ABSTRACT

This study aimed to investigate the changes in the willingness of guardians to administer the COVID-19 vaccine to their children, allow the coadministration of other vaccines, and administer the COVID-19 vaccine booster dose. This was a follow-up study conducted 6 months after a similar previous study. The self-administered questionnaire was distributed through the “Xiao Dou Miao” app and 9424 guardians with access to this app participated in the survey that was conducted from September 15 to October 8, 2021. Of all the participating guardians, 86.68% were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine, which was approximately 16% more than those in our previous study. Guardians aged ≥40 years, healthcare workers, and those with children aged ≥3 years were more willing to vaccinate their children. Approximately 77% of the guardians were willing toward the coadministration of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines. Approximately 64% of the guardians were willing toward the coadministration of other nonimmunization program vaccines with the COVID-19 vaccine for their children. The primary reasons for reluctance toward the coadministration of vaccines were concerns about vaccine safety and effectiveness. If necessary, 92% of the guardians were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster and 82% were willing to vaccinate their children with a COVID-19 vaccine booster. We hope that this research will facilitate the formulation of successful strategies for the implementation of COVID-19 vaccinations, covaccinations, and COVID-19 booster doses, particularly for children aged <6 years.

KEYWORDS: Children, willingness toward vaccination, coadministration, COVID-19 vaccine booster

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a formidable challenge to public health. As a powerful tool in the fight against the pandemic, vaccines have been developed and approved for use at an unprecedented speed in compliance with regulatory procedures.1 With the development of COVID-19 vaccines and the gradual vaccination of the world’s population, children make up a growing proportion of the unvaccinated population.2 However, with COVID-19 not yet contained, the unvaccinated population is at the greatest risk of contracting the illness. At the time of writing, the World Health Organization (WHO) approved ten COVID-19 vaccines for emergency use.3 China approved the emergency use of the COVID-19 inactivated vaccine in children aged 3–17 years on 11 June 2021.4 Vaccination of children aged 12–17 years is ongoing.5 As of 21 January 2022, 2.866 million doses have been administered to individuals aged 3‒11 years in Beijing and 1.511 million individuals have been completely vaccinated.6 The United States, Europe, Singapore, Canada, Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and many other countries have also approved emergency COVID-19 vaccination of 12–17-year-olds.7 WHO has defined vaccine hesitancy as “refusal of vaccines despite the availability of vaccine services”.8 There have been numerous studies about COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in adults, but there are few studies on the vaccine hesitancy of guardians regarding the vaccination of their children. The research on this topic thus far has found that parental willingness to allow vaccination of their children is low. However, the sample sizes of these studies were small.9–11 From the perspective of herd immunity, protection from the vaccine in the form of immunity and vaccine coverage go hand in hand and must be achieved simultaneously.

We previously surveyed guardians of children aged <6 years and found that approximately 71% of guardians were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine in February 2021.12 The present study repeated the survey in the same demographic to determine whether guardian’s willingness to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine had changed in China since the policy allowing the emergency vaccination of 3–17-year-olds was announced. We further investigated the attitudes of guardians toward receiving the COVID-19 vaccine booster and the coadministration of other vaccines both for themselves and their children. Chinese adults were allowed to receive a booster dose. The COVID-19 booster was administered on priority to high-risk groups, such as staff working at ports and border regions and the elderly, and gradually, the scope was expanded to vaccinate the remaining population.13 Thus, our primary objective was to compare guardian willingness to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine before and after China introduced its child vaccination policy. Our secondary objectives were to investigate guardian willingness toward getting themselves and their children vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine booster; toward the coadministration of the COVID-19 and influenza vaccines for themselves; and toward the coadministration of the COVID-19 vaccine with other children’s vaccines not included in the standard child immunization program for their children. These additional vaccines are voluntary but must be paid for by the child’s guardian.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study on the guardians of children in China. We created a questionnaire based on the 3Cs (confidence, complacency, and convenience) theory of vaccine hesitancy.8 Twenty-three questions were designed and included in our questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire collected demographic and sociological information, including the role of guardian, age, education, occupation and annual income, as well as the child’s age, gender and other characteristics. The second part of the questionnaire collected the respondents’ willingness to let their children receive the COVID-19 vaccine. First, we asked the guardians whether they were the decision-maker in their homes regarding their children receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. For the guardians who replied positively, we asked whether they were willing to administer the COVID-19 vaccine to their child and the reasons for their response. The third part of the questionnaire collected the respondents’ willingness to administer the COVID-19 vaccine along with other children’s regular vaccines to their child, to receive the COVID-19 and influenza vaccines themselves, and to administer the COVID-19 vaccine booster to their child and receive it themselves.

