Abstract

Genetic alterations in FGF/FGFR pathway are infrequent in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), with rare cases of quadruple wildtype GISTs harboring FGFR1 gene fusions and mutations. Additionally, FGF/FGFR overexpression was shown to promote drug resistance to kinase inhibitors in GISTs. However, FGFR gene fusions have not been directly implicated as a mechanism of drug resistance in GISTs. Herein, we report a patient presenting with a primary small bowel spindle cell GIST and concurrent peritoneal and liver metastases displaying an imatinib-sensitive KIT exon 11 in-frame deletion. After an initial 9-month benefit to imatinib, the patient experienced intraabdominal peritoneal recurrence owing to secondary KIT exon 13 missense mutation and FGFR4 amplification. Despite several additional rounds of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), the patient’s disease progressed after 2 years and presented with multiple peritoneal and liver metastases, including one pericolonic mass harboring secondary KIT exon 18 missense mutation, and a concurrent transverse colonic mass with a FGFR2::TACC2 fusion and AKT2 amplification. All tumors, including primary and recurrent masses, harbored an MGA c.7272T>G (p.Y2424*) nonsense mutation and CDKN2A/CDKN2B/MTAP deletions. The transcolonic mass showed elevated mitotic count (18/10 HPF), as well as significant decrease in CD117 and DOG1 expression, in contrast to all the other resistant nodules that displayed diffuse and strong CD117 and DOG1 immunostaining. The FGFR2::TACC2 fusion resulted from a 742 kb intrachromosomal inversion at the chr10q26.3 locus, leading to a fusion between exons 1–17 of FGFR2 and exons 7–17 TACC2, which preserves the extracellular and protein tyrosine kinase domains of FGFR2. We present the first report of a multi-drug resistant GIST patient who developed an FGFR2 gene fusion as a secondary genetic event to the selective pressure of various TKIs. This case also highlights the heterogeneous escape mechanisms to targeted therapy across various tumor nodules, spanning from both KIT-dependent and KIT-independent off-target activation pathways.

Keywords: FGFR2, gene fusion, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, drug resistance, TKI, KIT

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a mesenchymal neoplasm that can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, with approximately 54% arising in the stomach, 30% in the small bowel, 5% in the colon and rectum, and 1% in the esophagus.1 Most GISTs harbor activating gain-of-function KIT (75%) exon 11 or exon 9, or PDGFRA (10%) exon 18 mutations.2,3 A subset of GISTs (5–10%) is characterized by succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) deficiencies, commonly in pediatric and young adult GISTs, either via SDHA/SDHB/SDHC/SDHD mutations or SDHC promoter methylation.4,5 Most of the remaining GISTs harbor drivers in the RAS pathway, including inactivating mutations in NF1 and activating mutations in BRAF.6–8 GISTs lacking any of the aforementioned four driver categories are defined as “quadruple” wildtype (WT) GISTs. In rare cases of quadruple WT GISTs, FGFR1 gene fusions and mutations have been reported as primary drivers.9,10

In mutant KIT-driven GISTs, the most common mechanism of drug resistance to imatinib is the development of secondary KIT exon 13 (ATP-binding pocket) or exon 17/18 (kinase activation loop) mutations.11 In rare cases without secondary KIT mutations, upregulation of the FGFR ligands FGF2/3/4 and downstream crosstalk between the FGFR and KIT/PDGFRA signaling pathways have been reported to mediate TKI resistance in GISTs.12–17 We present the first report of a multi-drug resistant GIST patient who developed a number of escape mechanisms to TKI therapies, including a KIT-independent FGFR2 gene fusion as a secondary genetic event.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohort

Clinical data, including age, sex, and anatomic site were retrieved from pathology reports. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides from resection specimens were rereviewed. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Targeted RNA Sequencing

Detailed descriptions of MSK-Fusion, an amplicon-based targeted RNA NGS assay using the Archer™ FusionPlex™ standard protocol, were described previously.18 Briefly, RNA is extracted from tumor formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded material followed by cDNA synthesis. cDNA libraries were made using the Archer™ FusionPlex™ standard protocol. Fusion unidirectional GSPs have been designed to target specific exons in 62 genes known to be involved in chromosomal rearrangements based on current literature. The final targeted amplicons are ready for 2×150bp sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer. FASTQ files are automatically generated using the MiSeq reporter software (Version 2.6.2.3) and analyzed using the Archer™ analysis software (Version 5.0.4). Each fusion call should be supported with a minimum of 5 unique reads and a minimum of 3 reads with unique start sites.

DNA Sequencing

Detailed descriptions of MSK-IMPACT workflow and data analysis, a hybridization capture-based targeted DNA NGS assay for solid tumor were described previously.19 Deletions and amplifications are defined as copy number log2 fold change < −2.0 and > 2.0, respectively; while copy number losses and gains are defined as copy number log2 fold change between −1.0 and −2.0 and between 1.0 and 2.0, respectively.

