Abstract

Background:

Social Emergency Medicine (Social EM) examines the intersection of emergency care and the social factors that influence health outcomes. In 2021, the SAEM consensus conference focused on Social EM and Population Health, with the goal of prioritizing research topics, creating collaborations, and advancing the field of Social EM.

Methods:

Organization of the conference began in 2019 within SAEM. Co-chairs were identified and a planning committee created the framework for the conference. Leaders for subgroups were identified, and subgroups performed literature reviews and identified additional stakeholders within EM and community organizations. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the conference format was modified.

Results:

Two hundred forty-six participants registered for the conference and participated in some capacity at three distinct online sessions. Research prioritization subgroups were: Group 1: ED screening and referral for social and access needs, Group 2: Structural Competency, and Group 3: Race, Racism, and Anti-racism. Thirty-two “Projects in Progress” were presented within 5 domains: Identity and Health: People and Places; Health Care Systems; Training and Education; Material Needs; and Individual and Structural Violence.

Conclusions:

Despite ongoing challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 SAEM consensus conference brought together hundreds of stakeholders to define research priorities and create collaborations to push the field forward.

Introduction

Social emergency medicine (Social EM) examines the intersection of emergency care and the social factors that influence health outcomes.1 Social EM acknowledges the role of emergency departments (EDs) as safety net providers and aims to incorporate social context into the structure and delivery of emergency care.2 These social factors can include social determinants of health (SDoH) - the conditions in which people live that are “shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources,”3 social risks - “specific adverse social conditions that are associated with poor health” such as food insecurity or housing instability, and social needs - “individual preferences and priorities regarding assistance.”4

While commonly referred to as a novel field, the underlying tenets of Social EM existed long before the term, given the pivotal role the ED has already played in public health.5 The term “Social Emergency Medicine” was coined and disseminated in 2007 by Harrison Alter and Barry Simon, the physician-researchers behind the creation of the Andy Levitt Center for Social Emergency Medicine.6 Ten years later, a small group of clinician-researcher thought leaders convened to discuss the advancement of their shared goals, the proceedings of which were later published in their entirety: Inventing Social Emergency Medicine.7 Concurrently, the field expanded through increased training, research, and the creation of fellowships, and Social EM Interest Groups emerged within the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM).

At the same time, evidence emerged demonstrating that social needs are risk factors for increased ED use and poor health outcomes.8–14 Thus, government, health systems, and public health organizations have become increasing interested in evaluating SDoH and social need.15 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services developed an health related social need (HRSN) screening tool for use in the Accountable Health Communities model,16 and there were several ongoing state experiments, such as proposals for incentivizing payments to address HRSN.17 Both the National Quality Forum and the American Medical Association were working on systems to identify and address SDoH in the Electronic Health Record.18,19

However, most of the federal initiatives were focused on SDoH screening and intervention in the primary care setting, with little discussion of the role of the ED. This is a critical gap because patients who seek care in the ED may have even greater social needs, given that they are more likely to experience chronic disease, rely on public insurance, and identify with minoritized racial and ethnic groups.20,21 Despite interest among ED providers in addressing SDoH and social needs, barriers inherent to the acute care environment result in missed opportunities to identify social needs and intervene.22,23 Given the lack of attention to SDoH, there was both an urgent need and an opportunity to build on the strong interest in Social EM to set a research agenda in order to advance the field. Our objective is to describe the process of organizing and executing the Social EM Consensus Conference.

