Abstract

Objectives

Vaccinating healthcare workers (HCWs) against COVID-19 has been a public health priority since rollout began in late 2020. Promoting COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs would benefit from identifying modifiable behavioural determinants. We sought to identify and categorize studies looking at COVID-19 vaccination acceptance to identify modifiable factors to increase uptake in HCWs.

Study design

Rapid evidence review.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and Cochrane databases until May 2021 and conducted a grey literature search to identify cross-sectional, cohort, and qualitative studies. Key barriers to, and enablers of, vaccine acceptance were categorized using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), a comprehensive theoretical framework comprising 14 behavioural domains.

Results

From 19,591 records, 74 studies were included. Almost two-thirds of responding HCWs were willing to accept a COVID-19 vaccine (median = 64%, interquartile range = 50–78%). Twenty key barriers and enablers were identified and categorized into eight TDF domains. The most frequently identified barriers to COVID-19 vaccination were as follows: concerns about vaccine safety, efficacy, and speed of development (TDF domain: Beliefs about consequences); individuals in certain HCW roles (Social/professional role and identity); and mistrust in state/public health response to COVID-19 (Social influences). Routinely being vaccinated for seasonal influenza (Reinforcement), concerns about contracting COVID-19 (Beliefs about consequences) and working directly with COVID-19 patients (Social/professional role and identity) were key enablers of COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs.

Discussion

Our review identified eight (of a possible 14) behavioural determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among HCWs that, if targeted, could help design tailored vaccination messaging, policy, campaigns, and programs to support HCWs vaccination uptake.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccination, Healthcare workers, Healthcare professionals, Rapid review, Barriers and enablers, Theoretical Domains Framework

Introduction

Since late 2020, breakthroughs in vaccine development have been crucial for curbing the COVID-19 pandemic which as of February 2022 has caused an estimated 5.7 million deaths globally.1 As vaccine programs continue to be rolled out, albeit at markedly differing paces worldwide,2 addressing COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and uptake among high-priority groups such as healthcare workers (HCWs) remains an urgent public health challenge. High uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among HCWs, along with the wider public, is needed to achieve maximal effectiveness, especially in light of emerging variants of concern.3

There is a growing literature on factors linked to vaccination hesitancy, acceptance, and uptake in HCWs, spanning multiple methods and approaches and in particular data collected using surveys and interviews with HCWs worldwide. This breadth poses a challenge to decision-makers faced with developing supports to encourage greater uptake. As such, there is an opportunity to bring consistency across the literature using behavioural frameworks that can enable better links to be made between barriers and strategies best suited to address them in HCW vaccination campaigns worldwide.

Framing COVID-19 vaccination uptake as a behaviour enables drawing upon decades of theory-informed empirical research aimed at understanding factors that affect what people think, feel, decide, and ultimately do. Comprehensive frameworks, such as the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF),4, 5, 6 synthesise these factors into 14 behavioural domains (Knowledge; Skills; Social/professional role and identity; Beliefs about capabilities; Optimism; Beliefs about consequences; Reinforcement; Intentions; Goals; Memory, attention, and decision processes; Environmental context and resources; Social influences; Emotion; and Behavioural regulation) that represent over 30 theories of behaviour and behaviour change reflecting key, modifiable factors that influence behaviour. An advantage of synthesising the existing literature with such frameworks is that it is possible to: a) assess which type of barrier to getting vaccinated is appearing most and least in the literature; b) assess whether there are under-considered domains that are deserving of greater attention given their known relationship with decisions and action generally; and c) enable linkage to tools that suggest particular behaviour change techniques best suited to address particular domains.7 Using this behavioural lens, we conducted a rapid evidence review of factors linked to COVID-19 vaccination acceptance in HCWs and use the TDF to bring consistency across the literature.

Objectives

To identify key behavioural determinants of COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs and use a comprehensive theoretical framework to bring consistency across the literature.

Methods

Study design

Rapid reviews are a form of evidence synthesis that use abbreviated systematic review methods to answer pressing health questions in short time frames, often for localized decision-making purposes. Although not a replacement for a full systematic review, rapid reviews still follow the principles of robust evidence synthesis including comprehensive searches, rigorous extraction, and transparent reporting.8 , 9 This type of methodology has been extensively used during the COVID-19 pandemic given the need for time-sensitive evidence synthesis to inform public health policy and practice.10

Data sources

We conducted ongoing searches for primary studies in MEDLINE, Cochrane Register of Clinical Trials, and the Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register in accordance with a registered protocol (PROSPERO registration: CRD42021253533). The search strategy can be found in Appendix 1. We included peer-reviewed papers, preprints, and published reports of primary studies meeting our eligibility criteria below. The latest search of these databases was done on May 24, 2021. In addition, we manually searched four publicly available reports which focused on COVID-19 vaccination in Canada as part of a grey literature search.11, 12, 13, 14

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included studies investigating COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs (e.g., doctors, nurses, pharmacists, hospital staff; role could be self-identified) and excluded studies where general public samples only were used. Self-report measures of COVID-19 vaccination willingness/intention/hesitancy/acceptance (referred to as ‘vaccination acceptance’ hereafter) were included and vaccination acceptance had to relate to self-vaccination rather than HCWs vaccinating others as part of their clinical role. We excluded studies that only measured COVID-19 vaccination knowledge. We included studies conducted since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (January 2020 onwards) and we included cross-sectional, cohort and qualitative studies.

Data extraction

Citations from all searches were de-duplicated and entered into Abstrackr software, a free online screening tool that uses machine learning capabilities to predict the likelihood of relevance of each citation (http://abstrackr.cebm.brown.edu/). Two researchers conducted independent screening at level 1 (title and abstract) and level 2 (full-text) with discrepancies resolved via consensus meetings. Data extraction was undertaken using a standardised data extraction form which captured data on study characteristics and reported determinants of COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination acceptance were coded to key barriers and enablers and mapped onto the TDF. A barrier/enabler was considered ‘key’ if it had been coded in ≥3 separate studies. Given the rapid review methodology, no study quality assessment was done.

