Abstract

We examined the associations between the developmental timing of interpersonal trauma exposure (IPT) and three indicators of involvement in and quality of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: relationship status, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use. We further examined whether these associations varied in a sex-specific manner. In a sample of emerging adult college students (N = 12,358; 61.5% female) assessed longitudinally across the college years, we found precollege IPT increased the likelihood of being in a relationship, while college-onset IPT decreased the likelihood. Precollege and college-onset IPT predicted lower relationship satisfaction, and college-onset IPT predicted higher partner alcohol use. There was no evidence that associations between IPT and relationship characteristics varied in a sex-specific manner. Findings indicate that IPT exposure, and the developmental timing of IPT, may affect college students’ relationship status. Findings also suggest that IPT affects their ability to form satisfying relationships with prosocial partners.

Keywords: Interpersonal trauma, Romantic relationships, College students, Emerging adulthood

Epidemiological studies suggest that most individuals in the US will be exposed to trauma at some point in their lifetime (Benjet et al., 2016; Kilpatrick et al., 2013), with interpersonal trauma (IPT; i.e., physical assault, sexual assault, other unwanted/uncomfortable sexual experiences) exposure being a particularly potent form of trauma that is prevalent during adolescence and emerging adulthood (Breslau et al., 2008). Notably, estimates suggest that 39% of first-year college students report lifetime IPT exposure (Overstreet et al., 2017). Findings from extant research suggests that exposure to IPT is associated with increased likelihood of psychiatric and substance use disorders (Kessler et al., 2005; Keyes et al., 2011). Building off of longstanding theory regarding the stress-buffering role of relationships (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Umberson et al., 2010), in an earlier study we found evidence that relationship status and partner alcohol use moderated the associations between IPT and alcohol use in an emerging adult college student sample (Smith et al., 2021). However, what remains less clear is whether and how these IPT exposures might be associated with relationship outcomes in and of themselves. In particular, it has been hypothesized that trauma exposure may disrupt the resolution of key developmental tasks (Cicchetti & Handley, 2019). Among emerging adults, an especially salient developmental task is the formation and exploration of romantic relationships (Arnett, 2004; Shulman & Connolly, 2013; Umberson et al., 2010). To this end, our primary goal here was to examine relationship formation, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use as a function of timing of IPT exposure among a sample of emerging adult college students.

Associations Between Trauma and Romantic Relationships

There is relatively little direct knowledge of the associations between IPT exposure and relationship formation among college students, representing a significant gap in the literature. Yet complementary bodies of research suggests that exposure to broad trauma may impact individuals’ ability to form and maintain romantic relationships (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Taft et al., 2011). For example, individuals exposed to traumatic events earlier in development are more likely than those without trauma exposure to have insecure (i.e., anxious or avoidant; Owen et al., 2012) or avoidant attachment styles (McCarthy & Taylor, 1999), which may impede their ability to form romantic relationships. Further, individuals exposed to traumatic events are less likely than those without trauma exposure to develop positive self-concepts (Goodman et al., 2010; Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2011), which is concerning because having a positive self-concept is prospectively associated with bonded love in young adulthood (Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). Thus, extrapolating from extant research on the pathogenic effects of broad trauma, exposure to IPT during emerging adulthood likely negatively impacts the ways in which individuals connect with potential romantic partners, such that individuals exposed to IPT may be less likely to form romantic partnerships. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to directly study these associations.

For those in romantic relationships, it is well-established that exposure to traumatic events may impede individuals’ ability to maintain high-quality and stable partnerships (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Taft et al., 2011; Zamir, 2021). Insecure attachment styles, which are more common among those with a history of traumatic exposures, may negatively influence later relationship satisfaction (Lassri et al., 2016) and quality (McCarthy & Taylor, 1999). There is also evidence that individuals who experience traumatic events in adulthood become less engaged and have more negative interactions with their partners, which can lead to decreased satisfaction over time (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Whisman, 2014). Dissatisfying relationships are associated with increased psychological distress, negative affect, and hostility (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Lewis et al., 2006; Robles et al., 2014), as well as less willingness to engage in problem-solving behaviors (Marshal, 2003). Thus, exposure to traumatic events, including IPT, may negatively impact the ways in which individuals interact with their romantic partners and the satisfaction they derive from their relationships. Despite this robust line of research, the majority of these prior studies have focused on broad trauma in adult samples using cross-sectional research designs. This raises questions about whether these same patterns of effects are observed among college students exposed specifically to IPT, a particularly potent form of trauma, and whether these effects endure over time.

Lastly, little is known about the associations between IPT exposure and partner selection, representing another important gap in the literature. Nevertheless, extant literature suggests that individuals exposed to stressful life events may be more likely to select deviant partners (Quinton et al., 1993; Zoccolillo et al., 1992). The extent to which individuals select deviant romantic partners has implications for one’s own health outcomes and psychosocial adjustment, including social connectedness, stress levels, and substance use (Umberson et al., 2010). For example, in prior work, we found evidence that partner substance use exacerbated the pathogenic association between IPT and alcohol use in an emerging adult college student sample (Smith et al., 2021), giving rise to the question of whether individuals exposed to IPT are likely to select partners high in substance use. As previously noted, exposure to traumatic events is associated with having insecure attachment styles (McCarthy & Taylor, 1999; Owen et al., 2012) and poor emotion regulation (Goodman et al., 2010; Ogle et al., 2013), which are in turn associated with using substances to cope (Molnar et al., 2010). It is also well-established that individuals tend to assortatively pair with romantic partners similar to themselves and supportive of their behaviors (McPherson et al., 2001; Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007; Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1993). Thus, it follows that individuals exposed to trauma may select into relationships with partners high in substance use because of similarities and compatibility related to coping styles. Taken together, these converging lines of evidence suggest that IPT exposure may influence the types of romantic partners individuals choose.

Developmental Timing and Sex-Specific Effects

An important consideration in understanding the associations between IPT and romantic relationships is developmental timing and duration of effect. Trauma exposure earlier in development is more strongly associated with negative psychological health and psychosocial functioning compared to trauma experienced later in life (Cloitre et al., 2009; Ogle et al., 2013), with prospective studies indicating that trauma that occurs during early life can have lasting effects on developmental trajectories (e.g., Kim & Cicchetti, 2003; Norman et al., 2012; Oshri et al., 2018). For example, research suggests that trauma exposure during childhood and adolescence can impact key socioemotional developmental processes, including emotion regulation, attachment formation, sense of self (Goodman et al., 2010; Ogle et al., 2013), and neurobiological responses to stress (Stevens et al., 2018). In other words, traumatic experiences may scaffold the development of competence (or lack thereof) in romantic relationships. Trauma exposure that occurs later in development, such as during emerging adulthood, may undermine positive schemas and achievement in psychosocial domains of functioning (e.g., educational achievement, social relationships; Berntsen et al., 2011). Yet, it remains unclear whether emerging adulthood trauma has similarly enduring effects on romantic relationships. To answer this question, we examined whether IPT exposure that occurs at different points in development may have differential effects on college students’ romantic relationship outcomes, and whether IPT exposure in emerging adulthood has lagged associations with their relationship characteristics over a one-year period.

