Abstract

Medium-chain-length (mcl) poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) are storage polymers that are produced from various substrates and accumulate in Pseudomonas strains belonging to rRNA homology group I. In experiments aimed at increasing PHA production in Pseudomonas strains, we generated an mcl PHA-overproducing mutant of Pseudomonas putida KT2442 by transposon mutagenesis, in which the aceA gene was knocked out. This mutation inactivated the glyoxylate shunt and reduced the in vitro activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase, a rate-limiting enzyme of the citric acid cycle. The genotype of the mutant was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the phenotype was confirmed by biochemical experiments. The aceA mutant was not able to grow on acetate as a sole carbon source due to disruption of the glyoxylate bypass and exhibited two- to fivefold lower isocitrate dehydrogenase activity than the wild type. During growth on gluconate, the difference between the mean PHA accumulation in the mutant and the mean PHA accumulation in the wild-type strain was 52%, which resulted in a significant increase in the amount of mcl PHA at the end of the exponential phase in the mutant P. putida KT217. On the basis of a stoichiometric flux analysis we predicted that knockout of the glyoxylate pathway in addition to reduced flux through isocitrate dehydrogenase should lead to increased flux into the fatty acid synthesis pathway. Therefore, enhanced carbon flow towards the fatty acid synthesis pathway increased the amount of mcl PHA that could be accumulated by the mutant.

Many bacteria are able to accumulate poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) as carbon and energy reserves. Because of their potential use as biodegradable thermoplastics and as biopolymers that can be produced from renewable resources, PHAs have been extensively studied by academic and industrial groups (2, 6, 30). Pseudomonads synthesize mainly medium-chain-length (mcl) PHAs, which consist of monomers containing 6 to 14 carbon atoms (8, 14, 31). Although a few PHAs have been developed commercially and marketed (6, 11), widespread use of these polymers has been hindered by high production costs (1, 19). Reduction of these costs could be achieved by several means, including increasing the product yield (19) or using transgenic plants for PHA production, provided that PHA levels can be brought to 20 to 40% of the plant dry weight (23, 24, 32).

During the past few years we have constructed several sets of mutants of Pseudomonas putida KT2442 with the goal of altering the carbon flux towards mcl PHAs. While most of these mutants contain clearly reduced mcl PHA levels, a few have exhibited increased PHA production. Preliminary analysis of one of these mutants (P. putida KT217) showed that its glyoxylate pathway was affected.

From studies on P. putida KT2442, it is known that PHA precursors can be produced via the following three main pathways: β-oxidation, de novo fatty acid biosynthesis, and elongation of 3-hydroxyalkanoates by acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) molecules (12, 32). The β-oxidation pathway is active during growth on fatty acids, whereas during growth on carbohydrate or carbohydrate-derived substrates, such as sugars or gluconate, PHA precursors are generated via the fatty acid synthesis pathway (13). Therefore, when cells are grown on gluconate, acetyl-CoA is a key intermediate of the PHA biosynthesis pathway, and since acetyl-CoA plays an essential role in replenishing both the citric acid cycle and the fatty acid synthesis pathway, PHA synthesis competes with the citric acid cycle for acetyl-CoA. To decrease the flux of acetyl-CoA into the citric acid cycle, either the level of citrate synthase expression or the concentration of oxaloacetate should be lowered. The intracellular concentration of oxaloacetate can be reduced by cutting off the supply of its direct precursor, malate, by blocking the glyoxylate pathway, and/or by preventing processing of isocitrate by reducing isocitrate dehydrogenase activity. Therefore, inactivation of the glyoxylate pathway and downregulation of isocitrate dehydrogenase should result in an increase in the overall flux of acetyl-CoA into mcl PHA production.

