ABSTRACT

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccines emerged as a worldwide hope to contain the pandemic. However, many people are still hesitant to receive these vaccines. We aimed to systematically review the public knowledge, perception, and acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries and the predictors of vaccine acceptability in this region.

Methods

We systematically searched databases of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane and retrieved all relevant studies by 5 August 2021.

Results

There was a considerable variation in the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates, from 12% in a study from Israel to 83.3% in Kuwait, although two other studies from Israel mentioned 75% and 82.2% acceptability rates. Concerns about the side effects and safety of the vaccine were the main reasons for the lack of acceptability of taking the vaccine, which was reported in 19 studies.

Conclusion

Several factors, such as age, gender, education level, and comorbidities, are worthy of attention as they could expand vaccine coverage in the target population.

KEYWORDS: Attitude, acceptability, COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccine, Middle East, North Africa, perception, SARS-CoV-2, vaccine

Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) emerged as a pandemic and a serious threat to the public health in 2020.1–4 Many countries have accelerated vaccine research and developed vaccination programs against COVID-19.5–7 With emerging variants that exhibit more transmissibility or disease severity, such as delta and omicron variants, the worldwide hope relies on higher vaccination rates to decrease the disabilities and deaths related to the COVID-19.3,8,9 Although vaccine research has progressed rapidly, public acceptance and negative attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines are significant challenges. The willingness to receivethe COVID-19 vaccine is recognized as a key issue in predictingthe success of a vaccination program.10

The acceptability of the vaccines and people’s attitude toward them determine the rates of vaccinations and serves an important role in containing the pandemic. Several factors were suggested to affect the vaccine acceptability among the general population, such asthe previous experience of vaccine, level of education and knowledge, risk perception and trust, perception of vaccine effectiveness, having underlying diseases, mental and cultural norms, religious and moral beliefs, etc.11–13 Understanding the severity and risks of the COVID-19 is also associated with public awareness of the dangers and encourages people to be more involved in disease prevention.12,14,15 Nevertheless, such factors are not extensively reviewed by the previous studies. The current global acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccines varies from 35% to 98% across countries, indicating that policymakers need to understand the public attitude to assist the large-scale vaccination programs.16–18

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region was affected early in the COVID-19 epidemic, and there were a large number of cases in some countries (e.g., Iran).19 The first COVID-19 confirmed cases in MENA date back to February 2020 and have been reported in the UAE, Iran, and Egypt.20 Although some original studies on vaccine acceptability exist that measure the public perception toward vaccination in the countries of the region, no systematic reviews are available to summarize the findings for this region. Furthremore, the causes of vaccine hesitation and lack of acceptability are not studied in details for the region. Bearing these facts in mind, this study aimed to systematically review thepublic knowledge, perception, and acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines in the MENA countries and the predictors of vaccine acceptability in this region, as making policies revolving around such factors may increase the willingness of the people to receive the COVID-19 vaccines.

Methods

Overview

We systematically searched the online databases of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochraneand retrieved the relevant studies by 5th August 2021. The retrieved records were downloaded into the EndNote 20 program for study selection. The study selection process consisted of two steps; first, the records underwent a title/abstract screening process. Then, studies selectedin the title/abstract screening were included in the full-text screening, and the eligible articles were included in the final review.

Search strategy

We searched for the keywords related to “COVID-19”, “vaccination”, and “MENA and its countries”. The detailed keywords and search strategy be found in Supplementary material 1.

Study selection

We included the original studies that evaluated public attitude, perception, and acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines in the MENA region. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Reviews, systematic review, meta-analyses, and any other studies without original data

Case reports

Abstracts or other studies lacking available full texts

Studies from the world regions other than MENA

Non-English studies

Data extraction

We summarized the included publications into a word table (Table 1) that represents theyear andcountry of study, study design (e.g., cross-sectional study), samplesize, patient’s mean age, gender,comorbidity, history of influenza vaccination (%), participants’ education and occupation, acceptability rate of COVID-19 vaccine (%), reasons for lack of acceptability,respondents’ attitudes toward vaccination,reasons and predictors ofacceptability, and a summary of findings. Three independent researchers undertook this process, and a final investigator reviewed the extracted data and addressedany possible discrepancies between the researchers.

Table 1.

Included studies and summary of their findings

| ID | Author | Country and number | Mean age and male (%) | Comorbidity | Previous influenza vaccination | Education level and occupation | Acceptability rate | Attitudes towards vaccination | Reasons for lack of acceptability | Reason and predictors of positive acceptability | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Almaaytah A, Salama A.21,23 ,24 | Jordan 688 |

44 38.2% |

N/A | N/A | No education at all: 3.2%, Less than high school degree: 6.8%, High school degree: 8.7%, Some college: 64.7%, College degree: 16.6% | N/A | A strong correlation between the participants’ unwillingness to get vaccinated and the perceived potential harms of the vaccine | Perceived stigma, Perceived severity, the Perceived likelihood of infection in the future, Knowledge, Protective behaviors, Perceived potential harms of vaccine, Perceived effectiveness of the vaccine | − Being free of charge - The availability of COVID-19 vaccines |

Jordanians are still hesitant about getting vaccinated against COVID-19, which could be mainly attributed to their perceived uncertainty of the vaccines’ efficacy and toxicity |

| 2 | Alobaidi S.26–28 | Saudi Arabia 1333 |

35.04 ± 11.67 55.2% |

22.8% | N/A | High school and below: 279(20.9), Bachelor: 794(59.6), Masters/PhD: 260(19.5) | 67.1% | Perceived susceptibility construct and perceived benefit construct were important facilitators for a definite intention to vaccinate among the Saudi population. | Being concerned with the safety and side effects of the vaccine under the perceived barriers construct and willingness to get vaccinated | Participants who rated higher confidence in local as well as foreign vaccine reported significantly higher intention to take the vaccination, perception of worry about the likelihood of getting COVID-19 infection | N/A |

| 3 | Aloweidi A29 | Jordan 646 |

28.2 ± 10.8 26.2% |

N/A | 37 (10.3%) | Elementary school: 20 (3.1%), High school: 55 (8.5%), Diploma: 55 (8.5%), Bachelor: 429 (66.4%), Masters: 69 (10.7%), Doctor of Philosophy (PhD): 18 (2.8%) | 35% | N/A | Rumors They Received via Social Media, The Rumors That They Believed in, Side Effects They Heard about | Most Encouraging Factors for Vaccination, Most Influencing Social Media Tools to Encourage Vaccination | Reading a scientific article about the available vaccines showed a significant increase in the rate of willingness to take the vaccines |

