstrating that phosphate specifically inhibited acetotrophic methanogens on rice roots.

The trend toward increasing CH4 levels in our atmosphere (5, 13) and the contribution of CH4 to global warming (17) have raised interest in the microbial processes that contribute to the global CH4 cycle. Flooded rice fields are an important source of atmospheric CH4, contributing about 20% of the total CH4 budget (9, 17). Most (about 90%) of the CH4 emitted from rice fields is ventilated through rice plants (26). Recently, it was shown that CH4 is produced not only in anoxic rice field soil but also directly on the roots of rice plants, which are inhabited by a methanogenic flora that is distinct from that in rice field soil (14, 15, 16, 21). The relative contribution of the methanogens on rice roots versus those in the soil to the total emission of CH4 from rice fields is unknown. However, the microbial root flora possibly contributes a significant portion, since up to 50% of the CH4 that is emitted from rice fields originates from plant photosynthates that are excreted from rice roots (23) and about 3 to 6% of the photosynthetically fixed CO2 is converted to CH4 and emitted (10).

Recently, we have shown that excised washed rice roots that are incubated under anoxic conditions convert CO2 to acetate, propionate, and CH4 (7). The produced acetate, on the other hand, was usually not further converted to CH4, although Methanosarcina-like sequences of small-subunit rRNA genes were detected in the root preparations and low numbers of acetotrophic methanogens were found by most-probable-number cultivation (21). Methanosaeta-like methanogens, on the other hand, have so far only been observed in paddy soil, but not on rice roots (15, 16). CH4 production accelerated only occasionally, especially upon prolonged incubation or during incubation of roots without buffer, and only during these rare events did acetate-dependent methanogenesis operate (21).

We therefore hypothesized that the failure to detect acetotrophic methanogenesis in rice root preparations may be due to the specific incubation conditions used. Acetotrophic methanogens are, indeed, sensitive to incubation conditions. For example, acetate-dependent methanogenesis in anoxic paddy soil is inactivated when the soil slurry is stirred with a magnetic bar, which destroys Methanosarcina cells (11). Since inactivation by mechanical forces was unlikely for the root incubations, we considered the possibility that the phosphate buffer which was used as the incubation medium was inhibitory. Here, we report that this was, indeed, the case.

The growth of rice plants, the preparation of rice roots, and the incubation experiments have already been described in detail (7). Briefly, rice plants (Oryza sativa, var. Roma, type japonica) were grown in a greenhouse. After 12 to 14 weeks, the plants were removed from the soil and the roots were washed, cut with a razor blade, and kept under N2. Aliquots of fresh roots (5 or 10 g) were incubated at room temperature (about 25°C) in 50 ml of anoxic sterile buffer under an N2 atmosphere using stoppered glass bottles (150-ml volume). The buffer consisted either of demineralized water plus 5 g of marble granules (0.5- to 2.0-mm size, consisting of CaCO3; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or of phosphate buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, 17 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM MgCl2), pH 7.0. Gas samples (0.25 to 1.0 ml) and liquid samples (0.5 ml) were analyzed as previously described (7). In some experiments, CH3F was added to the gas phase at a concentration of 1.0%. Radiotracer experiments were done as previously described (7) by adding 50 to 100 μCi of NaH14CO3 or Na-[2-14C]acetate. The fraction (f) of CH4 that was produced by the reduction of H14CO3− was calculated from the specific radioactivities of 14CH4 (SRCH4) and 14CO2 (SRCO2) measured in the gas phase using the formula f = SRCH4/SRCO2. The fraction of acetate carbon that was produced by reduction of H14CO3− and the fraction of CH4 that was produced by cleavage of acetate were calculated analogously.

