Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to compare the suture versus sutureless surgery in impacted mandibular third molar and to evaluate the morbidity and complications associated with each technique.

Materials and Methods

A total of 50 patients with asymptomatic impacted mandibular third molars were randomly divided into two groups of 25 patients each. Radiographs were taken to assess the angulation and degree of eruption in the third molar. A small modified Szmyd, V-shaped flap was raised in all cases, and teeth were extracted. In Group I—Suture group (suture was used to close the flap), and in Group II—Sutureless group (no suture used to close the flap). The post-operative pain, swelling, trismus, haemorrhage, periodontal pocket, and alveolar osteitis were evaluated at 24 h, 48 h, 5th days, 7th days, and 2 weeks after surgery. The statistical analysis was done using the Chi-square "t" test and Independent Samples "t" test.

Observations and Results

Pain, swelling, and trismus were found to be significantly reduced especially in the immediate post-operative period in the sutureless group as compared to the suture group (p < 0.001). There were no incidences of intra-operative and post-operative haemorrhage in any case. Follow-up of all the patients showed that there was no difference in periodontal sequelae and alveolar osteitis

Conclusions

Sutureless surgery with small flap was found to be less invasive, time-saving, and also a cost-effective method. This technique significantly reduced the early crucial phase of patient discomfort and demonstrates good results.

Keywords: Mandibular third molar, Impaction, Modified Szmyd incision, Sutureless surgery

Introduction

Mandibular third molars have the greatest (42.37%) incidence of impaction [1], and their surgical removal is one of the most frequently performed procedure [2]. The surgical approach for the removal of lower third molars is different as the reflection of soft tissues and the amount of bone removed is substantially greater than other surgical tooth extractions [3]. Different methods have been formulated to carry out the removal of lower third molars, with common objectives of adequate visibility, satisfactory wound healing, decreased surgical morbidity, and patient comfort. Various complications associated with removal of lower third molars from early post-operative period to the late post-operative period include pain, swelling, trismus, alveolar osteitis, etc.

In third molar surgery, mucoperiosteal flap closure is one of the factors influencing the post-operative sequelae. There have been different opinions regarding primary and secondary closure techniques. Some authors have recommended the primary closure in third molar flap because they follow the basic surgical principles [4]. Primary closure technique is more popular because it limits the size of the wound, helps in the maintenance of clot, reduces the chances of contamination and infection, though it does not facilitate drainage. Whereas, other authors have recommended healing by secondary intention to facilitate drainage and irrigation from the bony socket.

Instead of Terence Wards flap, a modified Szmyd flap has been used in this study which is smaller and leaves a comparatively smaller defect. This allows passive falling of flap into a natural position and leaving the socket slightly open during repositioning of flap. A small flap left open facilitates drainage and irrigation, thus reducing the incidence of post-operative oedema, trismus, alveolar osteitis, pain, and periodontal sequelae.

Material and Methods

Fifty patients with asymptomatic impacted mandibular third molars were randomly selected from the Out-Patient Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. These patients were randomly divided into groups of 25 patients each.

Group 1: Suturing was done for primary closure following surgical removal of mandibular third molars.

Group 2: No suturing was done after the surgical removal of mandibular third molars.

Inclusion criteria: 1. Age group of 18–48 years irrespective of sex, caste, religion, and socioeconomic status. 2. Asymptomatic mandibular third molars.

Exclusion criteria: 1. Contraindication for local anaesthesia or surgery. 2. Medically compromised patients. 3. Chronic smokers. 4. Symptomatic third molars (pericoronitis or infected).

The complete history of all the patients was taken, and a thorough clinical examination was done to rule out any systemic problem. Local intraoral clinical examination was done to examine the mucous membrane and the third molar region which was to be operated. An intraoral periapical radiograph or orthopantomogram for impacted mandibular third molar was taken for radiographic evaluation. Each patient was informed about the procedure and purpose of the study in detail and consent was obtained. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the institution.

Patients were asked to rinse the mouth thoroughly with 0.2% chlorhexidine and normal saline in equal proportions. Extraoral and intraoral preparation was done with 5% betadine. Draping of the patient was done with sterile drapes. Intraorally inferior alveolar, lingual, and long buccal nerve blocks were given on the side to be operated, injecting a 2% solution of lignocaine hydrochloride with 1:100,000 adrenaline.