| 4 | Alzahrani SH27,30 | Saudi Arabia 3091 |

N/A 39.9% |

81% Chronic disease | 58.9% | Secondary education: 42 (1.4%), Secondary: 302 (9.9%), University: 2104 (69%), Post-graduate: 600 (19.7%) | 24.4% | About half of Saudis are unwilling or undecided about getting the COVID-19 vaccine | Short clinical testing period, vaccine side effects, preference for acquired immunity via contracting the COVID-19 infection. | Males, Saudis, individuals with less than secondary education, residence in the southern region, and individuals with perceived risks of COVID-19, Participants who had received the influenza vaccine within the past year were | About half of Saudis are unwilling or undecided about getting the COVID-19 vaccine, representing a significant public health threat and impediment to the goal of attaining herd immunity. |

| 5 | Ansari-Moghaddam A31,54 | Iran N/A |

37.73 ± 12.27 46.2% |

N/A | N/A | University degree: 83.7%, Undergraduate degree: 47.3%, Graduate degree: 36.4% | N/A | N/A | N/A | Perceived susceptibility, Perceived severity, Perceived self-efficacy, Perceived response efficacy, intention | The PMT constructs are useful in predicting COVID-19 vaccination intention |

| 6 | AsadiFaezi, N32,37 | Iran 1880 |

N/A 45.85% |

13% | N/A | High school: 95 (5.05%), Diploma: 231 (12.29%), Bachelor: 506 (26.91%), MSc: 529 (28.14%), Doctorate: 519 (27.61%) | 66.81% | Individuals with higher education believe that India, the USA, the UK, and Europe produce the best vaccine, while healthcare workers think of China, India, Russia, and Cuba. | Concerned about the reports of post-vaccination mortality, The early preparation of the vaccine, the side effects of vaccines, believed rumors such as changes in the human genome in the vaccine. | Vaccination can help control the recent epidemic, to effectively reduce mortality from COVID-19 disease. | A multifaceted approach to facilitate vaccine uptake that includes vaccine education, behavioral change strategies, and health promotion. |

| 7 | AlAwadhi EA33 | Kuwait 7241 |

38.03 27.3% |

25.1% Chronic illness | 16.56% | No formal education: .29, High school or less: 9.11, University: 71.87, Post-graduate: 18.73 | 67% | knowledge of COVID-19, the perception of being prepared to protect oneself, taking protective measures, informing oneself about the coronavirus, having high confidence in the media, doctors, hospitals, or the Ministry of Health | Increased age, being female, an increased belief that the measures are taken isgreatly exaggerated, and not taking the seasonal influenza vaccine in 2019 | To take the COVID-19 vaccine if it was available and recommended in the country. Informing oneself about the coronavirus and perceiving the probability of getting infected with seasonal influenza | This increase in vaccine hesitancy reveals a challenge in achieving high inoculation levels and the need for effective vaccine-promotion campaigns and increased health education in the country. |

| 8 | Baghdadi, L. R33,34 |

Saudi Arabia 329 |

N/A 48.2% |

19.8% Chronic diseases | 55.9% | Physician: 44.6%, Nurse: 19.4%, Others: 36.0% | 70.7% | Vaccine acceptors had greater odds about the belief that COVID-19 is a bad disease and is dangerous for patients, and the vaccine would be beneficial | The vaccine rejecters believed that HCWs must have the freedom of choice to accept or reject the vaccine. | Perceived susceptibility to the COVID-19 infection, Encouragement from close family and friends, colleagues, and supervisors | Most of the HCWs were willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine. The intention of accepting the vaccine was not associated with previous exposure to the influenza vaccine. |

| 9 | Burhamah, W35,36 |

Kuwait 2345 |

29 41% |

Diabetes, Hypertension, Heart attack, Asthma,Hypothyroidism, Depression, Cancer, Inflammatory bowel disease | N/A | High school: 481 (20%), College diploma: 323 (14%), Bachelor’s degree: 1,290 (55%), Master’s degree/PhD: 251 (11%) | 83% | Most people were not opposed to the vaccine and agreed to Use it |

Waiting for the vaccine to work for others, lack of complete protection against the virus, This is a conspiracy, The vaccine is harmful and unsafe, The vaccine gives the person the virus. | The pandemic ends faster, and life returns to normal; pprotectionagainst the virus, wanted to be able to travel in the future. | Vaccine hesitancy could jeopardize the efforts to overcome this pandemic; therefore, intensifying nationwide education and dismissal of falsified information is an essential step toward addressing vaccine hesitancy. |

| 10 | Dror, A. A28,29 | Israel 1112 |

N/A N/A |

N/A | N/A | Doctors: 338, Nurse: 211, Others: 563 | 75% | N/A | Quality control, Side effect, Associated of covid, Wait until tested by other, Wait for next year, Pregnancy, Doubted efficiency, Covid symptoms are mostly mild, Physiological immunity is better | The most significant positive predictor for people to accept a potential COVID-19 vaccine is their current influenza vaccination status. | The majority of the responders’ concerns, both among healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers alike, are due to public uncertainty of the COVID-19 vaccine’s rapid development. |

| 11 | El-Elimat, T27,55 | Jordan 3100 |

29 32.6% |

13.4% Chronic diseases | 9.4% | School education: 269 (8.7),Undergraduate: 2,169 (69.9), Postgraduate: 662 (21.4) | 37.4% | COVID-19 vaccines made in Europe or America are safer than those made in other world countries, Most people will refuse to take the COVID-19 vaccine once licensed in Jordan, The government makes the vaccine available for all citizens for free | Concerned that the COVID-19 pandemic is a conspiracy, Not trust any information. | Participants who believed that the COVID-19 pandemic is a conspiracy and those who did not trust any information were less acceptable for the vaccine. | Jordan is one of the lowesteligible countries for the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccines have raised safety and cost concerns with the refusal. |

| 12 | Elgendy, M. O21,37 |

Egypt 871 |

N/A 46.6% |

22.9% Chronic diseases | N/A | Colleague student:15.5%, Bachelor: 63.8%, Master/PhD: 20.7% | N/A | A person can be infected with coronavirus more than one time, Herd immunity is enough to protect everyone from the coronavirus | Believed that the vaccine itself may infect them with coronavirus. | The vaccine is the best way to protect against coronavirus and its complications. Necessary to take the coronavirus vaccine even if the person has already been infected with the coronavirus. | Participants were satisfied in terms of acceptance of the vaccine, there are some concerns about it due to insufficient clinical trials and fear of its side effects. |

| 13 | Rana Abu-Farha30,36 | Jordan-Iraq-Saudi Arabia-Lebanon 2,925 |

27 ± 16.0 37.6% |

13.5% Chronic disease | 38.7% | School level or below 7.2%, Diploma 11.9%, bachelor or graduated degree 80.9%, biomedical degree 45.8% Monthly income < $500 (49.7%), $501 - $1,000 (26.4%), >$1,000 (21%) |