In this paper we describe mutant P. putida KT217, which is affected in the glyoxylate pathway. We also describe the potential of isocitrate lyase and the citric acid cycle for increasing mcl PHA levels in P. putida.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

P. putida KT2442 (3) is a strain which was derived from P. putida mt2, is cured of the TOL plasmid, and is able to produce mcl PHA from various substrates. P. putida KT217 is an aceA knockout mutant of P. putida KT2442 that was generated in this study. Escherichia coli JM109 (38), HB101 (25), and S17-λpir (20) were also used, as were plasmids pGEc404 (15), pRK600 (7), pUC18 (38), and pUT mini-Tn5 tet (7).

Pseudomonas cells were grown at 30°C in minimal medium 0.1 N E2 (17) supplemented with gluconate or a mixture of gluconate and heptanoate as indicated below. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in complex Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (25). Cells were grown in Erlenmeyer flasks and incubated at 225 rpm. The following antibiotics were added as needed: 12.5 μg of tetracycline per ml and 30 μg of rifampin per ml. Media were solidified with 1.5% (wt/vol) agar for plate experiments. Cell dry weight was determined gravimetrically (10) and spectrophotometrically at 450 nm (36). Cultures were harvested by centrifugation and were washed with 10 mM MgSO4. To determine amounts of PHA, the cell pellets were lyophilized.

DNA manipulation.

Basic recombinant DNA techniques, such as preparation and purification of plasmid DNA, restriction endonuclease digestion, agarose gel electrophoresis, and transformation of E. coli, were performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. (25).

Transposon mutagenesis was performed as described previously (7).

Southern blot analysis was performed by using a 2-kb tet gene fragment obtained by SmaI digestion of pUT mini-Tn5 tet (7). The probe was labeled by using a DIG labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

DNA sequencing and analysis of sequence data.

DNA sequencing was performed with denatured double-stranded plasmid DNA by using an Amersham Thermosequenase fluorescently labeled primer cycle sequencing kit. Standard primers (pUC18/19-40 forward primer and -40 reverse primer) and primers binding to the mini-Tn5-derived tetracycline gene (primer A [5′-GATGTTACCCGAGAGCTTACC-3′] and primer B [5′-TAAGCGTGCATAATAAGCCCTACA-3′]) were used. A homology search was performed by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) programs.

PHA determination.

PHA amounts and compositions were determined as described previously (16).

Enzyme assays.

Pseudomonas cells were prepared as spheroplasts (37) and were opened by two passages through a French pressure cell (20,000 lb/in2). Isocitrate lyase activity was assayed by coupling the formation of glyoxylate and the subsequent reduction of glyoxylate to glycolate with oxidation of NADH with lactate dehydrogenase (9). Each cuvette contained, in a final volume of 1 ml, 50 mM MOPS (morpholine propanesulfonic acid)-NaOH (pH 7.3), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dl-isocitrate, 0.2 mM NADH, and 0.1 mg of pig heart lactate dehydrogenase per ml. The isocitrate lyase activity level was corrected for non-isocitrate lyase-related NADH oxidation by subtracting the level of activity in controls in which isocitrate was omitted. The level of isocitrate dehydrogenase activity was measured by monitoring the ability of the enzyme to reduce NADP. Each cuvette contained, in a final volume of 1 ml, 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.3), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dl-isocitrate, and 0.2 mM NADP. The isocitrate dehydrogenase activity level was corrected for non-isocitrate dehydrogenase-related NADP reduction by subtracting the level of activity found in controls in which isocitrate was omitted. Protein concentrations were measured by using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). All enzyme activities were assayed at 37°C, and specific activities were expressed per milligram of crude supernatant protein. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of protein necessary to convert 1 μmol of isocitrate per min.

Flux analysis. (i) Setup of metabolic network.

