Abstract

A comparison was done of 231 strains of birnavirus isolated from fish, shellfish, and other reservoirs in a survey study that began in 1986 in Galicia (northwestern Spain). Reference strains from all of the infectious pancreatic necrosis virus serotypes were included in the comparison, which was done by neutralization tests and agarose and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the viral genome. The neutralization tests with antisera against the West Buxton, Spajarup (Sp), and Abild (Ab) strains showed that most of the Galician isolates were European types Sp and Ab; however, many isolates (30%) could not be typed. Results from agarose gels did not provided information for grouping of the strains, since all were found to have genomic segments of similar sizes. Analysis of polyacrylamide gels, however, allowed six electropherogroups (EGs) to be differentiated on the basis of genome mobility and separation among segments, and a certain relationship between EGs and serotypes was observed. A wide diversity of electropherotypes was observed among the Galician isolates, and as neutralization tests showed, most of the isolates were included in EGs corresponding to European types Ab and Sp. Only 6.5% of the isolates had the electropherotype characteristic of American strains.

In the last 2 decades, the culture of molluscs and fresh- and saltwater fish has become very important in Galicia (northwestern Spain) in terms of the economy and in providing employment. Since the middle of the 1980s, our laboratory has conducted viral surveys of turbot, trout, and salmon from farms located in the area, as well as other reservoirs of viruses, including molluscs, wild fish and sediments around fish farms. During this study, a great number of viruses have been isolated from fish farms (17) and reservoirs (27) and most have been identified as belonging to the family Birnaviridae and being related to the infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV).

IPNV is the etiological agent of a highly infectious disease of several species of wild and cultured aquatic organisms (11). Birnaviruses have a bisegmented double-stranded RNA genome, and segments A and B, respectively, have molecular masses of 2.5 and 2.3 MDa. Although mainly affecting young salmonids, birnaviruses have also been detected in nonsalmonid fishes (3, 13, 29), as well as in molluscs (20, 22, 27) and crustaceans (2). However, most of the strains isolated from invertebrates were nonpathogenic to the host.

It may be that the existence of a wide range of hosts for this virus is the reason for the large number of strains described. Classification of IPNV strains has traditionally been established by means of serological techniques. Throughout the last decade, only three serological types of strains were recognized, of which two are considered typically European (serotypes Sp and Ab) and the other is considered typically North American (serotype VR-299) (14, 19, 23, 30). Due to the large number and diversity of new viral strains reported, many discrepancies in that serological classification came out (11). Recently, Hill and Way (11; B. J. Hill and K. Way, Abstr. 1st Int. Conf. EAFP, p. 10, 1983; B. J. Hill and K. Way, Abstr. Int. Fish Health Conf., p. 151, 1988) have demonstrated that the aquatic birnaviruses are distributed worldwide in two serogroups (A and B), with up to 10 serotypes (9 and 1, respectively). Other authors, employing monoclonal antibodies, found a pattern of serological relationships similar to that shown by Hill and Way (11; Hill and Way, abstr. IFHC), who used polyclonal antibodies, as recently reviewed by Reno (26). Furthermore, some authors have compared the electropherotypes of viral polypeptides and genomes for typing of IPNV strains (9, 10, 12) and have observed a certain relationship with serotyping. In the present study, a large number of IPNV strains isolated from several fish farms and viral reservoirs in Galicia were compared in order to study the diversity of strains of this virus in the area.

Cell lines and viral strains.

Monolayers of the CHSE-214 cell line were grown at 15°C in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin at 100 U/ml, and streptomycin at 100 μg/ml. Viral strains were propagated in confluent monolayers at 15°C in minimum essential medium without fetal bovine serum.

For comparison, the following 25 reference strains belonging to both serogroups of IPNV (11) were analyzed: strain TV-1 of serotype B1; 10 strains of serotype A1, including the representative WB (West Buxton) strain; 4 strains of serotype A2, including the representative Sp (Spajarup) strain; Ab (Abild), EVE, and CVHB-1 of serotype A3; He (Hecht) of serotype A4; Te-2 (tellina virus) of serotype A5; C1 (Canada 1) and AS (Atlantic salmon) of serotype A6; C2 of serotype A7; C3 of serotype A8; and Ja (Jasper) of serotype A9.