25% | 32.6% hesitate and 42.5% denied the willingness to take vaccine. | Being female, previous infection of COVID-19 | Predictors: Living in Saudi Arabia and Iraq, being unmarried, having a monthly income more than $1,000, having a medical degree, having high fear from COVID-19 and feeling of being at risk of being infected, and the previous injection of Influenza vaccine. | Of those participants who were willing to receive the vaccine, 60% were ready to pay for the vaccine in case not covered bythe government. Also, 50% of acceptors preferred to receive American vaccines and 30% of them were unsure about the best vaccine. Also, 11% stated that any vaccine is good. |

| 14 | Rana K Abu-Farha38,39 | Jordan 1,287 |

30.1 ± 9.7 53% |

9.2% Chronic disease | 57.4% | School-level or lower (30.6%), University or higher (69.4%), biomedical degree (13.1%) | 36.1% | 18.1% were willing to allow their children to receive the vaccine. 16.2% had fear of COVID-19. | Not wantingto be challenged bythe virus (54.7%), fear (40.7%), lack of time (40.4%), and mistrust in pharmaceutical companies (38.9%) | Reasons: Tendency to return to normal life (73.2%) and help to find a treatment for COVID-19 (68.1%) | Higher education was associated with lower willingness. |

| 15 | Carina Kasrine Al Halabi40,56 | Lebanon 579 |

24.94 ± 9.45 23.8% |

30.7% Pregnant or chronic disease 30.7% | 40.4% | Complementary or less 6%, secondary 14.5%, university 79.4% | 21.4% | 40.9% refused to receive vaccine. | Being female and being married were significantly associated with lower odds of agreeing with vaccination. | N/A | N/A |

| 16 | Sabria Al-Marshoudi36,41 | Oman 3000 |

38.2 ± 10.45 76% |

16.3% Chronic disease 16.3% | N/A | Illiterate 8%, pre-secondary school 54.64%, post-secondary and higher 37.32%. Employed 71.39% |

56.8% | 59.3% had a concern about the vaccine, 34% had concerns because of doubts about the efficacy and safety of the vaccine, and 56.8% would advise others to take the vaccine. | Uncertainty about the vaccine safety (22.6%), beliefof non-effectiveness of vaccine (1.9%), COVID-19 is not a serious disease (1.1%), fear from injection (1.1%), no time (.3%), religious reasons (.2%) | Being male and being non-Omani, having a chronic disease, especially diabetes mellitus, being illiterate, and being employed were predictors of being willing to be vaccinated. | Pregnant women were less likely to be vaccinated. Those who heard about the benefits of vaccines from their friends were more willing to be vaccinated. |

| 17 | Abdel-Hameed Al-Mistarehi42,46 | Jordan 2,208 |

33.2 ± 13.5 44.3% |

13.2% Chronic disease |

32% | High school or lower 15%, university degree 85%. Employed 39.4%, unemployed or retired 28%, Being in the medical field, 29.4% |

30.4% | 36.4% were unwilling, and 31.5% were indecisive about takingthe vaccine. 20.1% agreed to vaccinate their children, and 41.7% agreed to encourage the elderly to receive the vaccine. | Concerns about safety and side effects (66.7%), effectivity, and length of protection of vaccines (33.2%) | Being younger adult and male, being unmarried, do not having children, having a high level of education, being employed or student, being healthcare staff, and the previous receive of flu vaccine. | Perception of COVID-19 risks and benefits of vaccine were predictors. |

| 18 | Mohammed Al-Mohaithef43,47 | Saudi Arabia 992 |

≥18 years old 34.1% |

N/A | N/A | Diploma 30%, Graduate 50%, postgraduate 20%. Employed 60%, Not-employed 40%. | 64.7% | N/A | N/A | In older age groups, married, non-Saudi, and government employees’ willingness to be vaccinated was high. | Being above 45 years old and married were predictors of accepting vaccination. |

| 19 | Reem Al-Mulla44,50 | Qatar 462 |

≥18 years old 36.5% |

N/A | 45% | University students 50%, employee 50%. Diploma/undergraduate 58.4%, postgraduate 41.6% |

62.6% | 37.4% were unwilling to take the vaccine. Most of them agreed that being vaccinated is important to end the pandemic. | Concern about safety and effectiveness for themselves and their children. | Participants who were male, 45 years and older, health-related students, or employees showed a higher rate of vaccine acceptance. | A knowledge score of 53% was high. Having a higher education level, being non-Qataris, and being an employee, were associated with higher rates of vaccine acceptance. |

| 20 | Walid A. Al-Qerem52 | Jordan 1,144 |

≥18 years old 33.5% |

15% | 12.1% | High school and less 6.9%, Diploma 7%, academic education 86.1%. Working or studying in the medical field 47.1%. Monthly income <500$ (26.3%), 500-1000$ (41.2%), and >1000$ (32.5%). |

36.8% | 36.8% were unwilling, and 26.4% were unsure of takingthe vaccine. Those with low or medium monthly income and those who did not know someone infected with COVID-19 had significantly decreased odds of having high knowledge score about COVID-19. | Concerns about efficacy and newness of vaccine (98.3%), and lack of trust in the vaccine (81%). Only 1.9% believe that there is a cure for COVID-19 | Knowing someone who was infected with COVID-19 and working/studying in the medical field weresignificantly associated with willingness to take the vaccine. There was a significant relationship between the perception of the seriousness of COVID-19 and lower odds of unwillingness to take the vaccine. |

