Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has changed attitudes of English households towards food consumption at home and when eating out. Little academic research has however examined the scope and the scale of these changes, especially in the context of foodservice provision. This mixed methods study explores the effect of Covid-19 on food consumption in English households at home and away. It reveals increased frequency and variety of cooking during lockdown as a driver of household food wastage. The study demonstrates public hesitance towards eating out post-Covid-19. Foodservice providers are expected to re-design their business settings and adopt protective and preventative measures, such as frequent cleaning and routine health checks, to encourage visitation. After the pandemic, increased preference towards consuming (more) sustainable food at home, but not when eating out, is established. These insights can aid grocery and foodservice providers in offering more tailored products and services in a post-pandemic future.

Keywords: Covid-19, Household food consumption, Grocery retail, Restaurant, Healthy eating, Food waste

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted every aspect of life across all sections of global society [1]. This disruption is associated with ‘stay at home’ orders and lengthy curfews, also known as lockdowns [2]. These lockdowns, implemented by most countries around the world, have forced people to significantly modify their routine behaviour [3]. Among others, lockdown orders have incorporated such preventative and protective measures as working/studying from home, limited socialisation and restricted travel [4].

The disruption caused by the pandemic is likely to have a lasting effect [5]. The uncertainty attributed to the spread of the virus and its mutation potential implies that various Covid-19 restrictions are likely to remain in place for a pro-longed period of time [6]. These restrictions will not necessarily be associated with strict lockdowns, but may involve temporary and regional limitations such as quarantine orders, social distancing requirements and mask wearing rules [7].

Covid-19 has significantly impacted food consumption patterns [8], and academic research aiming to understand these impacts is rapidly emerging [9]. Studies have been undertaken to comprehend the effect of the pandemic on how people buy, prepare and store food [[10], [11], [12]]. Investigations have also discussed changes in consumer preferences towards specific modes of food shopping, such as online versus offline [13], but also particular types of foodstuffs consumed in households, such as those that are plant based as opposed to meat based [14]. Studies have considered the increase in ‘grow-your-own-food’ movement [15], especially in densely populated urban areas as a means of enhancing city resilience to future disastrous events [16]. Investigations have examined the influence of lockdown orders on eating disorders [17], including changes in alcohol consumption [18]. Lastly, studies have attempted to evaluate the detrimental implications of food consumption for wastage [19] and food supply shortages [20], especially in the context of panic-buying and stockpiling caused by the introduction of lockdown orders [21].

Despite a rapidly emerging stream of academic research on the implications of the pandemic for food consumption, the analytical scope and the geographical scale of existing studies has been limited [22]. The geography of scholarly investigation has excluded some of the major global markets of food consumption, such as the UK. In the UK context, Robertson et al. [23] and Robinson et al. [24] consider eating behaviour of UK residents during national Covid-19 lockdown, but focus on health implications of behavioural changes. Despite being seminal in their geographical coverage, these studies have failed to compare consumer food preferences and food consumption patterns before, during and after lockdown. Murphy et al. [25] look into food practices of UK consumers during Covid-19 lockdown and discuss these in the context of diet quality. While advancing an understanding of food consumption patterns of UK residents, this study does not elaborate on the implications of its findings for future behavioural intentions. Similarly, Snuggs and McGregor [26] discuss food choice of UK households during Covid-19 lockdown but focus on meal planning, family food decision-making alongside food availability and accessibility, rather than food consumption patterns and the drivers behind their occurrence.

The scope of academic research on the effect of the pandemic on food consumption has primarily been concerned with eating at home [11,12,27]. Substantially less attention has been paid to the market of food consumption away from home, also known as the market of eating out, where food is provided by the foodservice sector [28]. Although research has discussed the effect of Covid-19 on risk perceptions [29], cleaning expectations [30] and visit intentions of restaurant guests [31], these studies fail to shed light on how/if the changes in food consumption at home imposed by the pandemic have affected consumer food preferences when eating out.

It is alarming that the topic of food consumption away from home in the Covid-19 related research is under-represented. The foodservice sector plays an important socio-economic role in many countries, as it represents a major source of economic revenues and employment opportunities [30]. For example, in the UK alone, prior to Covid-19, foodservices were valued at £57 billion per annum while the sector was categorised as the 4th largest national employer [32]. Concurrently, the foodservice sector, being an integral element of the global hospitality industry, has been particularly badly affected by the pandemic [33]. Lockdown orders forced most businesses to close down or substantially reduce their operations [4]. Although many foodservice providers have ceased their business only temporarily, some have chosen, given the continued uncertainty, not to reopen. The UK foodservice sector may lose up to 60% of its annual revenues due to Covid-19 [34]. In absolute terms, this may equate up to £25 billion in direct losses [28]. This outlines bleak perspectives for the foodservice sector as the lack of revenues suggests limited opportunities for re-investment as well as the inability to cover operational costs [4].

To re-build business confidence in the foodservice sector, thus facilitating its more rapid recovery in a post-Covid-19 future, a dedicated stream of scholarly research is required. This research should examine consumer expectations towards eating out in line with the determinants of customer re-visit intentions [31]. A long period of restrictions may have prompted substantial changes to what consumers expect to see in a restaurant when they eat out post-Covid-19 [29]. Foodservices need to comprehend and capitalise upon these changes in order to offer tailor-made products and services in line with consumer expectations [35]. This will not only encourage custom, but can also secure consumer loyalty.

Scholarly research should also strive to understand how the pandemic has affected consumer food preferences following a pro-longed period of cooking at home and ordering food for take-away and delivery. There is mounting evidence pinpointing that, during the lockdown periods, households have started paying more attention to such attributes of food as its healthiness, naturalness, provenance, production methods and wastage [11,36,37]. Research is necessary to investigate if this food consumption preferences and habits developed at the household level can/should be transferred to the context of eating out. Such investigations can inform foodservice providers about the food attributes valued by customers the most, thus indicating what products and services restaurants should provide after Covid-19 to encourage custom.

The aim of this exploratory study is to better understand the effect of the pandemic on food consumption at home and away in England. To this end, it will assess the extent to which Covid-19 has influenced food consumption in English households in terms of changes to their food consumption preferences and habits. The study will also examine the determinants of restaurant re-visit intentions in a post-pandemic future and investigate the role of changed food consumption preferences and habits, if any, in consumer choice of foodservice providers.

The unique contribution of this study is, thus, in that it covers both dimensions of the food consumption spectrum in households, i.e. at home and away. Given the focus of past research on the effects of Covid-19 on food consumption at home, this current study extends the scope of analysis to explore the impact of the pandemic on food consumption in the out-of-home context. Such analysis is more comprehensive and holds implications for foodservice providers as it enables a better understanding of household preferences for food consumption away from home in a post-pandemic future.

It is important to note that lockdown orders had temporarily eliminated food consumption away from home. This is because most traditional foodservice providers were closed while food was only available for take-away and delivery. This notwithstanding, for consistency reasons, the rest of the paper will refer to food consumption away from home or out-of-home food consumption when discussing the period of lockdown orders. This out-of-home food consumption will however be explicitly represented by food take-away and delivery only, as per above. The next section explains this study's research design.