Results

Study characteristics

From 19,591 records, a total of 74 studies met our inclusion criteria15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88 (see Appendix 2 for PRISMA flow diagram). Appendix 3 provides an overview of each study. Fifty-five studies were published peer-reviewed papers, 16 were preprints, and two were published reports. Fifty-nine of 74 studies collected data in the period since COVID-19 vaccine approval (November 2020 onwards). Seventy-one of 74 studies used cross-sectional survey designs, two were qualitative studies,21 , 36 and one was a cohort study.43 Twenty-three of 74 studies were conducted exclusively in North America. Fifty-one studies were conducted outside of North America: Europe (France,33 , 63, Germany;20 , 42 , 59 Greece and Cyprus,68 Greece,52 , 62 Italy,25 , 26 , 50 Poland,45 , 76 Slovenia,65 Turkey34 , 41 , 46 , 84 , 87 and UK15 , 83); Asia (China,31 , 73 , 81 , 86 Hong Kong,49 , 82 India,75 Pakistan,69 Taiwan47 and Vietnam38); South America (Colombia18); Central America (Mexico22); Africa (Cameroon,30 Democratic Republic of Congo,60 Egypt,29 , 37 , 71 Ghana16 and Uganda40); Middle East (Iraq,17 Israel,27 , 88 Lebanon,85 Palestine54 , 67 and Saudi Arabia19 , 66 , 77) and multiple countries.45 , 64 , 80

Fifty-one of 74 studies recruited general HCWs samples of which seven recruited mixed samples that included HCWs as well as participants from the general public and/or patients.17 , 35 , 43 , 47 , 56 , 65 , 87 Twenty-three of 74 studies recruited specific professions/specialities: medical students,40 , 51 , 71 skilled nursing facility staff,36 dental professionals/students,55 , 88 paediatricians,34 intensive care staff,42 physicians,18 nurses,67 non-physicians,24 , 32 nursing home/assisted living staff,79 continuing care workers,70 pharmacy professionals,61 personal support workers,78 nurses/trainee nurses,49 , 53 , 64 , 82 ophthalmology residents,45 emergency medical services personnel,59 doctor and nurses.73

Rates of COVID-19 acceptance among HCWs

Almost two-thirds of responding HCWs were willing to accept a COVID-19 vaccine (number of studies (k) = 72; median = 64%; interquartile range (IQR) = 50–78%). Among North American studies, the median average of responding HCWs willing to accept a COVID-19 vaccine was also 64% (k = 21; IQR = 56–80%). In rest-of-the-world studies, 62% of responding HCWs were willing to accept a vaccine for COVID-19 (k = 51, IQR = 49–77%). Among studies conducted in the period since COVID-19 vaccine approval (November 2020 onwards), 64% (k = 57; IQR = 53–80%) of responding HCWs were willing to accept a COVID-19 vaccine.

Behavioural determinants of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among HCWs

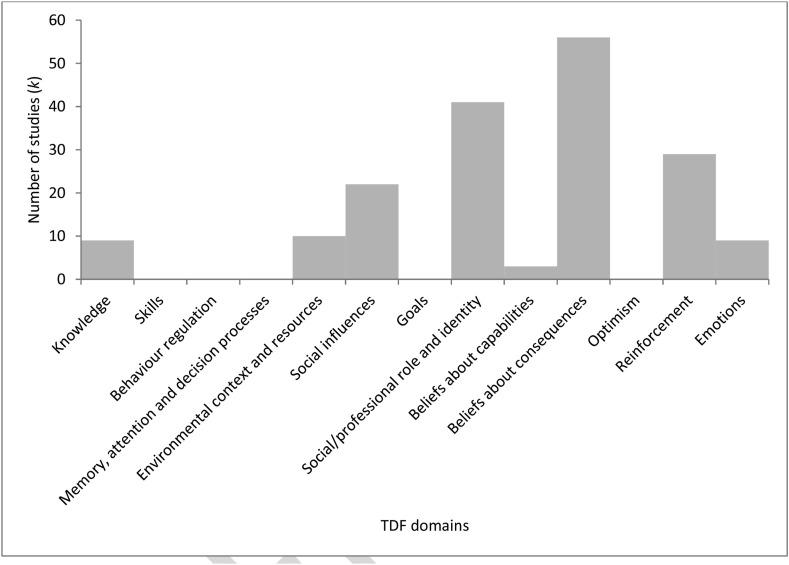

Eight (of a possible 14) TDF domains appear to be important determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among HCWs (Fig. 1 ): Knowledge [k = 9]; Environmental context and resources [k = 10], Social influences [k = 22]); and Beliefs about consequences [k = 56], Beliefs about capabilities [k = 3], Social/professional role and identity [k = 41], Reinforcement [k = 29], and Emotion [k = 9]) (Table 1 ). Compared to data focusing on COVID-19 vaccination in the general public,89 similar barriers to and enablers of COVID-19 vaccination in HCWs were identified. Domains that do not seem to be important determinants of COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs include: Skills, Behavioural regulation, Memory, attention and decision processes, Goals, and Optimism. Figs. 2 and 3 depict the 20 most frequent key barriers and enablers (coded in ≥3 studies), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) factors within 74 studies of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among healthcare workers (HCWs). Notes. TDF domain Intention not listed, given that study vaccination acceptance outcome is synonymous with this construct.

Table 1.

Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among healthcare workers (HCWs).

| TDF domain | Definition | Barriers | Enablers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | What do HCWs know & how does that influencewhat they do? Do they have the procedural knowledge?(i.e., knowing how to do something) | Insufficient knowledge about COVID-1970 and COVID-19 vaccines35,47,49,53,63,77,82,84 (number of studies [k] = 9) | |

| Environmental context and resources | What in HCWs environment influencewhat they do and how do they influence? | Limited availability and accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines (k = 1)84 | Access to and trust in reputable scientific/non-scientific information sources about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., cues to action) (k = 6)16,18,24,25,37,85 Receiving financial support during the pandemic (e.g., paid sick days) (k = 1)23 |

| Social influences | What do others do? What do others thinkof what HCWs do or what they should do?Who are they and how does thatnfluence what they do? | State/government/public health agency/media mistrust (k = 10)15,29,34,35,50,63,67,69,79,84 Negative influences of social contacts,30,40 family members,84 and political figures74 in relation to vaccine acceptance79 (k = 5) |

Trust in how hospital management has handled the pandemic (k = 2)63,67 |

| Beliefs about consequences | What are the good and bad things that can happenfrom what HCWs do and how does that influencewhether they'll do it in the future? | Concerns about vaccine safety (e.g., side-effects) (k = 30) 14,18,23,30,31,35,36,41,44,45,47,50,54,56,60,62, 63, 64, 65, 66,68,69,71,73,78,79,81, 82, 83, 84 Beliefs about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy 18,34,36,45,60,63,68,74,76,81,83 and efficacy against variants of concern specifically82 (k = 12) Concerns about rushed vaccine development (k = 10)18,23,26,31,34,45,56,69,73,82 Beliefs that vaccine not necessary (e.g., feel in good health, already protected) (k = 6) 23,29,45,66,71,82 |

