Abstract

Objectives:

While mortality rates after burn are low, physical and psychosocial impairments are common. Clinical research is focusing on reducing morbidity and optimizing quality of life. This study examines self-reported Satisfaction With Life Scale scores in a longitudinal, multicenter cohort of survivors of major burns. Risk factors associated with Satisfaction With Life Scale scores are identified.

Methods:

Data from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) Burn Model System (BMS) database for burn survivors greater than 9 years of age, from 1994 to 2014, were analyzed. Demographic and medical data were collected on each subject. The primary outcome measures were the individual items and total Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) scores at time of hospital discharge (pre-burn recall period) and 6, 12, and 24 months after burn. The SWLS is a validated 5-item instrument with items rated on a 1–7 Likert scale. The differences in scores over time were determined and scores for burn survivors were also compared to a non-burn, healthy population. Step-wise regression analysis was performed to determine predictors of SWLS scores at different time intervals.

Results:

The SWLS was completed at time of discharge (1129 patients), 6 months after burn (1231 patients), 12 months after burn (1123 patients), and 24 months after burn (959 patients). There were no statistically significant differences between these groups in terms of medical or injury demographics. The majority of the population was Caucasian (62.9%) and male (72.6%), with a mean TBSA burned of 22.3%. Mean total SWLS scores for burn survivors were unchanged and significantly below that of a non-burn population at all examined time points after burn. Although the mean SWLS score was unchanged over time, a large number of subjects demonstrated improvement or decrement of at least one SWLS category. Gender, TBSA burned, LOS, and school status were associated with SWLS scores at 6 months; scores at 12 months were associated with LOS, school status, and amputation; scores at 24 months were associated with LOS, school status, and drug abuse.

Conclusions:

In this large, longitudinal, multicenter cohort of burn survivors, satisfaction with life after burn was consistently lower than that of non-burn norms. Furthermore mean SWLS scores did not improve over the two-year follow-up period. This study demonstrates the need for continued efforts to improve patient-centered long term satisfaction with life after burn.

Keywords: Burn, Satisfaction with life, Outcome

1. Introduction

Over the past four decades, mortality rates due to burn have decreased significantly [1–3]. Major advancements in burn care have included improvements in resuscitation and ventilation strategies; control of infection, including early excision and burn wound closure; as well as increased support of the hypermetabolic response to trauma. Given these improved survival rates, even more emphasis is now placed on measuring and optimizing the quality of life for burn survivors.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a metric created to better quantify a person’s general quality of life and global satisfaction [4]. The scale was originally validated using a healthy undergraduate student and elderly population, but later expanded to various patient populations, including those with spinal cord injury (SCI) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) [5,6]. It has since been translated into over five different languages and has demonstrated validity and reliability in a variety of populations [7,8]. Furthermore, SWLS is negatively correlated with other clinical measurements of distress [9,10]. The simple five question survey allows a respondent to rate a series of statements implicating their contentment with their current life.

Patterson et al. were the first to utilize the SWLS to investigate global satisfaction in burn survivors. They examined 295 burn survivors treated at 3 major U.S. burn centers and demonstrated that burn survivors had lower SWLS scores at 6 months after injury when compared to a non-burned population [11]. Using stepwise regression analysis they also showed that satisfaction with life at follow-up was best predicted by a combination of psychosocial and medical variables. By utilizing the Burn Injury Model System National Database, which has collected SWLS scores for the past 20 years, this study aims to confirm and expand upon Patterson’s findings. Here we evaluate SWLS scores in a large, multi-centered population of burn survivors over a 2 year follow-up period. Furthermore we identify predictors of SWLS scores in order to facilitate early recognition of these individuals for potential early interventions and increased support.

