Abstract

We examine the survey responses of 278 individuals who transitioned from the workplace to working from home (WFH) as a result of the Covid 19 pandemic to understand how individuals’ attainment of productivity in work and meaning in life are affected by WFH. We also assess their perceived stress and health challenges experienced since WFH. On average, workers perceive that productivity and meaning changed in opposite directions with the shift to WFH—productivity increased while the meaning derived from daily activities decreased. Stress was reduced while health problems increased. By investigating these changes, we identify important common sources of support and friction associated with remote work that affect multiple dimensions of work and life. For example, personal fortitude is an important source of support, and the intrusion of work into life is an important friction. Our findings lead to concrete recommendations for both organizational leaders and workers in setting key priorities for supporting remote work.

Keywords: Covid 19, Remote work, Working from home, Productivity, Wellbeing, Stress

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is believed to have originated in December of 2019. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of May 2021 there have been over 33 million confirmed cases and over a half of a million lives lost in the United States alone, with millions more lost around the world. As a means to manage the spread of COVID-19, the majority of American states and cities issued workplace restrictions (e.g., quarantine or “stay-at-home” orders). Although workplace restrictions have varied in start date, duration, and scope, under stay-at-home orders, employees not considered “essential” have shifted to remote work. Prior to the COVID-19 restrictions insight and practical recommendations concerning working from home (WFH) have largely focused on employees who work in positions that were deliberately planned to be WFH. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, was an unexpected event that was a huge shock to people’s lives and work on a global scale. The adjustments that individuals and organizations had to make were significant, fast, and memorable, and affected everyone within the same, very short period of time.

The dramatic, large-scale shift to WFH caused by the pandemic is an opportunity to learn about how WFH affects workers, both in terms of how they do their jobs and how it impacts their health and home life. Because the pandemic and the shift to WFH was an abrupt shock, organizations did not have time to plan and intervene with measures designed to smooth the transition for workers. This unfiltered unfolding of events lays bare the factors that influence productivity and wellbeing that may not be evident in connection with less extreme changes in the environment. Understanding the impact on workers and the factors involved can contribute to greater success for managers in supporting and retaining workers through a time of forced transition to WFH as has happened with the COVID-19 pandemic. Many workers and employers believe that WFH will continue on a large scale even when working remotely will not be necessary for health reasons. The lessons learned about WFH from the pandemic can also help shape approaches for implementing effective WFH policies and long-term remote assignments for strategic organizational reasons after the pandemic passes.

Our study examines questions that are important to employers and workers. Do workers perceive the transition to WFH as a negative or a positive experience, and what factors determine the difference? Do workers perceive WFH as less or more intense than the workplace, and on which dimensions? Does WFH entail a perception of reduced productivity or are workers freed to be more creative in their work? Do workers require a different style of supervision to thrive remotely? Are organizational values and communication important to the engagement of remote workers? Change can be a significant source of stress, which can have debilitating physical, emotional, and work-related outcomes. Not everyone responds to stress in the same way, with some better able to withstand stressors than others. What are the impacts of WFH for emotional and physical health? Are certain personality attributes amenable to remote work? Are there strategies that employers, workers, and co-workers can adopt that support emotional and physical health while working remotely?

Studying WFH is complicated because it involves both work and non-work aspects of life. Our study considers a wide variety of individual, environmental, and organizational factors that could influence an individual’s success in WFH. We find that the way the transition to WFH affected individuals across various elements of work and life is indeed complex. Changes in perceived productivity and creativity, meaning and interest in life, life stress, and health all changed significantly and yet in mixed directions. However, by investigating these changes, we identify important common sources of support and friction associated with remote work that affect multiple dimensions of work and life. Our findings lead to concrete recommendations for both organizational leaders and workers in setting key priorities for supporting remote work.

Our research on WFH

We collected data from an extensive survey that was designed to capture the breadth of workers’ experiences as work shifted from the workplace to the home. The survey was conducted online, in June–July 2020 using survey service Amazon Mechanical Turk. The final data set consisted of 278 U.S. workers who reported spending at least 50% of their time working at home or remotely rather than their usual workplace. A large majority of our respondents reported working from home 90–100% of the time. Participants provided responses to items on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 to 5 (e.g., Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree).

