Abstract

The group that includes the lactic acid bacteria is one of the most diverse groups of bacteria known, and these organisms have been characterized extensively by using different techniques. In this study, 180 lactic acid bacterial strains isolated from sorghum powder (44 strains) and from corresponding fermented (93 strains) and cooked fermented (43 strains) porridge samples that were prepared in 15 households were characterized by using biochemical and physiological methods, as well as by analyzing the electrophoretic profiles of total soluble proteins. A total of 58 of the 180 strains were Lactobacillus plantarum strains, 47 were Leuconostoc mesenteroides strains, 25 were Lactobacillus sake-Lactobacillus curvatus strains, 17 were Pediococcus pentosaceus strains, 13 were Pediococcus acidilactici strains, and 7 were Lactococcus lactis strains. L. plantarum and L. mesenteroides strains were the dominant strains during the fermentation process and were recovered from 87 and 73% of the households, respectively. The potential origins of these groups of lactic acid bacteria were assessed by amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprint analysis.

The group that includes the lactic acid bacteria is a heterogeneous group of bacteria that are generally regarded as safe for use in food and food products (15). The use of these organisms in food products dates back to ancient times, and they are used mainly because of their contributions to flavor, aroma, and increased shelf life of fermented products (28). Various members of this group are used commercially as starter cultures in the manufacture of food products, including dairy products (39), fermented vegetables (25), fermented doughs (45), alcoholic beverages (33, 34), probiotics in animal feeds (8), and meat products (44). Lactic acid bacteria have also been used for lactic acid fermentation of sorghum- or maize-based cereals used as infant-weaning foods (26, 27, 31, 38).

Various techniques have been used to characterize lactic acid bacteria; these techniques include whole-cell protein analysis, cell wall composition analysis, and morphological, physiological, and biochemical analyses (41). While combined use of these methods is invaluable for distinguishing lactic acid bacteria at the species level, the methods are not sufficiently discriminatory to differentiate organisms at the subspecies and strain levels (11, 14). Determining the electrophoretic patterns of total soluble proteins and computer-assisted analysis of the resulting protein profiles are well-established procedures in bacterial taxonomy (13, 23, 35). This technique has been used for taxonomic studies of lactic acid bacteria obtained from meat, dairy products, and other environments, but it is hampered by the fact that it can yield discriminatory information only at the species level, which requires some degree of preidentification. This problem has been overcome by creating a database of digitized and normalized protein patterns for most known species of lactic acid bacteria (35).

DNA-based techniques, such as DNA base ratio analysis, DNA-DNA hybridization analysis, rRNA homology analysis, plasmid profiling, ribotyping, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, have also been used to characterize lactic acid bacteria (42). However, some of these techniques have been hampered by a lack of reproducibility of results between experiments (randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis) and requirements for large amounts of time and labor (1). Recently, workers developed amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis, which detects genetic variation in microorganisms. The variation is assessed at a large number of independent loci and can be found in any part of the genome without prior knowledge of the sequence (47). The results are highly reproducible, as the technique is based on selective amplification with primers that recognize double-stranded DNA adapters that are ligated to the ends of DNA fragments in order to generate template DNA for amplification under stringent conditions. This technique has been used in taxonomic studies of Acinetobacter strains (18) and Aeromonas strains (17), in epidemiological studies of Bacillus anthracis strains (21), Salmonella strains (1), and Xanthomonas translucens strains (7), and in determining Vibrio vulnificus biotypes (2). It has also been used to determine molecular evolutionary origins and geographic correlations of Pseudomonas syringae strains (9).

The objectives of this study were to characterize lactic acid bacteria that occur naturally in sorghum powder and corresponding fermented and cooked fermented porridge samples by using both physiological and biochemical methods and analyzing total-soluble-protein patterns. In this study we also investigated the identities and origins of lactic acid bacteria that are dominant during the fermentation process by using AFLP fingerprinting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture selection and maintenance.

The 180 lactic acid bacterial strains used in this study were obtained during a previous microbiological survey of 45 sorghum samples collected from an informal settlement in the Gauteng Province of South Africa (24). These lactic acid bacteria were isolated from plate count preparations of sorghum powder samples (44 strains) and corresponding fermented (93 strains) and cooked fermented (43 strains) porridge samples. Presumptive lactic acid bacterial colonies were randomly selected from MRS agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, England) plates supplemented with 0.1% l-cysteine monohydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) (12) and 40 μg of cycloheximide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) per ml (30). The isolates were purified by growing them on MRS agar at 25°C for 48 h. Working cultures were maintained on MRS agar plates and were subcultured every 3 weeks. Stock cultures were maintained in MRS broth (Oxoid) supplemented with 30% glycerol and were stored at −70°C. Thirteen reference strains were included (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Reference strains used to characterize lactic acid bacterial isolates

| Species or subspecies | Straina |

|---|---|

| Lactobacillus alimentarius | DSM 20249T |

| Lactobacillus brevis | DSM 20054T |

| Lactobacillus casei | DSM 20011T |

| Lactobacillus confusus (Weissella confusa) | DSM 20196T |

| Lactobacillus coryniformis | DSM 20001T |

| Lactobacillus curvatus | DSM 20019T |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | DSM 20174T |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris | DSM 20069 |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis | DSM 20481 |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides | DSM 20343T |

| Leuconostoc paramesenteroides | DSM 20288T |

| Pediococcus acidilactici | DSM 20284 |

| Pediococcus pentosaceus | DSM 20336 |

DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen (Braunschweig, Germany).

Analysis of total-soluble-protein profiles.