Stable-isotope analysis of 13C/12C in gas samples was performed using a gas chromatograph combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) system purchased from Finnigan (Thermoquest, Bremen, Germany). The operation principle was described previously (4, 30). The isotopes were detected in a Finnigan MAT delta plus IRMS apparatus. The CH4 and CO2 in the gas samples (10 to 400 μl) were separated in a Hewlett-Packard 6890 gas chromatograph operating with a Pora Plot Q column (27.5-m length, 0.32-mm inside diameter, 10-μm film thickness; Chrompack, Frankfurt, Germany) at 25°C and He (99.996% purity, 2.6 ml min−1) as the carrier gas. The separated gases were then converted to CO2 in a Finnigan Standard GC Combustion Interface III and transferred into the IRMS apparatus. The working standard was CO2 gas (99.998% purity; Messer-Griessheim, Düsseldorf, Germany) calibrated against Pee Dee Belemnite carbonate. The isotopic ratios were expressed as follows in the delta notation: δ13C = 103 (Rsa/Rst − 1) with R = 13C/12C of the sample (sa) and the standard (st), respectively. The precision of repeated analysis was ±0.2‰ when 1.3 nmol of CH4 was injected. The fractionation factor α for CH4 formation from CO2 was obtained from the formula α = (δ13CO2 + 103)/(δ13CH4 + 103) (35).

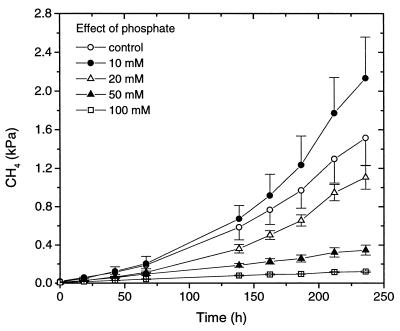

Both phosphate and marble granules buffered the root incubations sufficiently well to keep the pH within a physiological pH range of 6.6 to 7.1. When phosphate was added to marble-buffered root incubations, CH4 production was inhibited at phosphate concentrations of ≥20 mM (Fig. 1). Addition of only 10 mM phosphate, on the other hand, slightly enhanced the production of CH4.

FIG. 1.

Effect of phosphate addition on CH4 production by excised washed rice roots (10-g fresh weight) incubated in 50 ml of water with 5 g of marble granules (control). Different concentrations of phosphate were adjusted by addition of phosphate buffer. Each point is the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

The roots that were incubated in 50 mM phosphate buffer in the presence of NaH14CO3 produced 14CH4 for about 10 days. The final CH4 partial pressure was about 50 to 150 Pa. Methyl fluoride has been shown to preferentially inhibit acetotrophic methanogenesis (8, 14, 18). However, addition of methyl fluoride inhibited neither the production of CH4 nor the production of 14CH4 from NaH14CO3, indicating that all of the CH4 produced originated from CO2 reduction. CO2 was not limiting, as it increased to partial pressures of >2 kPa within 50 h. These observations corroborated results of earlier experiments which were also conducted with 50 mM phosphate buffer (7, 21).

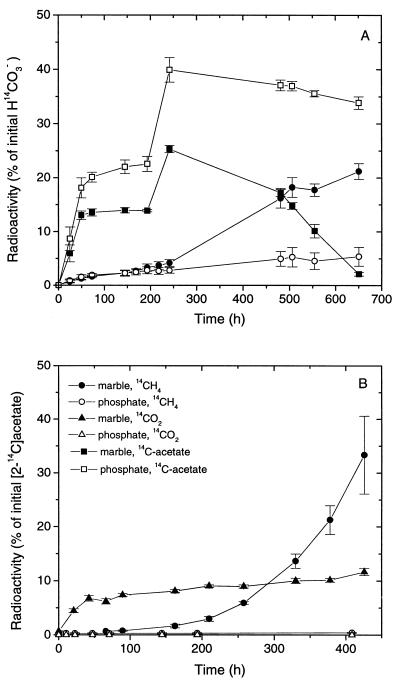

By contrast, root incubations buffered with marble granules produced much more CH4 (>5,000 Pa) during 10 days with gradually increasing rates. CO2 was produced to partial pressures (>2 kPa within 50 h) similar to those found in the phosphate-buffered incubations. Addition of methyl fluoride partially inhibited the production of total CH4 by about 50%, indicating that acetotrophic methanogenesis contributed substantially to CH4 production. Production of 14CH4 from NaH14CO3 was also enhanced in marble-buffered incubations compared to phosphate-buffered incubations (Fig. 2A). The percentage of CH4 produced from CO2, which was calculated from the specific radioactivities of 14CH4 and 14CO2, was much lower in the incubations with marble granules (63% ± 9%; mean ± standard deviation [SD]; n = 12) than in those with phosphate (102% ± 8%).

FIG. 2.