The questionnaire was designed by the researchers and produced by the “Questionnaire Star” website (https://www.wjx.cn/). The questionnaire settings were adjusted to ensure data quality and answer effectiveness. First, each user could only fill in the questionnaire once. Once the user submits their response, it cannot be changed. Second, we clearly marked the different types of questions as single-choice, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions. For the open-ended questions, we placed certain restrictions on the responses, e.g., the guardian’s age can only be ≥18 years, to avoid users filling in mistakes. Third, we included some logical questions. For example, the guardian’s willingness to vaccinate their child was investigated only for those guardians who could make the decision regarding the child’s vaccination; guardians who could not take such decisions in the family skipped such questions. Fourth, all questions in the questionnaire had to be answered before submitting. Fifth, the total time to fill the questionnaire was limited to 3‒5 minutes. We removed questionnaires that were submitted beyond this time limit. Finally, we eliminated the questionnaires in which the open-ended questions were filled with obviously wrong answers.

Study population

The “Xiao Dou Miao” (XDM) app is used by parents of children aged 0–6. It has 30 million registered users from 31 provinces of mainland China and autonomous regions and municipalities. Therefore, the users of this app represented this study’s target population. The self-administered questionnaire was distributed by the XDM app, a mobile application that allows guardians to make inquiries and communicate on topics such as children’s vaccination and parenting. Guardians with access to this app responded to the survey from September 15 to 8 October 2021. Only guardians with children aged <6 years were included.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Chi-square testing was used to compare differences between different groups. Factors influencing attitudes toward vaccination were studied by binary logistic regression. A univariate logistic regression model was first applied and the statistically significant variables were further analyzed with a multivariate logistic regression model. All statistical tests were two-sided and p < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.0.2).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China (IPB-2020-15).

Results

Study sample characteristics

In total, 9424 guardians were included. Among the participants, 7,048 (74.79%) were mothers, 2,059 (21.85%) were fathers and 317 were other guardians, such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, and so on (3.36%). Parents aged 30‒39 years comprised the majority (57.05%). Furthermore, 2703 (28.69%) people were undergraduates or above. The family income per capita (CNY) of 6038 (64.07%) people was less than 100,000. A total of 3388 (35.95%) were housewives and 563 (5.97%) were healthcare workers. Among the guardians, 8196 (86.97%) had received the COVID-19 vaccine and 7915 (83.99%) could decide whether to vaccinate their children (these guardians were responsible for making such decisions). We found that 86.68% of the guardians were willing to have their children vaccinated. Willingness was slightly higher among fathers (88.25%) than among mothers (85.96%). There was a positive correlation between the respondents’ age and their willingness to their children (older guardians were more willing). Guardians with higher education and income had low willingness to vaccinate their children. With regards to occupations, willingness of guardians to vaccinate their children was higher among service workers (90.19%) and healthcare workers (89.40%). The willingness of guardians to vaccinate children aged ≥3 years (90.17%) and children without disease (87.02%) was high. The willingness of guardians who had received the COVID-19 vaccine themselves was high (88.41%). The details of each group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of guardians and their willingness to vaccinate their children with COVID-19 vaccine

| Variables | Guardians No. (%) | Guardians (who can decide whether the children is vaccinated) No. (%) | Guardians willing to vaccinate their children No. (%) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 9424(100%) | 7915(83.99%) | 6861(86.68%) | ||

| Guardians | |||||

| Mother | 7048(74.79%) | 5946(84.36%) | 5111(85.96%) | 16.12 | <0.001 |

| Father | 2059(21.85%) | 1745(84.75%) | 1540(88.25%) | ||

| Others | 317(3.36%) | 224(70.66%) | 210(93.75%) | ||

| Age | |||||

| 18–29 | 2505(26.58%) | 2026(80.88%) | 1704(84.11%) | 44.91 | <0.001 |

| 30–39 | 5376(57.05%) | 4580(85.19%) | 3954(86.33%) | ||

| 40–49 | 1224(12.99%) | 1082(88.40%) | 988(91.31%) | ||

| ≥50 | 319(3.38%) | 227(71.16%) | 215(94.71%) | ||

| Education | |||||

| Secondary education/secondary vocational education and below | 2055(21.81%) | 1683(81.90%) | 1518(90.20%) | 81.38 | <0.001 |