The Galician IPNV isolates (a total of 231 isolates) were obtained from two main sources: (i) 176 strains isolated from fish farms from both epizootics and routine surveys (28 from rainbow trout [Oncorhynchus mykiss], 6 from Atlantic salmon [Salmo salar], and 12 from turbot [Scophthalmus maximus]) and (ii) 55 IPNV-like strains isolated from environmental reservoirs sampled near the affected fish farms. These environmental reservoirs comprised (i) molluscs, including mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis; 32 isolates), oysters (Crassostrea gigas; 5 isolates), and periwinkles (Littorina littorea; 4 isolates); (ii) wild fish, such as sand eels (Ammodytes sp.; 6 isolates), blue whiting (Micromesistius poutasou, 1 isolate), and sprat (Sprattus sprattus; 1 isolate), which are used as food for cultured turbot; and (iii) marine sediments (5 isolates) and moist food pellets (1 isolate). Part of these isolates were previously reported by Ledo et al. (17) and Rivas et al. (27). However, most of them correspond to unpublished isolations performed as described by those authors.

Virus purification and antisera.

The Sp, Ab, and WB viral strains were purified in order to obtain specific antisera. For this purpose, 20 flasks of 150 cm2 were inoculated at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 to 0.01 and when cytopathic effects were extensive, cells were scraped into the medium and cell debris was pelleted at 1,500 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was supplemented with 8% polyethylene glycol (PEG; molecular weight, 20,000). Pelleted cell debris was resuspended in 10 ml of 1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) mixed with 1 volume of Freon, and the mixture was shaken vigorously for 5 min. The resultant emulsion was separated into Freon and aqueous phases by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was transferred to the former PEG suspension. After incubation overnight at 4°C, the PEG-virus complex was pelleted at 8,000 × g for 20 min and resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) supplemented with 0.2% Tween 20. An equal volume of Freon was added, the mixture was shaken vigorously for 5 min, and virions were collected from the aqueous phase as described above and pelleted by centrifugation for 90 min at 10,000 × g, resuspended in 0.5 ml of 1× SSC, layered onto a 10 to 50% continuous sucrose gradient, and centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 1 h. The visible virus band was collected and concentrated by centrifugation (150,000 × g for 90 min), and the purified virus was resuspended in 500 μl of 1× SSC and stored at 4°C until use.

The antisera were obtained by inoculating young New Zealand White rabbits with purified virus in accordance with the schedule previously reported by Dopazo et al. (5) for aquareovirus.

Neutralization test.

For serological characterization of the Galician IPNV isolates, the neutralization test was applied with antisera against the Sp, Ab, and WB serotypes. The neutralization test was carried out basically as described by Okamoto et al. (23). The viruses were diluted in Earle's buffer to a titer of approximately 103 50% tissue culture-infective doses/ml. The antisera were diluted from 1/10 to 1/100,000 in Earle's buffer, and virus and antiserum dilutions were mixed (1:1). After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, the mixtures were inoculated into three wells (100 μl/well) of confluent CHSE-214 cells in 96-well plates. The plates were incubated at 15°C for a maximum period of 15 days. The neutralization antibody titers were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (25) and expressed as the reciprocal of the highest antiserum dilution protecting 50% of the inoculated wells. The antigenic relatedness of the Galician isolates with the three serotypes (Sp, Ab, and WB) was determined as the ratio of the homologous to the heterologous titers. The closer the ratio was to 1, the higher the relatedness with the corresponding serotype.

When reciprocal cross-neutralization was possible (i.e., among the three reference strains [Sp, Ab, and WB]), the degree of antigenic relatedness was calculated and interpreted as suggested by Hill and Way (11). As expected, the three antisera showed higher neutralization titers with the corresponding homologous type strain than with a heterologous strain (data not shown). Furthermore, cross-neutralization ratios were higher than 10 among the three antisera: ratios of 32 and 80 were obtained when WB was compared with Ab and Sp, respectively, and between Sp and Ab, the ratio was 11.