2. Materials and methods

Prospectively collected data from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) Burn Model System (BMS) database, for burn survivors from 1994 to 2014, were analyzed. A total of six centers have contributed to the database over this time period (Boston-Harvard Burn Injury Model System, Boston, MA; Northwest Regional Burn Model System, Seattle, WA; North Texas Burn Rehabilitation Model System, Dallas, TX; Pediatric Burn Injury Rehabilitation Model System, Galveston, TX; University of Colorado, Denver, CO; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). All patients greater than 9 years of age were included in the analysis. The NIDILRR BMS database comprises patients that meet at least one of the following current inclusion criteria:

Burn greater than or equal to 10% TBSA which underwent surgery for at least some portion of wound closure (defined as autografting); ages 65 years and older.

Burn greater than or equal to 20% TBSA which underwent surgery for at least some portion of wound closure; ages 0 years to 64 years old.

Electrical high voltage/lightning injury which underwent surgery for at least some portion of wound closure.

Burn of any size to critical area(s): face and/or hands and/or feet and/or genitals which underwent surgery for at least some portion of wound closure.

Since 1993, when the NIDILRR BMS database came into existence, minor modifications have been made to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. These modifications can be found at http://burndata.washington.edu/standard-operating-procedures and the complete detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously described [12]. Primary outcome measures include individual item and total SWLS scores. Demographic (age, gender, ethnicity, school/work status, and history of drug or alcohol abuse) and medical data were collected. Medical data included TBSA burned and grafted, length of stay (LOS), length of stay in ICU (ICU days), amputation, and heterotopic ossification (HO) at discharge or at follow-up. Data obtained at discharge, 6, 12, and 24 months after burn were extracted from the BMS national database and analyzed. If demographic data cannot be collected via patient report, it is collected from the medical record.

2.1. Outcome measures

The SWLS is a validated general psychometric tool used to assess a patient’s quality of life [5–9]. The questionnaire consists of 5 items rated on a 1–7 Likert scale (Fig. 1). SWLS scores were obtained at discharge, 6, 12, and 24 months after burn. SWLS scores at the time of discharge represent pre-burn scores, as patients were asked to recall their life four weeks before their burn and answer the questions accordingly. The higher the score, the greater life satisfaction one has.

Fig. 1 –

Satisfaction with Life Scale. Below are five statements that you may agree or disagree with. Using the 1–7 scale below, indicate your agreement with each. Please be open and honest in your responding.

2.2. Statistical analysis

STATA SE version 13 was used for the analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize medical and demographic variables of the study population. t-Tests were used to determine the differences between the means of medical and demographics variables, as well as mean SWLS scores at all time points and for the individual questions comprising the SWLS. The mean total SWLS score for a non-burn population has been previously calculated and described [7]. These mean total SWLS scores were compared to the computed normal SWLS score from Patterson’s study (23.94, SD 6.10). Unpaired t-tests were used to compare computed normalized values against the mean SWLS scores in this population of burn survivors for each consecutive time point and between each time point. Linear stepwise regression analyses were used to identify predictors of SWLS scores at each time point, with the first model including all hypothesized predictors of SWLS: age; gender; ethnicity; TBSA burned; TBSA grafted; ICU length of stay; hospital length of stay; amputation; heterotopic ossification at discharge; heterotopic ossification at follow-up; school status; employment; drug abuse; alcohol abuse; presence of physical disability; psychiatric treatment; and location of burn, head/neck vs. all other areas. For each time point, the final regression model included only those variables that were significant in the first model. A p-value of 0.05 was used for statistical significance.

3. Results

The demographic and medical data of the study population at each time point are presented in Table 1. The SWLS was completed at time of discharge (1129 subjects), 6 months after burn (1231 subjects), 12 months after burn (1123 subjects), and 24 months after burn (959 subjects). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at each follow-up except for length of stay (discharge to 6 month comparison only). Table 2 demonstrates mean total and mean individual SWLS scores at each follow-up time point. The mean total SWLS score obtained at discharge, representative of pre-burn, was significantly higher than that of a non-burn population(23.94 vs. 25.0, p < 0.000). The mean total SWLS scores obtained after burn, at all follow-up time points, were significantly lower than that of a non-burn population (23.94 vs. 21.0 (6 month), 21.5 (12 month), and 21.9 (24 month), p < 0.0000 for all time points).