Concerns about being infected by COVID-19 (e.g., perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 and its severity) (k = 10)23,26,31,33,38,40,44,47,81,86 Positive attitudes and confidence towards COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., perceived benefit) (k = 6)17,34,38,41,49,60 Belief that getting vaccinated will protect familyspecifically (k = 5)21,24,39,50,53 Belief that getting vaccinated will protect patients specifically (k = 3)24,50,53 |

| Social/professional role and identity | How does their role/responsibility (in various settings) influence whether they do or not?How does who they are as a HCW influencewhether they do something or not? Is the behaviour something they are supposed to do or is someone else responsible? | Vaccine acceptance lower among nursingprofessionals vs physicians16,20,22,25, 26, 27,32,33,54,58, 59, 60,62,63,65,68,70,72,75,81,84or dietary, housekeeping, and administrative staff79 (k = 22) | Working directly patients generally44,48,74 and with COVID-19 patients specifically20,27, 28, 29,82 (k = 8) When getting vaccinated seen as a professional24 or collective/prosocial responsibility23,49 (k = 3) Belief that vaccination for COVID-19 should be mandatory for HCWs (k = 3)34,52,66 Pharmacists who are managers/owners were more likely to accept a vaccine than pharmacy technicians (k = 1)61 An increase in the unemployment rate within the dental sector coincides with a rise in willingness for a COVID-19 vaccine (k = 1)88 Paediatric physicians more likely to accept free 80% effective vaccine vs physicians in administrative roles (k = 1)18 Being a pharmacy student vs medicine student was a significant predictor of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (k = 1)71 |

| Reinforcement | How have their experiences (good and bad) ofdoing it in the past influence whether or notthey do it? Are there incentives/rewards? | Previously tested positive for COVID-19 themselveswere more hesitant towards vaccination (k = 2)58,83 | Historical seasonal influenza vaccination (k = 25)15,17,18,20,24,25,29,33,34,40,41,46,48,52,54,63, 64, 65, 66,70,76,80,82,83 Members of families/close social network having being infected with COVID-19 (k = 2)16,71 Engaging with COVID-19 infection behaviours (i.e., personal protective behaviour) throughout the pandemic (k = 1)47 |

| Emotion | How do they feel (affect) about what they do and do those feelings influence what they do? | Fear about the consequences of contracting COVID-19 (k = 5)33,37,41,64,76 Psychological distress (stress, depression, anxiety) was associated with higher vaccine acceptance (k = 3)49,76,87 Fearing injections was independent predictor of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (k = 1)67 Job satisfaction was associated with higher vaccine acceptance (k = 1)73 |

|

| Beliefs about capabilities | Do HCWs think they can (are they confident that they can) and how does that influence whether they do it or not? What increases or decreases their confidence? | Self-efficacy/confidence in overcoming any challenges or difficulties in getting vaccinated (k = 3)70,73,86 |

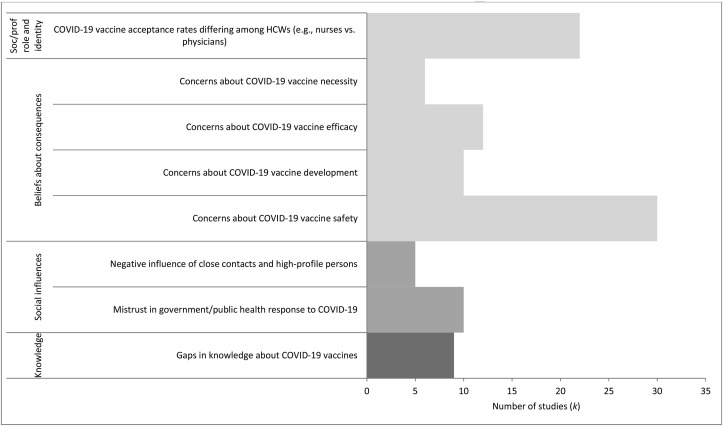

Fig. 2.

Frequency of key barriers identified within the literature (only including barriers identified in ≥3 studies). Notes. Soc/prof role and identity = Social/professional role and identity.

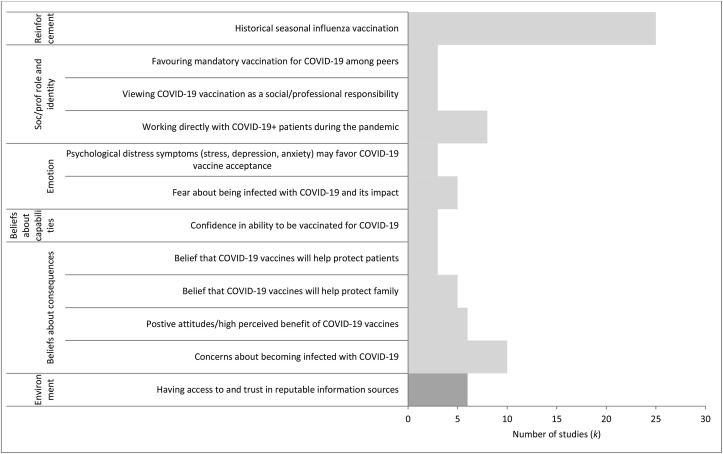

Fig. 3.

Frequency of key enablers identified within the literature (only including enablers identified in ≥3 studies). Notes. Soc/prof role and identity = Social/professional role and identity; Environment = Environmental context and resources.