The biochemical reaction network for P. putida shown in Fig. 1 was constructed on the basis of previously described data (29) and on the basis of the results of a sequence analysis of the P. aeruginosa genome in the EMP database (http://wit.mcs.anl.gov/WIT2) (27, 28). Serial reaction steps were considered by examining lumped reactions (several reactions were combined in one equation). The stoichiometric matrix was formulated accordingly. Based on thermodynamics and typical intracellular metabolite concentrations, the reactions catalyzed by the following enzymes were considered to be physiologically irreversible: pyruvate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, 2-oxoglutarate synthase, malic enzyme, malate synthase, the respiratory reaction, and gluconokinase. Boundaries were imposed so that irreversible reactions had nonnegative fluxes. The reaction from acetyl-CoA to mcl PHA was assumed to consist of the appropriate reactions of the fatty acid synthesis cycle and the polymerization reaction from 3-hydroxy acyl-CoA to the polymer. Conversion of NADPH to NADH via the transhydrogenase reaction was assumed to be reversible (35). The precursor requirements for biomass formation were obtained from Physiology of the Bacterial Cell: a Molecular Approach (22), with the modifications proposed by Sauer et al. (26).

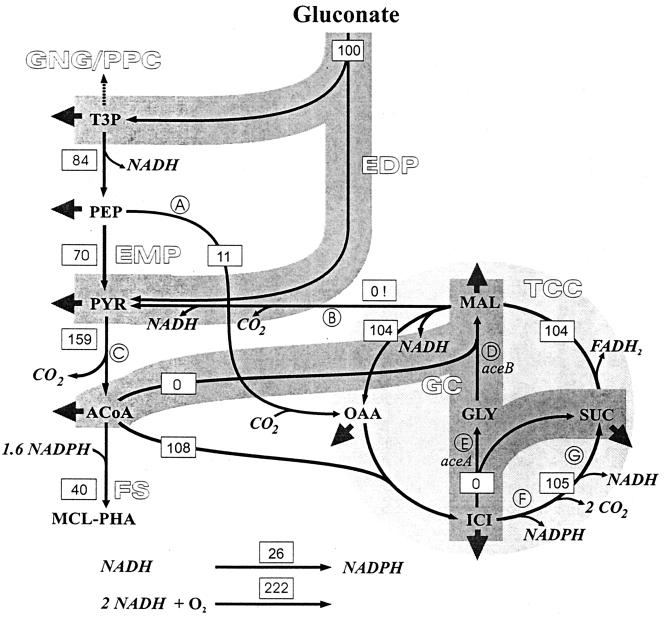

FIG. 1.

Flux distribution for P. putida KT217 during exponential growth on gluconate. The flux values (values in boxes) are expressed as percentages of the specific gluconate uptake rate. It is thought that malic enzyme uses NAD as a cofactor. Gluconeogenetic reactions and the nonoxidative branch of the pentose phosphate cycle are not shown. Abbreviations: EDP, Entner-Doudoroff pathway; EMP, glycolysis; FS, fatty acid biosynthesis; GC, glyoxylate cycle; GNG, gluconeogenesis; PPC, pentose phosphate cycle; TCC, citric acid cycle; A, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; B, malic enzyme; C, pyruvate dehydrogenase; D, malate synthase; E, isocitrate lyase; F, isocitrate dehydrogenase; G, 2-oxoglutarate synthase; T3P, triose 3-phosphate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR, pyruvate; ACoA, acetyl-CoA; OAA, oxaloacetate; GLY, glyoxylate; ICI, isocitrate; SUC, succinate; MAL, malate. FADH2 is treated like NADH.

The principles of stoichiometric flux analysis have been extensively described previously (33). Specific metabolite concentrations can be balanced according to the dynamic flux balance

|

1 |

where x is the metabolite concentration, S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the intracellular reaction flux, and b is the withdrawal flux from the reaction system. Assuming that balanced growth occurs in the exponential growth phase of batch cultures, the dynamic flux balance (equation 1) reduces to the quasi steady-state balance

|

2 |

The dimension of the stoichiometric matrix was 22 × 22 with rank 20. The carbon dioxide and the oxygen balance were excluded. The flux through malic enzyme was assumed to be negligible (21), and the glyoxylate shunt was found to be inactive in the case of mutant strain KT217, which reduced the dimension of the stoichiometric matrix to 20 × 20 with rank 20, indicating that it was a determined system. The linear equation system was solved by using the linprog function from the MATLAB Optimization Toolbox (5). In case of wild-type strain KT2442, the system was underdetermined due to an active glyoxylate shunt, which did not allow us to solve the system for an unambiguous solution.