A second consideration in the associations between IPT and relationship characteristics is understanding potential sex/gender differences. (We recognize that, although sex and gender are often highly correlated, they are not synonymous. However, prior studies in this area have used various operational definitions making research in this area somewhat convoluted. For simplicity, we use the term sex differences.) Research suggests that females tend to experience more adverse outcomes following trauma exposure compared to males, such as higher rates of trauma-related distress and anxiety (Overstreet et al., 2017) and greater risk for PTSD (Breslau et al., 1999; Kessler, 1995; Stevens et al., 2018). For example, the prevalence of PTSD is approximately twice as high in females compared to males (Breslau et al., 1999; Perrin et al., 2014), and these sex differences are most pronounced during emerging adulthood (Breslau et al., 1999). Prior research indicates that symptoms of PTSD (e.g., increased vigilance, social withdrawal) may interfere with one’s ability to form or maintain a romantic relationship (Monson et al., 2009; Taft et al., 2011); moreover, trauma-related distress and PTSD are associated with higher levels of relationship discord and dissatisfaction (Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Taft et al., 2011). In view of these earlier findings, we hypothesized that associations between IPT and relationship characteristics may vary was a function of sex, with stronger effects observed for females than males.

Current Study

Despite strong evidence that broad trauma is associated with poor romantic relationship quality in adults (Zamir, 2021), questions remain. Namely, it is unclear whether these patterns of effects are relevant to relationship formation and partner selection among college students, whether the same pattern of effects are observed for IPT specifically, and whether these effects endure over time. To address these gaps, the present study aimed to examine the associations between IPT and romantic relationship formation (i.e., relationship status) and relationship characteristics (i.e., relationship satisfaction, partner alcohol use) using a developmental lens. Using a sample of emerging adult college students from a large, longitudinal project, we examined 1) whether precollege IPT predicted relationship formation or characteristics; 2) whether college-onset IPT had concurrent or lagged associations with relationship formation or characteristics; and 3) whether any of these associations varied in a sex-specific manner.

We hypothesized that college students exposed to precollege or concurrent college-onset IPT would have a greater likelihood of being single versus being in a committed relationship. For those in a relationship, we hypothesized that those exposed to precollege or concurrent college-onset IPT, relative to those not exposed to IPT, would report lower relationship satisfaction and higher partner alcohol use. Next, we hypothesized that college-onset IPT would have lagged associations with relationship characteristics. We hypothesized that individuals exposed to college-onset IPT would have a greater likelihood of being single versus being in a relationship the following year. Similarly, for those in a relationship, we hypothesized that those exposed to college-onset IPT would report lower relationship satisfaction and higher partner alcohol use the following year. Lastly, we hypothesized that the pattern of effects would be stronger for females compared to males. Study hypotheses were preregistered on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/7t5mf.

Methods

Participants

Data were from the Spit for Science project, a university-wide longitudinal study focused on substance use and behavioral health among college students at a large, urban, four-year public university (Dick et al., 2014). The Spit for Science project began in fall 2011, and new cohorts were recruited in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2017 (N = 12,358). Each year, all incoming freshmen over age 18 were invited to participate in the Spit for Science study. Those who consented to participate completed the baseline survey during the fall or spring of their freshman year and were invited to complete follow-up surveys every spring thereafter. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools (Harris et al., 2009).

Participants were included in the present study if they completed surveys at baseline and at least one follow-up (Mfollow-up assessments = 1.70, range = 1-4); 57.3%, 36.0%, 25.3%, and 13.7% of participants completed one, two, three, and four follow-up assessments, respectively. Follow-up data for the fifth cohort (2017) were unavailable at the time of data analysis and were therefore excluded. We derived two analytic subsamples from the full Spit for Science sample. The first subsample included individuals who were part of the analyses focused on relationship status as an outcome of IPT exposure (n = 1,132). The second subsample included those who were part of the analyses focused on relationship satisfaction and partner alcohol use as outcomes of IPT exposure. This subsample was limited to those individuals who were in a relationship at one or more assessments and were thus eligible to answer questions about their relationships (n = 1,913).1

Measures

Interpersonal trauma exposure.

Precollege IPT was a time-invariant measure assessed at baseline, and college-onset IPT was a time-varying measure assessed at each follow-up. IPT exposure was measured as participants’ self-reported exposure to potentially traumatic events, assessed via the following items from the abbreviated Life Events Checklist (Gray et al., 2004): physical assault, sexual assault, and other unwanted or uncomfortable sexual experiences. At the baseline assessment, participants were coded as having precollege IPT if they reported having ever experiencing a physical assault, sexual assault, or other unwanted sexual experience (Berenz et al., 2016; Hawn et al., 2018; Overstreet et al., 2017). Participants were coded as having college-onset IPT if they reported experiencing any potentially traumatic events “since starting college” during the spring of their freshman year, or “in the last 12 months” at any subsequent follow-up assessments (i.e., years two through four; Berenz et al., 2016; Hawn et al., 2018; Overstreet et al., 2017). Precollege and college-onset IPT were coded dichotomously, with participants exposed to IPT (1) or not exposed to IPT (0).

Relationship status.

Relationship status was a time-varying measure assessed at each follow-up assessment in which participants described their current relationship status by selecting one of the following: “not dating,” “dating several people,” “dating one person exclusively,” “engaged,” “married,” or “married but separated.” Relationship status was collapsed into two categories: in a committed relationship (1) and not in a committed relationship (0). Participants who identified as dating one person exclusively, being engaged, or being married were coded as being in a committed relationship. Those who identified as not dating, dating several people, and married but separated were coded as not in a committed relationship. Our decision to collapse participants who indicated that they were not dating anyone, dating several people, and married but separated into “not in a committed relationship” was guided by the small sample sizes of the latter two relationship statuses (< 12.1% and < 0.12% of the sample, respectively).

Relationship satisfaction.

Relationship satisfaction was a time-varying measure, comprised of three items from the Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick et al., 1998), assessed at each follow-up assessment. Participants in a committed relationship at the time of assessment reported on their general relationship satisfaction, how well their partner meets their needs, and how good their relationship is compared to most. Response options ranged from “not at all” (0) to “a lot/very much” (100) and were presented on a slider scale that participants could move to indicate their response. Responses were averaged across all three items and transformed to a one to seven scale. Higher scores indicated higher relationship satisfaction.

Partner alcohol use.