| Higher vocational education | 2395(25.41%) | 2032(84.84%) | 1813(89.22%) | ||

| College students | 2271(24.10%) | 1953(86.00%) | 1695(86.79%) | ||

| Undergraduates | 2414(25.62%) | 2010(83.26%) | 1650(82.09%) | ||

| Postgraduate education and above | 289(3.07%) | 237(82.01%) | 185(78.06%) | ||

| Family income per capita (CNY) | |||||

| ≤100,000 | 6038(64.07%) | 5013(83.02%) | 4420(88.17%) | 28.47 | <0.001 |

| 100,000–200,000 | 2455(26.05%) | 2098(85.46%) | 1774(84.56%) | ||

| 200,000–300,000 | 573(6.08%) | 491(85.69%) | 412 (83.91%) | ||

| ≥300,000 | 358(3.80%) | 313(87.43%) | 255(81.47%) | ||

| Occupation | |||||

| Housewives | 3388(35.95%) | 2853(84.21%) | 2462(86.30%) | 34.58 | <0.001 |

| Service workers | 1093(11.60%) | 917(83.90%) | 827(90.19%) | ||

| Healthcare workers | 563(5.97%) | 481(85.44%) | 430(89.40%) | ||

| Education workers | 637(6.76%) | 541(84.93%) | 446(82.44%) | ||

| Public officer | 1056(11.21%) | 877(83.05%) | 728(83.01%) | ||

| Laborers | 902(9.57%) | 756(83.81%) | 670(88.62%) | ||

| Others | 1785(18.94%) | 1490(83.47%) | 1298(87.11%) | ||

| Gender of children | |||||

| Boys | 5021(53.28%) | 4219(84.03%) | 3677(87.15%) | 1.73 | 0.18 |

| Girls | 4403(46.72%) | 3696(83.94%) | 3184(86.15%) | ||

| Age of children | |||||

| <3 | 4817(51.11%) | 3855(80.03%) | 3200(83.01%) | 87.9 | <0.001 |

| ≥3 | 4607(48.89%) | 4060(88.13%) | 3661(90.17%) | ||

| Underlying disease in children | |||||

| No | 8668(91.98%) | 7287(84.07%) | 6341(87.02%) | 8.9 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 756(8.02%) | 628(83.07%) | 520(82.80%) | ||

| Guardian vaccinated COVID-19 vaccine | |||||

| Yes | 8196(86.97%) | 7031(85.79%) | 6216(88.41%) | 162.27 | <0.001 |

| No | 1228(13.03%) | 884(71.99%) | 645(72.96%) |

Notes: χ2 was used to compare only willingness to vaccinate children. Guardians willing to vaccinate their children: the survey was conducted only for guardians who can decide to vaccinate their children in the family.

Factors influencing and reasons for guardians’ willingness to vaccinate their children

If China’s national policy allows children under 6 years to be vaccinated against COVID-19 in the future and the children meet the vaccination requirements, 86.68% of the guardians were willing to vaccinate their children and 13.32% of the guardians were uncertain or unwilling to vaccinate their children. For most guardians, the main reasons to vaccinate their children were concerns about their children being infected with COVID-19 (70.55%), belief that the COVID-19 vaccine can prevent infection or greatly reduce disease severity after infection (64.16%), belief in the publicity and advocacy of the government (44.69%), and belief in vaccine safety (41.97%). The main reasons for guardians being unwilling or uncertain to vaccinate their children were due to safety (10.37%); waiting to see whether children of other families are vaccinated (6.61%); concerns about vaccine effectiveness (2.75%); and inconveniences, such as living far from the vaccination site, queuing, and other competing demands on their time (1.12%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reasons for the guardians’ willingness, unwillingness, or uncertainty to vaccinate their children.

This was a multiple-choice question. Blue represents the reason why guardians were willing to vaccinate their children; red represents the reason why guardians were unwilling or uncertain to vaccinate their children.

Logistic regression was used to investigate the factors affecting guardians’ willingness. The results showed that guardians aged 40–49 years (vs. those aged 18–29 years, OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.19–2.00), guardians aged ≥50 years (vs. those aged 18–29 years, OR = 2.37, 95% CI: 1.29–4.35), healthcare workers (vs. those with other occupations, OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.17–2.31), and guardians with children aged ≥3 years (vs. guardians with children aged <3 years, OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.30–1.73) were more willing to vaccinate their children. Factors associated with guardians’ unwillingness to vaccinate their children were college education (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 0 .75, 95% CI: 0.60–0.92), undergraduate-level education (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 0 .52, 95% CI: 0.41–0.65), postgraduate education or above (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.28–0.58), having children with an underlying disease (vs. without an underlying disease, OR = 0 .70, 95% CI: 0.56–0.88), and not being vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine (vs. already being vaccinated, OR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.36–0.56) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Influencing factors on the willingness of guardians to vaccinate their children with COVID-19 vaccine

