Abstract

Background:

A 2019 public workshop convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) Roundtable on Health Literacy identified a need to develop evidence-based guidance for best practices for health literacy and patient activation in clinical trials.

Purpose:

To identify studies of health literacy interventions within medical care or clinical trial settings that were associated with improved measures of health literacy or patient activation, to help inform best practices in the clinical trial process.

Data sources:

Literature searches were conducted in PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, SCOPUS, Cochrane, and Web of Science from January 2009 to June 2021.

Study selection:

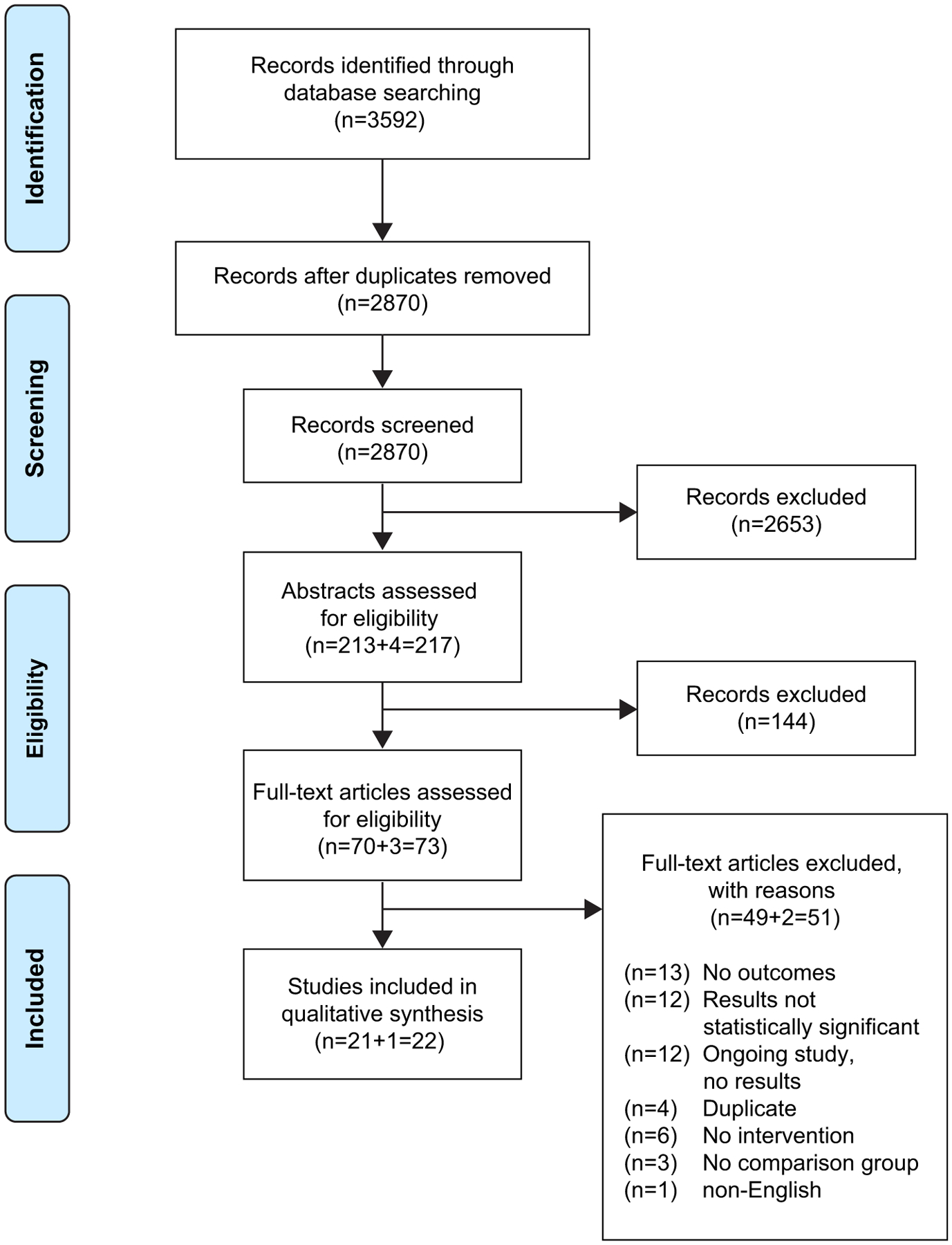

Of 3592 records screened, 22 records investigating 27 unique health literacy interventions in randomized controlled studies were included for qualitative synthesis.