Production of 14CH4 and [14C]acetate from NaH14CO3 (A) and of 14CH4 and 14CO2 from [2-14C]acetate (B) by excised washed rice roots (10-g fresh weight) incubated in either 50 ml of phosphate buffer, pH 7, or 50 ml of water with 5 g of marble granules. Experiments A and B were done with different root preparations. Each point is the mean ± SD of triplicate determinations.

Acetate was produced simultaneously and accumulated to maximum concentrations of 10 to 13 mM both with marble granules and with phosphate. Labeling experiments with NaH14CO3 showed that CO2 was converted to acetate (Fig. 2A). As in earlier experiments (7), a relatively large percentage of the acetate carbon originated from CO2, both in the marble-buffered (46% ± 19%) and in the phosphate-buffered (57% ± 15%) incubations. However, the radioactive acetate was subsequently consumed in the marble-buffered incubations, presumably by conversion to CH4, whereas it stayed constant in the phosphate-buffered incubations (Fig. 2A). Total acetate also decreased from about 10 to 4 mM until the end of incubation.

Phosphate-buffered root incubations did not convert [2-14C]acetate (Fig. 2B), as found earlier (21). Marble-buffered root incubations, on the other hand, converted [2-14C]acetate to 14CH4 plus 14CO2 (Fig. 2B). 14CO2 was produced right in the beginning of the incubation but soon reached a constant level equivalent to about 8 to 10% of the initially added [2-14C]acetate. We assume that acetate was oxidized by iron-reducing bacteria during this phase, since the roots were partially encrusted with ferric iron plaques, which may have served as an oxidant. Conversion of [2-14C]acetate to 14CH4, on the other hand, gradually increased with time, as CH4 production did. The percentage of CH4 produced from acetate, which was calculated from the specific radioactivities of 14CH4 and [2-14C]acetate, was 58% ± 9%.

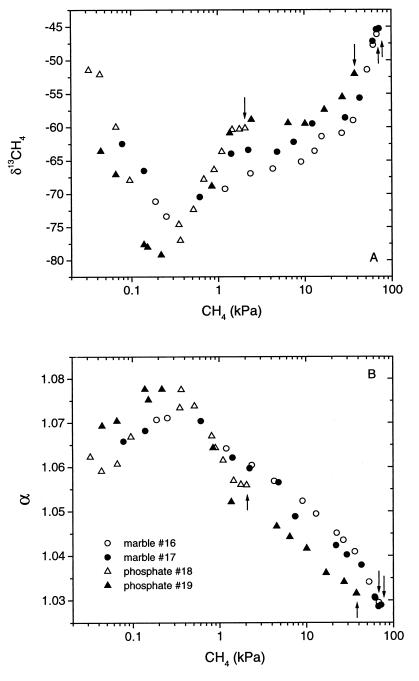

The increased contribution of acetate to total CH4 production in the absence of phosphate also affected the stable isotopic signature of the CH4 produced and the apparent fractionation factor (α) that is calculated from δ13CO2 and δ13CH4. The stable isotope signatures of CH4 and CO2 were measured in both marble- and phosphate-buffered root incubations. Production of CH4 was markedly increased in the marble-buffered incubations. However, one of the phosphate-buffered incubations (no. 19) eventually also exhibited accelerated CH4 production, as occasionally observed before (21). Two phases of CH4 production could be distinguished. During the initial phase, CH4 accumulated to partial pressures of about 0.2 to 0.5 kPa, the values of δ13CH4 decreased to about −80‰ (Fig. 3A), and α increased to >1.07 (Fig. 3B). Such a relatively high fractionation factor typically indicates a strong contribution of CO2-dependent methanogenesis to total CH4 production (1, 3, 31, 32, 35). During the second phase, CH4 accumulated further, δ13CH4 increased again and the fractionation factor decreased, indicating an increased contribution of acetotrophic methanogenesis to total CH4 production (Fig. 3). The extent to which α decreased (and δ13CH4 increased) was dependent on how much CH4 eventually accumulated, i.e., much lower values in the marble-buffered incubations than in the phosphate-buffered incubations.

FIG. 3.

Changes in δ13CH4 (A) and α (B) with increasing partial pressure of accumulating CH4. Each arrow indicates the final CH4 partial pressure that was reached in each individual incubation (no. 16 to 19).