Table 1 –

Descriptive statistics for patient population.

| Discharge | 6 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 40.1 (10.0–89.5) | 40.1 (10.0–86.2) | 39.8 (10.0–89.5) | 39.7 (10.0–88.2) |

| Gender | 71.9 (812) | 73.8 (908) | 72.0 (808) | 72.5 (695) |

| Male, % (N) | ||||

| Ethnicity, % (N) | ||||

| Caucasian | 60.1 (679) | 64.9 (799) | 63.7 (715) | 62.9 (603) |

| African-American | 14.6 (165) | 15.0 (185) | 14.8 (166) | 15.3 (147) |

| Hispanic | 19.3 (218) | 15.4 (189) | 17.0 (191) | 17.8 (171) |

| Asian | 1.2 (14) | 1.0 (12) | 1.1 (12) | 1.0 (10) |

| Other | 4.6 (53) | 3.8 (46) | 3.5 (39) | 2.9 (28) |

| Mean % TBSA burned (range) | 22.3 (0.01–95.0) | 21.9 (0–95.0) | 22.9 (0–95.0) | 22.1 (0–95.0) |

| Mean % TBSA grafted (range) | 13.5 (0–91.0) | 12.8 (0–91.0) | 13.6 (0–91.0) | 13.1 (0–91.0) |

| Mean LOS (range) | 33.1 (1–693) | 29.4 (1–257) | 32.9 (1–693) | 31.5 (1–693) |

| Mean ICU days (range) | 4.6 (0–18) | 8.7 (0–75) | 10 (0–106) | 8.5 (0–132) |

| Amputation, % (N) | 7.9 (89) | 7.9 (93) | 7.9 (85) | 6.7 (60) |

| HO at discharge, % (N) | 5.7 (58) | 4.8 (51) | 6.4 (61) | 5.7 (46) |

| In school, % (N) | 18.3 (205) | 15.5 (189) | 16.4 (182) | 18.0 (169) |

| Employment status, % (N) | ||||

| Working | 64.6 (636) | 68.1(746) | 68.9 (679) | 68.5 (568) |

| Not working | 23.7 (233) | 20.9 (229) | 19.9 (196) | 18.9 (157) |

| Other | 11.7 (115) | 11.1 (121) | 11.1 (110) | 12.6 (104) |

| History of alcohol abuse, % (N) | 12.1 (136) | 10.7 (131) | 10.0 (111) | 9.3 (88) |

| History of drug abuse, % (N) | 9.9 (111) | 8.4 (102) | 7.9 (88) | 6.3 (60) |

Note: No statistically significant differences between the groups were note for each follow-up except for length of stay, discharge to 6 month comparison only.

Table 2 –

Mean SWL, total and individual item scores, at each time point following burn.

| Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharge (n = 1129) | 6 Months (n = 1231) | 12 Months (n = 1123) | 24 Months (n = 959) | |

| Total SWL score | 25.0 (7.8) | 21.0 (8.3) | 21.5 (8.6) | 21.9 (8.4) |

| SL1. In most ways my life is close to ideal | 5.0 (1.9) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| SL2. The conditions of my life are excellent | 5.0 (1.9) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.0,) |

| SL3. I am satisfied with my life | 5.3 (1.7) | 4.4 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.7 (1.9) |

| SL4. So far I have gotten the important things I want in life | 5.0 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.7 (1.9) | 4.8 (1.9) |

| SL5. If I could live my life over I would change almost nothing | 3.9 (2.1) | 4.0 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.1) | 4.0 (2.1) |