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| Variables |

OR |

95%CI |

p-value |

OR |

95%CI |

p-value |

| Guardians | / | |||||

| Mother | 1.32 | 1.14-1.51 | <0.001 | |||

| Father | ||||||

| Others | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 | 1.37 | 1.25-1.51 | <0.001 | Ref | ||

| 30–39 | 1.09 | 0.93-1.27 | 0.31 | |||

| 40–49 | 1.54 | 1.19-2.00 | <0.01 | |||

| ≥50 | 2.37 | 1.29-4.35 | <0.01 | |||

| Education | ||||||

| Secondary education/secondary vocational education and below | 0.78 | 0.74-0.83 | <0.001 | Ref | ||

| Higher vocational education | 0.90 | 0.72-1.11 | 0.32 | |||

| College students | 0.75 | 0.60-0.92 | <0.01 | |||

| Undergraduates | 0.52 | 0.41-0.65 | <0.001 | |||

| Postgraduate education and above | 0.40 | 0.28-0.58 | <0.001 | |||

| Family income per capita (CNY) | / | |||||

| ≤100,000 | 0.82 | 0.76-0.89 | <0.001 | |||

| 100,000–200,000 | ||||||

| 200,000–300,000 | ||||||

| ≥300,000 | ||||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Housewives | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | 0.23 | 1.07 | 0.87-1.30 | 0.53 |

| Service workers | 1.25 | 0.95-1.63 | 0.11 | |||

| Healthcare workers | 1.65 | 1.17-2.31 | <0.01 | |||

| Education workers | 0.96 | 0.72-1.27 | 0.76 | |||

| Public officer | 0.94 | 0.74-1.21 | 0.65 | |||

| Laborers | 1.04 | 0.78-1.37 | 0.81 | |||

| Others | Ref | |||||

| Gender of children | / | |||||

| Boys | 0.92 | 0.81-1.04 | 0.19 | |||

| Girls | ||||||

| Age of children | ||||||

| <3 | 1.88 | 1.64-2.15 | <0.001 | Ref | ||

| ≥3 | 1.50 | 1.30-1.73 | <0.001 | |||

| Underlying disease in children | ||||||

| No | 0.72 | 0.58-0.89 | 0.003 | Ref | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.56-0.88 | <0.01 | |||

| Guardian vaccinated COVID-19 vaccine | ||||||

| Yes | 0.35 | 0.30-0.42 | <0.001 | Ref | ||

| No | 0.43 | 0.36-0.56 | <0.001 | |||

Notes: OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Changes in willingness in the first and second surveys

In February 2021, we conducted our first survey on the guardians registered on the XDM app. Among the 12,872 respondents, 9122 were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine (70.87%). Our second survey was conducted 6 months later with respondents from the same platform. The second survey found that 6861 of the 7915 respondents were willing to vaccinate their children (86.68%), which was 16% higher than the first study (Table 1). The willingness of housewives, healthcare workers, those with higher vocational education, those with a family income per capita of ≥300,000 had all increased by approximately 20% (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of guardians’ willingness toward COVID-19 vaccination in the first survey and the second survey.

Willingness toward vaccination, coadministration with other vaccines, and receiving a COVID-19 vaccine booster

