Abstract

Multi-locus sequence analysis (MLSA) has been proved to be a useful method for Streptomyces identification and MLSA distance of 0.007 is considered as the boundary value. However, we found that MLSA distance of 0.007 might be insufficient to act as a threshold according to the correlations among average nucleotide identity based on MuMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool (ANIm), digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) and MLSA from the 80 pairs of Streptomyces species; in addition, a 70% dDDH value did not correspond to a 95∼96% ANIm value but approximately to 96.7% in the genus Streptomyces. Based on our analysis, it was proposed that when the MLSA distance value between a novel Streptomyces and a reference strain was < 0.008, the novel strain could be considered as a heterotypic synonym of the reference strain; when the MLSA distance value was ≥ 0.014, the novel strain could be regarded as a new Streptomyces species; when the MLSA distance value was between 0.008 and 0.014 (not included), the dDDH or ANIm value between a new strain and a reference strain must be calculated in order to determine the taxonomic status of a novel strain. In this context, a 70% dDDH or 96.7% ANIm value could act as the threshold value in delineating Streptomyces species, but if the dDDH or ANIm value was less than but close to 70 or 96.7% cut-off point, the taxonomic status of a novel strain could only be determined by a combination of phenotypic characteristics, chemotaxonomic characteristics and phylogenomic analysis.

Keywords: new insights, ANIm, dDDH, MLSA, Streptomyces

Introduction

In current prokaryote systematics, the classification of Bacteria and Archaea is based on a polyphasic taxonomic approach, comprised of phenotypic, chemotaxonomic and genotypic data, as well as phylogenetic information (Schleifer, 2009). Of these, the classical DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) technology plays a key role in novel species identification. Although DDH has been the “gold standard” for bacterial species demarcation over the last 50 years, its procedures are known to be labor-intensive, error-prone and do not allow the generation of cumulative databases. Thus, there has been an urgent need for an alternative genotype-based standard (Stackebrandt et al., 2002; Gevers et al., 2005). With the rapid progress in the area of genome sequencing technology, many efforts have been made to develop a bioinformatic method to replace classical DDH for differentiating species. These efforts were mainly focused on devising values analogous to DDH values, such as genome BLAST distance phylogeny (GBDP) (Henz et al., 2005), average nucleotide identity (ANI) (Konstantinidis et al., 2006), maximal unique matches index (MUMi) (Deloger et al., 2009) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) (Auch et al., 2010). At present, ANI or dDDH has been most widely used as a gold standard for species delineation. Unfortunately, over the last two decades, even though a lot of efforts have been made to obtain genome data for prokaryotic organism, only approximately 2.1% of the global prokaryotic taxa are represented by sequenced genomes (Zhang et al., 2020). As far as Streptomyces species are concerned, genome data of about 30% type species with validly published and correct names are still unavailable at the time of writing this article1. In contrast, the nearly entire database of 16S rRNA gene sequences is available for the type strains of the genus Streptomyces. Nevertheless, when sequence similarity of 16S rRNA gene between two strains is over 97% (Stackebrandt et al., 2002; Tindall et al., 2010), it is hard to differentiate two species using 16S rRNA gene sequences alone. Therefore, in the modern classification of Streptomyces, 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity, ANI and dDDH values are usually used in combination to assess phylogenetic position of a novel species, and only species exhibiting ≥ 98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity are required to calculate ANI or dDDH values (Konstantinidis and Tiedje, 2005; Stackebrandt and Ebers, 2006; Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013). If genome sequence data of the type strains with ≥ 98.7% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity are unavailable, it is recommended to obtain their genome sequences, not only to measure ANI and dDDH but also to extend and improve the public genome database for taxonomic purposes (Chun et al., 2018). However, even though the whole-genome sequencing is accessible to most of the microbial taxonomists at the present, it is still time-consuming and costly. Thus, it is of great significance for many microbial taxonomists to find out an alternative to ANI or dDDH. In contrast to ANI or dDDH, multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) based on housekeeping genes is a simple and low-cost approach and has been proved to be a useful method for identification of Streptomyces species (Guo et al., 2008; Rong et al., 2009, 2010; Rong and Huang, 2010, 2012; Labeda et al., 2017). In an early comparative study between DDH and MLSA, Rong and Huang proposed that the MLSA evolutionary distance of 0.007 could act as the threshold value in delineating Streptomyces species (Rong et al., 2010). However, our recent findings are somewhat different from their conclusion. In addition, we also found that the 70% dDDH value was not equivalent to the 95∼96% ANI value in the genus Streptomyces. In the present work, new insights into the threshold values of MLSA, ANI and dDDH in delineating Streptomyces species were provided based on the correlation among ANI, dDDH and MLSA from 80 pairs of Streptomyces species (including heterotypic synonyms).

Materials and Methods

Source of Genome Data and Type Strains

A total number of 95 genomes from type Streptomyces species with validly published names were downloaded from the GenBank database. The complete genome list is shown in Supplementary Table 1. All anomalous assemblies were discarded. The type strains S. albidoflavus CGMCC 4.1291T, S. canarius CGMCC 4.1581T, S. castelarensis CGMCC 4.3570T, S. chartreusis CGMCC 4.1639T, S. corchorusii CGMCC 4.1592T, S. melanosporofaciens CGMCC 4.1742T, S. mirabilis CGMCC 4.1988T, and S. olivochromogenes CGMCC 4.2000T were purchased from China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre (CGMCC), while S. koyangensis JCM 14915T and S. osmaniensis JCM 17656T were from Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM).

Correlation Among ANIm, dDDH and MLSA

Given that ANIm (average nucleotide identity based on MuMmer ultra-rapid aligning tool) provides more credible results when the pair of genomes compared share a high degree of similarity (ANI > 90%) (Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009), the ANIm value rather than the ANIb (ANI based on the BLAST algorithm) value was selected for comparative analysis in the current work. The calculations of ANIm and dDDH values were performed by using the JSpeciesWS online service (Richter et al., 2015) and the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013), respectively. For calculating dDDH value, Formula 2 was used. The sequences of five protein-coding genes (atpD, gyrB, recA, rpoB, and trpB) were directly drawn from draft genome sequences. After trimmed manually using methods of Rong and Huang (2012), five gene sequences were concatenated head-to-tail in-frame in the order of atpD, gyrB, recA, rpoB, and trpB. The MLSA evolutionary distances between a set of type strains were calculated according to Kimura’s two-parameter model (Kimura, 1980). The datasets for coherence analysis among ANIm, dDDH and MLSA were processed by Origin Pro 9.0. Coefficients of determination (R2) among ANIm, dDDH and MLSA were calculated by exponential regression analysis.