Data extraction:

Data screening and abstraction were performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Data synthesis:

Types of health literacy interventions were multimedia or technology-based (11 studies), simplification of written material (six studies) and in-person sessions (five studies). These interventions were applied at various stages in the healthcare and clinical trial process. All studies used unique outcome measures, including patient comprehension, quality of informed consent, and patient activation and engagement.

Conclusions:

The findings of our study suggest that best practice guidelines recommend health literacy interventions during the clinical trial process, presentation of information in multiple forms, involvement of patients in information optimization, and improved standardization in health literacy outcome measures.

Keywords: Health literacy, Systematic literature review, Clinical trial process, Patient-centered, Qualitative synthesis

1. Introduction

The Healthy People 2030 Initiative and the National Institutes of Health define health literacy as having two components: personal health literacy and organizational health literacy. Personal health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others;” organizational health literacy is “the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” [1,2]. This two-part definition emphasizes that health literacy is not only a characteristic of an individual, but it is also the responsibility of organizations to make their materials accessible and understandable to their intended audience.

People may be at a higher risk for low health literacy if they are older, are from a diverse racial or ethnic background, have a lower level of education, live below the poverty level, spoke a language other than English before starting school, or are stressed from a recent diagnosis of a disease or illness [3–5]. People with low health literacy are more likely to have poorer health outcomes, make medication errors, have difficulty managing chronic diseases, and skip preventive health services [6]. Therefore, it is imperative for organizations to embed health literacy principles into clinical research materials to foster patient understanding and the ability to make informed health choices. Moreover, people of diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds are often under-represented in clinical trials. Therefore organizations that implement health literacy interventions to overcome barriers to participation for these people could benefit from more representative trial populations [7], and more accurate trial data from participants who understand and are better able to follow treatment and monitoring schedules [5].

Although health literacy is an important consideration in clinical trial design, incorporation of health literacy best practices into clinical trials is often limited and inconsistent. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) Roundtable on Health Literacy [8] convened a public workshop in 2019 featuring expert presentations and discussions on how health literacy principles are being incorporated into clinical trials [5]. Strategies discussed included using plain language in consent materials, using consistent language across the clinical trial process, limiting tables, and use of percentages and probabilities, having the target audience review the materials, and communicating basic points slowly using iterative “teach back” to confirm adequate understanding [5]. These strategies can be applied to all types of informational material used by patients, including material created for the clinical trial investigators and healthcare providers to use with patients (called ‘patient-facing content’). Patient decision aids have also been found to increase comprehension and informed choice [9], and delivering content using multiple strategies has been shown to improve participant understanding of key components and awareness of the responsibility involved with participation [10]. One of the key outcomes from the NASEM workshop was the need to develop evidence-based guidance for best practices for health literacy and patient activation in clinical trials.

Building on recommendations from the NASEM workshop, this systematic review aims to identify randomized studies of health literacy interventions within medical care or clinical trial settings that were associated with improved measures of health literacy or patient activation, to help inform best practices in the clinical trial process. This review focuses on database searches using search terms agreed in consultation with members of the NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy [8]. Health literacy interventions shown to improve health literacy or patient activation could inform the development of evidence-based best practice guidelines for the clinical trial process, ultimately leading to a more patient-centered approach and improved outcomes for patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. Although this review protocol was not registered, existing registered protocols with PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) were checked at the time of this writing to ensure that no such review has been registered.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Randomized clinical studies of health literacy interventions that demonstrated improvements in health literacy or related outcomes that were published between January 2009 and June 2021 were considered in the search. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were agreed upon by members of the NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy (Table 1). The search for clinical studies was global, with no geographical restrictions or focus, and interventions at both the population and individual levels were considered. Studies with only a case report or observational data and research studies in progress that did not report results were excluded. Studies that measured outcomes in relation to health literacy, such as patient activation and decision-making, were also included.