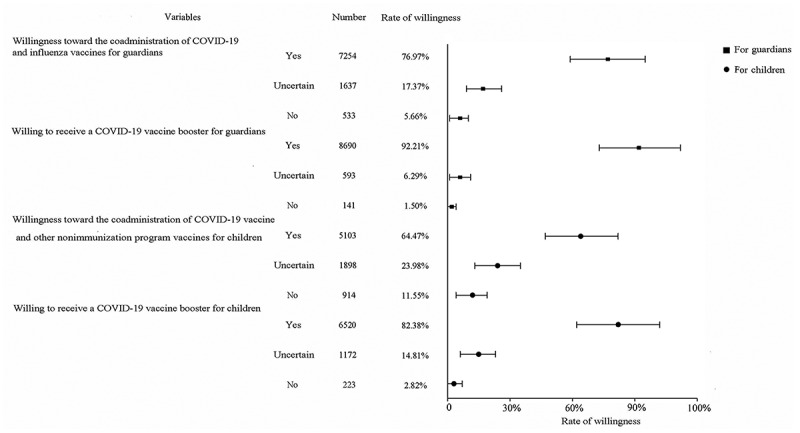

Among all guardians, 7254 (76.97%) were willing, 1637 (17.37%) were uncertain, and 533 (5.66%) were unwilling toward the coadministration of influenza vaccine with the COVID-19 vaccine (Figure 3). Fathers (vs. mother, OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.22–1.58), guardians already being vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine (vs. not being vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine, OR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.45–1.88), and guardians already being vaccinated with the influenza vaccine (vs. not being vaccinated with the influenza vaccine, OR = 2.29, 95% CI: 1.94–2.69) were more willing to coadministered (Table 3). The main reasons for being willing to receive coadministered vaccines were to avoid infection with other diseases and to allow the detection of nucleic acids due to symptoms similar to COVID-19 (59.24%), to save time and simplify the process (45.27%), and belief in government advocacy (36.40%). The main reason for uncertainty or unwillingness to receive coadministered vaccines was concerns about vaccine effectiveness (17.19%) (Table S1).

Figure 3.

Willingness and unwillingness toward the coadministration of COVID-19 vaccine with other vaccines for themselves and their children.

Table 3.

Influencing factors on the willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster, and to coadministrate with influenza vaccines and a COVID-19 booster for guardians

| Willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster |

Willingness to coadministrate with influenza vaccines and a COVID-19 booster |

|||||

| Multivariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| |

OR |

95%CI |

p-value |

OR |

95%CI |

p-value |

| Guardians | ||||||

| Mother | Ref | |||||

| Father | / | 1.39 | 1.22-1.58 | <0.001 | ||

| Others | 1.30 | 0.97-1.75 | 0.08 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 | Ref | |||||

| 30–39 | 1.38 | 1.16-1.64 | <0.001 | |||

| 40–49 | 1.39 | 1.05-1.84 | 0.02 | / | ||

| ≥50 | 1.05 | 0.67-1.65 | 0.83 | |||

| Education | ||||||

| Secondary education/secondary vocational education and below | Ref | |||||

| Higher vocational education | 1.39 | 1.13-1.73 | <0.01 | |||

| College students | 1.72 | 1.37-2.16 | <0.001 | / | ||

| Undergraduates | 1.32 | 1.06-1.64 | 0.01 | |||

| Postgraduate education and above | 1.15 | 0.72-1.81 | 0.55 | |||

| Guardian vaccinated COVID-19 vaccine | ||||||

| Yes | 4.23 | 3.57-5.02 | <0.001 | 1.65 | 1.45-1.88 | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Guardian vaccinated influenza vaccine from August 2020 to May 2021. | ||||||

| Yes | 1.38 | 1.07-1.77 | 0.01 | 2.29 | 1.94-2.69 | <0.001 |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

Notes: OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Of the guardians, 8690 (92.21%) were willing, 593 (6.29%) were uncertain, and 141 (1.50%) were unwilling to receive the COVID-19 vaccine booster (Figure 3). Age 30–39 years (vs. 18–29, OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.16–1.64), 40–49 years (vs. 18–29, OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.05–1.84), higher vocational education (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.13–1.73), college education (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.37–2.16), undergraduate-level education (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.06–1.64), guardians who already received the COVID-19 vaccine (vs. not being vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine, OR = 4.23, 95% CI: 3.57–5.02), and guardians already being vaccinated for influenza (vs. not being vaccinated with the influenza vaccine, OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.07–1.77) were more willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster (Table 3).

In total, 5103 (64.47%) guardians were willing, 1898 (23.98%) were uncertain, and 914 (11.55%) were unwilling toward the coadministration of other children’s nonimmunization program vaccines with the COVID-19 vaccine for their children (Figure 3). Fathers (vs. mother, OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.29–1.71) were more willing for their children to receive coadministered vaccines. The main reasons for being willing toward the coadministration for their children were to avoid infection with other diseases and to allow the detection of nucleic acids due to symptoms similar to COVID-19(62.08%), to save time and to simplify the process (34.71%), and belief in government advocacy (25.79%) (Table 4). The main reasons for uncertainty or unwillingness toward the coadministration were concerns about vaccine safety (27.42%), concern that the child was too young (19.43%), concerns about vaccine effectiveness (13.10%), and a desire to wait and see whether others vaccinate their children (10.73%) (Table S1).

Table 4.