Organization of the Conference

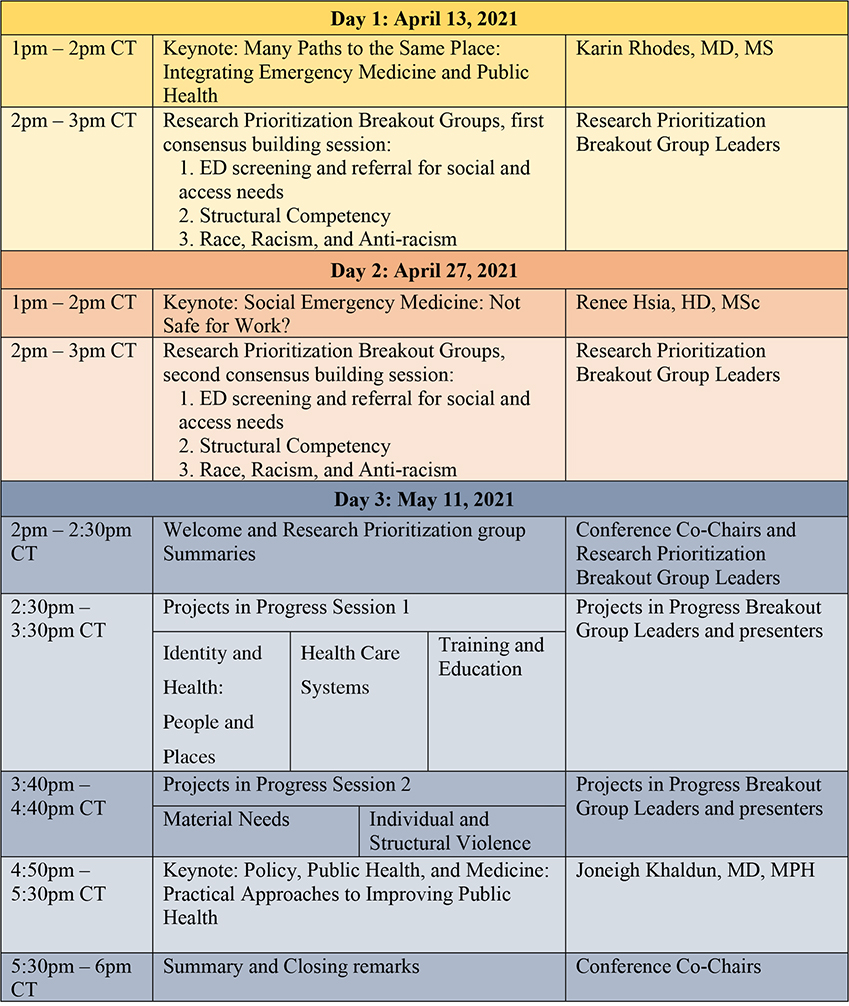

As momentum towards consensus conference planning began to coalesce in 2017–2018, the SAEM Social EM and Population Health Interest Group (SEMPH IG) recruited participants and organizers via meetings and listservs. At the 2019 SAEM National Conference SEMPH IG meeting, Co-Chairs were identified, and a Planning Committee formed. The timeline of meeting planning is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of planning activities from initial discussions through the conference. Green indicates stakeholder engagement; yellow indicates Research Prioritization activities; grey indicates Projects in Progress.

PiP = Projects in Progress; IG = Interest Groups;

In May 2019, immediately following the annual SAEM National Meeting, a survey was distributed via the SAEM listserv, the ACEP Social EM Interest Group list, Twitter, and via informal networks advertising the planning of the consensus conference (Google Forms, Google, Inc, Mountainview, CA, USA). Recipients were asked to sign up to be involved, and to indicate how they would like to participate (grant writing, organizing breakout sessions, analyzing conference proceedings, or general attendance). Supporting organizations are listed in Table 1. In 2019, an application for a consensus conference, submitted to SAEM by the SAEM SEMPH IG, was approved.

Table 1.

Organizations and sponsors supporting the application for an SEM Consensus Conference

| Organization |

|---|

| Department of Emergency Medicine – Massachusetts General Hospital (sponsor) |

| Department of Emergency Medicine – University of Massachusetts Medical School - Baystate (sponsor) |

| Department of Emergency Medicine – Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (sponsor) |

| Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science, University of Massachusetts Medical School - Baystate (sponsor) |

| Department of Emergency Medicine – Emory University School of Medicine (sponsor) |

| Office of Emergency Care Research, NIH (OECR) |

| Emergency Medicine Foundation (EMF) |

| American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) |

| Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network) (SIREN) |

| Levitt Center for Social Emergency Medicine |

| Western Journal of Emergency Medicine (WJEM) |

| Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) |

| Academy of Women in Academic Emergency Medicine (AWAEM, SAEM) |

| Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM, SAEM) |

| Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine (CORD) |

| Residents and Medical Students (RAMS, SAEM) |

| American Foundation for Firearm Injury Reduction in Medicine (AFFIRM) |

| SocialEMpact.com |

| FemInEM |

| RoshReview |

The goal of this consensus conference was to bring together researchers, educators, clinicians, and other stakeholders with an interest in SEMPH research in order to identify best practices, clarify knowledge gaps, prioritize research questions and set the research agenda for the continued development of Social EM. In particular, the aims were:

Aim 1: Research Prioritization: To assess the state of the science, clarify knowledge gaps, and set research priorities for the field of Social EM, so that collectively our research will improve the health of our communities, advance the field, and contribute to the development and implementation of best practices.

Aim 2: Collaboration: To bring together stakeholders so that we may more efficiently collaborate on research agendas, disseminate innovations, and address consensus-derived research priorities. By facilitating networking, we hope to create new research partnerships, enable fundable collaborations, and accelerate research in this area. This collaboration will also support faculty development for emergency medicine researchers, educators, trainees, and faculty.

Aim 1: Research Prioritization

In discussion of the structure of the conference, the planning committee identified three broad domains for research prioritization breakout sessions. The initial proposed conference had three breakout sessions focused on research on (1) screening and referral for social needs; (2) incorporating social EM into education and training; and (3) structural competence. In summer 2020, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and disproportionate COVID-19 mortality among Black and Latinx populations, the education and structural competence breakouts were merged, and a separate breakout session was organized around race, racism and anti-racism in EM. The final breakout groups were (1) ED screening and referral for social and access needs (2) Structural Competency and (3) Race, Racism, and Anti-racism. Within each group, members focused on: defining the current state of the research (synthesized prior to the conference by the leaders); assessing collaboratively the current research and knowledge gaps; and prioritizing, via consensus methods, the research goals for each domain. These three areas evolved with discussion and the final topics are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research Prioritization Domains, with descriptions and leaders. These domains were decided by the Planning Committee and leaders and members were recruited in 2019.

| Title | Description given to participants | Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1: ED screening and referral for social and access needs | EDs serve a disproportionate number of patients with health related social needs (HRSN) such as unstable housing, food insecurity and lack of transportation. Further, HRSN may contribute to increased rates of disease, delays in diagnosis and inadequate disease control, increased ED utilization and health care costs, and poor health outcomes. Although the primary function of an ED is the diagnosis and management of acute illness and injury, there is increased recognition that identifying and intervening on HRSN in the ED setting may have important value for the patient and the health care system. In this breakout session we examine three distinct, yet interconnected, aspects of HRSN screening and intervention in the ED. Using a consensus based approach that draws from an extensive literature review and expert assessment, we will identify research priorities related to following areas: (A) instruments used for screening of social and material needs in the ED, (B) implementation of social and material needs screening in the ED, and (C) interventions for patients with social and material needs in the ED. |

Callan Fockele, MD, MS Herbert Duber, MD, MPH Kelly Doran, MD, MHS Richelle Cooper, MD, MSHS |

| Group 2: Structural Competency | In the United States, the ED has historically cared for patients who are socially disenfranchised and face significant barriers to accessing quality and affordable health care. Recent scholarship suggests that health-seeking behaviors and dependence on ED services reflect historical and structural inequities—in healthcare and US society more broadly. Taking into account this longstanding and understudied role of the ED as a safety net, it is critical that we reframe our systems of care delivery, educational curricula, and metrics of evaluation to prepare the next generation of emergency physicians to understand, identify and respond to systemic causes of health inequities in ED clinical practice. This group builds on recently developed frameworks of “structural competency” and aims to operationalize them for ED researchers and educators. The goal of this group is to propose research and educational methodologies that critically examine and address the structural difficulties faced by patients (e.g., housing, immigration status, over-policing) and to develop strategies for delivering structurally competent care. |

Bisan Salhi, MD, PhD Amy Zeidan, MD |

| Group 3: Race, Racism, and Anti-racism | This group will discuss the current literature regarding race/racism and anti-racism in the context of EM and ED care. After a brief overview of the current literature, we will explore and discuss research priorities regarding studying and addressing racial and ethnic disparities, interventions to address implicit and explicit bias, and important next steps in the implementation of anti-racism work in EM. | Emily Cleveland-Manchanda, MD Anna Darby, MD, MPH Hannah Janeway, MD |