Most of the isolates showed higher relatedness with the European serotypes. As shown in Table 1, 128 isolates (55%) showed a ratio of antigenic relatedness of 1 to 2 with European serotype Sp, and more than 30% (71 strains) showed antigenic relatedness with serotype Ab. However, it must be pointed out that some strains (29%; data not shown) gave ratios of 1 to 2 with both serotypes. Only one isolate gave a ratio of 1 to 2 with serotype WB. A large number of isolates (30%) gave low antigenic relationships (ratio higher than 4) with all three antisera. Therefore, use of neutralization has demonstrated that most of the Galician isolates were closely related to the European strains and we were not able to demonstrate a great diversity among them. Perhaps the use of antisera against the 10 serotypes would be more appropriate to determine the serotype of those strains not typed with any of the three antisera. Furthermore, as pointed out by other authors (24), a complete analysis of the serological relationships among viruses requires cross-neutralization tests. However, although these possibilities were taken into consideration, due to the large number of isolates included in this study, they were not applied.

TABLE 1.

Antigenic relatedness of Galician IPNV isolates with the WB, Ab, and Sp serotypes

| Ratiosa | Antiserum

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| WB | Sp | Ab | |

| 1–2 | 1b | 128 | 71 |

| 3–4 | 5 | 32 | 10 |

| 5–9 | 19 | 4 | 45 |

| 10–100 | 135 | 64 | 80 |

| >100 | 71 | 3 | 25 |

| Totalc | 231 | 231 | 231 |

Antigenic relatedness, calculated as the ratio of the homologous to the heterologous titers.

Number of Galician isolates showing the corresponding ratio.

Total number of isolates.

Comparison of electropherotypes.

For agarose and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, each viral strain was inoculated into a 75-cm2 flask of confluent CHSE-214 cells and when the cytopathic effect was extensive, the viral suspension was clarified by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were pelleted for 1 h at 78,000 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 1× SSC buffer and sonicated for 30 s (at 20 kHz). Virions were cleaned by centrifugation through a 30% sucrose cushion for 1 h at 100,000 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 1× SSC. The final concentration was achieved by centrifugation at 150,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C, and the virus was resuspended in 50 μl of 1× SSC buffer and stored at −20°C until use. Prior to electrophoresis, concentrated virus was subjected to digestion with proteinase K at 2 mg/ml in the presence of 0.5% SDS at 65°C for 2 h. The viral genome was extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and ethanol precipitated overnight at −20°C. The pellets were vacuum dried in a Speedvac (Savant) for about 5 min and resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA).

Horizontal agarose gel electrophoresis was performed on 0.5% agarose gels containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml at 100 V for 2 h. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was carried out in 6% polyacrylamide vertical slab gels (16) at 150 V for 16 h and revealed by staining with ethidium bromide. In both cases, molecular weights were determined by comparison with the turbot aquareovirus TRV RNA segments which were used as markers.

Different percentages of agarose gels were tested, from 0.5 to 1.2%, and the best results, in terms of separation of the bands, were achieved with the 0.5% agarose gels (results not shown). The molecular masses of A and B segments were around 1.98 × 106 and 1.82 × 106 Da, respectively. As expected, no variability in the genome mobility of the Galician IPNV isolates and reference strains was observed in agarose gels. This is easily explained, as mobility basically depends on the sizes of the double-stranded RNAs, which do not differ by large numbers of base pairs.

One interesting result was the difference in the molecular masses observed with the different electrophoretic techniques: polyacrylamide gels gave molecular masses 0.1 to 0.2 MDa higher than those obtained with agarose gels. These differences are due to the different ways that nucleic acid migrates in the two types of gel (1). The sizes of the genomic segments in polyacrylamide gels ranged from 1.99 × 106 to 2.14 × 106 Da for segment A and from 1.92 × 106 to 2.02 × 106 Da for segment B, which also differed from the values reported by other authors (4, 9, 10, 12, 28). This was probably due to the different percentages of acrylamide-bisacrylamide and/or the different molecular weight standards employed. As shown at Fig. 1, using polyacrylamide gels produced a noticeable divergence among the genomic profiles of the IPNV strains assayed. Those differences included the mobility of the segments and also their separation: narrow patterns (with relatively small differences in molecular weight between segments), such as the one shown by the Ja strain, could be easily differentiated from the wide patterns (with larger differences between segments) shown, e.g., by strains WB and Ab. Among these, differences were also observed in the sizes of the segments, i.e., in their mobility (the Ab genome clearly showed higher mobility than the WB genome).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of RNA patterns of the genomes of IPNV isolates from fish and other reservoirs with those of reference type strains using SDS–6% polyacrylamide gels. The values on the left are the molecular masses of the genomic segments of the turbot aquareovirus TRV, expressed in megadaltons.