2. Materials and methods

This research is exploratory by nature as little is known about how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected the patterns of food consumption in the UK, both when cooking at home and when eating out. This justifies the initial use of an inductive method based on qualitative cases because qualitative research enables a deep understanding of consumer perceptions and attitudes [38]. The results of qualitative research can then be combined with evidence from the literature review in order to design a survey questionnaire aiming at achieving better generalisation of findings [39]. Such multi-phase research design is referred to as an exploratory sequential mixed methods approach whereby a qualitative phase focused on exploration precedes a quantitative phase focused on confirmation [40]. Such complex research design, underpinned by a philosophical worldview based on pragmatism, is justified in the contexts of limited conceptualization and when study topics are characterised by limited background knowledge [41]. The results of the qualitative phase inform the questionnaire design, thus adding validity and credibility to research findings [42].

2.1. The qualitative phase – semi-structured interviews

The qualitative phase relied on semi-structured interviews for primary data collection and analysis. Semi-structured interviews represent a popular method of qualitative research given their ability to provide a detailed outlook on people's views, feelings and beliefs underwritten by their personal experiences [43]. Semi-structured interviews are well positioned to explore perceptions and attitudes of individual consumers, but also entire households, alongside their intentions and expectations [38]. Semi-structured interviews have proven effective when studying changing patterns of consumer behaviour in the Covid-19 context as a means of drawing an initial understanding of the main behavioural drivers and consequences [44].

The academic and ‘grey’ literature written on the topic of changing patterns of food consumption in light of the pandemic and available at the time of designing this study was used to develop an interview schedule. Initial themes were extracted from the literature and divided into three sections aiming to examine food consumption behaviour, at home and (if applicable) when eating out (1) before, (2) during and (3) after Covid-19 lockdown. More specifically, interview questions on how the public changed their food consumption behaviour at home during lockdown were adopted from Refs. [[45], [46], [47], [48]]. The questions on consumer behaviour and behavioural intentions towards food consumption at home and when eating out before and after Covid-19 lockdown were grounded on [47,49,50]. The interview schedule was piloted with three volunteers to achieve face and content validity. A copy of the interview schedule can be found in Supplementary material, Appendix 1.

Interview participants were initially recruited via purposive sampling, an established approach in research on food consumption behaviour [44]. As a socio-demographic profile of consumers determines their patterns of cooking at home and when eating out, theoretical sampling was later adopted to extend the sample towards different strata of society in order to develop the richness of the data [51]. The final interview sample was made up of 16 participants. These represented heads of households residing in the South-West and South-East regions of England. The sample incorporated all major socio-demographic groups of the UK population as defined by Ref. [52] (Table 1 ). The effect of data saturation was used to determine the number of interview participants [53]. The effect is normally detected within 10–30 interviews [54], and this study fits into this range.

Table 1.

Interview participants (n = 16).

| Pseudonym | Gender | Approximate age | Household structure | Employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caroline | Female | In her 40s | Partner, two children | Full-time |

| Chris | Male | In his 70s | Living alone | Retired |

| Jean | Female | In her 30s | Partner | Part-time |

| Joanna | Female | In her 50s | Partner, three children | Full-time |

| Jessica | Female | In her 40s | Partner, two children | Full-time |

| Jordan | Male | In his 40s | Partner, one child | Furloughed |

| Jupiter | Female | In her 20s | Living alone | Student |

| Kevin | Male | In his 50s | Living alone | Part-time |

| Lisa | Female | In her 20s | Partner | Unemployed |

| Lloyd | Male | In his 20s | Living alone | Student |

| Louise | Female | In her 50s | Partner, one child | Full-time |

| Matt | Male | In his 50s | Partner, one child | Furloughed |

| Ricky | Male | In his 60s | Partner | Retired |

| Sammy | Female | In her 30s | Partner | Furloughed |

| Sean | Male | In his 30s | Partner, two children | Full-time |

| Thomas | Male | In his 70s | Partner | Retired |

Interviewing took place in the first two weeks of June 2020 and, due to the lockdown restrictions, was facilitated by video communication tools, such as Skype and Zoom. Interviews lasted between 32 and 53 min; they were recorded for subsequent transcription and participants were not financially compensated for that time. The interviewing period was deliberately chosen as it was in the beginning of June 2020 when the UK government first announced its intention to relax the national Covid-19 lockdown order. It was not until the July 4, 2020, however, that this relaxation involved the reopening of foodservice establishments in the UK where customers could sit down to eat.

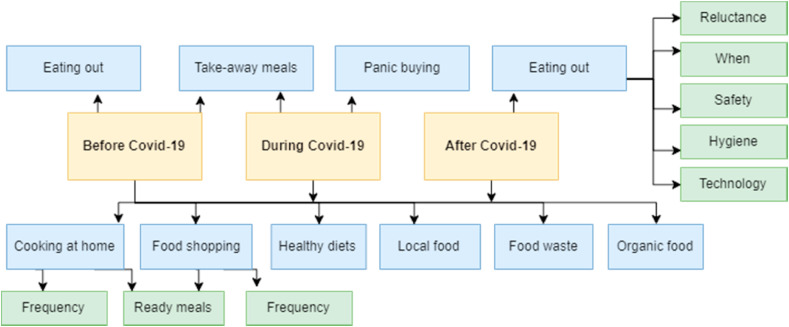

The interview transcripts were analysed thematically in line with the guidelines issued by Ref. [55]. The raw data were coded, the codes were then categorised and grouped into larger themes [56]. The coding structure was independently agreed by four members of the research team to ensure its meaningfulness and comprehensiveness [57]. Fig. 1 presents the final coding structure of the interview data.

Fig. 1.

The final coding structure of interviews. Legend: Yellow colour indicates themes. Blue colour indicates sub-themes. Green colour indicates codes.

2.2. The quantitative phase – a survey questionnaire

The survey was developed mirroring the design of the interview schedule in that the questionnaire was divided into three sections: (1) before, (2) during, and (3) after Covid-19 lockdown. In these sections, the codes developed in qualitative research became variables and the quotations were amended to develop specific survey items [58]. This resolved the issue of the initial lack of measurement scales and actual survey measures which is usually attributed to exploratory investigations [59]. The fourth section of the survey questionnaire collected socio-demographic information of the participants, such as their age, gender, education and income levels, and family status. The questionnaire incorporated multiple-choice (single answer) and Likert scaling (ranging from 1 Strongly disagree to 5 Strongly agree) questions [60]. The questionnaire was pre-tested with ten volunteers prior to its administration. A copy of the survey questionnaire can be found in Supplementary material, Appendix 2.

Due to the Covid-19 lockdown restrictions the survey was designed to be administered online using Jisc, a tailor-made online survey tool for academic research [61]. Snowball sampling was used to recruit the survey participants. This method, despite the drawback of limited representativeness, is valuable for exploratory projects whose purpose is to shed initial light on a topic in question, rather than to test complex concepts and validate robust research models [62].