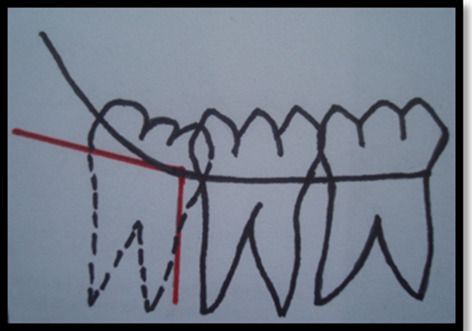

A modified Szmyd, i.e. a small ‘V’-shaped incision was given with the bard parker handle no.3 and a no.15 blade. The incision starts at the distobuccal line angle of the second molar and extended down to the mucogingival junction. Other vertical limbs followed the external oblique ridge as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Modified Szmyd Incision: V-shaped incision with one point at distobuccal line angle of second molar. One vertical limb along the external oblique ridge and other down to the mucogingival junction

Surgical procedures in Group I and Group II are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Fig. 2.

Modified Szmyd incision was used in Group I and Group II

Fig. 3.

Modified Szmyd flap reflection and Moore/Gillbe collar technique was used in Group I and Group II

Fig. 4.

Suturing was done with 3–0 Mersilk suture in Group I

Fig. 5.

Flap repositioning without suture placement was done in Group II

Immediate post-operative follow-up after 24 h was carried out. Patients were recalled thereafter according to the study protocol, and the parameters were recorded on subsequent days.

Observations and Results

The present study was carried out in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with an objective to compare the flap closure with suture versus sutureless surgery with modified Szmyd flap for surgical removal of impacted lower third molars and to assess the morbidity associated with each technique in terms of haemorrhage, pain, swelling, trismus, alveolar osteitis, and periodontal pocket depth.

A total of 50 patients were enrolled in the present study. Based on the technique used for surgery, they were divided into two groups. Twenty-five patients in Group I were operated using sutures for flap closure after mandibular third molars impaction, while in Group II were operated without sutures, i.e. sutureless procedure

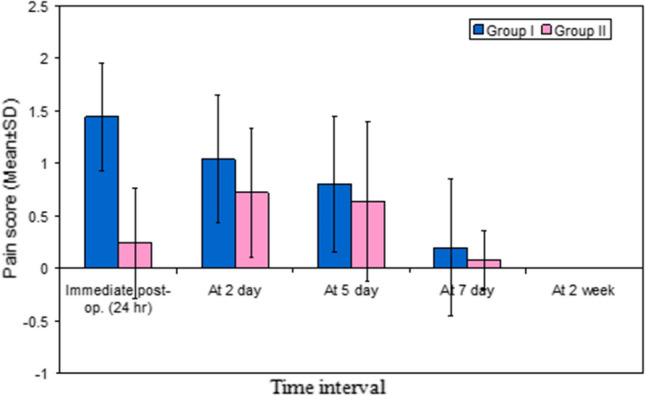

Pain—Post-operative pain was evaluated using the Verbal Pain Scale (VPS) at the time intervals of immediate post-operative, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth days as shown in Table 1.

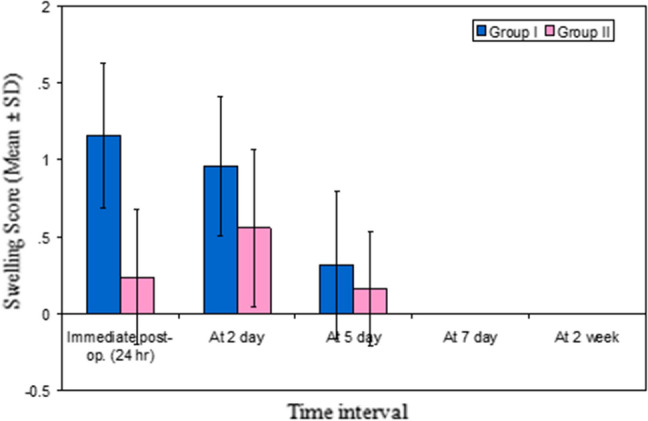

Swelling—Post-operative swelling was evaluated using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) at the time intervals of immediate post-operative, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth days, referring to predefined values as given in Table 2.