Protein extracts were obtained from 180 strains by a previously described method (13) and were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels by using a model SE 600 electrophoresis apparatus (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, Calif.); the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Midrange molecular weight markers (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) were used as standards. Images were captured (UVP Image store 5000; Ultra Violet Products Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom), and electrophoretic patterns were analyzed by using the software package GelManager, version 1.5 (Biosystematica, Devon, United Kingdom). Levels of similarity between patterns were calculated by using the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (5). Strains were clustered by using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) (5), and the clusters were delineated at an arbitrary r level of 0.60.

Physiological and biochemical tests.

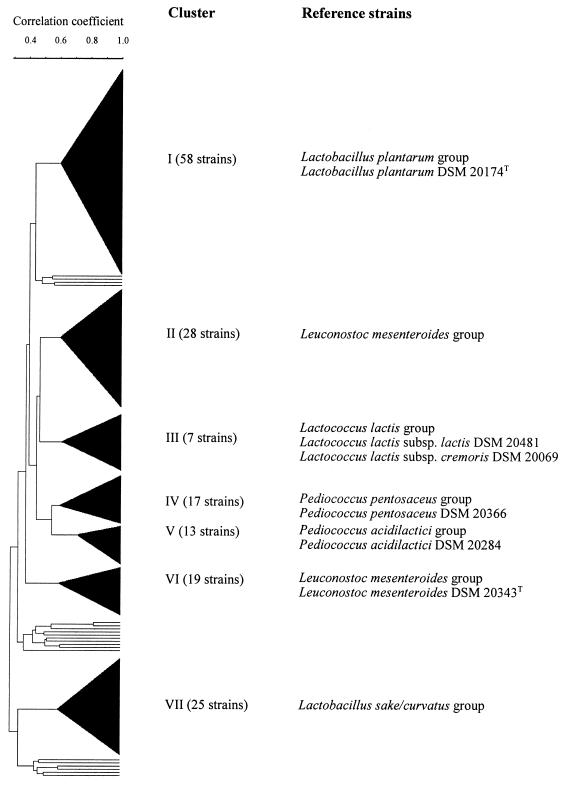

Of the 180 isolates analyzed in this study, 72 were randomly selected from clusters obtained from the electrophoretic profiles of total soluble proteins (Fig. 1), and biochemical and physiological tests were performed with these strains. Of the 72 isolates, 24 (41%) belonged to cluster I, 13 (46%) belonged to cluster II, 3 (43%) belonged to cluster III, 5 (29%) belonged to cluster IV, 5 (38%) belonged to cluster V, 10 (53%) belonged to cluster VI, and 12 (48%) belonged to cluster VII. Each isolate was grown on MRS agar for 48 h and Gram stained. Cell morphological characteristics were examined microscopically by using a Kontron image analyzer (Vidas, Darmstadt, Germany). Fermentation of carbohydrates was studied as described by Schillinger and Lücke (40). Isolates were tested to determine whether they fermented acetate, adonitol, arabinose, cellobiose, erythritol, fructose, galactose, glycerol, inositol, lactose, maltose, mannitol, mannose, melibiose, rhamnose, ribose, saccharose, sorbitol, sucrose, trehalose, and xylose. The terminal pH values of broth cultures were determined after 48 h of incubation in MRS broth at 25°C (15), and growth at pH 3.9 was determined in MRS broth (40). Tolerance to NaCl was examined by testing for growth in MRS broth containing 7 and 10% NaCl; the ability to grow at different temperatures was determined by growing the organisms in MRS broth after incubation at 4°C for 7 days and at 15 and 45°C for 3 days; and slime production was determined by using MRS agar containing sucrose instead of glucose (40). The presence of meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-DAP) in cell walls was determined as described by Keddie and Cure (20) by using paper chromatography (37). The configurations of lactic acid enantiomers were determined enzymatically by using d- and l-lactate dehydrogenase (Boehringer) (14). Production of gas from glucose, H2S contents, and hydrolysis of arginine were determined as described by Schillinger and Lücke (40).

FIG. 1.

Simplified dendrogram derived from whole-cell protein profiles of 180 lactic acid bacterial isolates from sorghum powder and corresponding fermented porridge and cooked fermented porridge samples. Electrophoretic patterns were analyzed by using GelManager software, version 1.5. Similarity patterns were calculated by using the Pearson product moment similarity coefficient, and clusters were delineated at an r value of 0.60.

AFLP analysis.

Genomic DNAs were extracted from 58 Lactobacillus plantarum strains (Fig. 1, cluster I) and 46 Leuconostoc mesenteroides strains (Fig. 1, clusters II and VI). Cultures were grown overnight in MRS broth (5 ml), and DNA was isolated from cells by using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (4) and was resuspended in 35 μl (final volume) of TE buffer. RNA was digested by incubating a DNA solution with 1 μl of DNase-free RNase (Boehringer) at 37°C for 1 h. The purity and concentration of the DNA were determined on 1% agarose gels by using lambda DNA (Boehringer) as the concentration standard. Pure DNA was stored at −20°C until it was used.

The AFLP reactions were performed with an AFLP Ligation and Pre-selective Amplification kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). DNA was cleaved with restriction enzymes EcoRI and Tru9I (MseI isoschizomer) and was ligated to the adapters by using T4 DNA ligase (Boehringer); the preparations were incubated at 37°C overnight in Eppendorf tubes containing 1 μl of T4 DNA ligase buffer, 0.5 μl of nuclease-free NaCl (0.5 M; BDH, Dorset, England), 0.5 μl of nuclease-free bovine serum albumin (10 mg/ml; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), and 1.6 μl of a master enzyme mixture. The master enzyme mixture was prepared immediately before use and contained 0.5 μl of EcoRI (10 U/μl), 0.1 μl of Tru9I (10 U/μl), and 1 μl of T4 DNA ligase (1 U/μl). Preselective amplification was carried out by using EcoRI and MseI primers with single 3′ A and 3′ C selective bases, respectively. A model 2400 Gene Amp PCR system (Perkin-Elmer) was used for PCR. The sequences of primers and adapters were not supplied by the manufacturer.