Table 1.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Trial arm incorporating one or more health literacy interventions when using patient-facing content in healthcare or in a clinical trial | No intervention or comparison group Study in progress that does not report results |

| Published between January 2009 and June 2021 | Not a randomized clinical trial Results not statistically significant |

| Study design containing randomized clinical trials and/or quasi-randomized clinical trials | Incorporated pediatric participants |

2.3. Information sources

The search was conducted using the following databases: PubMed, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), SCOPUS, Cochrane, and Web of Science to find eligible studies published in English. The search was initially conducted in September 2019 and repeated in June 2021 to capture recent studies published during the development of this paper.

2.4. Search

Selected keywords for the search were agreed upon by members of the NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy and included health literacy, clinical trial, and plain language, and are presented in Appendix 1. The operators “OR” and “AND” were used for combinations of keywords. Search terms were the same for all databases.

2.5. Study selection

The study selection was completed by two researchers (MB and LZ) trained in the PRISMA method. All records identified from the databases were pooled together. Duplicate articles and those that did not meet the search criteria were removed. The two reviewers independently completed the title-abstract screening and reviewed all selected abstracts to determine the eligible papers for final full-text screening. Articles were included for further review if the following eligibility criteria were met: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal, (2) inclusion of a patient health literacy assessment as an outcome of an intervention or patient-facing content, (3) published between January 2009 to June 2021, and (4) English text. Articles were excluded only if both reviewers reached agreement after individually reviewing the articles based on the criteria provided. If consensus was not achieved, the abstract was included for full-text review. Both reviewers independently assessed the full texts for selecting the final set of papers for qualitative synthesis. Final exclusion process centered on study designs; those studies that did not examine outcomes related to health literacy, did not report a significant improvement in the health literacy outcome, or were not completed or in progress and did not report results were excluded. Since the objective was to identify studies that demonstrated improvements in health literacy or related outcomes, studies reporting a significant reduction in health literacy or no significant change in health literacy were excluded. Studies reporting p values were included if p < 0.05. Studies reporting other measures of significance were included if they met the significance threshold reported in the article. A third researcher (DR) resolved any conflicts during the final full-text review. The final set of studies selected for qualitative synthesis was reviewed by the research team.

2.6. Screening process

Data screening and extraction processes were conducted by two reviewers using Covidence for Cochrane Reviews [12]. Articles for final review were imported to this software platform to streamline full-text analysis process, including assessing risk of bias and extracting study characteristics and outcome [13]. Data screening involved the use of a standard electronic form on Covidence in order to screen references by either selecting “yes”, “maybe” or “no” based on the criteria described above. A further review allowed reviewers to identify the specific reasons for exclusion and inclusion of full texts. The rationale for exclusions on the form included study design, population, outcomes, and intervention. Conflicts were resolved between both reviewers and consensus achieved for all final texts. Final data extraction for qualitative synthesis was conducted by two reviewers. Extracted data was reviewed by the third researcher for accuracy.

2.7. Data extraction

The data extraction included collecting data on relevant study characteristics. These variables included author, year, country, study design (type of randomized clinical trial), health literacy intervention, population (including demographic characteristics of interest such as age, race, and sex), and outcome of interest. Other variables included the health literacy measurement used in the study; comparison group; relevant details about the control group; study results, including relevant statistically significant findings; and primary conclusions of the studies.

