ABSTRACT

Application of atoxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavusto soils is the most successful aflatoxin biological control approach. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacies of native non-aflatoxin producing (atoxigenic) strains as a biocontrol agent in peanut field in China. The competitive atoxigenic A. flavus strains (JS4, SI1and SXN) isolated from different crops, in China were used for field evaluation. The strains applied during the growing season (June – October, 2016) in the field at rate of 25 kg inoculum/hectare. The colonization of these biocontrol agents has been investigated and the population of A. flavus communities in soil were determined. The incidences of toxin producing (toxigenic) A. flavus strains and aflatoxin contamination in peanuts were also determined. Treated plots produced significant reductions in the incidence of toxigenic isolates of A. flavus in soil. However, the total fungal densities were not significantly different (p > 0.05) after treatments. Large percentage of aflatoxin reductions, ranging from 82.8% (SXN) up to 87.2% (JS4) were recorded in treated plots. Generally, the results suggest that the strategy can be used to control aflatoxin contamination and continuous evaluation should be done.

KEYWORDS: peanut, Atoxigenic Aspergillus flavusstrains, toxigenic Aspergillus flavusstrains, aflatoxins, biocontrol

1. Introduction

Members of the Aspergillus section Flavi fungal species (Aspergillus flavus and A.parasiticus) are known to infect important food crops (Frisvad et al. 2006). Peanut is one of the most vulnerable host crops to A. flavus invasion and subsequent aflatoxin (AF) contamination throughout its value chain (Barros et al. 2005). A. flavus populations can be subdivided into different groups based on sclerotia size (L-strain with >400 μm in diameter and S-strain <400 μm) (Abbas et al. 2005). Some S-strains produce both AFBs (AFB1, AFB2) and AFGs (AFG1, AFG2), whereas others produce only AFBs depending on their geographic origin (Cotty and Cardwell 1999). Other isolates with abundant small sclerotia (diameter <400 µm) classified as strain SBG (Cotty and Cardwell 1999). Within the A. flavus population some strains may produce different ranges of AF, called toxigenic, the rest may not produce at all (called atoxigenic) (Donner et al. 2009; B. W. Horn and Dorner 1999). Most of the atoxigenic isolates of A. flavus belongs to L-strains. AF are generally carcinogenic (Liu and Wu 2010) immune suppressor (Okoth 2016; Mupunga et al. 2017) as well as cause growth impairments in children (Gong et al. 2002, 2003). AFB1 is the most potent and frequently occurring (Kew 2013). Regulatory agencies limit the maximum tolerable limit of AF. The upper limit for AFB1 in peanuts is 2 ng/g and 4 ng/g for total AF (B1+ B2+ G1+ G2) in the European Union, where as China has a tolerance of 20 ng/g for total AF (FAO 2004), similar limit is adopted by the United States (Wu et al. 2016).

Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), is an iodole tetramic acid, which was originally discovered in peanuts as a fungal metabolite (Holzapfel 1968). A. flavus strains are major producers of CPA, and naturally, they are found to occur as a co-contaminant with AF resulting in important economic losses (Bamba and Sumbali 2005; Astoreca et al. 2014).

The world peanut production totals approximately 42.24 million metric tons in the 2016/2017 growing season, and China was the world’s largest producer contributing to 17 million metric tons (USDA 2017). The five provinces of China such as Guangdong Shandong, Henan, Hebei, and Jiangsu contribute 70% of the country’s production (Yao 2004). Most of the peanut production is located in the South and Southeast regions, where there is relatively higher humidity and temperature favourable for A. flavus growth and AF contamination at pre-harvest stage (Cotty and Jaime-Garcia 2007). Reports have revealed higher levels of AF contamination in crops from the southern part of China (like Guangdong province) (Gao et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2016). One strategy that has been developed for reducing preharvest AF contamination of crops is biological control, which is achieved by applying naturally occurring competitive native atoxigenic strains of A. flavus to the soil (Horn and Dorner 2009). Atoxigenic A. flavus strains interfere with the proliferation of indigenous toxigenic strains (Chang et al. 2012; Pitt et al. 2015; Alaniz Zanon et al. 2016). Also, soil inoculation with atoxigenic strains has a carry-over effect and may protect peanuts from contamination during storage (Dorner and Cole 2002).

Several atoxigenic strains of A. flavus have been patented, registered, and commercialised. In USA, from 2004 to 2008 two atoxigenic A. flavus strains such as NRRL 21882 (active component of Afla-guard ®) and AF36 (NRRL 18543) were registered and used (Abbas et al. 2011) widely. In addition, a strain K49 (NRRL 30797) has been patented by USDA (King et al. 2011). Several field experiments on the efficacy of potential atoxigenic A. flavus have been reported in other parts of the world such as USA, Argentina, Nigeria, Australia, and Thailand (Abbas et al. 2006; Pitt & Hocking 2006; J Atehnkeng et al. 2008; Pitt et al. 2015; Alaniz Zanon et al. 2016). In doing so, significant levels of aflatoxin reduction (43% – 98%) have been achieved.