Participants varied in age, ranging from 22 to 74 years old. The average age was 39, and 45% of the sample identified as female. Education levels of the sample ranged from less than high school to the doctorate level. Most had a 4-year degree or more. The sample was 69% White, 13% Black or African American, 9% Asian, 8% Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish.

We also interviewed a convenience sample of eight individuals who transitioned to WFH to understand their experiences.

What we found

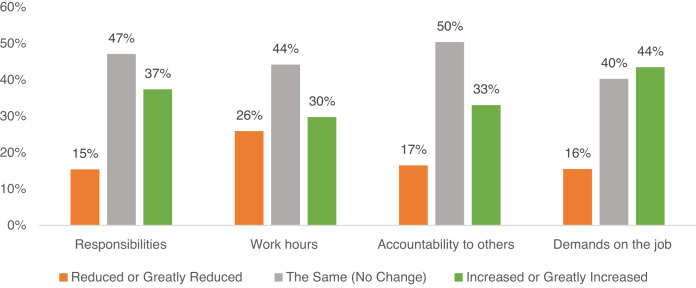

Job Changes, Transformation, and Continuing to Work from Home

We asked respondents how their jobs have changed since working remotely. In particular, respondents were asked how much change they experienced in their work responsibilities, hours, accountability to others, and demands on the job. As shown in Fig. 1 , nearly half of the respondents report that their responsibilities, working hours, accountability and demands have not changed, though roughly one-third said each of these measures of work intensity has increased. Demands on the job increased for 44% and, somewhat surprisingly given the transition to working from home, 33% said that accountability has increased.

Figure 1.

Job changes since working from home

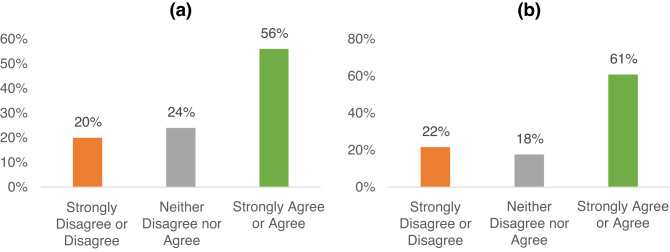

Remarkably, most respondents do not believe that the move to WFH was a disaster or even a regretful occurrence. On the contrary, as shown in Fig. 2 a and 2 b, 56% agree that the experience of working at home has been permanently transformative in a positive way, and 61% agreed that if they had a choice they would continue working remotely even when no longer necessary. These items are arguably the broadest possible questions one could pose concerning any experience—were you positively transformed, and do you wish to continue. Judging from these responses, the average perception of our respondents of the overall experience of WFH is clearly positive. This finding, especially the 61%, has significant implications for employers going forward. While it may be challenging to return individuals to the workplace, this finding suggests an opportunity for saving financial resources by employers substituting flexibility that workers value in place of financial incentives.

Figure 2.

a: Positive transformation. b: Continue remote

There is a great deal of variation in responses across individuals, however. Twenty percent of respondents disagree or strongly disagree that working from home is transformative in a positive way, and about the same percentage disagree or strongly disagree with wanting to continue working from home. This diversity of experiences and perceptions created by the unprecedented magnitude of changes in work and life associated with the pandemic is an ideal environment in which to study work and life and the factors that contributed to respondents’ positive or negative experiences.

Elements of wellbeing

We consider four indicators of wellbeing as the outcomes of interest. Productivity and creativity in work (Productivity) and a sense of meaning and interest in life (Meaning) are indicators of positive wellbeing. General stress in life (Perceived Stress) and Health Challenges are indicators of negative wellbeing. For these indicators, higher scores correspond to greater stress and poorer health. This section describes how these four indicators of wellbeing have been affected by the transition to WFH. The next section describes attributes of individuals and their workplaces that are potential sources of support or friction for WFH outcomes. The subsequent section reports the associations between the four indicators of wellbeing and potential sources of support or friction.