Phenotypic Characterization

The cultural characteristics of ten tested strains, i.e., S. albidoflavus CGMCC 4.1291T, S. canarius CGMCC 4.1581T, S. castelarensis CGMCC 4.3570T, S. chartreusis CGMCC 4.1639T, S. corchorusii CGMCC 4.1592T, S. koyangensis JCM 14915T, S. melanosporofaciens CGMCC 4.1742T, S. mirabilis CGMCC 4.7010T, S. olivochromogenes CGMCC 4.2000T, and S. osmaniensis JCM 17656T, were evaluated on ISP serial agar media (Shirling and Gottlieb, 1966) following incubation at 28°C for 14 days. The colors of colonies and soluble pigments were determined according to the Color Standards and Color Nomenclature (Ridgway, 1912). A range of physiological and biochemical tests were carried out according to Li et al.’s methods Li et al. (2020). Tolerance to different temperatures (4, 10, 15, 20, 25, 28, 30, 37, 40, and 45°C) was tested on ISP2 agar for 14 days. Enzyme-activity tests were carried out using API-ZYM test system (France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Other physiological characteristics including starch hydrolysis, gelatin liquefaction, milk coagulation and peptization, melanin production, Tweens (20, 40, 60, and 80) degradation, H2S production and nitrate reduction were performed according to the methods described by Xu et al. (2007). All these experiments were carried out in triplicate, and all these strains were grown under the same conditions for parallel comparison.

Chemotaxonomic Characterization

Cells were collected for chemotaxonomic analysis by centrifugation from five strains cultured at 28°C in TSB medium for 7 days on a rotary shaker and then washed twice with distilled water. The diaminopimelic acid (DAP) isomer and whole-cell sugar compositions were analyzed using TLC according to the procedures described by Lechevalier and Lechevalier (1970) and Hasegawa et al. (1983). Cellular fatty acids analysis was carried out by China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (CICC) according to the protocol of the Sherlock Microbial Identification system [MIDI system, version 6.0B, MIDI (2005)]. Menaquinones were extracted according to Collins et al. (1977) and analyzed by HPLC (Wu et al., 1989). The polar lipids were extracted and identified by the method of Kates (1986).

Phylogenomic Analysis

The genome sequences of five pairs of Streptomyces and relevant reference strains for phylogenomic analysis were retrieved from NCBI database. Phylogenomic analysis was carried out using the Type (Strain) Genome Server (Meier-Kolthoff and Göker, 2019). A phylogenetic tree was inferred with FastME (Lefort et al., 2015) from the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) distances calculated from genome sequences.

Results and Discussion

There is no doubt that MLSA plays an extremely important role in identifying Streptomyces species (Labeda et al., 2017). However, recently, during identifying a novel strain of endophytic Streptomyces from a medicinal plant, we found that the MLSA evolutionary distance between S. stelliscabiei DSM 41803T and S. bottropensis ATCC 25435T was 0.011 (greater than the 0.007 critical point proposed for delineating Streptomyces species), suggesting that they should belong to different genomic species (Rong and Huang, 2012). This result was contradictory to Madhaiyan et al.’s (2020) conclusion that S. stelliscabiei is a later heterotypic synonym of S. bottropensis based on comparative genomic analysis. Is this case an exceptional one? To answer this question, firstly, we calculated ANIm values among the majority of validly published Streptomyces species whose genomes are available. Then, all strain pairs, whose ANIm values are greater than or equal to 90%, were collected for subsequent analysis. Finally, MLSA, dDDH and ANIm values of a total of 80 pairs of Streptomyces species were randomly selected from the above strain pairs to compare with each other (Table 1). Results indicated that besides S. stelliscabiei DSM 41803T and S. bottropensis ATCC 25435T, there were six strain pairs, i.e., S. antimycoticus NBRC 12839T and S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T, S. canarius JCM 4733T and S. olivaceoviridis JCM 4499T, S. durhamensis NRRL B-3309T and S. filipinensis JCM 4369T, S. glebosus NBRC 13786T and S. platensis DSM 40041T, S. griseorubens JCM 4383T and S. matensis JCM 4277T, and S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T and S. sporoclivatus NBRC 100767T, in which not only the MLSA evolutionary distance in each pair was higher than 0.007, but also the dDDH and ANIm values were more than the 70% or 95∼96% cut-off points recommended for delineating species (Stackebrandt and Goebel, 1994; Richter and Rosselló-Móra, 2009), respectively. In addition, there were four strain pairs, i.e., S. canarius JCM 4733T and S. corchorusii DSM 40340T, S. castelarensis NRRL B-24289T and S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T, S. chartreusis ATCC 14922T and S. osmaniensis OU-63T, and S. mirabilis JCM 4551T and S. olivochromogenes DSM 40451T, in which the MLSA evolutionary distances in each pair were greater than or equal to 0.007, and the dDDH values were lower than 70%, but the ANIm values were over 95∼96%. All these data indicated that the MLSA evolutionary distance of 0.007 might be insufficient to act as the threshold value in delineating Streptomyces species.

TABLE 1.