Those who had a history of COVID-19 infection were significantly more adherence to quarantine procedures. Being female, being married, having children, and having a diploma degree areassociated with unwillingness to the vaccine. |

| 21 | Mariam Al-Sanafi45,50 | Kuwait 1,019 |

34 ± 9.7 38.6% |

17.9% | N/A | Undergraduate degree 65%, postgraduate degree 35%. All participants were healthcare workers, including 90% in public and 10% in private sectors. | 83.3% | 9% were not willing and 7.7% were not sure about taking the vaccine. 62.6% preferred to take mRNA vaccines and 69.7% preferred to take Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. | Hesitance about taking vaccines was significantly associated with the embrace of vaccine conspiracy beliefs. Those who received information about the vaccine from social media, TV programs, and the news showed a higher rate of hesitancy. | Higher acceptance in males, participants of Kuwait nationality, physicians and dentists, those with postgraduate education level, and public sectors’ workers. | Ahigher rate of unwillingness to take the vaccine wasseen in females, those with a lower level of education, nurses, laboratory workers, and private sector employees. |

| 22 | Majid Al-abdulla34,39 | Qatar 7,821 |

≥18 years old 59.4% |

22.2% | 46.6% | High school 10.4%, University 76.8%, trade and vocational 12.8%. Employed 82.9%, unemployed or retired 17.1%. Healthcare worker 19.8% |

60.5% | 20.2% were unwilling, and 19.8% were unsure about taking the vaccine. 92.1% believethat natural exposure to the virus gave the safest protection. | Concerns about the safety of vaccines (53.8%) and long-term side effects (47.9%). Vaccine hesitancy wassignificantly associated with the belief of insufficient vaccine testing, financial motivation of authorities, and safe protection of natural exposure to infection. | Participants own understanding of the infection (36.1%) and understanding of the vaccine (43.4%). | Citizens of Qatar, older ages, self-employed or retired ones, singles, and females were more hesitantabout taking the vaccine. Participants who had flu vaccines were significantly less likely to be vaccine hesitators. |

| 23 | Eiman Al-Awadhi45 | Kuwait 7,241 |

38.03 27.3% |

25% | 16.6% | High school or less 9.4%, University 71.9%, postgraduate18.8%. Income: <699 KD (30%), 700-2,399 KD (56.2%), >2400 (13.8%) | 67% | Perceived knowledge (5.4/7), real knowledge (6.2/7) | Predictors: Being female, increased age, increased the belief that the measures taken are greatly exaggerated, and not taking the flu vaccine in last year. | Being male, ages 18-28 years, an education level of high school or less, a low income, being single. knowledge of COVID-19, correctly identifying protective measures, having high confidence in the media, doctors, hospitals, believing that the government decisions are fair, and taking the influenza vaccine in 2019. | Various factors affect the vaccination acceptability, positively or negatively, discussed in the columns |

| 24 | Eman Ibrahim Alfageeh46 | Saudi Arabia 2,173 |

≥18 years old 57.4% |

26.1% | 66.3% | High school or below 28%, University 72%. Employed 63.4%, unemployed or retired 23.6%, student 13%. <3000 SAR (20.2%), 3000–20,000 (60.8%),≥ 20,000 SAR (19%). |

48.4% | 52% were not willing to take the vaccine. | Predictors: history of vaccine refusal | Predictors: southern region residency, received the flu vaccine, believe in mandatory COVID-19 vaccination, high level of concern about contracting COVID-19. | Participants who were male, hadan income level ≥30,000 SAR, were residents of the southern region, and previously received the flu vaccine, and had experienced COVID-19 infection were more likely to be vaccinated. |

| 25 | Elharake, J.A.48,57 | Saudi Arabia 23,582 |

≥18 years old 52.4% |

14.6% | N/A | High school (2.1%), some college (5.7), college (40.2%), Graduate/Professional (51.8%) | 64.9% | 35.1% were not willing to take the vaccine. | 58.5% reported fear of potential side effects, 34.5% lack of trust for those creating and distributing the vaccine, 6.6% do not believe vaccines work. | Males accept a COVID-19 vaccine more than females. | Females were less likely to get vaccination due to the lack of data on the effects of the vaccine on the risks of pregnancy. |

| 26 | Fares, S.32,53 | Egypt 385 |

From 17 to 66 years old 18.70% |

N/A | N/A | Baccalaureate degree (40%), Professional diploma (9.09%), Master’s degree (29.87%), and MD degree (17.40%) | 21% | The majority of participants did not decide yet (51%), and 28% percent were not likely to get vaccinated. | Lack of enough clinical trials (92.4%), and fear of vaccine’s side effects (91.4%) | Risks of Covid-19 (93%), the safety of the vaccine (57.5%), the effectiveness of the vaccine (56.25%), and traveling facilitation (43.75%) | There is a high level of concern for vaccine safety. males accept vaccination more than females. |

| 27 | Fayed, A.A.40 | Saudi Arabia 1539 |

≥18 years old 41.4% |

Diabetes, Hypertension, asthma, Cardiac diseases. | 19.5% | Minimal schooling 20.2%, University 65%, and higher education 14.8%. | 59.5% | 39% of the participants were vaccine-hesitant | Vaccine safety, efficacy, and misleading information about the pandemic | N/A | Older participants and males were more likely to get vaccinated than younger adults and females. |

| 28 | Green, M.S.49,58 |

Israel 957 |

30 years of age or older N/A |

N/A | Among the males, 43.4% of Jewish and 37.3% of |

12 years ofprofessional training,47.8% Academic degree 52.2%. |

Jewish M 27%, F 14%. Arabs M 23%, F 12% | N/A | Misinformation about vaccines. | N/A | Higher education was associated with less vaccine hesitancy. |

| 29 | Hammam, N.47,59 | Egypt 187 |

N/A 15% |

N/A | 18.5% | All the participants are rheumatology staff members | 30.5% | Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines is low. | Quickly made vaccines, and side effects | N/A | N/A |

| 30 | Hershan, A.A.39,51 | Saudi Arabia 186 |

≥18 years old 73.15% |

N/A | 67% | health field participants at the University of Jeddah |

55.9% | Medium acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines | Side effects, safety, and efficacy. | N/A | N/A |

| 31 | Magadmi, R.M.32,50 | Saudi Arabia 3101 |

≥18 years old 41.7% |

25% | 40% | Elementary .8%, secondary 9.7%, University 63.9% and higher education 25.4%. | 44.7% | Older females, no history of influenza vaccine uptake, and negative beliefs toward vaccination. | Safety (55.4%), effectiveness (56.1%), and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 | Taking the Influenza vaccine previously was a positive factor. | N/A |