ED = Emergency Department; HRSN = Health related social needs; EM = Emergency Medicine

Leaders and a core of 8–12 members for each group were sought via SAEM committee and interest group listservs and the list of volunteers previously recruited. These groups began convening over a year before the conference. Each group concurrently conducted a literature search to map the evidence and synthesize the research regarding their domain. They then met monthly to discuss resultant themes and research questions, and brought this analysis to the conference over two sessions in April 2021 with the goal of achieving consensus on a research agenda. Each breakout group session was followed by surveys to meeting participants to assess and collate feedback on the research agenda, specifically on any research gaps that might have been missed by the core small group. The final findings from each Research Prioritization group will be presented separately.

Aim 2: Collaboration

To develop new networks of collaboration among Social EM investigators, we planned five “Projects in Progress” sessions to enable attendees to share short presentations of ongoing implementation work or research in progress, giving participants opportunities to hear about different projects and facilitating collaborations. We solicited presenters from diverse geographic locations and training levels prior to the conference, using the previously noted recruitment strategies. All those already registered for the conference were also encouraged to apply. A networking session, open to all attendees, was planned for after the “Projects in Progress” forum. The final topic areas for “Projects in Progress” breakout sessions are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Projects in Progress Breakout Groups

| Title | Description | Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| I. Identity and Health: People and Places | This session includes: • Race and Racism • Gender and Sexual Identity • Immigration • Language and Literacy • Neighborhoods and the Built Environment |

Breena Taira, MD, MPH Hannah Janeway, MD Molly E.W. Thiessen, MD |

| II. Health Care Systems | This session includes: • Access to Care • Frequent ED Use • Substance Use |

Shaw Natsui, MD, MPA Elizabeth Samuels, MD, MPH, MHS Hemal Kanzaria MD, MSHPM Mohsen Saidinejad, MD, MS, MBA |

| III. Training and Education | This session includes: • Training of clinicians and staff • Medical education • Novel/Alternate curricula |

Ayesha Khan, MD Adedamola Ogunniyi, MD Kian Preston-Suni, MD, MPH |

| IV. Material Needs | This session includes: • Education and Employment • Financial Insecurity • Food Insecurity • Housing Instability and Quality • Transportation |

Dennis Hsieh, MD, JD Austin Kilaru, MD, MSHP |

| V. Individual and Structural Violence | This session includes: • Violence • Firearm Injury • Incarceration • Human Trafficking • Legal Needs |

Harrison Alter, MD, MS Hanni Stoklosa, MD, MPH Shamsher Samra, MD, MPhil Natasha Thomas, MD |

ED = Emergency Department

To further strengthen networks for collaboration, organizers sought involvement of community groups – both local and national – that had goals that aligned with the conference. Specifically, leaders of research prioritization breakout sessions were asked to identify groups with expertise in related areas and ask those groups if a representative could be involved in drafting research priorities early in the process, after current literature was synthesized but before the actual conference. These groups were offered reimbursement for their time, particularly recognizing that work addressing social needs and risks is often underpaid. These groups were also invited to present their work at the “Projects in Progress” sessions. Participating groups are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Invited Community Groups

| Group, Location, Website | Mission Statement |

|---|---|

| Health Leads https://healthleadsusa.org/about-us/ | We partner with communities and health systems to address systemic causes of inequity and disease. We do this by removing barriers that keep people from identifying, accessing and choosing the resources everyone needs to be healthy. |

| Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network (SIREN) San Francisco, CA https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/ | Our mission is to improve health and health equity by advancing high quality research on health care sector strategies to improve social conditions. |

| Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) Washington, DC https://aspe.hhs.gov/about | ASPE advises the HHS on policy development in health, disability, human services, data, and science; and provides advice and analysis on economic policy. |

| American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) Health Equity Research/Policy & Partnerships/Programs https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-research/health-equity | The AAMC Center for Health Justice is committed to partnering with other organizations, community leaders, and community members to build true collaborations and an aligned agenda for health. |

| Beyond Flexner Alliance (BFA) Washington, DC https://www.beyondflexner.org/ |

The BFA is a national movement, focused on health equity and training health professionals as agents of more equitable health care. This movement takes us beyond centuries-old conventions in health professions education to train providers prepared to build a system that is not only better, but fairer.