ANIm, MLSA, and dDDH values among 78 pairs of type Streptomyces species including heterotypic synonyms.

| No. | Species 1 | Species 2 | ANIm | MLSA | dDDH |

| 1 | S. flavovariabilis NRRL B-16367T | S. variegatus NRRL B-16380T | 99.99 | 0.000 | 99.8 |

| 2 | S. almquistii NRRL B-1685T | S. albus NRRL B-1811T | 99.95 | 0.000 | 99.7 |

| 3 | S. phaeogriseichromatogenes DSM 40710T | S. griseofuscus NRRL B-5429T | 99.48 | 0.001 | 95.3 |

| 4 | S. asterosporus DSM 41452T | S. aureorectus DSM 41692T | 99.19 | 0.002 | 92.8 |

| 5 | S. aureorectus DSM 41692T | S. calvus CECT 3271T | 99.20 | 0.002 | 92.8 |

| 6 | S. asterosporus DSM 41452T | S. calvus CECT 3271T | 99.16 | 0.001 | 92.9 |

| 7 | S. plicatus JCM 4504T | S. vinaceusdrappus JCM 4529T | 99.23 | 0.002 | 93.6 |

| 8 | S. plicatus JCM 4504T | S. geysiriensis JCM 4962T | 98.97 | 0.001 | 91.2 |

| 9 | S. geysiriensis JCM 4962T | S. vinaceusdrappus JCM 4529T | 99.01 | 0.002 | 91.4 |

| 10 | S. hygroscopicus subsp. hygroscopicus NBRC 13472T | S. endus NBRC 12859T | 98.94 | 0.000 | 90.1 |

| 11 | S. puniceus NRRL ISP-5083T | S. floridae NRRL 2423T | 98.83 | 0.002 | 89.8 |

| 12 | S. sporoclivatus NBRC 100767T | S. antimycoticus NBRC 12839T | 98.75 | 0.003 | 88.6 |

| 13 | S. puniceus NRRL ISP-5083T | S. californicus NRRL B-2098T | 98.63 | 0.001 | 87.6 |

| 14 | S. californicus NRRL B-2098T | S. floridae NRRL 2423T | 98.62 | 0.002 | 87.5 |

| 15 | S. griseorubens JCM 4383T | S. matensis JCM 4277T | 97.95 | 0.008 | 80.9 |

| 16 | S. galilaeus ATCC 14969T | S. bobili NRRL B-1338T | 97.74 | 0.004 | 79.6 |

| 17 | S. glebosus NBRC 13786T | S. platensis DSM 40041T | 97.78 | 0.008 | 79.4 |

| 18 | S. castelarensis NRRL B-24289T | S. sporoclivatus NBRC 100767T | 97.49 | 0.006 | 76.2 |

| 19 | S. castelarensis NRRL B-24289T | S. antimycoticus NBRC 12839T | 97.47 | 0.005 | 75.8 |

| 20 | S. olivaceoviridis JCM 4499T | S. canarius JCM 4733T | 97.41 | 0.009 | 76.0 |

| 21 | S. griseofuscus NRRL B-5429T | S. murinus NRRL B-2286T | 97.15 | 0.004 | 74.5 |

| 22 | S. phaeogriseichromatogenes DSM 40710T | S. murinus NRRL B-2286T | 97.14 | 0.006 | 74.7 |

| 23 | S. costaricanus DSM 41827T | S. murinus NRRL B-2286T | 97.08 | 0.005 | 73.9 |

| 24 | S. filipinensis JCM 4369T | S. durhamensis NRRL B-3309T | 96.97 | 0.010 | 72.9 |

| 25 | S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T | S. sporoclivatus NBRC 100767T | 96.91 | 0.012 | 72.2 |

| 26 | S. antimycoticus NBRC 12839T | S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T | 96.90 | 0.010 | 72.0 |

| 27 | S. olivaceoviridis JCM 4499T | S. corchorusii DSM 40340T | 96.88 | 0.006 | 71.4 |

| 28 | S. recifensis NRRL B-3811T | S. griseoluteus JCM 4765T | 96.86 | 0.005 | 72.4 |

| 29 | S. stelliscabiei DSM 41803T | S. bottropensis ATCC 25435T | 96.86 | 0.011 | 70.9 |

| 30 | S. costaricanus DSM 41827T | S. griseofuscus NRRL B-5429T | 96.74 | 0.004 | 70.9 |

| 31 | S. costaricanus DSM 41827T | S. phaeogriseichromatogenes DSM 40710T | 96.73 | 0.003 | 70.9 |

| 32 | S. canarius JCM 4733T | S. corchorusii DSM 40340T | 96.69 | 0.007 | 69.5 |

| 33 | S. castelarensis NRRL B-24289T | S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T | 96.57 | 0.009 | 68.7 |

| 34 | S. chartreusis ATCC 14922T | S. osmaniensis OU-63T | 96.40 | 0.008 | 68.8 |

| 35 | S. mirabilis JCM 4551T | S. olivochromogenes DSM 40451T | 96.23 | 0.011 | 67.0 |

| 36 | S. albidoflavus NRRL B-1271T | S. koyangensis VK-A60T | 95.90 | 0.009 | 64.7 |

| 37 | S. longwoodensis DSM 41677T | S. lasalocidi X-537T | 95.47 | 0.008 | 61.8 |

| 38 | S. bauhiniae Bv016T | S. griseoluteus JCM 4765T | 95.27 | 0.014 | 60.6 |

| 39 | S. rhizosphaericola 1AS2cT | S. cavourensis DSM 41795T | 95.21 | 0.012 | 59.8 |

| 40 | S. recifensis NRRL B-3811T | S. bauhiniae Bv016T | 95.21 | 0.015 | 60.7 |

| 41 | S. xiaopingdaonensis L180T | S. sulphureus DSM 40104T | 95.20 | 0.019 | 59.7 |

| 42 | S. bauhiniae Bv016T | S. seoulensis KCTC 9819T | 95.18 | 0.013 | 60.2 |

| 43 | S. aquilus GGCR-6T | S. antibioticus DSM 40234T | 94.86 | 0.017 | 58.4 |

| 44 | S. achromogenes subsp. achromogenes NRRL B-2120T | S. achromogenes subsp. rubradiris JCM 4955T | 94.75 | 0.016 | 56.2 |

| 45 | S. parvus NRRL B-1455T | S. mediolani NRRL WC-3934T | 94.53 | 0.029 | 56.1 |

| 46 | S. recifensis NRRL B-3811T | S. seoulensis KCTC 9819T | 94.47 | 0.019 | 56.6 |