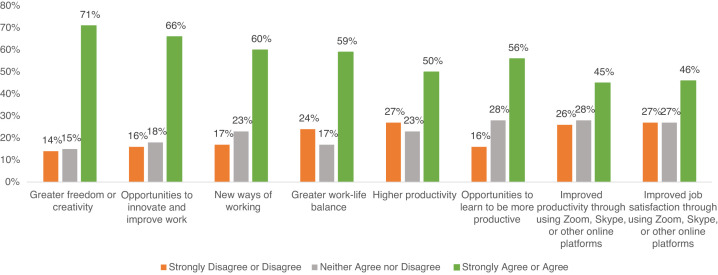

We created the composite Productivity measure by asking individuals whether their productivity or creativity in work had changed. Examples of such items are: “Adapting to a new work environment has given me more freedom or creativity in how I do my job”; and “I have used the new work environment as an opportunity to innovate and improve on how my work is done.” Fig. 3 presents the results for all six individual items whose average constitutes the index we label as Productivity. In addition, we asked two questions about the use of online platforms such as Zoom.

Figure 3.

Changes in productivity after working from home

As is evident in Fig. 3, over half of respondents endorse positive change in all aspects of productivity/creativity. Remarkably, over 70% of respondents say their new work environment has given them more freedom or creativity in how they do their job! Nearly half feel the use of online platforms has improved their job satisfaction or productivity. Yet, we also note that 27% disagree that their productivity has improved and 24% feel their work life balance has not improved.

An average of 3.0 for the composite Productivity index would indicate no change since WFH. The average from our survey responses is 3.57, which is significantly different from 3.0. On average, respondents perceive WFH as having a strong and positive impact on the aspects of work that the Productivity index captures. This is consistent with comments from our interviews. Below is a sample of comments from the interviews we conducted.

“I find myself reviewing emails on weekends if I have some down time at home to remain informed of office communication. Prior to WFH I did not review emails on weekends or after hours. WFH has heightened my awareness of work to remain updated on scheduled deadlines.”

“Working from home has improved my productivity, regardless of the fact that I'm now homeschooling as well. When working in the office I tend to get interrupted on a regular basis and it's impossible to take work home being a single mom with an eight-year-old. While working at home I'm able to create an environment in which we're both successful. I have less interruption and have learned to prioritize issues at hand more easily.”

“My productivity has improved somewhat. Whether I go into the office or WFH is determined much more by the type of work I expect that day rather than an obligation to be in the office. Having the flexibility makes work more enjoyable and increases my productivity and attitude.”

We created a measure that we label Change in Meaning by computing the differences in answers respondents gave to “before working from home” and “since working from home” versions of five items that assess the extent to which individuals derive meaning and interest from their lives. The average Meaning scores are 3.68 for “before” and 3.45 for “since.” The average Change in Meaning is −0.23, which is significantly less than 0 and indicates a clear reduction in meaning. Interestingly, the impact of WFH on productivity and meaning are mixed on average. On one hand, productivity and creativity in work is a beneficiary of WFH, and on the other, meaning and interest in life is a casualty of WFH.1

We measured overall levels of life stress using a 14-item scale that we refer to as Perceived Stress. Seven of the items are worded to measure perceptions of lesser stress, and seven are worded to measure perceptions of greater stress while WFH. Item examples are “Since working from home…I have felt that I was on top of things”, and “…I have felt difficulties were piling up so high that I could not overcome them.” Responses to the items that measure lesser stress were reversed in computing an average of the 14 items to create a composite Perceived Stress score.

A score below 3.0 corresponds to a reduction in Perceived Stress. The mean is 2.81, which is significantly different from 3.0, indicating less overall life stress being experienced since WFH. For almost all the individual items, a larger proportion of respondents report experiencing less stress since WFH than the proportion who experience more stress. The strongest response is agreement with “Since working from home I have been able to control the way I spend my time.” This response is mirrored in most of the other items. However, it is worth noting that a strong response was also reported in agreement with “Since working from home I found myself thinking about things that I have to accomplish.” Overall, however, the results for the Perceived Stress items suggest that respondents experience less stress and more control since working from home. These scores align with interview responses such as:

“I have the flexibility of working in my pajamas in the comfort of my home and my workday begins with very little stress.”

