Abstract

A limited number of Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium strains possess a hydrogen uptake (Hup) system that recycles the hydrogen released from the nitrogen fixation process in legume nodules. To extend this ability to rhizobia that nodulate agronomically important crops, we investigated factors that affect the expression of a cosmid-borne Hup system from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, Rhizobium etli, Mesorhizobium loti, and Sinorhizobium meliloti Hup− strains. After cosmid pAL618 carrying the entire hup system of strain UPM791 was introduced, all recipient strains acquired the ability to oxidize H2 in symbioses with their hosts, although the levels of hydrogenase activity were found to be strain and species dependent. The levels of hydrogenase activity were correlated with the levels of nickel-dependent processing of the hydrogenase structural polypeptides and with transcription of structural genes. Expression of the NifA-dependent hupSL promoter varied depending on the genetic background, while the hyp operon, which is controlled by the FnrN transcriptional regulator, was expressed at similar levels in all recipient strains. With the exception of the R. etli-bean symbiosis, the availability of nickel to bacteroids strongly affected hydrogenase processing and activity in the systems tested. Our results indicate that efficient transcriptional activation by heterologous regulators and processing of the hydrogenase as a function of the availability of nickel to the bacteroid are relevant factors that affect hydrogenase expression in heterologous rhizobia.

Hydrogen production due to nitrogenase activity is a source of inefficiency in Rhizobium-legume symbioses. Certain rhizobial strains synthesize a hydrogen uptake (Hup) system that recycles the hydrogen that evolves during the N2 fixation process. This ability to utilize H2 reduces energy losses and has been shown to enhance legume productivity (11, 12).

In symbiosis with peas, Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 induces a [NiFe] hydrogenase whose genetic determinants have been isolated in cosmid pAL618 (24). A sequence analysis of the 20-kb DNA region cloned in this cosmid revealed the presence of a gene cluster (hupSLCDEFGHIJK hypABFCDEX) required for the Hup+ phenotype (19, 25, 33, 34, 36). The hupSL genes code for the hydrogenase structural polypeptides which exhibit high levels of sequence similarity with hydrogenase structural subunits from other bacteria (for reviews see references 14 and 46). The remaining hup and hyp genes are necessary for synthesis of an active hydrogenase, although the specific functions of most of these genes have not been determined yet. Unlike the Bradyrhizobium japonicum system, the R. leguminosarum Hup system is induced only during symbiosis through regulators involved in the nitrogen fixation process (41). Expression of the hupSL genes is observed only in pea bacteroids and has been shown to be controlled by the nitrogenase regulatory protein NifA (4). In contrast, hyp genes are induced under microaerobic conditions as well as under symbiotic conditions by the transcriptional activator FnrN (17, 18). The R. leguminosarum UPM791 hydrogenase is posttranslationally activated by a nickel-dependent processing system that requires hup and hyp gene products (6). During this process, the immature small (HupS) and large (HupL) structural polypeptides are converted into active forms in the presence of nickel. Processing of the large subunit has been studied in detail with Escherichia coli hydrogenase 3. In this system, which is highly homologous to the R. leguminosarum system, the precursor HycE large subunit is converted into its mature form by removal of a C-terminal 32-amino-acid peptide (38). This proteolytic processing step is carried out by a specific protease encoded by the hycI gene (39), which is homologous to the hupD gene of R. leguminosarum, and depends on the presence of nickel. Consistent with this requirement, adding nickel to an R. leguminosarum UPM791-pea symbiosis system results in a significant increase in hydrogenase activity, indicating that the availability of nickel to plants can be a limiting factor for hydrogenase activity in symbioses (6).