(ii) Solving the flux model.

In order to examine the stoichiometric dependence between fluxes of isocitrate dehydrogenase and specific mcl PHA production in wild-type and mutant strains, the complete system was considered without any constraints on the malic enzyme reaction and, in the case of the wild-type strain, glyoxylate shunt activity. In this case minimization of substrate conversion to PHA was used as an objective function.

RESULTS

Preparation of transposon mutant P. putida KT217.

Cells that were mutagenized with the mini-Tn5 tet transposon were screened on medium 0.1 N E2 containing 15 mM octanoate, 30 μg of tetracycline per ml, and traces of LB medium. Colonies which grew poorly compared to wild-type colonies were plated onto gluconate-containing medium. Cells which grew slowly on octanoate-containing medium supplemented with traces of LB medium and grew normally on gluconate-containing medium were selected for further analysis. Six clones were selected from 15,000 colonies and characterized in more detail. To determine whether the observed phenotype of the mutants was due to insertion of mini-Tn5 tet into the bacterial chromosome, hybridization experiments were carried out. Chromosomal DNA of the six mutants were digested with KpnI and hybridized with the labeled fragment of the tet gene (data not shown). Since the mutants showed hybridization in Southern blot experiments, they were used for further characterization. One of the putative mutants, designated KT217, was not able to utilize acetate and other mcl fatty acids, such as hexanoic acid or decanoic acid, as sole carbon sources and was used for further analysis.

Characterization of the genotype of KT217.

Chromosomal DNA of mutant KT217 was digested with KpnI and ligated into KpnI-digested pUC18. Tetracycline-resistant clones contained an insert that was approximately 5.8 kb long. The nucleotide sequences of the transposon flanking regions were determined by DNA sequencing. To determine the gene or chromosomal DNA stretch into which the mini-Tn5 tet transposon was integrated, a homology search was performed with the nucleotide sequences obtained. The two transposon flanking regions of KT217 exhibited the highest level of homology to the aceA gene of E. coli (64% at the amino acid sequence level), which indicated that we knocked out a gene encoding an isocitrate lyase. Moreover, analysis of the isocitrate lyase activities in crude extracts revealed that P. putida KT217 contained only 1 to 5% of this enzyme activity compared to P. putida KT2442, suggesting that there was a block in the glyoxylate pathway (Table 1). Determination of the in vitro activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase revealed that the activity of mutant KT217 decreased by a factor of two to five depending on the substrate compared with wild-type strain KT2442 (Table 1). Apparently, inactivation of the aceA gene not only disrupted the glyoxylate pathway but also significantly reduced the isocitrate dehydrogenase activity.

TABLE 1.

Specific activities of isocitrate lyase and isocitrate dehydrogenase in crude extracts of P. putida KT2442 and P. putida KT217a

| Substrate(s) | Length of cultivation (h) | Sp act (nmol min−1 mg−1)b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isocitrate lyase

|

Isocitrate dehydrogenase

|

||||

| KT2442 | KT217 | KT2442 | KT217 | ||

| Gluconate (46 mM) | 24 | 43 | 2 | 569 | 182 |

| 48 | 35 | 2 | 498 | 109 | |

| Gluconate (23 mM) + heptanoate (10 mM) | 24 | 321 | 3 | 445 | 205 |

| 48 | 147 | 3 | 318 | 122 | |

Cells were cultivated in 0.1 N E2 minimal medium supplemented with gluconate or a mixture of gluconate and heptanoate. The cells were harvested at the end of the exponential phase (24 h) and in the late stationary phase (48 h).