| 47 | S. galbus JCM 4639T | S. lasalocidi X-537T | 94.44 | 0.009 | 55.4 |

| 48 | S. seoulensis KCTC 9819T | S. griseoluteus JCM 4765T | 94.39 | 0.019 | 55.8 |

| 49 | S. longwoodensis DSM 41677T | S. galbus JCM 4639T | 94.33 | 0.010 | 55.0 |

| 50 | S. ochraceiscleroticus NRRL ISP-5594T | S. violens NRRL ISP-5597T | 94.24 | 0.014 | 54.5 |

| 51 | S. reniochalinae LHW50302T | S. diacarni LHW51701T | 93.51 | 0.018 | 50.2 |

| 52 | S. phaeoluteigriseus DSM 41896T | S. bobili NRRL B-1338T | 93.47 | 0.021 | 50.7 |

| 53 | S. violaceusniger NBRC 13459T | S. antioxidans MUSC 164T | 93.34 | 0.027 | 48.1 |

| 54 | S. sedi JCM 16909T | S. zhaozhouensis CGMCC 4.7095T | 93.21 | 0.021 | 48.7 |

| 55 | S. qaidamensis S10T | S. variegatus NRRL B-16380T | 93.10 | 0.037 | 49.0 |

| 56 | S. tirandamycinicus HNM0039T | S. spongiicola HNM0071T | 92.95 | 0.020 | 45.1 |

| 57 | S. flavovariabilis NRRL B-16367T | S. iakyrus NRRL ISP-5482T | 92.86 | 0.033 | 47.9 |

| 58 | S. violaceorubidus NRRL B-16381T | S. rubrogriseus NBRC 15455T | 92.80 | 0.019 | 47.3 |

| 59 | S. hawaiiensis ATCC 12236T | S. tuirus JCM 4255T | 92.75 | 0.031 | 47.6 |

| 60 | S. platensis DSM 40041T | S. libani subsp. libani NBRC 13452T | 92.58 | 0.033 | 45.9 |

| 61 | S. glebosus NBRC 13786T | S. libani subsp. libani NBRC 13452T | 92.55 | 0.033 | 45.9 |

| 62 | S. coelicoflavus NBRC 15399T | S. rubrogriseus NBRC 15455T | 92.48 | 0.018 | 45.7 |

| 63 | S. diastaticus subsp. ardesiacus NBRC 15402T | S. coelicoflavus NBRC 15399T | 92.34 | 0.023 | 45.4 |

| 64 | S. libani subsp. libani NBRC 13452T | S. tubercidicus NBRC 13090T | 92.25 | 0.041 | 44.6 |

| 65 | S. violaceusniger NBRC 13459T | S. sporoclivatus NBRC 100767T | 92.09 | 0.033 | 43.5 |

| 66 | S. violaceusniger NBRC 13459T | S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T | 92.08 | 0.033 | 43.4 |

| 67 | S. coelicoflavus NBRC 15399T | S. violaceorubidus NRRL B-16381T | 92.02 | 0.021 | 43.9 |

| 68 | S. decoyicus NRRL 2666T | S. caniferus NBRC 15389T | 91.57 | 0.042 | 41.6 |

| 69 | S. hygroscopicus subsp. hygroscopicus NBRC 13472T | S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T | 91.40 | 0.041 | 42.8 |

| 70 | S. tsukubensis NRRL 18488T | S. qinzhouensis SSL-25T | 91.30 | 0.035 | 39.8 |

| 71 | S. tirandamycinicus HNM0039T | S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T | 91.12 | 0.033 | 39.7 |

| 72 | S. angustmyceticus NBRC 3934T | S. decoyicus NRRL 2666T | 90.89 | 0.042 | 39.4 |

| 73 | S. decoyicus NRRL 2666T | S. libani subsp. libani NBRC 13452T | 90.71 | 0.026 | 38.7 |

| 74 | S. albidochromogenes DSM 41800T | S. flavidovirens DSM 40150T | 90.52 | 0.050 | 38.8 |

| 75 | S. wuyuanensis CGMCC 4.7042T | S. spongiicola HNM0071T | 90.42 | 0.040 | 38.0 |

| 76 | S. durhamensis NRRL B-3309T | S. fodineus TW1S1T | 90.33 | 0.037 | 38.1 |

| 77 | S. platensis DSM 40041T | S. decoyicus NRRL 2666T | 90.20 | 0.039 | 37.0 |

| 78 | S. hyaluromycini NBRC 110483T | S. humi MUSC 119T | 90.15 | 0.042 | 37.3 |

| 79 | S. platensis DSM 40041T | S. caniferus NBRC 15389T | 90.08 | 0.049 | 36.5 |

