This randomized clinical trial evaluates the safety and efficacy of the monoclonal anti-tau antibody semorinemab in individuals with prodromal to mild Alzheimer disease.

Key Points

Question

Does treatment with the anti-tau antibody semorinemab reduce disease progression in prodromal to mild Alzheimer disease?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 457 participants with prodromal to mild Alzheimer disease, similar increases in Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes score and [18F]GTP1 tau positron emission tomography uptake were seen in the 3 semorinemab arms (1500 mg, 4500 mg, and 8100 mg) and the placebo arm throughout 18 months.

Meaning

Semorinemab treatment did not slow the rate of cerebral tau accumulation or clinical decline in prodromal to mild Alzheimer disease.

Abstract

Importance

Neurofibrillary tangles composed of aggregated tau protein are one of the neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer disease (AD) and correlate with clinical disease severity. Monoclonal antibodies targeting tau may have the potential to ameliorate AD progression by slowing or stopping the spread and/or accumulation of pathological tau.

Objective

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of the monoclonal anti-tau antibody semorinemab in prodromal to mild AD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial was conducted between October 18, 2017, and July 16, 2020, at 97 sites in North America, Europe, and Australia. Individuals aged 50 to 80 years (inclusive) with prodromal to mild AD, Mini-Mental State Examination scores between 20 and 30 (inclusive), and confirmed β-amyloid pathology (by positron emission tomography or cerebrospinal fluid) were included.

Interventions

During the 73-week blinded study period, participants received intravenous infusions of placebo or semorinemab (1500 mg, 4500 mg, or 8100 mg) every 2 weeks for the first 3 infusions and every 4 weeks thereafter.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were change from baseline on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes score from baseline to week 73 and assessments of the safety and tolerability for semorinemab compared with placebo.

Results

In the modified intent-to-treat cohort (n = 422; mean [SD] age, 69.6 [7.0] years; 235 women [55.7%]), similar increases were seen on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes score in the placebo (n = 126; Δ = 2.19 [95% CI, 1.74-2.63]) and semorinemab (1500 mg: n = 86; Δ = 2.36 [95% CI, 1.83-2.89]; 4500 mg: n = 126; Δ = 2.36 [95% CI, 1.92-2.79]; 8100 mg: n = 84; Δ = 2.41 [95% CI, 1.88-2.94]) arms. In the safety-evaluable cohort (n = 441), similar proportions of participants experienced adverse events in the placebo (130 [93.1%]) and semorinemab (1500 mg: 89 [88.8%]; 4500 mg: 132 [94.7%]; 8100 mg: 90 [92.2%]) arms.

Conclusions and Relevance

In participants with prodromal to mild AD in this randomized clinical trial, semorinemab did not slow clinical AD progression compared with placebo throughout the 73-week study period but did demonstrate an acceptable and well-tolerated safety profile. Additional studies of anti-tau antibodies may be needed to determine the clinical utility of this therapeutic approach.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03289143

Introduction

Numerous neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by intracellular aggregation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein,1 including Alzheimer disease (AD), in which pathological tau deposition primarily manifests as neurofibrillary tangles.2 Tau is an attractive therapeutic target in AD, as both neuropathological3,4 and tau positron emission tomography (PET)5,6 studies demonstrate significant correlations between cerebral tau pathology and clinical disease severity.

Tau pathology in AD accumulates in a stereotyped and hierarchical fashion,3 which has contributed to the hypothesis that pathological tau spreads from cell to cell through the extracellular matrix in a prionlike manner.7 Preclinical studies suggest that passive anti-tau immunotherapy could intercept pathologic extracellular tau species and thus slow or interrupt the spread of neurofibrillary tangles deposition.8

Semorinemab (previously known as RO7105705, MTAU9937A, or RG6100) is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody that targets the N-terminal domain of tau (amino acid residues 6-23) and was selected for development because it binds all known isoforms of full-length tau (including hyperphosphorylated and oligomerized species) and has high affinity, specificity, and manufacturability. A murine version of semorinemab reduced tau-related toxicity in cell culture and tau accumulation in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy.9 A phase 1 study of semorinemab demonstrated dose-dependent target engagement and a favorable safety profile.9 These data spurred further clinical investigations of semorinemab as a therapeutic intervention in early AD.

Methods

Overview

The Tauriel study was a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group clinical trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of semorinemab in prodromal to mild AD. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. The 73-week blinded portion of the study was conducted between October 18, 2017, and July 16, 2020, at 97 sites in North America, Europe, and Australia. The results are reported here per Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.10 This study was approved by each center’s institutional review board/ethics committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki11 and the International Conference on Harmonization E6 Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. All participants and/or their legally authorized representatives provided written informed consent.

Participants

Eligible participants were aged 50 to 80 years (inclusive), met criteria for mild cognitive impairment12 or dementia13 due to AD, and had Mini-Mental State Examination14 scores between 20 and 30 (inclusive), global scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)15 of 0.5 or 1, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)16 Delayed Memory Index scores of 85 or less, and evidence of significant cerebral amyloid pathology confirmed by either β-amyloid (Aβ) PET scan (n = 341; [18F]florbetaben, [18F]florbetapir, [18F]flutemetamol, or [18F]NAV4694 via centralized independent qualitative visual review of new or prior scans)17,18,19,20 or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ(1-42) levels (n = 116; ≤1000 pg/mL, Elecsys β-amyloid [1-42] CSF immunoassay; Roche Diagnostics). Concurrent treatment with approved symptomatic AD medications (eg, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, memantine) was permitted if dosing had been stable for 2 months or more prior to screening. Race/ethnicity data were collected by self-report in jurisdictions where collection of these data was permitted.