Crude extracts were prepared and used in assays for isocitrate lyase and isocitrate dehydrogenase activities.

Accumulation of PHA in aceA knockout mutant KT217 grown on gluconate.

To investigate whether the aceA mutation affects PHA biosynthesis, we measured the growth phase-dependent PHA accumulation of P. putida KT217 and its parent strain, P. putida KT2442. Table 2 shows that during growth on gluconate the cell dry weight and amount of polymer accumulated by KT217 were significantly greater at the end of the exponential phase and in the late stationary phase than the comparable values for wild-type strain KT2442. The difference between the mean PHA accumulation in the mutant and the wild-type strain was 52%. In the late stationary phase the difference between the mean PHA accumulation in the mutant and the wild-type strain was 8%. The PHA monomer composition was relatively constant during the period studied, and 3-hydroxydecanoate was the predominant monomer in both strains (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

PHA contents and monomer compositions of P. putida KT2442 and KT217 cultivated on gluconatea

| Organism | Time (h) | Cell dry wt (g liter−1) | PHA content (g liter−1) | Maximal growth rate (h−1) | PHA content (%, wt/wt) | PHA monomer composition (mol%)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6 | C8 | C10 | C12 | C12:1 | ||||||

| KT2442 | 24 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 18.1 ± 2.1 | 0 | 12.9 | 74.1 | 7.1 | 5.9 |

| 48 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 37.9 ± 3.4 | 0.8 | 14.9 | 71.5 | 7.1 | 5.7 | ||

| KT217 | 24 | 0.7 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 27.4 ± 2.6 | 0.6 | 13.5 | 73.1 | 7.0 | 5.8 |

| 48 | 0.78 | 0.34 | 41.0 ± 4.0 | 0.9 | 15.2 | 70.9 | 7.2 | 5.8 | ||

Cells were cultivated in 0.1 N E2 minimal medium supplemented with 1% gluconate. At the end of the exponential phase (24 h) and during the late stationary phase (48 h) cells were harvested and lyophilized, and the PHA content and monomer composition were determined by gas chromatography. The values are averages based on the values obtained with triplicate samples in three independent experiments.

C6, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; C7, 3-hydroxyheptanoate; C8, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; C10, 3-hydroxydecanoate; C12, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; C12:1, 3-hydroxy-5-cis-dodecenoate.

Accumulation of PHA in aceA knockout mutant KT217 grown on mixtures of gluconate and fatty acids.

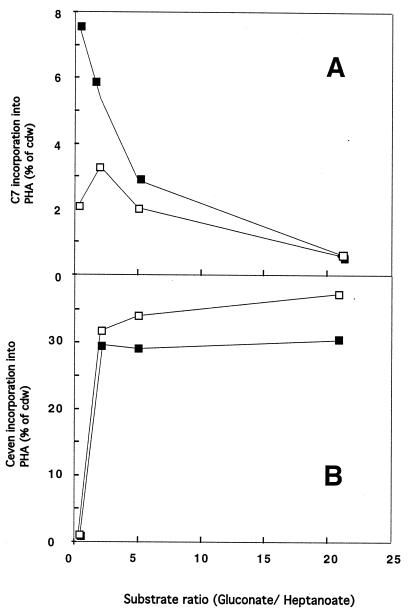

When we grew cells on mixtures of gluconate and heptanoate, PHA accumulation and PHA monomer composition depended on substrate ratios. Figure 2A shows that there was not much incorporation of heptanoate-derived monomers (C7 monomers) into PHA in the mutant and wild-type strains when cells were grown in the presence of low heptanoate concentrations (gluconate/heptanoate ratio, 21) due to heptanoate substrate limitation. As the heptanoate concentration increased (gluconate/heptanoate ratios, 5 to 2), C7 monomer incorporation into wild-type PHA increased, while the mutant incorporated less C7 monomer into PHA than the wild type incorporated due to an unknown effect. At a gluconate/heptanoate ratio of 0.3, mutant cells incorporated much smaller amounts of C7 monomers into PHA than the wild type incorporated (Fig. 2A), indicating that there were metabolic limitations because of limiting amounts of gluconate in combination with aceA gene inactivation.