2.8. Risk of bias in individual studies

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Comparison tool (RoB2) [14] was implemented through a standardized form by the two reviewers. The RoB2 tool assessed several domains of bias, including sequence of generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors for all outcomes, incomplete outcome data for all outcomes, selective outcome reporting, and any other general sources of bias. To ensure quality control, the two reviewers independently made the assessments. Studies rated as having a high risk of bias were noted but included due to limited studies available, and any conflicts were discussed thoroughly and resolved.

Risk of reporting bias was assessed by screening the abstracts of studies excluded for lack of statistical significance, to determine whether any of these studies assessed the same intervention as one of the included studies.

2.9. Synthesis of results

A qualitative synthesis was performed, with studies categorized by the type of intervention: (1) simplification of written material, (2) inclusion of multimedia or technology-based approaches, or (3) facilitation of in-person sessions. If a study included multiple interventions of the same type, the study was placed into the relevant type category. If a study contained multiple interventions of multiple types, the study was placed into the multimedia category. All relevant summary measures were extracted from the studies.

3. Results

Of the 3592 records screened, 22 records were included for final qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1). Most records (n = 15/22) were identified as having a low risk of bias in all domains (Table 2). Eleven studies were based in the United States, and the remaining 11 studies were based in 11 different countries (Table 3). Many studies (n = 6) required participants to be able to speak and/or read English, four required participants to speak and/or read in one or more languages other than English, and five required participants to speak and/or read English and/or another language. From the 22 included studies, 27 unique clinical trial interventions were identified (three studies looked at multiple interventions and three studies looked at the same intervention).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram.

Table 2.

Risk of Bias Summary.

| Author, year [ref#] | Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding Participants and Personnel | Blinding Outcome Assessors | Incomplete Outcomes Data | Selective Outcomes Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addissie, 2016 [29] | ||||||

| Afolabi, 2015 [22] | ||||||

| Baker, 2014 [24] | ||||||

| Benatar, 2012 [26] | ||||||

| Blancafort Alias, 2021 [36] | ||||||

| Caroll, 2019 [35] | ||||||

| Cegala, 2013 [31] | ||||||

| Chalela, 2018 [21] | ||||||

| Fink, 2010 [23] | ||||||

| Han, 2017 [34] | ||||||

| Jibaja-Weiss, 2011 [25] | ||||||

| Kim EJ, Kim SH, 2015 [27] | ||||||

| Koonrungsesomboon, 2016 [28] | ||||||

| Kuppermann, 2014 [20] | ||||||

| Piette, 2016 [17] | ||||||

| Poureslami, 2012 [19] | ||||||

| Reder, Kolip, 2017 [30] | ||||||

| Roter, 2015 [18] | ||||||

| Smith, 2010 [16] | ||||||

| Solhi, 2019 [33] | ||||||

| Street Jr, 2010 [32] | ||||||

| Tait, 2009 [15] |

Risk of bias: Low  , High

, High  , Unclear

, Unclear

Table 3.

Evidence summary.

| Author, Year [ref #] | Country | Intervention | Population | Outcome of Interest and Measurement | Results | Primary Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Subtype: simplification of written material | ||||||

| Addissie, 2016a[29] | Ethiopia | Rapid Ethical Assessment (REA) | Pregnant women (age 18–45y) attending antenatal care follow-up in 4 health facilities, and were targeted for HPV sero-prevalence study n = 300 | Comprehension, retention, and quality of informed consent process by MICCA, retention rate, and QuIC, respectively | Comprehension score, mean diff: 27.9% (95% CI 24.0–33.4%; p < 0.001 Retention rate vs control: 85.7% and 70.3% (p < 0.005) QuIC, mean score, intervention vs control: 89.1% vs 78.5%; mean diff 10.5% (95% CI 6.8–14.2%; p < 0.001). |