| 80 | S. decoyicus NRRL 2666T | S. inhibens NEAU-D10T | 90.00 | 0.050 | 36.6 |

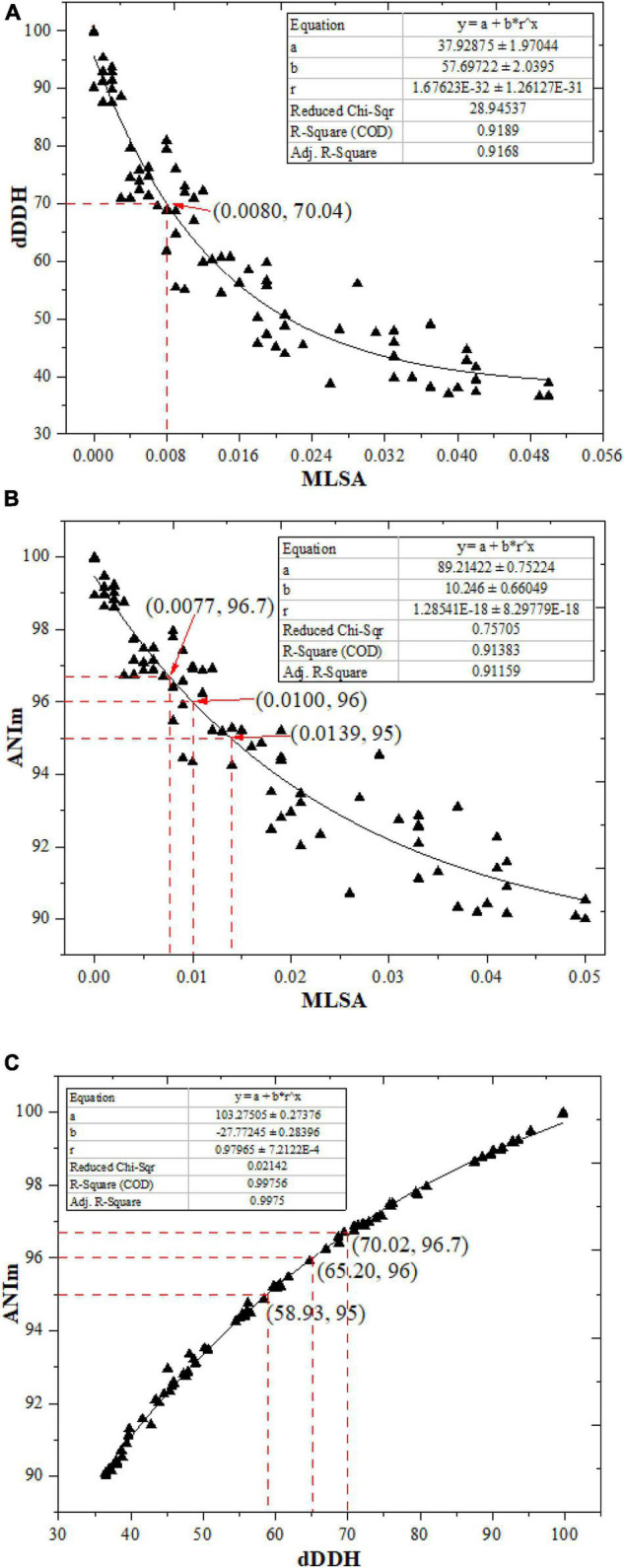

Based on the above analysis, the correlation between dDDH and MLSA, and that between ANIm and MLSA from the aforementioned 80 strain pairs were evaluated by an exponential regression model in order to obtain a more reliable boundary value of MLSA in delineating Streptomyces species. As can be seen in Figure 1A, a 70% dDDH value recommended to delineate species approximately corresponded to a MLSA value of 0.008. Theoretically, the MLSA value should decrease with the increase of dDDH value in the light of the putative boundary of 70% dDDH for species circumscriptions. However, in the present work, there were seven scatter points that deviated from this rule. Therefore, the MLSA value of 0.008 could not be simply used as the boundary for Streptomyces species circumscriptions. Similarly, it may also be clear from Figure 1B that the proposed 95∼96% ANIm value for delineating species approximately corresponded to a MLSA distance range from 0.010 to 0.014. These results suggested that a certain MLSA value could not be used alone as the threshold for the definition of Streptomyces species. Then, what is a more reasonable MLSA value used for defining a Streptomyces species? From Table 1, we found that when the MLSA distance value was greater than or equal to 0.014, each strain pair represented the different genomic species; when the MLSA distance value was less than 0.008, the ANIm and dDDH values between each strain pair (except S. canarius JCM 4733T and S. corchorusii DSM 40340T) were more than the 95∼96% and 70% cut-off points recommended for delineating species, respectively. So, each pair should represent the same genomic species except for S. canarius and S. corchorusii whose taxonomic relationship needed be reevaluated because the dDDH value between them was 69.5%, below 70% boundary point a little, while ANIm value was 96.69%, higher than 95∼96% boundary point. When the MLSA value was between 0.008 and 0.014 (not included), there were seven strain pairs (mentioned above) in which ANIm and dDDH values in each pair were greater than the corresponding thresholds generally accepted by microbial taxonomists, suggesting each pair should represent the same genomic species. In addition, there were nine strain pairs, i.e., S. albidoflavus and S. koyangensis, S. bauhiniae and S. seoulensis, S. rhizosphaericola and S. cavourensis, S. longwoodensis and S. lasalocidi, S. longwoodensis and S. galbus, S. galbus and S. lasalocidi, S. mirabilis and S. olivochromogenes, S. chartreusis and S. osmaniensis, and S. castelarensis and S. melanosporofaciens, whose dDDH values were slightly below the threshold of 70%, suggesting each pair should represent the different genomic species. Nevertheless, there were at least four pairs among the foregoing nine strain pairs, for example, S. albidoflavus and S. koyangensis, S. mirabilis and S. olivochromogenes, S. chartreusis and S. osmaniensis, and S. castelarensis and S. melanosporofaciens, whose ANIm values were slightly greater than the threshold of 95∼96%, suggesting each pair should belong to the same genomic species. Consequently, what are the reasons for the aforesaid contradictory result? In addition, what is the taxonomic relationship between two strains whose dDDH or ANIm values are near the critical points?

FIGURE 1.

The correlations between ANIm, dDDH, and MLSA from the 80 pairs of Streptomyces species (including heterotypic synonyms).