Results

Clinical summary

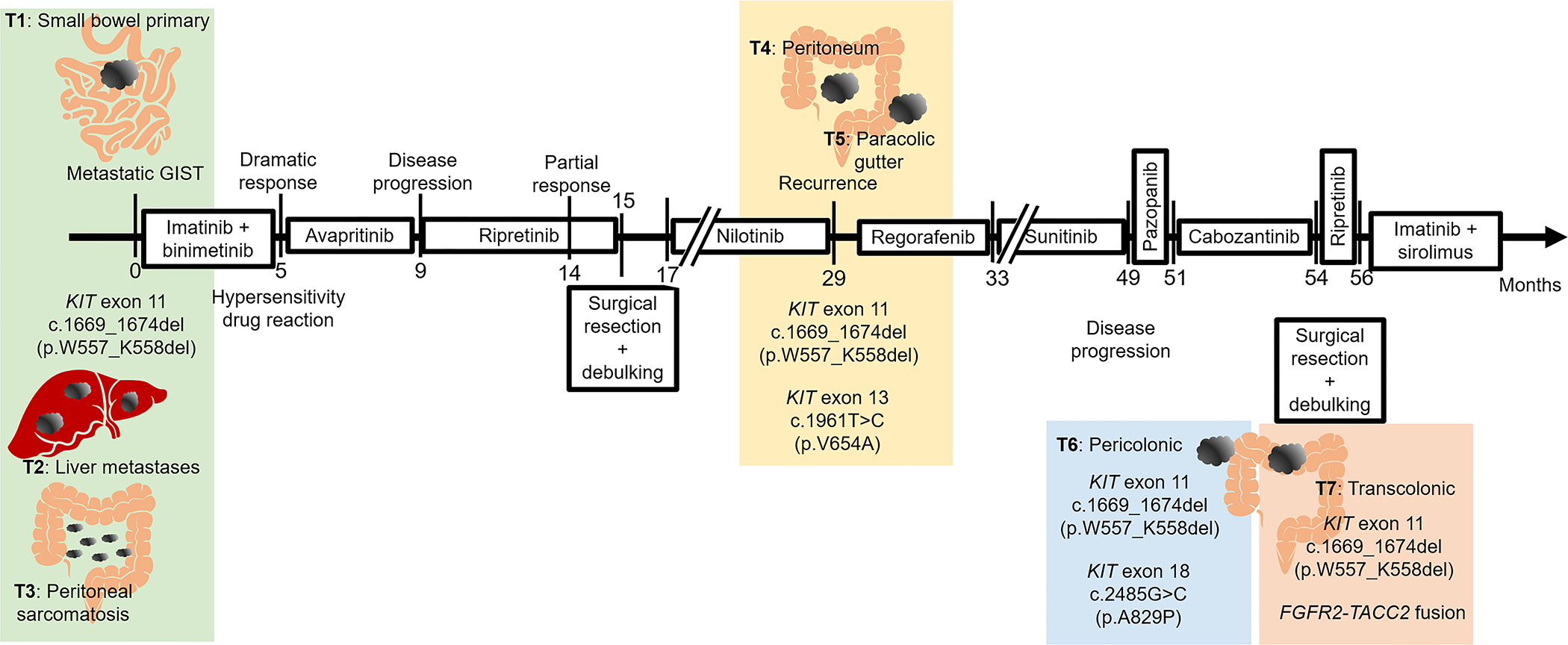

The detailed and complex clinical course of the patient is summarized in Figure 1. The patient is a 54-year-old male who presented with abdominal pain. CT abdomen revealed a dominant 19.5 cm lower abdominal mass arising from the small bowel (T1), 3 liver metastases [largest mass 3.2 cm (T2)] and peritoneal sarcomatosis (T3). After biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of GIST, the patient enrolled onto an imatinib and binimetinib combination phase II clinical trial (NCT01991379) for 5 months with dramatic clinicoradiologic response. However, he was switched to avapritinib due to drug toxicity, and his disease progressed after 4 months. He was put on ripretinib with partial response after 5 months and discontinued treatment due to cardiac toxicity and underwent surgical resection of the abdominal mass plus debulking. Thereafter, he was on nilotinib and presented with recurrence [T4: peritoneal mass; T5: paracolic mass] after one year. He was then treated with regorafenib followed by sunitinib, and his disease progressed after close to 2 years. He was switched to pazopanib with disease progression and then to cabozantinib, after which he underwent a second round of surgical resection and debulking of recurrent pericolonic (T6), transverse colon (T7), and liver tumors. He has since then been treated with another trial of ripretinib and then imatinib and sirolimus, being alive with disease 60 months since diagnosis.

Figure 1. Clinical course.

Schematic diagram illustrating disease course, targeted therapeutic regimens, and disease progression. Numbers on horizontal arrow indicate number of months since initial presentation (month 0). Shaded colored rectangular boxes indicate groups of one or more tumors biopsied/resected concurrently that shared the same KIT driver mutation and secondary KIT mutations or secondary translocation.

Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical features

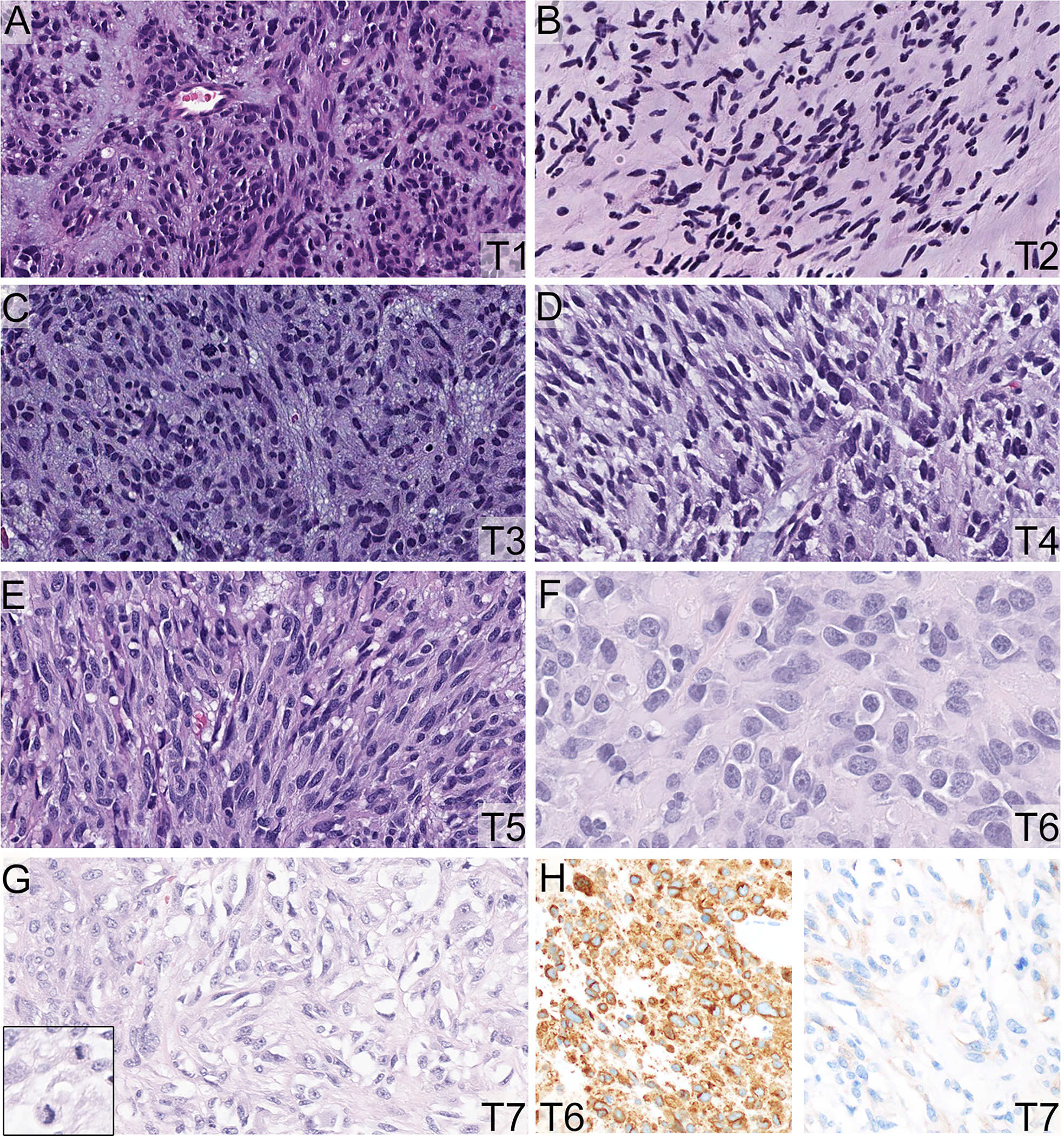

Microscopically, the GIST nodules (T1-T5) were spindle cell type and composed of fascicles of uniform spindle cells with ovoid to fusiform nuclei, open chromatin, small nucleoli, and a moderate amount of eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A–E). Tumor cells were diffusely and strongly positive for DOG1 and CD117. Interestingly, the pericolonic (T6) and transcolonic masses (T7) showed mixed spindled and epithelioid cytomorphology, and the tumor cells in T7 displayed increased mitotic count (Figure 2F,G, Supplementary Table 1). In contrast to the strong and uniform expression of CD117 and DOG1 in T6 (and T1-T5), there was extensive loss of CD117 and DOG1 immunoreactivity in T7 (Figure 2H) despite full cell viability.

Figure 2. Morphologic and immunohistochemical findings (T1-T7).

A-E. The GISTs (T1-T5) were spindle cell type and composed of fascicles of uniform spindle cells with ovoid to fusiform nuclei, open chromatin, small nucleoli, and moderate amount of eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm (200X). F-G. The pericolonic (T6) tumor showed more prominent epithelioid cytomorphology (F, 400X). The transverse colonic mass (T7) displayed prominent epithelioid cytomorphology with increased mitotic activity (G, 400X). A-G: Hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200X. There was extensive loss of CD117 immunoreactivity in T7 in comparison to the other tumors, including T6 (H, 200X).