In summary, these results demonstrate that phosphate at concentrations of ≥20 mM inhibited CH4 production on excised washed rice roots, in particular, by impeding acetotrophic methanogenesis. In phosphate-buffered incubations, only relatively small amounts of CH4 were produced by reduction of CO2. Simultaneously, large amounts of acetate (>10 mM) were produced, about half by reduction of CO2. However, the produced acetate was not further metabolized. In the absence of phosphate, on the other hand, the produced acetate was eventually further metabolized and CH4 production accelerated.

Molecular analysis has indicated that Methanosarcina species are responsible for the observed conversion of acetate to CH4 on rice roots (16, 21). Methanosarcina species are known to exhibit rather high Km and threshold values for acetate (19). This may be the reason why acetotrophic methanogenesis started not immediately at the beginning of incubation but only when sufficient acetate had accumulated. Radiolabeling studies have shown that acetate is an intermediate in the conversion of photosynthetically assimilated CO2 into CH4 (10). Acetate may be excreted from the rice roots or may be produced by fermentation of other substrates (e.g., sugars or polysaccharides) which may originate from either root exudates or root decay. Fermentative acetate production includes homoacetogenesis from H2-CO2 (7), probably by Sporomusa species that were shown to be members of the rice root microflora (24). The concentrations of acetate in the rhizosphere depend on the rice variety and exhibit pronounced spatial and seasonal variations in the range of micromolar to millimolar concentrations (25, 27), so that acetate is an important regulatory factor for CH4 production by the rice root microflora under in situ conditions.