Partner alcohol use was a time-varying measure, comprised of two items adapted from a measure of peer deviance (Kendler, Jacobson, Myers, & Eaves, 2008; Smith et al., 2021), assessed at each follow-up assessment. Participants in a committed relationship at the time of assessment reported how often they perceived their partner “drinks alcohol” and “has a problem with alcohol (like hangovers, fights, accidents).” Participants responded using a Likert-type scale ranging from “never” (1) to “every day” (5). A composite score for partner alcohol use was created from the sum of the endorsed items (inter-item r = 0.46). Higher total scores indicated higher levels of partner alcohol use (Kendler, Jacobson, Myers, & Eaves, 2008).

Covariates.

Covariates included age, race/ethnicity, time in school, and cohort. Sex was included as a covariate for the first two research aims and used as a moderator for the third research aim. All covariates, except time in school and cohort, were self-report items, measured at baseline. Age was measured in years. Race/ethnicity was coded as White, African American/Black, Asian, Hispanic/Latino, other race/ethnicity, and more than one race/ethnicity. Participants who reported their race/ethnicity as unknown or chose not to answer were coded as missing. Sex was coded as male (0) or female (1). Because of the longitudinal nature of the study, time in school was measured in years to correspond to each year in college at which participants were assessed. Finally, cohort corresponded to the year in which participants were recruited, with cohort one set as the reference group. Covariate selection was informed by prior analyses in this sample in which we found that relationship status and partner alcohol use, but not relationship satisfaction, moderated the associations between IPT and alcohol use (Smith et al., 2021). In view of this, and because all covariates were significantly correlated with at least one outcome of interest (i.e., relationship status, relationship satisfaction, or partner alcohol use), we opted to retain these measures as covariates.

Data Analysis Plan

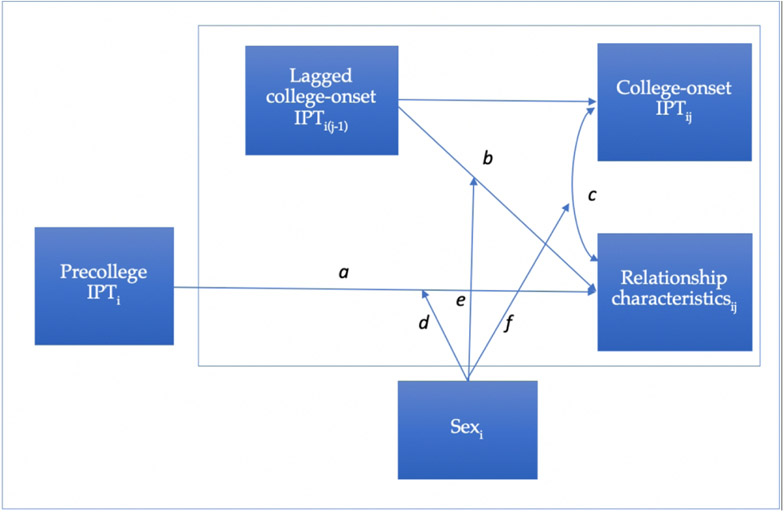

We conducted a series of analyses to examine 1) whether precollege and college-onset IPT predicted relationship status, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use; 2) whether college-onset IPT had lagged or concurrent associations with these relationship characteristics; and 3) whether any of these associations varied in a sex-specific manner. Figure 1 represents the conceptual model for the research aims. Pathway a represents the effect of precollege IPT on each relationship characteristic. Pathway b represents the lagged associations between college-onset IPT and each relationship characteristic. Pathway c represents the concurrent associations between college-onset IPT and each relationship characteristic. Pathway d represents the moderating effects of sex on the associations between precollege IPT and each relationship characteristic. Lastly, pathways e and f represent the moderating effects of sex on the lagged and concurrent associations between IPT and each relationship characteristic, respectively. Separate models were run for relationship status, relationship satisfaction, partner alcohol use outcomes. We retained a p-value threshold of < .05 because each relationship characteristic represents a unique construct.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for analyses examining 1) whether precollege and college-onset interpersonal trauma (IPT) predicted relationship status, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use; 2) whether college-onset IPT had lagged or concurrent associations with these relationship characteristics; and 3) whether any of these associations varied in a sex-specific manner. The pathway denoted by subscript a represents the effect of precollege IPT on each relationship characteristic. The pathway denoted by subscript b represents the lagged associations between college-onset IPT and each relationship characteristic. The pathway denoted by subscript c represents the concurrent associations between college-onset IPT and each relationship characteristic. The pathway denoted by subscript d represents the moderating effects of sex on the associations between precollege IPT and each relationship characteristic. Lastly, the pathways denoted by subscripts e and f represent the moderating effects of sex on the lagged and concurrent associations between IPT and each relationship characteristic, respectively. Although represented as one model, a parallel series of models was run for each relationship characteristic (relationship status, relationship satisfaction, partner alcohol use) with p-value thresholds of < .05 for each model because each characteristic represents a unique construct. College-onset IPT and all three relationship characteristics were treated as time-varying variables in these analyses (denoted by the subscripts ij), while sex and precollege IPT were treated as time-invariant variables (denoted by the subscript i).

We first fit generalized estimating equation (GEE) models with a logit link function and autoregressive (AR1) correlation structure using the “geepack” package (Højsgaard et al., 2005) in R (R Core Team, 2014) to estimate the main effects of precollege IPT (pathway a), lagged college-onset IPT (pathway b), and concurrent college-onset IPT (pathway c) on relationship status. Next, we fit linear mixed models with restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML) and autoregressive (AR1) correlation structure using the “nlme” package (Pinheiro et al., 2018) in R (R Core Team, 2014) to estimate the main effects of precollege IPT (pathway a), lagged college-onset IPT (pathway b), and concurrent college-onset IPT (pathway c) on relationship satisfaction and partner alcohol use. Random effects of intercept were incorporated to account for clustering within individuals. Lastly, to examine whether any of these associations varied in a sex-specific manner, we fit GEE and linear mixed models to estimate the two-way interactions between sex, precollege IPT (pathway d), lagged college-onset IPT (pathway e), and concurrent college-onset IPT (pathway f) to predict relationship status, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use.