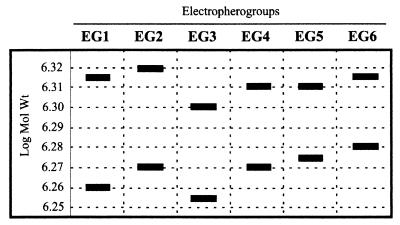

Electrophoresis of the genome in polyacrylamide gels has been found by us to be an easy, fast, and powerful technique for comparison of IPNV strains. Based on the mobility of segments and the separation among them, six different electropherotypes, which we named electropherogroups (EGs), were established (Fig. 2). It is important to point out that a certain relationship was observed between the EGs and the serotypes of serogroup A. EG3, -5, and -6 were represented by serotypes A3 (including strains Ab, EVE, and CVHB-1), A4 (strain Hecht), and A9 (strain Jasper), respectively (Table 2). Serotypes A2 (including strains Sp, d'Honnincthum, Bonamy, and N1) and B1 (represented by tellina virus strain TV-1) were included in EG4. EG2 was even more complex, since it included several serotypes, comprising the American WB type strain (serotype A1); Canadian strains C1, C2, and C3 (serotypes A6, A7, and A8); and strain Te-2, isolated in the United Kingdom from a mollusc (serotype A5). Moreover, it must be noted that the two reference strains isolated from the Tellina mollusc (Te-2 and TV-1, corresponding to serotypes A5 and B1, respectively) showed distinctive electropherotypes (EG2 and -4, respectively). None of the reference strains was included in EG1.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the electropherotypes obtained from reference strains and Galician isolates and the EGs established.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of the Galician IPNV isolates and reference strains among the six EGs established by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the viral genome

| Virus characteristic or source | EG1 | EG2 | EG3 | EG4 | EG5 | EG6 | Total no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference strains | |||||||

| No. of strains | 0 | 15a | 3b | 5c | 1d | 1e | 25 |

| Serotype(s) | A1, A5, A6, A7, A8 | A3 | A2, B1 | A4 | A9 | ||

| Fish farm isolates | |||||||

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | 2 | 11 | 5 | 76 | 15 | 109 | |

| Scophthalmus maximus | 11 | 27 | 6 | 44 | |||

| Salmo salar | 2 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 20 | ||

| Oncorhynchus kitsutch | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Salmo trutta fario | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Anguilla anguilla | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total no. of fish isolates | 2 | 13 | 22 | 115 | 24 | 0 | 176 |

| Reservoir isolates | |||||||

| Mytilus galloprovincialis | 18 | 14 | 32 | ||||

| Crassostrea gigas | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Littorina littorea | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Ammodytes sp. | 2 | 4 | 6 | ||||

| Sprattus sprattus | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Micromesistius poutassou | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Moist fish pellets | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Marine sediments | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Total no. of reservoirs | 0 | 2 | 21 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 55 |

| Total no. (%) of isolates | 2 (0.9) | 15 (6.5) | 43 (18.6) | 147 (63.6) | 24 (10.4) | 0 | 231f |

Including strains WB, VR-299, R, PM, Bh, DM, Br, Mh, SB, CTT (serotype A1), Te-2 (serotype A5), C1, AS (serotype A6), C2, and C3 (serotypes A7 and A8, respectively).

Including strains Ab, EVE, and CVHB-1.

Including strains Sp, d'H, B, N1 (serotype A2), and TV-1 (serotype B1).

Including the He strain.