| 32 | Maraqa, B.52,60 | Palestine 1159 |

≥18 years old 37.1% |

21.7% | 37.6% | Health care workers | 37.8% | 31.5% were undecided, and 30.7% were not willing to take the vaccine. | No long-lasting immunity, significant and long-term side effects. | Males were more likely to take vaccines. | N/A |

| 33 | Mejri, N.31,46 | Tunisia 329 |

54 years old 21.3% |

36.4% | 16.1% | N/A | 50.5% | 50.5% are willing to take the vaccine, 21.2% were not decided yet, and 28.3% refused to take the vaccine. | Side effects (33.1%), effectiveness (24.9%), and no need forthe vaccine because COVID-19 is not a severe disease (3%) | Susceptibility COVID-19, because cancer patients are at greater risk | N/A |

| 34 | Mohammad, O.25,53 | Syria 3,402 |

≥18 years old 35.8% |

13.6% | N/A | Postgraduate (16.02%), school (14.46%), and high education (66.78%) | 35.92% | 35% are willing to take the vaccine, 46% were not decided yet, and 17% refused to take the vaccine. | Side effects and efficacy of the vaccines. | Male gender, younger age, rural residence, not having children, smoking, fear about COVID-19, and high vaccination knowledge. | Males were more likely to accept the vaccine than females. |

| 35 | Omar, D. I.24,61 | Egypt 1,011 |

29.35 ± 10.78 41.2% |

Diabetes, Cancer, Kidney or liver disease, And Overweight/obesity. |

34.6% | Primary 4.6%, Preparatory education 2.2%, Secondary education 22.9%, University 49.5%, Post graduate 20.8%, Student 41.3%. |

27.1% | 54% reported COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and 21% of them reported vaccine non-acceptance, while 27.1% preferred receiving the Pfizer vaccine. | Unforeseen effects of the vaccine, female sex, urban residence, university/post-graduate, married respondents, absence of a history of allergy to food or drugs, younger age, those never had the flu vaccine. | N/A | N/A |

| 36 | Yuval Palgi36,62 |

Israel 254 |

60.04 ± 15.44, range 24-100 40.6% |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | depression and peritraumatic stress (ORs >2), anxiety (OR > 3) |

N/A | N/A |

| 37 | Ameerah M N Qattan59,63 |

Saudi Arabia 673 |

18-60< 67.06% |

79.4% Chronic condition | 71.32% | N/A | 50.52% | N/A | N/A | Male healthcare worker | N/A |

| 38 | Qunaibi, E.60,64 |

21 Arabcountries 5708 |

30.6 ± 10 55.6% |

14% Chronic diseases |

5.6% | 67.9% bachelor’s degree or higher | Rate of vaccine hesitancy among Arabic-speaking HCWs 25.8% | The western regions of the Arab world (Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria) had the highest rates of hesitancy | Concerns about side effects and distrust of the expedited vaccine production and healthcare policies. | Age of 30–59, previous or current suspected or confirmed COVID-19, female gender, not knowing the vaccine type authorized in the participant’s country, and not regularly receiving the influenza vaccine. | N/A |

| 39 | Rabi, R.61,65 | Palestine 638 |

Under 30 25%, 30–49 55.8%, Above 50 19% 17% |

28% | 38.5% | Nurse | 40% planned to get the vaccine when available | N/A | Concern about long- term side effects, lack of vaccine knowledge, Vaccine safety, fear of injection, natural immunity preference, media misrepresentation, and getting COVID- 19 from the vaccine. | age | N/A |

| 40 | Rosental, H.41,62 |

Israel 628 |

Med.S. 28.06 ± 3.33 50%, Nurse.S26.04 ± 3.74 16% | NA | Med. 81.6% Nurse. 47.6% |

Med. Nurse. | 82.2% | Medical. S expressed higher intentions of getting vaccinated than nursing. S (88.1% vs.76.2%) | Safety and quality Not tried on others, Low efficiency, Temporary solution, natural immunity is preferable. Female nurses. |

N/A | N/A |

| 41 | Saied, SM.6342 | Egypt 2133 |

20.24 ± 1.8 34.8% |

NA | 10.3% | Medicine 34.1%, Physical medicine 34.3%, Dentistry 12%, Nursing 12.8%, Pharmacy 6.8%. |

34.9% | Refusal 19% Hesitant 45.6%. 67.9% of students believed that the way to overcome the COVID‐19 pandemic is mass vaccination (56.5%), |

adverse effects of the vaccine (96.8%), its ineffectiveness (93.2%) and enough testing (80.2%), safety (54.0%), acquisition of COVID-19 from the vaccine itself 63.3% Insufficient information regarding vaccine 72.8%, its adverse effects (potential 74.2% Unknown 56.3%, financial cost 68%, insufficient trust in the vaccination source 55%. |

N/A | Most students were not against vaccination (95.1%) |

| 42 | Sallam, M.26,64 |

Arab-speaking countries 3414 |

31 32.7% |

34.6% | 30.9% | 75% undergraduate study level | 29.4% | inject microchips into recipients 27.7%/that the vaccines are related to infertility 23.4% Females, lower educational levels, and respondents rely on social media platforms as the main source of information. |

N/A | A reliance on social media as the main source of information about COVID-19 vaccines was associated with vaccine hesitancy. | |

| 43 | Tahir, A.I.22,65 | Iraq 1188 |

N/A 47.2% |

15% | 22% | Lower than high school 67 High school 79 Diploma/bachelor 825 H.diploma/Master/Ph.D 217 |

N/A | Fear of side effects such as blood clotting (45.03%) (p < .016). 39.9% and 34.01%, were afraid of AstraZeneca and Pfizer (p < .001) 4.63% had fear of Sinopharm |

N/A | Fear, social media use (51.8%), and losing family members, (previous seasonal influenza vaccine, previous infection, chronic medical diseases) show no relationship. | N/A |

| 44 | Talmy, T.23,65 | Israel 511 |

21.5 ± 3.6 63.6% |

N/A | N/A | N/A | 77.7% | Hesitancy remains a concern with only 62.4% | N/A | On-site COVID-19 vaccine rollout joined with primary care communication interventions may maximize vaccine uptake within a young-adult community. Highly accessible vaccine sites and engagement of primary care physicians with their communities may increase vaccination rates |

N/A |

| 45 | Temsah, M.52,65 | Saudi Arabia 15,124 |

37.28 ± 8.99 47.6% |

23.8% | N/A | Physician 42.1 Nurse 50.1% Other healthcare providers (HCPs) 7.8% |