The survey link was distributed in the last week of June 2020 via the ‘nextdoor.co.uk’ platform, a social network of UK households living in the same area. The survey link was sent to the neighbourhood hubs representing South-East and South-West of England. The link remained active until national lockdown order in the UK was relaxed and foodservices fully re-opened on the July 4, 2020. In total, 205 valid responses were collected and the IBM SPSS Statistics 26 package was used for their analysis.

3. Results

3.1. The qualitative phase – semi-structured interviews

3.1.1. Before Covid-19 lockdown

Before lockdown, the patterns of food consumption were very diverse. In terms of cooking at home, a third of the participants cooked often/on a regular basis, trying new recipes and experimenting with new meals. These participants were represented by families, but also retirees, i.e. households with substantial time budgets but sometimes restricted incomes. Another third of the participants did not cook often at home but relied on convenience meals purchased in supermarkets instead, especially during weekdays, primarily due to their hectic lifestyles. Such households were represented by families, but also young couples and singletons. Lastly, another third of the participants was a mixture between the other two groups whereby cooking was seen enjoyable, but depended on the situation and budget availability.

Most participants shopped for food to be consumed at home at least once a week. Many, in addition to a large weekly shop, engaged in a number of smaller, top-up, shopping journeys. When probed on wastage, the majority admitted wasting substantial amounts of food. Poor recall of the food stocks available at home, inability to consume food before it pasts its ‘use by’ date, uneaten/forgotten leftovers and significant variations in taste preferences among different household members were cited as the most common reasons for wastage.

As for eating out prior to the pandemic, variations in recorded behavioural patterns were less diverse. Most participants, regardless of their socio-demographic profile, consumed food out-of-home at least once a month, with many eating out as frequently as once a week. The youngest participants consumed food out-of-home even more often, i.e. several times per week. A very small number of participants would only eat out on special occasions. These were largely represented by retirees. When it comes to ordering food for take-away and delivery, most participants engaged in this activity once or twice a week.

As for healthy eating at home, the majority stated they tried to eat healthily when cooking. When going out, however, opinions were almost equally split. Half of the participants claimed they tried to eat healthily both at home and away, i.e. regardless of the food consumption context. Another half of the participants considered food consumption out-of-home a treat and admitted paying little attention to consuming healthy food when going out. All referred to healthy eating as regular consumption of fruits and vegetables, but also fish and unprocessed foodstuffs.

Local food was a major attraction for the participants when selecting what to buy, either for consumption at home or when eating out. The perceived (better) freshness and taste were commonly cited as the main reasons for local food's appeal. In contrast, food safety and hygiene was not a major consideration when choosing what food to eat, either at home or away. The majority trusted restaurants and grocery retailers in maintaining high levels of food safety. Only a couple of the participants claimed they routinely checked the food hygiene ratings of the restaurants they were about to visit through online review apps. The quote below provides an overview of the food consumption patterns in the studied households before Covid-19:

‘In my family, we'd try to eat healthily because of all this buzz around healthy lifestyles, I guess. We'd eat a lot of vegetables, brown bread and brown rice, for example … We're a busy family, so we often rely on convenience meals but when we're at home, I always try to make my dishes healthy. My kids don't always like this, so healthy food can sometimes become waste … As for eating out, we'd do that every second week. Again, we'd try to eat healthily when going out but this wasn't always easy. At the end, visiting a restaurant is a special thing, you know … Yes, local food is important, we'd buy it every now and then. It's fresh, it's delicious, so what's not to like? Organic is not so much though as it’s overly expensive for my family’ (Jessica)

3.1.2. During Covid-19 lockdown

During lockdown, most foodservices were closed and all participants had to cook at home. The majority found this enjoyable and considered lockdown as an opportunity to improve their cooking skills. Many admitted to having started to cook more often by preparing more complicated and sophisticated meals. Some sought inspiration by watching cooking shows on television and online. This explained why most participants did not increase the frequency of their take-away and delivery orders and some even ordered less. The suddenly decreased household incomes due to furloughs and redundancies, but also increased concerns over the safety of the food delivered, were blamed for ordering less take-away food. However, as lockdown progressed to May, and then to June 2020, many participants claimed to have tired of their own cooking and started craving restaurant food.

The issue of lockdown orders prompted stockpiling and panic buying. When probed, some claimed that they only bought enough food for their immediate household consumption while the majority confirmed that they purchased more food than needed. Many households stockpiled tinned and dried food suitable for long storage. Most participants claimed they stopped stockpiling after they witnessed grocery retailers operating ‘business as usual’ during lockdown and providing a steady supply of all major foodstuffs. In terms of the frequency of food shopping, the majority claimed that it reduced. One big, weekly, shopping trip was most popular and some participants took advantage of online grocery deliveries.

Perceptions of food waste during lockdown varied. Some participants claimed to have wasted less food. More available time and being confined to home prompted these households to repurpose surplus ingredients and reuse leftover food from meals. Some explained the reduction in food waste by the need to limit the number of shopping trips which implied eating whatever was available. Some were concerned about future financial well-being of their households and tried to cut on shopping costs, thus reducing wastage. Concurrently, many participants admitted that they produced more food waste during lockdown. This was associated with larger amounts of food purchased in supermarkets that remained un-eaten. This was also attributed to cooking more food than needed.

The patterns of healthy eating at home during lockdown varied. While many participants claimed they tried to eat healthily and consumed larger quantities of vitamins and supplements, some admitted to have cooked and eaten more than usual. This was attributed to more time available, but also boredom. Some stated that, because of mounting depression and anxiety, they ate more comfort food, such as snacks and sweets, but also drank more alcohol. Some admitted cooking more cakes and bakery items with related implications for unhealthy eating.

The appeal of local food maintained its importance during lockdown and the majority claimed to continue routinely purchasing locally produced foodstuffs. Aside from perceived benefits of freshness and taste, some engaged in this activity because of their desire to help local businesses suffering during the pandemic. Some found it easier to shop locally because shopping in large supermarkets involved queuing, which was perceived unsafe. The quote below outlines some of the food consumption patterns in the studied households during Covid-19 lockdown:

‘Oh, well, lockdown was OK in our family. We stayed at home, we cooked a lot, and we ate a lot. Even though I was furloughed, we tried not to limit ourselves. We couldn't go out to eat, so what else to spend money on?… Yes, we tried to eat as healthy as we could and we definitely added vitamins to our diets. We tried shopping locally, using online delivery, as this food was of better quality and it was safer to get it delivered … Wastage? I'd not say we wasted more food than we usually did before all this started but, yeah, some food was definitely binned as we cooked so much and so often … ’ (Matt)

3.1.3. After Covid-19 lockdown

Most participants claimed they anticipated to pursue the patterns of food consumption established during lockdown after the restrictions were lifted. Following the removal of the restrictions, they expected to spend significant time working from home due to the uncertainty attributed to the spread of the virus. The majority of the participants stated their preference towards a single, but big, shopping trip, involving increased purchase of local foodstuffs. Frequent cooking was seen as a new norm with the related impact on household food waste. There were split opinions on the trend of healthy eating: while some participants claimed they would stick to cooking healthier foodstuffs, some were uncertain about healthy eating, blaming stress and anxiety for increased usage of comfort foodstuffs.