DNA fragments generated by PCR were separated on denaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels with 8 M ultrapure urea (ICN Biochemicals Inc., Aurora, Ohio). Glass plates were treated as described in the Promega manual (36), except that the short plate was treated with Bind Silane (Promega, Madison, Wis.) instead of SigmaCote. Aliquots (4 μl) of the PCR mixtures were mixed with equal volumes of loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA [pH 8], 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol), denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and snap cooled on ice before loading. Amplified fragments were separated at 55 W by using a model S2 sequencing gel electrophoresis apparatus (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and 1× TBE as the electrophoresis buffer. The lower-compartment buffer was supplemented with 0.5 M sodium acetate to prevent gel “frowning” (1). Molecular weight marker X (Boehringer) was included in every fourth track as a standard in order to normalize patterns in different gels. Gels were stained by using a modified silver staining method (3). The modifications included fixing in 12% acetic acid, staining with 1 g of silver nitrate per liter, and developing in a solution containing 0.5 ml of sodium thiosulfate (10 mg/ml) per liter and 2.5 ml of formaldehyde (37%) per liter.

The gels were air dried and scanned with a ScanJet IIcx scanner (Hewlett-Packard, Santa Clara, Calif.). The electrophoretic patterns were analyzed by using the software package GelManager, version 1.5 (Biosystematica). Levels of similarity between AFLP fingerprints were calculated by using the Dice coefficient (SD), which equaled the ratio of twice the number of bands shared by two patterns that were compared to the total number of bands in both patterns (5). Strains were clustered by using UPGMA (5), and clusters were delineated at SD levels of 0.70 (for L. plantarum strains) and 0.74 (for L. mesenteroides strains).

RESULTS

Total-soluble-protein profiles and biochemical and physiological characteristics.

Results of our analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3. All of the isolates utilized fructose and did not utilize adonitol, erythritol, inositol, or rhamnose. On the basis of a computerized numerical analysis of protein electrophoretic patterns, we grouped the isolates into seven major clusters (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Biochemical and physiological characteristics of 72 lactic acid bacterial isolates selected from clusters based on an analysis of electrophoretic profiles of total soluble proteins

| Biochemical or physiological characteristic | L. plantarum (n = 24)a | L. sake-L. curvatus(n = 12) | L. mesenteroides(n = 10) | L. mesenteroides(n = 13) | P. acidilactici(n = 5) | P. pentosaceus(n = 5) | L. lactis (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Rods | Rods | Coccoid rods | Coccoid rods | Cocci in tetrads | Cocci in tetrads | Cocci |

| Growth at: | |||||||

| 4°C | +b | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| 15°C | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| 45°C | + | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| pH 3.9 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Final pH | <4.0 | <4.0 | <4.0 | <4.0 | <4.0 | <4.0 | >4.0 |

| Growth in: | |||||||

| 7% NaCl | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 10% NaCl | − | + | − | − | ± | + | − |

| Gas production | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Dextran production | − | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Arginine test | − | + | − | − | + | − | + |

| Lactate isomer | dl | dl | d | d | dl | dl | l |

| m-DAP | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Utilization of: | |||||||

| Acetate | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Adonitol | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Arabinose | + | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Cellobiose | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| Erythritol | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Fructose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Galactose | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Glycerol | ± | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Inositol | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Lactose | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Maltose | + | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| Mannitol | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Mannose | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| Melibiose | + | ± | + | + | − | + | + |

| Ribose | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Rhamnose | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Saccharose | + | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| Sorbitol | + | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Sucrose | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Trehalose | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Xylose | − | − | + | + | + | − | − |

n, number of isolates.

+, positive; −, negative; ±, variable.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of lactic acid bacteria according to sample type and household, based on an analysis of total-soluble-protein profiles and biochemical and physiological tests

| Source | No. of strains (household distribution)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster I (L. plantarum) | Cluster II (L. mesenteroides) | Cluster III (L. lactis) | Cluster IV (P. pentosaceus) | Cluster V (P. acidilactici) | Cluster VI (L. mesenteroides) | Cluster VII (L. sake-L. curvatus) | |

| Sorghum powder | 20 (11/15)a | 0 | 3 (3/15) | 2 (1/15) | 8 (3/15) | 3 (3/15) | 7 (2/15) |

| Fermented porridge | 27 (13/15) | 23 (6/15) | 2 (1/15) | 11 (3/15) | 4 (2/15) | 13 (11/15) | 11 (4/15) |

| Cooked fermented porridge | 11 (4/15) | 5 (5/15) | 2 (1/15) | 4 (3/15) | 1 (1/15) | 3 (1/15) | 7 (3/15) |

| Total | 58 | 28 | 7 | 17 | 13 | 19 | 25 |

Number of households from which strains were obtained/number of households examined.

The largest cluster (cluster I) (Fig. 1) consisted of 58 L. plantarum strains, which were characterized by their rod-shaped cells, the presence of m-DAP in their cell walls, production of dl-lactate, fermentation of ribose, and an inability to utilize arginine (Table 2). The reference strain of L. plantarum (DSM 20174T) also was a member of this cluster. Of the 58 strains in this cluster, 20 were isolated from sorghum powder samples, 27 were isolated from fermented porridge samples, and 11 were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples (Table 3). The strains isolated from sorghum powder and fermented porridge samples were recovered most frequently and were obtained from 11 and 13 of the 15 households, respectively (Table 3). The 11 strains isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples were recovered from four households.

