Abstract

Three genetically distinct groups of Lactococcus lactis phages are encountered in dairy plants worldwide, namely, the 936, c2, and P335 species. The multiplex PCR method was adapted to detect, in a single reaction, the presence of these species in whey samples or in phage lysates. Three sets of primers, one for each species, were designed based on conserved regions of their genomes. The c2-specific primers were constructed using the major capsid protein gene (mcp) as the target. The mcp sequences for three phages (eb1, Q38, and Q44) were determined and compared with the two available in the databases, those for phages c2 and bIL67. An 86.4% identity was found over the five mcp genes. The gene of the only major structural protein (msp) was selected as a target for the detection of 936-related phages. The msp sequences for three phages (p2, Q7, and Q11) were also established and matched with the available data on phages sk1, bIL170, and F4-1. The comparison of the six msp genes revealed an 82.2% identity. A high genomic diversity was observed among structural proteins of the P335-like phages suggesting that the classification of lactococcal phages within this species should be revised. Nevertheless, we have identified a common genomic region in 10 P335-like phages isolated from six countries. This region corresponded to orfF17-orf18 of phage r1t and orf20-orf21 of Tuc2009 and was sequenced for three additional P335 phages (Q30, P270, and ul40). An identity of 93.4% within a 739-bp region of the five phages was found. The detection limit of the multiplex PCR method in whey was 104 to 107 PFU/ml and was 103 to 105 PFU/ml with an additional phage concentration step. The method can also be used to detect phage DNA in whey powders and may also detect prophage or defective phage in the bacterial genome.

Lactococcus lactis is the main lactic acid bacterium used in the manufacture of cultured dairy products such as cheese, sour cream, and buttermilk. The fermentation of milk by lactococci is a microbiological process that is vulnerable to bacteriophage attack. Furthermore, lactococcal lytic phages are the primary cause of fermentation failures in the dairy industry. These phages are classified within 12 genetically unrelated species or groups (18) but are all members of the Caudovirales order (1). Only three species of lactococcal lytic phages are encountered in dairy plants, namely, 936, c2, and P335 (27, 28). These three species of the Siphoviridae family share some important features, including a double-stranded DNA genome and a long noncontractile tail. The 936- and P335-like phages both have a small isometric head (morphotype B1), and the c2-like phages have a prolate head (morphotype B2). When the acidification step is retarded or arrested during milk fermentation, the first usual procedure is to examine the milk or whey samples for the presence of lytic phage using standard microbiological methods (plaque assay, activity test) (for review see reference 14). A positive result in the phage assay leads to a substitution of the existing bacterial starter culture for another phage-unrelated starter. In recent years, some starter culture suppliers have extended their analysis to isolate the phages and identify their species through electron microscopy analysis and/or DNA hybridization assays (25). This recent focus on phage identification is linked to the development of phage-resistant strains and to novel strain rotation strategies (25).

Decades of progress in the genetics of Lactococcus have resulted in the establishment of a solid basis for constructing new phage-resistant strains. Some L. lactis strains were found to naturally possess plasmids coding for antiphage systems. More than 40 different lactococcal antiphage plasmids have been reported in the literature (12). The resistance is often broad and effective against most phages of the same species. A limited number of systems are even potent against more than one phage species (2). These discoveries have had a significant impact, as many control strategies have come to be based on phage species rather than on phage isolates, such as the introduction of a species-specific resistance mechanism into a phage-sensitive L. lactis strain. Another means of controlling phages is through the use of strain rotation based on phage species sensitivity (27). Thus, there is now an increasing interest in rapidly characterizing lactic phages in dairy samples.

Microbiological methods have the advantage of providing information about the sensitivity of a culture but do not discern phage species. On the other hand, molecular techniques such as DNA probes (29) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (21, 26) can determine the nature of the phage species but do not detect active lytic cycles. The current molecular systems also have a low sensitivity (107 PFU/ml) and need multiple reactions to identify the distinct species (one reaction per species). PCR is fundamentally designed to amplify DNA (34). PCR is also extensively used as a detection and identification tool for viruses and bacteria in different environments (3, 4, 7, 11, 32, 33, 38, 40, 42). The PCR method has been adapted for the detection of Streptococcus thermophilus phages in cheese whey, with a detection limit of 103 PFU/ml (7). But unlike L. lactis phages, all known S. thermophilus phages have DNA homology.