The ability to utilize H2 is a desirable characteristic for generating more productive and efficient rhizobial inoculants (12, 28). Unfortunately, this phenotype has been found only in a few Rhizobium and Bradyrhizobium strains (10). Thus, extension of this ability to other rhizobia has obvious biotechnological interest and has been the aim of several previous studies (1, 23, 29, 45). In our laboratory we have tried to generate genetically engineered Rhizobium strains with high energy efficiency by introducing the hydrogen oxidation system from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791. In order to incorporate the ability to recycle H2 into rhizobia that nodulate agronomically important crops, we studied factors that affect expression of the hydrogenase system in different rhizobial backgrounds. In this study we analyzed the expression of cosmid-borne hup genes from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae, Rhizobium etli, Mesorhizobium loti, and Sinorhizobium meliloti Hup− strains. Our results indicate that both hup gene transcription by heterologous regulators and the availability of nickel to plants are critical factors that affect hydrogenase activity in heterologous hosts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The rhizobial strains used in this study were R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 (26), UML2 (25, 40), and PRE (5, 27), R. etli CFN42 (25, 32), S. meliloti 102F34 (8), and M. loti Y3 and U226 (29). Cosmid pAL618 is a pLAFR1 (Tcr) derivative harboring the hydrogenase gene cluster from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 (24). Cosmids pHL55, pHL14, and pHL12 are pAL618 derivatives carrying lacZ fusions due to insertion of a Tn3HoHo1 transposon (31) (Fig. 1). These cosmids were introduced into Rhizobium strains by triparental mating by using pRK2073 as a helper plasmid and the procedure of Ditta et al. (9). Transconjugants were selected on Rhizobium minimal medium (30) supplemented with tetracycline (5 μg · ml−1). E. coli HB101 used for matings was grown in Luria-Bertani medium. Rhizobium strains were grown in TY medium (2) or in yeast mannitol medium (YMB) (47). To determine cosmid stability in nodules, bacteroid suspensions were serially diluted in YMB and plated onto YMB agar. One hundred colonies were streaked onto YMB agar with or without tetracycline, and the frequency of tetracycline-resistant colonies was calculated.

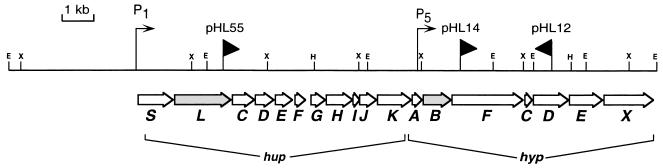

FIG. 1.

Physical and genetic map of the hydrogenase gene cluster from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 cloned in cosmid pAL618. The horizontal arrows below the pAL618 restriction map indicate the locations and orientations of the hup and hyp genes. The shaded arrows indicate genes whose encoded products were detected by an immunoblot analysis in this study. The thin arrows indicate promoters that control symbiotic expression of hydrogenase structural genes (P1) (19) or microaerobic expression of the hypBFCDEX operon (P5) (18). The vertical lines with black triangles indicate the sites of insertion and the orientations of the lacZ gene in pAL618-derived fusion constructs pHL55, pHL14, and pHL12 (31). Restriction sites: E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; X, XhoI.

Plant tests and enzyme assays.

Pea (Pisum sativum L. cv. Frisson), bean (Phaseolus vulgaris cv. Negro Jamapa), alfalfa (Medicago sativa L. ecotype Aragón), and birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) plants were inoculated with R. leguminosarum, R. etli, S. meliloti, and M. loti strains, respectively. After sterilization in sodium hypochlorite, pea and bean seeds were pregerminated on 1% agar plates, whereas alfalfa and birdsfoot trefoil seeds were directly sown. Seeds or seedlings were inoculated with bacterial cultures and plants were grown under bacteriologically controlled conditions as previously described by Leyva et al. (24). The nitrogen-free nutrient solution used was supplemented with 170 μM Ni2+ chloride salts 10 days after bacteria were inoculated (6). R. leguminosarum, R. etli, S. meliloti, and M. loti bacteroids were prepared from nodules of 24-day-old pea, bean, alfalfa, and birdsfoot trefoil plants, respectively, and H2 uptake hydrogenase activity was analyzed by the amperometric method (40). H2 evolution in intact nodules was determined by chromatography by using a Konik model KNK-2000 gas chromatograph equipped with a Molecular Sieve 5A column and a thermal conductivity detector. β-Galactosidase activities in bacteroid cells were measured as previously described (31).

Immunological detection of Hup and Hyp proteins.

HupL and HypB proteins in bacteroid extracts were detected immunologically by using R. leguminosarum HypB-specific antisera (35) and B. japonicum HupL antisera (a gift from R. J. Maier). Immunoblot assays were performed as described by Brito et al. (6). Briefly, crude extracts from bacteroids were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gels and were transferred onto Immobilon-P membrane filters (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The filters were then incubated with a 1:2,000 dilution of the HupL antiserum or a 1:1,500 dilution of the HypB antiserum. Blots were developed by using a secondary goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-alkaline phosphatase conjugate antibody and a chromogenic substrate (bromochloroindolyl phosphate-nitro blue tetrazolium) as recommended by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

RESULTS

Hydrogenase activity induced by hup genes from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae in heterologous rhizobial backgrounds.