Primary and secondary genetic alterations

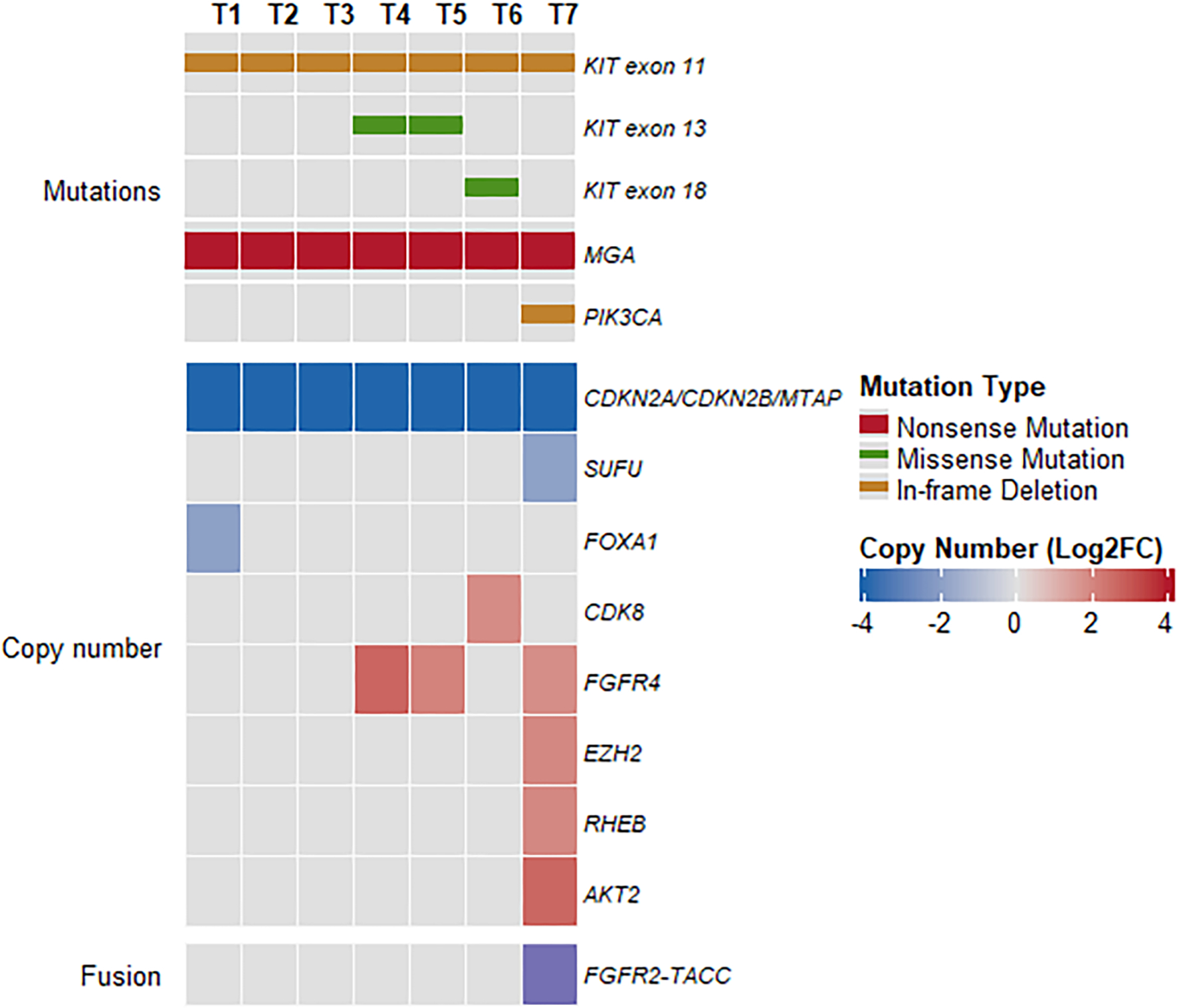

A targeted DNA sequencing panel (MSK-IMPACT) was performed on the initial and recurrent GISTs. The initial small bowel GIST (T1), as well as the liver (T2) and peritoneal metastases (T3), harbor KIT (NM_000222) exon 11 in-frame deletion (c.1669_1674delTGGAAG, p.W557_K558del). The subsequent peritoneal (T4) and paracolic (T5) recurrent GISTs developed a secondary KIT exon 13 c.1961T>C (p.V654A) missense mutation, as well as concurrent FGFR4 amplification. On the other hand, the most recent recurrent/metastatic pericolonic mass (T6) had the primary KIT exon 11 mutation and a secondary KIT exon 18 c.2485G>C (p.A829P) missense mutation (in the absence of KIT exon 13 mutations). Interestingly, the transverse colonic mass (T7) harbored the primary KIT exon 11 mutation, an FGFR2::TACC2 fusion (see below), as well as PIK3CA c.318_329del (p.N107_E110del) in-frame deletion and AKT2 amplification. All tumors (T1-T7) also harbored an MGA c.7272T>G (p.Y2424*) nonsense mutation and CDKN2A/CDKN2B/MTAP deletions (Figure 3). Additional copy number gains and losses are depicted in Figure 3 but not described here in detail.

Figure 3. Primary and secondary genomic alterations identified by MSK-IMPACT.

Heatmap and Oncoprint showing primary and secondary KIT mutations, co-occurring mutations, copy number alterations, and fusion in tumors T1-T7. Only OncoKB mutations and copy number alterations are included.