Interest in the distribution of A. flavus species across China has also increased because of increasing suggestions to utilise isolates of atoxigenic strains A. flavus to reduce aflatoxin contamination (Yin et al. 2009; Tran-Dinh et al. 2014; Wei et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2015) Recently, the distribution of A. flavus in different agro-ecological zones has been reported (Zhang et al. 2017; Mamo et al. 2018). Molecular characteristics of potential atoxigenic A. flavus strains have been reported elsewhere (Jiang et al. 2009; Yin et al. 2009).

Very recently, the efficacy test of atoxigenic A. flavus strains against higher aflatoxin producer strains co-inoculated at the equal amount in the soil has been done by group of researchers in China (Yan et al. 2021). In this study, significant aflatoxin reduction (84.96–99.33%) has been achieved. However, no cases were reported before on utilising them in the field condition against the naturally existing multiple fungal strains. Moreover, no cases were reported in China about the carry-on effects of field-applied atoxigenic A. flavus on stored peanuts.

Our earlier work has identified 24 potential biocontrol A. flavus strains and characterised that all of them were atoxigenic, non-CPA production and lack important aflatoxin biosynthetic genes (from 5 to 17) (Mamo et al. 2018). In the current study, three candidate atoxigenic strains (JS4, SI and SXN) were selected for the field test and they are lack more than 10 AF- biosynthetic genes and two important CPA-biosynthetic genes. Therefore, the efficacy of those three native atoxigenic A. flavus strains was evaluated to reduce AF contamination in peanuts under field conditions at the Guangdong province, the southern part of China and their carry-on effects at storage conditions.

2. Material and method

2.1. Strain selection

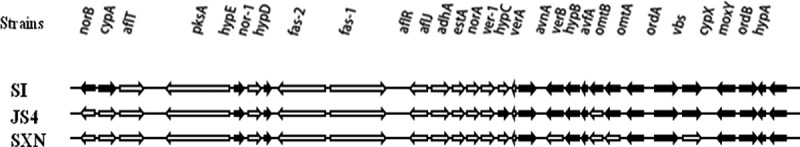

The competitive strains used were A. flavus strains JS4, SI and SXN. These strains are naturally occurring isolate obtained from crops of China (Table 1). These strains were characterised by Mamoet al.,(2018) and shown to produce neither aflatoxins nor cyclopiazonic acid. The PCR assay revealed that they lost more than 10 aflatoxin biosynthetic cluster genes (Figure 1,2) and none of them did not amplified two functional genes in CPA biosynthesis pathway.

Table 1.

Information about the competitive atoxigenic A. flavus strains used in the field

| Strain code | Location | Source | Sclerotia size a | Radial growth rate (cm/day) b |

Deletion pattern c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI | Sichuan | Rice | L | 0.67 | j |

| JS4 | Jiangsu | Peanut | L | 0.64 | l |

| SXN | Shaanxi | Peanut | L | 0.62 | r |

aSclerotia size: L: sclerotia diameter >400 μm, S: sclerotia diameter <400 μm

bRadial growth rate (cm/day determined on dilute 1 × 104 CFU/ml) PDA, 3–7 days incubation in darkness at 30 °C. C Deletion pattern

Figure 1.

Aflatoxin biosynthesis pathway genes absent patterns of potential biocontrol agents.

Figure 2.

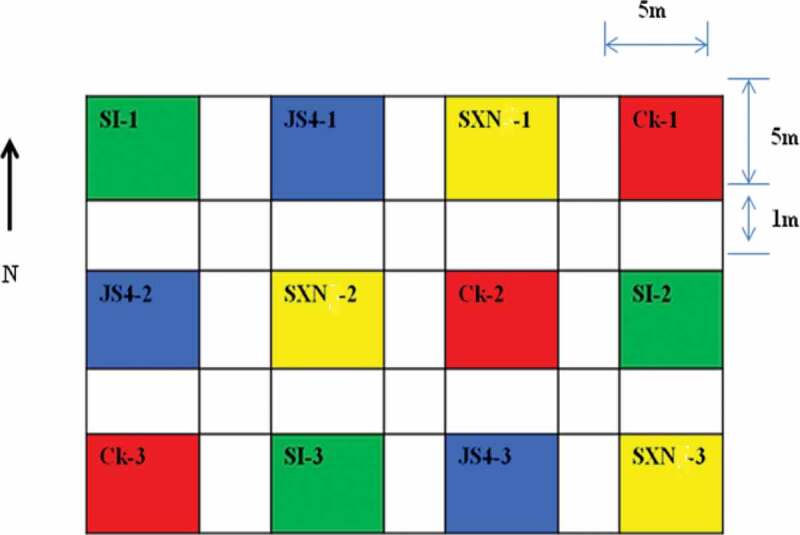

Sketch of the plots for field experiment in Zhanjiang.

