Abstract

Background:

The vacuolar protein sorting 35 (VPS35) is the main component of the retromer recognition core complex system which regulates intracellular cargo protein sorting and trafficking. Down regulation of VPS35 has been linked to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders such Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease via endosome dysregulation.

Objective:

Here we show that the genetic manipulation of VPS35 affects intracellular degradation pathways.

Methods:

A neuronal cell line expressing human APP Swedish mutant was used. VPS35 silencing was performed treating cells with VPS35 siRNA or Ctr siRNA for 72h.

Results:

Down regulation of VPS35 was associated with alteration of autophagy flux and intracellular accumulation of acidic and ubiquitinated aggregates suggesting that dysfunction of the retromer recognition core leads to a significant alteration in both pathways.

Conclusions:

Taken together, our data demonstrate that besides cargo sorting and trafficking, VPS35 by supporting the integral function of the retromer complex system plays an important role also as a critical regulator of intracellular degradation pathways.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, autophagy pathway, endosomal system, proteosome pathway, retromer complex

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are among the most devastating human illnesses since they have no cure. Multiple genetic loci form the basis of genetic risk factors for the development of several of them [1]. Interestingly, some of the products of these loci are part of fundamental cell biology pathways such as membrane sorting and trafficking, which play a key role in maintaining cell health and homeostasis. Thus, intracellular protein trafficking through the endosome system, composed of various dynamic membrane-enclosed structures such as early endosomes, recycling endosomes, and late endosomes, can drive macromolecules and transmembrane proteins at the plasma membrane or towards degradation [2]. In recent years, dysfunction of the endosome network system has gained a lot of attention in an effort to better understand mechanisms relevant to neurodegeneration and its clinical manifestation such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [3] and Parkinson-’s disease (PD) [4].

The main regulator of endosomal protein sorting and trafficking is the retromer complex, an evolutionarily conserved system that operates the retrograde transport of cargo from the endosome to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) [5]. The system is a multimeric protein complex, comprised of a sorting nexin (SNX) protein and a cargo-recognition core composed by the VPS35/ VPS26/ VPS29/ trimer [6]. Moreover, the cargo recognition core collaborates with actin-nucleating Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and SCAR homolog (WASH) and retriever complexes, and with associated receptors and proteins including cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (CIMPR), Vps10-member sortilin, sortilin-related receptor 1 (Sorl-1; also known as SORLA), glutamate receptors, and sorting nexin-Bar (Snx-BAR) proteins family [7].

Deficiency or mutations in one or more protein components of the retromer complex leads to an increase in the accumulation of protein aggregates as well as in the development of PD- and AD-like phenotype [8,9]. The endosome-to-TGN route via the retromer complex system might also be directly required for two of the most important cellular degradation and recycling pathways: autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) and ubiquitin-proteosome system (UPS) [10]. UPS is responsible for the degradation of most cytosolic and nuclear proteins, including short- and long-lived proteins as well as aberrant proteins, whereas the ALP is specialized in protein aggregates and damaged organelles degradation [11]. A common feature of the two processes is the attachment of polyubiquitin conjugates to proteins that initiate these degradative processes [12]. Recent studies have shown that defects in the ALP and the UPS pathways are likely to precede the formation of protein aggregates such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques or tau neurofibrillary tangles and accumulation of defective organelles [13]. Several studies have reported that retromer dysfunction is correlated to defects in protein sorting and trafficking. However, only a few studies have shown a link between VPS35 deficit and impairments of ALP and/or UPS pathways [14, 15]. In this study, we show that VPS35 deficiency influences autophagy flux and the degradation pathways driven by lysosome and proteasome resulting in reduced substrate degradation.

Material and Methods

Cell culture and transfection

The neuro-2A neuroblastoma (N2A) cells stably expressing human APP carrying the K670 N, M671 L Swedish mutation (APPswe) were cultured as previously described [16]. For down regulation studies, cells were cultured to 70% confluence in six-well plates and then transfected. Briefly, a mixture of opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11058-021) with 100 nM control siRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, AM4621) was prepared and incubated at RT for 5 minutes. Another mixture using opti-MEM with 100 nM of VPS35 siRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4390771) was prepared and incubated for 5 minutes at RT. Both solutions were mixed and incubated for 15 minutes by using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen, 13778-150) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mixture was added to each well (250 μl/well), already containing 1 ml of opti-MEM. After 6 h of incubation, fresh complete medium was replaced. After 72 h, supernatants were collected, and cells were harvested in lysis buffer for biochemistry analyses.

Cell treatments

Cells were exposed to Bafilomycin (BafA1) (Sigma-Aldrich, B1793-10; final concentration: 100 mM) and Borteozomib (BTZ) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, J60378; final concentration: 100 μM) for 4 h.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were used for Western blot analysis as previously described [17]. Briefly, samples were electrophoresed on 10% Bis-Tris gels or 3–8% Tris-acetate gel (Bio-Rad), transferred into nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), and then incubated overnight at 4° C with the appropriate primary antibodies LC3B (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, CST-27755), SQSTM1/p62 (1:500, Abcam, ab 56416), ATG9 (1:300, Abcam, ab 108338), ATG7 (1:300, Cell Signaling Technology, CST 8558S), ATG5 (1:300, Cell Signaling Technology, CST 2630S), VPS35 (1:250, ab 157220, Abcam), VPS26 (1:250, Abcam, ab 23892), VPS29 (1:250, Abcam, ab 10160), ubiquitin (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, CST 3933S), APP (1:500, Millipore, MAB348) and lysosomal membrane proteins 2 (LAMP-2) (1:500, Abcam, ab13524). After three washes with T-TBS (pH 7.4), membranes were incubated with IRDye 800CW-labeled secondary antibodies (LI-COR Bioscience) (anti-mouse 926-32212, anti-rabbit 926-32211, anti-goat 926-32214) at room temperature for 1 h. Signals were developed with Odyssey Infrared Imaging Systems (LI-COR Bioscience). GAPDH (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, CST 2118S) was always used as internal loading control.

Biochemical analysis

After 72 h transfection, cell supernatants were collected for Aβ 1–40 measurement by a sensitive ELISA kit (Invitrogen, KHB3481) as previously described [18].

Immunofluorescence analysis (IF)

The N2A-APPswe cells were cultured on glass coverslips, and treated with control siRNA or VPS35 siRNA, as previously described [8]. Briefly, after rinsing with PBS 1X, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Cells were treated with 10% donkey serum/PBS approximately for 25 min, and then incubated with LC3B primary antibody (1:250), and p62 (1:250) overnight at 4°C. After rinsing with PBS 1X, cells were incubated with the Alex Fluor 488/568-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:300) (Abcam, anti-goat ab 150133, anti-mouse ab 175700, anti-rabbit ab 175693) for 30 min, 37°C. The nucleus was stained with diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI solution) (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 62248). Coverslips were mounted using ProLong™ Glass Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36980) and images were taken by using Olympus BX60 fluorescent microscope (Olympus) with 100× objective.