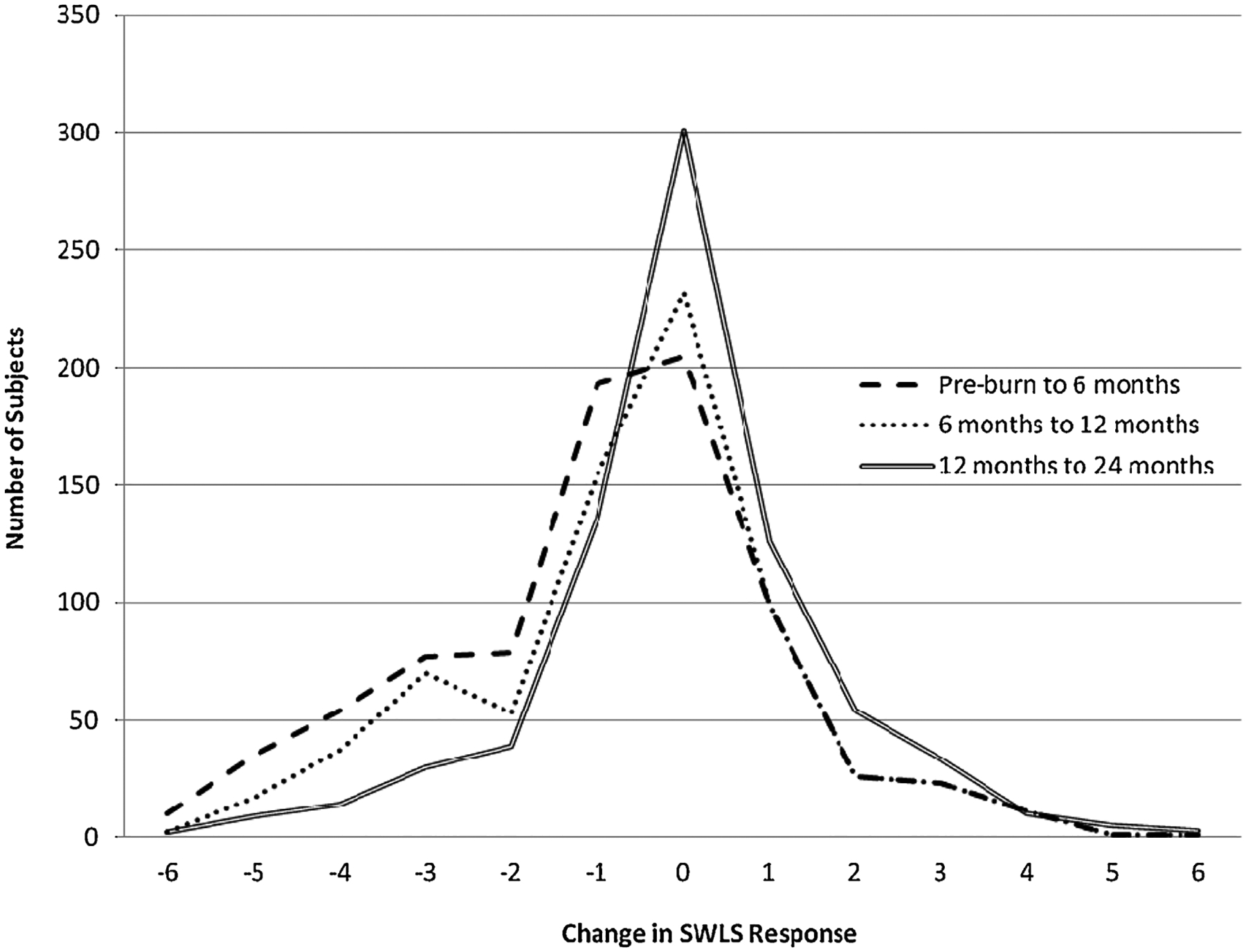

Table 3 demonstrates p-values for the comparisons of mean total and individual SWLS scores at all time points. Mean total SWLS scores at all follow-up time points were significantly lower than those at discharge (i.e. pre-burn), additionally total scores did not significantly change over the 2 year follow-up time course. Of the individual questions, SL1 (“In most ways my life is close to ideal”) and SL2 (“the conditions of my life are excellent”) demonstrated very small, but statistically significant improvement between 6 and 12 months but not between 12 and 24 months. Consistent with mean SWLS, questions SL3, 4 and 5 showed no significant recovery at any time point after burn. Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of patient SWLS scores and demonstrates the greater variability in responses from discharge to 6 months, but with eventual consistency and centralization closer to the mean between 6 months to 12 months and 12 months to 24 months. A number of individual subjects demonstrated an increase (pre-injury to 6 months: 161; 6 months to 12 months: 161; 12 months to 24 months: 231) and a decrease (pre-injury to 6 months: 448; 6 months to 12 months: 334; 12 months to 24 months: 230) in total SWLS scores at consecutive time points.

Table 3 –

Comparison of mean SWL, total and individual scores, at each time point.

| Pre-burn and 6 months | Pre-burn and 12 months | Pre-burn and 24 months | 6 months and 12 months | 6 months and 24 months | 12 months and 24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.0000 | p = 0.0844 | p = 0.1198 | p = 0.3625 |

| SL1. In most ways my life is close to ideal | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.0000 | p = 0.0042 | p = 0.0028 | p = 0.4376 |

| SL2. The conditions of my life are excellent | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.0000 | p = 0.0015 | p = 0.2057 | p = 0.7648 |

| SL3. I am satisfied with my life | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.0000 | p = 0.0816 | p = 0.1649 | p = 0.2602 |

| SL4. So far I have gotten the important things I want in life | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.0131 | p = 0.8139 | p = 0.4484 | p = 0.7110 |

| SL5. If I could live my life over I would change almost nothing | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.0000 | p = 0.1077 | p = 0.5858 | p = 0.5267 |