Including the Ja strain.

Total number of fish farm and reservoir isolates.

Based on our results, it seems clear that analysis of IPNV genome profiles can help in the differentiation of serotypes, although the technique must be complemented by others in order to distinguish serotypes with the same electropherotype. Hedrick et al. (7, 9, 10) reported that a combined analysis of the electrophoretic profile of RNA genome segments and virion polypeptides can distinguish different IPNV strains. However, they suggested that mobility of the virion polypeptides is a more suitable basis for grouping of new isolates. Other authors (6) also reported the use of genomic electropherotypes as a means by which new strains of IPNV could be identified.

Among the Galician isolates, a wide diversity of electropherotypes was observed. They were distributed among EG1 to -5 (Table 2), and none of them showed the narrowest electropherotype (EG6). Although most of the isolates belonged to EG4 (63.6%), the remaining EGs (except EG6) contained a variable number of isolates: 0.9% in EG1, 6.5% in EG2, 18.6% in EG3, and 10.4% in EG5. As regards the isolates from fish farms, most of them (115 strains, i.e., more than 65%) belonged to EG4. Around 12.5% (22 strains) of the isolates from fish were included in EG3, and 13.5% were in EG5 (24 strains). Thirteen strains showed the wide pattern typical of EG2, and only two strains were included in the widest EG (EG1). Of the strains isolated from different types of reservoirs, the majority were in EG3 and -4. Only two isolates, one from L. littorea (periwinkles) and a strain isolated from moist fish pellets (prepared with raw fish), showed the pattern characteristic of EG2. It is interesting that none of the reservoir strains were included in the group with the widest pattern (EG1) or in the groups with the narrowest patterns (EG5 and -6). This wide diversity among the strains isolated in our area can be explained by the fact that when our laboratory began its work in diagnosis, the importation of eggs or fish from other European countries, as well as from North America and Australia, was a common practice among fish farms.

Other authors have published similar studies of comparisons of IPNV strains by neutralization and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, although they reported lower levels of divergence. Hedrick et al. (9) reported the analysis of four birnaviruses isolated from fish in Taiwan; three of them were closely related to the Ab strain, and the fourth was related to serotype VR-299. Hsu et al. (12, 13) studied a larger number of strains, also from Taiwan, all of them related to the Ab or the VR-299 serotype. Moreover, another four viruses isolated from fish in Korea were found to be closely related to reference strain VR-299 (8). In another report, Kusuda et al. (15) compared six Japanese IPNV isolates with the Ab, Sp, and VR-299 type strains, concluding that the Japanese strains constituted a completely separate group. However, all of these reports have in common the lack of use of reference strains from the 10 serotypes. Other authors, such as Lee et al. (18), used other molecular techniques to compare a relatively large number of strains, but even then the study did not include strains from the 10 serotypes.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that such a large number of isolates of IPNV from a specific area has been included in a study and compared with reference strains of all of the IPNV serotypes. Nevertheless, further experiments are being carried out to compare these strains using other techniques (such as restriction fragment length polymorphism and sequencing) in order to confirm the diversity of the strains and establish groups of similarity among them.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant AGF93-0769-C02-01 from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia and grant XUGA 20009B96 from the Xunta de Galicia, Spain.

We thank B. L. Nicholson, C.-F. Lo, and R. P. Hedrick for supplying viral strains. J. M. Cutrin acknowledges the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Spain) for research fellowships.