It is now well known that food components may interfere with PCR. Many publications have addressed this problem by describing the use of specific conditions to avoid an inhibition of PCR. The solutions include dilution of the sample, preenrichment or isolation of the target microorganism, cell wash with phosphate-buffered saline (11), purification of total DNA by phenol-chloroform extraction or an ion exchange affinity column (7, 38, 42), and immunomagnetic separation of the target (32). Powell et al. (33) also reported that proteinases (such as milk plasmin) could also inhibit PCR. The addition of bovine serum albumin or proteinase inhibitors can prevent the inhibitory effect. The presence of calcium (>3 mM) has also been shown to obstruct the PCR assay by competing with magnesium, an essential cofactor of the Taq DNA polymerase (4). The use of a chelating agent (EGTA) or an increase of the Mg2+ concentration can restore the Taq activity. Obviously, these additional steps are time-consuming and have made the use of PCR less attractive in routine applications.

Here, we report the first multiplex PCR to detect, in one reaction, the presence of the three major lactococcal phage species directly from whey samples.

(Part of this work was presented at the 93rd Annual Meeting of the American Dairy Science Association, Denver, Colo. [20].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, phages, and media.

The bacterial strains and phages used in this study are listed in Table 1. L. lactis strains were grown at 30°C in M17 broth (39) containing 0.5% glucose (GM17) or lactose (LM17) (Quélab, Montréal, Québec, Canada). Phages were propagated on their hosts as described by Jarvis (15). Phages were purified on a discontinuous-step cesium chloride gradient followed by a one-step continuous gradient (9).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and bacteriophages used in this study

| L. lactis strain or phage | Relevant characteristics | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| LM0230 | Plasmid free; host for phages c2, c21, eb1, ml3, p2, and sk1 | 24 |

| F4/7 | Host for phages P270 and P008 | H. W. Ackermanna |

| F4/2 | Host for phage P335 | H. W. Ackermann |

| LLC509.9 | Indicator strain; host for phage Tuc2009 | D. van Sinderenb |

| IMN-C18 | Host for phage φLC3 | D. Lillehaugc |

| R1K10 | Indicator strain; host for phage r1t | A. Nautad |

| SMQ-86 | UL8 (pSA3); Emr; host for phages, Q30, φ31, Q33, ul36, ul40, φ48, and φ50 | 9 |

| SMQ-189 | Industrial strain; host for phage Q7 | 9, 27 |

| SMQ-195 | Industrial strain; host for phage Q11 | 9, 27 |

| SMQ-196 | Industrial strain; host for phages Q38 and Q44 | 9, 27 |

| SMQ-203 | Industrial strain; host for phage Q42 | 9, 27 |

| SMQ-389 | Industrial strain; host for phages HD1 and HD3 | 5 |

| SMQ-392 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD2 | 5 |

| SMQ-401 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL1 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-402 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL2 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-403 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL3 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-404 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL4 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-405 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL5 | 5 |

| SMQ-406 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL6 and SL8 | 5 |

| SMQ-407 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL7 | 5 |

| SMQ-408 | Industrial strain; host for phages SL9, SL10, and SL11 | 5 |

| SMQ-409 | Industrial strain; host for phage SL12 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-413 | Industrial strain; host for phages HD5 and HD6 | 5 |

| SMQ-421 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD13 | 5 |

| SMQ-422 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD14 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-423 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD8 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-424 | Industrial strain; host for phages HD10 and HD21 | 5 |

| SMQ-425 | Industrial strain; host for phages HD9 and HD22 | 5 |

| SMQ-426 | Industrial strain; host for phages HD11 and HD12 | 5 |

| SMQ-427 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD15 | 5 |

| SMQ-428 | Industrial strain; host for phages HD16, HD17, HD18, and HD19 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-489 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD20 | 5; this study |

| SMQ-491 | Industrial strain; host for phage HD24 | 5 |

| Bacteriophages | ||

| sk1 | Small isometric head, 936 species, USAf | 8 |

| p2 | Small isometric head, 936 species, USA | 24, 31 |

| Q7 | Small isometric head, 936 species, USA | 27 |

| P008 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Germany | H. W. Ackermann |

| Q11 | Small isometric head, 936 species, USA | 27 |

| Q40 | Small isometric head, 936 species, USA | 27 |

| Q42 | Small isometric head, 936 species, USA | 27 |

| SL1 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| SL2 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| SL3 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| SL4 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| SL5 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| SL6 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| SL7 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| SL8 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| SL9 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| SL10 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| SL11 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| SL12 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD3 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD5 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD6 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD8 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD9 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD10 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD11 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD12 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD13 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD14 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD15 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD16 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD17 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD18 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD19 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD20 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5; this study |

| HD21 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD22 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD24 | Small isometric head, 936 species, Canada | 5 |