The second largest cluster (cluster II) (Fig. 1) consisted of 28 L. mesenteroides strains, all of which produced the d isomer of lactic acid, utilized acetate, produced dextran from sucrose, and were not able to produce ammonia from arginine (Table 2). A total of 23 of these strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from six households, whereas five strains were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples and were obtained from five households (Table 3). No strain in this cluster was isolated from sorghum powder samples.

Cluster III was the smallest cluster and consisted of seven Lactococcus lactis strains (Fig. 1), all of which had coccoid cells, produced the l isomer of lactic acid, were not able to produce gas from glucose, and could not utilize lactose. The terminal pH produced in MRS broth was more than 4.0 (Table 2). The reference strains L. lactis subsp. lactis DSM 20481 and L. lactis subsp. cremoris DSM 20069 were members of this cluster. Of the seven strains in this cluster, three were isolated from sorghum powder samples, two were isolated from fermented porridge samples, and two were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples (Table 3). The three strains isolated from sorghum powder samples were obtained from three households, whereas the four strains isolated from fermented and cooked fermented porridge samples were obtained from the same household (Table 3).

Cluster IV was designated a Pediococcus pentosaceus cluster and consisted of 17 strains (Fig. 1). The cells of these strains were coccoid and were arranged in pairs or tetrads. These strains utilized cellobiose, galactose, melibiose, and sorbitol and produced the dl isomer of lactic acid. The terminal pH produced in MRS broth after 48 h of incubation was less than 4.0 (Table 2). The cluster IV isolates grouped with the reference strain P. pentosaceus DSM 20366. Of the 17 P. pentosaceus strains in this cluster, 2 were isolated from sorghum powder and were obtained from one household, 11 were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from three households, and 4 were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples and were obtained from three households (Table 3).

Cluster V was designated a Pediococcus acidilactici cluster and consisted of 13 strains, including reference strain P. acidilactici DSM 20284 (Fig. 1). The cells of these isolates were coccoid and occurred in tetrads or pairs. The cluster V strains differed from the P. pentosaceus strains in that they hydrolyzed arginine and fermented xylose and arabinose but did not utilize sorbitol, melibiose, galactose, or cellobiose (Table 2). Eight of these strains were isolated from sorghum powder samples and were obtained from three households, whereas four strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from two households. One strain was isolated from a cooked fermented porridge sample (Table 3).

Cluster VI was another L. mesenteroides cluster and consisted of 19 strains (Fig. 1). These strains produced the d isomer of lactic acid and dextran from sucrose but no ammonia from arginine. They differed from the members of the first Leuconostoc cluster (cluster II) (Fig. 1) in that they utilized arabinose, lactose, ribose, and trehalose (Table 2). The cluster VI isolates grouped with reference strain L. mesenteroides DSM 20343T. Of the 19 strains in this cluster, 13 were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from 11 households, whereas 3 were isolated from sorghum powder and were obtained from three households. The remaining three strains were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples and were obtained from the same household (Table 3).

Cluster VII consisted of 25 Lactobacillus sake-Lactobacillus curvatus strains (Fig. 1). Cells of these strains were typically rod shaped and produced gas from glucose and the dl isomer of lactic acid. These strains did not contain m-DAP in their cell walls (Table 2). Eleven of these strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from four households, while seven strains were isolated from sorghum powder samples and were obtained from two households; the remaining seven strains were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples and were obtained from three households (Table 3).

There were 13 isolates that did not belong to any major cluster (Fig. 1). Although two of these isolates were very similar, the other isolates constituted a heterogeneous group along with seven of the reference strains, which were randomly distributed among them. No isolate grouped with Lactobacillus alimentarius DSM 20249T, Lactobacillus brevis DSM 20054T, Lactobacillus casei DSM 20011T, Lactobacillus coryniformis DSM 20001T, L. curvatus DSM 20019T, Lactobacillus confusus (Weissella confusa) DSM 20196T or Leuconostoc paramesenteroides (Weissella paramesenteroides) DSM 20288T (results not shown).

AFLP analysis.