LysoTracker Red staining

The N2A-APPswe cells were cultured on glass coverslips, and treated with control siRNA or VPS35 siRNA, as described above. After PBS 1X rinsing, cells were incubated with 75 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L7528) in 10% Donkey serum for 90 min at RT followed by washing with fresh PBS 1X. Subsequently, cells were fixed as described above. Coverslips were mounted and all images were taken by using Olympus BX60 fluorescent microscope (Olympus) with 100× objective.

Statistical analysis

All the data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and presented also as individual data values. Comparisons between two groups were made using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. Comparisons between more than two groups were made using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferoni’s multiple comparisons test. The p-values for each comparison are listed in each figure legend with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Effect of VPS35 down regulation on retromer recognition core proteins and Aβ levels

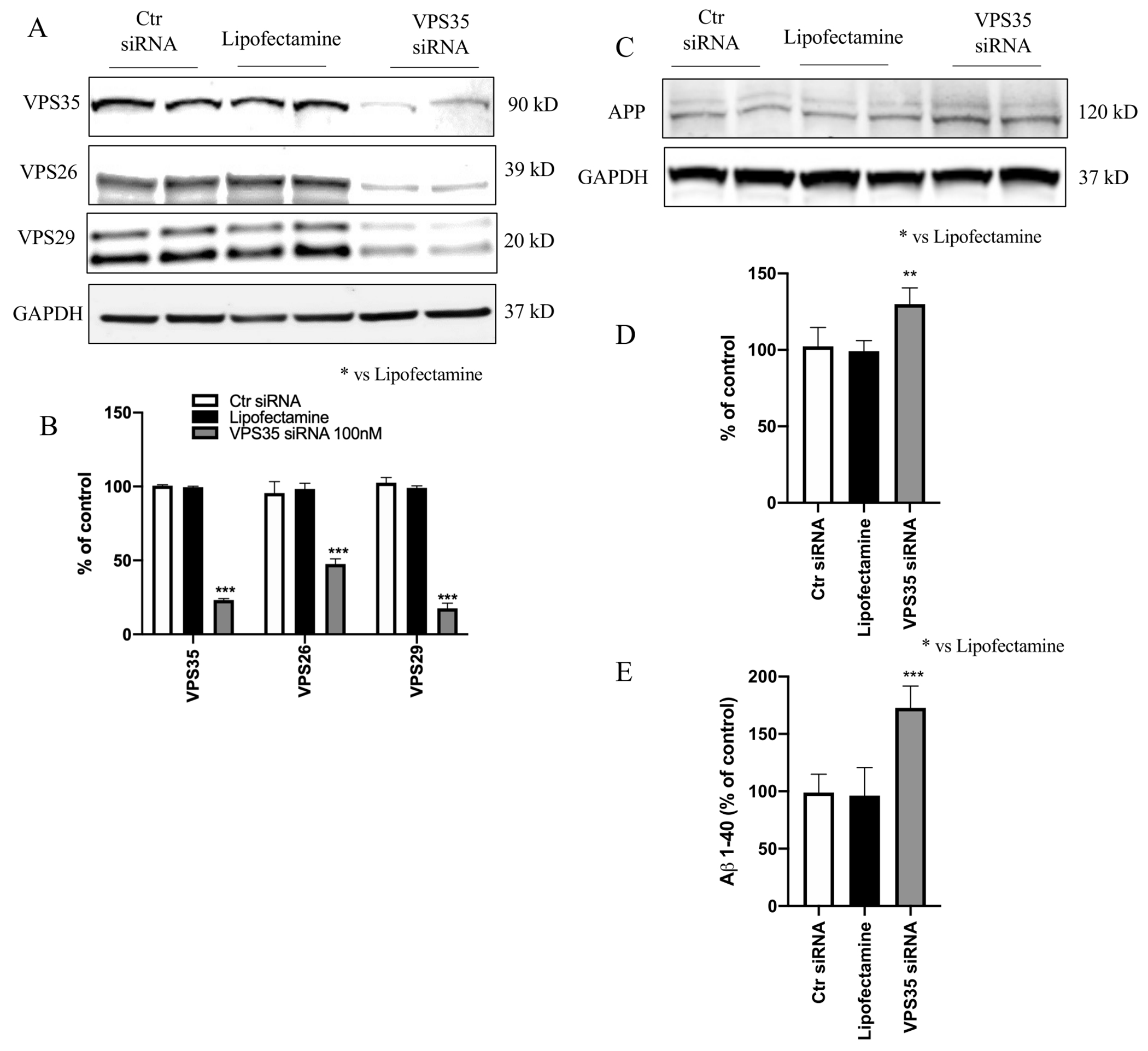

VPS35 is important for regulating endosome-to-TGN and endosome-to-cell surface trafficking of proteins [19]. To monitor whether VPS35 silencing also modulated the other retromer core components levels, we down regulated VPS35 and investigated its effect on VPS26 and VPS29 expression levels in N2A APPswe cells. We confirmed the efficiency of the VPS35 gene silencing by Western blot analysis showing a ~70% decrease in its protein levels, which was associated also with a significant decrease in VPS26, and VPS29 levels (Figure 1 A, B).

Figure 1. VPS35 silencing decreases expression of retromer recognition core components.

A) N2A-APPswe cells were transfected with VPS35 siRNA or controls (Lipofectamine, scramble siRNA) for 72 h, then harvested. Representative Western blot analysis for VPS35, VPS26 and VPS29. B) Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactivity to the antibodies shown in the previous panel. C. Representative Western blot of APP protein in N2A-APPswe cells transfected with VPS35 siRNA or controls (Lipofectamine, scramble siRNA). D. Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivities to the antibodies shown in the previous panel. E. Aβ1–40 levels in conditioned media from cell transfected with VPS35 siRNA or Ctrl siRNA were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (** p < 0.01 vs Lipofectamine; **** p < 0.0001 vs Lipofectamine). All results are mean ± SEM (N=2 per groups, three individual experiments).

To assess the effect of VPS35 on Aβ formation and APP levels, supernatants were collected and assayed for Aβ 1–40, while cell lysates used for Western blot analysis, respectively. Compared with controls, we observed that the cells transfected with VPS35 siRNA had a significant increase in steady state levels of APP protein (Figure 1 C, D), which was accompanied by a significant elevation of Aβ 1–40 peptide levels (Figure 1 E).