2.2. Inoculum preparation

The A. flavus strain inocula were produced by solid-state fermentation on autoclaved wheat according to (Alaniz Zanon et al. 2016) with little modifications. Briefly, wheat seed (500 g) was soaked in water overnight, drained, placed in a 5-litre flask, and autoclaved. Distilled water was added to attain 35–40% moisture content in the wheat. Starter cultures of A. flavus were grown on PDA in 9-cm Petri dishes at 28 °C for 5 days under continuous darkness. The autoclaved wheat was inoculated with 1 ml of a conidial suspension (107/ml), and incubated for 4 days at 30 ° C, the flasks were shaken daily to avoid clump production. At the end of the incubation period, the substrate was dried in a forced-air draft oven at 40°C over night. The dried wheat was then crushed. The viable count (cfu/g) of A. flavus in the substrate was determined by homogenising 10 g in 90 ml of peptone water 0.1% (wt/v). This mixture was then shaken and diluted to final concentrations of 10−2 and 10−3. From each dilution, 0.1 ml was spread in triplicate on Dichloran Rose Bengal Chloramphenicol (DRBC) modified with 3% NaCl (Horn and Dorner, 1999). The Petri dishes were incubated in darkness for 5–7 days at 30°C. All inoculated wheat contained 108cfu A. flavus/g.

2.3. Field assays

The field assays were done in a commercial field with the previous history of peanut cultivation, located within the peanut-growing region of Guangdong province, Zhanjiang, China. The experiments were established as completely randomised design; the plot consisted of 5 m × 5 m divided into 12 subplots, with a buffer area of 1 m between plots. The peanut cultivar (Zhanyou 75) was planted in rows at 70 cm distance. The planting dates were 24 June 2016. The inoculum was added to fields manually after mixing 62.5 g of pre-inoculated and crushed wheat with 1 kg of sand to attain uniform distribution so that the rate were set at 25 kg inoculum/ha. Inoculation was done on 24 September 2016, 1 month before harvesting (24 October 2016). Subplots comprised controls and treatments as follows: (1) uninoculated control; Ck (2) plots inoculated with atoxigenic A. flavus strains JS4, SI and SXN.

2.4. Harvest and storage of peanut

Manually harvested peanuts have been dried outside for 7 days and stored in a room in polyethylene bags from October 2016 up to January 2017 for 4 consecutive months. The storage conditions such as relative humidity and temperature were recorded four times a day (6-h interval) and average figures were calculated. At every 30 days of storage time, 3 kg of peanuts were taken to the laboratory of the institute of food science and technology for fungal invasion and aflatoxin B1 analysis.

2.5. -Soil mycobiota analysis

Soil fungal population analysis was done according to (Alaniz Zanon et al. 2016) with slight modification. Briefly, ten soil samples were taken in two diagonal transects extending from opposing corners in each subplot 1 month before planting and immediately after 15 days of planting and during maturation of the pods prior to digging to determine the soil mycobiota and Aspergillus section Flavi (A. flavus/A. parasiticus) populations. Each soil sample (approximately 100 g) was a pool from 5 subsamples taken with a trowel from the top 5 cm of soil where peanuts would be or were forming. Sub-samples of each sample were combined in a paper bag and air-dried for 1–2 days at 25–30°C. Samples were thoroughly mixed and passed through a testing sieve (2 mm mesh size).

2.6. Soil fungal isolation and identification

From each soil sample 10 g was diluted with 90 ml of peptone water 0.1% (w/v). This mixture was shaken for 20 min and decimally diluted. A 0.1 ml aliquot of each dilution per sample was spread on the surface of solid media: Dichloran Glycerol 18% (DG18). The plates were incubated in darkness for 5–7 days at 30°C. The results were expressed as colony forming units per gram (cfu/g) of soil. Fungal colonies that resembled Aspergillus section Flavi were sub cultured on malt extract agar medium (MEA) for further identification according to Klich (2002).

2.7. Soil toxigenic profile

A. flavus isolates were screened for aflatoxin production on coconut cream agar. A modified version of the medium described by (Degola et al. 2011) was used for its efficacy as a diagnostic medium for aflatoxin production: a commercial coconut milk, available from local markets was diluted to 40% (v/v) with distilled water and 15 g agar powder was added, sterilised by autoclaving. Strains inoculated at the centre, after incubation at 30°C for 3 days, media dishes were placed upside down and a drop (0.2 ml) of 25% ammonia solution was placed into the lid of each culture dish to release ammonium vapour (Saito and Machida 1999).Colour development (pink pigmentation) upon contact with ammonium vapour was indicative for aflatoxin synthesis. Consequently, absence of colour development was indicative for absence of aflatoxin development. The plates were scored as positive or negative and isolates were grouped as either toxigenic or atoxigenic (Fani et al. 2014).

2.8. Mycobiota analysis from peanut samples

Harvesting and drying were done in October 2016, according to the common practices by the farmers in the area. After drying, four trials of mycobiota analysis were done at each month interval (October 2016 – February 2017). From each subplot, approximately 3 kg of kernels were used. This sample was mixed thoroughly, and 60 kernels (3 replicates) were selected for fungal infection determination. The remaining sample was ground to obtain a subsample of 25 g (3 replicates) for aflatoxin analysis. Peanut kernels from each sub plot were surface disinfected for 1 min in 1% sodium hypochlorite solution, rinsed three times in sterile distilled water and transferred to Petri dishes containing Dichloran Rose Bengal Chloramphenicol agar (DRBC) modified with 3% NaCl (Alaniz Zanon et al. 2016). Plates were incubated at 25°C for 7 days. The incidence of toxigenic isolates of A. flavus/A. parasiticus in peanuts was determined by testing all the isolates for toxigenicity as described above for soil samples.