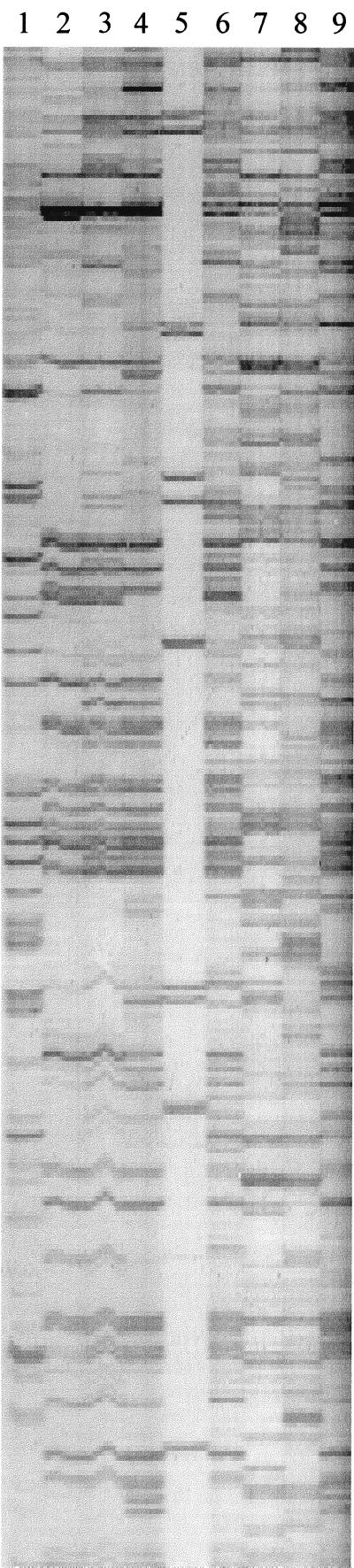

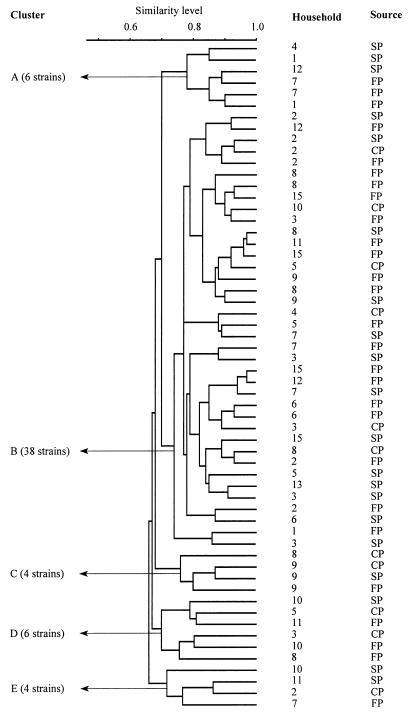

A representative silver-stained AFLP gel is shown in Fig. 2. Our analysis of the DNA electrophoretic patterns of the 58 L. plantarum strains resulted in five major clusters (Fig. 3 and Table 4). Cluster A consisted of six strains; three of these strains were isolated from sorghum powder samples and were obtained from three households (households 1, 4, and 12), and the other three strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from two households (households 1 and 7). Cluster B was the largest cluster, comprising 38 strains. Thirteen of these strains were isolated from sorghum powder samples and were obtained from nine households (households 2, 3, 5 through 9, 13, and 15), while nineteen strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from eleven households (households 1 through 3, 5, through 9, 11, 12, and 15) and six strains were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples and were obtained from six households (households 2 through 5, 8, and 10). Cluster C contained four strains, three of which were obtained from the same household (household 9) but were isolated from three different types of samples; the remaining strain was isolated from a cooked fermented porridge sample obtained from household 8. Cluster D was composed of six strains, one of which was isolated from a sorghum powder sample and was obtained from household 10; three strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from three households (households 8, 10, and 11), and two strains were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples obtained from households 3 and 5. Cluster E contained four strains, two of which were isolated from sorghum powder samples and were obtained from two households (households 10 and 11); one strain was isolated from a fermented porridge sample obtained from household 7, and one strain was isolated from a cooked fermented porridge sample obtained from household 2.

FIG. 2.

AFLP patterns of L. plantarum and L. mesenteroides strains isolated from fermented porridge. Lanes 1, 7, and 8, L. mesenteroides strains; lanes 2 through 4, 6, and 9, L. plantarum strains; lane 5, molecular weight marker X.

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram of 58 L. plantarum strains derived from an UPGMA of AFLP patterns. Levels of similarity between AFLP fingerprints were calculated by using SD, and clusters were delineated at an arbitrary SD level of 0.70. The sources of isolates are indicated as follows: SP, sorghum powder; FP, fermented porridge; and CP, cooked fermented porridge.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of 58 L. plantarum strains according to sample type and household, based on an AFLP analysis

| Source | No. of strains (household distribution)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | Cluster D | Cluster E | |

| Sorghum powder | 3 (3/15)a | 13 (9/15) | 1 (1/15) | 1 (1/15) | 2 (2/15) |

| Fermented porridge | 3 (2/15) | 19 (11/15) | 1 (1/15) | 3 (3/15) | 1 (1/15) |

| Cooked fermented porridge | 0 | 6 (6/15) | 2 (2/15) | 2 (2/15) | 1 (1/15) |

| Total | 6 | 38 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

Number of households from which strains were obtained/number of households examined.