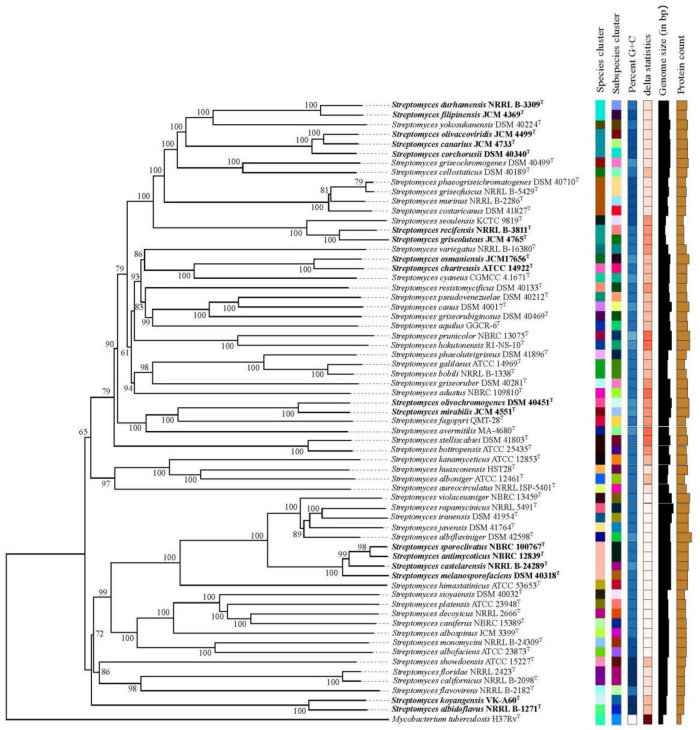

To answer these problems, on the one hand, the correlation between ANIm and dDDH from the aforementioned 80 strain pairs were evaluated by an exponential regression model. It is shown in Figure 1C, the ANIm value revealed an extremely high correlation (R2 = 0.99756) with the dDDH value, further supporting that ANI can accurately replace DDH values for strains whose genome sequences are available (Goris et al., 2007). However, a 70% dDDH value did not correspond to a 95∼96% ANIm value, but to a ANIm value of approximately 96.7%. Thus, the above contradiction can be well explained based on this corresponding relation. On the other hand, the taxonomic relationships of the five strain pairs (S. canarius and S. corchorusii, S. albidoflavus and S. koyangensis, S. mirabilis and S. olivochromogenes, S. chartreusis and S. osmaniensis, and S. castelarensis and S. melanosporofaciens) were reevaluated by using a polyphasic taxonomic approach. At present, it has become a generally accepted principle by biologists to classify living organisms according to the level of phylogenetic correlation since the birth of evolution theory (Ward, 1998). In current prokaryote taxonomy, phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences plays a key role in species discrimination. However, there have been evidence that phylogenomic analysis exhibits better resolution than phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (Rodriguez-R et al., 2018; Duchêne, 2021). In the present work, phylogenetic analysis indicated that there were three strain pairs, i.e., S. albidoflavus CGMCC 4.1291T and S. koyangensis JCM 14915T, S. chartreusis CGMCC 4.1639T and S. osmaniensis JCM 17656T, and S. mirabilis CGMCC 4.7010T and S. olivochromogenes CGMCC 4.2000T, in which each pair did not belong to the same species cluster according to the labeled color in the phylogenomic tree (Figure 2), suggesting that these six Streptomyces species should represent different genomic species. This result has been further confirmed by differential comparisons of cultural, physio-biochemical and chemotaxonomic characteristics in each pair (Supplementary Tables 2–4); with regard to the remaining two pairs, i.e., S. canarius CGMCC 4.1581T and S. corchorusii CGMCC 4.1592T, and S. castelarensis CGMCC 4.3570T and S. melanosporofaciens CGMCC 4.1742T, strains within each pair should belong to the same genomic species according to the phylogenomic clustering patterns (Figure 2). This result could also be confirmed by the facts shown in Supplementary Tables 5–7, the vast majority of phenotypic features of each strain pair were very similar with only a few exceptions. For example, as far as the former pair was concerned, milk coagulation, milk peptization and α-mannosidase activity were negative for strain CGMCC 4.1581T, while positive for strain CGMCC 4.1592T; cellular fatty acids such as iso-C19:0, anteiso-C19:0 and C20:0 were detected for strain CGMCC 4.1592T, while not for strain CGMCC 4.1581T; the major menaquinone in strain CGMCC 4.1592T was MK-9(H8), up to 82.0%, while the major menaquinone in strain CGMCC 4.1581T was MK-9(H6), only 53.6%. As far as the latter pair was concerned, activities of α-chymotrypsin, β-galactosidase and valine arylamidase were positive for strain CGMCC 4.3570T, while negative for strain CGMCC 4.1742T; Assimilation of L-Rhamnose was positive for strain CGMCC 4.3570T, while negative for strain CGMCC 4.1742T; in cellular fatty acids, the percentage composition of Sum In Feature 8 was up to10.5% for strain CGMCC 4.3570T, while only 0.5 for strain CGMCC 4.1742T; moreover, in cultural characteristics, color of aerial mycelia on ISP2 and ISP6 was, respectively, dark mouse gray and grayish white for strain CGMCC 4.3570T, while both white for strain CGMCC 4.1742T. The disagreement for phenotypic characteristics between each strain pair representing the same genomic species was probably due to different ecological niches or minor differences in genotype. All these data supported that 70% dDDH or 96.7% ANIm value could act as the threshold value in delineating Streptomyces species. But when dDDH or ANIm value between two closely related Streptomyces strains was less than but close to 70 or 96.7% cut-off point, the taxonomic status of a novel strain could only be determined by a combination of phenotypic characteristics, chemotaxonomic characteristics and phylogenomic analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenomic tree of five pairs of Streptomyces species and related reference strains. The numbers above branches are GBDP pseudo-bootstrap support values > 60% from 100 replications, with an average branch support of 96.0%. The tree was rooted at the midpoint (Farris, 1972).

Conclusion

Based on the above analysis, on the one hand, a 70% dDDH value did not corresponded to a 95∼96% ANIm value but approximately to a 96.7% ANIm value in the genus Streptomyces. On the other hand, we proposed that when the MLSA distance value between a novel Streptomyces strain and a reference strain was less than 0.008, the novel strain could be considered as a heterotypic synonym of the reference strain; when the MLSA distance value was greater than or equal to 0.014, the novel strain could be regarded as a new Streptomyces species; when the MLSA distance value was between 0.008 and 0.014 (not included), ANIm or dDDH value between a new strain and a reference strain must be calculated in order to determine the taxonomic status of a novel strain. Although 70% dDDH or 96.7% ANIm value could act as the threshold value in delineating Streptomyces species, if dDDH or ANIm value was less than but close to 70 or 96.7% cut-off point, the taxonomic status of a novel strain could only be determined by a combination of phenotypic characteristics, chemotaxonomic characteristics and phylogenomic analysis.