FIG. 2.

Incorporation of monomers into PHA by P. putida KT2442 (■) and by aceA knockout mutant P. putida KT217 (□) grown on substrate mixtures containing gluconate and heptanoate. Cells were cultivated by using the following substrate mixtures in 0.1 N E2 minimal medium: 42 mM gluconate and 2 mM heptanoate (gluconate/heptanoate ratio, 21), 32 mM gluconate and 6 mM heptanoate (gluconate/heptanoate ratio, 5), 23 mM gluconate and 10 mM heptanoate (gluconate/heptanoate ratio, 2), and 5 mM gluconate and 18 mM heptanoate (gluconate/heptanoate ratio, 0.3). Samples were harvested after 48 h of cultivation, lyophilized, and analyzed by gas chromatography. (A) Incorporation of C7 monomers (3-hydroxyheptanoate) into mcl PHA relative to total cell dry weight (cdw). (B) Total mass of Ceven monomers (3-hydroxyhexanoate, 3-hydroxyoctanoate, 3-hydroxydecanoate, and 3-hydroxydodecanoate–3-hydroxydodecenoate) incorporated into PHA relative to total cell dry weight.

KT217 cells grown in the presence of gluconate/heptanoate ratios between 2 and 21 produced larger amounts of PHA derived from gluconate than the wild type produced (Fig. 2B); this incorporated PHA consisted of monomers with even numbers of carbon atoms (3-hydroxyhexanoate, 3-hydroxyoctanoate, 3-hydroxydecanoate, and 3-hydroxydodecanoate–3-hydroxydodecenoate [Ceven]). At a low gluconate concentration (gluconate/heptanoate ratio, 0.3), both wild-type and mutant strains incorporated small amounts of Ceven into PHA due to gluconate limitation (Fig. 2B). Our results indicate that gluconate-derived monomer incorporation into PHA was greater in mutant KT217 than in the wild type if excess gluconate was available (Fig. 2B). The increased incorporation of Ceven monomers into PHA might have been due to the aceA knockout in KT217 and was consistent with the greater accumulation of mcl PHA in KT217 than in the wild type when cells were grown on gluconate as the sole carbon source. However, when one of the substrates (gluconate or heptanoate) was present at a low concentration, small amounts of the corresponding monomers (C7 monomers for a gluconate/heptanoate ratio of 21 [Fig. 2A] and Ceven for a gluconate/heptanoate ratio of 0.3 [Fig. 2B]) were incorporated into PHA in both the mutant and the wild type.

DISCUSSION

In this study we obtained a transposon mutant of P. putida which contained increased levels of mcl PHA. Analysis of this mutant revealed that because the aceA gene was knocked out, the glyoxylate pathway was inhibited and the activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase was reduced, which resulted in increased carbon flux towards mcl PHA.

We hypothesize that the increased mcl PHA accumulation in mutant KT217 is caused by the following mechanism. Knockout of the aceA gene in KT217 results in disruption of the glyoxylate pathway. As a result of transcriptional stop elements that flank the transposon inserted in the aceA gene, transcription of the aceK gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase kinase/phosphatase is prevented. As shown previously (18), inactivation of the aceK gene can lead to reduced activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase. Due to this polar effect of aceA gene knockout, the isocitrate dehydrogenase activity in KT217 is reduced, which results in a reduction in carbon flux through the protein (34). Consequently, the flux of acetyl-CoA into the citric acid cycle is diminished, and the flux into the fatty acid synthesis pathway is increased, which leads to increased amounts of mcl PHA in KT217.