24.4% ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine, 20.9% RNA BNT162b2 vaccine | 18.3% reported refusing the Ad5- vectored vaccine and 17.9% refusedthe Gam-COVIDVac vaccine. | N/A | Their perceptions of the vaccine’s efficiency in preventing the infection (33%), their personal preference (29%), and the vaccine’s manufacturing country (28.6%) were among the factors that affected the acceptability. | N/A |

Results

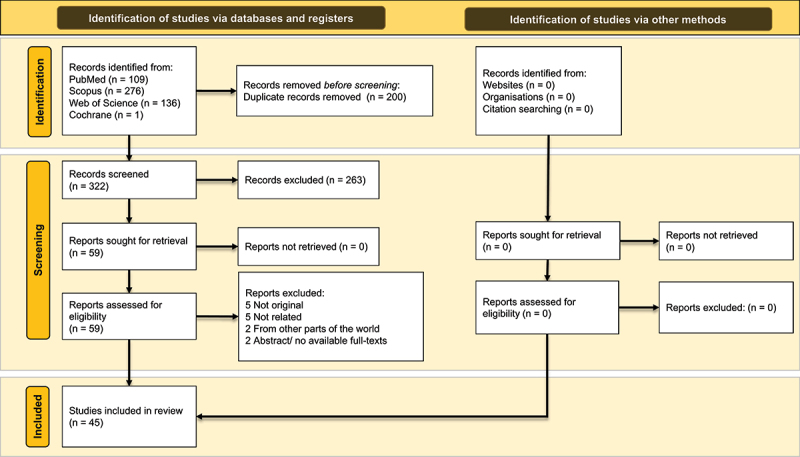

A total of 45cross-sectional studies were included in this review (Figure 1). All studies wereconducted usinga phone interview or a self-reported online questionnaire. Most of the studies were fromSaudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel, with 11, 7, and 5 studies, respectively.The majority of studies had a high number of participants;15 of them polled 1000–3000 participants, 12 polled over 3000 participants, and 18had less than 1000 participants.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart for included articles

There hasbeen a considerable variation in COVID-19 vaccine acceptance between the studies. The highest acceptance rate was reported in a survey conducted in Kuwait (83.3%); while, the lowest rate of acceptance was reported in a survey conducted in Israel with an acceptance rate of 12%. Some countries had higher acceptance: one study in Kuwait (83%), two studies in Israel (82.2% and 75%),andone study in Saudi Arabia (70.7%).The acceptance rate was not reported in six studies. Concernsrelated to theside effects and safety of the vaccine were the main reasons for the lack of acceptability of the vaccines reported in 19studies.

A considerably wide variety of acceptability rates have been reported across thestudies included in this review.Depending on the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age, gender, education, and region.Elgendy and Abdelrahim, Fares et al., and Temsah et al. reported that the safety and efficacy of the currently available COVID-19 vaccines against severe complications is another predictor of high vaccine acceptability.21,22,25 The type of vaccine, side effects, and its manufacturing company has also played a pivotal role in people’s willingness to receive vaccines.22,26 Interestingly, other studies conducted on younger than 25-year-old participants have also shown a high rate of vaccine acceptability.29 In contrast, studies with a wider range of participants that included middle-aged adults demonstrated lower vaccine acceptability rates than the groups mentioned above.25,30,31

Individuals who have received their influenza vaccine appeared to be more willing to get vaccinated against the COVID-19,27,28,32–35 Nevertheless, Baghdad et al. did not find correlations between intentions for accepting influenza vaccinations and the COVID-19 vaccines’ acceptability,37 while Dror et al. reported influenza vaccine acceptance as the most significant predictor of willingness to the COVID-19 vaccines.34

Males tended to have higher acceptability rates compared to the women,36–38,40–43 Patients with underlying conditions that found themselves at higher risk of severe COVID-19 had better acceptability for the COVID-19 vaccines.44, Participants involved in healthcare services tend to have a higher vaccine acceptability rate compared to other groups. In a group of 628 medical students and nursing students in Israel, the acceptability rate was 82.2%.45 However, the acceptability rate among 2133 Egyptian medicine, nursing, dentistry, and pharmacy students reported to be 34.9%.39 Temsah et al. also reported a relatively low acceptability rate (20.9–24.4%) in a sample of 15,124 physicians, nurses, and health care providers in Saudi Arabia.22 Those with non-medical but higher degrees are more likely to find their desired information about the vaccines and understand the arguments supporting vaccination.

Discussion

In this study, here we reviewed the acceptability rate and influencing factors of COVID-19 vaccinationsuch as age, sex, education level, and comorbidities of the participants. The reasons and rationale leading to higher or lower acceptability rates are discussed here to enhancethe awareness ofvaccine acceptability and influencing factors.

Whether subjective or objective, various factors were shown to contribute to a high vaccine acceptability rate among subjects. Being concerned about the risk of contracting COVID-19 infection, especially among those with chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, contributed significantly to the willingness to get vaccinated.30,35,38,40,46 Another contributing factor has been the strong urge to help eradicate the COVID-19 pandemic and recommence everydaylife21,41,42,48 by achieving herd immunity through vaccination. Moreover, Burhamah et al. and Fares et al. reported a tendency to travel as a criticalfactor in increasing vaccine acceptability.25,41

Several studies demonstrated that subjects who had previously received influenza vaccine were more likely to accept COVID-19 vaccine injection,27,32,35,46,49 which may be the result from observing vaccines’ effectiveness in preventing flu. Two cross-sectional studies in Qatar and another in Syria stated that comprehensive knowledge of vaccines and their function accounts for another factor leading to high vaccine acceptability.30,36

As different studies have reported various vaccine acceptability rates concerning the mean age of participants, it is difficult to make a conclusive deduction. However, generally speaking, as reported by Mejri et al., those with an older age have shown more willingness for receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.47 This may stem from the fact that they are at greater risk of being infected and having severe complications due to older age and comorbidities

The results of included studies imply that generally, women hesitate more for getting vaccinated. Studies with a male percent of more than 40% reported a significantly higher rate of vaccine acceptability than most of the studies involving more women,36–38,40–42,43 However, the intriguing point is that some exception studies that, despite involving more women, demonstrated a high rate of acceptability,50,51 surprisingly sometimes even higher than other studies.52

Patients at higher risk of COVID-19 infection, particularly diabetic and immunocompromised patients,have more tendency to get their COVID-19 vaccine shot. In a report from Kuwait in which 24% of the participants had at least one medical condition such as diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and asthma, 83% of participants were convinced to take their vaccine.