Influencing factors on the willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster, and to coadministrate with non-immunization program vaccines and a COVID-19 booster for children

| Willingness to receive a COVID-19 booster |

Willingness to coadministrate with non-immunization program vaccines and a COVID-19 booster |

|||||

| Multivariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

| |

OR |

95%CI |

p-value |

OR |

95%CI |

p-value |

| Guardians | ||||||

| Mother | Ref | |||||

| Father | 1.48 | 1.29-1.71 | <0.001 | |||

| Others | / | 1.29 | 0.91-1.3 | 0.15 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Secondary education/secondary vocational education and below | Ref | |||||

| Higher vocational education | 0.97 | 0.82-1.16 | 0.76 | |||

| College students | 0.93 | 0.77-1.11 | 0.41 | |||

| Undergraduates | 0.71 | 0.59-0.86 | <0.001 | / | ||

| Postgraduate education and above | 0.53 | 0.38-0.75 | <0.001 | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Housewives | 0.73 | 0.57-0.93 | 0.01 | |||

| Service workers | 0.77 | 0.61-0.97 | 0.02 | |||

| Healthcare workers | 0.88 | 0.67-1.16 | 0.37 | / | ||

| Education workers | 1.35 | 0.95-1.90 | 0.09 | |||

| Public officer | 0.77 | 0.58-1.07 | 0.12 | |||

| Laborers | 0.81 | 0.61-1.06 | 0.13 | |||

| Others | Ref | |||||

| Year of children | ||||||

| <3 | Ref | |||||

| ≥3 | 1.46 | 1.29-1.64 | <0.001 | / | ||

Notes: OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Further, 6520 (82.38%) were willing, 1172 (14.81%) were uncertain, and 223 (2.82%) were unwilling to vaccinate their child with a COVID-19 vaccine booster (Figure 3). Undergraduate-level education (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.59–0.86), postgraduate education or above (vs. secondary education/secondary vocational education and below, OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.38–0.75), housewives (vs. those with other occupations, OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57–0.93), and service workers (vs. those with other occupations, OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61–0.97) were unwilling to administer the COVID-19 vaccine booster to their children. Guardians with children aged 3 years old or above (vs. aged under 3 years old, OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.29–1.64) were more willing to vaccinate their child with a COVID-19 vaccine booster (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we found that 86.68% of the guardians were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine. Guardians aged ≥40 years, healthcare workers, and those with children aged ≥3 years were more willing to vaccinate their children. Approximately 77% of the guardians were willing toward the coadministration of COVID-19 and influenza vaccines. Approximately 64% of the guardians were willing to coadminister other nonimmunization program vaccines with the COVID-19 vaccine to their children. If necessary, 92% of the guardians were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster and 82% were willing to vaccinate their children with a COVID-19 vaccine booster.

With the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of COVID-19 in children is rising and some severe cases and deaths have occurred.14,15 Anyone infected with the virus becomes a source of infection. Moreover, children are a clustered high-risk group. Hence, from the perspective of infectious source control, the management and protection of children are vital. Vaccination for children should also be considered a necessity if herd immunity is to be established. Alongside the global effort to ensure the vaccination of adults, some countries have also approved the emergency vaccination of minors. A clinical trial demonstrated that the Sinopharm vaccine is safe and well-tolerated at all established dose levels in subjects aged 3–17 years.16 Following vaccination, a stronger, more effective immune response against COVID-19 can be induced. However, parents of children aged <6 years are still hesitant about vaccinating their children. Our previous survey of guardians of children aged <6 years showed that 70.87% of the guardians were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine.12 Approximately 6 months later, after China had approved the emergency vaccination of minors aged 3–17 years, we resurveyed this population to investigate the changes in guardians’ willingness and determine the reasons behind vaccine hesitancy. This will enable policymakers and healthcare providers to optimize strategies to encourage vaccination compliance. This is the first follow-up study in China of the attitudes of guardians of 0–6-year-old children toward the COVID-19 vaccination of children. 6861 (86.68%) were willing to vaccinate their children.

A Saudi study surveyed 333 guardians, among which 53.7% of the guardians were willing, whereas 27% were unwilling to vaccinate their children.17 Among those who were unwilling, 95% gave a lack of information and evidence (for vaccine safety and efficacy) as their primary reason.17 A cross-sectional survey of pediatric caregivers found that, before they had received the vaccine themselves, 64.5% of adults were willing to vaccinate their children with COVID-19 vaccine. However, after receiving the vaccine themselves, the willingness decreased to 59.7%.18 In our study, the willingness of guardians to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine was 86.68%. In addition to the increase in the overall willingness of guardians to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine, there was also an increase in willingness in all of the subgroups in this study. A possible factor for this may be that, since the first survey, there has also been an increase in the number of people vaccinated. Only 9.6% of the guardians to our first survey had been vaccinated compared with 87% of those in our second survey. Having received the vaccination themselves may have increased the guardians’ willingness to vaccinate their children also. In addition, China has approved the emergency use of the COVID-19 vaccine for minors aged 3–17 years. Government propaganda and media information on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine may also have increased willingness.