Study Design and Treatment

Participants were randomized in a 2:3:2:3 ratio to 1500 mg, 4500 mg, or 8100 mg of semorinemab or placebo (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). More participants were allocated to the placebo and 4500-mg semorinemab arms to increase the power of comparisons between these groups, as preliminary exposure modeling suggested sufficient binding of extracellular tau species at the 4500-mg dose. Permuted block randomization was implemented by a central IxRS vendor, with stratification by AD diagnosis (prodromal [mild cognitive impairment] vs mild [dementia]) and APOE status (presence vs absence of ε4 allele). Participants, investigators, and the sponsor were blinded to treatment allocation. The first 3 doses of study drug were administered biweekly to reach steady state concentrations by the third dose. Subsequent doses were administered every 4 weeks.

Outcome Measures

The primary efficacy outcome measure was change from baseline to week 73 on the CDR–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB),21 which assesses 6 cognitive/functional domains (memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care). Scores range from 0 to 18, with higher scores indicating greater impairment. Secondary efficacy outcome measures included change from baseline to week 73 on the 13-item version of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog-13),22 RBANS total index,16 Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADCS-ADL),23 and Amsterdam Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (A-IADL-Q).24 As the CDR and RBANS were administered at screening and before the first dose of study drug, baseline values for the CDR-SB and RBANS total index were defined as the mean score across those assessments. For other efficacy outcome measures, baseline values were derived from the last assessment prior to the first dose of study drug. Longitudinal clinical efficacy assessments were performed at weeks 25, 49, 69 (CDR only), and 73. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the CDR, ADCS-ADL, and A-IADL-Q were administered telephonically for a subset of participants as of March 2020 for assessments after week 49 (13% of week-69 CDRs, 16% of week-73 CDRs).

Blood samples were collected at multiple time points for secondary outcomes, including semorinemab serum pharmacokinetics and the presence of antidrug antibodies, and exploratory pharmacodynamic end points, including plasma total tau levels (matrix extension for Elecsys CSF tTau assay; Roche Diagnostics). CSF samples were collected from a subset of participants at screening or baseline, week 49, and week 73 to measure semorinemab concentrations and exploratory biomarker end points, including total (tTau) and hyperphosphorylated tau (pTau181) levels (Elecsys in vitro diagnostic immunoassays; Roche Diagnostics). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assays are described in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were performed at screening, week 9, week 49, and week 73, and included T1, T2*, and T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences. Volumetric and safety analyses were performed by a central MRI vendor (NeuroRx). T1 sequences were used to determine change from baseline to week 73 in ventricular, whole brain, cerebral cortex, and hippocampal volumes. A subset of participants underwent [18F]GTP1 tau PET25 at baseline, week 49, and week 73. A central PET vendor (Invicro) determined [18F]GTP1 standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) across a whole cortical gray region of interest using cerebellar gray matter as reference (without partial volume correction). Change from baseline to week 73 on this measure was calculated as an exploratory pharmacodynamic end point. Neuroimaging procedures are described in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Safety Monitoring

The primary safety outcomes were the nature, frequency, and severity of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs by treatment arm from baseline through week 73. Safety assessments included clinical laboratory testing, clinical examinations, and brain MRI (for neuroimaging abnormalities). An unblinded independent safety monitoring committee conducted quarterly reviews of all safety data.

Statistical Analyses

Assuming an observed treatment effect of 0.6 points (40% reduction in an expected 1.5-point mean increase in the placebo arm) on the CDR-SB between the 4500-mg semorinemab and placebo arms, a standard deviation of 2.0 across participants, and a 25% dropout rate, this study was expected to yield 80% power at the α = .20 level. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute) or R software version 3.6.3 (R Foundation).

Efficacy analyses were performed on a modified intent-to-treat (mITT) cohort, which included all randomized participants with primary efficacy end point (CDR-SB) data at baseline and at least 1 postbaseline time point. Mean changes from baseline at each time point were compared across treatment arms using least-squares mean estimates from mixed models for repeated measures models (adjusting for respective baseline value, age, ApoE4 status, and diagnosis), which incorporate all data collected up to and including the time point in question. Additional sensitivity analyses assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on drug exposure and/or data collection. The safety-evaluable population included all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of study drug (semorinemab or placebo).