Note: The values in italic denote significance.

Fig. 2 –

Distribution of Patient Satisfaction with Life Scale Scores.

Table 4 shows the final regression model. Increased length of stay and enrollment in school were the only two variables associated with lower SWLS score at all time points. Whereby a one unit increase in length of hospital stay was associated with a 0.07, 0.04, or 0.02 unit decrease in predicted SWLS score at 6,12 or 24 months, respectively. Similarly, not attending school was associated with a 2.65, 2.13, or 2.42 unit decrease in predicted SWLS score at 6,12 or 24 months, respectively. Additionally, female gender and larger TBSA burned were associated with predictably lower SWLS scores at 6 months, amputation at 12 months, and history of drug abuse at 24 months (p < 0.05).

Table 4 –

Regression models with total SWL score as dependent variable.

| Predictor | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | β | SE | t | p-Value | Coefficient | β | SE | t | p-Value | Coefficient | β | SE | t | p-Value | |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.80 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −1.34 | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.93 | 0.35 |

| Gender | −1.2 | −0.06 | 0.54 | −2.22 | 0.03 | −0.88 | −0.05 | 0.59 | −1.50 | 0.14 | −0.94 | −0.05 | 0.62 | −1.53 | 0.13 |

| TBSA burned | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 2.56 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.72 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.81 | 0.42 |

| LOS | −0.07 | −0.21 | 0.01 | −5.99 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.01 | −4.60 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.09 | 0.01 | −2.34 | 0.02 |

| School | −2.65 | −0.12 | 0.74 | −3.60 | 0.00 | −2.13 | −0.09 | 0.81 | −2.60 | 0.01 | −2.42 | −0.11 | 0.82 | −2.93 | 0.00 |

| Alcohol abuse | −0.29 | −0.04 | 0.20 | −1.41 | 0.16 | ||||||||||

| Psychiatric treatment | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 1.24 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 1.53 | 0.13 | |||||

| TBSA grafted | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.59 | ||||||||||

| Drug abuse | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 2.23 | 0.03 | ||||||||||

| Amputation | 2.64 | 0.08 | 1.00 | 2.64 | 0.01 | ||||||||||

Notes: The values in italic denote significance.

Alcohol abuse, psychiatric treatment, drug abuse = previous history.