To identify factors that affect hydrogenase activity in heterologous backgrounds, hup genetic determinants from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 cloned in cosmid pAL618 (24) (Fig. 1) were introduced into different Hup− rhizobia. To do this, R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UML2 and PRE, S. meliloti 102F34, R. etli CFN42, and M. loti Y3 and U226 were used as recipient Hup− strains. Transconjugant strains carrying cosmid pAL618 were used to inoculate the corresponding host plants, which were grown in a standard nutrient solution, and the ability of bacteroids to utilize H2 was determined (Table 1). The data show that introduction of cosmid pAL618 resulted in hydrogenase activity in bacteroids of all of the Hup− strains tested except S. meliloti 102F34. Nevertheless, the activities varied widely among species and strains. The hydrogen uptake values for bacteroids of R. leguminosarum PRE(pAL618), R. etli CFN42(pAL618), and M. loti U226(pAL618) were similar to the hydrogen uptake values obtained for UPM791(pAL618), whereas the levels of hydrogenase activity of R. leguminosarum UML2(pAL618) and M. loti Y3(pAL618) bacteroids were lower. In all of these cases, the activity increased when methylene blue was used as an artificial acceptor of electrons from hydrogenase. In contrast, very low levels of hydrogen oxidation when either oxygen or methylene blue was the electron acceptor were observed in S. meliloti 102F34(pAL618) cultures. High levels of bacteroid hydrogenase activity resulted in nodules that produced no detectable H2 (strains derived from R. leguminosarum PRE, R. etli CFN42, and M. loti U226), whereas R. leguminosarum UML2(pAL618) and M. loti Y3(pAL618) recycled 80 and 86% of the H2 evolved by the nitrogenase, respectively. In contrast, S. meliloti 102F34(pAL618) recycled less than 10% of the H2 produced in nodules. Cosmid stability was determined in bacteroid suspensions obtained from plants grown in the standard nutrient solution (Table 1). The percentages of stability differed slightly depending on the recipient background. However, the differences were not correlated with variations in hydrogenase activity. In particular, similar levels of cosmid maintenance were observed in strains that exhibited high levels (UPM791 and PRE) and low levels (UML2 and 102F34).

TABLE 1.

Hydrogenase activities induced by cosmid pAL618 in bacteroids of different Rhizobium strains as a function of the addition of nickel to the plant nutrient solution

| Recipient strain | Hydrogenase activity (μmol of H2 · h−1 · mg of protein−1)a

|

Cosmid stability (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Ni2+ added

|

170 μM Ni2+ added

|

||||

| O2 | Methylene blue | O2 | Methylene blue | ||

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 | 4.50 ± 0.25 | 7.50 ± 1.15 | 16.90 ± 0.67 | 37.90 ± 6.82 | 82 |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UML2 | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 2.82 ± 0.12 | 2.20 ± 0.14 | 3.50 ± 0.26 | 80 |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae PRE | 5.52 ± 1.04 | 14.10 ± 2.55 | 9.79 ± 1.29 | 51.05 ± 7.54 | 65 |

| M. loti Y3 | 2.15 ± 0.35 | 3.55 ± 0.18 | 3.01 ± 0.17 | 6.45 ± 0.85 | 53 |

| M. loti U226 | 3.17 ± 0.42 | 7.32 ± 0.65 | 9.56 ± 1.05 | 24.76 ± 2.66 | 72 |

| R. etli CFN42 | 5.00 ± 0.36 | 12.30 ± 0.60 | 5.30 ± 0.41 | 13.50 ± 0.83 | 70 |

| S. meliloti 102F34 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.2 | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 1.32 ± 0.16 | 64 |

Hydrogenase activities were determined by using oxygen and methylene blue as electron acceptors and are averages ± standard errors based on at least two determinations.

It has been shown that adding nickel to a plant nutrient solution increases the hydrogenase activity of R. leguminosarum UPM791 pea bacteroids (6). Accordingly, we studied whether the nickel content of the nutrient solution had a stimulating effect on the symbiotic hydrogen-oxidizing ability induced by pAL618 in the different recipient strains. To do this, we measured the hydrogenase activity induced in bacteroids obtained from plants grown in a nutrient solution supplemented with 170 μM Ni2+ (Table 1). In bacteroids of R. leguminosarum UPM791(pAL618), R. leguminosarum PRE(pAL618), and M. loti U226(pAL618), increases in hydrogen uptake were observed when nickel was added. With R. leguminosarum UML2(pAL618) and M. loti Y3(pAL618) bacteroids hydrogenase activity increased slightly when nickel was added, whereas no significant difference was detected with R. etli CFN42(pAL618). In the case of S. meliloti 102F34(pAL618), adding nickel resulted in an increase in hydrogenase activity in the presence of oxygen or methylene blue, although the values were still very low.

Analysis of Ni-dependent HupL processing.