The BFA aims to promote social mission in health professions education by networking learners, teachers, community leaders, health policy makers and their organizations to advance equity in education, research, service, policy, and practice.” |

| Women of Color Health Equity Collective Springfield, MA https://wochec.org/ | Our mission is to promote the resilience and empowerment of Women of Color to advance health and wellness by building community-capacity and advocating for just policies through evidence-based research and grassroots organizations. Core principles: Cultural Humility, Anti-Racism, Racial Equity, Social Justice, Reproductive Justice. |

Funding and awards

Three external submissions to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute were favorably scored but not funded; therefore, sponsorship was obtained from several academic EM Departments (Table 1). The planning committee created awards for students and residents to reward the impressive work being done, and to provide free registration to award winners. A call for applications was announced in December 2020, and awards were announced in March 2021. Sixty-three individuals applied for a medical student or resident award, and 35 received an award. Each award covered registration both for the consensus conference and for the annual meeting.

Conference Execution and Results

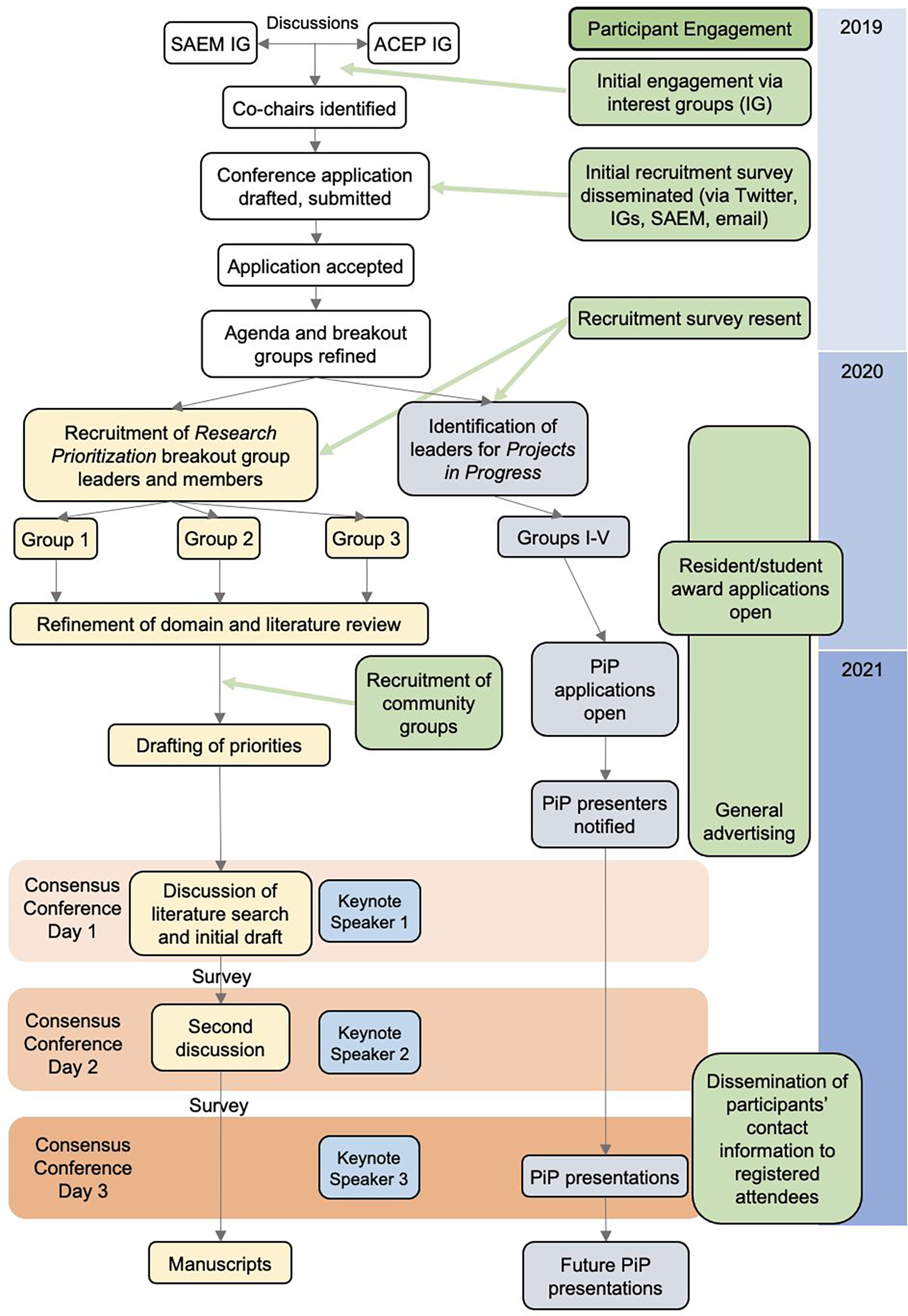

Initial requests for involvement in via survey in 2019 yielded 157 responses. Since the Consensus Conference has traditionally occurred on the day prior to the Annual Meeting, the research prioritization breakout sessions were planned as three concurrent one-hour morning sessions followed by networking lunch. Afternoon “Projects in Progress” were planned as two concurrent one-hour sessions followed by two more concurrent one-hour sessions, with post-conference networking to accelerate collaborations. Three keynote speakers (opening, lunch, and closing) were identified and recruited for their substantial contributions to the field of Social EM. In March of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic began. As a result of travel restrictions, the conference was adapted to a virtual format. Research prioritization breakout sessions occurred as two separate events in April, over two 2-hour blocks, and “Projects in Progress” were presented in May, without the in-person