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

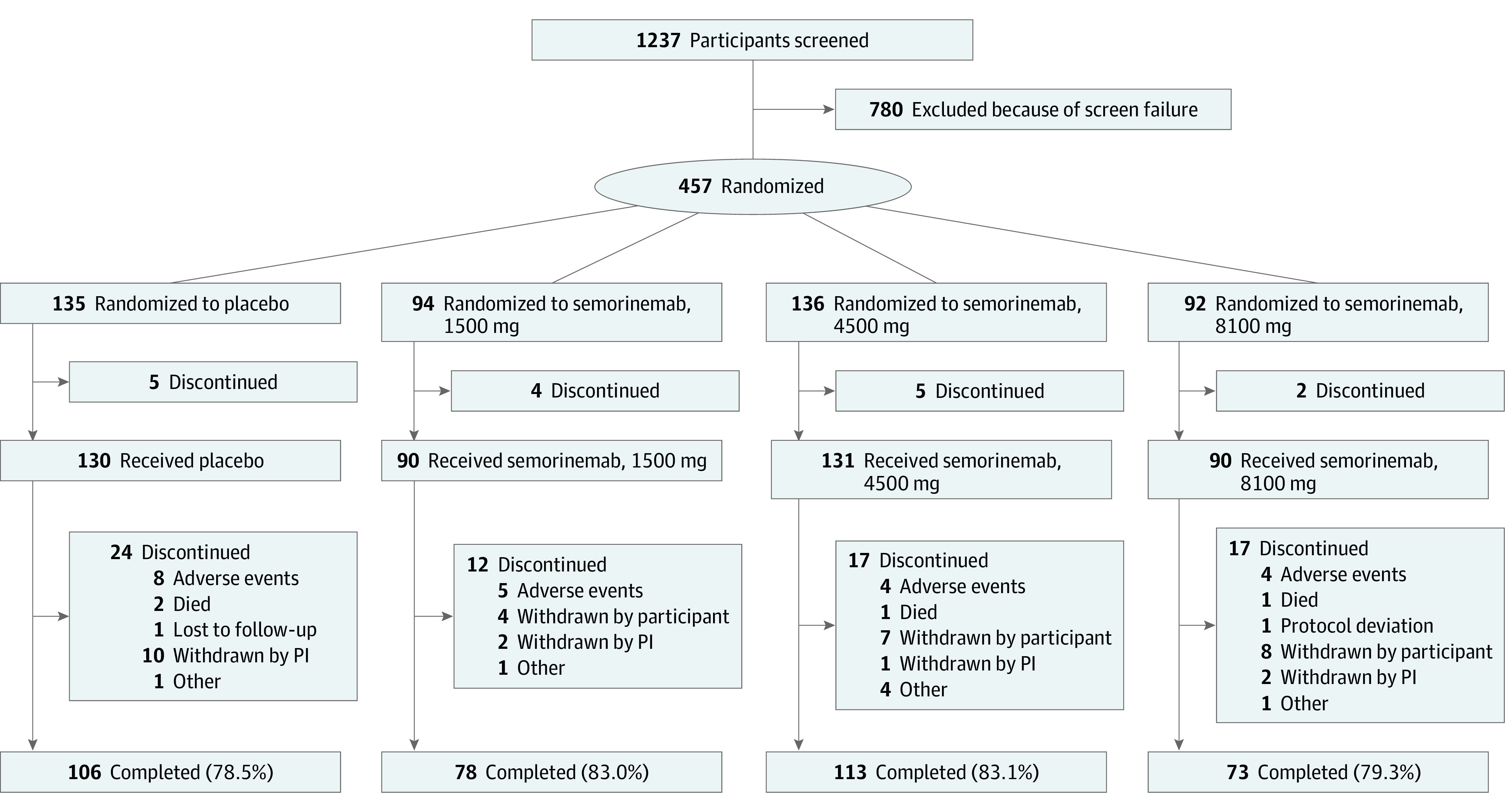

Figure 1 illustrates participant disposition; 457 were randomized, 441 received at least 1 dose of semorinemab or placebo (safety-evaluable cohort), and 422 were included in the mITT cohort. The overall discontinuation rate during the blinded portion of the study was 19% and was similar across treatment arms. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics (mITT cohort in Table 1, all participants in eTable 1 in Supplement 2, and safety-evaluable cohort in eTable 2 in Supplement 2) were balanced across treatment arms. Of 422 individuals, 388 (91.9%) were White, and other individuals were American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, multiple race and ethnicity, or unknown. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, 72 participants missed a total of 112 planned doses between March 2020 and the end of the blinded period.

Figure 1. Participant Disposition.

PI indicates principal investigator.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics for Modified Intent-to-Treat Cohort (n = 422).

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 126) | Semorinemab | |||

| 1500 mg (n = 86) | 4500 mg (n = 126) | 8100 mg (n = 84) | ||

| Age, y | 69.8 (7.3) | 70.3 (6.8) | 69.0 (7.1) | 69.4 (6.8) |

| Female, No. (%) | 71 (56.3) | 47 (54.7) | 74 (58.7) | 43 (51.2) |

| Male, No. (%) | 55 (43.7) | 39 (45.3) | 52 (41.3) | 41 (48.8) |

| Non-Hispanic White, No. (%)a | 120 (95.2) | 72 (87.3) | 113 (89.7) | 71 (84.5) |

| ≥High school, No. (%) | 102 (81.0) | 71 (82.6) | 96 (76.2) | 69 (82.1) |

| APOE4 carrier, No. (%) | 91 (72.2) | 63 (73.3) | 92 (73.0) | 63 (75.0) |

| Mild AD, No. (%) | 84 (66.7) | 57 (66.3) | 84 (66.7) | 49 (58.3) |

| Symptomatic AD therapy, No. (%)b | 90 (71.4) | 56 (65.1) | 90 (71.4) | 53 (63.1) |

| MMSE score | 23.1 (2.6) | 23.4 (2.6) | 23.5 (2.8) | 23.1 (2.7) |

| CDR-SB score | 4.0 (1.7) | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.5) | 3.8 (1.8) |

| ADAS-Cog-13 score | 28.7 (8.1) | 27.5 (7.1) | 29.0 (7.5) | 28.9 (8.0) |

| RBANS total index score | 65.5 (1.1) | 65.5 (1.2) | 64.7 (1.0) | 64.8 (1.2) |

| ADCS-ADL score | 66.9 (8.8) | 68.8 (5.9) | 68.7 (6.8) | 67.7 (7.8) |

| A-IADL-Q score | 51.4 (0.9) | 51.2 (1.0) | 50.5 (0.8) | 52.2 (1.0) |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; ADCS-ADL, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale; ADAS-Cog-13, 13-item Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale; A-IADL-Q, Amsterdam Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.