Effect sizes are reported as odds ratios (ORs) converted to percentages for the GEE models and as marginal R2 for the unique variance accounted for by predictors and interaction terms in the linear mixed models. College-onset IPT and all three relationship characteristics were treated as time-varying variables in these analyses, while precollege IPT was a time-invariant variable. Cohort, age, and race/ethnicity were included as time-invariant covariates, and time in school was included as a time-varying covariate in these analyses. Sex was treated as time-invariant when included as a covariate and as a moderator.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 contains means and standard deviations for all continuous variables, as well as frequencies and percentages for all categorical variables. Less than half of all respondents were in a committed relationship at each assessment, but the percentage of students in relationships increased between freshman and senior year (39.4% to 47.0%). Across all assessments, the majority of respondents in a committed relationship were dating one person exclusively (> 93.7%), with relatively few (< 2.7%) who were engaged or married. Among those not in a committed relationship, the majority of respondents were not dating (> 87.8%), with relatively few who were dating several people (< 12.1%) or married but separated (< 0.12%). Approximately 38.2% of respondents reported a history of precollege IPT, and college-onset IPT ranged from 17.7% to 20.7% across assessments. Zero-order correlations for key study variables are shown in Table 2. Representativeness analyses comparing those included in the analytic sample to those excluded from the analytic sample suggested small but significant differences with respect to age, sex, and prevalence of IPT. Participants included in the analytic samples were significantly more likely to be younger, female, and have higher rates of precollege or college-onset IPT than those excluded from the analytic samples. All of these differences were of small effect as measured by Cohen’s d (all < .26; see Supplemental Information).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages by year for all continuous and categorical variables.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Overall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Age | 18.50 | 0.43 | 19.95 | 0.52 | 20.95 | 0.52 | 21.97 | 0.53 | 20.34 | 0.50 |

| Relationship Satisfaction | 6.39 | 1.07 | 6.20 | 1.09 | 6.17 | 1.13 | 6.16 | 1.16 | 6.25 | 1.11 |

| Partner Alcohol Use | 3.85 | 1.52 | 4.06 | 1.44 | 4.22 | 1.46 | 4.35 | 1.47 | 4.08 | 1.48 |

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | |||||||

| Variable | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Exposed to Precollege IPT | 2,895 | 38.22 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Exposed to College-Onset IPT | 1,391 | 18.94 | 963 | 20.71 | 651 | 17.66 | 450 | 19.34 | ||

| In a Committed Relationship | 2,190 | 39.44 | 1,982 | 41.90 | 1,713 | 45.70 | 1,113 | 46.98 | ||

| Dating One Person Exclusively | 2,123 | 1,926 | 1,640 | 1,043 | ||||||

Note. IPT = Interpersonal trauma; M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation. N = Frequency of respondents who positively endorsed that variable. % = Percentage of respondents who positively endorsed that variable. Means and standard deviations were calculated using longitudinal data, and frequencies and percentages were calculated using cross-sectional data.

Table 2.

Zero-order correlations between key study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Time | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Cohort | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Race/Ethnicity | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 4. Sex | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 5. Age | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 6. Precollege IPT | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 7. Concurrent College-Onset IPT | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 8. Lagged College-Onset IPT | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 9. Concurrent Relationship Status | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 1.00 | |||||

| 10. Lagged Relationship Status | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.50 | 1.00 | ||||

| 11. Concurrent Relationship Satisfaction | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.16 | −0.11 | - | 0.07 | 1.00 | |||

| 12. Lagged Relationship Satisfaction | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.18 | - | 0.39 | 1.00 | ||

| 13. Concurrent Partner Alcohol Use | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.14 | - | −0.09 | −0.15 | −0.07 | 1.00 | |

| 14. Lagged Partner Alcohol Use | 0.10 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.15 | −0.05 | - | −0.08 | −0.16 | 0.58 | 1.00 |

Note. IPT = interpersonal trauma. Bold type indicates p < .05. Bold italic type indicates p < .01.

Associations between IPT and Relationship Characteristics

Table 3 shows the parameter estimates from GEE models examining the main effects of precollege, concurrent college-onset, and lagged college-onset IPT exposure on relationship status (model 1) and the two-way interaction between sex and IPT exposure to predict relationship status (model 2). IPT exposure emerged as a significant main effect. Individuals who reported precollege IPT were approximately 39% more likely (OR = 1.39; 95% CI [1.13, 1.70]) to be in a relationship during college compared to those without a history of precollege IPT. In contrast, individuals who experienced concurrent college-onset IPT were 27% less likely (OR = 0.73; 95% CI [0.60, 0.89]) to be in a relationship than those without concurrent college-onset IPT, when controlling for the effects of lagged IPT. Finally, there was not a significant effect of lagged college-onset IPT on relationship status, meaning that experiencing college-onset IPT was not associated with relationship status the following year. There was no evidence that the associations between IPT and relationship status use varied in a sex-specific manner (all ps > .070).

Table 3.

Associations between precollege IPT, college-onset IPT exposure, sex, and relationship status.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | Sex Effects | |||

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.77 | [0.00, 121.51] | 0.88 | [0.01, 140.12] |

| Time | 1.10 | [1.03, 1.18] | 1.10 | [1.03, 1.18] |

| Cohort | ||||

| Cohort 2 | 0.98 | [0.77, 1.24] | 0.97 | [0.77, 1.23] |

| Cohort 3 | 1.03 | [0.82, 1.30] | 1.02 | [0.81, 1.29] |

| Cohort 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Race/Ethnicity (0 = White) | ||||

| African American/Black | 0.58 | [0.45, 0.75] | 0.58 | [0.45, 0.74] |

| Asian | 0.65 | [0.50, 0.84] | 0.65 | [0.50, 0.84] |

| More than one race | 1.26 | [0.85, 1.88] | 1.28 | [0.85, 1.91] |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.28 | [0.81, 2.03] | 1.27 | [0.80, 2.02] |

| Other race/ethnicity | 1.25 | [0.62, 2.50] | 1.26 | [0.64, 2.50] |

| Sex (0 = Male) | 1.46 | [1.17, 1.80] | 1.41 | [1.08, 1.85] |

| Age | 0.98 | [0.75, 1.29] | 0.98 | [0.74, 1.28] |

| Precollege IPT | 1.39 | [1.13, 1.70] | 1.16 | [0.79, 1.69] |

| Concurrent College-Onset IPT | 0.73 | [0.60, 0.89] | 1.01 | [0.68, 1.55] |

| Lagged College-Onset IPT | 1.01 | [0.84, 1.22] | 1.03 | [0.68, 1.48] |

| Sex*Precollege IPT | - | - | 1.29 | [0.83, 2.02] |

| Sex*Concurrent College-Onset IPT | - | - | 0.66 | [0.42, 1.03] |

| Sex*Lagged College-Onset IPT | - | - | 0.98 | [0.62, 1.55] |

| Observations | 3,396 | 3,396 | ||

Note. IPT = interpersonal trauma. Bold type indicates p < .05. Bold italic type indicates p < .01.