In most of the strains studied, hydrogenase activity increased when nickel was added. This prompted us to study the effect of adding nickel on the HupL status of the bacteroids that had been previously tested to determine their hydrogenase activities. To analyze this effect, we performed Western blot experiments with HupL antibodies raised against the large subunit of the B. japonicum hydrogenase.

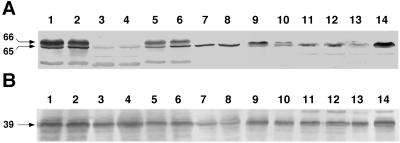

Immunodetection of HupL showed that the overall amount of fast-migrating, processed subunits was correlated with the level of hydrogenase activity observed in bacteroids. However, the amount and status of HupL depended on the rhizobial background (Fig. 2A). R. leguminosarum UPM791(pAL618) contained the largest amount of HupL protein, which was detected in two immunoreactive bands at ca. 66 and 65 kDa (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). A nonspecific band at ca. 50 kDa was also produced. Adding nickel resulted in partial conversion of the slowly migrating inactive band (66 kDa) into the fast-moving active form (65 kDa). This pattern was also observed in bacteroids of R. leguminosarum PRE(pAL618) (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 6), indicating that hydrogenase structural proteins are subject to similar levels of synthesis and processing in these two backgrounds. In contrast, a small amount of HupL protein was detected in bacteroids of R. leguminosarum UML2(pAL618) (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4). In this strain, the weak band of processed protein observed under no-nickel-added conditions became slightly stronger when nickel was added. The increase correlated with the increase in hydrogenase activity described above (Table 1). This result indicates that nickel deficiency limits hydrogen uptake in the UML2(pAL618)-pea symbiosis, as was the case with R. leguminosarum bv. viciae strains UPM791 and PRE. However, the small amount of HupL detected in bacteroids of UML2(pAL618) suggests that the level of synthesis of the hydrogenase subunits is the main factor that limits hydrogenase activity in this symbiosis.

FIG. 2.

Immunological detection of HupL and HypB proteins in heterologous rhizobia carrying hup cosmid pAL618. Immunoreactive bands were detected by immunoblotting after bacteroid crude cell extracts were resolved in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Blots were developed with antisera raised against HupL (A) or HypB (B). The bacteroids used to prepare cell extracts were obtained from nodules of plants grown in standard nutrient solutions (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13) or in solutions supplemented with 170 μM NiCl2 (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14). The numbers on the left indicate the molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of the different bands, as deduced from comparisons with standard molecular weight markers. The strains used were R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791(pAL618) (lanes 1 and 2), UML2(pAL618) (lanes 3 and 4), and PRE(pAL618) (lanes 5 and 6); R. etli CFN42(pAL618) (lanes 7 and 8); S. meliloti 102F34(pAL618) (lanes 9 and 10); and M. loti Y3(pAL618) (lanes 11 and 12) and U226(pAL618) (lanes 13 and 14).

In S. meliloti 102F34(pAL618) alfalfa bacteroids, most of the HupL polypeptide was in the unprocessed, slowly moving form (Fig. 2A, lane 9). This protein was converted into the processed form when nickel was added, although unprocessed protein was still present (Fig. 2A, lane 10). The small amount of HupL protein synthesized in this strain and the presence of the unprocessed form under high-nickel conditions suggest that the nickel added to the plants might not have been available to alfalfa bacteroids for incorporation into the hydrogenase.

With bean bacteroids of R. etli CFN42(pAL618), only the fast-migrating form of HupL was detected, and the intensity of the immunoreactive band did not change when nickel was added (Fig. 2A, lanes 7 and 8). The lack of changes in the amount of processed HupL when nickel was added is consistent with the lack of a response of hydrogenase activity to nickel in this strain (Table 1). These results indicate that HupL is completely processed in this host, even at nickel concentrations that limit hydrogenase activity in other symbioses. This suggests that an optimal ratio of hydrogenase synthesis to processing occurs in this background. M. loti Y3(pAL618) and U226(pAL618) bacteroids from L. corniculatus also produced a single band corresponding to the mature form of HupL, but in contrast to the situation with CFN42(pAL618), the intensity of this immunoreactive band was greater with bacteroids from plants exposed to high levels of nickel (Fig. 2A, lanes 11 through 14). The Ni-dependent appearance of processed protein may indicate that processing stabilizes HupL, whose unprocessed form is presumably degraded in the absence of nickel.