The participants were almost equally split in their attitudes towards visiting restaurants after lockdown was lifted. While half of the participants were prepared to eat out immediately following the removal of the restrictions, another half were willing to wait, sometimes for a long time, before trying restaurants again. The elderly participants were significantly more cautious in their restaurant re-visit intentions as a result of their higher vulnerability.

To encourage visitation, it was suggested that foodservice businesses should introduce customer health checks. Most participants considered temperature checks should be compulsory. All pinpointed the need to observe social distancing rules when eating out, expecting foodservice operators to establish clear rules on the capacity of their venues, follow these rules and reinforce the social distance protocols. Dividing seating areas in restaurants using plexi-glass screens was suggested by some participants. Staff were expected to wear masks, self-service buffets were considered redundant, and disposable items (menus, cutlery, crockery and condiments) were preferred by many. Some participants were concerned with the impact of these measures on plastic waste, but all considered these necessary to prevent the spread of the virus. Technology was seen an important preventative measure. All participants opted for contactless payment and some expressed ideas of using electronic menus and smartphone apps to order food. When probed on the use of discounts to encourage visitation, the majority did not consider these important. To them, eating out in a restaurant which was Covid-19 secure was more crucial than the meal price. Only the younger participants claimed they would be attracted by price discounts justifying this by their tighter budgets. The quote below provides an overview of the anticipated food consumption patterns in the studied households in a post-Covid-19 future:

‘I'm not sure about the future as I'm somewhat worried about my job. However, I think we'll stick to the same lifestyle we've developed during lockdown. Which means cooking at home, eating as healthily as we can, with occasional treats … As for going out, I don't think I'll be rushing to a local pub immediately after lockdown is over. Even though I'm sick and tired of staying at home, it might be too risky …. I'll expect restaurants to get ready in line with what the government tells them, such as social-distancing, disinfecting and the like. However, for me personally, this may not be sufficient to give me confidence. I might wait for some time before I go out for a pint … ’ (Sean)

3.1.4. Summary of the qualitative findings

The interviews provided rich data that could be grouped into four main themes. Theme 1 relates to the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on the patterns of (more) sustainable food consumption, at home and away. These are associated with healthy eating, consumption of local foodstuffs and ingredients, less wasteful cooking, use of environmentally-friendly packaging, and consumption of foodstuffs that are characterised by more responsible practices of production, such as organic and fair trade.

Themes 2–4 relate to public expectations of foodservices in terms of the changes they should implement to their businesses in order to encourage visitation in a post-Covid-19 future. Theme 2 is about the re-design of restaurant settings for better safety, involving such measures as the abolishment of open buffets, food coverage, food provision in outdoor areas, practice of social distancing, limit on customer numbers, use of disposable items, installation of protective screens, and adoption of digital solutions to restrict human contact. Theme 3 is about the application of preventative and protective health precautions in foodservice operations, such as regular temperature checks for customers and staff and masks for employees. Theme 4 is about the application of measures of preventative hygiene in restaurants, such as deep cleaning and regular disinfection.

The interview material was used to design a survey questionnaire. In line with the guidelines by Ref. [58], the quotes from the interview transcripts were adopted to develop specific survey items. Given the lack of scholarly research on consumer intention to eat out following the pandemic (i.e. a dependent variable), the survey questionnaire aimed at shedding light on this particular topic by responding to four research hypotheses (Hs) formulated as follows: In a post-Covid-19 world:

H1

Customers expect restaurants to provide more sustainable food options;

H2

Customers expect restaurants to re-design their business settings for safety;

H3

Customers expect restaurants to look after guest health;

H4

Customers expect restaurants to invest in hygiene.

3.2. The quantitative phase – a survey questionnaire

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic profile of the survey respondents. Compared to the UK population [52], the sample was made up of a smaller number of younger respondents (6% in the sample versus 17% of the UK population), a larger number of females (71% versus 51%) and a smaller number of the employed, including furloughed (62% versus 77%). The smaller proportion of younger respondents can be explained by their limited use of the ‘nextdoor.co.uk’ platform which is purposefully designed for connecting local households. The larger share of females can be attributed to their leadership on making food decisions in their households [63]. Lastly, the smaller number of employed participants can be explained by the socio-demographic structure of resident communities in South-East and South-West of England characterised by a larger proportion of wealthy retirees [64]. This is partially confirmed by looking at the education levels of the survey respondents whereby the majority (73%) are educated to a degree level concurrently earning more than the nation's average (52%).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic profile of the survey respondents.

| Feature | Frequency (n = 205) | Share of the sample (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 | 12 | 6 |