| eb1 | Prolate head, c2 species, USA | 24 |

| c2 | Prolate head, c2 species, USA | 24 |

| c21 | Prolate head, c2 species, USA | 24 |

| ml3 | Prolate head, c2 species, USA | 24 |

| Q38 | Prolate head, c2 species, USA | 27 |

| Q44 | Prolate head, c2 species, USA | 27 |

| HD1 | Prolate head, c2 species, Canada | 5 |

| HD2 | Prolate head, c2 species, Canada | 5 |

| Q30 | Small isometric head, P335 species, USA | 27 |

| φ31 | Small isometric head, P335 species, USA | T. R. Klaenhammere |

| Q33 | Small isometric head, P335 species, USA | 27; this study |

| ul36 | Small isometric head, P335 species, Canada | 28 |

| ul40 | Small isometric head, P335 species, Canada | This study |

| φ48 | Small isometric head, P335 species, USA | T. R. Klaenhammer |

| φ50 | Small isometric head, P335 species, USA | T. R. Klaenhammer |

| P270 | Small isometric head, P335 species, France | H. W. Ackermann |

| P335 | Small isometric head, P335 species, Germany | T. R. Klaenhammer |

| Tuc2009 | Small isometric head, P335 species, The Netherlands | D. van Sinderen |

| φLC3 | Small isometric head, P335 species, Norway | D. Lillehaug |

Université Laval.

College Cork, Cork, Ireland.

The Agricultural University of Norway.

University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

North Carolina State University.

USA, United States.

Phage DNA analysis.

The Maxi Lambda DNA purification kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) was used for phage DNA purification as recommended by the manufacturer, except that the L2 buffer was modified to provide a final concentration of 10% polyethylene glycol (molecular weight, 8,000) and 0.5 M sodium chloride for an effective precipitation of lactococcal phages. The concentration of phage DNA was estimated with a Beckman DU series 500 spectrophotometer as described by Sambrook et al. (35).

Protein profiles and N-terminal sequencing.

The method of Braun et al. (6) was used to determine the structural protein profiles of lactococcal phages. Proteins were separated through a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–15% polyacrylamide minigel at 100 V with the Mini-Protean II apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) as described previously (9). Prestained molecular mass markers were used as molecular masses (New England Biolabs, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). After separation, the proteins were transferred with a Trans-Blot apparatus (Bio-Rad) to a polyvinylidene difluoride Immobilon-PSQ membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) using CAPS buffer (10 mM 3-cyclohexylamino-1-propanesulfonic acid, pH 11). After the staining of the membrane (0.1% Coomassie blue, 40% methanol, 1% acetic acid), N-terminal sequencing of the 40-kDa bands of five 936 phages (p2, Q7, Q11, Q42, and Q46) was performed using an Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.) model 473A pulsed-liquid protein sequencer.

DNA sequencing, primer synthesis, and bioinformatic analyses.

DNA sequencing was performed using synthesized primers. The total phage genome was used as a template. The sequence of the gene coding for the major capsid protein was determined for three phages (eb1, Q38, and Q44) belonging to the c2 species. These sequences were compared to that of orfl5 of phage c2 (accession no. L48605 [22]) and orf26 of bIL67 (accession no. L33769 [36]). The sequence of gene coding for the major structural protein was established for three phages (p2, Q7, and Q11) of the 936 species. The sequences were compared to that of orf11 of sk1 (accession no. AF011378 [8]), to that of orfl13 of bIL170 (accession no. AF009630), and to that of the mcp gene of phage F4-1 (accession no. M37979 [19]). Nucleic acid sequences were obtained using an Applied Biosystems 373A automated DNA sequencer. Primers were synthesized with an Applied Biosystems 394 DNA/RNA synthesizer. Sequence alignments and protein analyses were performed with the programs included in the Genetics Computer Group sequence analysis software package, version 10.0 (13).

Genome analysis of P335 phages.

To determine the PCR target for the P335 species, the genomes of nine P335 phages were digested with EcoRI, electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane (Roche Diagnostic, Laval, Québec, Canada) (30). The Dig Easy Hyb (Roche Diagnostic) was used as the prehybridization and hybridization solutions. Comparison of the two completely sequenced P335 genomes, namely, those of r1t and Tuc2009, allowed the identification of conserved regions as well as the subsequent construction of a series of probes (PCR products) from these homologous DNA stretches. The probes were labeled with digoxigenin, using DIG High Prime (Roche Diagnostic). Chemiluminescent-immunological detection of DNA was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. DNA fragments homologous to orf17-orf18 of phage r1t (accession no. U38906 [41]) and orf20-orf21 of Tuc2009 (D. van Sinderen, personal communication) in phages Q30, ul40, and P270 were sequenced.

Multiplex PCR.