The aflatoxin analysis was performed using the kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Romer Labs, Getzersdorf, Austria). Briefly described as follows, 25 g of peanuts were ground and put into a 150-ml flask and mixed with 100 ml of the extraction solvent, 84:16 (Acetonitrile: Water, v/v). The mixture was shaken for 60 min at a high speed at 180 rpm in a shaker incubator and filtered with an analytical filter paper. ROMER Aflatoxin clean up column was used for cleaning; 2 ml of the extracted supernatant mixed with 23 ml of phosphate buffer Saline (PBS) modified with 1% tween 20 and passed through the solid-phase extraction column (SPE); on a vacuum manifold at a flow rate of 1–3 drops per second. After column loading, the immune affinity SPE column was washed with 10 ml of PBS before being eluted with 0.5 × 2 ml and 0.5 × 2 ml of water and methanol respectively. The elute was filtered with 0.22 micro litre filter and filled into HPLC vials for HPLC analysis. One hundred micro litres of the extract were injected into the HPLC apparatus (Agilent 2600, Series, Agilent Technology, Germany) with post-column photochemical reactor for enhanced detection (HUAAN, MAGNECH, Beijing, China) with a full loop injection system. The analytical column was an Agilent STC-C1812/250 × 4.6 mm. The column was thermo stated at 30°C. The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of water: methanol (70:30, v/v) eluted at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/ min. The fluorometric detector was set at wavelengths, ex = 365 nm, em = 435 nm. Aflatoxins B1, were measured by comparing peak areas with a calibration curves obtained with aflatoxin standard solutions (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The detection limit was 1ppb.

3. Statistical analysis

Completely randomised designs with three to four replicates were used in all experiments. Means separation and comparison were made by Tukey-Kramer HSD test at a probability level of p = 0.05. ANOVA was performed with JMP statistical software (version 13; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Mean differences in aflatoxin levels of peanut (percent difference between inoculated plot and untreated plots) were calculated as [1 – (total aflatoxin content in peanut from inoculated plots/total aflatoxin content in peanut from untreated plot)] × 100.

4. Results

The density of total mycobiota before the application of the bioproducts in the field was homogeneous across all soil samples, with an average count 1 × 104cfu/g. The inoculum levels of native Aspergillus section Flavi before treatment was also homogenous and similar among plots (1 × 102 cfu/g of soil). A. flavus counts were uniform (5 × 102cfu/g) as well.

After treatment, counts of total mycobiota and Aspergillus section Flavi were not significantly different compared with the control plot, both after 15 and 30 days of inoculation (Table 2.). However, a significantly (p < 0.05) higher incidence of (40.8%) of toxigenic A. flavus strains was observed in control compared to biocontrol treated plots (Table 2.). Generally, the incidence of toxigenic A. flavus decreased in all biocontrol treated plots after 30 days of incubation. All treated plots showed lower incidence of toxigenic A. flavus after 30 days of inoculation than 15 days of inoculation. Numerically, JS4 treated plot showed a slightly lower incidence of toxigenic strains in comparison to other treatments both after 15 and 30 days of inoculation (Table 2.).

Table 2.

Total mycobiota, Aspergillus section Flavi, A. flavus and incidence of toxigenic A. flavus from soil samples before and after treatments

| TR | Before treatments |

15 days after treatment |

30 days after treatment |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMB (cfu/g)a |

ASF (cfu/g)a |

Af (cfu/g) a | AF+(%) b | TMB (cfu/g) a |

ASF (cfu/g)a | Af (cfu/g) a |

AF+ (%) b | TMB (cfu/g)a |

ASF (cfu/g)a |

Af (cfu/g) a |

AF+ (%) b | |

| CK | 1 × 104 | 1 × 103 | 5 × 102 | 70 | 1.3 × 104b | 1.5x103a | 620 c | 28.4a | 1.6x104a | 1.7x103a | 250.3b | 40.8a |

| JS4 | - | - | - | - | 2.6× 105ab | 2.7x105a | 2.3x105ab | 4.9b | 2.3x105a | 2.1x105a | 2.x104a | 4.7b |

| SI | - | - | - | - | 1.2× 105ab | 7x104a | 7x104ab | 5.5b | 1.7x105a | 1.0x105a | 1.0x104a | 6.1b |

| SXN | - | - | - | - | 1.4× 105ab | 7.6x104a | 8.3x104ab | 12.3ab | 1.1x105a | 9.6x104a | 1.5x104a | 4.8b |

All the data represent the average values of three replicates.

aThe counts are expressed as colonies forming units per gram of soil (cfu/g).

bThese data are expressed as the percentage of the toxigenic strains (AF+(%)).

Abbreviations: TR-refers treatments, CK- control, ASF- Aspergillus section Flavi, TMB-total mycobiota, Af- A. flavus strains

Means in a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different (Tukey-Kramer HSD test, p > 0.05).