Table 4 contains the parameter estimates from the linear mixed models examining the main effects of precollege IPT, concurrent college-onset IPT, and lagged college-onset IPT exposure on relationship satisfaction (model 1) and the two-way interaction between sex and IPT exposure to predict relationship satisfaction (model 2). Individuals exposed to precollege IPT reported lower relationship satisfaction compared to those without IPT exposure, with precollege IPT accounting for 0.81% of the variance in relationship satisfaction. Individuals exposed to concurrent college-onset IPT reported lower relationship satisfaction than those without concurrent college-onset IPT, accounting for 1.17% of the variance in relationship satisfaction. Furthermore, there was a lagged effect of college-onset IPT, such that those with college-onset IPT (compared to those without) reported lower relationship satisfaction the following year. Lagged college-onset IPT accounted for 0.99% of the variance in relationship satisfaction. There was no evidence to suggest that the associations between IPT and relationship satisfaction varied in a sex-specific manner (all ps > .524).

Table 4.

Associations between precollege IPT, college-onset IPT exposure, sex, and relationship satisfaction.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | Sex Effects | |||

| Predictors | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 1.79 | [−0.20, 3.78] | 1.81 | [−0.18, 3.81] |

| Time | −0.04 | [−0.08, 0.01] | −0.04 | [−0.08, 0.01] |

| Cohort | ||||

| Cohort 2 | −0.19 | [−0.30, −0.08] | −0.19 | [−0.30, −0.08] |

| Cohort 3 | −0.21 | [−0.32, −0.10] | −0.21 | [−0.32, −0.10] |

| Cohort 4 | −0.24 | [−0.37, −0.11] | −0.24 | [−0.37, −0.11] |

| Race/Ethnicity (0 = White) | ||||

| African American/Black | −0.26 | [−0.37, −0.14] | −0.25 | [−0.37, −0.14] |

| Asian | −0.04 | [−0.16, 0.08] | −0.04 | [−0.15, 0.08] |

| More than one race | −0.12 | [−0.29, 0.05] | −0.12 | [−0.29, 0.06] |

| Hispanic/Latino | −0.03 | [−0.20, 0.14] | −0.03 | [−0.20, 0.15] |

| Other race/ethnicity | −0.00 | [−0.35, 0.35] | −0.00 | [−0.36, 0.35] |

| Sex (0 = Male) | 0.06 | [−0.04, 0.15] | 0.06 | [−0.06, 0.18] |

| Age | −0.08 | [−0.18, 0.03] | −0.08 | [−0.19, 0.03] |

| Precollege IPT | −0.16 | [−0.25, −0.07] | −0.16 | [−0.34, 0.02] |

| Concurrent College-Onset IPT | −0.31 | [−0.41, −0.21] | −0.36 | [−0.59, −0.13] |

| Lagged College-Onset IPT | −0.11 | [−0.21, −0.02] | −0.05 | [−0.27, 0.17] |

| Sex*Precollege IPT | - | - | 0.00 | [−0.21, 0.21] |

| Sex*Concurrent College-Onset IPT | - | - | 0.06 | [−0.19, 0.32] |

| Sex*Lagged College-Onset IPT | - | - | −0.08 | [−0.32, 0.17] |

| Observations | 2,637 | 2,637 | ||

Note. IPT = interpersonal trauma. Bold type indicates p < .05. Bold italic type indicates p < .01. Relationship satisfaction was standardized.

Table 5 contains the parameter estimates from the linear mixed models examining the main effects of precollege, concurrent college-onset, and lagged college-onset IPT exposure on partner alcohol use (model 1) and the two-way interaction between sex and IPT exposure to predict partner alcohol use (model 2). Individuals with concurrent college-onset IPT reported higher partner alcohol use compared to those without concurrent college-onset IPT, accounting for 1.12% of the variance in partner alcohol use. There was also a lagged effect of college-onset IPT, such that those with college-onset IPT (compared to those without) reported higher partner alcohol use the following year. Lagged college-onset IPT accounted for 0.09% of the variance in partner alcohol use. There was no evidence that precollege IPT exposure was associated with partner alcohol use (p = .193), or that the associations between IPT and partner alcohol use varied in a sex-specific manner (all ps > .105).

Table 5.

Associations between precollege IPT, college-onset IPT exposure, sex, and partner alcohol use.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | Sex Effects | |||

| Predictors | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 4.00 | [−2.78, 1.14] | 3.83 | [0.95, 6.70] |

| Time | 0.14 | [0.03, 0.10] | 0.14 | [0.09, 0.20] |

| Cohort | ||||

| Cohort 2 | 0.03 | [−0.10, 0.12] | 0.04 | [−0.13, 0.20] |

| Cohort 3 | 0.08 | [−0.10, 0.12] | 0.09 | [−0.07, 0.25] |

| Cohort 4 | −0.03 | [−0.18, 0.07] | −0.02 | [−0.20, 0.16] |

| Race/Ethnicity (0 = White) | ||||

| African American/Black | −0.40 | [−0.41, −0.19] | −0.40 | [−0.56, −0.24] |

| Asian | −0.44 | [−0.46, −0.23] | −0.45 | [−0.62, −0.28] |

| More than one race | −0.15 | [−0.25, 0.09] | −0.15 | [−0.40, 0.10] |

| Hispanic/Latino | −0.21 | [−0.32, 0.02] | −0.21 | [−0.46, 0.03] |

| Other race/ethnicity | −0.34 | [−0.53, 0.15] | −0.35 | [−0.84, 0.15] |

| Sex (0 = Male) | 0.19 | [0.08, 0.26] | 0.31 | [0.13, 0.48] |

| Age | −0.01 | [−0.07, 0.14] | −0.01 | [−0.16, 0.15] |

| Precollege IPT | 0.08 | [−0.04, 0.21] | 0.25 | [−0.01, 0.50] |

| Concurrent College-Onset IPT | 0.33 | [0.20, 0.45] | 0.54 | [0.26, 0.82] |

| Lagged College-Onset IPT | 0.26 | [0.14, 0.38] | 0.30 | [0.02, 0.57] |

| Sex*Precollege IPT | - | - | −0.22 | [−0.51, 0.05] |

| Sex*Concurrent College-Onset IPT | - | - | −0.26 | [−0.57, 0.05] |

| Sex*Lagged College-Onset IPT | - | - | −0.04 | [−0.34, 0.27] |

| Observations | 3,066 | 3,066 | ||

Note. IPT = interpersonal trauma. Bold type indicates p < .05. Bold italic type indicates p < .01. Partner alcohol use was standardized.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of emerging adult college students, we examined 1) whether precollege IPT predicted relationship status, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use; 2) whether college-onset IPT had concurrent or lagged associations with those relationship characteristics; and 3) whether these associations varied in a sex-specific manner. We observed significant effects of precollege and college-onset IPT on relationship status and relationship satisfaction, and significant effects of college-onset IPT on partner alcohol use. Despite previous findings that females experience more adverse outcomes following trauma exposure compared to males, such as higher rates of trauma-related distress and anxiety (Overstreet et al., 2017) and greater risk for PTSD (Breslau et al., 1999; Kessler, 1995; Stevens et al., 2018), we did not observe any sex-specific associations between IPT and relationship characteristics. We discuss each of our key findings in turn.