Surprisingly, the reduction in isocitrate dehydrogenase activity did not lead to reduced growth of the mutant. As a possible explanation for this result, we tested the hypothesis that the mutant excreted less secondary metabolites (e.g., acetate) than the wild type excreted. Since we could not detect significant amounts of metabolites in the culture broth supernatant of either the mutant or the wild type (data not shown), this hypothesis was not valid. We concluded that the flux of carbon through the citrate cycle in the wild type was not a limiting factor for growth. Presumably, other metabolites important for growth-relevant precursor production (e.g., acetyl-CoA), whose levels might have been increased by the aceA mutation, led to the fast growth of the mutant.

We performed a stoichiometric flux analysis of P. putida KT217 grown in a batch culture containing gluconate (Fig. 1). The model predicted that there would be increased flux into PHA if the flux through isocitrate dehydrogenase was reduced in combination with zero flux through the glyoxylate shunt. Since experimental in vivo flux data were not available, we used in vitro enzyme assays. This was a reasonable approach because isocitrate dehydrogenase is one of the rate-controlling enzymes in the citric acid cycle (34); thus, we expected a positive correlation between activity and flux through the enzyme. Indeed, we determined that the activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase was reduced by a factor of 2 to 5 in the mutant (Table 1). Thus, the stoichiometric flux analysis results corroborated our hypothesis that there is enhanced carbon flow into mcl PHAs in mutant KT217.

At high ratios of gluconate to heptanoate, the mutant accumulated larger amounts of gluconate-derived PHA than the wild type accumulated (Fig. 2B). In agreement with our pathway hypothesis, the data obtained with mixed substrates indicate that incorporation of gluconate-derived monomers into PHA was greater in mutant KT217 than in the wild type, if an excess of the carbon source gluconate was available.

In summary, in this study we found that modifying the carbon flux can help increase the amounts of bacterial products that accumulate and therefore can be a powerful tool in biotechnological strain improvement. However, since it is known that in cellular systems often no or only minor phenotypic changes occur after mutation of a single gene unless a certain set of other genes is simultaneously altered (4), a combination of the aceA knockout with other mutations might affect mcl PHA production even more. Therefore, in future work we will look more closely at generating strains with multiple mutations in order to further increase mcl PHA production in members of the genus Pseudomonas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss Federal Office for Education and Science (BBW grant 96.0348) and from the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds to S.K. and M.D., respectively.