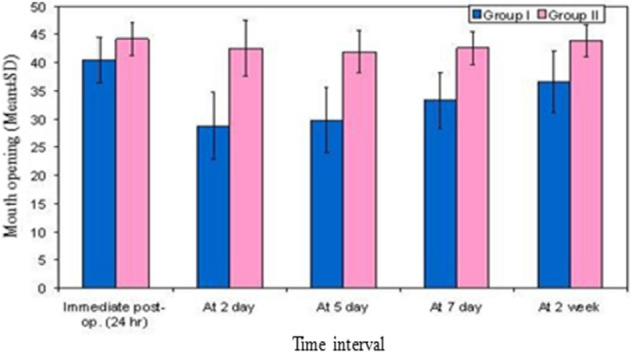

Post-operative mouth opening was measured by inter-incisal distance in millimetres between the maxillary and mandibular central incisors at maximum mouth opening. The difference in the pre-operative and post-operative values will be recorded at the time intervals of immediate post-operative, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth days as given in Table 3.

-

Post-operative periodontal pocket distal to the second molar was evaluated on the distal surface of the second molar post-operatively at the time intervals of immediate post-operative, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth days as given in Table 4.

All measurements were carried out by using William’s periodontal probe. The following reference values were given to patients corresponding to periodontal pocket probing depth.

0—Absent (Periodontal pocket probing depth <4 mm)

1—Present (Periodontal pocket probing depth >4 mm)

Haemorrhage—No haemorrhage was observed in any case in either of the two groups post-operatively at any time interval.

Alveolar osteitis observed based on severe pain as per verbal pain scale, loss of blood clot in the socket, and halitosis post-operatively at the time intervals of second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth days.

Table 1.

Evaluation of pain at different follow-up intervals

| S. no | Time interval follow-up | Group I | Group II | Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Z | p | ||

| 1 | Immediate post-op. (24 h) | 1.44 | 0.51 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 5.494 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | At 2 days | 1.04 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 1.809 | 0.070 |

| 3 | At 5 days | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 1.013 | 0.311 |

| 4 | At 7 days | 0.20 | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.504 | 0.615 |

| 5 | At 2 weeks | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Table 2.

Evaluation of swelling at different follow-up intervals

| S. no | Time interval follow-up | Group I | Group II | Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Z | p | ||

| 1 | Immediate post-op. (24 h) | 1.16 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 5.173 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | At 2 days | 0.96 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 2.715 | 0.007 |

| 3 | At 5 days | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 1.311 | 0.190 |

| 4 | At 7 days | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | At 2 weeks | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 1 |

Table 3.

Evaluation of mouth opening at different follow-up intervals

| S.no | Time interval follow-up | Group I | Group II | Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | ||

| 1 | Immediate post-op. (24 h) | 40.52 | 4.01 | 44.24 | 2.93 | 3.743 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | At 2 days | 28.80 | 5.99 | 42.56 | 4.93 | 8.875 | < 0.001 |

| 3 | At 5 days | 29.80 | 5.78 | 41.96 | 3.78 | 8.803 | < 0.001 |

| 4 | At 7 days | 33.32 | 5.00 | 42.60 | 2.87 | 6.040 | < 0.001 |

| 5 | At 2 weeks | 36.60 | 5.39 | 43.96 | 2.85 | 3.743 | < 0.001 |

Table 4.

Evaluation of periodontal pocket at different follow-up intervals

| S. no | Time interval follow-up | Group I | Group II | Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | χ2 | p | ||

| 1 | Immediate post-op. (24 h) | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 2.000 | 0.157 |

| 2 | At 2 days | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 2.000 | 0.157 |

| 3 | At 5 days | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 2.000 | 0.157 |

| 4 | At 7 days | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 2.000 | 0.157 |

| 5 | At 2 weeks | 4 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 2.000 | 0.157 |

No evidence of alveolar osteitis was observed in any case in either of the two groups at any time interval.