Relationship Status

Consistent with prior research on the associations between broad trauma exposure and relationships among adults (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Taft et al., 2011), we found that IPT exposure was significantly associated with the formation of romantic relationships among college students. Interestingly, the direction of association varied depending on the developmental timing of IPT exposure, which we speculate may reflect a number of potential processes based on complementary lines of evidence. We found that individuals exposed to precollege IPT were more likely than those not exposed to precollege IPT to be in a relationship. This effect was unexpected in view of previous research suggesting that trauma which occurs earlier in development leads to long-term maladaptive changes in affective, relational, and self-regulatory functioning (Cloitre et al., 2019; van der Kolk et al., 2005) and is associated with insecure adult attachment styles (i.e., anxious and avoidant; Mickelson, Kessler, & Shaver, 1997; Riggs, Cusimano, & Benson, 2011), all of which may jeopardize one’s ability to develop self-esteem and self-control (Crittenden & Ainsworth, 1989; Riggs et al., 2011). Considering these lines of research in tandem, however, we posit the possibility that individuals exposed to precollege IPT may be more likely to enter into relationships, relative to staying single, because they fear being alone, consistent with previous research that romantic partners can help with one’s own self-regulation (Riggs et al., 2011).

In contrast, and consistent with our expectations, those exposed to concurrent college-onset IPT were more likely to be single compared to those who did not experience concurrent college-onset IPT. The ways that individuals cope with stressful life events, such as IPT exposure, vary based on their appraisal of the event and the psychosocial resources available (Moos, 1992). We thus speculate that individuals exposed to concurrent college-onset IPT may be less likely to form romantic partnerships because they are instead focused on coping with the recent traumatic event and have fewer resources to devote to forming a relationship. This is consistent with previous research that suggests that exposure to stressful experiences may impact individuals’ ability to form protective relationships in the first place (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Taft et al., 2011). Importantly, however, this pattern of effects was time-delimited, as there was no lagged effect of college-onset IPT on individual’s relationship status the following year.2

Relationship Satisfaction and Partner Alcohol Use

For college students in relationships, our findings suggest IPT exposure can influence the perceived characteristics of their romantic relationships. Individuals exposed to precollege and concurrent college-onset IPT were more likely to report lower relationship satisfaction3, and those exposed to college-onset IPT also reported higher partner alcohol use. Moreover, college-onset IPT was associated relationship satisfaction and partner alcohol use the following year, suggesting a protracted interplay rather than a time-delimited one. The association between IPT and characteristics of romantic relationships is consistent with previous studies conducted with adults which suggest that individuals who experienced a traumatic event become less connected, less satisfied, and more negative with their partners (Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Marshall & Kuijer, 2017; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009; Robles et al., 2014; Whisman, 2014). Additionally, previous research indicates that individuals from high-risk backgrounds, such as those with a history of trauma exposure, are more likely to choose deviant partners with higher levels of substance use (Quinton et al., 1993; Zoccolillo et al., 1992). Taken together, this suggests that IPT-exposed college students who are in committed relationships are more likely to be in relationships that are not necessarily healthy or protective, and similar to the long-term consequences of childhood trauma (Norman et al., 2012), this pattern of effects endures over time.

Implications

As relationship problems are one of the most common reasons that college students seek counseling services (Mistler et al., 2012), clinicians working with this population should be aware that a history of IPT can modestly influence key relationship characteristics. Clinicians should also understand and consider the implications of being in a relationship following precollege IPT, as it may not always be adaptive if the relationship is not satisfying and involves a deviant romantic partner (Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007; Robles et al., 2014). Clinicians can also use this information educate their clients on the range of potential consequences they may experience following IPT. For example, clinicians can educate clients on the potential long-term effects of precollege IPT as it relates to social relationships, including emotional regulation, attachment formation, and stress responses (Overstreet et al., 2017). They can also teach clients about the potential effects of college-onset IPT, including challenges it poses to forming relationships with prosocial partners, and healthy ways to cope with such challenges (Berenz et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2021). In taking these actions, clinicians can help minimize relationship dissatisfaction, while promoting healthy methods of self-regulation.

Understanding the implications of IPT exposure on romantic relationship formation and perceptions is also of clinical significance in light of substantial research documenting the moderating effect of relationships on health outcomes (Cho et al., 2020; Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Rauer et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2021). Of particular relevance, in our prior work, we found that involvement in romantic relationships buffers against the effects of precollege IPT exposure on alcohol use, while being involved with a partner higher partner alcohol use exacerbated the effects of college-onset trauma on alcohol use (Smith et al., 2021). Considered with other research suggesting that individuals exposed to trauma are at risk for problematic alcohol use (Berenz et al., 2016; Overstreet et al., 2017), knowledge about individuals’ relationship status and the characteristics of their relationships is critical.

More broadly, findings from the present study can contribute to our understanding of the associations between IPT exposure and the navigation of salient psychosocial developmental tasks. As noted, a key developmental task in emerging adulthood is the formation and exploration of romantic relationships (Arnett, 2004; Shulman & Connolly, 2013; Umberson et al., 2010). Involvement in romantic relationships during college is important for normative development because it provides opportunities to learn and improve one’s social and emotional competence, skills that are necessary for future successful romantic relationships (Rauer et al., 2013; Seiffge-Krenke, 2003). In view of evidence that IPT exposure shapes social and emotional competence in important ways earlier in development (Cicchetti & Doyle, 2016; Kim & Cicchetti, 2003), it also follows that IPT is also associated with individuals’ likelihood of forming and maintaining healthy, satisfying romantic relationships in adulthood. In sum, findings from the present study can inform our understanding of impediments to normative development, including those that contribute to developmental psychopathology. Future research can expand on this work to provide additional insight into these associations.

Limitations

Results from the present study should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, data were collected via self-report and may be subject to self-presentation biases. Second, we did not account for IPT severity or post-traumatic stress symptoms because we were unable to directly link individuals’ symptoms to their IPT exposure. Third, there were high levels of attrition in later waves of the sample. To determine the impact of this on our sample composition, we conducted a series of representativeness analyses. Our analytic samples were younger, comprised of more females, and were more likely to report IPT exposure than those excluded from our analytic samples; however, these differences were all of small effect (see Supporting Information). Lastly, we only studied IPT among college students at a large, urban university. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to other types of traumatic events or to a broader emerging adult population.