networking session. The final schedule is seen in Figure 2. Two hundred and forty-six participants registered for the conference, (128 [58%] faculty, 15 [7%] fellows, 39 [18%] medical students, and 38 [17%] residents), and over 170 came to each of the three sessions. Research prioritization breakout sessions in April were well-attended, with 12–40 participants in each session. Participants were asked self-report demographics (Table 5).

Figure 2.

Final agenda for the Consensus Conference

CT = Central Time

Table 5.

Participant demographics (collection of this information was voluntary)

| Participant Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Registered | 246 |

| Demographic Data Collected | 145 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 37.7 (sd 10) |

| Self-identified gender | |

| Woman | 95 (65.5%) |

| Man | 42 (30.0%) |

| Chose not to answer | 8 (5.6%) |

| Self-identified race | |

| African American or Black | 17 (11.7%) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 1 (1.0%) |

| Asian | 26 (17.9%) |

| White | 82 (56.6%) |

| Multiracial or other | 10 (6.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 11 (7.6%) |

| Hispanic or Latino (self-identified) | |

| No | 120 (82.8%) |

| Yes | 13 (9.0%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 (8.3%) |

| Level of training/role | |

| Medical Student | 22 (15.2%) |

| Resident or Fellow | 35 (24.1%) |

| Faculty physician | 80 (55.2%) |

| Community partner | 5 (3.5%) |

| Other (psychologist, health service researcher, government employee) | 4 (2.8%) |

On April 13, 2021, the conference commenced with a keynote lecture from Dr. Karin Rhodes, Chief Implementation Officer, Office of the Director, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Her talk was titled, “Many Paths to the Same Place, Integrating Emergency Medicine and Public Health” and she described her pathway to governmental service at the intersection of EM, public health, and health policy and her pioneering work on ED screening for social risks that laid the framework for Social EM. Following the keynote, participants then joined one of the three research prioritization breakout sessions (Screening and Referral, Structural Competency or Race, Racism, Anti-Racism), where group leaders presented a summary of their literature review and a preliminary analysis of research gaps and priorities.