School = enrollment in school.

Gender = female.

4. Discussion

This analysis represents the largest review of satisfaction with life after burn to date, and includes follow-up for up to 2 years. The majority of psychosocial, burn-related research has focused on psychopathology associated with burn-injury, for example post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety [13–19]. More recently after burn quality of life has been investigated, although the data is not robust; and with respect to satisfaction with life after burn [20–24], only one study has previously examined this outcome [11].

Full physical and psychological recovery after a burn can be a daunting task for survivors. Physically survivors face significant obstacles, including functional deficits, chronic pain, pruritus, and disfigurement. In addition to the physical obstacles, psychosocial factors include post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and other stressors, such as returning to work or school (impairment in community reintegration). In recent years, with increasing focus on long-term psychosocial outcomes, metrics such as the Young Adult Burn Questionnaire (YABOQ) and Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ) have been increasingly used in burn populations to gauge progress and recovery with respect to quality of life variables after injury [25–29]. Along these lines, the NIDILRR BMS longitudinal national database is the only U.S. national database specifically collecting information on the long term physical and psychosocial outcomes of burn survivors. The value of this study lies, in part, with the richness of this database. In particular, the Satisfaction with Life Scale has been the most consistently measured variable in the database, having been collected for approximately 20 years [12].

Patterson et al. were the first to report the SWLS in the burn population. They examined SWLS scores at discharge and at 6 month follow-up in 295 burn survivors from three major U.S. burn centers. The current study builds on these results in that it includes data on up to 1231 patients from 6 major U.S. burn centers, and includes SWLS for discharge, 6 months, 12 months and 24 month after injury. In this large population, we confirm Patterson’s findings that burn survivors report lower SWLS scores at 6 month follow-up when compared with non-burned individuals. We further demonstrate that this reduction in SWLS score remains lower than normalized controls for up to two years after injury and note the lack of statistically significant improvements between 6, 12, and 24 months.

Patterson et al. also determined predictors of SWLS at discharge and 6 months after injury. At discharge, they found lower SWLS scores to be associated with unmarried status, history of alcohol abuse, need for psychological treatment in the preceding year, and length of ICU stay. At 6 months, lower SWLS scores were associated with unmarried status, need for psychological treatment in the preceding year, length of ICU stay, and amputation as a result of the burn. While the predictors in our regression model were not identical, and marital status was not collected in this study; there were similarities, specifically indicating that both medical and psychosocial variables contribute to lowered SWLS scores. Although injury related factors, such as TBSA and amputation, are often not modifiable, increased efforts on community integration and psychosocial support for substance abuse has the potential to result in improvements in satisfaction with life. Community integration typically involves schooling, employment, relationships, leisure, and a variety of outside interests and lifestyles. In addition, a more detailed evaluation of the role of long term psychological rehabilitation for burn survivors is necessary.

A notable finding in the current study was that mean SWLS scores did not recover at anytime point during the two-year follow-up. Possibilities for this finding may be related to limitations with the study or with the SWLS instrument. It is conceivable that the SWLS was insufficiently sensitive to detect subtle changes over time or a follow-up period of two years may have been too short to detect such change. While it is possible that burn survivors may never regain their pre-injury SWL, it is also possible that complete psychological and emotional recovery takes a period of more than 2 years. In fact, with respect to depression, it has been shown that a significant number of burn survivors still reported symptoms of moderate to severe depression at 2 years after burn [30]. Studies investigating the quality of life and long term outcomes after burn have demonstrated recovery through three year follow-up periods and recommend long time frames for such evaluations [31]. In a recent study utilizing the Young Adult Burn Outcome Questionnaire (YABOQ), perceived appearance and social function limited by appearance remained below non-burn levels at 3-years after burn [32]. SWL may, therefore, recover at a slower rate than physical recovery and with this consideration, the BMS now includes additional time points: every 5 years after injury for the duration of the burn survivor’s lifetime. Lastly, although SWLS scores were significantly lower after burn, this study does not establish causality between the burn and one’s satisfaction with life score, nor does it ascertain whether this statistical difference was clinically significant. In either case, it warrants a more in-depth investigation into the direct basis for the lowered scores and their clinical relevance.