Discussion

Removal of impacted mandibular third molars is a common dentoalveolar surgical procedure, which requires a sound understanding of surgical principles since the removal of impacted mandibular third molars involves the surgical manipulation and exposure of both hard and soft tissues to a relatively septic environment. The surgical removal of impacted third molars can be performed by different techniques, each with its own merits and demerits, aiming to reduce surgical morbidity and enhance patient comfort. The sequelae of removal of lower third molar surgery include pain, swelling, trismus, and complications like alveolar osteitis, pocket formation distal to the lower second molar, and inferior alveolar nerve paraesthesia.

Pain, being largely a subjective experience, was assessed in the present study by the Verbal Pain Scale (VPS) at the time intervals of the immediate post-operative, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth day. In Group I, the pain score was 1.44 in the immediate post-operative period, and in Group II, pain score was only 0.24, thus showing a statistically significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.001). At two days interval, the mean pain score in Group I was 1.04, while it was 0.72 in Group II. A fifth day, mean pain score in Group I decreased to 0.80, while it became 0.64 in Group II. On the seventh day, the mean pain score in Group I was 0.20, while it was 0.08 in Group II. At 2 weeks, there was no pain observed in either of the two groups. Though the mean pain score was lower in Group II at all time intervals, yet a statistically significant difference between the two groups was observed only at the immediate post-operative interval. At the second, fifth, and seventh day, mean pain score was not statistically significant between the two groups (Graph 1).

Graph 1.

Depicting the pain at different time points

These results are consistent with the study of Dubois et al. [5] who concluded that secondary closure minimizes pain in the immediate post-operative period, which is in support of the present study as the pain was minimum in the immediate post-operative period in the sutureless group. Madan et al. [6] concluded that, in cases of equal intra-operative difficulty, secondary closure of the surgical wound after removal of impacted third molars produces less post-operative pain than primary closure.

Third molar removal is a traumatic surgical procedure, in which pain is generated by the release of endogenous mediators, such as bradykinin, serotonine, and certain types of prostaglandins. In the secondary closure technique, the socket remains in communication with the oral cavity to facilitate irrigation and drainage of these inflammatory products, causing less post-operative pain after lower third molar surgery.

The swelling was assessed in the present study by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) given by Pasqualini et al. [7] which has been slightly modified. Swelling is graded as 0 (no swelling), 1 (mild swelling), 2 (moderate swelling), 3 (severe swelling), post-operatively at twenty-four hours, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth day. The mean value of post-operative swelling in Group I was 1.16 and in Group II was 0.24, showing statistically significant results in the immediate post-operative period (p < 0.001). A second day, mean swelling score in Group I, was to 0.96, while it was 0.56 in Group II. On a fifth day, the mean score in Group I further decreased to 0.32 and 0.16 in Group II. On the seventh day and two weeks post-operatively, there was no swelling observed in either of the two groups (Graph 2).

Graph 2.

Depicting the swelling at different time points

These results are consistent with the study of Dubois et al. [5] who concluded that secondary closure was found to minimize swelling in the immediate post-operative period, which supports the present study as the swelling was minimum in the immediate post-operative period in Group II. Saglam [8], Pasqualini et al. [7] and Danda et al. [9] also reported significantly lesser swelling with secondary closure. Removal of impacted lower third molars involves trauma to soft tissues and bone, which results in local oedema caused by the accumulation of exudate in interstitial tissue spaces by the release of various chemical mediators such as histamine, prostaglandins, cytokines, tissue necrosis factors, and platelet-derived growth factors. During secondary closure, the socket remains slightly open to facilitate irrigation and drainage of these inflammatory products which results in less post-operative swelling after impaction.