It has been shown previously that HupL processing depends on the presence of the entire hyp operon (6, 21). In order to investigate whether the lack of processing in some heterologous backgrounds (like S. meliloti 102F34) was due to a lack of synthesis of Hyp proteins, we examined the presence of HypB in bacteroid cells by using R. leguminosarum HypB-specific antisera (Fig. 2B). Blots developed with these antisera showed that similar levels of HypB were expressed in all bacterial hosts and that adding nickel did not alter the intensity of the corresponding immunoreactive band. The overall conclusion of this experiment is that the HypB protein and hence probably the rest of the proteins encoded by the hyp operon are efficiently synthesized in the Rhizobium strains tested and do not limit hydrogenase activity in nodule bacteroids.

Analysis of hup and hyp gene expression.

We studied the observed correlation between the amount of HupL protein detected and hupL gene expression in certain strains. To do this, we analyzed transcriptional activation of the hupL-lacZ fusion borne in cosmid pHL55 (Fig. 1) in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791, UML2, and PRE, R. etli CFN42, and S. meliloti 102F34. We also examined hyp gene expression by using cosmid pHL14, which carries a hypF-lacZ fusion. As a negative control, we included cosmid pHL12, which harbors a Tn3HoHo1 transposon inserted in the opposite orientation into the hypD gene (Fig. 1). Levels of β-galactosidase activity associated with the gene fusions were measured in bacteroid suspensions of the different transconjugant strains (Table 2). In these bacteroids, the stabilities of pAL618 derivative fusion constructs were similar to the stabilities observed for pAL618 (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

β-Galactosidase activities induced by hup-lacZ and hyp-lacZ fusions in bacteroids of different rhizobial strainsa

| Strain | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pHL55 → (hupL::lacZ) | pHL14 → (hypF::lacZ) | pHL12 ← (hypD::lacZ) | |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 | 520 ± 16 | 1,700 ± 174 | 110 ± 16 |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UML2 | 140 ± 24 | 2,000 ± 180 | 114 ± 34 |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae PRE | 623 ± 33 | 1,491 ± 18 | 120 ± 26 |

| R. etli CFN42 | 125 ± 20 | 1,850 ± 110 | 59 ± 13 |

| S. meliloti 102F34 | 120 ± 25 | 540 ± 97 | 20 ± 4 |

Bacteroids were obtained from plants grown in a standard nutrient solution.

β-Galactosidase activities are averages ± standard errors based on at least two determinations.

Our determination of the level of β-galactosidase activity associated with the hupL-lacZ fusion (pHL55 construct) revealed that hup genes were actively transcribed in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 and PRE (Table 2). In contrast, weak induction of the hupL-lacZ fusion was detected in R. leguminosarum UML2. These results are consistent with the total amount of HupL protein visualized in the immunological assays (Fig. 2A). In bacteroids of R. etli CFN42 and S. meliloti 102F34, the levels of hupL gene expression were intermediate between the levels observed in strains UPM791 and UML2 (Table 2), which is also consistent with the amounts of HupL detected in bacteroids of CFN42(pAL618) and 102F34(pAL618). These data show that efficient transcriptional activation of hup genes by heterologous regulators is a limiting factor for the ability to oxidize H2 in certain rhizobial backgrounds.

In contrast to hup genes, hyp genes were efficiently expressed in bacteroids from all symbioses tested, as shown by the β-galactosidase activity associated with the hyp-lacZ fusion pHL14 (Table 2). This result is consistent with the similar levels of HypB protein observed in bacteroids, as determined by immunoblot experiments (Fig. 2B).

DISCUSSION

In this study we identified factors that affect the hydrogen-recycling ability induced by cosmid-borne hup genes from R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 transferred into heterologous Hup− Rhizobium strains. Generation of H2-oxidizing rhizobial strains by introduction of plasmid-borne hup genes from B. japonicum and R. leguminosarum bv. viciae into other rhizobia has been described previously (1, 22, 23, 25, 29, 42, 45). In these studies, hydrogenase activities depended on the bacterial background, as well as on the legume host cultivar. However, no further efforts were made to explain the observed differences in hydrogenase activity. This prompted us to study in more detail factors that affect hydrogenase activity in heterologous hosts. Our data from immunological assays and our analysis of hup gene expression highlighted two main factors that affect the efficient expression of the hydrogenase system in heterologous rhizobial hosts.