The present study should also be considered in the context of the small observed effect sizes. We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to determine whether our small effect sizes were attributable to the way our variables were measured. First, in light of previous research suggesting that cumulative IPT exposure confers greater risk than a single traumatic event (Cloitre et al., 2009), we ran a set of sensitivity analyses in which we examined whether our pattern of results changed when using cumulative IPT exposure as our predictor. Next, to evaluate the possibility that relationship length and relationship stability might change our observed patterns of results, we ran two sets of sensitivity analyses in which we included relationship length and past-year break-up as time-varying covariates. Across all sets of sensitivity analyses, we largely observed the same pattern of effects (see Supporting Information). This suggests that the small observed effect sizes are likely not due to the way that our variables were measured. Further, despite the small effect sizes, our findings shed insight on the factors that influence the formation of romantic relationships and the characteristics of those relationships.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The present study address key gaps in the scientific understanding of whether and how IPT exposure influences romantic relationship status, relationship satisfaction, and partner alcohol use among emerging adult college students, and whether these effects persist over time. Results from the present study suggest that IPT exposure, and the developmental timing of IPT, may affect college students’ relationship status. Those exposed to precollege IPT were more likely to be in a relationship, while those exposed to college-onset IPT were less likely to be in a relationship. Findings also suggest that IPT affects their ability to form satisfying relationships with prosocial partners. Future research is needed to better understand whether IPT exposure influences other important relationship characteristics (e.g., perceptions of partner commitment, future orientation as it pertains to their romantic relationships). Additionally, future research (e.g., using ecological momentary assessment methods) is needed to gain deeper insight into individuals’ post-traumatic stress symptoms, interactions with their partners, and general perceptions of their relationships in real time. Better understanding and consideration of the interplay between IPT exposure and romantic relationships is critical, as it represents a potentially useful component of treatment and the promotion of wellbeing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Spit for Science has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA017828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, P50 AA022537, and K01AA024152 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. This research was also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54DA036105 and the Center for Tobacco Products of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Rebecca Smith was supported by 1F31AA028720-01A1 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the FDA. Data from this study are available to qualified researchers via dbGaP (phs001754.v2.p1). We would like to thank the Spit for Science participants for making this study a success, as well as the many University faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project.

APPENDIX

The Spit for Science Working Group: Director: Danielle M. Dick, Co-Director: Ananda Amstadter. Registry management: Emily Lilley, Renolda Gelzinis, Anne Morris. Data cleaning and management: Katie Bountress, Amy E. Adkins, Nathaniel Thomas, Zoe Neale, Kimberly Pedersen, Thomas Bannard & Seung B. Cho. Data collection: Amy E. Adkins, Kimberly Pedersen, Peter Barr, Holly Byers, Erin C. Berenz, Erin Caraway, Seung B. Cho, James S. Clifford, Megan Cooke, Elizabeth Do, Alexis C. Edwards, Neeru Goyal, Laura M. Hack, Lisa J. Halberstadt, Sage Hawn, Sally Kuo, Emily Lasko, Jennifer Lend, Mackenzie Lind, Elizabeth Long, Alexandra Martelli, Jacquelyn L. Meyers, Kerry Mitchell, Ashlee Moore, Arden Moscati, Aashir Nasim, Zoe Neale, Jill Opalesky, Cassie Overstreet, A. Christian Pais, Kimberly Pedersen, Tarah Raldiris, Jessica Salvatore, Jeanne Savage, Rebecca Smith, David Sosnowski, Jinni Su, Nathaniel Thomas, Chloe Walker, Marcie Walsh, Teresa Willoughby, Madison Woodroof & Jia Yan. Genotypic data processing and cleaning: Cuie Sun, Brandon Wormley, Brien Riley, Fazil Aliev, Roseann Peterson & Bradley T. Webb.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Our second sample of individuals in a relationship at one or more time points is larger than our first sample in which relationship status was the outcome of interest. We used generalized estimating equation (GEE) models to assess the associations between IPT and relationship status, which requires complete information on all variables at all time points for cases to be included in the model. The linear mixed models used to assess the associations between IPT and relationship satisfaction and partner substance use does not have this stringent requirement.

To examine the possibility that relationship status had lagged effects on college-onset IPT, we ran a series of supplementary analyses. We observed no lagged effect of relationship status, supporting the present interpretation that college-onset IPT is likely to influence relationship status rather than the reverse.

To examine the possibility that relationship satisfaction had lagged effects on college-onset IPT, we ran a series of supplementary analyses. We observed no lagged effect of relationship satisfaction, supporting the present interpretation that college-onset IPT is likely to influence relationship satisfaction rather than the reverse.