Taxonomic Consequences: Emendations

Streptomyces melanosporofaciens Arcamone et al., 1959 (Approved Lists 1980) Is a Later Heterotypic Synonym of Streptomyces antimycoticus Waksman, 1957 (Approved Lists 1980)

In the present work, the MLSA distance value between S. antimycoticus NBRC 12839T and S. melanosporofaciens DSM 40318T is 0.01, higher than the boundary value of 0.008, but the ANIm and dDDH values between them are 96.9% and 72.0, respectively, greater than the 96.7 and 70% cut-off points recommended for delineating species, supporting that they represent the same genomic species. On the basis of these data and rule 42 of the Bacteriological Code (Parker et al., 2019), we propose that S. melanosporofaciens is a heterotypic synonym of S. antimycoticus.

The description is as given by Komaki and Tamura (2020).

Emended Description of Streptomyces filipinensis (Approved Lists 1980)

Heterotypic synonym: Streptomyces durhamensis Gordon and Lapa, 1966 (Approved Lists 1980).

In the present work, the MLSA distance value between S. filipinensis JCM 4369T and S. durhamensis NRRL B-3309T is 0.01, higher than the boundary value of 0.008, but the ANIm and dDDH values between them are 96.97 and 72.9%, respectively, greater than the 96.7 and 70% cut-off points recommended for delineating species, supporting that they represent the same genomic species. On the basis of these data and rule 42 of the Bacteriological Code, we propose that S. durhamensis is a heterotypic synonym of S. filipinensis.

The description is as given by Ammann et al. (1955) with the following modification. The G + C content of the type-strain genome is 71.8%, its approximate size 9.03 Mbp, its GenBank deposit SAMD00245426.

Emended Description of Streptomyces griseoluteus (Approved Lists 1980)

Heterotypic synonym: Streptomyces recifensis (Gonçalves de Lima et al., 1955) Falcão de Morais et al., 1957 (Approved Lists 1980).

In the present work, the ANIm, dDDH and MLSA distance values between S. recifensis NRRL B-3811T and S. griseoluteus JCM 4765T are 96.86, 72.4, and 0.005, respectively, far away from the 96.7%, 70%, and 0.008 cut-off points recommended for delineating species, supporting that they represent the same genomic species. On the basis of these data and rule 42 of the Bacteriological Code, we propose that S. recifensis is a heterotypic synonym of S. griseoluteus.

The description is as given Umezawa et al. (1950) with the following modification. The G + C content of the type-strain genome is 71.6%, its approximate size 6.51 Mbp, its GenBank deposit SAMD00245512.

Emended Description of Streptomyces olivaceoviridis (Preobrazhenskaya and Ryabova, 1957) (Approved Lists 1980)

Heterotypic synonym: Streptomyces corchorusii Ahmad and Bhuiyan, 1958 (Approved Lists 1980) and Streptomyces canarius Vavra and Dietz, 1965 (Approved Lists 1980).

In the present work, the ANIm, dDDH and MLSA distance values between S. olivaceoviridis JCM 4499T and S. corchorusii DSM 40340T are 96.88, 71.4 and 0.006, respectively, above the 96.7%, 70% and 0.008 cut-off points recommended for delineating species, supporting that they represent the same genomic species. Meanwhile, the ANIm and dDDH values between S. canarius JCM 4733T and S. corchorusii DSM 40340T are 96.69 and 69.5%, respectively, near the 96.7 and 70% boundary points, but the MLSA distance value of them is 0.007, below the 0.008 boundary value recommended for delineating species. In addition, this result is further confirmed by the clustering patterns resulting from phylogenomic analysis. Labeda et al. (2017) also recognized that S. corchorusii NRRL B-12289T is a later heterotypic synonym of S. olivaceoviridis NRRL B-12280T. Thus, On the basis of these data and rule 42 of the Bacteriological Code, we propose that S. corchorusii and S. canaries are latter heterotypic synonyms of S. olivaceoviridis.

The description is as given by Pridham et al. (1958) with the following modification. The G + C content of the type-strain genome is 72.1%, its approximate size 9.53 Mbp, its GenBank deposit SAMD00245462.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

JG and YZ: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SH, YW, LF, and YX: acquisition of data. XT: analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to CICC (China Center of Industrial Culture Collection, Beijing, China) for providing excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ANI

average nucleotide identity

- dDDH

digital DNA–DNA hybridization

- MLSA

multi-locus sequence analysis

- CGMCC

China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre

- JCM

Japan Collection of Microorganisms

- ISP

International Streptomyces Project.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFE0117600) and Scientific Research Project of Hunan Province Department of Education (20A200).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.910277/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ammann A., Gottlieb D., Brock T. D., Carter H. E., Whitfield G. B. (1955). Filipin, an antibiotic effective against fungi. Phytopathology. 45 559–563. [Google Scholar]