The first factor that controls hydrogenase activity is efficient transcription of hydrogenase structural genes in heterologous rhizobia. In contrast to the active expression of hup genes in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791 and PRE, extremely low levels of hup induction were detected in R. leguminosarum UML2, and only reduced levels were observed in R. etli CFN42 and S. meliloti 102F34. In R. leguminosarum UPM791, hup gene expression is activated by NifA through noncanonical NifA upstream activating sequences (4). Thus, the low level of hup transcription observed in certain backgrounds might be explained by an inefficient recognition of these nonconsensus NifA binding sequences. However, no structural or functional differences in NifA would be expected among strains of the same Rhizobium species, such as R. leguminosarum bv. viciae UML2, UPM791, and PRE (37). Alternatively, differences in hup gene expression could be due to differences in the availability of NifA in the symbioses. There is evidence that the pool of NifA in the cell is strictly regulated in certain rhizobial backgrounds (13). In S. meliloti, overexpression of NifA negatively affects nitrogen fixation (7). In addition, introduction of traits encoded by NifA-regulated genes (nodulation efficiency and transport of dicarboxylic acids) improves symbiosis performance in the presence of additional copies of the nifA gene (3, 43), suggesting that the level of NifA protein can be a limiting factor for gene expression in S. meliloti. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the levels of NifA available for activation of additional, less canonical promoters could be very low in bacteroids in some symbiotic systems. In contrast, hyp genes are actively transcribed in all of the backgrounds tested. The latter result indicates that the P5 promoter, which is regulated by FnrN in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae (17, 18), is efficiently activated by Fnr type regulators present in different rhizobia, as shown previously for S. meliloti FixK (18, 31).

The second aspect relevant for expression of hydrogenase activity in heterologous backgrounds is the availability of nickel. Previous studies revealed that the nickel content of a plant nutrient solution limits hydrogenase processing and activity in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae pea bacteroids (6). Here, we show that the hydrogenase activities of pAL618-containing bacteroids of R. leguminosarum bv. viciae PRE and UML2, S. meliloti 102F34, and M. loti Y3 and U226 increased when nickel was added. We also demonstrated that hydrogenase activities in Rhizobium-legume symbioses can be correlated with the amount of processed HupL protein detected in bacteroids and that the observed Ni-dependent increases in hydrogen oxidation in these symbiotic systems are a consequence of Ni-dependent HupL processing. Additional evidence suggested that an adequate amount of nickel is required for stability of Hup gene products in some backgrounds, such the M. loti background. In this host, only the processed form of HupL was detected, and the intensity of the immunoreactive band increased when nickel was added. Nickel is not involved in regulation of hup gene expression in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae bacteroids (6). In addition, nickel apparently had no effect on cosmid stability, since the HypB levels were not affected when nickel was added. Consequently, the increase in the amount of the processed HupL protein in M. loti bacteroids from plants grown in the presence of high nickel concentrations was probably due to stabilization of HupL by nickel-dependent processing. On the basis of all of these data we concluded that nickel availability may limit hydrogenase activity in many different Rhizobium-legume symbioses.

It is interesting that the R. etli-Phaseolus system appears to be an exception to the general behavior of Rhizobium-legume systems with regard to the effect of nickel on hydrogenase activity. With this symbiosis, adding nickel to the plant nutrient solution did not alter the level of the processed hydrogenase large subunit and, consequently, did not affect hydrogenase activity. Furthermore, the immature HupL subunit was completely processed at nickel concentrations that limit hydrogenase activity in other symbioses. The availability of nickel to bacteroids depends on the nickel transport capacity of the different rhizobial strains and on the ability of the host plant to provide nickel to the bacteroids. Although the amount of information concerning nickel transport and metabolism in symbiotic bacteria is increasing (15, 16, 44), little is known about this process in plants (20). The lack of information hampers designing strategies which optimize providing nickel to bacteroids. On the other hand, soils with high nickel contents are rare in agricultural systems. For these reasons, a desirable approach for generating Rhizobium inoculants that express the ability to utilize H2 would be to select for symbiotic combinations that exhibit optimized synthesis and processing of the hydrogenase enzyme at low nickel concentrations, as might be the case for the R. etli-bean symbiosis. The immunological test used in this study can be a useful tool for identifying symbiotic partners that exhibit such an optimal ratio.

The analysis described here was aimed at identifying factors that affect efficient expression of the hydrogenase system in different Rhizobium hosts in order to extend the ability to oxidize H2 to Hup− rhizobial strains. Our results suggest that both hup gene expression and the availability of nickel to bacteroids can be limiting in certain legume-Rhizobium systems and that adequate attention must be paid to these factors when new inoculants with high hydrogen-recycling capacity are designed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. J. Maier for the generous gift of HupL-specific antisera.

This work was supported by grant PB95-0232 from DGICYT (Spain) and by grant CT960027 (IMPACT 2) from the EU Biotech Programme (both to T.R.-A.), as well as by grant BIO96-0503 from CICYT (Spain) to J.I. B.B. was the recipient of a Contrato de Incorporación de Doctores y Tecnólogos from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura (Spain).