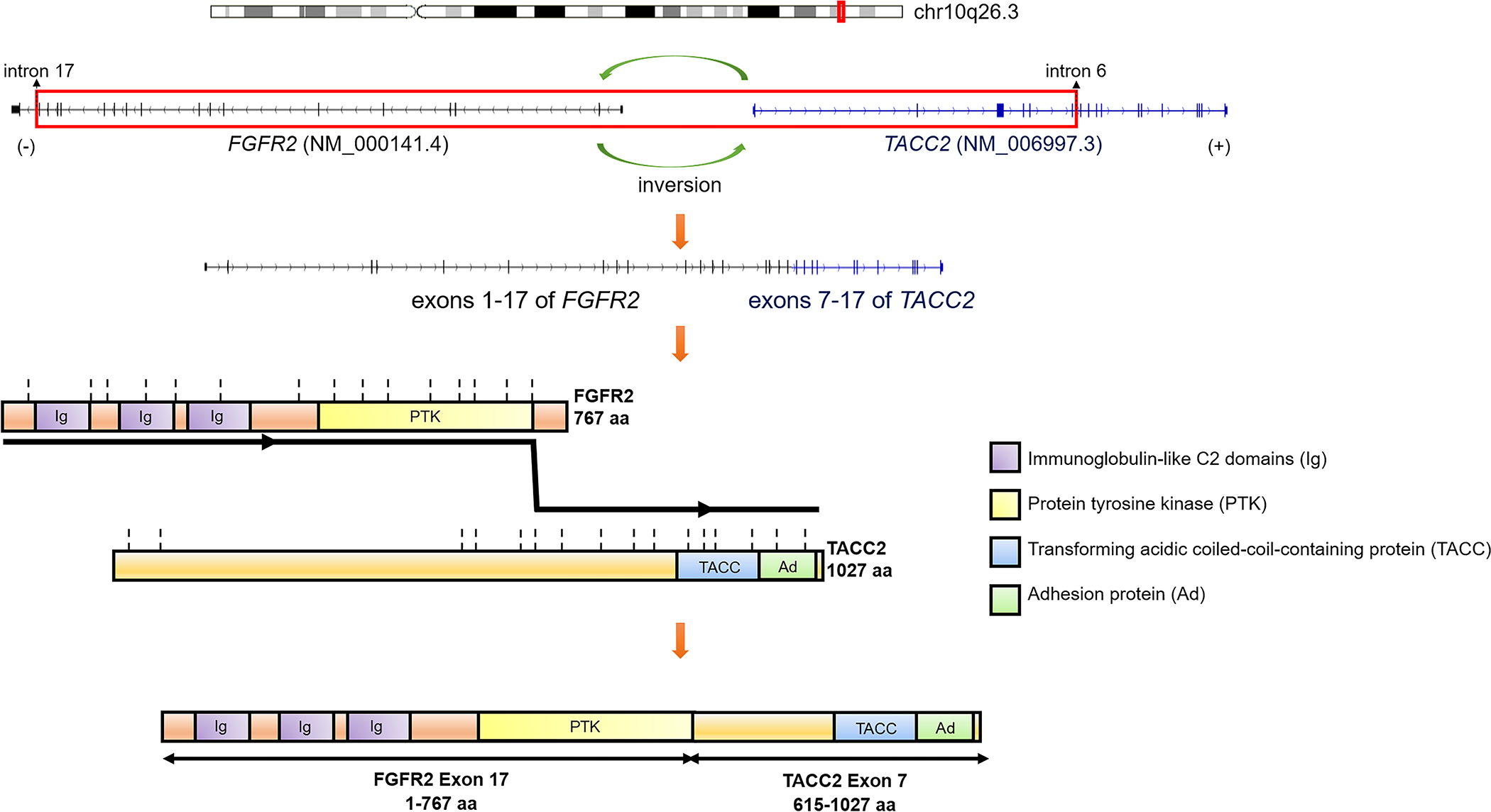

FGFR2::TACC2 fusion transcript

In T7, MSK-IMPACT detected a 742 kb (742,073 bp) inversion on chr10q26.3 with breakpoints located on intron 17 of FGFR2 (−) and intron 6 of TACC2 (+), resulting in a gene fusion between exons 1–17 of FGFR2 [NM_000141.4] and exons 7–17 of TACC2 [NM_006997.3]. A targeted RNA sequencing MSK-Fusion panel (Archer) confirmed an in-frame FGFR2::TACC2 fusion transcript. In the predicted chimeric protein product, the extracellular immunoglobulin (Ig)-like C2 and protein tyrosine kinase domains of FGFR2 are fused to the transforming acidic coiled-coil-containing (TACC) and adhesion protein domains of TACC2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Schematic of predicted fusion proteins encoded by gene fusions.

The fusion is a result of an inversion of the DNA fragment between intron 17 of FGFR2 [NM_000141.4] at chr10:123243187 and intron 6 of TACC2 [NM_006997.3] at chr10:123985260, as detected by DNA-seq. This results in an RNA chimeric transcript fusing exons 1–17 of FGFR2 to exons 7–17 of TACC2 with the chromosomal breakpoint chr10:123243212(−)::chr10:123985881(+), as detected by RNA-seq. The chimeric protein products are predicted to be in-frame. Vertical dotted lines represent exon boundaries. Abbreviations: aa, amino acids.

Discussion

Under selective pressure from imatinib treatment, GISTs are known to develop polyclonal evolution characterized by heterogenous secondary KIT mutations.20 The heterogeneity of KIT mutations account for the partial and differential sensitivity to TKIs.21 For example, the exon 13 p.V654A and exon 18 p.A829P missense mutations are known secondary KIT mutations that confer resistance to imatinib.21,22 Consistent with this phenomenon, the recurrent/metastatic tumors that developed over different time points in this case acquired different secondary KIT mutations, including KIT exon 13 and KIT exon 18 mutations. In fact, sunitinib was added to regorafenib due to the development of secondary KIT exon 13 mutation after the first disease progression. Interestingly, one of the recurrent nodules developed an FGFR2 gene fusion as a resistance mechanism.