At harvesting, there were no significance differences (p> 0.05) both on the peanut infection rate (PIR) and incidence of toxigenic A. flavus among all the biocontrol treated plots. Peanut infection rate generally was below 10% in all plots. Across storage time, the incidence of peanut kernels infected with A. flavus was higher in treated plots than in the control. PIR shows increment across the storage time from October to January (Table 3). In January, the relatively highest infection rate ranged from 40.0% to 46.1% were seen on the peanuts collected from biocontrol treated plots. However, these values were not significantly different (p> 0.05) (Table 3.). The maximum PIR (35%) by the natural A. flavus inoculum was seen in January followed by December (24.4%) (Table 3.). In October and November relatively smaller PIR (10% and 16.1%) were recorded by the natural A. flavus. Comparing to control plots, significant reductions in incidence of toxigenic isolates were observed in peanut kernels from biocontrol treated plots across the course of storage time. Stored peanut kernels treated with JS4 show reduced incidence of toxigenic A. flavus in December (9.2%) and January (11.8%). On the contrary, the highest 89.9% and 90.7% toxigenic A. flavus strains were isolated in peanuts collected from untreated plots during the above storage times, respectively (Table 3.).

Table 3.

Infection of peanut kernels by total A. flavus, percentage of toxigenic A. flavus and aflatoxin contamination during the course of storage time

| Treatments | October-2016 |

November-2016 |

December-2016 |

January-2017 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIR(%)a | AF+(%)b | PIR(%)a | AF+(%)b | PIR(%)a | AF+(%)b | AFB1(ppb)c | PIR(%)a | AF+(%)b | AFB1(ppb)c | |

| Control | 10.0bd | 77.8a | 16.1b | 62.5a | 24.4b | 89.9a | 27.3a | 35.0a | 90.7a | 4.2 |

| JS4 | 23.9ab | 13.3b | 28.9a | 13.4b | 37.4ab | 9.2 c | 3.5 c | 41.6a | 11.8b | ND |

| SI | 23.3ab | 6.5b | 32.2a | 19.3b | 38.3a | 12.2 c | 4.6b | 40.0a | 12.0b | ND |

| SNX1 | 27.2a | 10.1b | 30.0a | 7.2b | 37.8ab | 19.1b | 4.7b | 46.1a | 21.8b | ND |

All the data represent the average values of three replicates.

aPeanut infection rate (PIR) is expressed as the percentage of peanut kernels infected with A. flavus.

bAF+, these data are expressed as the percentage of the toxigenic strains.

cAflatoxin levels (AFB1) are expressed as parts per billion (ppb) (ND = not detected; < 1 ppb).

Within a column, values not sharing a common letter are significantly different (Tukey-Kramer HSD test, p < 0:05).

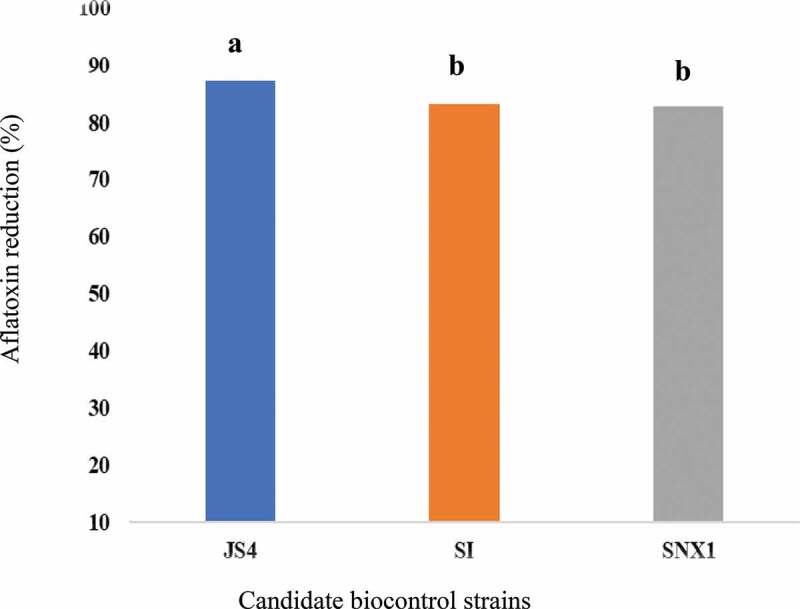

No AFB1 was detected at harvesting time and the first 2 months of storage. It was detected in peanuts in December and January. Significantly (p < 0.005) higher AFB1 content (27.3 ppb) was detected in peanut kernels from the untreated plot than biocontrol treated plots at December (Table 3). Significantly lower levels (p < 0.05) AFB1 content ranged from 3.5 to 4.7 ppb was detected in peanut kernels from treated plots (Table 3). JS4 treated plot showed the least (3.5 ppb) at this time. In comparison to the uninoculated control plot, large average AFB1reduction, ranged from 82.8% (SNX) up to 87.2% (JS4) were recorded (Figure 3). During the last month of storage; in January, no AFB1 was detected from all the treatments. However, in average 4.2 ppb AFB1 was observed in the control plot (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Aflatoxin reduction in peanut kernels harvested.

5. Discussions

This study provided the first report on the efficacy of A. flavus biocontrol strains applied in the peanut field in one of the major peanut-producing regions of China (Guangdong province), Zhejiang. In this field experiment, the native inoculum level (50 cfu/g) and the incidence of toxigenic isolates of A. flavus (>50%) were uniform among plots (Average 5 × 102 cfu/g). Similarly, the inoculum level of native Aspergillus section Flavi in the soil prior to planting was also homogeneous among plots (1 × 102 cfu/g). Among members of Aspergillus section flavi, A. flavus was the dominant species (93%). These data are consistent with the previous study done in China (Zhang et al. 2017). However, it is lower compared with another study in Argentina (Alaniz et al. 2013).