Other race and ethnic groups included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, multiple, and unknown.

Symptomatic AD therapy includes use of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and/or memantine.

Efficacy

In the mITT cohort, efficacy analyses using mixed models for repeated measures models showed no differences in rates of clinical decline between the placebo arm and any semorinemab dose arm at any post-dosing time point on the CDR-SB, ADAS-Cog-13, RBANS total index, ADCS-ADL, or A-IADL-Q (Figure 2). Sensitivity analyses exploring the effects of COVID-19–related study disruptions on the primary efficacy end point (CDR-SB) were conducted using (1) last observation carried forward imputation or excluding data, (2) from remote assessments, (3) from participants with consecutive missed doses of study drug, (4) collected after a participant’s first COVID-19–related protocol deviation, or (5) collected after March 11, 2020 (World Health Organization declaration of COVID-19 pandemic). Each analysis yielded results similar to the primary analysis (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). Planned subgroup analyses of longitudinal change on the CDR-SB stratified by baseline [18F]GTP1 tau PET SUVR in the temporal lobe (high [≥1.3] vs low [<1.3]), diagnosis (prodromal vs mild AD), age (≤65 vs >65 years), APOE status (ε4+ vs ε4−), and sex (male vs female) also failed to demonstrate consistent treatment effects attributable to semorinemab (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Mixed Models for Repeated Measures–Adjusted Change From Baseline in the Placebo and Semorinemab Treatment Arms .

Error bars represent 95% CIs. The numbers of participants in each dose arm assessed at each time point on each outcome measure are shown in the data beneath each graph. ADCS-ADL indicates Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale; ADAS-Cog-13, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale; A-IADL-Q, Amsterdam Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.

Semorinemab Pharmacokinetics in Serum and CSF

Steady-state semorinemab serum trough concentrations increased in a dose-dependent fashion (eFigure 4A in Supplement 2). Pharmacokinetic results suggested serum semorinemab concentrations were consistent with phase 1 data from healthy volunteers (median half-life of 32.3 days).9 Likewise, among participants undergoing serial lumbar punctures, semorinemab CSF trough concentrations increased in a dose-dependent fashion (eFigure 4B in Supplement 2). Similar mean (SD) CSF:serum semorinemab ratios were seen across dose arms (week 49: 1500 mg, 0.34% [0.24%]; 4500 mg, 0.33% [0.18%]; 8100 mg, 0.29% [0.15%]; week 73: 1500 mg, 0.28% [0.18%]; 4500 mg, 0.28% [0.12%]; 8100 mg, 0.22% [0.09%]), and were consistent with CSF:serum ratios observed in phase 1.9 No antidrug antibodies to semorinemab were detected.