“WFH reduces commute time by 1.5 hours per day so I can “leave work” earlier and am not stressed from driving.”

“The ability to minimize extra steps in my day (i.e., commute, getting ready in the morning, etc.) has given me extra sleep hours and less stress to turn into better productivity.”

An interesting contrast exists between the responses to the Perceived Stress questions and those in Fig. 1. While somewhat more respondents report working longer hours than those who report working fewer (30% vs 26%), many more respondents feel in greater control of their time versus those who feel less in control (57% vs 17%). The simultaneous observations that respondents spend similar or more time working and yet feel much more in control of their time suggests that the way one spends time while working is an important aspect of the perceptions individuals have about the degree of control they have over their time in general. In other words, time spent working is not discounted as time that is out of one’s control.

This is good news for both workers and employers as it points to one of the reasons why WFH can benefit both productivity and control. Productivity and hours can increase without detrimental implications for workers if workers are allowed to control when the work is done. As noted in the interview comments above, WFH allows people greater flexibility, which they use to work more because other time-consuming aspects of going to work (e.g., commuting, getting ready, interruptions) are reduced.

We also measured changes in health challenges (or problems). Respondents were asked about their health pre and post WFH. The differences were averaged to create a measure we refer to as Increased Health Challenges. Scores above and below zero indicate increases and decreases in health challenges, respectively. The average Increased Health Challenges across respondents is 0.10 and is significantly greater than zero, indicating greater health challenges after WFH.

It is discouraging to note that the deterioration in health is not unique to a particular health issue. Five of the nine health challenges items have significantly higher mean scores post-WFH versus pre-WFH. The three largest differences correspond to the items: Poor appetite or overeating (difference 0.24), Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much (difference 0.24), and Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless (difference 0.19).

Taken together, these results indicate that, on average, the transition to WFH was associated with reductions in Perceived Stress and increases in Health Challenges. The impact of WFH on these elements of wellbeing was mixed on average, just as they were for Productivity and Meaning above. Although the measures of wellbeing are mixed in how their averages responded to the WFH transition in the pandemic, the analysis that follows shows there are important factors that are common to the changes in various aspects of wellbeing.

Potential sources of support and friction

We consider several potential sources of support and friction that might help explain the changes in elements of wellbeing as work moved to the home. For ease of exposition, we group the sources of support/friction into three types. The first type is connected to organizational or individual values. These are Organization Higher Purpose, Individual Values, and Work-Life Integration (WLI). The second type includes the interpersonal support of others within and outside the organization; and intra-personal support or personal fortitude. These measures are Leadership, Coworker Support, Social Support; and Core Self-Evaluation. Individuals’ values, the values of their organizations, the support they receive from leaders, co-workers, friends and family, and their perceptions of self-support are all potential resources that individuals can draw upon to help in maintaining productivity and meaning, and managing stress and health, through the experience of WFH.

The third type of support/friction reflects job attributes. The Job Security measure is based on respondents’ agreement or disagreement with adjectives that describe the security of their jobs. Remote Job Changes is an index constructed as the average of the scores on the work intensity questions whose responses are reported in Fig. 1.

We first present the averages for the support and friction sources overall, then we report how they contribute to each of the wellbeing outcomes.

The averages of the Higher Purpose and Individual Values composites are 3.60 and 3.25, which are both significantly greater than the value reflecting no change (3.0). These findings indicate that generally, respondents believed their organizations were communicating a higher purpose and that it was helpful in maintaining their commitment to work. In general, they also reported that their own inner world and values changed in positive ways while WFH.