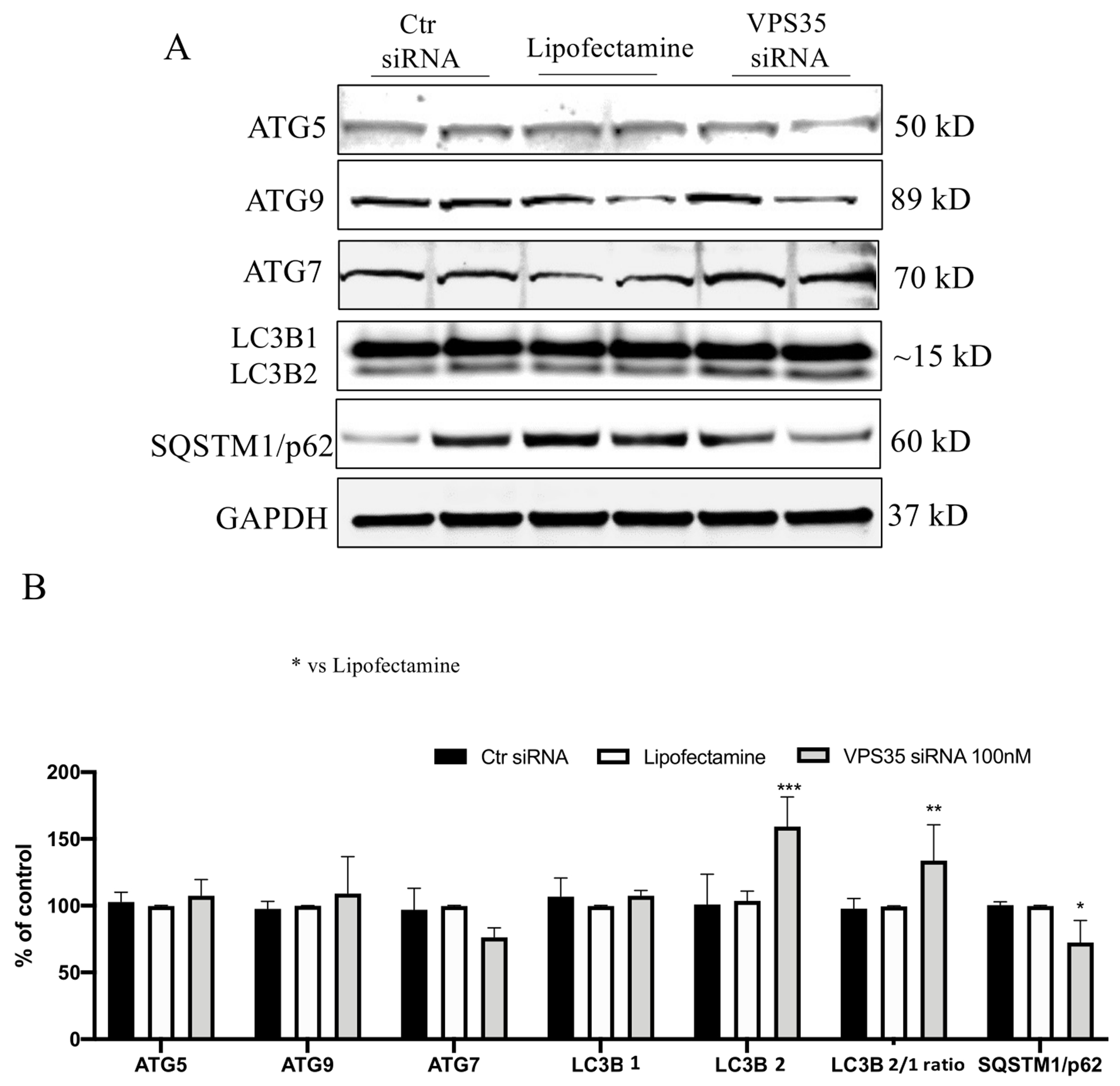

VPS35 down regulation enhances LC3B2 expression

After determining that the retromer recognition complex proteins were down-regulated following gene silencing of VPS35, we investigated whether these changes had any influence on the autophagy process and the canonical autophagosome formation by looking at the effect on autophagy-related proteins (ATGs) [20]. No significant differences were observed among Ctr siRNA, Lipofectamine and VPS35 siRNA groups when we assessed for the ATG5, ATG9, and ATG7 protein levels (Figure 2 A, B). Given that VPS35 down-regulation did not result in any changes of ATGs protein levels, we next investigated the effect on autophagic flux by assessing LC3B levels in the same samples. While we found that the VPS35 silencing did not influence LC3B1 protein levels, by contrast LC3B2 and LC3B2/1 ratio expression were significantly increased when compared to the Lipofectamine group. Under the same experimental condition, these changes were associated with a significant reduction of p62 expression levels (Figure 2 A, B).

Figure 2. Autophagy pathway evaluation following VPS35 silencing.

A) Representative Western blots for ATGs proteins, LC3B and SQSTM1/p62 in N2A-APPswe cells transfected with VPS35 siRNA or controls (Lipofectamine, scramble siRNA). B) Densitometric analyses of the immunoreactivity to the antibodies shown in panel A (* p< 0.05 vs Lipofectamine; ** p< 0.001 vs Lipofectamine; *** p< 0.001 vs Lipofectamine) C) All results are mean ± SEM (N=2 per groups, three individual experiments).