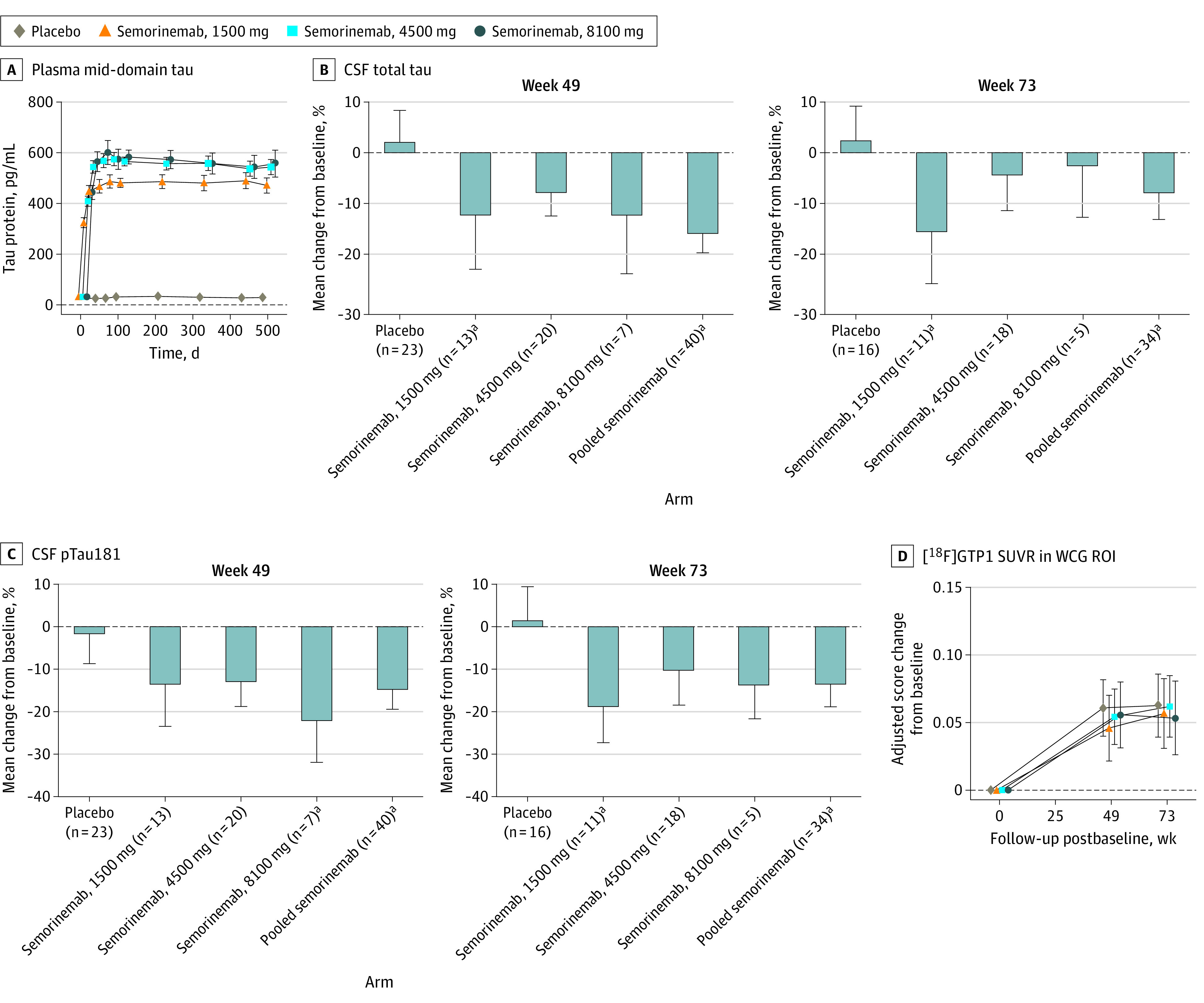

Plasma and CSF Tau Indices

Plasma total tau (Figure 3A) remained unchanged in the placebo arm but increased in a dose-dependent fashion in the 1500-mg and 4500-mg semorinemab arms and appeared to saturate above the 4500-mg dose, replicating prior findings9 and suggesting peripheral target engagement, since anti-tau antibodies increase the circulating half-life of plasma tau.26 Among participants with longitudinal CSF data, CSF tTau and pTau181 levels (Figure 3B and C; eTable 3 in Supplement 2) remained stable relative to baseline at weeks 49 and 73 in the placebo arm but showed modest, although not dose-dependent, declines across semorinemab dose arms. Analyses of variance indicated significant effects of treatment arm for change from baseline at both time points for CSF tTau (week 49: F3,59 = 3.73, P = .02; week 73: F3,46 = 2.80, P = .050) and pTau181 (week 49: F3,59 = 4.05, P = .01; week 73: F3,46 = 3.79, P = .02). Post hoc analyses for individual semorinemab arms were limited by small sample sizes, but pooled semorinemab data showed significant declines relative to placebo in CSF tTau (week 49: t61 = 3.23, P = .002; week 73: t48 = 2.19, P = .03) and pTau181 (week 49: t61 = 3.21, P = .002; week 73: t48 = 3.07, P = .004).

Figure 3. Tau Biomarkers in the Placebo and Semorinemab Treatment Arms.

Error bars represent 95% CIs. Mean absolute values for baseline, week 49, and week 73 and change from baseline at weeks 49 and 73 are shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 2. Mean absolute values for baseline, week 49, and week 73 are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 2. CSF indicates cerebrospinal fluid; pTau181, phosphorylated tau 181; ROI, region of interest; SUVR, standardized uptake value ratio; WCG, whole cortical gray.

aP < .05 vs placebo arm.

Neuroimaging Biomarkers

Volumetric MRI analyses (eFigure 5 in Supplement 2) demonstrated significant longitudinal declines in whole brain, cerebral cortex, and hippocampal volumes and concomitant increases in ventricular volume across treatment arms. There were no differences between any treatment arms in rates of cerebral atrophy on any measure. [18F]GTP1 tau PET SUVR in the whole cortical gray region of interest is plotted as change from baseline through weeks 49 and 73 in Figure 3D and listed in tabular form in eTable 4 in Supplement 2. Across treatment arms, significant increases in [18F]GTP1 SUVR were seen at both postbaseline time points, consistent with detectable increases in cerebral tau deposition during the study. There were no differences between treatment arms in the rate of increase in [18F]GTP1 SUVR. Analyses of in vivo Braak stage regions of interest27 yielded analogous results (eFigure 6 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

The overall proportions of participants experiencing AEs were balanced between treatment arms; most AEs were grade 1 or 2 in severity (Table 2). The most commonly reported AEs were fall, nasopharyngitis, and infusion-related reaction. All infusion-related reactions were grade 1 or 2 in severity and no participants discontinued the blinded portion of the study owing to any infusion-related reactions. There was an imbalance in the incidence of grade 3 or higher AEs, with more events in the semorinemab arms. However, these higher-grade AEs, which did not appear to be dose-dependent, were broadly distributed across different system organ classes, without clear imbalances within individual system organ classes. The most common higher-grade AEs were falls (placebo: 2 [1.5%]; 1500 mg: 2 [2.2%]; 4500 mg: 2 [1.5%], 8100 mg: 1 [1.1%]) and pneumonia (placebo: 1 [0.8%]; 1500 mg: 1 [1.1%]; 4500 mg: 1 [1.5%]; 8100 mg: 2 [2.2%]). Overall, 22 participants (4.8%) were discontinued owing to AEs, with a higher proportion in the placebo arm relative to semorinemab arms. An imbalance in serious AEs was observed, with higher rates in the semorinemab arms, primarily in the infections/infestations (placebo: 2 [1.5%]; 1500 mg: 3 [3.4%]; 4500 mg: 4 [3.0%]; 8100 mg: 6 [6.7%]) and psychiatric disorders (placebo: 1 [0.8%]; 1500 mg: 2 [2.2%]; 4500 mg: 4 [3.0%]; 8100 mg: 3 [3.3%]) system organ classes. The most commonly reported serious AEs are listed in eTable 5 in Supplement 2. Four deaths occurred during the blinded portion of the study (placebo: 2; 4500 mg: 1; 8100 mg: 1). None were considered related to study drug by investigators.