Footnotes

Scientific contribution 0003/99 of the Instituto de Acuicultura.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bovo G, Ceschia G, Giorgetti G, Vanelli M. Isolation of an IPN-like virus from adult Kuruma shrimp (Penaeus japonicus) Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 1984;4:21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S N, Kou G H, Hedrick R P, Fryer J L. The occurrence of viral infections of fish in Taiwan. In: Ellis A E, editor. Fish and shellfish pathology. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1985. pp. 313–319. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobos P. The molecular biology of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1995;5:25–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dopazo C P, Toranzo A E, Samal S K, Roberson B S, Baya A, Hetrick F M. Antigenic relationship among rotaviruses isolated from fish. J Fish Dis. 1992;15:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganga M A, González M P, López-Lastra M, Sandino A M. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of viral genomic RNA as a diagnostic method for infectious pancreatic necrosis virus detection. J Virol Methods. 1994;50:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedrick R P, Eaton W D, Fryer J L, Groberg W G, Jr, Boonyaratapalin S. Characteristics of a birnavirus isolated from cultured sand goby Oxyeleotris marmoratus. Dis Aquat Org. 1986;1:219–225. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedrick R P, Eaton W D, Fryer J L, Hah Y C, Park J W, Hong S W. Biochemical and serological properties of birnaviruses isolated from fish in Korea. Fish Pathol. 1985;20:463–468. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedrick R P, Fryer J L, Chen S N, Kou G H. Characteristics of four birnaviruses isolated from fish in Taiwan. Fish Pathol. 1983;18:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedrick R P, Okamoto N, Sano T, Fryer J L. Biochemical characterization of eel virus european. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:1421–1426. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-6-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill B J, Way K. Serological classification of infectious pancreatic necrosis (IPN) virus and other aquatic birnaviruses. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1995;5:55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu Y-L, Chen B-S, Wu J-L. Comparison of RNAs and polypeptides of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus isolates from eel and rainbow trout. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2233–2239. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-8-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu Y-L, Hong J-L, Wu M-F, Wu J-L. Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus infection in Taiwan's aquatic fishes. Fish Soc Taiwan. 1993;20:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jørgensen P E V, Kehlet N P. Infectious pancreatic necrosis (IPN) viruses in Danish rainbor trout: their serological and pathogenic properties. Nord Vet Med. 1971;23:568–575. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusuda K, Nishi Y, Hosono N, Suzuki S. Serological comparison of birnaviruses isolated from several species of marine fish in southwest Japan. Fish Pathol. 1993;28:91–92. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–684. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledo A, Lupiani B, Dopazo C P, Toranzo A E, Barja J L. Fish viral infections in Northwest of Spain. Microbiol SEM. 1990;6:21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee M-K, Blake S L, Singer J T, Nicholson B L. Genomic variation of aquatic birnaviruses analyzed with restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2513–2520. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2513-2520.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald R D, Gower D A. Genomic and phenotypic divergence among three serotypes of aquatic birnaviruses (infectious pancreatic necrosis virus) Virology. 1981;114:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAllister P E, Bebak J. Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus in the environment: relationship to effluent from aquaculture facilities. J Fish Dis. 1997;20:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortensen S H. Commercially exploited bivalve molluscs in Norway. Their health status and potential role as vectors of the fish pathogenic infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV). Ph.D. thesis. Bergen, Norway: University of Bergen; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortensen S H. Passage of infectious p virus (IPNV) through invertebrates in an aquatic food chain. Dis Aquat Org. 1993;16:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto N, Sano T, Hedrick R P, Fryer J L. Antigenic relationships of selected strains of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus and European eel virus. J Fish Dis. 1983;6:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olesen N J, Lorenzen N, Jørgensen P E V. Serological differences among isolates of viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus detected by neutralizing monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Dis Aquat Org. 1993;16:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed L J, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reno P W. Infectious pancreatic necrosis and associated aquatic birnaviruses. In: Woo P T K, Bruno D W, editors. Fish diseases and disorders, vol. 3. Viral, bacterial and fungal infections. New York, N.Y.: CABI Publishing; 1999. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivas C, Cepeda C, Dopazo C P, Novoa B, Noya M, Barja J L. Marine environment as reservoir of birnaviruses from poikilothermic animals. Aquaculture. 1993;115:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephens E B, Hetrick F M. Molecular characterization of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus isolated from a marine fish. In: Crosa J H, editor. Bacterial and viral diseases of fish. Molecular studies. Seattle: Washington University; 1983. pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolf K. Fish viruses and fish viral diseases. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press; 1988. pp. 115–157. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolf K, Quimby M C. Salmonid viruses: infectious pancreatic necrosis virus. Morphology, pathology and serology of first European isolations. Arc Gesamte Virusforsch. 1971;34:144–156. doi: 10.1007/BF01241716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]