The four main fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs): FGFR 1–4, are receptor tyrosine kinases each with different ligand binding specificity and affinity to fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), a large family of structurally related signaling molecules. Upon ligand binding to their extracellular domains, FGFRs undergo homo- or hetero-dimerization and auto- or trans-phosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain. This activation of FGFRs is coupled to downstream signaling pathways including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathways.22

FGF/FGFR alterations have been reported as primary drivers in rare cases of quadruple WT GISTs: three cases with FGFR1 gene fusions—2 FGFR1::TACC1, 1 FGFR1::HOOK3,9 two cases with FGFR1 mutations—1 FGFR1 K656E,9 1 FGFR1 N546K,10 and 6 cases with FGF4 overexpression.24 In the cases with FGFR1 gene fusions, the FGFR1 is the 5’ gene and the breakpoint is located in exons 17–19, thus preserving the extracellular Ig-like and intracellular tyrosine kinase domains, similar to the FGFR2 fusion in the current study. FGFR2 fusions, including FGFR2::TACC2, have also been described in approximately 15% of cholangiocarcinomas.25,26 FGFR3::TACC3 fusions have been seen in glioblastoma, bladder cancer, and lung cancer.26–29 In the cases with FGF4 overexpression, a recurrent focal gain in 11q13.3, which leads to FGF3/FGF4 duplication, was associated with overexpression of FGF4 at both mRNA and protein levels, and in turn activates FGFR1 in GIST.24 The two FGFR1 missense mutations, N546K and K656E, are both hotspot activating mutations in the protein tyrosine kinase domains seen frequently in solid tumors, particularly in gliomas.30 Further, Li et al examined the transcriptional profiles of 90 primary GIST samples (driver status unknown) and reported FGF2 and FGFR1 mRNA overexpression relative to > 30,000 non GIST neoplasms of various histotypes.14

Other rare cases of primary fusion driver events in quadruple WT GISTs included two cases of ETV6::NTRK3, reported separately and at least one being diffusely positive for CD117.9,31 Recently, we reported two cases of BRAF fusion-driven primary GISTs that showed weak to complete loss of KIT but preserved DOG1 immunoreactivity.32 Our case is remarkable in that both KIT and DOG1 showed markedly diminished immunoreactivity, and could present a significant diagnostic pitfall in the absence of molecular evidence of GIST drivers.

In mutant KIT-driven GISTs, the FGFR signaling pathway has been implicated as mechanisms of imatinib resistance in tumors lacking secondary KIT mutations.13,16,17 Activation of FGF signaling diminished imatinib-mediated suppression of MAPK signaling and cell proliferation, and combination of KIT and FGFR inhibition led to increased drug efficacy in in vitro and in vivo preclinical models.14 Increased FGF2 protein expression was seen in imatinib-resistant GIST patients, and addition of FGF2, the ligand for FGFR3, restored KIT phosphorylation during imatinib treatment. The underlying mechanism is likely driven by a signaling crosstalk between KIT and FGFR3 that activated the MAPK pathway to promote imatinib resistance.12 Supporting this observation, inhibition of FGF/FGFR signaling has been shown to resensitize GIST to imatinib in preclinical models.33 On the other hand, in SDH-deficient GISTs, global hypermethylation consequent to SDH loss disrupts CTCF-mediated insulation of the FGF3/FGF4 locus, thus leading to aberrant upregulation of FGF3 and FGF4.15 In parallel, in the current study, subsequent to treatment with imatinib + binimetinib, avapritinib and ripretinib, in addition to the development of a secondary KIT mutation, the patient demonstrated FGFR4 amplification in his first disease progression (T4 and T5), which likely arose as yet another mechanism of TKI resistance.

The FGFR2::TACC2 fusion in the TKI-resistant GIST in the current study is the first report of an FGFR fusion as a mechanism of drug resistance in GISTs. Interestingly, the primary genotype of this GIST, which was maintained throughout the clinical course, included a KIT imatinib-sensitive exon 11 deletion accompanied by CDKN2A/CDKN2B/MTAP deletion and MGA loss-of-function mutation (Figure 4). Thus, CDKN2A/CDKN2B/MTAP deletion and MGA loss-of-function mutation likely represent primary alterations associated with risk of malignant transformation and are independent of TKI sensitivity or selection pressure. Supporting this hypothesis, homozygous deletion of the CDKN2A/CDKN2B/MTAP 9p21 locus has been reported as a poor prognosticator in GISTs,34 regardless of the response status to TKI.

The emerging role of the FGF/FGFR signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of GISTs raises the potential of using kinase inhibitors targeting the FGF/FGFR signaling pathway in the treatment of GISTs.17 Both FGFR-specific and multi-kinase inhibitors are either in clinical trials or have been approved for the treatment of multiple cancers.35 Examples of multi-kinase inhibitors that also target FGFR and have been tested in GISTs include regorafenib, dovitinib, masitinib, ponatinib, and pazopanib.36–45 On the other hand, FGFR kinase-specific inhibitors include erdafitinib, infigratinib (BGJ398), and pemigatinib.35 Of these, erdafitinib is FDA-approved for treatment of patients with urothelial cancers with FGFR2 or FGFR3 alterations;46 infigratinib and pemigatinib are FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 fusions.47 The only selective FGFR kinase inhibitor that has been tested in GISTs so far is infigratinib, a FGFR1-4 inhibitor, along with imatinib in patients with imatinib-refractory advanced GISTs.48 The clinical response was limited to stable disease as the best response observed. However, the population in this study included heavily pre-treated KIT-mutant patients, irresponsive of molecular alterations. It would be interesting to see the efficacy of selective FGFR inhibitors in GISTs with proven FGF/FGFR molecular alterations.