Six work-life integration questions were assessed as before and after WFH, and the index we label as WLI Increase is the average of the differences between the pre and post measures of the six items. The pre- and post-WFH averages are 2.85 and 3.45, respectively, and their difference of 0.60 is significantly different from zero. This average indicates a large and significant increase in the degree to which respondents’ lives became integrated with their work in the transition to WFH. Notably, the WLI Increase is significantly negatively correlated with the Positive Transformation item, suggesting that the elevated degree of integration of work into life is experienced as an unwelcome intrusion rather than a positive aspect of WFH.

Respondents indicate very robust support from leaders and coworkers, with average scores of 4.10 versus a neutral score of 3.0 for both Leadership and Coworker Support. The average score for Social Support is somewhat lower but is still high with a mean of 3.67. High levels of self-support are also reported—the average of the composite Core Self-Evaluation measure is 3.66. Most of the participants in our study experience robust support at work from leaders and coworkers, considerable support from friends and family, and they perceive abundant capabilities for self-support.

Somewhat surprisingly, given the employment losses during the pandemic, Job Security also was reported as high on average. The mean score of 3.63 indicates that respondents agreed much more often than disagreed that positive adjectives describe the certainty of their jobs. The Job Security scores may reflect that our respondents work could be moved home, unlike others who were furloughed or fired when businesses had to close. Remote Job Changes had a mean score of 3.24 indicating that work intensity increased with the shift of work to the home. Interestingly, Remote Job Changes is positively correlated with Positive Transformation, indicating that greater work intensity is reported by those who also report having been positively transformed by shifting to WFH. This suggests that greater intensity assignments might have been accepted or even invited by those who felt capable of handling them, perhaps because their stress levels decreased.

Relations between elements of wellbeing and sources of support and friction

Table 1 reports the results of analyzing the associations between each element of wellbeing and all the potential sources of support and friction. The rows in Table 1 correspond to different elements of well-being, and the columns correspond to potential sources of support and friction. The sources of support and friction that are listed in particular cells identify the associations that are statistically reliable.

Table 1.

Sources of support and friction when working from home

| Sources of support | Sources of friction | |

|---|---|---|

| Productivity | • Higher Purpose | • Loss of Coworker Support |

| • Individual Values | • Work-Life Integration Increase | |

| • Social Support | ||

| • Core Self-Evaluation | ||

| • Remote Job Change (increased intensity) | ||

| • Supervisor | ||

| Increased Meaning | • Core Self-Evaluation | • Loss of Coworker Support |

| • Remote Job Change (increased intensity) | • Work-Life Integration Increase | |

| Perceived Stress | • Individual Values | • Work-Life Integration Increase |

| • Core Self-Evaluation | • Loss of Coworker Support | |

| Increased Health Challenges | • Core Self-Evaluation | • Work-Life Integration Increase |

| • Loss of Coworker Support | ||

We also include four other aspects of WFH that could serve as sources of support or friction for our respondents. Supervisor indicates whether or not the respondent supervises others (49% of respondents report supervising others). Creative Work indicates whether the respondent classifies their work as creative rather than repetitive or other (40% classify their work as creative). Children indicates whether the respondent has minor children at home (52% report children under age 12 at home). Housemate indicates whether the respondent shares the household with another adult (75% report having a housemate). Including these indicators enables us to consider whether these aspects of WFH are associated with changes in wellbeing and to control for these aspects in assessing the impact of the other sources of support/friction that we consider.

The first row reports associations with Productivity. Of the 13 potential sources of support and friction, Productivity is significantly associated with eight of them. The Organization’s Higher Purpose and Individual Values, personal fortitude (Core Self-Evaluation) and Social Support are all positively associated with perceptions of productivity/creativity improvements, as is the increase in work intensity (Remote Job Changes).

Supervisors tended to report positive changes in productivity more than non-supervisors perhaps due to the increases in working hours that supervisors reported since WFH compared to non-supervisors. One supervisor we interviewed suggested that managing remote workers created new challenges for her as well as her direct reports such as using new technology and scheduling.