The three pairs of primers (one per phage species) that were designed from the conserved regions are listed in Table 2. PCRs were performed in 50 μl containing 125 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d'Urfé, Québec, Canada), 5 mM concentrations of the six primers, 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostic), Taq buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 mM magnesium chloride, 50 mM potassium chloride, pH 8.3), and 1 μl of the template. The mixture was overlaid with PCR grade mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The template was made up of phage DNA, phage lysate, bacterial cells, whey, and reconstituted (6%) or filtered whey. The latter was prepared as follows: 1 ml of whey was centrifuged at 23,600 × g for 10 min and then filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (FisherBrand; Fisher Scientific, Nepean, Ontario, Canada) to eliminate the bacterial cells. Phage DNA (10 pg) was used as a positive control. A negative control (without the template) was included for all PCR assays to eliminate the risk of contamination. PCR conditions were optimized on a Robocycler gradient 40 apparatus (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and were subsequently set as follows: 5 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles (45 s at 94°C, 1 min at 58°C, 1 min at 74°C) and a final step of 5 min at 74°C. The PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA), stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV light (35).

TABLE 2.

List of primers used for the multiplex PCR

| Primer | Sequence | Position in the sequence | PCR product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 936A | TCAATGGAAGACCAAGCGGA | 166–185 | 179 |

| 936B | GTAGGAGACCAACCCAAGCC | 344–325 | |

| c2A | CAGGTGTAAAAGTTCGAGAACT | 461–482 | 474 |

| c2B | CAGATAATGCACCTGAATCA | 934–915 | |

| P335A | GAAGCTAGGCGAATCAGTAA | 53–72 | 682 |

| P335B | GATTGCCATTTGCGCTCTGA | 734–715 |

Detection limit and competition assay.

Cheese whey free of phages (no PCR product) was artificially contaminated with a known titer (1, 2, or 3) of purified phages Q7 (936-like), Q30 (P335-like), and Q38 (c2-like). Serial dilutions of the contaminated whey were made, and the PCR was performed as described above. The lowest concentration visible on an agarose gel was set as the detection limit.

Phage concentration.

The sensitivity of the method was improved by concentrating the phages present in 1 ml of whey. First, the sample was centrifuged at 23,600 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and placed in an Eppendorf tube. After the addition of 500 μl of the concentration buffer (30% polyethylene glycol, 1.5 M sodium chloride), the samples were placed at 4°C under slow agitation for 2 h. Phages were precipitated by centrifugation at 23,600 × g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 10 μl of distilled water, and 1 μl was directly used as the PCR template.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The accession numbers for the DNA sequences determined in this study are AF152410, AF152411, and AF152412 for the mcp genes of phages eb1, Q38, and Q44, respectively; AF152407, AF152409, and AF152408 for the msp genes of phages p2, Q7, and Q42, respectively; and AF152414, AF152415, and AF152413 for the conserved regions in phages Q30, ul40, and P270, respectively.

RESULTS

The mcp genes of c2-like phages.

Using monoclonal antibodies, we previously showed that the major capsid protein was conserved among the c2-like phages (9). The mcp sequence was determined for three c2-like phages, namely, eb1, Q38, and Q44. These sequences were compared to those of the mcp genes of phages c2 (22) and bIL67 (36), which were already available. The homology between the five genes was 86.4% (data not shown). At the protein level, the identity increased to 93.0% and the similarity increased to 96.0%. Conserved DNA regions were found within these sequences.

The msp genes of 936-like phages.