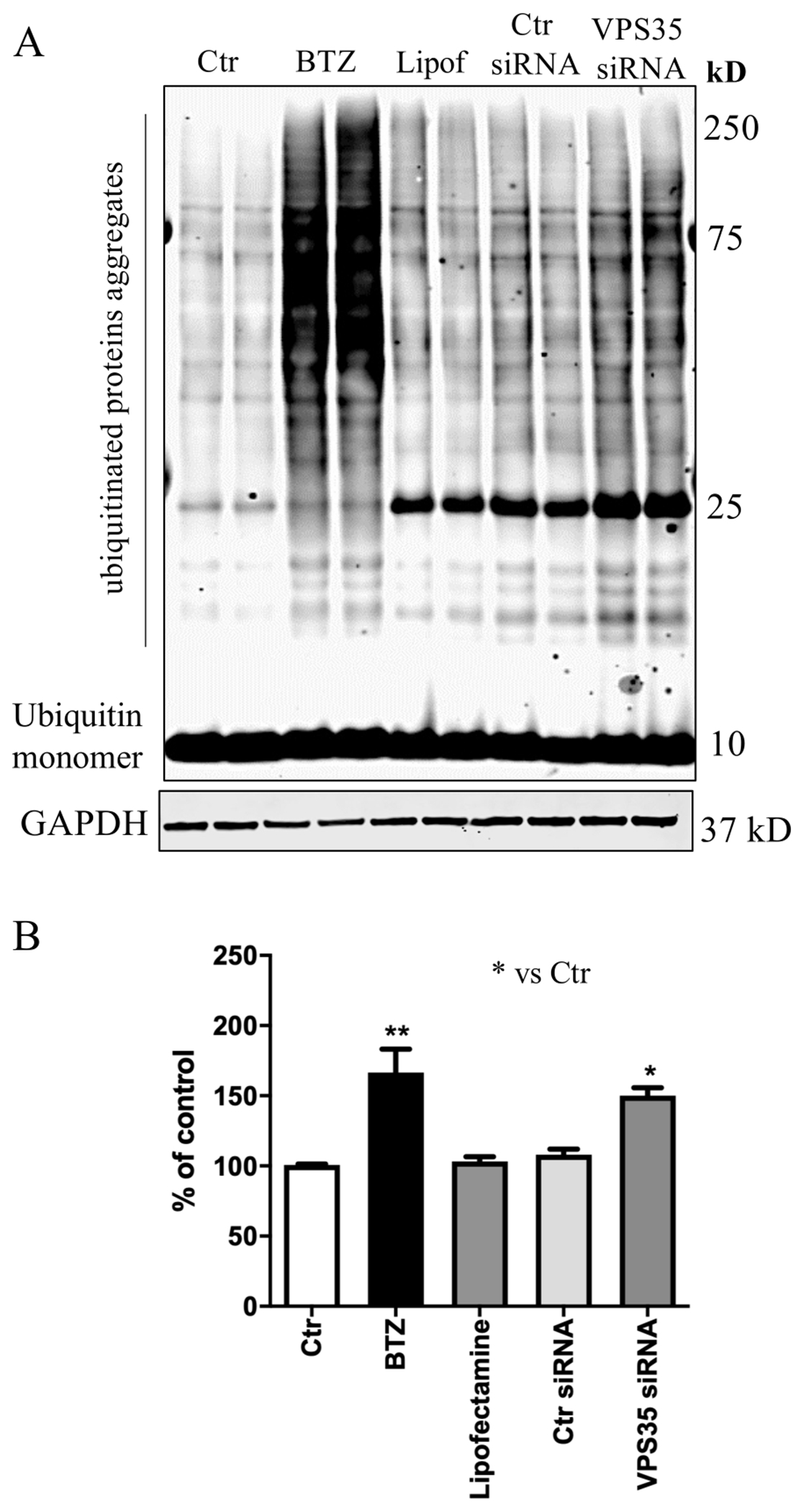

VPS35 down regulation increases ubiquitination

UPS and autophagy are the two major degradation and recycling systems in mammals. Studies have reported a strong interconnection between these two systems by showing that perturbations of one can affect the other [10]. To study the effect of VPS35 down-regulation on the UPS system first we used BTZ, a known proteasome inhibitor, as positive controls in N2A-APPswe cells. Consistent with previous studies, BTZ treatment resulted in an increase of ubiquitinated proteins when compared with control cells (Figure 3 A, B). Interestingly, VPS35 down regulation also resulted in an overall increase in protein ubiquitinylation when compared to control cells, suggesting that retromer complex dysfunction results in alteration of UPS system (Figure 3 A, B).

Figure 3. The process of ubiquitination following VPS35 silencing.

A) Representative Western blot for Ubiquitin. Increased level of poly-ubiquitinated proteins levels following VPS35 silencing. B) Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactivity to Ubiquitin antibody (* p< 0.05 vs Ctr; ** p < 0.001 vs Ctr). All results are mean ± SEM (N=2 per groups, three individual experiments).