Informed consent comprehension, quality of the consent process, study recruitment, and retention rates significantly improved in REA group |

| Benatar, 2012 [26] | New Zealand | Short or simplified ICF & booklet | Hospital in-pts from 8 wards of various specialties; age ≥ 18y, able to read English, not incapacitated, and not expected to be discharged within 3 h n = 282 | Pt comprehension, pt rights by questionnaire | Comprehension assessed for in-pts was better for booklet and short ICF: 62% (95% CI 56–67) correct, or simplified ICF 62% (CI 58–68) correct vs 52%, (CI 47–57) correct for standard ICF, p = 0.009 Pt rights correct responses - standard ICF: 49% (CI 43–55) vs with short ICF: 64% (CI 60–66, p = 0.0003), or vs simplified ICF: 61% (CI 59–63, p = 0.02) |

A booklet can provide information on pt rights and improve comprehension |

| Cegala, 2013 [31] | United States | PACE booklet (detailed information about condition, asking questions, checking and expressing concerns) | Parents who brought child for initial surgical consultation n = 65 | Pt (parents) participation in surgical consultation for their child by postinterview questionnaire Consultation encounters were recorded for review | Parents spent avg. 26.4 min with PACE booklet (range, 10–60 min [SD 14.90]). Avg. 8.55 (SD 2.41) on 10-point scale to evaluate usefulness (not at all to extremely) Parents who received the PACE booklet participated significantly more than control parents (p < 0.005) |

PACE booklet promoted parent participation in medical consult; had great impact on questions asked by parents Outcomes suggest parents found PACE useful and spent reasonable time to review it |

| Kim EJ, Kim SH, 2015 [27] | Korea | Standard or simplified ICF for cancer clin trial Simplified ICF used plain language, short sentences, diagrams, pictures, and bullet points | Main family caregivers of cancer pts, age ≥ 18y not participating in clin trials, can read and understand Korean n = 150 | Understanding, efficacy of informed consents by QuIC and Korean Test of Functional Health Literacy | Participants using simplified form displayed significantly higher levels of objective and subjective understanding relative to those using standard form (F = 10.8, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07; and F = 13.75, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09) No interaction found between type of consent form and health literacy level for understanding |

Understanding in pts with lower health literacy levels remained poorer vs higher literacy levels, even with simplified ICF; but the simplified ICF was effective in enhancing subjective and objective understanding irrespective of health literacy level |

| Koonrungsesomboon, 2016b [28] | Thailand | Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER) ICF | Volunteers (age > 18y) able to read and write Thai, who had time to read the entire ICF and do the post-test questionnaire were recruited from universities, colleges, cafeterias, hospitals, and markets in Chiang Mai n = 550 | Compare understanding of enhanced ICF vs conventional ICF by post-test questionnaire of 21 short case studies that showed common practical situation followed by a 3- answer multiple-choice question | The proportion of participants who achieved a post-test score of >80% was significantly higher for the enhanced ICF group vs the conventional ICF group (82.2% vs 60.4%, p < 0.001) Time spent by participants in enhanced ICF group was significantly less vs conventional ICF group (20 vs 25 min, p < 0.001) Total score of post-test and score of each category in enhanced ICF group were significantly higher vs conventional ICF group (19 vs. 18, p < 0.001) |

First study demonstrating the applicability and effectiveness of the SIDCER ICF through a randomized-controlled design It is possible to shorten the ICF while retaining all essential elements SIDCER ICF template is applicable to a clin PK study and is effective for this population group |

| Reder and Kolip, 2017 [30] | Germany | Decision aid for women; included additional information, pictograms, and clarification exercise | Age 50y (birth mo: March to May 1964), from registration office from Westphalia-Lippe, with a potential Turkish migration background n = 1206 | Informed choice decision-making (for mammogram) by questionnaires, decisional conflict using the 4-item SURE test, and decisional regret using the Decision Regret Scale | Women in the control group had lower odds of making an informed choice vs the decision aid group at post intervention (OR 0.26, CI 0.018–0.37, p < 0.001) and follow-up (OR 0.66, CI 0.46–0.94, p = 0.024) Women in decision aid group had significantly greater knowledge (second assessment p = 0.01; third assessment p = 0.034), and less decisional conflict (second assessment p < 0.001; third assessment p = 0.042) |