Participants who attended a breakout group session during the first day of the conference (April 13th) were asked to provide feedback on the research gaps and priorities presented at the breakout session they attended using a web-based survey (Surveymonkey Inc, San Mateo, California, USA). Leaders then synthesized attendee input prior the second and final breakout session held on April 27, 2021. This second session was preceded by a keynote presentation from Dr. Renee Hsia, Professor of EM and Health Policy at the University of California San Francisco, entitled “Social Emergency Medicine: Not Safe for Work?” in which she shared personal narratives motivating her research and advocacy. During this second April session, leaders of each research subgroup presented an updated list of research priorities based on attendee input. After extensive discussion, attendees were asked to rank research priorities.

The “Projects in Progress” session occurred during a 4-hour session on May 11, 2021. A total of 52 applications to present were submitted, and 32 were chosen by domain leaders. Moderators, presenters, and attendees engaged in virtual chat within the 5 domains and presenters shared contact information in order to support continued dialogue and collaboration after the conference. The conference concluded with “Policy, Public Health, and Medicine: Practical Approaches to Improving Public Health,” a keynote by Dr. Joneigh Khaldun, the Chief Medical Executive and Chief Deputy Director for Health in the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Khaldun shared her impactful work as a public health leader during the COVID-19 pandemic, working to reduce disparities and improve equity in COVID-19 testing, treatment, and vaccinations in Michigan.

DISCUSSION

Although the consensus conference was organized and conducted at a time when ED providers were struggling with access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and increased risks to themselves due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of the field of Social EM only became more apparent with each passing day. The research summarized at the consensus conference, the research agendas created by the working groups, and specifically the final keynote speech by Dr. Khaldun addressed the intersection of health equity, racism, and the impact of COVID-19, and gave strategies to directly address the structural factors causing the health disparities that the year so painfully highlighted.

The conference plan was substantially impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, a pivot to a virtual format, and scheduling changes. In addition, stakeholder engagement via the virtual format was challenging. We sought at least two community stakeholders for each breakout session in order to ensure community voices were included in the research prioritization consensus discussions. While we were successful at having at least two community members in each research prioritization session group, future conferences should prioritize additional community involvement. At the conference, the planning committee worked to encourage an interactive format through live discussion and chat functions. Recognizing the limitations of networking on a virtual platform, organizers also shared presenters’ contact information for each “Projects in Progress” session in order to promote continued dialogue and future collaborations. Additionally, it is unclear what effects the COVID-19 pandemic had on registration and participation. The virtual format may have enabled participation (or intermittent participation) by people who would not have been able to come to an in-person event. However, the substantial stressors of the year – such as increased clinical demands, decreased childcare, personal losses, PPE shortages, and other emotional stressors – may have prevented the attendance of people who might have otherwise participated.

Other challenges included a lack of federal funding. Prior consensus conferences had been supported by mechanisms such as the National Institutes of Health R13. Despite favorable reviews and excellent scores, funding priorities shifted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the applications were not funded. However, the co-chairs were able to secure external funding from academic institutions as a means of supplementing conference expenses not covered by registration fees.

Additional challenges became apparent regarding the dual lift a consensus conference asks of research prioritization breakout leaders. Breakout leaders are often topic experts but may not be experts in consensus methodology. A protocolized plan from SAEM to standardize the consensus procedures would decrease the burden for consensus conference organizers. Given the positive response and strong attendee engagement, the 20 applicants who were unable to present their “Projects in Progress” were notified that they will be invited to present at future virtual presentations to be hosted by the SAEM SEMPH Interest Group. Ongoing work includes the development and maintenance of a collaboration platform for future Social EM-focused research networks, and the continued development of an active web platform for dissemination of social EM information and teaching resources.24

CONCLUSION

We convened a Consensus Conference that defined research priorities to advance the field of Social EM. Our conference successfully brought together stakeholders to disseminate innovations and best practices, and to discuss barriers. Future work should focus on developing strategies to sustain these collaborations and partnerships and to advance the science of improving population health and mitigating adverse social risk through emergency care.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Melissa McMillian for her many contributions to this conference. The authors would also like to acknowledge the substantial contributions of the entire planning committee.

Financial Support:

1. EMS is supported by a grant from AHRQ 1K08HS025701-01A1

2. MPL is supported by a grant from NHLBI/NIH K23HL143042-01A1

Footnotes

No authors report any conflicts of interest. EMS, ML, and MS-K have received grants for investigator-initiated research, listed above in Funding.