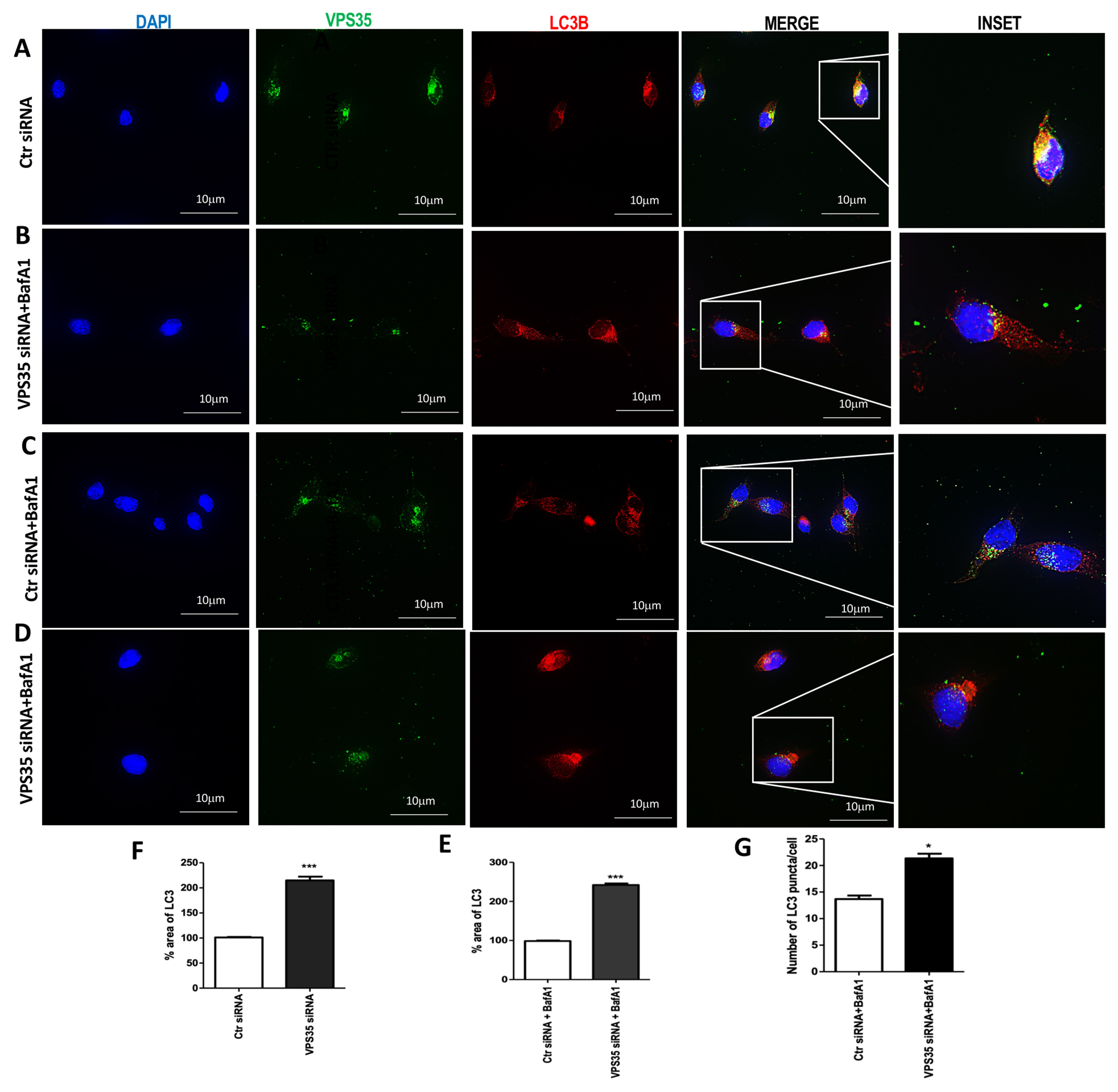

VPS35-deficient cells show aberrant LC3 immunoreactivity

While characterizing the effect of VPS35 silencing on N2A-APPswe cells by IF analysis, we found that LC3B positive immunolabeled cells over the selected area were significantly increased in VPS35-siRNA-treated cells (Figure 4 B, E) when compared to control cells (Figure 4 A, E). Moreover, following BafA1 treatment (which inhibits autophagosome-lysosome fusion) LC3-positive cells were increased in VPS35 siRNA-treated cells (Figure 4 D, F) compared to control siRNA (Figure 4 C, F). Interestingly, following BafA1 treatment, cells with VPS35 down regulation had abundant red-punctate positive structures (Figure 4 D, G), compared to controls (Figure 4 C, G), suggesting autophagosomes accumulation within these cells.

Figure 4. Immunofluorescent analysis of LC3B following VPS35 silencing.

Representative images of control cells (A) and VPS35 silenced (B) for VPS35 (FITC channel, green), LC3B (TXred) and nuclear stain DAPI (blue) LC3B ICC of BafA1-treated control cells (C) and VPS35 silenced cells (D). Representative images showing the morphology of LC3B-positive structures (yellow arrows) in N2A-APPswe cells transfected with VPS35 siRNA or controls (Lipofectamine, scramble siRNA) (C and D) (Scale bar: 10 μm) Percentage area of LC3B (E and F) (*** p < 0.001 vs Ctr siRNA). Quantification of the LC3B puncta cells average number over total cell number (G) (* p < 0.05 vs Ctr siRNA). Data are from three individual experiments.

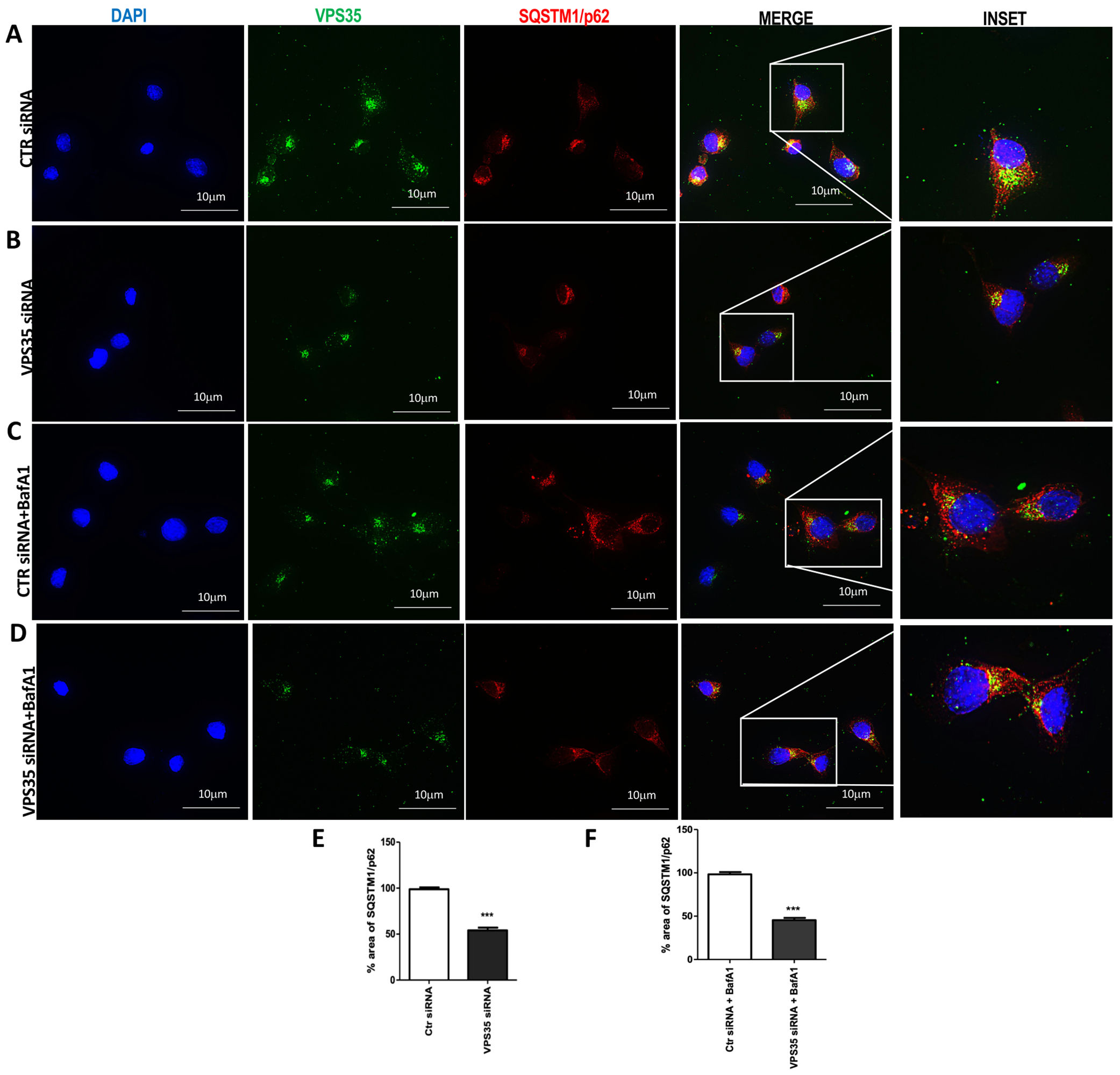

SQSTM1/p62 changes following VPS35 down regulation

An alternative method for assessing cellular autophagic flux is the measure of p62 degradation, since it can bind to LC3 and by doing so serving as a selective substrate of autophagy. First, to further confirm VPS35 silencing efficiency, we performed IF staining using VPS35 antibody following 72 h of transfection (Figure 5 A to D, VPS35 column). Next, we labeled the cells with an antibody against p62. Compared to control cells (Figure 5 A), VPS35 siRNA-treated cells showed a decreased p62 positivity (Figure 5 panel B-E). Moreover, co-treatment of the cells with BafA1, which disables last stage of autophagy, attenuated p62 positives aggregates following VPS35 silencing (Figure 5 C, F) compared to control siRNA-treated cells (Figure 5 D, F), suggesting impaired autophagy.

Figure 5. Immunofluorescence analysis of p62 following VPS35 silencing in N2A-APPswe cells.