References

- Arnett JJ (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam EG, Kessler RC, Mclaughlin KA, Ruscio AM, Shahly V, Stein DJ, Petukhova M, Hill E, Alonso J, Atwoli L, Bunting B, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-De-Almeida JM, De Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Huang Y, … Koenen KC (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343. 10.1017/S0033291715001981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenz EC, Cho SB, Overstreet C, Kendler K, Amstadter AB, & Dick DM (2016). Longitudinal investigation of interpersonal trauma exposure and alcohol use trajectories. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 67–73. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC, & Siegler IC (2011). Two versions of life: Emotionally negative and positive life events have different roles in the organization of life story and identity. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 11(5), 1190–1201. 10.1037/a0024940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Peterson EL, & Lucia VC (1999). Vulnerability to assaultive violence: Further specification of the sex difference in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 29(4), 813–821. 10.1017/S0033291799008612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, & Schultz LR (2008). A second look at prior trauma and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder effects of subsequent trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(4), 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SB, Smith RL, Bucholz K, Chan G, Edenberg HJ, Hesselbrock V, Kramer J, McCutcheon VV, Nurnberger J, Schuckit M, Zang Y, Dick DM, & Salvatore JE (2020). Using a developmental perspective to examine the moderating effects of marriage on heavy episodic drinking in a young adult sample enriched for risk. Development and Psychopathology, 1–10. 10.1017/S0954579420000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Doyle C (2016). Child maltreatment, attachment and psychopathology: Mediating relations. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 89–90. 10.1002/wps.20337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Handley ED (2019). Child maltreatment and the development of substance use and disorder. Neurobiology of Stress, 10, 100144–100144. PubMed. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.100144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Khan C, Mackintosh M-A, Garvert DW, Henn-Haase CM, Falvey EC, & Saito J (2019). Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ACES and physical and mental health. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(1), 82–89. 10.1037/tra0000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, Kolk B. van der, Pynoos R, Wang J, & Petkova E (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. 10.1002/jts.20444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM, & Ainsworth MDS (1989). Child maltreatment and attachment theory. In Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect (pp. 432–463). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511665707.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, Meyers J, Yan J, Cooke M, Clifford J, Goyal N, Halberstadt L, Ailstock K, Neale Z, Opalesky J, Hancock L, Donovan KK, Sun C, Riley B, & Kendler KS (2014). Spit for Science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics, 5. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman GS, Quas JA, & Ogle CM (2010). Child maltreatment and memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 325–351. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, & Lombardo TW (2004). Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment, 11(4), 330–341. 10.1177/1073191104269954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawn SE, Lind MJ, Conley A, Overstreet CM, Kendler KS, Dick DM, & Amstadter AB (2018). Effects of social support on the association between precollege sexual assault and college-onset victimization. Journal of American College Health, 1–9. 10.1080/07448481.2018.1431911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS, Dick A, & Hendrick C (1998). The Relationship Assessment Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(1), 137–142. 10.1177/0265407598151009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Højsgaard S ., Halekoh U, & Yan J (2005). The R Package geepack for Generalized Estimating Equations. Journal of Statistical Software, 15(2), 1–11. 10.18637/jss.v015.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BRK, & Bradbury TN (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34. 10.14515/monitoring.2016.1.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Jacobson K, Myers JM, & Eaves LJ (2008). A genetically informative developmental study of the relationship between conduct disorder and peer deviance in males. Psychological Medicine, 38(07). 10.1017/S0033291707001821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC (1995). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048. 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hasin DS (2011). Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: The epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology, 218(1), 1–17. 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Wilson SJ (2017). Lovesick: How couples’ relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 421–443. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. 10.1002/jts.21848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, & Cicchetti D (2003). Social self-efficacy and behavior problems in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(1),106–117. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassri D, Luyten P, Cohen G, & Shahar G (2016). The effect of childhood emotional maltreatment on romantic relationships in young adulthood: A double mediation model involving self-criticism and attachment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 8(4), 504–511. 10.1037/tra0000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, & Emmons KM (2006). Understanding health behavior change among couples: An interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science & Medicine, 62(6), 1369–1380. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP (2003). For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(7), 959–997. 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EM, & Kuijer RG (2017). Weathering the storm? The impact of trauma on romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 54–59. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy G, & Taylor A (1999). Avoidant/Ambivalent attachment style as a mediator between abusive childhood experiences and adult relationship difficulties. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(3), 465–477. 10.1111/1469-7610.00463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, & Cook JM (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, & Shaver PR (1997). Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(5), 1092–1106. 10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistler BJ, Reetz DR, Krylowicz B, & Barr V (2012). The Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors Annual Survey. 188. https://files.cmcglobal.com/Monograph_2012_AUCCCD_Public.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Molnar DS, Sadava SW, DeCourville NH, & Perrier CPK (2010). Attachment, motivations, and alcohol: Testing a dual-path model of high-risk drinking and adverse consequences in transitional clinical and student samples. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 42(1), 1–13. 10.1037/a0016759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Taft CT, & Fredman SJ (2009). Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 707–714. 10.1016/_j.cpr.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (1992). Stress and coping theory and evaluation research: An integrated perspective. Evaluation Review, 16(5), 534–553. 10.1177/0193841X9201600505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, & Vos T (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9(11), e1001349. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, & Siegler IC (2013). The impact of the developmental timing of trauma exposure on PTSD symptoms and psychosocial functioning among older adults. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2191–2200. 10.1037/a0031985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshri A, Kogan SM, Kwon JA, Wickrama KAS, Vanderbroek L, Palmer AA, & MacKillop J (2018). Impulsivity as a mechanism linking child abuse and neglect with substance use in adolescence and adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 30(2), 417–435. 10.1017/S0954579417000943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet C, Berenz EC, Kendler KS, Dick DM, & Amstadter AB (2017). Predictors and mental health outcomes of potentially traumatic event exposure. Psychiatry Research, 247, 296–304. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Quirk K, & Manthos M (2012). I get no respect: The relationship between betrayal trauma and romantic relationship functioning. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13(2), 175–189. 10.1080/15299732.2012.642760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin M, Vandeleur CL, Castelao E, Rothen S, Glaus J, Vollenweider P, & Preisig M (2014). Determinants of the development of post-traumatic stress disorder, in the general population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(3), 447–457. 10.1007/s00127-013-0762-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, & R Core Team. (2018). nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models (3.1-137) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Pickles A, Maughan B, & Rutter M (1993). Partners, peers, and pathways: Assortative pairing and continuities in conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 763–783. 10.1017/S0954579400006271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AK, & Bodenmann G (2009). The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(2), 105–115. 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer AJ, Pettit GS, Lansford JE, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2013). Romantic relationship patterns in young adulthood and their developmental antecedents. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2159–2171. 10.1037/a0031845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer AJ, Pettit GS, Samek DR, Lansford JE, Dodge KA, & Bates JE (2016). Romantic relationships and alcohol use: A long-term, developmental perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 28(03), 773–789. 10.1017/S0954579416000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Rhule-Louie DM, & McMahon RJ (2007). Problem behavior and romantic relationships: Assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10(1), 53–100. 10.1007/s10567-006-0016-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs SA, Cusimano AM, & Benson KM (2011). Childhood emotional abuse and attachment processes in the dyadic adjustment of dating couples. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(1), 126–138. 10.1037/a0021319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, & McGinn MM (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1). 10.1037/a0031859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs-Ericsson N, Medley AN, Kendall-Tackett K, & Taylor J (2011). Childhood abuse and current health problems among older adults: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Psychology of Violence, 1(2), 106–120. 10.1037/a0023139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I (2003). Testing theories of romantic development from adolescence to young adulthood: Evidence of a developmental sequence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6), 519–531. 10.1080/01650250344000145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Dick D, Amstadter A, Thomas N, Spit for Science Working Group, & Salvatore J (2021). A longitudinal study of the moderating effects of romantic relationships on the associations between alcohol use and trauma in college students Addiction, 1–11. 10.1111/add.15490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, & Connolly J (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39. 10.1177/2167696812467330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JS, van Rooij SJH, & Jovanovic T (2018). Developmental contributors to trauma response: The importance of sensitive periods, early environment, and sex differences. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 38, 1–22. 10.1007/7854_2016_38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Watkins LE, Stafford J, Street AE, & Monson CM (2011). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 22–33. 10.1037/a0022196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Crosnoe R, & Reczek C (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 139–157. 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, Roth S, Pelcovitz D, Sunday S, & Spinazzola J (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389–399. 10.1002/jts.20047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA (2014). Dyadic perspectives on trauma and marital quality. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(3), 207–215. 10.1037/a0036143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Reitzeljaffe D, & Lefebvre L (1998). Factors associated with abusive relationships among maltreated and nonmaltreated youth. Development and Psychopathology, 10(1), 61–85. 10.1017/S0954579498001345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, & Kandel D (1993). Marital homophily on illicit drug use among young adults: Assortative mating or marital influence? Social Forces, 72(2), 505–528. 10.2307/2579859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir O (2021). Childhood Maltreatment and Relationship Quality: A Review of Type of Abuse and Mediating and Protective Factors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1–14. 10.1177/1524838021998319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccolillo M, Pickles A, Quinton D, & Rutter M (1992). The outcome of childhood conduct disorder: Implications for defining adult personality disorder and conduct disorder. Psychological Medicine, 22(4), 971–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.