TDF domains represented within the literature

Knowledge: A lack of knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines was cited as a barrier in nine studies.36,48,50,54,64,71,78,83,85 One study tested the relationship statistically between HCW knowledge and vaccination acceptance, where HCWs with ‘high’ knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines had 1.86 times greater odds of accepting a COVID-19 vaccine vs those with ‘low’ knowledge.64 A qualitative study highlighted that ‘complex information, conflicting and changing guidance, overwhelming amounts of material, and poor provision of information in other languages contributed to a lack of trust, confusion, and ultimately vaccine hesitancy’ (p8).83

Environmental context and resources: Access to and trust in reputable information sources about COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines was seen as an enabler to vaccine acceptance in six studies.17,19,25,26,38,86 Moreover, one study found that financial support such as paid sick leave during the pandemic was associated with vaccine acceptance among HCWs.24 In terms of barriers, one study found that a lack of availability and accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines was linked to lower vaccine acceptance among HCWs.85

Social influences: Ten studies found mistrust towards governments and public health bodies was associated with lower vaccination acceptance.16,30,35,36,51,64,68,70,80,85 At a more local level, two studies found that trust in how hospital management had handled the pandemic was linked to lower vaccine acceptance.64 , 68

Beliefs about consequences: This domain was one of the most frequently identified across studies and related specifically to beliefs related to vaccine safety, efficacy, and necessity. In 30 studies, safety concerns centered on the risk of possible adverse events (e.g., side effects).15,19,24,31,32,36,37,42,45,46,48,51,55,57,61,63, 64, 65, 66, 67,69,70,72,74,79,80,82, 83, 84, 85 Concerns about the speed at which COVID-19 vaccines had being developed was seen in 10 studies19 , 24 , 27 , 32 , 35 , 46 , 57 , 70 , 74 , 83. Twelve studies found that HCWs questioned the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.19 , 35 , 37 , 46 , 61 , 64 , 69 , 75 , 77 , 82, 83, 84 Moreover, beliefs about the necessity of COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., not feeling at risk because they feel in good health) were also found to be associated with lower vaccination acceptance in six studies.24 , 30 , 46 , 67 , 71 , 82

Emotion: General fear about COVID-19 was associated with higher vaccination acceptance in five studies.33,37,41,64,76

Beliefs about capabilities: Three studies found that confidence in overcoming any challenges or difficulties in getting vaccinated was associated with higher acceptance in three studies.70,73,86

Social/professional role and identity: One consistent finding was that vaccination acceptance was lower in non-physicians such as nurses.16 , 20 , 22 , 25, 26, 27 , 32 , 33 , 54 , 58, 59, 60 , 62 , 63 , 65 , 68 , 70 , 72 , 75 , 81 , 84 , 90 It may be that certain HCW groups have specific needs and concerns that need to be addressed. Moreover, eight studies found that the role of HCW providing direct care to patients generally and to COVID-19 patients specifically was associated with vaccination acceptance.20 , 27, 28, 29 , 44 , 48 , 74 , 82 Interestingly, one study found that perceived professional responsibility was associated with higher vaccination acceptance which could potentially be leveraged at the healthcare organization level.24 Furthermore, three studies reported that HCWs who believed that COVID-19 vaccination should be mandatory for HCWs were more likely to accept a vaccine.34 , 52 , 66

Reinforcement: Previous vaccination behaviour (e.g., seasonal influenza vaccine) was found to be consistently associated with higher acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine.15,17,18,20,24,25,29,33,34,40,41,46,48,52,54,63, 64, 65, 66,70,76,80,82,83

Discussion

Our rapid evidence review used an established behavioural framework to bring consistency across the rapidly expanding literature on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among HCWs to identify modifiable factors to increase vaccine uptake. Based on evidence from 74 studies published up to May 2021, we found almost two-thirds of responding HCWs were willing to accept a COVID-19 vaccine. Across studies, we identified eight (of a possible 14) domains of TDF, and 20 key barriers and enablers which may have implications for interventions seeking to promote COVID-19 vaccine uptake among HCWs. The most frequently coded TDF domains were Beliefs about consequences, Social/professional role and identity, and Reinforcement, which were broadly operationalized as concerns about the vaccine itself, HCWs in non-physician roles, and previous seasonal vaccine uptake, respectively.

HCWs frequently citing concerns about COVID-19 vaccine safety supports findings from the broader vaccination literature.91 Although this is undoubtedly a key barrier to vaccination (COVID-19 or otherwise), its frequency can be partially explained by narrow study designs focusing solely on HCW attitudes towards vaccination. As such, although some behavioural domains did not yet emerge as factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in HCWs (TDF domains: Skills, Behavioural regulation, Memory, attention and decision processes, Goals, and Optimism), there may be opportunity for considering a greater breath of possible barriers and enablers which could be guided by frameworks such as the TDF. Only one study24 in our sample had used the TDF to inform their survey design, which resulted in key insights into barriers and enablers to vaccination acceptance among Canadian HCWs, many of which extended what is known.

Addressing key barriers and enablers for HCWs should involve multiple approaches at multiple levels; therefore, a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to address the range of barriers and enablers expressed by HCWs. In Table 2 , we provide a non-exhaustive list of recommendations based on general principles from behavioural science which may help form the basis for behaviour-focused interventions to increase COVID-19 vaccination among HCWs.

Table 2.

Identified barriers to and enablers of COVID-19 vaccination acceptance among healthcare workers (HCWs) along with recommendations based on behavioural science principles.

| Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) domain | Barriers and enablers identified | Recommendations based on behavioural science principles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | |||

| Knowledge | Gaps in knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines (number of studies [k] = 9) | Address knowledge gaps through educational campaigns tailored to different groups of HCWs, disseminated from trusted sources that likely differ for different groups of HCWs; one-size-fits-all knowledge dissemination unlikely to reach those who may benefit most. | |

| Social Influences | Mistrust in government/public health response to COVID-19 (k = 10) | Help rebuild trust through transparent communication about COVID-19 vaccination and community engagement and cultural understanding, especially HCWs from equity-seeking groups. Acknowledging past harms against racialized groups validates feelings of mistrust and aims to rebuild trust by addressing inequities. | |

| Negative influence of close contacts and high-profile persons (k = 5) | Recognize the importance of people's social circles and prominent public figures and the influence they can have on intention and behaviour. Work within trusted circles and engage meaningfully. | ||

| Beliefs about consequences | Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine safety (k = 30) | Reassure and be transparent about vaccine risks using trusted sources and communication modalities that leverage risk communication tools and approaches that go beyond numerical risk and benefit data. | |

| Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine development (k = 10) | Reiterate how it was possible to develop and approve COVID-19 vaccines relatively rapidly while maintaining all the same checks and balances to ensure a rigorous vaccine development process. | ||

| Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine efficacy (k = 12) | Ensure that the effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19 and its variants of concern are clear and continue to be updated as evidence accrues. Communicate efficacy using evidenced benefit communication approaches that do not only rely on numeracy. Clarify benefits (where known) across outcomes of importance including infection, severity, side effects, hospitalization and/or death. | ||

| Concerns about COVID-19 vaccine necessity (k = 6) | Reassure the need for vaccines, emphasizing the protection of oneself and others to build towards community immunity. | ||