Representative images of control cells (A) and VPS35 silenced (B) for VPS35 (FITC channel, green), LC3B (TXred) and nuclear stain DAPI (blue). p62 ICC analysis of BafA1-treated control cells (C) and VPS35 silenced cells (D) (Scale bar: 10 μm). Percentage area of p62 (E and F) (*** p < 0.001 vs Ctr siRNA). Data are from three individual experiments.

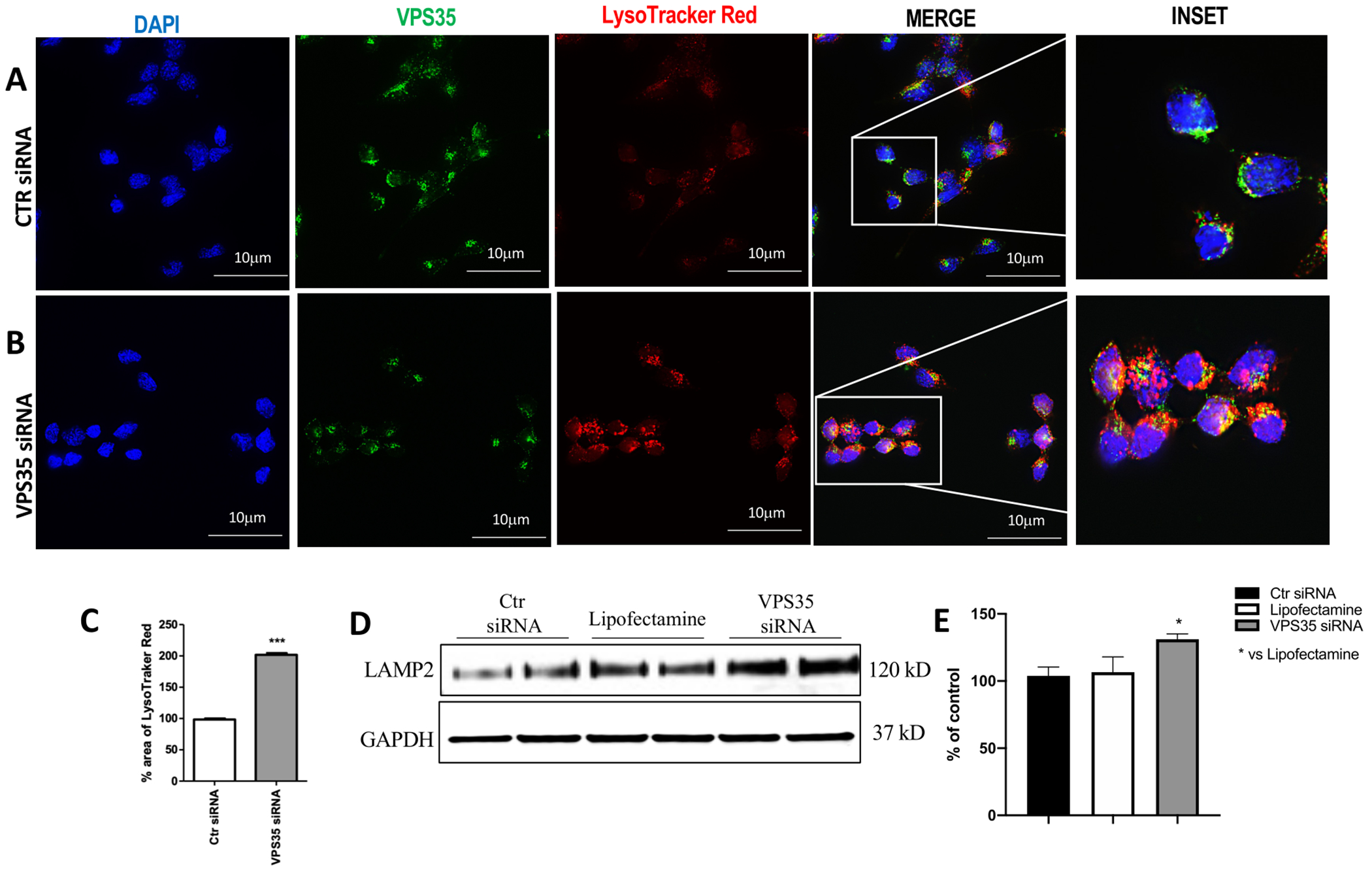

VPS35 down regulation leads to impaired acidic vesicles accumulation

The impairment of autophagic flux in N2A-APPswe cells following VPS35 silencing could be reflected by the accumulation or defects in acidic vesicles such as lysosomes, autophagosomes, and endosomes. LysoTracker Red (LT), a live cell dye, was used to detect abnormalities in vesicular pH and to examine the efficiency of autophagosome/lysosome fusion in our cells [21]. In the presence of LT, control cells (Figure 6 A) showed no apparent changes in LT positivity, reflecting unaltered lysosomal acidity. However, a remarkable increase and accumulation in positive acidic structures were detected in cells following VPS35 down regulation (Figure 6 A, C). Thus, since LT cells positivity reflects changes in the pH of autophagy structure, this finding suggests that retromer complex defects lead to alteration of the autophagy-dependent degradation process.

Figure 6. LysoTracker Red (LT) staining following VPS35 silencing.

Control cells (A) or VPS35 siRNA-treated cells (B) labeled for VPS35 (FITC channel, green) antibody and LT live cells dye (TXred channel, red). The distribution of acidic vesicles was visualized using fluorescence microscopy (100× magnification) (Scale bar: 10 μm). Percentage area of LT (C) (*** p < 0.001 vs Ctr siRNA). Representative Western blot for LAMP-2 protein in N2A-APPswe cells transfected with VPS35 siRNA or controls (Lipofectamine, scramble siRNA) (D). Densitometric analysis of the immunoreactivity to LAMP-2 antibody (* p< 0.05 vs Lipofectamine) (E). All results are mean ± SEM (N=2 per groups, three individual experiments). Data are from three individual experiments.

Effect of VPS35 downregulation on lysosomes

Since endocytic-lysosomal alterations are considered an underlying potential pathological mechanism of AD-associated Aβ accumulation [22] [23], Western blot analysis was performed to investigate the effect of VPS35 knockdown on lysosome membrane protein. As shown in figure 6, we found that VPS35 down regulation resulted in a significant increase of LAMP2 levels compared with control cells (Figure 6, D and E).