| 26–40 | 41 | 20 | |

| 41–54 | 54 | 26 | |

| 55–64 | 51 | 25 | |

| 65+ | 47 | 23 | |

| Gender | Male | 59 | 29 |

| Female | 146 | 71 | |

| Family status | Single, never married | 41 | 20 |

| Married/Living with partner, no children | 64 | 31 | |

| Married/Living with partner, with children | 59 | 29 | |

| Divorced | 31 | 15 | |

| Widow(er) | 10 | 5 | |

| Highest education level | Secondary/High school | 51 | 25 |

| College/University | 132 | 65 | |

| Master/Doctorate | 17 | 8 | |

| Other | 5 | 2 | |

| Employment status | Full-time | 82 | 40 |

| Part-time | 28 | 14 | |

| Temporarily unemployed (excluding furlough) | 13 | 6 | |

| Furloughed | 16 | 8 | |

| Student | 9 | 4 | |

| Retired | 57 | 28 | |

| Income level | Below nation's average | 60 | 29 |

| Nation's average | 38 | 19 | |

| Above nation's average | 107 | 52 | |

3.2.1. Descriptive analysis of changing eating behaviour

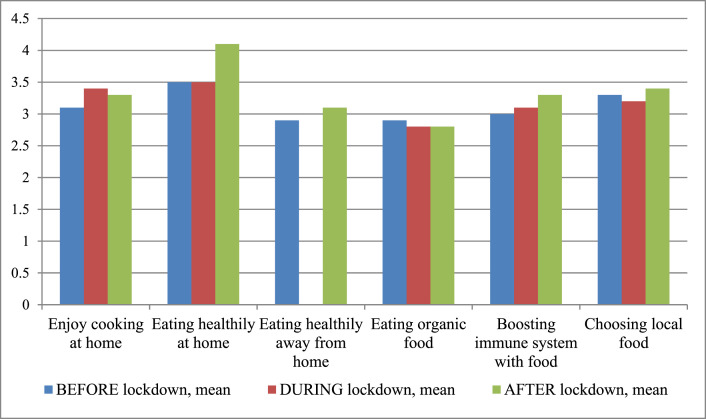

Fig. 2 outlines changes in eating behaviour of English households in light of Covid-19. It shows that a considerable share of the population has enjoyed cooking at home, during and after national lockdown. Healthy eating at home has become a norm, including increased consumption of vitamins. The ‘healthiness’ of food has increased its appeal when eating out; however, the increase is less significant than in the case of healthy cooking at home. Organic and fair trade food consumption has not changed its appeal throughout lockdown while the choice of local produce has grown, albeit insignificantly. More specifically, national lockdown has resulted in the following changes to eating behaviour: slightly reduced alcohol consumption (M = 2.91, SD = 1.377); slightly increased food stockpiling (M = 3.12, SD = 1.184); slightly increased cooking of more sophisticated and complex meals (M = 3.21, SD = 1.076); slightly increased food waste due to ordering food for take-away and delivery (M = 3.23, SD = 1.053), and significantly increased food waste due to over-cooking (M = 3.55, SD = 1.003).

Fig. 2.

Changes in eating behaviour of English households in light of Covid-19.

As for consumer intention to eat out, most households felt cautious about visiting foodservice providers after the restrictions were lifted. The survey respondents expressed their pessimism towards eating out immediately after lockdown (M = 2.28, SD = 1.249) or even when the vaccination began (M = 2.50, SD = 1.095). The majority agreed they would eat out less frequently in a post-pandemic future (M = 3.39, SD = 1.096) due to significant concern over food safety (M = 3.79, SD = 1.057).

3.2.2. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to the data collected in Section 4 Food consumption POST Covid-19 of the survey questionnaire (see Appendix 2). As a data reduction technique, EFA is capable of identifying the structure of relationships between the variables and evaluating the validity of the variable set, ultimately aiming to establish the latent factors that create commonality [65]. In EFA, in order to record the correlation relationship between the observed variable and the factor, the factor loading of 0.5 and above should be reached [66].

In EFA, principal components extraction and the oblique rotation technique were used. Oblique rotation was preferred to orthogonal rotation because it could allow for the detection of distinct, yet correlated factors [67]. As Brown argues [68], the oblique rotation technique should be preferred, especially for use in new and/or under-studied contexts, because it offers a more realistic representation of how factors can be inter-related. This is of no detriment to the quality of analysis as, if the factors are found to be uncorrelated, then the oblique rotation technique will produce a solution that is virtually identical to the one produced by the orthogonal rotation technique [68]. The use of oblique rotation was also justified by the findings of the qualitative phase of this project. In this phase the interview participants referred to a range of factors, rather than a single factor, that could prompt or inhibit their intention to eat out following the pandemic. This suggests presence of multiple factors and underlines the need to explore the relationships between them.

Following EFA, several survey items such as, for example, “Restaurants to use environmentally-friendly packaging to avoid plastic waste” and “Promotion and discount campaigns”, were removed from analysis due to low factor loadings. The final set of 21 items were gathered in four factor dimensions explaining 62.6% overall variance which is suitable for evaluation [65]. The four factor groups were named in line with the key characteristics of their composing variables, namely: “Restaurant setting”, “Sustainable eating”, “Health precautions”, and “Preventative hygiene”. The measurement of consistency and reliability returned satisfactory results (Table 3 ) as all items loaded above the threshold value of 0.3 [69].

Table 3.

The Rotated Component Matrix results.

| Component |

α |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Re-design of restaurant settings = Restaurant setting | 0.896 | ||||

| No self-service buffets | 0.757 | 0.665 | |||

| All food to be under cover | 0.718 | 0.572 | |||

| Food provided in outdoor areas | 0.643 | 0.620 | |||

| Placing tables far apart | 0.610 | 0.744 | |||

| Limit customer numbers | 0.553 | 0.734 | |||

| Disposable/wrapped items | 0.535 | 0.586 | |||

| Plexi-glass screens | 0.533 | 0.702 | |||

| Digital menus | 0.503 | 0.658 | |||

| Contactless payments | 0.501 | 0.702 | |||

| Investment in sustainability = Sustainable eating | 0.780 | ||||

| Organic and fair trade products | 0.826 | 0.572 | |||

| Cooking ingredients boosting the immune system | 0.754 | 0.626 | |||

| Reduction of wastage | 0.702 | 0.590 | |||

| Local foodstuffs/ingredients | 0.689 | 0.657 | |||

| Healthy eating at home | 0.609 | 0.630 | |||

| Healthy eating when going out | 0.581 | 0.579 | |||

| Looking after guest health = Health pre-cautions | 0.793 | ||||

| Temperature checks of customers | 0.733 | 0.660 | |||

| Temperature checks of employees | 0.710 | 0.677 | |||

| Staff wearing masks and gloves | 0.541 | 0.574 | |||

| Cleaning and disinfection = Preventative hygiene | 0.912 | ||||

| Hand sanitizers at the entrance to the venue | 0.864 | 0.860 | |||

| Hand sanitizers throughout the venue | 0.784 | 0.816 | |||

| Frequent cleaning | 0.776 | 0.803 | |||

3.2.3. Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was applied to establish correlation between the variables. The correlation coefficient (r) ranges from −1 to 1; a bigger absolute value of r indicates stronger correlation between the two variables and the variables are considered independent of each other if r = 0 [66]. The p-value (sig.) is another important attribute of the Pearson correlation test and a 95% confidence level (sig. = 0.05) is required in order to accept the relationship between the variables [65]. Table 4 presents the results of the Pearson correlation analysis. All variables are positively correlated with the r-value ranging from 0.197 to 0.683, indicating relationship, albeit not overly strong [69]. Pearson correlation analysis has indicated correlation between some independent variables, thus showcasing potential effect of multicollinearity [70].

Table 4.

The Pearson correlation test.

| Eating out intention | Restaurant setting | Sustainable eating | Health precautions | Preventative hygiene | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating out intention | Pearson correlation | 1 | ||||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | ||||||

| Restaurant setting | Pearson correlation | .197 | 1 | |||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .005 | |||||

| Sustainable eating | Pearson correlation | .005 | .361 | 1 | ||

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .024 | .000 | ||||

| Health precautions | Pearson correlation | .161 | .683 | .413 | 1 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .021 | .000 | .000 | |||

| Preventative hygiene | Pearson correlation | .025 | .670 | .385 | .525 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .042 | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||

3.2.4. Hypothesis testing

Multiple regression analysis [71] was applied to test the research hypotheses. When testing a hypothesis, the p-value (sig.) significant at less than 0.05 should be considered as it implies statistically significant influence, meaning a hypothesis is supported. The effect of “multicollinearity” should also be studied with the help of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Avoiding “multicollinearity” requires the VIF to be greater than 0.1 but less than 10.0 [72]. The contribution of the independent variables to the dependent variable should be established by checking the Beta (β) value. The variable with the highest absolute value of β exerts the largest effect on the dependent variable [71]. Table 5 presents the results of multiple regression models used in this study to test the relationships between the dependent (“Eating out intention”) and independent (“Restaurant setting”, “Sustainable eating”, “Health precautions”, and “Preventative hygiene”) variables.