Decision aid was effective in improving the rate of informed choice |

| Intervention Subtype: multimedia or technology-based | ||||||

| Afolabi, 2015 [22] | Gambia | Multimedia Consent Tool | Age ≥ 18y, speak and understand 1 of 3 major Gambian languages (Mandinka, Fula, or Wolof) and no obvious communication, visual, or cognitive impairment Individuals are research participants in a malaria treatment trial n = 311 | Comprehension, retention of consent information by computerized, audio, informed consent comprehension questionnaire, NVivo v10 used to analyze audio recordings | At all study assessments, intervention vs control group achieved significantly higher consent comprehension scores Comprehension score on day of intervention (day 0), median: 64% vs 40%, intervention vs control (p = 0.042) Time to comprehension score reduction to <50%: 67 vs 40.6 days, intervention vs control (p < 0.0001) |

Use of multimedia tool significantly improved participant understanding of clin trial information and provided longer retainment of study information |

| Fink, 2010 [23] | United States | iMedConsent program with an additional module (RB) | Veterans who spoke English, were competent to give informed consent, did not have severe psychiatric illness, no ongoing substance abuse, and were scheduled for 1 of 4 surgeries: carotid endarterectomy (CEA), laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), radical prostatectomy (RP), and total hip arthroplasty (THA) n = 575 | 5 primary outcome measures: pt comprehension of the surgery, pt satisfaction with decision-making, pt satisfaction with healthcare, pt anxiety about the surgery, and provider use and satisfaction with iMedConsent (with or without RB), measured by customized questionnaires | Significant improvement in total mean comprehension scores for all surgeries with RB vs no RB: 71.4% vs 68.2% correct, p = 0.03. Effect was greatest in CEA group: 73.4% vs 67.7% for RB vs no RB, respectively (p = 0.02). For other surgical types, comprehension higher in the RB group, but not statistically significant |

Adding RB to the iMedConsent program significantly improved pt comprehension; this improvement was greatest in pts undergoing CEA and for overall understanding and understanding the key risks of the procedure No significant diff between groups in quality of decision-making, satisfaction with decision, receiving correct quantity of information, and anxiety about surgical procedure |

| Baker, 2014 [24] | United States |

|

Pts of Erie Family Health Center, age 51–75y; preferred language English or Spanish; previously completed an FOBT, and negative FOBT result from March 1, 2011 to Feb 28, 2012 n = 450 | Adherence to FOBT | Intervention group was much more likely to complete FOBT vs usual care group (82.2% vs 37.3%; p < 0.001) | Intervention improved adherence to FOBT screenings; personal phone calls were not required for most screenings |

| Chalela, 2018 [21] | United States | Choices is a bilingual intervention with 3 components: (1) educational interactive video, (2) low-literacy booklet, and (3) care coordination by pt navigation | English- and Spanish-speaking Latina pts with BC, age ≥ 18y, no initial MD consultation to discuss treatment options, no current or prior clin trial participation Able to understand information in consent form, respond to the computer-based surveys, and interact with educational video n = 73 | Pt understanding of clin trials, consideration of clin trials as a treatment option, and decision-making by surveys | Choices vs controls more effectively improved perceived understanding of clin trials (p = 0.033) and increased consideration of clin trials as treatment option (p = 0.008) Between baseline and post-intervention, intervention group showed significant changes in agreement with stages of decision-readiness statements (p < 0.002); whereas the control group did not (p > 0.05) |