Discussion

The traffic of protein cargoes is a very dynamic and specific process between the TGN and the endosomes, also known as the endosomal system, and plays an important role in the health of a cell by controlling protein cargo sorting, recycling, and degradation pathways. The retromer complex is a highly specialized endosomal system directly involved in these processes and its dysfunction could hypothetically lead to a reduced degradation process and an increase of the number of unwanted proteins inside the different cell compartments. VPS35 is known to be needed for the recruitment and stability of the retromer recognition core complex in association with two other proteins, namely VPS26 and VPS29. Several studies have shown that VPS35 genetic manipulation negatively influences the complex assembly, thus, influencing the expression of VPS26 and VPS29 and ultimately destabilizing the entire complex [24] [25]. Interestingly, recent studies support a functional role for the retromer complex system in regulating the accumulation of misfolded α-synuclein protein in PD [26], amyloid-beta in AD, and tau protein in primary tauopathies [18, 27], suggesting indirectly that VPS35 deficit leads to an alteration not only of protein sorting and/or trafficking but possibly of the degradation pathways for these proteins as well.

Within each cell, the ALP and UPS systems represent two major pathways for degradative processes and act as master regulators for overall protein homeostasis, which is crucial for most of the normal cellular functions ranging from apoptosis to cell division and responses to stress.

The ALP system is considered an important and common intracellular degradation pathway by which pathologically altered or aged organelles, long-lived proteins or unnecessary cytosolic contents are enclosed, digested and then, delivered to the lysosomes [28]. Usually, autophagy has been viewed as a process for nonspecific degradation, but it is also involved in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis by degrading pathogens and protein aggregates [29]. An interrelationship exists between endosomal system defects and autophagy, but the relative roles of each pathway in regulating the intracellular degradation processes are still unclear [30,31]. Here, we provide experimental evidence supporting a role for VPS35 in the modulation of this degradation pathway with significant implications for the pathogenesis of AD and other neurodegenerative disorders. Thus, by using the N2A-APPswe cell line, a well-established in vitro experimental model of AD-like amyloidosis, we demonstrated a link between the retromer complex, in particular the VPS35 recognition core component, and the degradation process at different steps. First, we confirmed that in our neuronal cells the genetic downregulation of VPS35 caused a decrease of the other two protein components of the retromer recognition core: VPS26 and VPS29 proteins. To start establishing a link between the retromer complex defects and the autophagy pathway, we considered some of the canonical ATGs proteins which were unchanged by VPS35 silencing. However, it is interesting to note that while we were not able to observe any changes in these proteins, under the same experimental condition we observed significant alterations of LC3B and SQSTM1/p62 protein expression levels. The LC3B and SQSTM1/p62 proteins were investigated because they are considered biological markers for the involvement of autophagy. In fact, we found that VPS35 deficiency was associated with LC3B lipidation process from LC3B1 to LC3B2 form and the accumulation of autophagosome structures [32]. Moreover, SQSTM1/p62 expression was decreased in VPS35 downregulating cells, further confirming an activation of the autophagy pathway [33].

The UPS system is another major pathway responsible for the degradation of unwanted or pathologically folded proteins. The system operates by the ubiquitination of a target protein via a sequential and energy dependent process involving different enzymatic activities (enzyme activating E1, conjugating E2, and ligase E3) before entering the proteasomes for final digestion.

Crosstalk between the UPS and autophagy in the clearance of abnormally folded proteins has been reported in various diseases like neurodegenerative disorders and cancer [34–36]. Importantly, both systems have been shown to be altered at the same time in several neurodegenerative diseases. For example, early pathological changes including endosomal compartments defects, accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, and genetic variants of UPS regulators have been associated with AD [15]. In this regard, we also looked at the UPS, which is strongly involved in the selective elimination and degradation of unwanted proteins [16]. Interestingly, we found that in neuronal cells the poly-ubiquitinated proteins were prominently increased following VPS35 silencing, confirming that VPS35 deficits may negatively influence the UPS machinery resulting in progressive protein aggregation and accumulation. Because of the intricate nature of the biologic link between UPS and ALP we can envision different scenarios to explain our results. The first one would support the hypothesis that VPS35 directly affects ALP which in turn influences the UPS system, the second would imply that VPS35 downregulation would instead directly impair the UPS which then would modulate the late phases of autophagy (conversion of LC3B1 to LC3B2). Although less likely, we can also hypothesize that downregulation of VPS35 dependent effects on ALP and UPS system are totally independent from each other. Further studies will address this important biological question.

Based on these results and in an attempt to localize and visualize the perturbated autophagy proteins compared to the normal protein turnover, firstly, we performed immunocytochemistry to show that VPS35 downregulation resulted in increased fluorescence intensity for LC3B and decrease for p62. Next, in order to determine the effect on lysosome-dependent degradation we measured the autophagy flux by using bafilomycin A1 (BafA1), a potent Vacuolar-ATPase inhibitor [17]. Following VPS35 silencing and BafA1 exposure, neuronal cells showed a prominent increase in LC3B fluorescent puncta, which recognize autophagosome structures, but a significant attenuation of cell positivity for p62.

Since the fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes is the final step of the ALP degradation pathway, we decided to evaluate the distribution of acidic vesicles (i.e., autophagosomes, lysosomes, endosomes, autophagolysosomes) under our experimental condition using the LysoTracker red dye, which is highly permeable to cell membranes and concentrates specifically in acidic organelles. This colorimetric approach is well established and has been widely used to study and visualize lysosomes in living cells [37]. Compared with controls, we found that down-regulation of VPS35 resulted in an increase of fluorescent intensity of the LysoTracker signal, supporting the concept that the cells had an increase in the acidic compartments, including lysosomes and autolysosomes. Importantly, we further confirmed that VPS35 downregulation resulted in an accumulation of phagosomes structures by showing that it associated indeed with a significant increase in the levels of a specific lysosomal membrane protein LAMP2 [38, 39].

In summary our findings provided strong experimental support for the notion that defects in retromer complex system, in particular dysregulation of the retromer recognition core secondary to VPS35 downregulation, influences two of the most important cell degradation pathways (i.e, ALP and UPS), which independently or in combination could ultimately contribute to the development of AD-related neuropathological changes and disease progression. Because the endosomal dysfunction is a well-known and probably early cellular event characteristic of many neurodegenerative diseases, our study further strengthens the concept that VPS35 should be considered an excellent therapeutic target against them.

Acknowledgements

Domenico Praticò is the Scott Richards North Star Charitable Foundation Chair for Alzheimer research. The work described in the article was in part supported by grants for the National Institute of Health (AG055707, and AG056689).