| Social/professional role and identity | COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates differing among HCWs (e.g., nurses vs physicians) (k = 22) | One-size-fits-all approaches are unlikely to generalize across different groups of HCWs. Working within professional circles (both formal and informal) and leveraging trusted members of each group may help to address their needs and concerns. | |

| Enablers | |||

| Environmental context and resources | Having access to and trust in reputable information sources (k = 6) | Identify and make available reputable and trustworthy sources of information sources more accessible to help counter misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines. | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Concerns about becoming infected with COVID-19 (k = 10) | Reiterate the seriousness of being infected by COVID-19 and potential longer-term consequences (e.g., ‘long-covid'). | |

| Positive attitudes/high perceived benefit of COVID-19 vaccines (k = 6) | Emphasize the benefit of vaccines, both from a medical standpoint (e.g., drawing on the benefit of previous vaccines for infectious diseases (e.g., polio)) and personal/social standpoint (e.g., returning to ‘normal’, seeing family without restrictions). | ||

| Belief that COVID-19 vaccines will help protect family (k = 5) | Leverage the prosocial nature of vaccination which will help protect others. | ||

| Belief that COVID-19 vaccines will help protect patients (k = 3) | Leverage the prosocial nature of vaccination which will help protect others in a work context. | ||

| Beliefs about capabilities | Confidence in ability to be vaccinated for COVID-19 (k = 3) | Encourage confidence in ability to be vaccinated, minimize barriers to access which may impact perceived capability and show similar others being vaccinated to help model and build confidence. | |

| Emotion | Fear about being infected with COVID-19 and its impact (k = 5) | Whilst being careful not to stoke fear, reiterate the seriousness of COVID-19 and its societal consequences (e.g., restrictions/lockdowns). | |

| Psychological distress symptoms (stress, depression, anxiety) may favor COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (k = 3) | Acknowledge that some psychological disorder-thinking (stress, depression, anxiety) may influence personal protective behaviours such as vaccination (although there must be caution with this). | ||

| Social/professional role and identity | Working directly with COVID-19+ patients during the pandemic (k = 8) | Encourage those not working in a clinical setting that COVID-19 still poses risks. | |

| Viewing COVID-19 vaccination as a social/professional responsibility (k = 3) | Instill the notion of vaccination as a professional and social responsibility, to help normalize such behaviour. | ||

| Favoring mandatory vaccination for COVID-19 among peers (k = 3) | Consider mandatory vaccination (although there must be caution with this and if considered, in conjunction with approaches that support addressing other barriers/enablers so as not to undermine trust). | ||

| Reinforcement | Historical seasonal influenza vaccination (k = 25) | Leverage successful interventions to increase seasonal influenza vaccination which may be applicable to COVID-19. | |

There was some evidence indicating that knowledge was associated with vaccination acceptance among HCWs. Knowledge, or lack thereof, is often seen as a key barrier to behaviour change which is reflected in the abundance of strategies and programs that focus solely on education and providing information. Although knowledge is undoubtedly important, it is usually insufficient as a stand-alone strategy; therefore, additional evidence-based, modifiable barriers must also be considered.92 Despite Memory, attention and decision processes being part of the TDF, no studies attempted to measure decision-making. However, it is likely that future studies collecting data on both vaccination acceptance and uptake may delve deeper into the actual decision process (e.g., framing effects and memory93), which may also tap into other domains such as Beliefs about consequences (e.g., how HCWs weighed up beliefs about vaccine necessity vs concerns about possible adverse effects).

Given that COVID-19 vaccines have been rolling out since late 2020, there is an opportunity to assess whether the same factors associated with vaccine acceptance (intention) are also associated with actual vaccination uptake (behaviour). This will provide insight into the extent vaccine intention predicts behaviour in HCWs, and whether postintentional factors are at play. Evidence from other behavioural literatures suggests a gap between intention and action and approaches for bridging this gap offer opportunities for ensuring individuals who do develop strong intentions and acceptance for the COVID-19 vaccine translate their strong intention into actual vaccination.92

Although we have made recommendations based on past learnings from behavioural science (Table 2), there is an opportunity to supplement these principle-based learnings with data from past vaccination campaign interventions94 and interventions and/or trials that have been conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic which, unfortunately, have been scarce. A recent systematic review by Schumacher and colleagues identified intervention studies seeking to increase influenza vaccination coverage in HCWs. Among 30 studies, a range of education and promotion (e.g., educational sessions), incentivization (e.g., free vaccination), organisational (e.g., on-site vaccination), and policy (e.g., mandatory vaccination policy) strategies were used with mandatory vaccination policies achieving the highest overall vaccination coverage.94 Despite being a topic of some controversy, several countries including England, Australia, France, and Germany have decided to implement mandatory COVID-19 vaccines for HCWs with other countries likely to follow suit.95

There is also a need for more research to be conducted with HCWs from equity-seeking groups to help better inform how best to support greater vaccination. Assessing barriers and enablers to vaccine acceptance that equity-seeking groups experience may provide valuable insights into factors driving observed disparities, especially when considered alongside the key barriers and enablers to better support each group.96, 97

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, our rapid review methodology did not allow for a study quality assessment to be done, which means that we are unable to make a judgement of the quality of the evidence being synthesised. Second, given our desire to ensure that emerging data were captured, we included preprints that had not yet been peer-reviewed. Third, 15 of 74 papers included were conducted before COVID-19 vaccines had been approved (November 2020); therefore, questioning about COVID-19 vaccination would have been hypothetical. However, similar determinants of vaccines were found across all studies, which suggests that opinions about hypothetic vs actual vaccines were broadly consistent in our sample. Fourth, our last search was done in May 2021, meaning that recent studies in this topic area are absent.

Conclusion

Our rapid review identified several behavioural determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among HCWs which could help inform vaccination messaging, campaigns, programs, and policy to support HCWs globally. This review should help decision-makers to navigate this complex area which requires an evidence-based approach to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake. We have demonstrated utility in applying behavioural frameworks such as the TDF to help bring coherence to an emerging literature. An advantage of synthesising the existing literature with such frameworks is three-fold: first, it helps to identify key determinants represented in the literature; second, it allows one to consider if there are under-considered determinants deserving of greater attention; and third, it enables linkage between behavioural determinants and behaviour change techniques.6 Given the paucity of theory-informed research in our sample, we encourage the use of such frameworks to help inform the development of surveys and interview guides to ensure that the widest set of potential determinants to vaccination are explored.