Our surveys from both time points found a correlation between older age and greater willingness of guardians to vaccinate their children (p <0 .01). Further, guardians with high education and high income had low willingness to vaccinate their children. In China, people with high education usually have higher income. We think that these guardians may take the initiative to search for some vaccine information. With deeper understanding of knowledge on the effectiveness and side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, guardians were more cautious about vaccination especially for children. Respondents aged ≥40 years, healthcare workers, and guardians with children aged ≥3 years were more willing to vaccinate their children. Guardians with a higher level of education, guardians of children with underlying diseases, and guardians not vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine were less willing to vaccinate their children. So far, research suggests that the rate of adverse reactions to the COVID-19 vaccine in children is low.16 Government publicity has played a very important role in encouraging vaccination. More than half of the guardians believed that the vaccine can prevent infection or reduce the severity of postinfection disease. If the vaccination of children aged <6 years is approved in the future, education should continue to be provided to reduce noncompliance and eliminate the concerns of guardians.

Further objectives of this study were to investigate the willingness of guardians to allow the coadministration of other vaccines with the COVID-19 vaccine in both themselves and their children and their willingness to receive and vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine booster. Coadministration refers to the simultaneous vaccination of more than one vaccine in different parts. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus was found to be particularly high.17,18 The spread of coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A, especially influenza A H1N1, would result in the disease worsening, making pandemic prevention and control challenging.19 Therefore, we investigated whether respondents were willing to receive the COVID-19 and influenza vaccines at the same time. Around 84% of the guardians had not previously been vaccinated against influenza. In China, the influenza vaccine is offered free of charge in some provinces and cities. For example, in Beijing, the elderly who own the city’s resident identity certificate or social security card and are over the age of 60, all primary and secondary school students in school, and healthcare workers can be vaccinated against influenza free of charge. However, there are many others in which patients must pay for influenza vaccination. 77% of our respondents indicated that they were willing toward the coadministration of influenza vaccine. The most common reasons given for willingness (60%) were the belief that the coadministration could prevent influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 infection and that it would help to avoid detection of nucleic acids due to symptoms similar to COVID-19. The main reasons given by those unwilling to covaccinate were concerns about safety and effectiveness. Some respondents had herd mentality and indicated that they would consider coadministration only when they had seen others do it. Some felt that the pandemic was under control and additional protective measures, such as vaccine coadministration, were therefore unnecessary. Pregnant and breastfeeding respondents also expressed reluctance to vaccine coadministration.

Coadministration of vaccines in children can save parents time, effort, and expense and improve the efficiency of vaccination workers. More importantly, it can minimize the impact of new outbreaks on immunization services, improve vaccination coverage and timeliness, and provide social benefits. At present, the immunization program for children is free in China, which is a legal vaccination. Vaccines not included in this immunization program must be paid for. Children vaccinated with vaccines not included in this immunization program can receive broader protection. Therefore, if the future national policy allows children aged <6 years to be vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccine together with the other vaccines not included in the immunization program, whether the children’s parents are willing to vaccinate their children together.20 Our study found that about 65% of the guardians were willing toward their children being coadministered with nonimmunization program vaccines. This was lower than the rate of guardians’ willingness to receive co-administered vaccines themselves. Further, 24% of the guardians were uncertain and 12% were unwilling toward coadministration. The main reason given were concerns about the safety and effectiveness of coadministration and that the children were too young. Some also expressed concern about the high cost of nonimmunization program vaccines.

Our study had some limitations. First, the survey was conducted via an online questionnaire, which prevents effective random sampling. Therefore, this study was not representative of the whole population in China. However, there is still value in the analyses we have performed because we were comparing attitudes before and after the introduction of a new vaccination policy. So, even if the sample used have a generally positive bias, the differences between the data from the two timepoints are still valid as measures of the effect of the independent variable. Second, although the first and second surveys were conducted on the same platform and the stability of the platform population is good, privacy protection prevented following up individual respondents to map changes of attitudes in individuals. Finally, because these were self-administered questionnaires, there will be some information deviation.