Our results suggest that the phosphate concentration in the rhizosphere is another factor which possibly regulates acetate turnover and CH4 production on rice roots. Indeed, it has recently been shown that a low phosphate supply to rice plants results in enhancement of CH4 emission (22). This response may in part be due to the release of inhibition of acetotrophic methanogens on the roots. The mechanism by which increased phosphate concentrations inhibit methanogens, acetotrophic ones in particular, is unknown. However, there seems to be a widespread awareness that buffering of culture media with more than 30 mM phosphate may result in inhibition of microbial growth (34), although details and specific observations are rarely described (2, 6). On the other hand, media buffered with 20 to 50 mM phosphate have frequently been used for cultivation of Methanosarcina (20, 28). However, the methanogens in the rhizosphere may be more sensitive to phosphate since it will be limiting unless the soil is fertilized. Rice roots efficiently take up phosphate for plant nutrition. Phosphate is only sparingly soluble in the presence of calcium and iron, which are present in paddy soil. Iron phosphates form precipitates on roots of wetland plants (29). For phosphate mobilization, roots excrete phosphatases and dissolve calcium phosphates by acidification (32). Phosphate concentrations in the rhizosphere of various plants were found to be below 30 to 35 μM (12). Consequently, the methanogenic microflora on plant roots may have adapted to low-phosphate conditions and thus may be relatively sensitive to high phosphate concentrations.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avery G B, Jr, Martens C S. Controls on the stable carbon isotopic composition of biogenic methane produced in a tidal freshwater estuarine sediment. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1999;63:1075–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartscht K, Cypionka H, Overmann J. Evaluation of cell activity and of methods for the cultivation of bacteria from a natural lake community. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair N E, Boehme S E, Carter W D., Jr . The carbon isotope biogeochemistry of methane production in anoxic sediments. 1. Field observations. In: Oremland R S, editor. Biogeochemistry of global change. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 574–593. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brand W A. High precision isotope ratio monitoring techniques in mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:225–235. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199603)31:3<225::AID-JMS319>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cicerone R J, Oremland R S. Biogeochemical aspects of atmospheric methane. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1988;2:299–327. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrad R. Wege des Hexoseabbaus in phototrophen Bakterien. Ph.D. thesis. Göttingen, Germany: University of Göttingen; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad R, Klose M. Anaerobic conversion of carbon dioxide to methane, acetate and propionate on washed rice roots. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;30:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1999.tb00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conrad R, Klose M. How specific is the inhibition by methyl fluoride of acetoclastic methanogenesis in anoxic rice field soil? FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;30:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crutzen P J. The role of methane in atmospheric chemistry and climate. In: von Engelhardt W, Leonhardt-Marek S, Breves G, Giesecke D, editors. Ruminant physiology: digestion, metabolism, growth and reproduction. Stuttgart, Germany: Enke; 1995. pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dannenberg S, Conrad R. Effect of rice plants on methane production and rhizospheric metabolism in paddy soil. Biogeochemistry. 1999;45:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dannenberg S, Wudler J, Conrad R. Agitation of anoxic paddy soil slurries affects the performance of the methanogenic microbial community. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deweger L A, Dekkers L C, VanderBij A J, Lugtenberg B J J. Use of phosphate-reporter bacteria to study phosphate limitation in the rhizosphere and in bulk soil. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dlugokencky E J, Masarie K A, Lang P M, Tans P P. Continuing decline in the growth rate of the atmospheric methane burden. Nature. 1998;393:447–450. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frenzel P, Bosse U. Methyl fluoride, an inhibitor of methane oxidation and methane production. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;21:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Großkopf R, Janssen P H, Liesack W. Diversity and structure of the methanogenic community in anoxic rice paddy soil microcosms as examined by cultivation and direct 16S rRNA gene sequence retrieval. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:960–969. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.3.960-969.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Großkopf R, Stubner S, Liesack W. Novel euryarchaeotal lineages detected on rice roots and in the anoxic bulk soil of flooded rice microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4983–4989. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4983-4989.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change. The IPCC scientific assessment. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen P H, Frenzel P. Inhibition of methanogenesis by methyl fluoride: studies of pure and defined mixed cultures of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4552–4557. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4552-4557.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jetten M S M, Stams A J M, Zehnder A J B. Methanogenesis from acetate—a comparison of the acetate metabolism in Methanothrix soehngenii and Methanosarcina spp. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;88:181–197. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenealy W, Zeikus J G. Influence of corrinoid antagonists on methanogen metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:133–140. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.133-140.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehmann-Richter S, Großkopf R, Liesack W, Frenzel P, Conrad R. Methanogenic archaea and CO2-dependent methanogenesis on washed rice roots. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:159–166. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Y, Wassmann R, Neue H U, Huang C. Impact of phosphorus supply on root exudation, aerenchyma formation and methane emission of rice plants. Biogeochemistry. 1999;47:203–218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minoda T, Kimura M, Wada E. Photosynthates as dominant source of CH4 and CO2 in soil water and CH4 emitted to the atmosphere from paddy fields. J Geophys Res. 1996;101:21091–21097. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosencrantz D, Rainey F A, Janssen P H. Culturable populations of Sporomusa spp. and Desulfovibrio spp. in the anoxic bulk soil of flooded rice microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3526–3533. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3526-3533.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothfuss F, Conrad R. Vertical profiles of CH4 concentrations, dissolved substrates and processes involved in CH4 production in a flooded Italian rice field. Biogeochemistry. 1993;18:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schütz H, Seiler W, Conrad R. Processes involved in formation and emission of methane in rice paddies. Biogeochemistry. 1989;7:33–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigren L K, Byrd G T, Fisher F M, Sass R L. Comparison of soil acetate concentrations and methane production, transport, and emission in two rice cultivars. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1997;11:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith M R, Mah R A. Acetate as sole carbon and energy source for growth of Methanosarcina strain 227. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:993–999. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.5.993-999.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snowden R E D, Wheeler B D. Chemical changes in selected wetland plant species with increasing Fe supply, with specific reference to root precipitates and Fe tolerance. New Phytol. 1995;131:503–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1995.tb03087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugimoto A, Hong X, Wada E. Rapid and simple measurement of carbon isotope ratio of bubble methane using GC/C/IRMS. Mass Spectrosc. 1991;39:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugimoto A, Wada E. Carbon isotopic composition of bacterial methane in a soil incubation experiment: contributions of acetate and CO2/H2. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1993;57:4015–4027. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trolldenier G. Techniques for observing phosphorus mobilization in the rhizosphere. Biol Fertil Soils. 1992;14:121–125. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyler S C, Bilek R S, Sass R L, Fisher F M. Methane oxidation and pathways of production in a Texas paddy field deduced from measurements of flux, δ13C, and δD of CH4. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 1997;11:323–348. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veldkamp H. Enrichment cultures of prokaryotic organisms. Methods Microbiol. 1970;3A:305–361. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whiticar M J, Faber E, Schoell M. Biogenic methane formation in marine and freshwater environments: CO2 reduction vs. acetate fermentation—isotopic evidence. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1986;50:693–709. [Google Scholar]