The impact of one’s education level on vaccine acceptability could not be emphasized enough, as higher education and especially medical education are due to help people understand the cons and pros of vaccines, as well as their mechanism of action and thus make them less afraid of the upcoming complications. The acceptability of vaccines could be diminished by conspiracy beliefs, especially among those with lower education levels.31

Just acceptability and hesitancy themselves, the reasons for them also vary with education level, age, and medical conditions.The uncertainty about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines,24,36,44,53 misbeliefs, and conspiracies spread through social media27,28,52 are often reported as the reasons for mistrust of COVID-19 vaccines. Some claimed the lack of sufficient clinical trials as the logic of their hesitancy.25 Many hesitate the vaccines because they do not have trust in their efficacy. Either not believing the authorities or the clinical trials, these participants tend to protect themselves against COVID-19 through natural exposure to the virus, which is not supported by the same evidence compared to vaccines.36

Conclusion

The acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines depends on many variables and could not be predicted using only one or a few of them. Age, education level, and comorbidities are the main prognostic factors based on which a higher or lower acceptability rate could be explained. Furthermore, evaluation of the popular reasons leading to lack of acceptability would result in a better understanding of the concerns of the population, which could empower the authorities to plan for better vaccination coverage. Also, approaching each group of people with a coherent strategy and providing them with relevant information will with great chance facilitate the process of vaccination. At last, better control ofvaccine information spread through social networks can be helpful in diminishing the conspiracy beliefs leading to mistrusting the vaccination process.

Acknowledgments

The present study was conducted in collaboration with Khalkhal University of Medical Sciences, Iranian Institute for Reduction of High-Risk Behaviors, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and Walailak University.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Authors' contributions

All authors participated in all stages of the manuscript drafting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability materials

The authors stated that all information provided in this article could be shared

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was extracted from the research project with code IR.KHALUMS.REC.1399.001 entitled “Investigation of effective drugs for people affected by Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Imam Khomeyni hospital” conducted at Khalkhal University of Medical Sciences in 2020.