Table 2. Summary of Adverse Events (AEs) in Safety-Evaluable Cohort.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 130) | Semorinemab | |||

| 1500 mg (n = 89) | 4500 mg (n = 132) | 8100 mg (n = 90) | ||

| Any AE | 121 (93.1) | 79 (88.8) | 124 (93.9) | 83 (92.2) |

| Any serious AE | 14 (10.8) | 17 (19.1) | 17 (12.9) | 16 (17.8) |

| Discontinued due to AE | 8 (6.2) | 5 (5.6) | 6 (4.5) | 3 (3.3) |

| Grade ≥3 AE | 18 (13.8) | 22 (24.7) | 18 (13.6) | 16 (17.8) |

| Deaths | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) |

| AEs reported in ≥5% | ||||

| Fall | 23 (17.7) | 14 (15.7) | 23 (17.4) | 8 (8.9) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 11 (8.5) | 5 (5.6) | 18 (13.6) | 12 (13.3) |

| Infusion-related reaction | 6 (4.6) | 10 (11.2) | 11 (8.3) | 6 (6.7) |

| Arthralgia | 8 (6.2) | 6 (6.7) | 10 (7.6) | 8 (8.9) |

| Hypertension | 7 (5.4) | 4 (4.5) | 14 (10.6) | 5 (5.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 10 (7.7) | 5 (5.6) | 10 (7.6) | 6 (6.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 15 (11.5) | 6 (6.7) | 7 (5.3) | 5 (5.6) |

| Back pain | 8 (6.2) | 5 (5.6) | 9 (6.8) | 6 (6.7) |

| Dizziness | 12 (9.3) | 5 (5.6) | 6 (4.5) | 7 (7.8) |

| Anxiety | 3 (2.3) | 10 (11.2) | 6 (4.6) | 6 (6.7) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (3.1) | 5 (5.6) | 10 (7.6) | 4 (4.4) |

| Headache | 10 (7.7) | 2 (2.3) | 8 (6.1) | 6 (6.7) |

| Nausea | 0 (0) | 9 (10.1) | 8 (6.1) | 4 (4.4) |

| Cough | 4 (3.1) | 6 (6.7) | 7 (5.3) | 5 (5.6) |

| Depression | 5 (3.8) | 5 (5.6) | 7 (5.3) | 5 (5.6) |

| Agitation | 2 (1.5) | 5 (5.6) | 6 (4.5) | 4 (4.4) |

| Insomnia | 3 (2.3) | 2 (2.2) | 4 (3.0) | 5 (5.6) |

| Blood pressure increased | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (6.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| Fatigue | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (3.0) | 5 (5.6) |

| Skin laceration | 4 (3.1) | 6 (6.7) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

MRI Abnormalities

The postbaseline incidence of new MRI abnormalities (vasogenic edema/sulcal effusion, superficial siderosis, microhemorrhage, and microhemorrhage) were balanced across treatment arms (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Two participants (1 each in placebo and 4500-mg semorinemab arms) had asymptomatic sulcal effusions, which resolved spontaneously after study medication was held. Overall, the incidence of new MRI abnormalities was consistent with previous reports.28,29,30,31

Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study in prodromal to mild AD, no differences were seen between the placebo arm and any semorinemab dose arm on the primary efficacy end point (CDR-SB), secondary efficacy end points (ADAS-Cog-13, RBANS total index, ADCS-ADL, and A-IADL-Q), or [18F]GTP1 tau PET. Furthermore, despite exploration of a wide dose range for semorinemab (1500 mg to 8100 mg), there was no consistent evidence for dose-dependent effects across end points and/or time points. Semorinemab demonstrated an acceptable and well-tolerated safety profile. Together, these data indicate that semorinemab failed to demonstrate meaningful efficacy on clinical end points or reduction of tau accumulation across 18 months in participants with prodromal to mild AD at the doses administered.

The participant population demonstrated significant decline on the CDR-SB and each secondary end point in all treatment arms. Rates of decline on the CDR-SB were comparable with those reported from placebo arms of other AD studies with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria.32 Likewise, significant accumulation of additional tau pathology was observed with [18F]GTP1 tau PET imaging, with longitudinal increases in whole cortical gray SUVR signal comparable with those reported in prior observational tau PET studies of similar cohorts.33,34 Taken together, these data suggest that the failure to detect treatment effects with semorinemab was not attributable to insufficient disease progression.

Serum and CSF pharmacokinetic data were consistent with prior phase 1 findings,9 demonstrating dose-dependent increases in both compartments. The CSF:serum ratios observed in this study are comparable with those reported for other anti-Aβ35,36 and anti-tau37,38 antibodies in clinical development. Semorinemab appeared to modulate CSF tau levels across the wide range of doses administered, but in the absence of dose-dependent effects on clinical, tau PET, and CSF tau indices, it remains unclear what central nervous system levels of monoclonal anti-tau antibodies might be needed to meaningfully interrupt the spread of pathological tau. Nevertheless, the highest dose of semorinemab tested in this study (8100 mg every 4 weeks) is near the practical limit for clinical use given current commercial antibody production capacities.