There are a number of additional limitations with this study. SWLS scores at the time of discharge represent pre-burn scores, as patients were asked to recall their life four weeks before their burn and answer the questions accordingly; as such, it is subject to recall bias. Furthermore, SWLS data is self-reported and therefore susceptible to reporting bias. The inclusion criteria for the NIDILRR BMS database is selective of those patients with more severe burns, has been modified slightly over the 20 years of its existence, and may not be representative of all burn patients and all burn centers. There are factors that could have influenced SWLS scores that were not captured by our database and included in our analysis, such as specific medical conditions and/or lifestyle factors. Furthermore over the past few decades, several new resources for burn survivors’ have emerged, most significantly the Phoenix Society. Efforts such as the World Burn Congress and local burn survivor support groups have provided a personalized and supportive context for burn patients and a sense of community. These organizations are an important reality of burn recovery today and their increasing popularity indicates the value of such community in rehabilitation. Inclusion and level of participation in such organizations and support groups was not factored into our analysis, however may have an impact on satisfaction with life.

In order to better understand the psychological and social recovery of burn, further investigations are needed. While no metric is perfect, the SWLS is a validated instrument and may provide useful insight into the multi-dimensional recovery of this patient population. Questions to be answered include: is the statistically significant reduction in the SWLS score at the two year follow-up clinically significant; does the SWLS return to that of the non-burned population if given more time, is there a positive correlation between the SWLS and community integration and/or participation in burn support groups; are there additional metrics the may be more sensitive to detect subtle changes in the life satisfaction of burn survivors; and lastly, what is the role of long term psychological rehabilitation in recovery from burns.

5. Conclusion

SWLS scores for burn survivors are significantly less than that of non-burned individuals and do not significantly improve from 6 months to 2 years after injury. SWLS scores were associated with both medical and psychosocial factors. Continued efforts to improve patient-centered long term satisfaction with life after burn are needed and will likely include emphasis on community integration.

Funding source

The contents of this manuscript were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DP0035). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