Conclusion

This is the first follow-up study on the willingness of guardians to vaccinate their children aged <6 years with the COVID-19 vaccine. The two surveys belong to a dynamic population cohort. With the permission of national policies, >87% of the guardians were willing to vaccinate their children with the COVID-19 vaccine. We also investigated the willingness of the guardians to vaccinate themselves and their children with a COVID-19 vaccine booster. About 77% of the guardians were willing toward the coadministration of influenza and COVID-19 vaccines, and 64% were willing toward the coadministration of other children’s nonimmunization program vaccines with the COVID-19 vaccine. If necessary, 92% of the guardians were willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccine booster and 82% were willing to vaccinate their children with a COVID-19 vaccine booster. We hope that this research may facilitate the formulation of successful strategies for the implementation of COVID-19 vaccinations, covaccinations, and COVID-19 booster vaccinations, particularly in children aged <6 years and their guardians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the “XDM” app for helping us distribute the questionnaire.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the discipline construction funds of Population Medicine from Peking Union Medical College [No.WH10022021145]; Guilin talent mini-highland scientific research project for COVID-19 prevention and control (Municipal Committee Talent Office of Guilin City [2020] No. 3-05); COVID-19: Improve the safety and pharmacovigilance level of vaccines including COVID-19 vaccine (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation: INV-006373).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2049169.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. COVID-19 vaccines. [accessed 2022 Mar 12]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines

- 2.Zheng Y-J, Wang X-C, Feng L-Z, Xie Z-D, Jiang Y, Lu G, Li X-W, Jiang R-M, Deng J-K, Liu M, et al. Expert consensus on COVID-19 vaccination in children. World J Pediatr. 2021;17(5):449–9. doi: 10.1007/s12519-021-00465-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization, 10 vaccines granted Emergency Use Listing (EUL) by WHO. [accessed 2022 Mar 12]. https://covid19.trackvaccines.org/agency/who/

- 4.The People's Republic of China . People aged 3 to 17 can use the COVID-19 vaccine urgently. 2021 Jun 12 [accessed 2021 Jun 12]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-06/12/content_5617310.htm

- 5.World Health Organization. 12~17 year old COVID-19 vaccination is in an orderly way. 2021. Aug 14 [accessed 2021 Aug 12]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-08/14/content_5631259.htm

- 6.Beijing network. More than 1.5 million people aged 3-11 have been vaccinated with Xinguan vaccine in Beijing. 2022. Jan 22 [accessed 2022 Jan 12]. https://t.ynet.cn/baijia/32095545.html

- 7.Maldonado YA, O’-Leary ST, Banerjee R, Campbell JD, Caserta MT, Gerber JS, Kourtis AP, Lynfield R, Munoz FM, Nolt D, et al. COVID-19 vaccines in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruggiero KM, Wong J, Sweeney CF, Avola A, Auger A, Macaluso M, Reidy P.. Parents’ intentions to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35(5):509–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He K, Mack WJ, Neely M, Lewis L, Anand V. Parental perspectives on immunizations: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood vaccine hesitancy. J Community Health. 2021;47:39–52. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhodes ME, Sundstrom B, Ritter E, McKeever BW, McKeever R. Preparing for a COVID-19 vaccine: a mixed methods study of vaccine hesitant parents. J Health Commun. 2020;25(10):831–37. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2021.1871986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Zhang T, Qi W, Zhang X, Jia M, Leng Z, et al. COVID-19 vaccination in Chinese children: a cross-sectional study on the cognition, psychological anxiety state and the willingness toward vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1949950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The People's Republic of China.What is the trend of multi-point spread of the epidemic? How to play vaccine booster injection? 2021 Oct 24 [accessed 2022 Mar 12]. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-10/24/content_5644685.htm

- 14.Dufort EM, Koumans EH, Chow EJ, Rosenthal EM, Muse A, Rowlands J, Barranco MA, Maxted AM, Rosenberg ES, Easton D, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):347–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1607–08. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Yang Y, Gao GF, Tan W, Wu G, Xu M, Lou Z, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated COVID-19 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV, in people younger than 18 years: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:39–51. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00462-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altulaihi BA, Alaboodi T, Alharbi KG, Alajmi MS, Alkanhal H, Alshehri A. Perception of parents towards COVID-19 vaccine for children in Saudi population. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18342. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldman RD, Krupik D, Ali S, Mater A, Hall JE, Bone JN, Thompson GC, Yen K, Griffiths MA, Klein A, et al. Caregiver willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 after adult vaccine approval. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10224. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao L, Deng W, Qi F, Lv Q, Song Z, Liu J, Gao H, Wei Q, Yu P, Xu Y, et al. Sequential infection with H1N1 and SARS-CoV-2 aggravated COVID-19 pathogenesis in a mammalian model, and co-vaccination as an effective method of prevention of COVID-19 and influenza. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2021;6(1):200. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The People's Republic of China. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress . Vaccine administration law of the People’s Republic of China. Law Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.