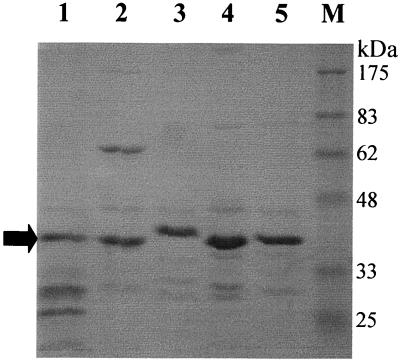

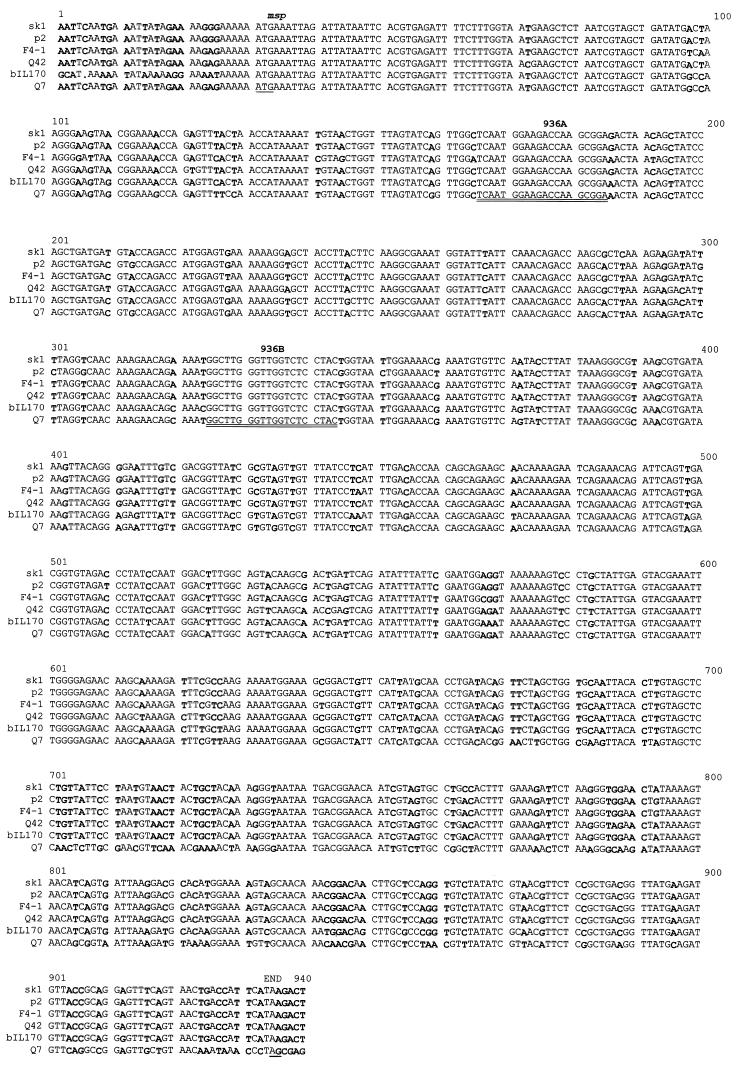

Previous studies have shown that the structural protein profiles are highly conserved among the 936-like phages (6, 28). The protein profiles of five members (p2, Q7, Q11, Q42, and Q46) of the 936 species were confirmed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and they contained only one major structural protein of approximately 40 kDa (Fig. 1). The N-terminal sequencing of the 40-kDa protein showed that the first 10 amino acids were identical for the five phages (MKLDYNSREI). The gene of this protein was previously characterized for the phages F4-1 (19), sk1 (8), and bIL170. This protein was identified as the major capsid protein by Kim and Batt (19), but Chandry et al. (8) suggested that the gene possibly coded for the major tail protein. The nucleotide sequence of the gene was determined for the phages p2, Q7, and Q11. The alignment of the six msp sequences showed an 82.2% identity (Fig. 2). At the protein level, the identity was 84.7% and the similarity was 91.7%. Several stretches of DNA were also conserved in these six phages.

FIG. 1.

Protein profiles of 936-related phages as determined by SDS–15% PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Lane 1, phage p2; lane 2, Q7; lane 3, Q11; lane 4, Q42; lane 5, Q46; lane M, prestained molecular mass markers (New England Biolabs). Arrow, major structural protein used for N-terminal sequencing and encoded by the msp gene.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence alignment of the gene coding for the major structural proteins of six members of the 936 species. The sequence differences are indicated by boldface. The start and nonsense codons are underlined. The regions selected for the PCR primers are indicated by a double underline (936A and 936B).

A conserved region in P335-like phages.

An SDS-PAGE was performed with four phages of the P335 species (Fig. 3). Significant variations within the structural proteins of these phages were observed. Using monoclonal antibodies, we previously showed that the major capsid protein was not well conserved among the P335-like phages (26). DNA sequence alignment of the entire genomes of phages r1t and Tuc2009 confirmed the heterogeneity between these two P335 phages (D. van Sinderen, personal communication). The very few conserved regions between these two phages were used as probes in the DNA hybridization experiments to screen other P335 phages. A region corresponding to orf17-orf18 of phage r1t and orf20-orf21 of Tuc2009 was present in all P335-like phages tested except for ul36 (data not shown). The function of the putative proteins is unknown. This region was sequenced for three additional P335 phages (Q30, P270, and ul40). The comparison of the three sequences with the sequences available for r1t (41) and Tuc2009 (D. van Sinderen, personal communication) shows a nucleotide identity of 93.4% (data not shown). At the protein level, the identity decreased slightly to 89.2% and the homology dropped to 91.6% because of a frameshift.

FIG. 3.

SDS–15% PAGE of CsCl-purified P335-related phages. Lane 1, Q30; lane 2, φ31; lane 3, P270; lane 4, ul36; lane M, prestained molecular mass markers (New England Biolabs).

Detection of lactococcal phages with the multiplex PCR.