It remains uncertain why the preclinical efficacy of the murine surrogate of semorinemab for reducing tau accumulation9 was not replicated in the Tauriel study. One possibility is that the N-terminal tau epitope recognized by semorinemab is not present in the tau species that are primarily responsible for tau spread in prodromal to mild AD. Our preclinical studies used the P301L transgenic mouse model,9 which incorporates a familial frontotemporal dementia variation that overexpresses 4R tau (as opposed the mixed 3R/4R tau seen in AD). Prior work in cell culture and in vivo tau spreading models that use tau isolated from postmortem human AD brain suggests that antibodies targeting epitopes in other regions of the tau protein may be more effective than N-terminal targeted antibodies in reducing tau seeding and/or spreading.39,40,41 However, pathogenic tau spreading species may differ between individual patients with AD, and the optimal tau epitope to target may be patient specific42 and/or disease stage specific because tau pathology evolves with disease progression.43,44 Alternatively, the predominant mechanism for cell-to-cell tau spread may differ between preclinical models and patients with AD. In particular, the therapeutic hypothesis underlying anti-tau monoclonal antibody approaches presumes that free tau in the extracellular space (approximately 90% in rodent models45) is the primary spreading species. However, tau may also spread from cell to cell in patients with AD via other membrane-enclosed mechanisms, including exosomes, endosomes, and nanotubes,8 which would preclude antibody clearance. It has also been postulated that the cell-to-cell tau spread seen in preclinical models, regardless of the underlying route, may not drive tau-related neurodegeneration.46 Given the continued accumulation of tau pathology (as measured by tau PET) in the semorinemab dose arms, our results do not directly address the validity of the tau-spreading hypothesis of AD pathogenesis.7

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to missed doses and/or remote or missed clinical assessments for some participants. Targeted sensitivity analyses yielded results similar to the overall analyses, but more subtle pandemic-related effects may have been obscured. Relatively few longitudinal CSF samples were available for analyses of tau indices, limiting the ability to determine whether semorinemab-related reductions in CSF tau were dose-dependent and/or related to clinical outcomes. The limited racial and ethnic diversity among trial participants may restrict the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

These negative results represent the first published report, to our knowledge, of phase 2 clinical data of an anti-tau monoclonal antibody in prodromal to mild AD, although similarly negative results of other N-terminal anti-tau antibodies (gosuranemab, tilavonemab) in analogous patient populations have recently been announced.47,48 Nevertheless, while the specific role of tau in AD pathogenesis remains uncertain, it remains a compelling therapeutic target.46 Additional studies of monoclonal anti-tau antibodies that target other tau epitopes and/or different stages of AD will help determine whether this mechanistic approach remains viable or whether other anti-tau strategies should be prioritized for future clinical drug development.

Trial protocol.

eMethods

eTable 1. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for all randomized participants per treatment assignment

eTable 2. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for safety-evaluable cohort per treatment received (n=441)

eTable 3. Mean absolute values for CSF tau indices

eTable 4. Mean absolute values for [18F]GTP1 SUVRs in the whole cortical gray ROI

eTable 5. Summary of most commonly reported serious adverse events (≥ 2 participants in any individual treatment arm)

eTable 6. Incidence of selected MRI findings

eFigure 1. Tauriel study schema

eFigure 2. Sensitivity analyses exploring the effects of COVID-19 related study disruption in the placebo and semorinemab (semo) treatment arms on the CDR-SB

eFigure 3. Planned subgroup analyses of change from baseline to Week 73 in the placebo and semorinemab (semo) treatment arms on CDR-SB

eFigure 4. Semorinemab (semo) trough concentrations

eFigure 5. Change in MRI volume from baseline in the placebo and semorinemab treatment arms

eFigure 6. [18F]GTP1 SUVR change from baseline in Braak stage ROIs in the placebo and semorinemab (semo) treatment arms

eReferences

Nonauthor collaborators. The Tauriel Investigators

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(6):609-622. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70090-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long JM, Holtzman DM. Alzheimer disease: an update on pathobiology and treatment strategies. Cell. 2019;179(2):312-339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(3):271-278. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71(5):362-381. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD Sr, Navitsky M, et al. ; 18F-AV-1451-A05 investigators . Relationships between flortaucipir PET tau binding and amyloid burden, clinical diagnosis, age and cognition. Brain. 2017;140(3):748-763. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng E, Ward M, Manser PT, et al. Cross-sectional associations between [18F]GTP1 tau PET and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;81:138-145. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons GS, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Mechanisms of cell-to-cell transmission of pathological tau: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(1):101-108. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colin M, Dujardin S, Schraen-Maschke S, et al. From the prion-like propagation hypothesis to therapeutic strategies of anti-tau immunotherapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;139(1):3-25. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02087-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayalon G, Lee SH, Adolfsson O, et al. Antibody semorinemab reduces tau pathology in a transgenic mouse model and engages tau in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(593):eabb2639. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abb2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726-732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412-2414. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):310-319. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piramal Imaging . Neuraceq (florbetaben F 18 injection) [package insert]. Updated March 2014. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/204677s000lbl.pdf

- 18.Eli Lilly and Co . Amyvid (florbetapir F 18 injection) [package insert]. Updated April 2012. Accessed December 29, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202008s000lbl.pdf

- 19.Healthcare GE. Vizamyl (flutemetamol F 18 injection) [package insert]. Updated April 2016. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/203137s005lbl.pdf