Abbreviations:

- VPS

Vacuolar protein sorting

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- N2A

Neuro-2A neuroblastoma

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- SQSTM1 or p62

Sequestrosome-1

- MAP1-LC3B or LC3B

Microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B

- ALP

Autophagy-lysosome pathway

- UPS

Ubiquitin-proteosome system

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- TGN

Tran-Golgi network

- BafA1

Bafilomycin A1

- BTZ

Borteozomib

- ATG

Autophagy-related protein

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Tsuji S (2010) Genetics of neurodegenerative diseases: insights from high-throughput resequencing. Hum Mol Genet 19, 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lamb CA, Dooley HC, Tooze SA (2013) Endocytosis and autophagy: Shared machinery for degradation. Bioessays 35, 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].O’Brien RJ, Wong PC (2011) Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Neurosci 34, 185–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bono K, Hara-Miyauchi C, Sum S, Oka H, Iguchi Y, Okano JH (2020) Endosomal dysfunction in iPSC-derived neural cells from Parkinson’s disease patients with VPS35 D620N. Mol Brain 13, 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Seaman M (2012) The retromer complex – endosomal protein recycling and beyond. J Cell Sci 125 (20), 4693–4702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Haft CR, Luz Sierra M, Bafford R, Lesniak MA, Barr VA, Taylor S (2000) Human orthologs of yeast vacuolar protein sorting proteins Vps26, 29, and 35: assembly into multimeric complexes. Mol Biol Cell 11, 4105–4116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Teasdale RD, Collins BM (2012) Insights into the PX (phox-homology) domain and SNX (sorting nexin) protein families: structures, functions, and roles in disease. Biochem Journal 441(1), 39–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vagnozzi A, Praticò D (2019) Endosomal sorting and trafficking, the retromer complex and neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry 24, 857–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Small SA, Kent K, Pierce A, Leung C, Kang MS, Okada H, Honig L, Vonsattel JP, Kim TW (2005) Model-guided microarray implicates the retromer complex in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 58, 909–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kocaturk NM, Gozuacik D (2018) Crosstalk between mammalian autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Front Cell Dev Biol 6, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Collins GA, Goldberg AF (2017) The logic of the 26S proteasome. Cell 169(5),792–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bustamante H, González AE, Cerda-Troncoso C, Shaughnessy R, Otth C, Soza A, Burgos PV (2018) Interplay between the autophagy-lysosomal pathway and the ubiquitin-proteasome system: a target for therapeutic development in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci 12, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dantuma NP, Bott LC (2014) The ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases: precipitating factor, yet part of the solution. Front Mol Neurosci 7, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tang FL, Zhao L, Zhao Y, Sun D, Zhu XJ, Mei L, Xiong WC (2020) Coupling of terminal differentiation deficit with neurodegenerative pathology in Vps35-deficient pyramidal neurons. Cell Death & Differentiation 27, 2099–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cao J, Zhong MB, Toro CA, Zhang L, Cai D (2019) Endo-lysosomal pathway and ubiquitin-proteasome system dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neuroscience Lett 703, 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Juenemann K, Schipper-Krom S, Wiemhoefer A, Kloss A, Sanz AS, Reits EAJ (2013) Expanded polyglutamine-containing N-terminal huntingtin fragments are entirely degraded by mammalian proteasomes. J Biol Chem 288, 27068–27084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dhungel N, Eleuteri S, Li LB, Kramer NJ, Chartron JW, Spencer B (2015) Parkinson’s disease genes VPS35 and EIF4G1 interact genetically and converge on α-synuclein. Neuron 85, 76–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li JG, Chiu J, Praticò D (2020) Full recovery of the Alzheimer’s disease phenotype by gain of function of vacuolar protein sorting 35. Mol Psychiatry 25, 2630–2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [19].Wang C, Niu M, Zhou Z, Zheng X, Zhang L, Tian Y, Yu X, Bu G, Xu H, Qilin M, Zhanga Y (2016) VPS35 regulates cell surface recycling and signaling of dopamine receptor D1. Neurobiol Aging 46, 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim E, Lee Y, Lee HJ, Kim JS, Song BS (2010) Implication of mouse VPS26b-VPS29-VPS35 retromer complex in sortilin trafficking. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 403(2), 167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y (2011) The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27, 107–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ling D, Magallanes M, Salvaterra PM (2014) Accumulation of amyloid-like Aβ1–42 in AEL (Autophagy–Endosomal–Lysosomal) vesicles: potential implications for plaque biogenesis. ASN Neuro 6 (2), 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nixon RA (2017) Amyloid precursor protein and endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: inseparable partners in a multifactorial disease. Alzheimer’s Disease Review Series 31, 2729–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Reitz C (2018) Retromer dysfunction and neurodegenerative disease. Curr Genomics 19(4), 279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ye H, Ojelade S, Li-Kroeger D, Zuo Z, Wang L, Li Y, Gu J, Tepass U, Rodal HJ, Shulman JM (2020) Retromer subunit, VPS29, regulates synaptic transmission and is required for endolysosomal function in the aging brain. eLife 9, e51977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Williams ET, Chen X, Moore DJ (2017) VPS35, the retromer complex and Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 7, 219–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vagnozzi A, Li JG, Chiu J, Razmpour R, Warfield R, Ramirez S, Praticò D (2019) VPS35 regulates tau phosphorylation and neuropathology in tauopathy. Mol Psychiatry 10.1038/s41380-019-0453-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [28].Kenney DL, Benarroch EE (2015) The autophagy-lysosomal pathway. General concepts and clinical implications. Neurology 85(7), 634–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Levine B, Kroemer G (2019) Biological functions of autophagy genes: a disease perspective. Cell 176(1-2), 11–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sweeney P, Park H, Baumann M (2017) Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: implications and strategies. Transl Neurodegener 6, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Filippone A, Praticò D. (2021) Endosome dysregulation in Down syndrome: a potential contributor to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann Neurol 90(1), 4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T, Kominami E (2005) Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy 1, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pursiheimo JP, Rantanen K, Heikkinen P (2009) Hypoxia-activated autophagy accelerates degradation of SQSTM1/p62. Oncogene 28(3), 334–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang X, Li Y, Li J, Li L, Zhu H, Chen H, Kong R, Wang G, Wang Y, Hu J, Sun B (2019) Cell-in-cell phenomenon and its relationship with tumor microenvironment and tumor progression: a review. Front Cell Dev Biol 7, 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wang Y, Le WD (2019) Autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome system. Adv Exper Med Biol 1206, 527–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nam T, Han JH, Devkota S, Lee HW (2017) Emerging paradigm of crosstalk between autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Mol Cells 31;40(12):897–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Massalha W, Markovits M, Pichinuk E, Feinstein-Rotkopf Y, Tarshish M, Mishra K, Llado V, Weil M, Escriba PV, Kakhlon O (2019) Minerval (2-hydroxyoleic acid) causes cancer cell selective toxicity by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation and compromising bioenergetic compensation capacity. Biosci Rep 39(1), BSR20181661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Eskelinen EL (2006) Roles of LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 in lysosome biogenesis and autophagy, Mol Asp Med 27, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chi C, Leonard A, Knight W, Kevin M, Beussman, Zhao Y, Cao Y, Londono P, Aune E, Trembley MA, Small E, Jeong M, Walker LA, Xu H, Sniadecki J, Taylor M, Buttrick PM, Song K (2019) LAMP-2B regulates human cardiomyocyte function by mediating autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116 (2), 556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]