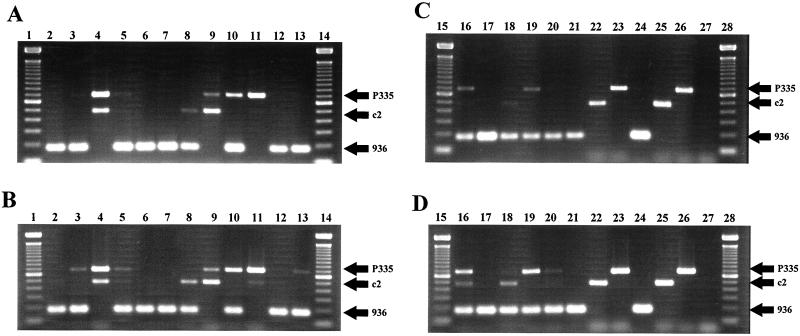

Since conserved DNA regions were found within each phage species, several pairs of primers were tested to avoid nonspecific amplification or interference in the multiplex PCR assay (data not shown). The primers were also designed to obtain PCR products of different sizes (Fig. 4, lanes 24 to 27). Primers 936A and 936B gave a PCR product of 179 bp. Primers c2A and c2B yielded a 474-bp product, and primers P335A and P335B produced a 682-bp fragment. The PCR method was successfully tested against 54 distinct lactococcal phages (Table 1). The PCR was suitable with whey samples, M17, or Tris-HCl buffer as well as phage particles or phage DNA (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Multiplex PCR competition assay for different combinations of phage species in the same sample. Phage Q7 represents the 936 species, Q30 represents the P335 species, and Q38 represents the c2 species. Reactions were carried out with 1.25 (A and C) and 2.50 (B and D) U of Taq DNA polymerase. Lanes (boldface, phage concentration of 108 PFU/ml; lightface, phage concentration of 107 PFU/ml): 1, 14, 15, and 28, 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco/BRL, Burlington, Ontario, Canada); 2, 936 plus c2; 3, 936 plus P335; 4, c2 plus P335; 5, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 6, 936 plus c2; 7, 936 plus P335; 8, 936 plus P335; 9, c2 plus P335; 10, 936 plus P335; 11, c2 plus P335; 12, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 13, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 16, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 17, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 18, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 19, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 20, 936 plus c2 plus P335; 21, 936; 22, c2; 23, P335; 24, 10 pg of 936 DNA; 25, 10 pg of c2 DNA; 26, 10 pg of P335 DNA; 27, negative control.

Detection limit of the multiplex PCR.

Serial dilution of purified phages in whey was used to determine the sensitivity of the PCR assay for each of the species. The detection limit was different for each phage species. For the 936 species, the detection limit was 104 PFU/ml of whey and was 103 PFU/ml with the concentration step. For the c2 species, the detection limits were 107 and 105 PFU/ml of whey without and with the concentration step, respectively. Finally for the P335 species, the levels were 105 and 103 PFU/ml before and after concentration, respectively.

Kinetics of amplification during the multiplex PCR competition assay.

Although multiple phage species are rarely found within one whey sample (5), the PCR assay was still used to test whey samples artificially contaminated with different phage species (Fig. 4). The c2 and P335 PCR products were codominant, as they can be amplified concurrently. However, the 936 PCR product was dominant over the two others when the phages were present at the same concentration in the sample. The c2 and P335 signals could be recovered when the concentration of 936 phage was 10-fold less than the concentrations of the other species. The PCR product can also be retrieved by a twofold increase in the Taq polymerase concentration.

Other applications.

The PCR method was also used to detect the presence of phage DNA (P335 species) within the bacterial chromosome. Overnight cultures yielded a PCR product specific for the P335 phages in 18 of 26 industrial L. lactis strains tested (data not shown). Testing for the presence of phage DNA in eight lots of rehydrated (6%) whey powders was also performed. All samples from these lots were found to contain DNA belonging to the 936-like phages.

DISCUSSION

The PCR assay reported here has the advantage of simultaneously detecting, in one reaction, the presence of lactococcal phages as well as their species directly from whey samples. The method cannot, however, establish whether the phages are able to attack a starter culture or if the phages are viable. Thus, this method may be used to confirm the presence of phages in a positive sample (by microbiological assay) and, most significantly, to rapidly indicate to which species they belong. The latter is of critical importance for a rotation scheme and for the appropriate selection of an antiphage mechanism (25).

Phages are ubiquitous in dairy plants, as they are normally found in both raw and pasteurized milk (10, 16, 23). McIntyre et al. showed that the phage titer in raw milk samples ranged between 101 and 104 PFU/ml (23). They also demonstrated that virulent phages (attacking the starter culture) were at concentrations of 105 to 108 PFU/ml in whey samples. The detection limits of the PCR method described in this study were between 104 and 107 PFU/ml. Although the sensitivity can be improved by polyethylene glycol precipitation, caution should be exercised, as the normal phage flora could be detected rather than the problematic ones (false positive). In fact, any additional step designed to increase the intrinsically low sensitivity of the PCR assay should be avoided in the detection of lactic phages. Furthermore, filtration of the milk sample is equally critical, as prophage DNA (contained in starter cells) can be detected with a PCR assay. So far, only phages of the P335 species are known to include lytic and temperate phages (18). The detection of phage DNA within whey powders was not that surprising, as many phages survive pasteurization and spray-drying conditions (10).