References

- 1.Cucinotta D, Mjabmap V.. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venugopal VC, Mohan A, Lkjapp C.. Status of mental health and its associated factors among the general populace of India during COVID‐19 pandemic. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020;e12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SeyedAlinaghi S, Mirzapour P, Dadras O, Pashaei Z, Karimi A, MohsseniPour M, Soleymanzadeh M, Barzegary A, Afsahi AM, Vahedi F, et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 different variants and related morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00524-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SeyedAlinaghi S, Mehrtak M, MohsseniPour M, Mirzapour P, Barzegary A, Habibi P, Moradmand-Badie B, Afsahi AM, Karimi A, Heydari M, et al. Genetic susceptibility of COVID-19: a systematic review of current evidence. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00516-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO, World Health Organization World Health Organization . Genova S. Draft landscape and tracker of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. 2021. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehraeen E, Dadras O, Afsahi AM, Karimi A, MohsseniPour M, Mirzapour P, Barzegary A, Behnezhad F, Habibi P, Salehi MA, et al. Vaccines for COVID-19: a review of feasibility and effectiveness. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21. doi: 10.2174/1871526521666210923144837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehraeen E, SeyedAlinaghi S, Karimi A. Can children of the Sputnik V vaccine recipients become symptomatic? Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(10):3500–16. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1933689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehraeen E, Salehi MA, Behnezhad F, Moghaddam HR, SeyedAlinaghi S. Transmission modes of COVID-19: a systematic review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(6):e170721187995. doi: 10.2174/1871526520666201116095934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SeyedAlinaghi S, Karimi A, MohsseniPour M, Barzegary A, Mirghaderi SP, Fakhfouri A, Saeidi S, Razi A, Mojdeganlou H, Tantuoyir MM, et al. The clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in HIV-positive patients: A systematic review of current evidence. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2021;9(4):1160–85. doi: 10.1002/iid3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Y, Hu Z, Zhao Q, Alias H, Danaee M, Lpjpntd W. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(12):e0008961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger JA. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dadras O, Alinaghi SAS, Karimi A, MohsseniPour M, Barzegary A, Vahedi F, Pashaei Z, Mirzapour P, Fakhfouri A, Zargari G, et al. Effects of COVID-19 prevention procedures on other common infections: a systematic review. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00539-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SeyedAlinaghi S, Afsahi AM, MohsseniPour M, Behnezhad F, Salehi MA, Barzegary A, Mirzapour P, Mehraeen E, Dadras O. Late complications of COVID-19; a systematic review of current evidence. Arch Emerg Med. 2021;9(1):e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahin MAH, Rmjmecp H. Risk perception regarding the COVID-19 outbreak among the general population: a comparative Middle East survey. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2020;27(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Echoru I, Ajambo PD, Bukenya EM. Acceptance and risk perception of COVID-19 vaccine in Uganda: a cross sectional study in Western Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2020;10(21): 1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Sbje O. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine . 2020;26:100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, Kimball S, El-Mohandes A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–28. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, Jit M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):1023–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karamouzian M, Njtlgh M. COVID-19 response in the Middle East and north Africa: challenges and paths forward. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(7):e886–e7. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30233-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehtar S, Preiser W, Lakhe NA, Bousso A, TamFum J-J, Kallay O, Seydi M, Zumla A, Nachega JB. Limiting the spread of COVID-19 in Africa: one size mitigation strategies do not fit all countries. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(7):e881–e3. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30212-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elgendy MO, Abdelrahim MEA. Public awareness about coronavirus vaccine, vaccine acceptance, and hesitancy. J Med Virol. 2021;93(12):6535–43. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tahir AI, Ramadhan DS, Taha AA, Abdullah RY, Karim SK, Ahmed AK, Ahmed SF. Public fear of COVID-19 vaccines in Iraqi Kurdistan region: a cross-sectional study. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2021;28(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s43045-021-00126-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talmy T, Cohen B, Nitzan I, Ben Michael Y. Primary care interventions to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Israel Defense Forces soldiers. J Community Health. 2021;46.1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almaaytah, A. and Salama A., Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among jordanian adults: a cross sectional study. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 2020. 11(11): p. 1291–1297 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohamad O, Zamlout A, AlKhoury N, Mazloum AA, Alsalkini M, Shaaban R. Factors associated with the intention of Syrian adult population to accept COVID19 vaccination: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1310. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11361-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, Yaseen A, Ababneh NA, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: a study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alobaidi S. Predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccination among the population in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a survey study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1119–28. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S306654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alabdulla M, Reagu SM, Al-Khal A, Elzain M, Jones RM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in Qatar: a national cross-sectional survey of a migrant-majority population. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2021;15:361–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alzahrani SH, Baig M, Alrabia MW, Algethami MR, Alhamdan MM, Alhakamy NA, Asfour HZ, Ahmad T. Attitudes toward the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: results from the Saudi residents’ intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (SRIGVAC) study. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):798. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.AlAwadhi EA, Zein D, Mallallah F, Haider NB, Hossain A. Monitoring COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Kuwait during the pandemic: results from a national serial study. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1413–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu-Farha R, Mukattash T, Itani R, Karout S, Khojah HMJ, Abed Al-Mahmood A, Alzoubi KH. Willingness of Middle Eastern public to receive COVID-19 vaccines. Saudi Pharm J: SPJ. 2021;29(7):734–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alawadhi E, Zein D, Mallallah F, Haider NB, Hossain A. Monitoring COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in kuwait during the pandemic: results from a national serial study. Risk Manage Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1413–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magadmi RM, Kamel FO. Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among the general population in Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1438. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baghdadi LR, Alghaihb SG, Abuhaimed AA, Alkelabi DM, Alqahtani RS. Healthcare workers’ perspectives on the upcoming COVID-19 vaccine in terms of their exposure to the Influenza vaccine in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):465. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burhamah W, AlKhayyat A, Oroszlányová M, AlKenane A, Jafar H, Behbehani M, Almansouri A. The SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy among the general population: a large cross-sectional study from Kuwait. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Marshoudi S, Al-Balushi H, Al-Wahaibi A, Al-Khalili S, Al-Maani A, Al-Farsi N, Al-Jahwari A, Al-Habsi Z, Al-Shaibi M, Al-Msharfi M, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward the COVID-19 vaccine in Oman: a pre-campaign cross-sectional study. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):602. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asadi Faezi N, Gholizadeh P, Sanogo M, Oumarou A, Mohamed MN, Cissoko Y, Sow MS, Keita BS, Baye YA, Pagliano P, et al. Peoples’ attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine, acceptance, and social trust among African and Middle East countries. Health Promot Perspect. 2021;11(2):171–78. doi: 10.34172/hpp.2021.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Mistarehi AH, Kheirallah KA, Yassin A, Alomari S, Aledrisi MK, Bani Ata EM, Hammad NH, Khanfar AN, Ibnian AM, Khassawneh BY. Determinants of the willingness of the general population to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in a developing country. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2021;10(2):171–82. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2021.10.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hershan A. Awareness of COVID-19, protective measures and attitude towards vaccination among university of Jeddah health field community: a questionnaire-based study. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2021;15:604–612. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fayed AA, Al Shahrani AS, Almanea LT, Alsweed NI, Almarzoug LM, Almuwallad RI, Almugren WF. Willingness to receive the COVID-19 and seasonal influenza vaccines among the saudi population and vaccine uptake during the initial stage of the national vaccination campaign: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):765. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosental H, Shmueli L. Integrating health behavior theories to predict COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: differences between medical students and nursing students in Israel. medRxiv. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):783. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, Saef A. Vaccine hesitancy: beliefs and barriers associated with COVID‐19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J Med Virol. 2021;93(7):4280–91. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alfageeh EI, Alshareef N, Angawi K, Alhazmi F, Chirwa GC. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among the Saudi population. Vaccines. 2021;9(3):226. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abu-Farha RK, Alzoubi KH, Khabour OF. Public willingness to participate in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials: a study from Jordan. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:2451–58. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S284385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mejri N, Berrazega Y, Ouertani E, Rachdi H, Bohli M, Kochbati L, Boussen H. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: another challenge in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2021;30:289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Sanafi M, Sallam M. Psychological determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers in Kuwait: a cross-sectional study using the 5C and vaccine conspiracy beliefs scales. Vaccines. 2021;9(7):701. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9070701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.AlAwadhi E, Zein D, Mallallah F, Bin Haider N, Hossain A. Monitoring COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Kuwait during the pandemic: results from a national serial study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1413–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1657–63. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S276771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Qerem WA, Jarab AS. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and its associated factors among a Middle Eastern population. Front Public Health. 2021;9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.632914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Mulla R, Abu-Madi M, Talafha QM, Tayyem RF, Abdallah AM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative education sector population in Qatar. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):665. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Temsah MH, Barry M, Aljamaan F, Alhuzaimi A, Al-Eyadhy A, Saddik B, Alrabiaah A, Alsohime F, Alhaboob A, Alhasan K, et al. Adenovirus and RNA-based COVID-19 vaccines’ perceptions and acceptance among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia: a national survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e048586. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fares S, Elmnyer MM, Mohamed SS, Elsayed R. COVID-19 vaccination perception and attitude among healthcare workers in Egypt. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211013303. doi: 10.1177/21501327211013303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aloweidi, A, et al. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 Vaccines: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.El-Elimat, T, et al. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):p. e0250555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Halabi, C.K, et al. Attitudes of Lebanese adults regarding COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Public Health:2021. 21(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elharake, J.A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Health Care Workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis, 2021. 109:p. 286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green, M.S, et al. A study of ethnic, gender and educational differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Israel – implications for vaccination implementation policies. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 2021. 10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hammam, N, et al. Rheumatology university faculty opinion on coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) vaccines: the vaXurvey study from Egypt. Rheumatol Int, 2021. 41(9):p. 1607–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maraqa, B, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in Palestine: A call for action. Prev Med, 2021. 149:p. 106618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Omar, D.I. and Hani B.M., Attitudes and intentions towards COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors among Egyptian adults. J Infect Public Health. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palgi, Y, et al. No psychological vaccination: Vaccine hesitancy is associated with negative psychiatric outcomes among Israelis who received COVID-19 vaccination. J Affect Disord, 2021. 287:p. 352–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qattan, A.M.N, et al. Acceptability of a COVID-19 Vaccine Among Healthcare Workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front Med (Lausanne), 2021. 8:p. 644300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qunaibi, E, et al. Hesitancy of arab healthcare workers towards covid-19 vaccination: A large-scale multinational study. Vaccines, 2021. 9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rabi, R.et al, , Factors affecting nurses' intention to accept the COVID-19 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nurs. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors stated that all information provided in this article could be shared