We thank Wouter Duetz and Uwe Sauer for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann J U, Babel W. Approaches to increase the economy of the PHB production. Polym Degrad Stabil. 1998;59:183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson A J, Dawes E A. Occurence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:450–472. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.450-472.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagdasarian M, Lurz R, Ruckert B, Franklin F C H, Bagdasarian M M, Frey J, Timmis K N. Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene. 1981;16:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey J E. Lessons from metabolic engineering for functional genomics and drug discovery. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:616–618. doi: 10.1038/10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branch M A, Grace A. Optimization toolbox user's guide. Natick, Mass: A. Grace; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrom D. Polymer synthesis by microorganisms: technology and economies. Trends Biotechnol. 1987;5:246–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Smet M J, Eggink G, Witholt B, Kingma J, Wynberg H. Characterization of intracellular inclusions formed by Pseudomonas oleovorans during growth on octane. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:870–878. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.870-878.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Mansi E M T, MacKintosh C, Duncan K, Holms W H, Nimmo H G. Molecular cloning and over-expression of the glyoxylate bypass operon from Escherichia coli ML308. Biochem J. 1987;242:661–665. doi: 10.1042/bj2420661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hazenberg W M. Production of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by Pseudomonas oleovorans in two-liquid-phase media. Ph.D. thesis. Zurich, Switzerland: ETH Zurich; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hrabak O. Industrial production of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huijberts G N M, de Rijk T C, de Waard P, Eggink G. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of Pseudomonas putida fatty acid metabolic routes involved in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1995;176:1661–1666. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1661-1666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huijberts G N M, Eggink G, de Waard P, Huisman G W, Witholt B. Pseudomonas putida KT2442 cultivated on glucose accumulates poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) consisting of saturated and unsaturated monomers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:536–544. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.536-544.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huisman G W, de Leeuw O, Eggink G, Witholt B. Synthesis of poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates is a common feature of fluorescent pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1949–1954. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.1949-1954.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huisman G W, Wonink E, Meima R, Kazemier B, Terpstra P, Witholt B. Metabolism of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) by Pseudomonas oleovorans. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2191–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klinke S, Ren Q, Witholt B, Kessler B. Production of medium chain length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) from gluconate in recombinant Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:540–548. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.540-548.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lageveen R G, Huisman G W, Preusting H, Ketelaar P E F, Eggink G, Witholt B. Formation of polyester by Pseudomonas oleovorans: the effect of substrate on the formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkenoates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2924–2932. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.2924-2932.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaPorte D C, Thorsness P E, Koshland J. Compensatory phosphorylation of isocitrate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10563–10568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S Y. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;49:1–14. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960105)49:1<1::AID-BIT1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants on Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murai T, Tokushige M, Nagai J, Katsuki H. Physiological functions of NAD- and NADP-linked malic enzymes in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;43:875–881. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(71)90698-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Schaechter M. Physiology of the bacterial cell: a molecular approach. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poirier Y, Dennis D E, Klomparens K, Somerville C. Polyhydroxybutyrate, a biodegradable thermoplastic, produced in transgenic plants. Science. 1992;256:520–523. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5056.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poirier Y, Nawrath C, Somerville C. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, a family of biodegradable plastics and elastomers, in bacteria and plants. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nbt0295-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauer U, Hatzimanikatis V, Hohmann H-P, Manneberg M, van Loon A P G M, Bailey J E. Physiology and metabolic flux of wild-type and riboflavin-producing Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3687–3696. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3687-3696.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selkov E, Basmanova S, Gaasterland T, Goryanin I, Gretchkin Y, Maltsev N, Nenashev V, Overbeek R, Penyushkina E, Pronevitch L, Selkov E, Jr, Yunus I. The metabolic pathway collection from EMP: the enzymes and metabolic pathways database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:26–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selkov E, Jr, Gretchkin Y, Mikhailova N, Selkov E. MPW: the metabolic pathways database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:43–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanier R Y, Adelberg E A, Ingraham J L. General microbiology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: The Macmillan Press Ltd.; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinbüchel A. PHB and other polyhydroxyalkanoic acids. In: Rehm H-J, Reed G, editors. Biotechnology. Vol. 6. Weinheim, Germany: VCH; 1996. pp. 405–464. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timm A, Steinbüchel A. Formation of polyesters consisting of medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids from gluconate by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other fluorescent pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3360–3367. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3360-3367.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Leij F R, Witholt B. Strategies for the sustainable production of new biodegradable polyesters in plants: a review. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41(Suppl. 1):222–238. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varma A, Palsson B O. Metabolic flux balancing: basic concepts, scientific and practical use. Bio/Technology. 1996;12:994–998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Voet D, Voet J G. Biochemistry. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voordouw G, van der Vies S M, Themmen A P N. Why are two different types of pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase found in living organisms? Eur J Biochem. 1983;131:527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witholt B. Method for isolating mutants overproducing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and its precursors. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:350–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.1.350-364.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witholt B, Boekhout M, Brock M, Kingma J, Heerikhuizen H, de Leij L. An efficient and reproducible procedure for the formation of spheroplasts from variously grown Escherichia coli. Anal Biochem. 1976;74:160–170. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanisch-Perron C, Viera J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]