REFERENCES

- 1.Behki R M, Selvaraj G, Iyer V N. Derivatives of Rhizobium meliloti strains carrying a plasmid of Rhizobium leguminosarum specifying hydrogen uptake and pea-specific symbiotic functions. Arch Microbiol. 1985;140:352–357. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beringer J. R factor transfer in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Gen Microbiol. 1974;84:188–198. doi: 10.1099/00221287-84-1-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosworth A H, Williams M K, Albrecht K A, Kwiatkowsky R, Beynon J, Hankinson T R, Ronson C W, Cannon F, Wacek T J, Triplett E W. Alfalfa yield response to inoculation with recombinant strains of Rhizobium meliloti with an extra copy of dctABD and/or modified nifA expression. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3815–3832. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3815-3832.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brito B, Martínez M, Fernández D, Rey L, Cabrera E, Palacios J M, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Hydrogenase genes from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae are controlled by the nitrogen fixation regulatory protein NifA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6019–6024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brito B, Palacios J, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T, Yang W, Bisseling T, Schmitt H, Kerl V, Bauer T, Kokotek W, Lotz W. Temporal and spatial co-expression of hydrogenase and nitrogenase genes from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae in pea (Pisum sativum L.) root nodules. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brito B, Palacios J M, Hidalgo E, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Nickel availability to pea (Pisum sativum L.) plants limits hydrogenase activity of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae bacteroids by affecting the processing of the hydrogenase structural subunits. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5297–5303. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5297-5303.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon F, Beynon J, Hankinson T, Kwiatkowski R, Legocki R P, Ratcliffe H, Ronson C, Szeto W, Williams M. Increasing biological nitrogen fixation by genetic manipulation. In: Bothe H, de Bruijn F J, Newton W E, editors. Nitrogen fixation: hundred years after. Stuttgart, Germany: Gustav Fischer; 1988. pp. 735–740. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbin D, Ditta G, Helinski D R. Clustering of nitrogen fixation (nif) genes in Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:221–228. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.221-228.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski D R. Broad host range DNA cloning system for Gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon R O D. Hydrogenase in legume root nodule bacteroids: occurrence and properties. Arch Microbiol. 1972;85:193–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00408844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans H J, Hanus F J, Haugland R A, Cantrell M A, Xu L S, Russell F J, Lambert G R, Harker A R. Hydrogen recycling in nodules affects nitrogen fixation and growth of soybeans. In: Shibles R, editor. Proceedings of the III World Soybean Research Conference. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press; 1985. pp. 935–942. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans H J, Russell S A, Hanus F J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. The importance of hydrogen recycling in nitrogen fixation by legumes. In: Summerfield R J, editor. World crops: cool season food legumes. Boston, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988. pp. 777–791. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer H M. Genetic regulation of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:352–386. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.352-386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrich B, Schwartz E. Molecular biology of hydrogen utilization in aerobic chemolithotrophs. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:351–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu C, Javedan S, Moshiri F, Maier R. Bacterial genes involved in incorporation of nickel into hydrogenase enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5099–5103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu C, Maier R J. Competitive inhibition of an energy-dependent nickel transport system by divalent cations in Bradyrhizobium japonicum JH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3511–3516. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3511-3516.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutiérrez D, Hernando Y, Palacios J M, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. FnrN controls symbiotic nitrogen fixation and hydrogenase activities in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae UPM791. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5264–5270. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5264-5270.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernando Y, Palacios J M, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. The hypBFCDE operon from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae is expressed from an Fnr-type promoter that escapes mutagenesis of the fnrN gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5661–5669. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5661-5669.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hidalgo E, Palacios J M, Murillo J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of four additional genes of the hydrogenase structural operon from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4130–4139. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.4130-4139.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holland M A, Polacco J C. Urease-null and hydrogenase-null phenotypes of a phylloplane bacterium revealed altered nickel metabolism in two soybean mutants. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:942–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.3.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobi A, Rossmann R, Böck A. The hyp operon gene products are required for the maturation of catalytically active hydrogenase isoenzymes in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 1992;158:444–451. doi: 10.1007/BF00276307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kent A D, Wojtasiak M L, Robleto E A, Triplett E W. A transposable partitioning locus used to stabilize plasmid-borne hydrogen oxidation and trifolitoxin production genes in a Sinorhizobium strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1657–1662. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1657-1662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambert G R, Harker A R, Cantrell M A, Hanus F J, Russell S A, Haugland R A, Evans H J. Symbiotic expression of cosmid-borne Bradyrhizobium japonicum hydrogenase genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:422–428. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.2.422-428.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyva A, Palacios J M, Mozo T, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Cloning and characterization of hydrogen uptake genes from Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4929–4934. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.4929-4934.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leyva A, Palacios J M, Murillo J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Genetic organization of the hydrogen uptake (hup) cluster from Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1647–1655. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1647-1655.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leyva A, Palacios J M, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Conserved plasmid hydrogen uptake (hup)-specific sequences within Hup+Rhizobium leguminosarum strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2539–2543. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2539-2543.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lie T A, Soe-Agnie I E, Muller G J L, Goedkan D. Environmental control of nitrogen fixation: limitation to and flexibility of the legume-Rhizobium system. In: Broughton W J, John C K, Rakara J C, Lim B, editors. Proceedings of the Symposium on Soil Microbiology and Plant Nutrition. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: University of Kuala Lumpur; 1979. pp. 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier R J, Triplett E W. Towards more productive, efficient and competitive nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacteria. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1996;15:191–234. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monza J, Díaz P, Borsani O, Ruiz-Argüeso T, Palacios J M. Evaluation and improvement of the energy efficiency of nitrogen fixation in Lotus corniculatus nodules induced by Rhizobium loti strains indigenous to Uruguay. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;13:565–571. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Gara F, Shanmugam K T. Regulation of nitrogen fixation by rhizobia: export of fixed nitrogen as NH4+ Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;437:313–321. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(76)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palacios J M, Murillo J, Leyva A, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Differential expression of hydrogen uptake (hup genes) in vegetative and symbiotic cells of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:363–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00259401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinto C, de la Vega H, Flores M, Fernández L, Ballado T, Soberón G, Palacios R. Nitrogen fixation genes are reiterated in Rhizobium phaseoli. Nature (London) 1982;299:724–726. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rey L, Fernández D, Brito B, Hernando Y, Palacios J M, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. The hydrogenase gene cluster of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae contains an additional gene, hypX, encoding a protein with sequence similarity to the N10-formyl tetrahydrofolate-dependent enzyme family and required for nickel-dependent hydrogenase processing and activity. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:237–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02173769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rey L, Hidalgo E, Palacios J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Nucleotide sequence and organization of an H2-uptake gene cluster from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae containing a rubredoxin-like gene and four additional open reading frames. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:998–1002. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90886-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rey L, Imperial J, Palacios J M, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Purification of Rhizobium leguminosarum HypB: a nickel-binding protein required for hydrogenase synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6066–6073. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6066-6073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rey L, Murillo J, Hernando Y, Hidalgo E, Cabrera E, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. Molecular analysis of a microaerobically induced operon required for hydrogenase synthesis in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:471–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roelvink P W, Hontelez J G J, van Kammen A, van den Bos R C. Nucleotide sequence of the regulatory nifA gene from Rhizobium leguminosarum PRE: transcriptional control sites and expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1441–1447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossmann R, Sauter M, Lottspeich F, Böck A. Maturation of the large subunit (HycE) of Escherichia coli hydrogenase 3 requires nickel incorporation followed by C-terminal processing at Arg537. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossmann R, Maier T, Lottspeich F, Böck A. Characterization of a protease from Escherichia coli involved in hydrogenase maturation. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:545–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruiz-Argüeso T, Hanus F J, Evans H J. Hydrogen production and uptake by pea nodules as affected by strains of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Arch Microbiol. 1978;116:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruiz-Argueso, T., J. M. Palacios, and J. Imperial. Regulation of the hydrogenase system in R. leguminosarum. Plant Soil, in press.

- 42.Sajid G M, Campbell W F. Symbiotic activity in pigeon pea inoculated with wild-type Hup−, Hup+, and transconjugant Hup+Rhizobium. Trop Agric. 1994;71:182–187. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanjuan J, Olivares J. Multicopy plasmids carrying the Klebsiella pneumoniae nifA gene enhance Rhizobium meliloti nodulation competitiveness on alfalfa. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;4:365–369. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stults L W, Mallick S, Maier R J. Nickel uptake in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1398–1402. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1398-1402.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasudev S, Lodha M L, Sreekumar K R. Imparting hydrogen-recycling capability to Cicer-rhizobial strains by plasmid pIJ1008 transfer. Curr Sci. 1991;60:600–603. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vignais P M, Toussaint B. Molecular biology of membrane-bound H2-uptake hydrogenases. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00248887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vincent J M. A manual for the practical study of root-nodule bacteria. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications, Ltd.; 1970. [Google Scholar]