Table 5.

The regression test.

| Hypothesis | VIF | Sig. | (β) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Customers expect restaurants to provide more sustainable food options | 2.231 | 0.274 | 0.083 | Not supported |

| H2: Customers expect restaurants to re-design their business settings for safety | 1.493 | 0.008 | 0.685 | Supported |

| H3: Customers expect restaurants to look after guest health | 1.001 | 0.002 | 0.099 | Supported |

| H4: Customers expect restaurants to invest in preventative hygiene | 1.261 | 0.042 | 0.391 | Supported |

Table 5 suggests that H1 : Customers expect restaurants to provide more sustainable food options should be rejected as sig. = 0.274 > 0.05 implies that Sustainable eating does not influence Eating out intention. H2 : Customers expect restaurants to re-design their business settings for safety is supported and exerts the largest effect on Eating out intention. H3 : Customers expect restaurants to look after guest health is supported although it exerts a low effect on Eating out intention. Lastly, H4 : Customers expect restaurants to invest in preventative hygiene is supported showcasing a strong effect on Eating out intention.

4. Conclusions and implications

The study has contributed to knowledge with an exploratory investigation of changes in food consumption patterns of English households as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Although some of the study's findings confirm the results of past research undertaken on this topic, some findings stand out as being noticeably different. The following discussion positions the contribution of this study in the body of current knowledge and explains the implications for theory and managerial practice.

First, this study has established that the pandemic has prompted a greater interest in healthy eating when cooking at home, which is in line with the results reported by Ref. [73] for Qatar, [74] for selected English-speaking countries, and [11] for Turkey. Concurrently, this finding contradicts the results of [75] for the Netherlands, [76] for the USA and [24] for the UK, who have all identified the negative impact of stress and anxiety prompted by Covid-19 on consumption of healthy foodstuffs at home. The variation in research outcomes indicates substantial cross-national, but also cross-societal, differences in household attitudes to healthy eating, thus highlighting the need for more in-depth investigation. A distinctive contribution of the current study is in that it has attempted to shed light on future intentions to eat healthily at home, confirming that this trend may persist in England after the pandemic is over. This holds important implications for English grocery retail operators that should aim at capitalizing on this consumption trend by updating their current lines of healthy products, but also offering new product lines containing foodstuffs fortified with vitamins and minerals.

Second, the current study has established a slight growth in English households' interest in consuming local food. This is in line with the findings reported by Ref. [11] for Turkey and [20] for Spain, thus showcasing the increasing importance of the ‘local’ appeal in future food consumption patterns of households around the world. Grocery retail operators should harness this appeal by collaborating with local farmers to offer a greater variety of locally grown foodstuffs. Local farmers, in England and beyond, should also take advantage of this food consumption trend by delivering local food directly to households. This is viable given that many households have increased their food shopping online [77] which provides scope for farmers to link to consumers directly, eliminating the need for a ‘middle man’ and optimizing costs.

Third, the study has shown that organic food has not increased its appeal in English households during Covid-19. This contradicts the results reported in Ref. [78] for China. This can be partially explained by increased price sensitivity of consumers in England whereby furloughs and employment insecurity may have prompted households to limit their food budgets. Given that organic foodstuffs are premium priced, it is then logical to assume that these are not prioritised in a time of crisis despite their benefits for personal health and the environment.

Fourth, this study has revealed increased food wastage in English households during lockdown, predominantly attributed to over-cooking as a spillover effect of working/studying at home. This finding contradicts the results of [79] for Romania, [77] for Tunisia, and [80] for Italy, but aligns with the results of [21] reported for the USA and India. This showcases the role of various socio-demographic, but also psychological, political and potentially cultural, factors in shaping food consumption patterns alongside subsequent wastage that require a better understanding. Future research is also necessary to evaluate how households in various countries behave in a time of crisis and consequently comprehend the implications of this behaviour for the dynamics of household food waste.

From the management perspective, the study has enhanced an understanding of the factors that English consumers will prioritise in a post-Covid-19 future when deciding on where to eat out. Despite the increased appeal of such ‘sustainability’ attributes of food as its healthiness, provenance and, to a lesser extent, (more responsible) methods of production when cooking at home, these attributes do not sustain in the context of out-of-home food consumption. This study shows that customers may not necessarily prioritise sustainability when eating out in the pandemic's aftermath. This can be attributed to the fact that eating out, due to its exclusivity, will be viewed as a treat because of the pro-longed periods of cooking at home. When treating themselves, customers will be unlikely to pay attention to the sustainability elements of foodservice provision.

The above presents an important challenge for foodservice providers. On the one hand, they will need to effectively respond to consumer demands to ensure quick custom return and, thus, gradual reinstatement of revenue flows. On the other hand, foodservice providers play a crucial role in enhancing sustainability awareness of their guests [81]. In a post-Covid-19 future, the sector of foodservice, in England and beyond, will need to find a balance between short-term revenue generation and its long-term commitment to sustainability. The empirical evidence provided in this current study, but also in research by Refs. [11,27,77], highlighting increased consumer awareness of sustainable food when cooking at home should encourage foodservice providers to consider embracing sustainability in their business models. This is to capitalise on changed consumer attitudes to food consumption, thus signalling that the (more sustainable) patterns of cooking at home can also be fulfilled in the out-of-home environment. This may become feasible as the pandemic retreats and the eating out routines go back to normal, thus diminishing the element of exclusivity which is likely to dominate in the immediate Covid-19's aftermath.

Another important managerial contribution of this study rests in the outline of factors which English consumers consider vital to facilitate their return to restaurants. These factors are represented by (sorted in the order of significance): the re-design of restaurant settings in line with safety requirements; adoption of measures of preventative hygiene; and routine application of health checks and health precautions. Foodservice businesses must invest in these measures to ensure their short-term survival, but also long-term business viability, given that the pandemic's effects are likely to remain in the global economy and society for a prolonged period of time. As discussed earlier, consumer expectations of foodservice providers to look after their health when eating out are linked to the importance of food healthiness when cooking at home. Health considerations will be a critical pre-requisite for customers to visit restaurants in the future and foodservice providers must recognise this and change their business models and operational settings accordingly.

As any research project, this study has a number of limitations. The non-representativeness of its quantitative data posits the largest drawback even though it is justified by the exploratory nature of this investigation. The survey measures developed and effectively trialled in the current project can be utilized to develop a large-scale, population-representative, study in England, but also beyond. Another potential limitation is associated with the timeframe of conducting this research. In June 2020, due to the novelty of the pandemic and because of the lack of its scientific understanding, English households may have feared the worst. This could have affected their perceptions and attitudes towards food consumption. A replication of this study in 2021, i.e. in the later stages of Covid-19, may provide different, but equally significant, insights. Studying perceptions and attitudes of people who have and have not contracted the virus can also offer an innovative outlook.