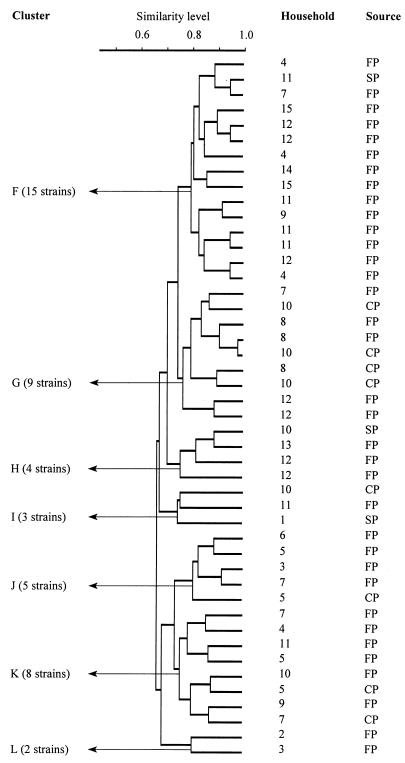

The 46 L. mesenteroides strains analyzed by using AFLP profiles grouped into five minor clusters and two major clusters (Fig. 4 and Table 5) that were similar to the two Leuconostoc clusters obtained after total-soluble-protein patterns were analyzed (Fig. 1). Cluster F was the largest cluster and contained 15 strains. Only one strain was isolated from sorghum powder (household 11), while 14 strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from seven households (households 4, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14, and 15). The second cluster (cluster G) comprised nine strains; five of these strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from three households (households 7, 8, and 12), and four were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples and were obtained from two households (households 8 and 10). The third cluster (cluster H) was composed of four strains, three of which were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from two households (households 12 and 13); the other strain was isolated from a sorghum powder sample obtained from household 10. The fourth cluster (cluster I) was composed of three strains, one from each type of sample. These strains were obtained from different households (households 1, 10, and 11). The fifth cluster (cluster J) comprised five strains; four of these strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from four households (households 3 and 5 through 7), and the remaining strain was isolated from a cooked fermented porridge sample obtained from household 5. The sixth cluster (cluster K) was composed of eight strains; six of these strains were isolated from fermented porridge samples and were obtained from six households (households 4, 5, 7, and 9 through 11), and the remaining two strains were isolated from cooked fermented porridge samples obtained from households 5 and 7. The last cluster (cluster L) consisted of two strains, both of which originated from fermented porridge samples obtained from households 2 and 3.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram of 46 L. mesenteroides strains derived from an UPGMA of AFLP patterns. Levels of similarity between AFLP fingerprints were calculated by using SD, and clusters were delineated at an arbitrary SD level of 0.74. The sources of isolates are indicated as follows: SP, sorghum powder; FP, fermented porridge; and CP, cooked fermented porridge.

TABLE 5.

Distribution of 46 L. mesenteroides strains according to sample type and household, based on an AFLP analysis

| Source | No. of strains (household distribution)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster F | Cluster G | Cluster H | Cluster I | Cluster J | Cluster K | Cluster L | |

| Sorghum powder | 1 (1/15)a | 0 | 1 (1/15) | 1 (1/15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fermented porridge | 14 (7/15) | 5 (3/15) | 3 (2/15) | 1 (1/15) | 4 (4/15) | 6 (6/15) | 2 (2/15) |

| Cooked fermented porridge | 0 | 4 (2/15) | 0 | 1 (1/15) | 1 (1/15) | 2 (2/15) | 0 |

| Total | 15 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 |

Number of households from which strains were obtained/number of households examined.

DISCUSSION

Characterization of lactic acid bacteria.

The bacterial populations in sorghum powder samples and corresponding fermented and cooked fermented porridge samples consisted of Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Pediococcus strains. Previous studies showed that naturally fermented cereal-based African foods are dominated by L. plantarum, Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus reuteri, L. mesenteroides, P. pentosaceus, and L. lactis strains (32, 38). The majority of the isolates characterized in this study belonged to the genera Lactobacillus (83 of the 180 isolates examined) and Leuconostoc (47 of the 180 isolates examined). The largest cluster obtained in the protein profile analysis (cluster I) (Fig. 1) consisted of L. plantarum strains, while L. mesenteroides strains grouped into two clusters (clusters II and VI) (Fig. 1), which may represent different subspecies of L. mesenteroides. These two species dominated the fermentation processes in this study. They have been isolated previously from a variety of food products and environmental sources and reportedly are two of the most dominant species during fermentation of sorghum-based infant-weaning foods (29, 31).

The third largest cluster identified in the protein profile analysis (cluster VII) (Fig. 1) was an L. curvatus-L. sake cluster. Members of this group belonged to the group of atypical streptobacteria which are phenotypically diverse and are usually distinguished from each other on the basis of fermentation of melibiose and arginine hydrolysis. L. curvatus is negative for both of these characteristics (23). Phenotypic characteristics of strains belonging to this cluster suggested that a mixture of the two species was present. In previous studies workers have described the phenotypic similarities of L. sake and L. curvatus (19) and the inability of biochemical tests and total-soluble-protein profiles to consistently differentiate between strains of these two species (13, 16).

Clusters IV and V (Fig. 1) consisted of strains belonging to the genus Pediococcus. Pediococci have often been found at low frequencies together with leuconostocs and lactobacilli on plant material and in various foods. They are also widely used as starter cultures in the fermentation of sausages and have been used to control food pathogens in vegetables (43). Pediococci have previously been isolated from fermented cereal gruels (22).

The smallest cluster (cluster III) (Fig. 1), which consisted of only seven strains, was an L. lactis cluster. The natural habitat of lactococci is milk, but L. lactis subsp. lactis has been isolated previously from plants, vegetables, and cereals (10, 39).

Household recovery frequencies.

The greater frequencies of recovery of L. plantarum, L. sake-L. curvatus, L. mesenteroides, and P. pentosaceus strains from fermented porridge samples than from sorghum powder samples suggested that these strains participated in the fermentation processes. By contrast, the frequencies of recovery of P. acidilactici and L. lactis strains from fermented porridge samples were lower than the frequencies of recovery from sorghum powder samples. This was probably due to the inability of the organisms to compete with other lactic acid bacterial species and to the inability of L. lactis strains to grow at pH values of less than 4.

The fact that L. plantarum strains were present in sorghum powder samples obtained from 73% of the households suggested that these strains were present in sorghum powder samples prior to household handling and processing and thus that sorghum powder is a natural habitat of L. plantarum. The low frequencies of recovery of L. lactis, L. sake-L. curvatus, L. mesenteroides, P. acidilactici, and P. pentosaceus strains from sorghum powder in households (Table 3) indicated that these organisms either were present at low levels in the powder and thus were not detected or were introduced through handling and processing at the household level. Members of these groups have typically been associated with foods, including vacuum-packaged meat and meat products and vacuum-packaged smoked and salted fish (6, 15). Members of the L. sake-L. curvatus group have also been reported to be responsible for spoilage of chill-stored vacuum-packaged meat products (46).

The isolation of lactic acid bacterial strains from cooked fermented porridge samples suggested that recontamination occurred, probably due to use of the same utensils, such as spoons, during the preparation and storage of the cooked fermented porridge samples. Recontamination of cooked samples, however, may also have resulted from strains present in households before the study was conducted, particularly since the storage containers used for sorghum powder samples were seldom washed before new sorghum powder was added. It is very unlikely that contaminating strains were strains that survived the cooking process since the cooking process was deemed sufficient to kill vegetative cells (24).