Compared with controls, women who received the Choices intervention were more likely to make positive progress in stages of decision-readiness regarding clin trial participation |

| Jibaja-Weiss, 2011 [25] | United States | Entertainment-based decision aid for BC treatment | Females who visited 1 of 2 breast pathology clinics; diagnosed with early-stage BC, speak English or Spanish, eligible for breast-conserving surgery, did not have additional serious medical conditions n = 100 | BC knowledge, satisfaction with decision-making and decision conflict by Satisfaction with Decision Scale, Satisfaction with Decision-Making Process, 10-item low-literacy version of the Decisional Conflict Scale | At pre-decision point, no significant diff in knowledge between the CPtDA and control groups At pre-surgery assessment, CPtDA patients showed significant improvement in knowledge vs controls (p < 0.001) At 1-y follow-up, control pts knowledge increased nearly to level of the CPtDA group Both groups showed reduced decisional conflict (P < 0.001 for all DCS scales) |

Entertainment education can be an effective strategy for informing women with lower health literacy about options for BC surgery |

| Kuppermann, 2014 [20] | United States | Computerized, interactive decision-support guide alongside no out-of-pocket expense access to prenatal testing | Pregnant women, English- or Spanish-speaking, had not yet undergone screening or diagnostic testing, and were still pregnant at 11 wks gestation n = 710 | Knowledge about testing, risk comprehension, and decisional conflict and decision regret (secondary outcomes) by a 15-item measure based on the Maternal Serum Screening Knowledge Questionnaire, Decisional Conflict Scale, and 5-item Decision Regret Scale | Intervention group had higher knowledge scores vs controls (9.4 vs 8.6) on 15-point scale: mean group diff: 0.82 (95% CI 0.34–1.31; P < 0.001) No sig difference was observed for decisional conflict or decision regret |

Approach could lead to more informed and preference-based decision-making regarding prenatal testing, and fewer women may undergo testing |

| Piette, 2016 [17] | Bolivia | Caregiver feedback: Automated telephone feedback to informal caregivers (CarePartners) while patients received mobile health (m-health) support. | Patients with diabetes and hypertension identified through ambulatory clinics were enrolled with a CarePartner. n = 72 | Pt engagement in m-health support (such as call completion rate) All calls were recorded. During each m-health calls, pts were asked to report their perceived health using a standard general health item. |

M-Health+CP pts were more likely to complete calls and report excellent health compared with those who did not receive CP feedback | Giving feedback to an informal caregiver substantially improved pt engagement in m-health self-care support intervention |

| Poureslami, 2012 [19] | Canada | Pt education on asthma, including self-management, triggers and symptoms, using videos and pamphlets. Group 1 viewed a physician-led knowledge video, Group 2 viewed pt-generated community video, Group 3 viewed both, and Group 4 (comparison group) read pictorial pamphlet only | Physician-diagnosed, adult (≥ 21y) patients with asthma; used asthma medications daily; immigrated to Canada within the past 20y; resided in the Greater Vancouver area during study period; and spoke Mandarin, Cantonese, or Punjabi n = 92 | Pt education (asthma) and self-management measured by questionnaires developed by community researchers | Significant improvements from pre-test to follow-up were observed for all four study groups in terms of proper inhaler use, knowledge of asthma symptoms, and pts’ intention to manage their asthma | Short, simple, culturally, and linguistically appropriate videos and pamphlets can promote patient knowledge of asthma proper inhaler use, and intentions to change behavior. |

| Roter, 2015 [18] | United States | Healthy Babies Healthy Moms [HBHM]) program; 20-min communication skills-based computer program designed to empower women to engage in medical communication more actively during prenatal visits Baby Basics (BB) prenatal guide; face-to-face educational session with study researcher |

Women treated by participating clinician, spoke English, and planned to deliver baby at study hospital n = 83 | Characterization of medical dialog between patient and clinician using the Roter Interaction Analysis System | HBHM vs BB visits featured more pt-centered communication and lower levels of clinician verbal dominance. Diff in both measures were significant for women with adequate literacy (p < 0.05) and suggestive for women with literacy deficits (p < 0.1) |