In this study, no inhibition of the PCR assay was observed with whey samples. As only 1 μl of centrifuged or filtrated whey was used per reaction (in a final volume of 50 μl), potential PCR inhibitors such as calcium and plasmin may have been below their interfering concentrations.

Cheddar whey generally contains between 10 and 12 mM calcium (37). In the PCR conditions used here, this corresponded to approximately 0.2 mM (1:50), which is well below the 3 mM needed for inhibition (4). The absence of proteinase activity can also be explained by the amount of whey used in the reaction mixture. Furthermore, Powell et al. (33) showed that a PCR mixture containing more than 1% milk alleviates the inhibition of the Taq by proteinases. Here, 2% whey (1:50) was used in the PCRs. The presence of whey may have a similar role in protecting the polymerase from degradation.

The 936 and c2 species have been disturbing milk fermentations for many years, but only recently have the P335-like phages emerged with increasing frequencies in cheese plants (30). Jarvis had previously demonstrated weak DNA homology between some P335-like phages (17). The variation in the protein profiles and in the DNA homology, two criteria normally used to classify phages (1), suggests that further work is needed to clarify the current classification of the P335 phages. A study to address this issue is under way in our laboratory. Nonetheless, orf17 and orf18 of phage r1t were present in 10 of the 11 P335-like phages tested. Although the functions of these putative genes are unknown, their high degree of homology suggests a meaningful role in their respective lytic cycles. Only phage ul36 could not be detected by PCR. The absence of these two genes in phage ul36 is intriguing. We are currently sequencing its genome to shed light on its evolution.

As additional phages are tested, it is possible that the primers may not detect their presence due to sequence variability. Reducing the hybridization temperature may still enable the detection of some phages, but modifying the primer(s) could constitute another alternative. This is a first-generation PCR-based system for the detection of lactococcal phages, and other versions are likely to be developed or refined in the near future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H.-W. Ackermann, T. R. Klaenhammer, D. Lillehaug, and A. Nauta for providing P335 phages. We are also very grateful to D. van Sinderen for providing phage Tuc2009 and its genomic sequence prior to publication. We also thank S. R. Chibani Azaïez for fruitful discussions and S. Bourassa for peptide sequences.