In the soil samples, no significant changes were observed in the total fungal colony, Aspergillus section flavi as well as A. flavus counts both after 15 and 30 days of inoculation (Table 2). This implies that, there was no major change on the total fungal population of the field because of the addition of atoxigenic A. flavus to the field. Similar results observed in USA (Dorner 2002). Analyses of soils taken prior to harvest showed that the treatments resulted in an increase in the incidence on atoxigenic A. flavus in treated plots. The mean A. flavus population density in soils before treatment was 5 × 102 cfu/g, of which 70% of isolates tested were toxigenic. The mean A. flavus population densities in plots treated with atoxigenic strains at harvest were (JS4, 2 × 10 4 cfu/g), (SI, 1 × 10 4 cfu/g), (SNX, 1 × 10 4 cfu/g) but only 4.0%, 6.1%, and 4.8% of isolates tested were toxigenic for each treatments, respectively. Therefore, application of biocontrol agents had the desired effect of changing the composition of the A. flavus soil population to greatly favour the atoxigenic strain.

At harvesting time, peanut infection rate (PIR) by total A. flavus population from both treated and untreated plots was lower (<10%) and no detectable aflatoxin observed. The infection rate increased across the storage time for all plots. Relatively, higher peanut infection was recorded in December and January (Table 3.). The infection rate observed at these times (December and January) were not significantly (p> 0.05) different between untreated and treated plots. These data suggest that generally, treatment of soil with atoxigenic strains did not increase total infection of peanuts by A. flavus, but rather, it resulted in the preferential invasion of peanuts by atoxigenic strains compared with native toxigenic strain (Dorner and Cole 2002).

At these storage times, the highest incidence (89.9%, 90.7%) of toxigenic A. flavus were observed in kernels from the control plot. However, significantly lower incidence of toxigenic (9.2% – 21.8%) A. flavus was recorded in kernels from the atoxigenic treated plots. Significant displacement by competitive atoxigenic A. flavus strains was occurred. For instance, the strain JS4 showed the highest displacements (from 88.2% to 90.8%) of toxigenic A. flavus at the above storage times (Table 3.). This implies that the strain JS4 had profound competitive performance in the field.

Detectable aflatoxin contamination was not observed at pre-harvest and during the first 2 months of storage time. Delayed aflatoxin contamination is possible because of climatic conditions at pod maturations and natural defence by the peanut kernel. Fungal growth, host invasion and as well as aflatoxin contamination occur when there is optimum environmental condition (Wu et al. 2016). Despite, the mean environmental temperature and humidity registered were 30°C and 79%, respectively. the last period of peanut growth (Figure 4). However, there was continuous rain (266.7 mm) for more than 20 days during this time according to World Weather and Climate Information, data from nearest weather station: Haikou, China (129.8 KM). Furthermore, the natural defence mechanisms of the peanut must be minimised after fungal invasion. Hence, certain periods of time are required for aflatoxin contamination to occur on surface of kernels following penetrating the pod (Diao et al. 2014).

Figure 4.

Natural storage conditions of harvested peanuts.

After 2 months of storage AFB1 was detected from kernels. Significantly higher AFB1 concentration (27.3 ppb) was obtained at December in kernels from untreated plots; this value is by far higher than the national aflatoxin limits (15 ppb) of standards (Wu et al. 2016). However, samples from atoxigenic strain treated plots showed relatively lower (3.5–4.6 ppb) AFB1 content at this storage time. This implies that atoxigenic strains reduces AFB1 from 82.9% to 87.2%. Similarly, atoxigenic A. flavus; JS4 strain demonstrates the highest (87.2%) aflatoxin reduction on storage. Furthermore, except kernels from control plots, no detectable aflatoxin was recorded in January (Table 3). This implies that all atoxigenic (JS4, SI, and SNX) A. flavus strains achieved 100% of aflatoxin reduction. However, minimised mean AFB1 (4.2 ppb) detected by the native toxigenic leads us as some external environmental factors are attributed to these data.

Overall peanut infection rate of A. flavus is 35%. Even though, the atoxigenic A. flavus in the control reached to 90.7%, aflatoxin contamination was not higher, this might be attributed to the environmental factors and moreover, the physiology of the crops. A study by Dorner et al. (2003) also revealed as aflatoxin contamination is not always directly correlated with the incidence of invasion by A. flavus. Drought, temperature and water stresses are among the environmental factors for aflatoxin contamination to occur (Craufurd et al. 2006). The humidity remains higher (>75%) while the average monthly temperature decreased from 28°C in October to 21°C in January (Figure 4). According to Paterson and Lima (2010, 2011), climate changes (temperature and rainfall) can influence host-pathogen dynamics so does the aflatoxin production. Similarly, the water activity (Aw) that may be reduced across storage time could also possibly affects aflatoxin production on kernels.