In the majority of cases, mechanisms of resistance in GIST are remarkably on target through the development of secondary site mutations in the same oncogene (KIT),49 or less frequently, due to gene amplification of the same receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT).50,51 Of the TKIs that our patient has received, regorafenib and pazopanib also exhibit FGFR kinase inhibitory activity. Subsequent to regorafenib followed by sunitinib and then pazopanib treatment, the patient experienced his second disease progression (Figure 1): one nodule harbored KIT exon 18 mutation, which is sensitive to regorafenib but resistant to sunitinib,51 and another nodule harbored a FGFR2::TACC2 fusion. This raises the possibility that exposure to regorafenib led to at least initial suppression of the FGFR4 amplification-mediated drug resistance, and subsequent development of the FGFR2 fusion as an on target rather than off target mechanism of escape from FGFR inhibition. A case report of acquired resistance to FGFR inhibitor in an FGFR2-amplified gastric cancer via the emergence of a FGFR2::ACSL5 fusion supports this hypothesis.52 The selective losses of KIT and DOG1 expression in the nodule with FGFR2 gene fusion suggests a KIT-independent mechanism of resistance. Additional instances of KIT-independent mechanisms of TKI failure include the development of a KIT-negative dedifferentiated component driven by genomic instability, as indicated by loss of heterozygosity of KIT and, in rare cases, development of a KRAS G12V mutation or a BRAF V600E mutation.6,53

In conclusion, we present the first report of a multi-drug resistant GIST that developed a FGFR2 gene fusion as a secondary genetic event and mechanism of resistance to TKI-treatment. This phenomenon is analogous to acquired ALK and RET gene fusions as mechanisms of resistance to osimertinib in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma.54 These findings emphasize the clinical importance of serial molecular profiling encompassing mutations and gene fusions of concurrent tumors in the setting of advance GIST resistance to TKI treatment. Our results unravel the heterogeneous mechanisms of escape to various target inhibitors, which include KIT dependent (secondary KIT mutations) as well as KIT-independent (fusion in a different kinase, such as FGFR2) pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the MSK-ARCHER team at MSKCC for their excellent technical support.

Supported by: P50 CA 140146-01 (SS, CRA, PC, WT), P50 CA217694 (SS, CRA, PC, WT), P30 CA008748 (SS, CRA, PC, WT), Kristin Ann Carr Foundation (CRA), GIST Cancer Research Fund (CRA, PC), Cycle for Survival (CRA).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