S.L. is a recipient of a Fonds FCAR graduate scholarship. This work was supported by strategic grants from FCAR-Novalait-CQVB and by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann H-W. Tailed bacteriophages: the order Caudovirales. Adv Virus Res. 1999;51:135–201. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60785-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison G E, Klaenhammer T R. Phage resistance mechanisms in lactic acid bacteria. Int Dairy J. 1998;8:207–226. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allmann M, Höfelein C, Köppel E, Lüthy J, Meyer R, Niederhausser C, Wegmüller B, Candrian U. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of pathogenic microorganisms in bacteriological monitoring of dairy products. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:85–97. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickley J, Short J K, McDowell D G, Parkes H C. Polymerase chain reaction of Listeria monocytogenes in diluted milk and reversal of PCR inhibition caused by calcium ions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bissonnette, F., S. Labrie, H. Deveau, M. Lamoureux, and S. Moineau. Characterization of mesophilic mixed starter cultures used for the manufacture of aged Cheddar cheese. J. Dairy Sci., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Braun V, Jr, Hertwig S, Neve H, Geis A, Teuber M. Taxonomic differentiation of bacteriophages of Lactococcus lactis by electron microscopy, DNA-DNA hybridization, and protein profiles. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:2551–2560. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brüssow H, Fremont M, Bruttin A, Sidoti J, Constable A, Fryder V. Detection and classification of Streptococcus thermophilus bacteriophages isolated from industrial milk fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4537–4543. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4537-4543.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandry P S, Moore S C, Boyce J D, Davidson B E, Hillier A J. Analysis of the DNA sequence, gene expression, origin of replication and modular structure of the Lactococcus lactis lytic bacteriophage sk1. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:49–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5491926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chibani Azaïez S R, Fliss I, Simard R E, Moineau S. Monoclonal antibodies raised against native major capsid proteins of lactococcal c2-like bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4255–4259. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4255-4259.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopin M-C. Resistance of 17 mesophilic lactic Streptococcus bacteriophages to pasteurization and spray-drying. J Dairy Res. 1980;47:131–139. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900020963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooray K J, Nishibori T, Xiong H, Matsuyama T, Fujita M, Mitsuyama M. Detection of multiple virulence-associated genes of Listeria monocytogenes by PCR in artificially contaminated milk samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3023–3026. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.3023-3026.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daly C, Fitzgerald G F, Davis R. Biotechnology of lactic acid bacteria with special reference to bacteriophage resistance. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:99–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00395928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everson T C. Control of phage in the dairy plant. Bull Int Dairy Fed. 1991;263:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis A W. Serological studies of a host range mutant of a lactic streptococcal bacteriophage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;36:785–789. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.6.785-789.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarvis A W. Sources of lactic streptococcal phages in cheese plants. N Z J Dairy Sci. 1987;22:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis A W. Relationships by DNA homology between lactococcal phages 7-9, P335 and New Zealand industrial lactococcal phages. Int Dairy J. 1995;36:785–789. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis A W, Fitzgerald G F, Mata M, Mercenier A, Neve H, Powell I A, Ronda C, Saxelin M, Teuber M. Species and type phages of lactococcal bacteriophages. Intervirology. 1991;32:2–9. doi: 10.1159/000150179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J H, Batt C A. Nucleotide sequence and deletion analysis of a gene coding for a structural protein of Lactococcus lactis bacteriophage F4-1. Food Microbiol. 1991;8:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labrie S, Moineau S. Multiplex PCR method for the detection and identification of Lactococcus lactis phages of the 936 and c2 species. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81(Suppl. 1):33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lembke J, Teuber M. Detection of bacteriophages in whey by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Milchwissenschaft. 1979;34:457–458. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubbers M W, Waterfield N R, Beresford T P J, Le Page R W F, Jarvis A W. Sequencing and analysis of the prolate-headed lactococcal bacteriophage c2 genome and identification of the structural genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4348–4356. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4348-4356.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McIntyre K, Heap H A, Davey G P, Limsowtin G K Y. The distribution of lactococcal bacteriophage in the environment of a cheese manufacturing plant. Int Dairy J. 1991;1:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKay L L, Baldwin K A, Zottola E A. Loss of lactose metabolism in lactic streptococci. Appl Microbiol. 1972;23:1090–1096. doi: 10.1128/am.23.6.1090-1096.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moineau S. Applications of phage resistance in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:377–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moineau S, Bernier D, Jobin M, Hébert J, Klaenhammer T R, Pandian S. Production of monoclonal antibodies against the major capsid protein of the Lactococcus bacteriophage ul36 and development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for direct phage detection in whey and milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2034–2040. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2034-2040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moineau S, Borkaev M, Holler B J, Walker S A, Kondo J K, Vedamuthu E R, Vandenbergh P A. Isolation and characterization of lactococcal bacteriophages from cultured buttermilk plants in the United States. J Dairy Sci. 1996;79:2104–2111. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moineau S, Fortier J, Ackermann H-W, Pandian S. Characterization of lactococcal bacteriophages from Quebec cheese plants. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:875–882. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moineau S, Fortier J, Pandian S. Direct detection of lactococcal bacteriophages in cheese whey using DNA probes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;92:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moineau S, Pandian S, Klaenhammer T R. Evolution of a lytic bacteriophage via DNA acquisition from the Lactococcus lactis chromosome. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1832–1841. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1832-1841.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moineau S, Walker S A, Vedamuthu E R, Vandenbergh P A. Cloning and sequencing of LlaDCHI restriction and modification genes from Lactococcus lactis and relatedness of this system to the Streptococcus pneumoniae DpnII system. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2193–2202. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2193-2202.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muramatsu Y, Yanase T, Okabayashi T, Ueno H, Morita C. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in cow's milk by PCR–enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay combined with a novel sample preparation method. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2142–2146. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2142-2146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell H A, Gooding C M, Garrett S D, Lund B M, McKee R A. Proteinase inhibition of the detection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk using the polymerase chain reaction. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schouler C, Ehrlich S D, Chopin M-C. Sequence and organization of the lactococcal prolate-headed bIL67 phage genome. Microbiology. 1994;140:3061–3069. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sienkiewicz T, Riedel C L. Whey and whey utilization. Gelsenkirchen-Buer, Germany: Verlag Th. Mann; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starbuck M A, Hill P J, Stewart G S. Ultra sensitive detection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:248–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1992.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Urbach E, Schindler C, Giovannoni S J. A PCR fingerprinting technique to distinguish isolates of Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;162:111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Sinderen D, Karsens H, Kok J, Terpstra P, Ruiters M H J, Venema G, Nauta A. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of the lactococcal bacteriophage r1t. Mol Microbiol. 1995;19:1343–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wernars K, Heuvelman C J, Chakraborty T, Notermans S H W. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for direct detection of Listeria monocytogenes in soft cheese. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb04437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]