Author statements

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Rhode Island Department of Health. The opinions, results, and conclusions are those of the authors and are independent of the funder. No endorsement by the Public Health Agency of Canada or the Rhode Island Department of Health is intended or should be inferred. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Ethical approval was not required given that our study design was a rapid evidence review.

Ethical approval

None sought.

Funding

None declared.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.06.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University . 2021. COVID-19 dashboard.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kavanagh M.M., Gostin L.O., Sunder M. Vaccine doses to address global vaccine inequity and end the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2021;326:219–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Gallagher E., Simmons R., Thelwall S., et al. Effectiveness of covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkins L., Francis J., Islam R., O’Connor D., Patey A., Ivers N. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12 doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cane J., O’Connor D., Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michie S., Johnston M., Abraham C., Lawton R., Parker D., Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. BMJ Qual Saf. 2005;14 doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michie S., Richardson M., Johnston M., Abraham C., Francis J., Hardeman W. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46 doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khangura S., Konnyu K., Cushman R., Grimshaw J., Moher D. Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst Rev. 2012;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott J., Lawrence R., Minx J.C., Oladapo O.T., Ravaud P., Tendal Jeppesen B., et al Decision makers need constantly updated evidence synthesis. 2021 doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03690-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Public Health Agency of Canada . Public Health Agency of Canada; 2021. Evergreen rapid review on COVID-19 vaccine knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors – update 6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMaster Health Forum . McMaster Health Forum; 2020. What is known about strategies for encouraging vaccine acceptance and addressing vaccine hesitancy or uptake? [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMaster Health Forum . McMaster Health Forum; 2021. COVID-19 Living Evidence Profile #1: what is known about anticipated COVID-19 vaccine roll-out elements? [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ontario Ministry of Health . Ontario Ministry of Health; 2021. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among health care workers. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abuown A., Ellis T., Miller J., Davidson R., Kachwala Q., Medeiros M., et al COVID-19 vaccination intent among London healthcare workers. Occup Med Published Online First. May 2021;18 doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqab057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agyekum M.W., Afrifa-Anane G.F., Kyei-Arthur F., Addo B. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination among health care workers in Ghana. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.11.21253374. 2021.03.11.21253374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Metwali B.Z., Al-Jumaili A.A., Al-Alag Z.A., Sorofman B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jep.13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarado-Socarras J.L., Vesga-Varela A.L., Quintero-Lesmes D.C., Fama-Pereira M.M., Serrano-Diaz N.C., Vasco M., et al Perception of COVID-19 vaccination amongst physicians in Colombia. Vaccines. 2021:9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry M., Temsah M.H., Alhuzaimi A., Alamro N., Al-Eyadhy A., Aljamaan F., et al COVID-19 vaccine confidence and hesitancy among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional survey from a MERS-CoV experienced nation. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.09.20246447. 2020.12.09.20246447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauernfeind S., Hitzenbichler F., Huppertz G., Zeman F., Koller M., Schmidt B., et al. Brief report: attitudes towards Covid-19 vaccination among hospital employees in a tertiary care university hospital in Germany in December 2020. Infection. May 2021;20 doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01622-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry S.D., Johnson K.S., Myles L., Herndon L., Montoya A., Fashaw S., et al Lessons learned from frontline skilled nursing facility staff regarding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jgs.17136. n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castañeda-Vasquez D.E., Ruiz-Padilla J.P., Botello-Hernandez E. Vaccine hesitancy against SARS-CoV-2 in health personnel of northeastern Mexico and its determinants. J Occup Environ Med. 2021 doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002205. Publish Ahead of Print. https://journals.lww.com/joem/Fulltext/9000/Vaccine_Hesitancy_against_SARS_CoV_2_in_Health.97927.aspx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew N.W.S., Cheong C., Kong G., Phua K., Ngiam J.N., Tan B.Y.Q., et al An Asia-Pacific study on healthcare workers' perceptions of, and willingness to receive, the COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;106:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desveaux L., Savage R.D., Tadrous M., Kithulegoda N., Thai K., Stall N.M., et al Beliefs associated with intentions of non-physician healthcare workers to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in ontario, Canada. medRxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Gennaro F., Murri R., Segala F.V., Cerruti L., Abdulle A., Saracino A., et al Attitudes towards anti-SARS-CoV2 vaccination among healthcare workers: results from a national survey in Italy. Viruses. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/v13030371. 10.3390/v13030371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Giuseppe G., Pelullo C.P., Della Polla G., Montemurro M.V., Napolitano F., Pavia M., et al Surveying willingness toward SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of healthcare workers in Italy. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2021.1922081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dror A.A., Eisenbach N., Taiber S., Morozov N.G., Mizrachi M., Zigron A., et al Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35:775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dzieciolowska S., Hamel D., Gadio S., Dionne M., Gagnon D., Robitaille L., et al Covid-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal among Canadian healthcare workers: a multicenter survey. Am J Infect Control Published Online First. April 2021;28 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.04.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fares S., Elmnyer M.M., Mohamed S.S., Elsayed R. COVID-19 vaccination perception and attitude among healthcare workers in Egypt. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12 doi: 10.1177/21501327211013303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fouogue J.T., Noubom M., Kenfack B., Dongmo N.T., Tabeu M., Megozeu L., et al Poor knowledge of COVID-19 and unfavourable perception of the response to the pandemic by healthcare workers at the Bafoussam Regional Hospital (West Region - Cameroon) medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.20.20178970. 2020.08.20.20178970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu C. Acceptance and preference for COVID-19 vaccination in health-care workers (HCWs) medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20060103. 2020.04.09.20060103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gadoth A., Halbrook M., Martin-Blais R., Gray A., Tobin N.H., Ferbas K.G., et al Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in Los Angeles. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.18.20234468. 2020.11.18.20234468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagneux-Brunon A., Detoc M., Bruel S., Tardy B., Rozaire O., Frappe P., et al Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: a cross-sectional survey. J Hosp Infect. 2021;108:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gönüllü E., Soysal A., Atıcı S., Engin M., Yeşilbaş O., Kasap T., et al. Pediatricians' COVID-19 experiences and views on the willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional survey in Tu8rkey. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1896319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grumbach K., Judson T., Desai M., Jain V., Lindan C., Doernberg S.B., et al. Association of race/ethnicity with likeliness of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among health workers and the general population in the san francisco bay area. JAMA Intern Med Published Online First. March 2021;30 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison J., Berry S., Mor V., Gifford D. “Somebody like me”: understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among staff in skilled nursing facilities. J Am med dir assoc. March 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.03.012. published online first: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hussein A.A.M., Galal I., Makhlouf N.A., Makhlouf H.A., Abd-Elaal H.K., Kholief K.M., et al A national survey of potential acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines in healthcare workers in Egypt. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.11.21249324. 2021.01.11.21249324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huynh G., Tran T., Nguyen H., Pham L. COVID-19 vaccination intention among healthcare workers in Vietnam. Asian Pac. J Trop Med. 2021;14:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain V., Doernberg S.B., Holubar M., Huang B., Marquez C., Brown L., et al Healthcare personnel knowledge, motivations, concerns and intentions regarding COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.02.19.21251993. 2021.02.19.21251993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanyike A.M., Olum R., Kajjimu J., Ojilong D., Akech G.M., Nassozi D.R., et al Acceptance of the coronavirus disease-2019 vaccine among medical students in Uganda. Trop Med Health. 2021;49:37. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00331-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaplan A.K., Sahin M.K., Parildar H., Adadan Guvenc I. The willingness to accept the COVID-19 vaccine and affecting factors among healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional study in Turkey. Int J Clin Pract. 2021 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14226. n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karagiannidis C., Spies C., Kluge S., Marx G., Janssens U. Impfbereitschaft unter intensivmedizinischem Personal: Ängsten entgegenwirken. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfallmed. 2021;116:216–219. doi: 10.1007/s00063-021-00797-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King W.C., Rubinstein M., Reinhart A., Mejia R.J. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy January-March 2021 among 18-64 year old US adults by employment and occupation. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.20.21255821. 2021.04.20.21255821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kociolek L.K., Elhadary J., Jhaveri R., Patel A.B., Stahulak B., Cartland J. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy among children's hospital staff: a single-center survey. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42:775–777. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konopińska J., Obuchowska I. Intention to get COVID-19 vaccinations among ophthalmology residents in Poland: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kose S., Mandiracioglu A., Sahin S., Kaynar T., Karbus O., Ozbel Y. Vaccine hesitancy of the COVID-19 by health care personnel. Int J Clin Pract. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13917. n/a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kukreti S., Lu M.Y., Lin Y.H., Strong C., Lin C.Y., Ko N.Y., et al Willingness of taiwan's healthcare workers and outpatients to vaccinate against COVID-19 during a period without community outbreaks. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuter B.J., Browne S., Momplaisir F.M., Feemster K.A., Shen A.K., Green-McKenzie J., et al Perspectives on the receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine: a survey of employees in two large hospitals in Philadelphia. Vaccine. 2021;39:1693–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwok K.O., Li K.K., WEI W.I. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: a survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;114:103854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ledda C., Costantino C., Cuccia M., Maltezou H.C., Rapisarda V. Attitudes of healthcare personnel towards vaccinations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18:2703. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lucia V.C., Kelekar A., Afonso N.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health Published Online First. December 2020;26 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maltezou H.C., Pavli A., Dedoukou X., Georgakopoulou T., Raftopoulos V., Drositis I., et al Determinants of intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 among healthcare personnel in hospitals in Greece. Infect Dis Health Published Online First. March 2021;31 doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manning M.L., Gerolamo A.M., Marino M.A., Hanson-Zalot M.E., Pogorzelska-Maziarz M. COVID-19 vaccination readiness among nurse faculty and student nurses. Nurs Outlook Published Online First. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maraqa B., Nazzal Z., Rabi R., Sarhan N., Al-Shakhra K., Al-Kaila M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Palestine: a call for action. Prev Med. 2021;149:106618. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mascarenhas A.K., Lucia V.C., Kelekar A., Afonso N.M. Dental students' attitudes and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccine. J Dent Educ. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jdd.12632. n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCabe S.D., Hammershaimb E.A., Cheng D., Shi A., Shyr D., Shen S., et al Unraveling attributes of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the U.S.: a large nationwide study. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.05.21254918. 2021.04.05.21254918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer M.N., Gjorgjieva T., Rosica D. Trends in health care worker intentions to receive a COVID-19 vaccine and reasons for hesitancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e215344. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5344. e215344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moniz M.H., Townsel C., Wagner A.L., Zikmund-Fisher B.J., Hawley S., Jiang C., et al COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in a United States medical center. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.29.21256186. 2021.04.29.21256186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nohl A., Afflerbach C., Lurz C., Brune B., Ohmann T., Weichert V., et al Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among front-line health care workers: a nationwide survey of emergency medical services personnel from Germany. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nzaji M.K., Ngombe L.K., Mwamba G.N., Ndala D.B.B., Miema J.M., Lungoyo C.L., et al Acceptability of vaccination against COVID-19 among healthcare workers in the democratic republic of the Congo. Pragmatic Observational Res. 2020;11:103. doi: 10.2147/POR.S271096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ontario College of Pharmacists . Ontario College of Pharmacists; 2021. COVID-19 vaccine administration participation readiness survey summary. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papagiannis D., Malli F., Raptis D.G., Papathanasiou I.V., Fradelos E.C., Daniil Z., et al Assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of health care professionals in Greece before the outbreak period. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020:17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paris C., Bénézit F., Geslin M., Polard E., Baldeyrou M., Turmel V., et al COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers. Infect Dis. May 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.04.001. Now Published Online First: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patelarou E., Galanis P., Mechili E.A., Argyriadi A., Argyriadis A., Asimakopoulou E., et al Factors influencing nursing students' intention to accept COVID-19 vaccination – a pooled analysis of seven countries. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.22.21250321. 2021.01.22.21250321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petravić L., Arh R., Gabrovec T., Jazbec L., Rupčić N., Starešinič N., et al Factors affecting attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: an online survey in Slovenia. Vaccines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Qattan A.M.N., Alshareef N., Alsharqi O. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front Med. 2021;8:83. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.644300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rabi R., Maraqa B., Nazzal Z., Zink T. Factors affecting nurses' intention to accept the COVID-9 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. Publ Health Nurs. 2021 doi: 10.1111/phn.12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Raftopoulos V., Iordanou S., Katsapi A., Dedoukou X., Maltezou H.C. A comparative online survey on the intention to get COVID-19 vaccine between Greek and Cypriot healthcare personnel: is the country a predictor? Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1896907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rehman K., Hakim M., Arif N., Islam S.U., Saboor A., Asif M., et al COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, barriers and facilitators among healthcare workers in Pakistan. Res Sq. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 69.SafeCare- B.C. 2020. Briefing note: COVID-19 vaccine survey. SafeCare-BC. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saied S.M., Saied E.M., Kabbash I.A., Abdo S.A.E.F. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaw J., Stewart T., Anderson K.B., Hanley S., Thomas S.J., Salmon D.A., et al Assessment of US healthcare personnel attitudes towards coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in a large university healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis Published Online First. January 2021;25 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.She R., Chen X., Li L., Li L., Huang Z., Lau J.T.F. Factors associated with behavioral intention of free and self-paid COVID-19 vaccination based on the social cognitive theory among nurses and doctors in China. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021:1–25. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shekhar R., Sheikh A.B., Upadhyay S., Singh M., Kottewar S., Mir H., et al COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines. 2021:9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singhania N., Kathiravan S., Pannu A.K. Acceptance of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine among health-care personnel in India: a cross-sectional survey during the initial phase of vaccination. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021:S1198–S1743. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.03.008. X(21)00143-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szmyd B., Karuga F.F., Bartoszek A., Staniecka K., Siwecka N., Bartoszek A., et al Attitude and behaviors towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study from Poland. Vaccines. 2021:9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Temsah M.H., Barry M., Aljamaan F., Alhuzaimi A., Al-Eyadhy A., Saddik B., et al Adenovirus and RNA-based COVID-19 vaccines: perceptions and acceptance among healthcare workers. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.22.20248657. 2020.12.22.20248657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.The Canadian PSW Network . The Canadian PSW Network; 2021. COVID-19 vaccination survey. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Unroe K.T., Evans R., Weaver L., Rusyniak D., Blackburn J. Willingness of long-term care staff to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: a single state survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:593–599. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verger P., Scronias D., Dauby N., Adedzi K.A., Gobert C., Bergeat M., et al Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada. Euro Surveill. 2020;2021(26):2002047. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang J., Feng Y., Hou Z., Lu Y., Chen H., Ouyang L., et al Willingness to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine among healthcare workers in public institutions of Zhejiang Province, China. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1909328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang K., Wong E.L.Y., Ho K.F., Cheung A.W.L., Chan E.Y.Y., Yeoh E.K., et al. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine. 2020;38:7049–7056. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woolf K., McManus I.C., Martin C.A., Nellums L.B., Guyatt A.L., Melbourne C., et al, Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in United Kingdom healthcare workers: Results from the UK-REACH prospective nationwide cohort study Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in United Kingdom healthcare workers: results from the UK-REACH prospective nationwide cohort study. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.26.21255788. 2021.04.26.21255788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yigit M., Ozkaya-Parlakay A., Senel E. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance of healthcare providers in a tertiary Pediatric hospital. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–5. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1918523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Youssef D., Abbas L.A., Berry A., Youssef J., Hassan H. Determinants of acceptance of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) vaccine among Lebanese health care workers using health belief model. v1Res Sq. May 2021;6 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-294775/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu Y., Lau J.T.F., She R., Chen X., Li L., Li L., et al Prevalence and associated factors of intention of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers in China: application of the Health Belief Model. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1909327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yurttas B., Poyraz B.C., Sut N., Ozdede A., Oztas M., Uğurlu S., et al Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with rheumatic diseases, healthcare workers and general population in Turkey: a web-based survey. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1105–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zigron A., Dror A.A., Morozov N.G., Shani T., Haj Khalil T., Eisenbach N., et al COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among dental professionals based on employment status during the pandemic. Front Med. 2021;8:13. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.618403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Crawshaw J., Konnyu K., Castillo G., van Allen Z., Trehan N., Gauvin F.P., et al . 2021. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and uptake among the general public: a living behavioural science evidence synthesis (v5, Aug 31 st, 2021)https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jacob-Crawshaw/publication/354551157_Gen_Pub_Vaccination_Living_Behavioural_Science_Evidence_Synthesis_v5_Aug_31/links/613f4f7c90130b1e19d67ec6/Gen-Pub-Vaccination-Living-Behavioural-Science-Evidence-Synthesis-v5-Aug-31.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oliver K., Raut A., Pierre S., Silvera L., Boulos A., Gale A., et al Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine receipt at two integrated healthcare systems in New York City: a Cross sectional study of healthcare workers. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.24.21253489. 2021.03.24.21253489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paterson P., Meurice F., Stanberry L.R., Glismann S., Rosenthal S.L., Larson H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–6706. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Presseau J., Desveaux L., Allen U. Behavioural science principles for supporting COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake among Ontario health care workers. Sci Briefs Ont COVID-19 Sci Advis Table. 2021;2:12. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacobson Vann J.C., Jacobson R.M., Coyne-Beasley T., Asafu-Adjei J.K., Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Published Online First. 2018 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schumacher S., Salmanton-García J., Cornely O.A., Mellinghoff S.C. Increasing influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers: a review on campaign strategies and their effect. Infection. 2021;49:387–399. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reuters . 2021. Countries making COVID-19 vaccines mandatory. Reuters.https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/countries-making-covid-19-vaccines-mandatory-2021-08-16/ [Google Scholar]

- 95.Castillo G., Ndumbe-Eyoh S., Crawshaw J., Smith M., Trehan N., Gauvin F.P., et al. 2021. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination in Black communities in Canada: a behavioural analysis.https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default-source/product-documents/living-evidence-syntheses/covid-19-living-evidence-synthesis-4.5–-black-communities-and-vaccine-confidence.pdf?sfvrsn=80feea5c_5 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Castillo G., O’Gorman C.M., Crawshaw J., Smith M., Trehan N., Gauvin F.P., et al. 2021. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination among people experiencing homelessness and precarious housing in Canada: a behavioural analysis.https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default-source/product-documents/living-evidence-syntheses/covid-19-living-evidence-synthesis-4.5–-vaccine-confidence-among-homeless-and-housing-precarious-populations.pdf?sfvrsn=3034ef6b_5 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Castillo G., Montesanti S., Crawshaw J., Smith M., Trehan N., Gauvin F.P., et al. 2021. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccination among Indigenous peoples in Canada: a behavioural analysis.https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default-source/product-documents/living-evidence-syntheses/covid-19-living-evidence-synthesis-4.5–-indigenous-peoples-and-vaccine-confidence.pdf?sfvrsn=97976116_5 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.