The association between Productivity with Coworker Support is significant and negative. This makes sense because the value supportive coworkers bring to productivity and creativity in work occurs through interpersonal interactions, which were diminished by the transition to WFH. The negative association reflects the value lost from frequent interaction with supportive coworkers that happens in the workplace. Productivity and creativity in work is hindered by having support from coworkers taken away or made more distant by WFH. For these reasons, we identify the loss of Coworker Support as a friction.

The relation between Productivity and WLI Increase is also negative. Those who reported greater integration between their work and non-work lives as a consequence of the transition to WFH experienced declines in Productivity, perhaps because such integration was forced upon them. This possibility was noted earlier and is a strongly recurring theme in the other rows of Table 1. To our surprise, Job Security, and whether there are minor children or a housemate at home were not related to changes in Productivity.

The second row in Table 1 examines associations with Changes in Meaning. Interestingly Remote Job Change is significant and positive, suggesting that greater meaning was associated with an increase in work intensity. The strongest associations relate to Core Self Evaluation, Coworker Support and WLI Difference. These relations have similar interpretations as with Productivity. Remarkably, the withdrawal of coworker support that occurred with the transition of work to the home is associated with a very significant decrease in perceptions of meaning and interest in life in general. Likewise, the negative relation with WLI Increase indicates that the intrusion of work into non-work life degraded the attainment of meaning and interest in life outside of work.

Some of the measures that are significantly associated with Productivity are not associated with Changes in Meaning. Perhaps surprisingly, these include the values-based measures of Organization Higher Purpose and Individual Values, Leadership, and general support from family and friends. However, strong associations with both Productivity and Meaning do exist with the loss of Coworker Support, strong Core Self Evaluation and work interfering with life (WLI Increase), suggesting that the withdrawal of coworker support and the intrusion of work into non-work aspects of life degraded the attainment of meaning and interest in life in general as work transitioned to the home.

The results in rows one and two identify several common elements associated with changes in productivity and meaning, and some in surprising ways. Greater work intensity feeds meaning as well as productivity, while the integration of work and life is actually experienced as an intrusion that is detrimental to both productivity and meaning.

The third row of Table 1 reports associations with Perceived Stress. Four measures of support/friction are significant. Having a positive Core Self-Evaluation and a high score for Individual Values are associated with a greater reduction in Perceived Stress as work moved to the home. The significant positive association between Perceived Stress and WLI Increase indicates that respondents experienced greater general levels of stress from work intruding on life in the shift to WFH. The association with Coworker Support is also significant and positive. Coworkers were made distant in the shift to WFH. When coworkers who are supportive are made distant, their support in non-work aspects of life is diminished as well, which contributes to stress. As in the earlier rows for productivity and meaning, these findings indicate that the intrusion of work into life and diminished contact with supportive coworkers are frictions to remote work that are associated with greater stress in life.

The fourth row in Table 1 analyzes changes in work and increases in health challenges. Increases in WLI is positively related to Increased Health Challenges and the relation is highly significant. This indicates that the intrusion of work into life is an impairment to health. Despite the wide variety of non-work variables in the analysis, WLI, which bridges the work and non-work domains, has the largest and most significant relation with increased health challenges (e.g., eating and sleeping problems). The results in Table 1 indicate clearly that the loss of coworker support and the intrusion of work into life can make the difference between a positive or negative experience of WFH across a broad spectrum of wellbeing measures.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the overall experience of transitioning to WFH was positive in how individuals felt transformed by the experience and in their willingness to continue WFH even when it is no longer necessary. However, WFH varied in how it was experienced by workers across aspects of wellbeing. We identify a number of sources of support and friction that help explain how these changes were experienced. These associations are the guideposts that organizations can use to identify factors that are key to providing support to the productivity and wellbeing of remote workers.

First, our findings show that employees perceive WFH as having a strong and positive impact on their productivity and creativity in work. This finding is good news for organizations, given that our study is based on a shift to WFH that was abrupt, dramatic in scale, and unplanned due to a pandemic. Presumably, the outcome could be even better for a transition that is deliberate and planned.