REFERENCES

- [1].Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, Sheridan RL, Tompkins RG. Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. NEJM 1998;338:362–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Muller MJ, Pegg SP, Rule MR. Determinants of death following burn injury. Br J Surg 2001;88:583–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tompkins RG. Survival from burns in the new millennium: 70 years experience from a single institution. Ann Surg 2015;261:263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985;49:71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Braden CA, Cuthbert JP, Brenner L, Hawley L, Morey C, Newman J, et al. Health and wellness characteristics of persons with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2012;26(11):1315–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shirom A, Toker S, Melamed S, Berliner S, Shapira I. Life and job satisfaction as predictors of the incidence of diabetes. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2012;4(March(1)):31–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Simpson PL, Schumaker JF, Dorahy MJ, Shrestha SN. Depression and life satisfaction in Nepal and Australia. J Soc Psychol 1996;136(December (6)):783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schumaker JF, Shea JD, Monfries MM, Groth-Marnat G. Loneliness and life satisfaction in Japan and Australia. J Psychol 1993;127(January (1)):65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pavot W, Diener ED, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Pers Assess 1991;57:149–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pavot W, Diener E. The affective and cognitive context of self-reported measures of subjective well-being. Soc Indic Res 1993;28:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Patterson DR, Ptacek JT, Cromes F, Fauerback JA, Engrav L. The 2000 clinical research award: describing and predicting distress and satisfaction with life for burn survivors. J Burn Care Res 2000;21:490–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Klein MB, Lezotte DL, Fauerbach JA, Herndon DN, Kowalske KJ, Carrougher GJ, et al. The National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research burn model system database: a tool for the multicenter study of the outcome of burn injury. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Attoe C, Pounds-Cornish E. Psychosocial adjustment following burns: an integrative literature review. Burns 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA. Personality, coping, chronic stress, social support and PTSD symptoms among adult burn survivors: a path analysis. J Burn Care Rehabil 2003;24(1):63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Andrews RM, Browne AL, Drummond PD, Wood FM. The impact of personality and coping on the development of depressive symptoms in adult burns survivors. Burns 2010;36:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ahrari F, Salehi SH, Fatemi MJ, Soltani M, Taghavi S, Samimi R. Severity of symptoms of depression among burned patients one week after injury, using beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II). Burns 2013;39:285–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Maghsoudi H, Soudmand-Niri M, Ranjbar F, Mashadi-Abdollahi H. Stress disorder and PTSD after burn injuries: a prospective study of predictors of PTSD at Sina Burn Center, Iran. J Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2011;7:425–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gould NF, McKibben JB, Hall R, Corry N, Amoyal NA, Mason ST, et al. Peritraumatic heart rate and posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with severe burns. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72(4):539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Van Loey NEE, Maas CJM, Faber AW, Taal LA. Predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress symptoms following burn injury: results of a longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress 2003;16(4):361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liang CY, Wang HJ, Yao KP, Pan HH, Wang KY. Predictors of health-care needs in discharged burn patients. Burns 2012;38:172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Orwelius L, Willebrand M, Gerdin B, Ekselius L, Fredrikson M, Sjoberg F. Long term health-related quality of life after burns is strongly dependent on pre-existing disease and psychosocial issues and less due to the burn itself. Burns 2013;39:229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Low AJ, Dyster-Aas J, Willebrand M, Ekselius L, Gerdin B. Psychiatric morbidity predicts perceived burn-specific health 1 year after a burn. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xie B, Xiao SC, Zhu SH, Xia ZF. Evaluation of long term health-related quality of life in extensive burns: a 12-year experience in a burn center. Burns 2012;38:348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ying LY, Pertrini MA, Xin LL. Gender differences in the quality of life and coping patterns after discharge in patients recovering from burns in China. J Res Nurs 2010;18(3):247–62. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ryan CM, Lee A, Kazis LE, Schneider JC, Shapiro GD, Sheridan RL, et al. Recovery trajectories after burn injury in young adults: does burn size matter? J Burn Care Res 2015;36(January–February (1)):118–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ryan CM, Lee AF, Kazis LE, Shapiro GD, Schneider JC, Goverman J, et al. Is real-time feedback of burn-specific patient-reported outcome measures in clinical settings practical and useful? A pilot study implementing the young adult burn outcome questionnaire. J Burn Care Res 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gerrard P, Kazis LE, Ryan CM, Shie VL, Holavanahalli R, Lee A, et al. Validation of the community integration questionnaire in the adult burn injury population. Qual Life Res 2015;24(November (11)):2651–5 [Epub 2015 May 19]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Marino ME, Bori MS, Rossi M, Amaya F, Schneider JC, Ryan CM, et al. Measuring the community re-integration of burn injuries in adults: conceptual foundation for future development of a computer adaptive test (CAT). J Qual Life Res 2014;23:141. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Marino M, Bori MS, Amaya F, Rossi M, Slavin M, Ryan CM, et al. Social participation of burn survivors: a conceptual framework. J Burn Care Res 2015;36:S97. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wiechman SA, Ptacek JT, Patterson DR, Gibran NS, Engrav LE, Heimbach DM. Rates, trends, and severity of depression after burn injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22(November–December (6)):417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Renneberg B, Ripper S, Schulze J, Seehausen A, Weiler M, Wind G, et al. Quality of life and predictors of long-term outcome after severe burn injury. J Behav Med 2014;37(October (5)):967–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ryan CM, Lee A, Kazis LE, Schneider JC, Shapiro GD, Sheridan RL, et al. Recovery trajectories after burn injury in young adults: does burn size matter? J Burn Care Res 2015;36(January–February (1)):118–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]