6. Conclusions

This study proved that field application of indigenous atoxigenic A. flavus can efficiently suppress populations of toxigenic strains in the soil and on peanut kernels via the competition and reduce aflatoxin contamination during peanut storage without increasing either the percentage of kernels infected by A. flavus in the field or the overall quantity of those fungi present in peanuts after storage. Generally, the competitive exclusion of toxigenic A. flavus via atoxigenic ones provides a new strategy for the management of aflatoxin contamination of peanuts and other crops.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the Laboratory of Quality and Biosafety at the Institute of Food Science and Technology at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for their comments and participation in discussions regarding this work.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFC1604502).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbas HK, Weaver MA, Zablotowicz RM, Horn BW, Shier WT.. 2005. Relationships between aflatoxin production and sclerotia formation among isolates of Aspergillus section Flavi from the Mississippi Delta. Eur J Plant Pathol. 112(3):283–287. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas HK, Zablotowicz RM, Bruns HA, Abel CA. 2006. Biocontrol of aflatoxin in corn by inoculation with non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolates. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 16:437–449. . [Google Scholar]

- Abbas HK, Zablotowicz RM, Horn BW, Phillips NA, Johnson BJ, Jin X, Abel CA. 2011. Comparison of major biocontrol strains of non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus for the reduction of aflatoxins and cyclopiazonic acid in maize. Food Addit Contam. 28(2):198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaniz Zanon MS, Barros GG, Chulze SN. 2016. Non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus as potential biocontrol agents to reduce aflatoxin contamination in peanuts harvested in Northern Argentina. Int J Food Microbiol. 231:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaniz ZMS, Chiotta ML, Giaj-Merlera G, Barros G, Chulze S. 2013. Evaluation of potential biocontrol agent for aflatoxin in Argentinean peanuts. J Food Microbiol. 162(3):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astoreca A, Vaamonde G, Dalcero A, Marin S, Ramos A. 2014. Abiotic factors and their interactions influence on the co-production of aflatoxin B1 and cyclopiazonic acid by Aspergillus flavus isolated from corn. Food Microbiol. 38:276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atehnkeng J, Ojiambo PS, Donner M, Ikotun T, Sikora RA, Cotty PJ, Bandyopadhyay R. 2008b. Distribution and toxigenicity of Aspergillus species isolated from maize kernels from three agro-ecological zones in Nigeria. Int J Food Microbiol. 122(1–2):74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atehnkeng J, Ojiambo PS, Ikotun T, Sikora RA, Cotty PJ, Bandyopadhyay R. 2008a. Evaluation of atoxigenic isolates of Aspergillus flavus as potential biocontrol agents for aflatoxin in maize. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 25:1264–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamba R, Sumbali G. 2005. Co-occurrence of aflatoxin B1 and cyclopiazonic acid in sour lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) during post-harvest pathogenesis by Aspergillus flavus. Mycopathologia. 159:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros G, Torres A, Chulze S. 2005. Aspergillus flavus population isolated from soil of Argentina’s peanut-growing region. Sclerotia production and toxigenic profile. J Sci Food Agric. 85(14):2349–2353. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PK, Abbas HK, Weaver MA, Ehrlich KC, Scharfenstein LL, Cotty PJ. 2012. Identification of genetic defects in the atoxigenic biocontrol strain Aspergillus flavus K49 reveals the presence of a competitive recombinant group in field populations. Int J Food Microbiol. 154(3):192–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotty PJ, Cardwell KF. 1999. Divergence of West African and North American Communities of Aspergillus Section Flavi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 65(5):2264–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotty PJ, Jaime-Garcia R. 2007. Influences of climate on aflatoxin producing fungi and aflatoxin contamination. Int J Food Microbiol. 119(1–2):109–115. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168160507003959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craufurd PQ, Prasad PVV, Waliyar F, Taheri A. 2006. Drought, pod yield, pre-harvest Aspergillus infection and aflatoxin contamination on peanut in Niger. F Crop Res. 98(1):20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Degola F, Berni E, Restivo FM. 2011. Laboratory tests for assessing efficacy of atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus strains as biocontrol agents. Int J Food Microbiol. 146(3):235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao E, Dong H, Hou H, Zhang Z, Ji N, Ma W. 2014. Factors influencing aflatoxin contamination in before and after harvest peanuts: a review. J Food Res. 4(1):148–154. http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/jfr/article/view/43819 [Google Scholar]

- Donner M, Atehnkeng J, Sikora RA, Bandyopadhyay R, Cotty PJ. 2009. Distribution of Aspergillus section Flavi in soils of maize fields in three agroecological zones of Nigeria. Soil Biol Biochem. 41(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner J, Cole R, Connick W, Daigle D, Mcguire M, Shasha B. 2003. Evaluation of biological control formulations to reduce aflatoxin contamination in peanuts. Biol Control. 26:318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Dorner JW, Cole RJ. 2002. Effect of application of nontoxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus on subsequent aflatoxin contamination of peanuts in storage. J Stored Prod Res. 38:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Dorner W 2002. Combined effects of biological control formulations, cultivars, and fungicides on preharvest colonization and aflatoxin contamination of peanuts by Aspergillus Species. 79–86.