Future research directions, aside from those outlined earlier, should be concerned with an in-depth investigation of a particular food attribute (i.e. healthy eating or local food) and its impact on household consumption preferences and habits conducted across the different strata of society, in England and beyond. This particularly concerns how households understand the notion of ‘sustainable food’ and what effect, if any, the pandemic may have had on the household interpretation of the related food attributes. The perspective of foodservice providers on changes to the patterns of food consumption in households should also be examined. In particular, the scope of the industry response to customer expectations in terms of business safety and restaurant product offer should be sought. Lastly, the viewpoints of policy-makers on how to sustain positive changes in food consumption patterns of households (for example, healthy eating) and how to diminish the negative effects (for instance, food waste) should be explored.

Author statement

Viachaslau Filimonau Conceptualization, Data analysis, Data curation, Writing – final draft. Le Hong Vi Conceptualization, Data collection, Data analysis, Writing – initial draft. Sean Beer Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – final draft. Vladimir A. Ermolaev Conceptualization, Dana analysis, Writing – final draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors hereby declare no conflict of interest

Biographies

Viachaslau Filimonau is Principal Lecturer in Hospitality Management in the Faculty of Management at Bournemouth University, UK. His research interests include the challenges of food (in)security and environmental management in tourism and hospitality operations. He is particularly interested in the problem of food waste and its management across all segments of the global food supply chain.

Le Hong Vi is a Postgraduate Student at Bournemouth University, UK, with research interest in food consumption and hospitality management.

Sean Beer is a Senior Lecturer in Agriculture in the Bournemouth University Business School, UK. His research interests include issues relating to sustainability and Food and Drink supply chains, particularly in relation to local food production and consumption.

Vladimir A. Ermolaev is Professor of the Department of Commodity Science and Expertise in Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Russia. His research interests include the challenges of food (in)security. He is particularly interested in the problem of food waste, dairy production, drying technology, and food cold storage technology.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101125.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Khan S.A.R., Razzaq A., Yu Z., Shah A., Sharif A., Janjua L. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences; 2021. Disruption in food supply chain and undernourishment challenges: an empirical study in the context of asian countries. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcaccia G., D'Agostino V., Zotti A., Cozzi B. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 on the Italian agri-food sector: an analysis of the quarter of pandemic lockdown and clues for a socio-economic and territorial restart. Sustainability. 2020;12(14):5651. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodeur A., Clark A.E., Fleche S., Powdthavee N. COVID-19, lockdowns and well-being: evidence from google trends. J Publ Econ. 2021;193:104346. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filimonau V., Derqui B., Matute J. The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers. Int J Hospit Manag. 2020;91:102659. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torales J., O'Higgins M., Castaldelli-Maia J., Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 2020;66(4):317–320. doi: 10.1177/0020764020915212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scudellari M. How the pandemic might play out in 2021 and beyond. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02278-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02278-5 5 August 2020. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han E., Mei M., Turk E., Sridhar D., Leung G., Shibuya K., et al. Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet. 2020;396(10261):1525–1534. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eftimov T., Popovski G., Petkovic M., Seljak B.K., Kocev D. COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020;104(10):268–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chenarides L., Grebitus C., Lusk J.L., Printezis I. Food consumption behavior during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Agribusiness. 2020;37(1):44–81. doi: 10.1002/agr.21679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faour-Klinbeil D., Osaili T.M., Al-Nabulsi A.A., Jemni M., Todd E.C.D. An on-line survey of the behavioral changes in Lebanon, Jordan and Tunisia during the COVID-19 pandemic related to food shopping, food handling, and hygienic practices. Food Contr. 2021;125:107934. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Güney O.I., Sangün L. How COVID-19 affects individuals' food consumption behaviour: a consumer survey on attitudes and habits in Turkey. Br Food J. 2021 doi: 10.1108/BFJ-10-2020-0949. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulighe G., Lupia F. Food first: COVID-19 outbreak and cities lockdown a booster for a wider vision on urban agriculture. Sustainability. 2020;12:5012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X., Shi X., Guo H., Liu Y. To buy or not buy food online: the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the adoption of e-commerce in China. PloS One. 2020;15(8):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancello R., Soranna D., Zambra, Zambon A., Invitti C. Determinants of the lifestyle changes during COVID-19 pandemic in the residents of Northern Italy. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:6287. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sofo A., Sofo A. Converting home spaces into food gardens at the time of Covid-19 quarantine: all the benefits of plants in this difficult and unprecedented period. Hum Ecol. 2020;48:131–139. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sardeshpande M., Rupprecht C., Russo A. Edible urban commons for resilient neighbourhoods in light of the pandemic. Cities. 2021;109:103031. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branley-Bell D., Talbot C.V. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK lockdown on individuals with experience of eating disorders. J Eating Disord. 2020;8:44. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00319-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehm J., Kilian C., Ferreira-Borges C., Jernigan D., Monteiro M., Parry C.D.H., et al. Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19: implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(4):301–304. doi: 10.1111/dar.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodgers R.F., Lombardo C., Cerolini S., Franko D.L., Omori M., Linardon J., et al. “Waste not and stay at home” evidence of decreased food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic from the U.S. and Italy. Appetite. 2021;160:105110. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldaco R., Hoehn D., Laso J., Margallo M., Ruiz-Salmon J., Cristobal J., et al. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci Total Environ. 2020;742:140524. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brizi A., Biraglia A. “Do I have enough food?” How need for cognitive closure and gender impact stockpiling and food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national study in India and the United States of America. Pers Indiv Differ. 2021;168:110396. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kecinski M., Messer K.D., McFadden B.R., Malone T. Environmental and regulatory concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the pandemic food and stigma survey. Environ Resour Econ. 2020;76(4):1139–1148. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00438-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson M., Duffy F., Newman E., Bravo C.P., Ates H.H., Sharpe H. Exploring changes in body image, eating and exercise during the COVID-19 lockdown: a UK survey. Appetite. 2021;159:105062. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson E., Boyland E., Crisholm A., Harrold J., Maloney N.G., Marty L., et al. Obesity, eating behavior and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: a study of UK adults. Appetite. 2021;156:104853. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy B., Benson T., McCloat A., Mooney E., Elliott C., Dean M., Lavelle F. Changes in consumers' food practices during the COVID-19 lockdown, implications for diet quality and the food system: a cross-continental comparison. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):20. doi: 10.3390/nu13010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snuggs S., McGregor S. Food & meal decision making in lockdown: how and who has Covid-19 affected? Food Qual Prefer. 2021;89:104145. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amicarelli V., Bux C. Food waste in Italian households during the Covid-19 pandemic: a self-reporting approach. Food Secur. 2021;13:25–37. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01121-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panzone L.A., Larcom S., She P.W. Estimating the impact of the first COVID-19 lockdown on UK food retailers and the restaurant sector. Global Food Secur. 2021;28:100495. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrd K., Her E., Fan A., Almanza B., Liu Y., Leitch S. Restaurants and COVID-19: what are consumers' risk perceptions about restaurant food and its packaging during the pandemic? Int J Hospit Manag. 2021;94:102821. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim K., Bonn M.A., Cho M. Clean safety message framing as survival strategies for small independent restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hospit Tourism Manag. 2021;46:423–431. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hakim M.P., Zanetta L.D., da Cunha D.T. Should I stay, or should I go? Consumers' perceived risk and intention to visit restaurants during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Food Res Int. 2021;141:110152. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.FWD-Federation of Wholesale Distributors Foodservice customers. 2021. https://www.fwd.co.uk/wholesale-distribution/the-customers/foodservice-customers/ Available from:

- 33.Song H.J., Yeon J., Lee S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the U.S. restaurant industry. Int J Hospit Manag. 2021;92:102702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mintel . Mintel Academic; London: 2020. British lifestyles 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonfanti A., Vigolo V., Yfantidou G. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on customer experience design: the hotel managers' perspective. Int J Hospit Manag. 2021;94:102871. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marty L., de Lauzon-Guillain B., Labesse M., Nicklaus S. Food choice motives and the nutritional quality of diet during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Appetite. 2021;157:105005. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scacchi A., Catozzi D., Boietti E., Bert F., Siliquini R. COVID-19 lockdown and self-perceived changes of food choice, waste, impulse buying and their determinants in Italy: QuarantEat, a cross-sectional study. Foods. 2021;10(2):306. doi: 10.3390/foods10020306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chrysochou P. In: Consumer perception of product risks and benefits. Emilien G., Weitkunat R., Lüdicke F., editors. Springer; Cham: 2017. Consumer behavior research methods; pp. 409–428. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fetters M.D., Curry L.A., Creswell J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6):2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creswell J.W., Plano Clark V.L. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2018. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tashakkori A., Teddlie C. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1989. Mixed methodology: combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cameron R. A sequential mixed model research design: design, analytical and display issues. Int J Mult Res Approaches. 2009;3(2):140–152. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones I., Brown L., Holloway I. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. Qualitative research in sport and physical activity. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naeem M. Do social media platforms develop consumer panic buying during the fear of Covid-19 pandemic. J Retailing Consum Serv. 2021;58:102226. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bracale R., Vaccaro C.M. Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to Covid-19. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(9):1423–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mattioli A.V., Sciomer S., Cocchi C., Maffei S., Gallina S. Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;30(9) doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020. 1409-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez-Pérez C., Molina-Montes E., Verardo V., Artacho R., García-Villanova B., Guerra-Hernández E.J., Ruíz-López M.D. Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients. 2020;12:1730. doi: 10.3390/nu12061730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheth J. Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: will the old habits return or die? J Bus Res. 2020;117:280–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.CGA . CGA; Manchester: 2020. Eating and drinking out in the post-Covid-19 market : a case study from China. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodell J.W. COVID-19 and finance: agendas for future research. Finance Res Lett. 2020;35:101512. doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conlon C., Timonen V., Elliott-O’Dare C., O'Keeffe S., Foley G. Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(6):947–959. doi: 10.1177/1049732319899139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ONS-Office for National Statistics CT0570_2011 Census-Sex by age by IMD2004 by ethnic group. 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/adhocs/005378ct05702011censussexbyagebyimd2004byethnicgroup Available from:

- 53.Fusch P.I., Ness L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2015;20(9):1408–1416. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marshall B., Cardon P., Poddar A., Fontenot R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: a review of qualitative interviews in IS research. J Comput Inf Syst. 2013;54(1):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Downe-Wamboldt B. Content analysis: method, applications, and issues. Health Care Women Int. 1992;13(3):313–321. doi: 10.1080/07399339209516006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guest G., MacQueen K.M., Namey E.E. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. Applied thematic analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morgan D.L. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual Health Res. 1998;8(3):362–376. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greene J.C., Caracelli V.J., Graham W.F. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Pol Anal. 1989;11(3):255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar R. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. Research methodology : a step-by-step guide for beginners. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sekaran U., Bougie R. Wiley; 2013. Research methods for business : a skill-building approach. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghauri P.N., Grønhaug K. Financial Times; Prentice Hall: 2005. Research methods in business studies : a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Belch M., Willis L. Family decision at the turn of the century: has the changing structure of households impacted the family decision-making process? J Consum Behav. 2002;2(2):111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pickford J. Financial Times; 2019. Where Britain's wealthiest live. 10 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salkind N.J. SAGE; Thousand Oaks: 2010. Encyclopedia of research design. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hair J.F., Black B., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. Pearson Prentice Hall; New Jersey: 2010. Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cleveland M., Kalamas M., Laroche M. Shades of green: linking environmental locus of control and pro-environmental behaviors. J Consum Market. 2005;22(4):198–212. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown T.A. Guilford Press; Guilford: 2006. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jabnoun N., Hassan Al‐Tamimi H.A. Measuring perceived service quality at UAE commercial banks. Int J Qual Reliab Manag. 2003;20(4):458–472. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alin A. Multicollinearity. Wiley Interdiscipl Rev: Comput Stat. 2010;2(3):370–374. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaffer J.P. Multiple hypothesis testing. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46(1):561–584. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pallant J. McGraw-Hill; 2013. SPSS survival manual : a step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ben Hassen T., El Bilali H., Allahyary M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on food behavior and consumption in Qatar. Sustainability. 2021;12(17):6973. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flanagan E.W., Beyl R.A., Fearnbach S.N., Altazan A.D., Martin C.K., Redman L.M. The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity. 2021;29(2):438–445. doi: 10.1002/oby.23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Poelman M.P., Gillebaart M., Schlinkert C., Dijkstra S.C., Derksen E., Mensink F., et al. Eating behavior and food purchases during the COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study among adults in The Netherlands. Appetite. 2021;157:105002. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Powell P.K., Lawler S., Durham J., Cullerton K. The food choices of US university students during COVID-19. Appetite. 2021;161:105130. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jribi S., Ismail H.B., Doggui D., Debbabi H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: what impacts on household food wastage? Environ Dev Sustain. 2020;22:3939–3955. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00740-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qi X., Yu H., Ploeger A. Exploring influential factors including COVID-19 on green food purchase intentions and the intention–behaviour gap: a qualitative study among consumers in a Chinese context. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(19):7106. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burlea-Schiopoiu A., Ogarca R.F., Barbu C.M., Craciun L., Baloi I.C., Mihai L.S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food waste behaviour of young people. J Clean Prod. 2021;294:126333. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Principato L., Secondi L., Cicatiello C., Mattia G. Caring more about food: the unexpected positive effect of the Covid-19 lockdown on household food management and waste. Soc Econ Plann Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2020.100953. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Filimonau V., Krivcova M. Restaurant menu design and more responsible consumer food choice: an exploratory study of managerial perceptions. J Clean Prod. 2017;143:516–527. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.