Post-operative mouth opening was measured as a difference in the interincisal distance in millimetres pre-operatively and post-operatively. It was calculated immediately post-operatively, at second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth day. Immediate post-operatively in Group I, mean trismus score was 40.52, while in Group II, it was 44.24 (t = 3.743, p < 0.001). A second day, the mean score in Group I was 28.80, while it was 42.56 in Group II (t = 8.875, p < 0.001). On a fifth day, the mean score in Group I was 29.80, while in Group II, it was 41.96 (t = 8.803, p < 0.001).On the seventh day, the mean score in Group I was 33.32 and in group II it was 42.60 (t = 6.040, p < 0.001). At 2 weeks, the mean value in group I was 36.60 and in group II it was 43.96 (t = 3.743, p < 0.001). Thus, at all time intervals in group II patients very highly significant lower trismus scores (p < 0.001) were observed as compared to group I (Graph 3).

Graph 3.

Depicting the mouth opening at different time points

According to Bielsa et al. [10], lesser trismus was observed when healing took place by simple approximation of margins than margin to margin suturing, which is following the present study as trismus was less in the sutureless group. Trismus may be attributed to any type of trauma to the muscle tissue, which may occur as a result of either excessive soft tissue retraction or due to increased duration of surgery contributing to increased inflammatory response. In secondary closure, the time of surgery was reduced as no sutures were to be placed. Moreover, a small incision facilitated the elevation of a relatively smaller flap in dimensions, further contributing towards a lesser degree of trauma to the muscles intra-operatively.

The periodontal sequelae were recorded by evaluating the distal aspect of the second molar for any pocket formation using William’s periodontal probe. The periodontal pocket depth of 4 mm was taken as normal in the study and was recorded in all the patients pre-operatively. Periodontal pocket was present pre-operatively in four cases of Group I (5 mm, 6 mm, 5 mm, and 5 mm) and one case of Group II (6 mm). The post-operative assessment was done at the time intervals of the immediate post-operative, second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth day. There was no change in periodontal pocket depth in these patients at any time interval post-operatively. In the remaining patients of both the groups, no periodontal pocket was recorded. Chi-square test, when applied, gave a statistically insignificant value of 2.000 (p = 0.157) (Graph 4).

Graph 4.

Depicting the periodontal pocket at different time points

According to Cunqueiro et al. [11] who compared two flap designs—marginal and para-marginal flaps that were used during impacted third molar surgery; the probing depth was similar with the use of both techniques at three months, which is in support of present study as periodontal pocket depth was constant in both the groups. In contrast to the present study, Rosa et al. [12] reported post-operative periodontal status at six months was worse than pre-operative status.

Haemorrhage was evaluated intra-operatively and post-operatively at 24 h and second day time interval. No haemorrhage was observed in any of the cases in either of the two groups. These results are contrasting the findings of the study conducted by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons which concluded an intra-operative frequency of unexpected haemorrhage of 0.7% and a post-operative frequency of unexpected or prolonged haemorrhage of 0.1%. Haug et al. [13] and Bui et al. [14] also found the frequency of clinically significant bleeding to be 0.6%. Chiapasco et al. [15] found excessive intraoperative bleeding in 0.7% of mandibular third molars and 0.6% incidence of post-operative excessive bleeding.

In the present study, no haemorrhage was observed in any of the cases at any time interval which may be attributed to a smaller flap design, i.e. the modified Szmyd incision which was used in all the cases. Moreover, cases in which the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle was found to be close to the root apices radiographically were excluded from the study.

Alveolar osteitis was clinically diagnosed by the presence or absence of severe pain as per the Verbal Pain Scale, loss of blood clot from the socket, and halitosis. No evidence of alveolar osteitis was observed in any of the cases in either of the two groups at an interval of the second, fifth, seventh, and fourteenth day. These results are not consistent with the study of Danda et al. [9] who observed that alveolar osteitis occurred in 4.3% in primary closure and 3.2% in secondary closure.

The absence of incidence of alveolar osteitis in the present study was probably because the modified Szmyd incision was used, which was smaller in size than the conventional Terence Wards incision, which reduced the chances of clot dislodgement. Although there were two cases in which the incision had to be extended due to the lack of adequate exposure. Both these patients reported with food lodgment post-operatively that was treated with regular saline irrigation. However, both these cases were excluded from the study.