The most important factor that explains variation in the productivity index is a (re)alignment in personal values by the individual in adjusting to WFH. Also significant is whether the organization articulates a higher purpose that motivates individuals through the adjustment to WFH. The effect of boundaries (WLI) appears as a separate and significant determinant of productivity, which suggests an interesting, nuanced interpretation. Productivity and creativity are enhanced when individuals identify their work and their organizations with deeper meaning in their lives, and yet when they are still able to maintain boundaries between work and the non-work aspects of their lives. By this interpretation, productivity is supported best when work is close, but not too close.

The positive average effect that the shift to WFH had on productivity was not matched with positive changes in meaning on average. Respondents report experiencing a decrease in meaning and interest in life. Thus, the average effects of the transition to WFH were mixed in the areas of productivity and meaning. They were also mixed in the areas of stress and health—general life stress was perceived as having decreased, while challenges to health increased on average.

Despite the mixed nature across elements of wellbeing, our findings identify a few key sources of friction and support that are common across areas. The intrusion of work into life is a key friction. An important finding is the negative impact of the change in WLI across the board—on productivity/creativity, meaning/interest, general stress in life, and health. The effect is strong, and its impact is significant. It seems, without question, that the intrusion of work into other aspects of living, which occurred on average when work moved home, had significant negative impacts on multiple aspects of workers’ wellbeing. The obvious implication for organizations is that an important priority in supporting remote workers is helping them to set and maintain boundaries between the work and non-work aspects of their lives.

Another important finding is that supportive coworkers play a significant role in the changes to productivity, meaning, and stress. Individuals with supportive coworkers lost out on the positive impact of those coworkers in both work and non-work aspects of their lives as work moved to the home. The implication for employers is to invest in ways that enable remote workers to retain frequent contact with the coworkers by whom they feel supported. Our findings suggest that such investments will pay off in productivity and creativity in work, and also in meaning and interest in life, reduced stress and better health.

A further recommendation that emerges from the analysis is for employers to be deliberate in granting control of time to remote workers. We find that while the intensity of work increased on average, stress did not. The reason workers’ capacity to absorb greater work intensity increased without greater stress is because workers’ control over their time increased when work moved home. Ceding control to workers might have been an unintended consequence of the speed of the transition and lack of planning that organizations were able to do in a pandemic—if employers had planned, they might have retained more control. However, our findings suggest that the ceding of control to workers enabled them to grow in their capacity to absorb greater work intensity. While respondents reported more control, they also reported more accountability, so having more control and flexibility did not diminish their perceptions of accountability.

This finding complements the WLI result—ceding control can mitigate the intrusion of work into non-work aspects of life. However, the implications seem deeper than merely recognizing the value of maintaining boundaries. Deliberately giving control to workers for how they spend their working time makes remote work less stressful and increases remote workers’ capacity to perform at a higher level of intensity. While it is not always easy for supervisors to trust that their employees are doing what they are supposed to be doing when they are not observed, ceding control can actually create greater capacity for work.

Sources of self-support also emerge prominently in our results. The measures of Core Self-Evaluation and Individual Values have significant associations indicating that they contribute to positive changes in productivity and creativity in work and less perceived stress as work shifted home.

Recommendations

-

1

Focus onwhatemployees are getting done and not onwhenthey are doing it. Attempting to maintain the control that one has in the workplace regarding hours or how time is spent is ill advised. Flexibility and control for workers are highly significant contributors to productivity and other aspects of wellbeing.

-

2

Assist employees in maintaining co-worker support. This suggests that investments in communications technology that facilitate contact with supportive coworkers helps both the organization and the individual outside of work. Advances in telepresence technology will assist with this objective while remaining distant is essential for health reasons. In addition, coworker support might also manifest in informal socializing at the workplace, which suggests that employees who work remotely might need times or activities that support informal, non-work related, socializing with coworkers (when WFH becomes part of our work life outside pandemic circumstances). Thereafter, organizations can also create opportunities for coworkers to meet face-to-face periodically to maintain bonds and deepen connections that support their work relationships.