- Fani SR, Moradi M, Probst C, Zamanizadeh HR, Mirabolfathy M, Haidukowski M, Logrieco AF. 2014. A critical evaluation of cultural methods for the identification of atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolates for aflatoxin mitigation in pistachio orchards of Iran. Eur J Plant Pathol. 140:631–642. . [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2004. Food and Agriculture Organization (2004) worldwide regulations for mycotoxins in food and feed in 2003. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 81. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- Frisvad JC, Thrane U, Samson RA, Pitt JI. 2006. Important mycotoxins and the fungi which produce them. In: Adv Exp Med Biol [Internet]. Vol. 571. [place unknown]; p. 3–31. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16408591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Liu Z, Yu J. 2007. Identification of Aspergillus section Flavi in maize in northeastern China. Mycopathologia. 164(2):91–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong YY, Cardwell K, Hounsa A, Egal S, Turner PC, Hall AJ, Wild CP. 2002. Dietary aflatoxin exposure and impaired growth in young children from Benin and Togo: cross sectional study. BMJ. 325(7354):20–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong YY, Egal S, Hounsa A, Turner PC, Hall AJ, Cardwell KF, Wild CP. 2003. Determinants of aflatoxin exposure in young children from Benin and Togo, West Africa: the critical role of weaning. Int J Epidemiol. 32(4):556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel CW. 1968. The isolation and structure of cyclopiazonic acid a toxic metabolite of Penicillium cyclopium Westling. Tetrahedron. 24(5):2101–2119. isi:A1968A641100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn BW, Dorner JW. 1999. Regional differences in production of aflatoxin B1 and cyclopiazonic acid by soil isolates of Aspergillus flavus along a transect within the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 65(4):1444–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn BW, Dorner JW. 2009. Effect of nontoxigenic Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus on aflatoxin contamination of wounded peanut seeds inoculated with agricultural soil containing natural fungal populations. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 19(3):249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Yan L, Ma Z. 2009. Molecular characterization of an atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus strain AF051. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 83:501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew MC. 2013. A atoxins as a cause of hepatocellular carcinoma. Reviews. 22(3):305–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King ED, Bassi AB, Ross JC, Druebbisch B. 2011. An industry perspective on the use of “atoxigenic” strains of Aspergillus flavus as biological control agents and the significance of cyclopiazonic acid. Toxin Rev [Internet]. 30(May):33–41. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3339596&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klich MA. 2002. Identification of common Aspergillus species. Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures; p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wu F. 2010. Global burden of aflatoxin-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: a risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 118(6):818–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamo FT, Shang B, Selvaraj JN, Wang Y, Liu Y. 2018. Isolation and characterization of Aspergillus flavus strains in China. J Microbiol. 56(2):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mupunga I, Mngqawa P, Katerere DR. 2017. Peanuts, aflatoxins and undernutrition in children in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients. 9(12):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoth S. 2016. Improving the evidence base on aflatoxin contamination and exposure in Africa. Wageningen: The Netherlands. https://www.cta.int/en/issue/. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson RRM, Lima N. 2010. How will climate change affect mycotoxins in food ? Food Res Int [Internet]. 43(7):1902–1914. 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson RRM, Lima N. 2011. Further mycotoxin effects from climate change. FRIN [Internet]. 44(9):2555–2566. 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.05.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt JI, Hocking AD. 2006. Mycotoxins in Australia: biocontrol of aflatoxin in peanuts. Mycopathologia. 162(3):233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt JI, Manthong C, Siriacha P, Chotechaunmanirat S, Markwell PJ. 2015. Studies on the biocontrol of aflatoxin in maize in Thailand. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 25(9):1070–1091. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2015.1028893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Machida S. 1999. A rapid identification method for aflatoxin-producing strains of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus by ammonia vapor. Mycoscience [Internet]. 40(2):205–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02464300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Dinh N, Pitt JI, Markwell PJ. 2014. Selection of nontoxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus for biocontrol of aflatoxins in maize in Thailand. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 3157:1–20. . [Google Scholar]

- USDA USD of A . 2017. World agricultural production.

- Wei D, Zhou L, Selvaraj JN, Zhang C, Xing F, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Liu Y. 2014. Molecular characterization of atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolates collected in China. J Microbiol. 52(7):559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Ding X, Li P, Du X, Zhou H, Bai Y, Zhang L. 2016. Aflatoxin contamination of peanuts at harvest in China from 2010 to 2013 and its relationship with climatic conditions. Food Control. 60:117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Song W, Chen Y, Kang Y, Lei Y, Huai D, Wang Z, Wang X, Liao B. 2021. Effect of non-aflatoxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus on aflatoxin contamination of pre-harvest peanuts in fields in China. Oil Crop Sci. 6(2):81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yao G 2004. Peanut production and utilization in the People’s Republic of China. Peanut in Local and Global Food Systems Series Report No. 4, USA (Georgia). [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Lou T, Yan L, Michailides T, Ma Z. 2009. Molecular characterization of toxigenic and atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolates, collected from peanut fields in China. J Appl Microbiol. 107(2009):1857–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Selvaraj JN, Yang Q, Liu Y. 2017. A survey of aflatoxin-producing Aspergillus sp. from peanut field soils in four agroecological zones of China. Toxins (Basel). 9(40):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Wei -D-D, Selvaraj JN, Shang B, Zhang C-S, Xing F-G, Zhao Y-J, Wang Y, Liu Y. 2015. A strain of Aspergillus flavus from China shows potential as a biocontrol agent for aflatoxin contamination. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 25(5):583–592. [Google Scholar]