None of the households which we studied yielded a single-species population of lactic acid bacteria associated with sorghum samples after fermentation. It should be mentioned, however, that the processes from which the lactic acid bacteria were obtained were not studied over a sufficiently long period for natural selection to result in a stable microbiological population of lactic acid bacteria. Usually, single-species populations are established only after several cycles of the fermentation process (29), while in our case the samples were collected after the first cycle, which lasted 36 to 72 h.

AFLP analysis.

As a result of the highly selective and stringent PCR protocol used in the AFLP procedure, the discriminatory power of this technique is such that it is able to detect single point mutations in strains. However, slight variations in band width and mobility, as well as background intensities, may result in similarity levels that are less than 100% for strains that appear to be identical after AFLP patterns are analyzed visually. Thus, the similarity levels obtained in the present study are not absolute; nevertheless, they are useful for determining relationships among L. plantarum and L. mesenteroides strains, as shown in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively. The presence of a majority (66%) of the L. plantarum strains obtained from sorghum powder in one cluster (cluster B) (Fig. 4) suggested that this group was the dominant group in sorghum powder. High household recovery frequencies for strains belonging to this cluster (Table 4) suggested that the source of these strains was sorghum powder samples. By contrast, the remaining L. plantarum strains (34%) grouped in four small clusters, and their household recovery frequencies were low. This indicated that these organisms were not part of the normal flora of sorghum powder but may have been introduced at the household level.

One-third of the L. mesenteroides strains which we studied grouped in one cluster (cluster F) (Fig. 4), as determined by the AFLP analysis. All but one of the strains in this cluster were isolated from fermented porridge samples. These strains were recovered from 47% of the households, which suggests that they had a common origin, perhaps sorghum powder; however, because they were present in low numbers in the powder, they were not detected. The presence of the rest of the L. mesenteroides strains (two-thirds of the strains) in six small clusters and the fact these strains were recovered at low household frequencies could suggest that they were not part of the normal flora of sorghum powder but rather were introduced at the household level.

Conclusion.