- Auch A. F., von Jan M., Klenk H. P., Göker M. (2010). Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2 117–134. 10.4056/sigs.531120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun J., Oren A., Ventosa A., Christensen H., Arahal D. R., da Costa M. S., et al. (2018). Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68 461–466. 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M. D., Pirouz T., Goodfellow M., Minnikin D. E. (1977). Distribution of menaquinones in actinomycetes and corynebacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 100 221–230. 10.1099/00221287-100-2-221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloger M., El Karoui M., Petit M. A. (2009). A genomic distance based on MUM indicates discontinuity between most bacterial species and genera. J. Bacteriol. 191 91–99. 10.1128/Jb.01202-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchêne D. A. (2021). Phylogenomics. Curr. Biol. 31 R1177–R1181. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris J. S. (1972). Estimating phylogenetic trees from distance matrices. Am. Nat. 106 645–667. 10.1086/282802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gevers D., Cohan F. M., Lawrence J. G., Spratt B. G., Coenye T., Feil E. J., et al. (2005). Opinion: re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 733–739. 10.1038/nrmicro1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris J., Konstantinidis K. T., Klappenbach J. A., Coenye T., Vandamme P., Tiedje J. M. (2007). DNA–DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 81–91. 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. P., Zheng W., Rong X. Y., Huang Y. (2008). A multilocus phylogeny of the Streptomyces griseus 16S rRNA gene clade: use of multilocus sequence analysis for streptomycete systematics. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58 149–159. 10.1099/ijs.0.65224-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T., Takizawa M., Tanida S. (1983). A rapid analysis for chemical grouping of aerobic actinomycetes. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 29 319–322. 10.2323/jgam.29.319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henz S. R., Huson D. H., Auch A. F., Nieselt-Struwe K., Schuster S. C. (2005). Whole-genome prokaryotic phylogeny. Bioinformatics 21 2329–2335. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kates M. (1986). Techniques of Lipidology, 2nd Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. (1980). A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16 111–120. 10.1007/BF01731581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komaki H., Tamura T. (2020). Reclassification of Streptomyces castelarensis and Streptomyces sporoclivatus as later heterotypic synonyms of Streptomyces antimycoticus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70 1099–1105. 10.1099/ijsem.0.003882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis K. T., Ramette A., Tiedje J. M. (2006). The bacterial species definition in the genomic era. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 361 1929–1940. 10.1098/rstb.2006.1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinidis K. T., Tiedje J. M. (2005). Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 2567–2572. 10.1073/pnas.0409727102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeda D. P., Dunlap C. A., Rong X., Huang Y., Doroghazi J. R., Ju K. S., et al. (2017). Phylogenetic relationships in the family Streptomycetaceae using multi-locus sequence analysis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 110 563–583. 10.1007/s10482-016-0824-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechevalier M. P., Lechevalier H. (1970). Chemical composition as a criterion in the classification of aerobic actinomycetes. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 20 433–435. 10.1128/jb.94.4.875-883.1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort V., Desper R., Gascuel O. (2015). FastME 2.0: A comprehensive, accurate, and fast distance-based phylogeny inference program. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32 2798–2800. 10.1093/molbev/msv150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K. Q., Guo Y. H., Wang J. Z., Wang Z. Y., Zhao J. R., Gao J. (2020). Streptomyces aquilus sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from a Chinese medicinal plant. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70 1912–1917. 10.1099/ijsem.0.003995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhaiyan M., Saravanan V. S., See-Too W. S. (2020). Genome-based analyses reveal the presence of 12 heterotypic synonyms in the genus Streptomyces and emended descriptions of Streptomyces bottropensis, Streptomyces cellulo?avus, Streptomyces fulvissimus, Streptomyces glaucescens, Streptomyces murinus, and Streptomyces variegatus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70 3924–3929. 10.1099/ijsem.0.004217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Auch A. F., Klenk H. P., Göker M. (2013). Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 14:60. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Göker M. (2019). TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 10:2182. 10.1038/s41467-019-10210-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIDI (2005). Sherlock Microbial Identification System Operating Manual, Version 6.0. Newark DE: MIDI Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Parker C. T., Tindall B. J., Garrity G. M. (2019). International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 69 S1–S111. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pridham T. G., Hesseltine C. W., Benedict R. G. (1958). A guide for the classification of streptomycetes according to selected groups; placement of strains in morphological sections. Appl. Microbiol. 6 52–79. 10.1128/am.6.1.52-79.1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rosselló-Móra R., Glöckner F. O., Peplies J. (2015). JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics 32 681–931. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway R. (1912). Color standards and color nomenclature. Washington, DC: Ridgway, R, 1–43. plate I–LII. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-R L. M., Gunturu S., Harvey W. T., Rosselló-Mora R., Tiedje J. M., Cole J. R., et al. (2018). The Microbial Genomes Atlas (MiGA) webserver: taxonomic and gene diversity analysis of Archaea and Bacteria at the whole genome level. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 W282–W288. 10.1093/nar/gky467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X., Guo Y., Huang Y. (2009). Proposal to reclassify the Streptomyces albidoflavus clade on the basis of multilocus sequence analysis and DNA–DNA hybridization, and taxonomic elucidation of Streptomyces griseus subsp. solvifaciens. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32 314–322. 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X., Huang Y. (2010). Taxonomic evaluation of the Streptomyces griseus clade using multilocus sequence analysis and DNA-DNA hybridization, with proposal to combine 29 species and three subspecies as 11 genomic species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60 696–703. 10.1099/ijs.0.012419-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X., Huang Y. (2012). Taxonomic evaluation of the Streptomyces hygroscopicus clade using multilocus sequence analysis and DNA–DNA hybridization, validating the MLSA scheme for systematics of the whole genus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 35 7–18. 10.1016/j.syapm.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X., Liu N., Ruan J., Huang Y. (2010). Multilocus sequence analysis of Streptomyces griseus isolates delineating intraspecific diversity in terms of both taxonomy and biosynthetic potential. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 98 237–248. 10.1007/s10482-010-9447-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer K. H. (2009). Classification of Bacteria and Archaea: past, present and future. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32 533–542. 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirling E. B., Gottlieb D. (1966). Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 16 313–340. 10.1099/00207713-16-3-313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E., Ebers J. (2006). Taxonomic parameters revisited: tarnished gold standards. Microbiol. Today. 33 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E., Frederiksen W., Garrity G. M., Grimont P. A. D., Kämpfer P., Maiden M. C. (2002). Report of the ad hoc committee for the reevaluation of the species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52 1043–1047. 10.1099/00207713-52-3-1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stackebrandt E., Goebel B. M. (1994). Taxonomic note: a place for DNA–DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 44 846–849. 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall B. J., Rosselló-Móra R., Busse H. J., Ludwig W., Kämpfer P. (2010). Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60 249–266. 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa H., Hayano S., Maeda K., Ogata Y., Okami Y. (1950). On a new antibiotic, griseolutein, produced by streptomyces. Jpn. Med. J. 3 111–117. 10.7883/yoken1948.3.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward D. M. (1998). A natural species concept for prokaryotes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1 271–277. 10.1016/S1369-5274(98)80029-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. H., Lu X. T., Qin M., Wang Y. S., Ruan J. S. (1989). Analysis of menaquinone compound in microbial cells by HPLC. Microbiology 16 176–178. 10.1128/jb.171.7.3619-3628.1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. H., Li W. J., Liu Z. H., Jiang C. L. (2007). Actinomycete Systematic-Principle, Methods and Practice. Beijing: Science press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Wang J. N., Wang J. L., Wang J. J., Li Y. Z. (2020). Estimate of the sequenced proportion of the global prokaryotic genome. Microbiome. 8:134. 10.1186/s40168-020-00903-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.