- 20.Ng KP, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, selegiline, reduces 18F-THK5351 uptake in the human brain. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0253-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg L, Miller JP, Storandt M, et al. Mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type: 2: longitudinal assessment. Ann Neurol. 1988;23(5):477-484. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohs RC, Knopman D, Petersen RC, et al. Development of cognitive instruments for use in clinical trials of antidementia drugs: additions to the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale that broaden its scope: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(suppl 2):S13-S21. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(suppl 2):S33-S39. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, et al. A new informant-based questionnaire for instrumental activities of daily living in dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(6):536-543. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanabria Bohórquez S, Marik J, Ogasawara A, et al. [18F]GTP1 (Genentech Tau Probe 1), a radioligand for detecting neurofibrillary tangle tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(10):2077-2089. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04399-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanamandra K, Patel TK, Jiang H, et al. Anti-tau antibody administration increases plasma tau in transgenic mice and patients with tauopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(386):eaal2029. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schöll M, Lockhart SN, Schonhaut DR, et al. PET imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron. 2016;89(5):971-982. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goos JD, Henneman WJ, Sluimer JD, et al. Incidence of cerebral microbleeds: a longitudinal study in a memory clinic population. Neurology. 2010;74(24):1954-1960. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e396ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostrowitzki S, Lasser RA, Dorflinger E, et al. ; SCarlet RoAD Investigators . A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0318-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson C, Siemers E, Hake A, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities from trials of solanezumab for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2016;2:75-85. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ketter N, Brashear HR, Bogert J, et al. Central review of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in two phase III clinical trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(2):557-573. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teng E, Manser P, Hu N, et al. Comparison of the FCSRT and RBANS in screening for early AD clinical trials: Enrichment for disease progression. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(4):S27-S28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Schwarz CG, et al. Longitudinal tau PET in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2018;141(5):1517-1528. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pontecorvo MJ, Devous MD, Kennedy I, et al. A multicentre longitudinal study of flortaucipir (18F) in normal ageing, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Brain. 2019;142(6):1723-1735. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logovinsky V, Satlin A, Lai R, et al. Safety and tolerability of BAN2401: a clinical study in Alzheimer’s disease with a protofibril selective Aβ antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0181-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida K, Moein A, Bittner T, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effect of crenezumab on plasma and cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-0580-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West T, Hu Y, Verghese PB, et al. Preclinical and clinical development of ABBV-8E12, a humanized anti-tau antibody, for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4(4):236-241. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2017.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boxer AL, Qureshi I, Ahlijanian M, et al. Safety of the tau-directed monoclonal antibody BIIB092 in progressive supranuclear palsy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending dose phase 1b trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(6):549-558. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30139-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandermeeren M, Borgers M, Van Kolen K, et al. Anti-tau monoclonal antibodies derived from soluble and filamentous tau show diverse functional properties in vitro and in vivo. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;65(1):265-281. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albert M, Mairet-Coello G, Danis C, et al. Prevention of tau seeding and propagation by immunotherapy with a central tau epitope antibody. Brain. 2019;142(6):1736-1750. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Courade JP, Angers R, Mairet-Coello G, et al. Epitope determines efficacy of therapeutic anti-tau antibodies in a functional assay with human Alzheimer tau. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(5):729-745. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1911-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dujardin S, Commins C, Lathuiliere A, et al. Tau molecular diversity contributes to clinical heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1256-1263. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0938-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wesseling H, Mair W, Kumar M, et al. Tau PTM profiles identify patient heterogeneity and stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2020;183(6):1699-1713.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moloney CM, Lowe VJ, Murray ME. Visualization of neurofibrillary tangle maturity in Alzheimer’s disease: a clinicopathologic perspective for biomarker research. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(9):1554-1574. doi: 10.1002/alz.12321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dujardin S, Bégard S, Caillierez R, et al. Ectosomes: a new mechanism for non-exosomal secretion of tau protein. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang CW, Shao E, Mucke L. Tau: Enabler of diverse brain disorders and target of rapidly evolving therapeutic strategies. Science. 2021;371(6532):eabb8255. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shulman M, Rajagovindan R, Kong J, et al. Top-line results from TANGO, a Phase 2 study of gosuranemab in participants with mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease and mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(4):S65-S66. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Florian H, Wang D, Guo Q, Jin Z, Fisseha N, Rendenbach-Mueller B. Phase 2 study of tilavonemab, an anti-tau antibody, in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(4):S50-S51. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol.

eMethods

eTable 1. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for all randomized participants per treatment assignment

eTable 2. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for safety-evaluable cohort per treatment received (n=441)

eTable 3. Mean absolute values for CSF tau indices

eTable 4. Mean absolute values for [18F]GTP1 SUVRs in the whole cortical gray ROI

eTable 5. Summary of most commonly reported serious adverse events (≥ 2 participants in any individual treatment arm)

eTable 6. Incidence of selected MRI findings

eFigure 1. Tauriel study schema

eFigure 2. Sensitivity analyses exploring the effects of COVID-19 related study disruption in the placebo and semorinemab (semo) treatment arms on the CDR-SB

eFigure 3. Planned subgroup analyses of change from baseline to Week 73 in the placebo and semorinemab (semo) treatment arms on CDR-SB

eFigure 4. Semorinemab (semo) trough concentrations

eFigure 5. Change in MRI volume from baseline in the placebo and semorinemab treatment arms

eFigure 6. [18F]GTP1 SUVR change from baseline in Braak stage ROIs in the placebo and semorinemab (semo) treatment arms

eReferences

Nonauthor collaborators. The Tauriel Investigators

Data Sharing Statement