References

- 1.Shah R, Della Porta A, Leung S, et al. A Scoping Review of Current Social Emergency Medicine Research. West J Emerg Med. 2021. Oct 27;22(6):1360–1368. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.4.51518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malecha PW, Williams JH, Kunzler NM, Goldfrank LR, Alter HJ, Doran KM. Material Needs of Emergency Department Patients: A Systematic Review. Acad Emerg Med 2018;25:330–59. DOI: 10.1111/acem.13370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and Misunderstandings: A Social Determinants of Health Lexicon for Health Care Systems. Milbank Q. 2019. Jun;97(2):407–419. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12390. Epub 2019 May 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuels-Kalow ME, Ciccolo GE, Lin MP, Schoenfeld EM, Camargo CA. The terminology of social emergency medicine: Measuring social determinants of health, social risk, and social need. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open. 2020;22(6):18–5. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; 4. Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010. Apr;100(4):590–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein SL, D’Onofrio G. Public health in the emergency department: Academic Emergency Medicine consensus conference executive summary. Acad Emerg Med 2009. Nov;16(11):1037–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alter HJ Foreword to Conference Proceedings, Inventing Social Emergency Medicine. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2019. Nov;74(5S):S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson E, Bernstein E, Xuan Z, Alter HJ Inventing Social Emergency Medicine: Summary of Common and Critical Research Themes Using a Modified Haddon Matrix. Annals of Emergency Medicine 74, S74–S77 (2019). doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.08.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2008. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/csdh_finalreport_2008.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capp R, Kelley L, Ellis P, et al. Reasons for Frequent Emergency Department Use by Medicaid Enrollees: A Qualitative Study. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:476–81. doi: 10.1111/acem.12952. Epub 2016 Mar 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez RM, Fortman J, Chee C, Ng V, Poon D. Food, shelter and safety needs motivating homeless persons’ visits to an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.046. Epub 2008 Oct 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baggett TP, Singer DE, Rao SR, O’Connell JJ, Bharel M, Rigotti NA. Food Insufficiency and Health Services Utilization in a National Sample of Homeless Adults. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:627–34. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1638-4. Epub 2011 Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Seligman H. The Monthly Cycle of Hypoglycemia: An Observational Claims-based Study of Emergency Room Visits, Hospital Admissions, and Costs in a Commercially Insured Population. Med Care 2017;55:639–45. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Cahill R, et al. Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Affect Hospital Utilization Among Older Adults? The Case of Maryland. Population health management 2018;21:89–95. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0055. Epub 2017 Jul 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Measuring Social Determinants of Health among Medicaid Beneficiaries: Early State Lessons. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., 2016. https://www.chcs.org/media/CHCS-SDOH-Measures-Brief_120716_FINAL.pdf Accessed August 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address the Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. July 26, 2010. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2010/hp2020/advisory/SocietalDeterminantsHealth.htm) Accessed August 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2017, September 05). Accountable Health Communities Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm. Accessed August 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massachusetts’ Medicaid ACO Makes a Unique Commitment to Addressing Social Determinants of Health.” https://www.chcs.org/massachusetts-medicaid-aco-makes-unique-commitment-addressing-social-determinants-health/. Accessed June 13, 2018.

- 18.National Quality Forum. NQP Social Determinants of Health Data Integration. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectDescription.aspx?projectID=88247. Accessed August 18, 2021.

- 19.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). Social Determinants of Health. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/health-it-health-care-settings/social-determinants-health. Accessed August 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin MP, Baker O, Richardson LD, Schuur JD. Trends in Emergency Department Visits and Admission Rates Among US Acute Care Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1708–1710. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA. 2010;304(6):664–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Losonczy L, Hsieh D, Hahn C, Fahimi J, Alter H. More than just meds: National survey of providers’ perceptions of patients’ social, economic, environmental, and legal needs and their effect on emergency department utilization. Social Medicine 2015;9:22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Losonczy LI, Hsieh D, Wang M, et al. The Highland Health Advocates: a preliminary evaluation of a novel programme addressing the social needs of emergency department patients. Emerg Med J 2017;35:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SocialEMpact.com, accessed August 16, 2021