The results obtained in the present study enable us to conclude that, pain; swelling, and trismus were found to be significantly less especially in the immediate post-operative period in the sutureless group as compared to the suture group in otherwise healthy patients. This was attributed to the fact that the sutureless group facilitated spontaneous irrigation and drainage of the inflammatory mediators. Modified Szmyd flap closure for the surgery resulted in a comparatively smaller defect thereby creating a possibility of a sutureless surgery, due to which there was no incidence of intra-operative and post-operative haemorrhage. Sutureless surgery was found to be time-saving and also a cost-effective method. Long-term follow-up of all the patients showed that there was no difference in periodontal sequelae and alveolar osteitis. Lastly, a study comprising of a larger sample size is required for the critical evaluation of all the parameters.

Summary and Conclusion

The surgical removal of impacted third molars is a common procedure in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgical practice and is associated with a diversity of techniques. The present study was undertaken to compare the flap closure with sutures versus sutureless surgery using a modified Szmyd flap for surgical removal of impacted lower third molars and to evaluate the morbidity and complications associated with each technique. This was attributed to the fact that the sutureless group facilitated spontaneous irrigation and drainage of the inflammatory mediators. Modified Szmyd flap closure for the surgery resulted in a comparatively smaller defect thereby creating a possibility of a sutureless surgery, due to which there was no incidence of intra-operative and post-operative haemorrhage. Sutureless surgery was found to be time-saving and also a cost-effective method. Long-term follow-up of all the patients showed that there was no difference in periodontal sequelae and alveolar osteitis. Lastly, a study comprising of a larger sample size is required for the critical evaluation of all the parameters.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dinesh Kumar, Email: dr_dinesh78@yahoo.com.

Parveen Sharma, Email: parveen66@yahoo.co.uk.

Shruti Chhabra, Email: naveenprisha@yahoo.co.in.

Rishi Bali, Email: rshbali@yahoo.co.in.

References

- 1.Saglam AA, Tuzum S. Clinical and radiological investigation of the incidence, complications and suitable removal times for fully impacted teeth in the Turkish population. Quintessence Int. 2003;34:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chukwuneke FN, Saheeb BDO. The effect of patient’s age and length of surgical intervention on post operative morbidity following lower third moalr surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;7(4):420–423. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson (2003) Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery. Mosby 205.

- 4.Waite PD, Cherala S. Surgical outcomes for suture less surgery in 366 impacted third molar patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:669–673. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubois DD, Pizer ME, Chinnis RJ. Comparison of primary and secondary closure techniques after removal of impacted third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982;40(10):631–634. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(82)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madan N, Keerthi R, Kumaraswamy SV, Anup GK. Comparative study of primary and secondary closure of surgical wound after removal of impacted mandibular third molar: a clinical study. Indian Dent Res Rev. 2010;4(12):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasqualini D, Cocero N, Castella A, Mela L, Bracco P. Primary and secondary closure of the surgical wound after removal of impacted mandibular third molars: a comparative study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saglam AA. Effects of tube drain with primary closure technique on post-operative trismus and swelling after removal of fully impacted mandibular third molars. Quintessence Int. 2003;34:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danda AK, Tatiparthi MK, Narayanan V, Siddareddi A. Influence of primary and secondary closure of surgical wound after impacted mandidular third molar removal on post-operative pain and swelling: a comparative and split mouth study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(2):309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bielsa JMS, Bazan SH, Diago MP. Flap repositioning versus conventional suturing in third molar surgery. Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13(2):38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunqueiro MMS, Gutwald R, Reichman J, Cepeda XLO, Schmelzeisen R, De Compostela S. Marginal Flap versus paramarginal flap in impacted third molar surgery: a prospective study. Oral Surg oral Med Oral Pathol Oral RadiolEndod. 2003;95:403–408. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosa AL, Carneiro MG, Lavrador MA, Novaes AB. Influence of flap design on periodontal healing of second molars after extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:404–407. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.122823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haug RH, Perrott DH, Gonzalez ML, Talwar RM. The American Association of oral and maxillofacial surgeon’s age-related third molar study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1106–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bui CH, Seldin EB, Dodson TB. Types, frequencies and risk factors for complications after third molar extraction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiapasco M, De Cicco L, Marrone G. Side effects and complications associated with third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;108:156–161. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90005-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]