-

3

Managers should assist employees who work remotely in setting boundaries. This could include providing funds to set up a proper home office, computing equipment, and separate communications devices for work and personal lives. Boundaries between work and home are very important. Our results suggest that while increased productivity is associated with greater intensity of work, productivity, meaning, stress, and health are all enhanced by a separation between work and activities that constitute life outside of work.

-

4

Help employees develop their core self-evaluation. CSE is composed of 4 dimensions (locus of control, emotional stability, self-esteem, and self-efficacy). Leaders can give feedback to boost confidence, or assignments to create greater self-efficacy (belief in their abilities). Training, webinars, or even counseling services could also be useful.

-

5

Clearly communicate the organization’s higher purpose. Why are we doing what we are doing and why does it matter? Sadly, many employees go to work every day without a clear understanding of why their work matters. Managers and leaders can make a point of clearly communicating the organization’s purpose particularly when supervising remote workers who are not in the workplace to “absorb” this easily.

-

6

Capitalize on the benefits that can be gained from reduced stress when working from home but take care to address health challenges that may also occur. Consider offering wellness screenings and other types of assistance with health challenges employees may be facing.

-

7

Keep in mind that employees need ways to increase their sense of meaning when life in the workplace disappears. Going to work and being at work and the interactions and stimulation that come from doing so are greatly reduced when employees WFH. Consider encouraging employees to engage in volunteering or giving back, and in engaging in mindfulness exercises. There are a variety of self-help books available on these topics that companies could recommend or actually invest in for their employees.

-

8

Lastly, remember that because you do not see your WFH employees every day or even every month, they are still on the front lines keeping your business running and they need encouragement, support, and care.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study. Degree of contribution is indicated by author order.

Selected bibliography

For those interested in literature examining remote work, see Bailey and Kurland’s (2002) “A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work” in the Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(4), 383-400. See also, De Menezes and Kelliher’s (2011) “Flexible working and performance: A systematic review of the evidence for a business case” in International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(4), 452-474.

For further reading on scales used in our survey, please see Probst and colleagues’ (2007) “Counterproductivity and creativity: The ups and downs of job insecurity” in the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(3), 479-497; Schmidt and colleagues’ (2014) “Associations between supportive leadership and employees self-rated health in an occupational sample” in the International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(5), 750-756; and Judge and colleagues’ (2003), “The core self‐evaluations scale: Development of a measure” in Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303-331.

For additional statistics on telework and work from home trends since the onset of the pandemic, see “Latest Work-At-Home/Telecommuting/Mobile Work/Remote Work Statistics” Global Workplace Analytics (2020), https://globalworkplaceanalytics.com/telecommuting-statistics. See also, Brynjolfsson and colleagues’ (2020), “COVID-19 and remote work: an early look at US data” (No. w27344) from the National Bureau of Economic Research. And Bloom’s (2020) “How working from home works out” from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, https://siepr.stanford.edu/research/publications/how-working-home-works-out.

Biographies

Thomas J. George, Ph.D. is C.T. Bauer Professor of Finance, Director, AIM Center for Investment Management, at the C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston, 4800 Calhoun Rd, Houston, TX 77204 (Tel.: 713 743 4762, e-mail: tom-george@uh.edu).

Leanne E. Atwater, Ph.D. is C.T. Bauer Professor of Leadership and Management, Department of Management and Leadership, at the C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston, 4800 Calhoun Rd, Houston, TX 77204 (Tel.: 713 743 6884, e-mail: leatwater@uh.edu). (Corresponding author).

Dustin Maneethai, M.S. is a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Psychology, 4800 Calhoun Rd, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204 (Tel.: (714) 331-2993, e-mail: dmaneeth@gmail.com).

Juan M. Madera, Ph.D. is Professor at the Conrad N. Hilton College, University of Houston, 4450 University Dr, Houston, TX 77204 (Tel.: 713 743 2428, e-mail: jmmadera@central.uh.edu).

Footnotes

It should be noted that we cannot disentangle the effects of the health-related aspects of the pandemic from working from home. However, all of our survey questions directly referenced working from home.