In this study, members of several genera of lactic acid bacteria were recovered from sorghum powder and corresponding fermented and cooked fermented porridge. The dominant groups found in the fermented porridge samples were L. plantarum and L. mesenteroides. High household recovery frequencies and the results of an AFLP analysis of the majority of the L. plantarum strains suggested that these organisms originated from the sorghum powder. The AFLP analysis results also indicated that the majority of the L. mesenteroides strains did not have a common origin and thus were likely to have been introduced at the household level. The remainder of the L. mesenteroides strains, however, appeared to have had a common source, possibly sorghum powder, but they may not have been detected due to the low numbers present.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aarts H J M, van Lith L A J T, Keijer J. High-resolution genotyping of Salmonella strains by AFLP-fingerprinting. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998;26:131–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias C R, Verdonck L, Swings J, Garay E, Aznar R. Intraspecific differentiation of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes by amplified fragment length polymorphism and ribotyping. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2600–2606. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2600-2606.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassam B J, Caetano-Anollés G, Gresshoff P M. Fast and sensitive silver staining of DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1991;196:80–83. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90120-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickley J, Short J K, Mcdowell D G, Parkes H C. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of Listeria monocytogenes in diluted milk and reversal PCR inhibition caused by calcium ions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BioSystematica. GelManager for Windows version 1.5 user's manual. Devon, United Kingdom: BioSystematica; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Björkroth K J, Korkeala H J. Evaluation of Lactobacillus sake contamination in vacuum-packaged sliced cooked meat products by ribotyping. J Food Prot. 1996;59:398–401. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bragard C, Singer A, Alizadeh L, Vauterin H, Maraite H, Swings J. Xanthomonas translucens from small grains: diversity and phytopathological relevance. Phytopathology. 1997;87:1111–1117. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.11.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellanos M I, Chauvet A, Deschamps A, Barreau C. PCR methods for identification and specific detection of probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Curr Microbiol. 1996;33:100–103. doi: 10.1007/s002849900082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clerc A, Manceau C, Nesme X. Comparison of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA with amplified fragment length polymorphism to assess genetic diversity and genetic relatedness within genospecies III of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1180–1187. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1180-1187.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J. Antimicrobial potential of lactic acid bacteria. In: De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J, editors. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. New York, N.Y: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1994. pp. 91–141. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dicks L M T, Van Vuuren H J J, Dellaglio F. Taxonomy of Leuconostoc species, particularly Leuconostoc oenos, as revealed by numerical analysis of total soluble cell protein patterns, DNA base compositions, and DNA-DNA hybridizations. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dykes G, Cloete T E, von Holy A. Quantification of microbial populations associated with the manufacture of vacuum-packaged, smoked vienna sausages. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;13:239–248. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dykes G A, von Holy A. Taxonomy of lactic acid bacteria from spoiled, vacuum packaged Vienna sausages by total soluble protein profiles. J Basic Microbiol. 1993;33:169–177. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620330306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dykes G A, Brits T J, von Holy A. Numerical taxonomy and identification of lactic acid bacteria from spoiled, vacuum-packaged vienna sausages. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gancel F, Dzierszinski F, Tailliez R. Identification and characterisation of Lactobacillus species isolated from fillets of vacuum-packed smoked and salted herring (Clupea harengus) J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:722–728. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastings J W, Holzapfel W H. Numerical taxonomy of lactobacilli surviving radurization of meat. Int J Food Microbiol. 1987;4:33–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1987.tb02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huys G, Coopman R, Janssen P, Kersters K. High-resolution genotypic analysis of the genus Aeromonas by AFLP fingerprinting. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:572–580. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen P, Maquelin K, Coopman R, Tjernberg I, Bouvet P, Kersters K, Dijkshoorn L. Discrimination of Acinetobacter genomic species by AFLP fingerprinting. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1179–1187. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kagermeier-Callaway A, Lauer E. Lactobacillus sake Katagiri, Kitahara, and Fukami 1934 is the senior synonym for Lactobacillus bavaricus Stetter and Stetter 1980. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:398–399. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keddie R M, Cure G L. The cell wall composition and distribution of free mycolic acids in named strains of coryneform bacteria and in isolates from various natural sources. J Appl Bacteriol. 1977;42:229–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1977.tb00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keim P, Kalif A, Schupp J, Hill K, Travis S E, Richmond K, Adair D M, Hugh-Jones M, Kuske C R, Jackson P. Molecular evolution and diversity in Bacillus anthracis as detected by amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:818–824. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.818-824.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingamkono R, Sjögren E, Svanberg U, Kaijser B. Inhibition of different strains of enteropathogens in a lactic-fermenting cereal gruel. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;11:299–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00367103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein G, Dicks L M T, Pack A, Hack B, Zimmermann K, Dellaglio F, Reuter G. Amended descriptions of Lactobacillus sake (Katagiri, Kitahara, and Fukami) and Lactobacillus curvatus (Abo-Elnaga and Kandler): numerical classification revealed by protein fingerprinting and identification based on biochemical patterns and DNA-DNA hybridizations. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:367–376. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunene N F, Hastings J W, von Holy A. Bacterial populations associated with a sorghum-based fermented weaning cereal. Int J Food Microbiol. 1999;49:75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(99)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leisner J J, Greer G G, Stiles M E. Control of beef spoilage by a sulfide-producing Lactobacillus sake strain with bacteriocinogenic Leuconostoc gelidum UAL187 during anaerobic storage at 2°C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;61:2610–2614. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2610-2614.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorri W, Svanberg U. An overview of the use of fermented foods for child feeding in Tanzania. Ecol Food Nutr. 1994;34:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motarjemi Y, Nout M J R. Food fermentation: a safety and nutritional assessment. Bull W H O. 1996;74:553–559. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nes I F, Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Brurberg M B, Eijsink V, Holo H. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:113–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00395929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nout M J R. Ecology of accelerated natural lactic fermentation of sorghum-based infant food formulas. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:217–224. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90072-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nout M J R, Beernink G, Bonants-van Laarhoven T M G. Growth of Bacillus cereus in soybean tempeh. Int J Food Microbiol. 1987;4:293–301. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsen A, Halm M, Jakobsen M. The antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria from fermented maize (kenkey) and their interactions during fermentation. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:506–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyewole O B. Fermentation: assessment and research. Report of a joint FAO/WHO workshop on fermentation as a household technology to improve food safety. WHO/FNU/FOS/96.1. Geneva, Switzerland: Food Safety Unit, Division of Food and Nutrition, World Health Organization; 1995. Lactic fermented foods in Africa and their benefits; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patarata L, Pimentel M S, Pot B, Kersters K, Faia A M. Identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Portuguese wines and musts by SDS-PAGE. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:288–293. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pattison T, Geornaras I, von Holy A. Microbial populations associated with commercially produced South African sorghum beer as determined by conventional and PetrifilmTM plating. J Food Microbiol. 1998;43:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pot B, Hertel C, Ludwig W, Descheemaeker P, Kersters K, Schleifer K H. Identification and classification of Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. gasseri and L. johnsonii strains by SDS-PAGE and rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe hybridization. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:513–517. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-3-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Promega. Technical manual. SILVER SEQUENCETM DNA sequencing system. Madison, Wis: Promega Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhuland L E, Work E, Denman R F, Hoare D S. The behaviour of the isomers of α,ɛ-diaminopimelic acid on paper chromatograms. J Anal Chem Soc. 1955;77:4844–4846. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rombouts F M, Nout M J R. Microbial fermentation in the production of plant foods. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:108S–117S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salama M S, Musafija-Jeknic T, Sandine W E, Giovannoni S J. An ecological study of lactic acid bacteria: isolation of new strains of Lactococcus including Lactococcus lactis subspecies cremoris. J Dairy Sci. 1995;78:1004–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schillinger U, Lücke F K. Identification of lactobacilli from meat and meat products. Food Microbiol. 1987;4:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stiles M E, Holzapfel W H. Lactic acid bacteria of foods and their current taxonomy. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;36:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(96)01233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vandamme P, Pot B, Gillis M, De Vos P, Kersters K, Swings J. Polyphasic taxonomy, a consensus approach to bacterial systematics. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:407–438. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.407-438.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vescovo M, Torriani S, Orsi C, Macchiarolo F, Scolari G. Application of antimicrobial producing lactic acid bacteria to control pathogens in ready-to-use vegetables. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb04487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogel R F, Lohmann M, Nguyen M, Weller A N, Hammes W P. Molecular characterization of Lactobacillus curvatus and Lactobacillus sake isolated from sauerkraut and their application in sausage fermentations. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel R F, Böcker G, Stolz P, Ehrmann M, Fanta D, Ludwig W, Pot B, Kersters K, Schleifer K H, Hammes W P. Identification of lactobacilli from sourdough and description of Lactobacillus pontis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:223–229. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-2-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Holy A, Cloete T E, Holzapfel W H. Quantification and characterisation of microbial populations associated with spoiled, vacuum-packed Vienna sausages. Food Microbiol. 1991;8:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, Van De Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot B, Peterman J, Kuiper M, Zabeau M. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]