WT reports personal fees from Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Mundipharma, C4 Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Blueprint, Agios Pharmaceuticals, NanoCarrier, Deciphera, Adcendo, Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Kowa, Servier, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Epizyme, Cogent, Medpacto, Foghorn Therapeutics. In addition, WT holds patents in companion diagnostics for CDK4 inhibitors. He serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Certis Oncology Solutions and Innova Therapeutics. He reports stock ownership for Atropos Therapeutics, and Innova Therapeutics.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1.Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299(5607):708–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oudijk L, Gaal J, Korpershoek E, et al. SDHA mutations in adult and pediatric wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2013(3);26:456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Killian JK, Miettinen M, Walker RL, et al. Recurrent epimutation of SDHC in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Sci Transl Med. 2014(268);6:268ra177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agaram NP, Wong GC, Guo T, et al. Novel V600E BRAF mutations in imatinib-naive and imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(10):853–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasparotto D, Rossi S, Polano M, et al. Quadruple-Negative GIST Is a Sentinel for Unrecognized Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(1):273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boikos SA, Pappo AS, Killian JK, et al. Molecular Subtypes of KIT/PDGFRA Wild-Type Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: A Report From the National Institutes of Health Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Clinic. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(7):922–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi E, Chmielecki J, Tang CM, et al. FGFR1 and NTRK3 actionable alterations in “Wild-Type” gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pantaleo MA, Urbini M, Indio V, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis Identifies MEN1 and MAX Mutations and a Neuroendocrine-Like Molecular Heterogeneity in Quadruple WT GIST. Mol Cancer Res. 2017;15(5):553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonescu CR, Besmer P, Guo T, et al. Acquired resistance to imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor occurs through secondary gene mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(11):4182–4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Javidi-Sharifi N, Traer E, Martinez J, et al. Crosstalk between KIT and FGFR3 Promotes Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Cell Growth and Drug Resistance. Cancer Res. 2015;75(5):880–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boichuk S, Galembikova A, Dunaev P, Valeeva E, Shagimardanova E, Gusev O, Khaiboullina S. A Novel Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Switch Promotes Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Drug Resistance. Molecules. 2017; 22(12):2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Huynh H, Li X, et al. FGFR-Mediated Reactivation of MAPK Signaling Attenuates Antitumor Effects of Imatinib in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(4):438–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flavahan WA, Drier Y, Johnstone SE, et al. Altered chromosomal topology drives oncogenic programs in SDH-deficient GISTs. Nature. 2019;575(7781):229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Napolitano A, Ostler AE, Jones RL, Huang PH. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR) Signaling in GIST and Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Cells. 2021;10(6):1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astolfi A, Pantaleo MA, Indio V, Urbini M, Nannini M. The Emerging Role of the FGF/FGFR Pathway in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benayed R, Offin M, Mullaney K, et al. High Yield of RNA Sequencing for Targetable Kinase Fusions in Lung Adenocarcinomas with No Mitogenic Driver Alteration Detected by DNA Sequencing and Low Tumor Mutation Burden. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(15):4712–4722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23(8):703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardelmann E, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Pauls K, et al. Polyclonal evolution of multiple secondary KIT mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors under treatment with imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(6):1743–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano C, Mariño-Enríquez A, Tao DL, et al. Complementary activity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors against secondary kit mutations in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(6):612–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinrich MC, Maki RG, Corless CL, et al. Primary and secondary kinase genotypes correlate with the biological and clinical activity of sunitinib in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5352–5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015;4(3):215–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbini M, Indio V, Tarantino G, Ravegnini G, Angelini S, Nannini M, et al. Gain of FGF4 is a frequent event in KIT/PDGFRA/SDH/RAS-P WT GIST. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019;58(9):636–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arai Y, Totoki Y, Hosoda F, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 tyrosine kinase fusions define a unique molecular subtype of cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1427–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu YM, Su F, Kalyana-Sundaram S, et al. Identification of targetable FGFR gene fusions in diverse cancers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(6):636–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Wang L, Li Y, et al. FGFR1/3 tyrosine kinase fusions define a unique molecular subtype of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(15):4107–4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh D, Chan JM, Zoppoli P, et al. Transforming fusions of FGFR and TACC genes in human glioblastoma. Science. 2012;337(6099):1231–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Luca A, Esposito Abate R, Rachiglio AM, et al. FGFR Fusions in Cancer: From Diagnostic Approaches to Therapeutic Intervention. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura IT, Kohsaka S, Ikegami M, et al. Comprehensive functional evaluation of variants of fibroblast growth factor receptor genes in cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenca M, Rossi S, Polano M, et al. Transcriptome sequencing identifies ETV6-NTRK3 as a gene fusion involved in GIST. J Pathol. 2016;238(4):543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torrence D, Xie Z, Zhang L, Chi P, Antonescu CR. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors with BRAF gene fusions. A report of two cases showing low or absent KIT expression resulting in diagnostic pitfalls. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2021;60(12):789–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boichuk S, Galembikova A, Dunaev P, Micheeva E, Valeeva E, Novikova M, Khromova N, Kopnin P. Targeting of FGF-Signaling Re-Sensitizes Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST) to Imatinib In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecules. 2018;23(10):2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang HY, Li SH, Yu SC, et al. Homozygous deletion of MTAP gene as a poor prognosticator in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(22):6963–6972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babina IS, Turner NC. Advances and challenges in targeting FGFR signalling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(5):318–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarker D, Molife R, Evans TR, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of TKI258, an oral, multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(7):2075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soria JC, Massard C, Magné N, Bader T, Mansfield CD, Blay JY, et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib in advanced and/or metastatic solid cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(13):2333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Bui BN, Bouché O, Adenis A, Domont J, et al. Phase II study of oral masitinib mesilate in imatinib-naïve patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastro-intestinal stromal tumour (GIST). Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(8):1344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gozgit JM, Wong MJ, Moran L, Wardwell S, Mohemmad QK, Narasimhan NI, et al. Ponatinib (AP24534), a multitargeted pan-FGFR inhibitor with activity in multiple FGFR-amplified or mutated cancer models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(3):690–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demetri GD, Reichardt P, Kang YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib for advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib (GRID): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garner AP, Gozgit JM, Anjum R, Vodala S, Schrock A, Zhou T, et al. Ponatinib inhibits polyclonal drug-resistant KIT oncoproteins and shows therapeutic potential in heavily pretreated gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(22):5745–5755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ben-Ami E, Barysauskas CM, von Mehren M, et al. Long-term follow-up results of the multicenter phase II trial of regorafenib in patients with metastatic and/or unresectable GI stromal tumor after failure of standard tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(9):1794–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mir O, Cropet C, Toulmonde M, Cesne AL, Molimard M, Bompas E, et al. Pazopanib plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumours resistant to imatinib and sunitinib (PAZOGIST): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(5):632–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(14):1052–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganjoo KN, Villalobos VM, Kamaya A, et al. A multicenter phase II study of pazopanib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) following failure of at least imatinib and sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):236–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, et al. Erdafitinib in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee PC, Hendifar A, Osipov A, Cho M, Li D, Gong J. Targeting the Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor (FGFR) in Advanced Cholangiocarcinoma: Clinical Trial Progress and Future Considerations. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(7):1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelly CM, Shoushtari AN, Qin LX, et al. A phase Ib study of BGJ398, a pan-FGFR kinase inhibitor in combination with imatinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Invest New Drugs. 2019;37(2):282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Napolitano A, Vincenzi B. Secondary KIT mutations: the GIST of drug resistance and sensitivity. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(6):577–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Debiec-Rychter M, Cools J, Dumez H, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib mesylate in gastrointestinal stromal tumors and activity of the PKC412 inhibitor against imatinib-resistant mutants. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):270–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miselli FC, Casieri P, Negri T, et al. c-Kit/PDGFRA gene status alterations possibly related to primary imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(8):2369–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SY, Ahn T, Bang H, et al. Acquired resistance to LY2874455 in FGFR2-amplified gastric cancer through an emergence of novel FGFR2-ACSL5 fusion. Oncotarget. 2017;8(9):15014–15022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Antonescu CR, Romeo S, Zhang L, et al. Dedifferentiation in gastrointestinal stromal tumor to an anaplastic KIT-negative phenotype: a diagnostic pitfall: morphologic and molecular characterization of 8 cases occurring either de novo or after imatinib therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37(3):385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Offin M, Somwar R, Rekhtman N, et al. Acquired ALK and RET Gene Fusions as Mechanisms of Resistance to Osimertinib in EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:PO.18.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.