The HBHM intervention vs BB enhanced medical visit communication for women regardless of literacy deficits. In addition to a more pt-centered communication pattern, women were more verbally active and demonstrated increased use of targeted communication skills. |

| Smith, 2010 [16] | Australia | Pt decision-aids comprised a paper-based interactive booklet and DVD, presenting quantitative risk information on potential outcomes of screening using FOBT vs no testing | Age 55–64y with low educational attainment, spoke mainly English at home, and eligible for bowel cancer screening n = 572 | Informed choice (i.e., adequate knowledge and consistency between attitudes and screening behavior), decision-making skills among low literacy by telephone follow-up interview 2 wks post-package delivery to pt | Pt in the decision-aid group had higher levels of knowledge vs controls (mean [95% CI] score [max 12] 6.50 [6.15–6.84] vs 4.10 [3.85 to 4.36; p < 0.001], decision-aid vs control group). The decision-aid also increased the proportion of participants who made an informed choice (34% vs 12% in the control group, p < 0.001), but resulted in a reduction in participation rate (59% vs 75% in the control group, p = 0.001) | A tailored decision-aid can help support adults to make informed choices about screening for bowel cancer but may result in lower uptake. |

| Tait, 2009 [15] | United States | Standard institutional verbal and written information vs interactive computerized information describing details of diagnostic cardiac catheterization | Age > 18y, at medical center, ~1 h before scheduled elective diagnostic cardiac catheterization n = 135 | Comprehension was measured using semistructured interviews | Pts receiving ICI intervention vs SI had significantly greater improvement in understanding (net change, 0.81 [95% CI 0.01–1.6]) Significantly more pts in ICI vs SI group had complete understanding of the risks associated with cardiac catheterization (53.6% vs 23.1%, p = 0.001) |

ICI program may be more effective than conventional written consent information for improving patient understanding of cardiac catheterization |

| Intervention Subtype: in-person sessions | ||||||

| Carroll, 2019 [35] | United States | Six 90-min group training sessions on using an ePersonal Health Record on a handheld mobile device, and a single 20–30 min individual coaching session | Confirmed HIV diagnosis, age ≥ 18y, some proficiency in English, and receipt of HIV/primary care at a participating clinic site n = 359 | Pt activation by PAM Secondary outcomes: changes in eHEALS, DSES, PICS, health SF-12, receipt of HIV-related care, and change in HIV viral load | Intervention significant diff vs control group in PAM (diff 2.82: 95% CI 0.32–5.32) Effect was largest among pts with lowest quartile PAM at baseline (p < 0.05). Intervention doubled the odds of improving 1 level on PAM (OR 1.96 [95% CI 1.16–3.31]). Intervention effects were similar by race/ethnicity and education, except eHealth literacy, where effects were stronger for pts from a diverse racial or ethnic background or with a lower level of education |

A multimodal pt self-management group eHealth invention modestly improved pt activation and empowerment |

| Han, 2017a [34] | United States | Individualized brochure, health literacy skills training, telephone counseling vs an education al control group | Korean American women, age 21–65y, no mammogram (ages≥40y only) or Pap test within the past 24 mo, able to read and write Korean or English n = 560 | Cancer screening behaviors; and cancer knowledge using the following questionnaires: the Assessment of Health Literacy in Cancer Screening, Breast Cancer Knowledge Test and Cervical Cancer Knowledge test. A decisional balance measure was used to assess perceptions about cancer screening | The odds of getting a mammogram were 18.5× higher (95% CI 9.2, 37.4) in the intervention group vs the control group when adjusting for covariates. Odds of getting a mammogram in women who read all the intervention materials were 31.1× higher (95% CI 15.1–63.9) vs control group when adjusting for covariates | A health-literacy focused intervention significantly improved mammogram and Pap test rates vs the control group |

| Solhi, 2019 [33] | Iran | Intervention group had 4 educational sessions with group counseling including topics on health literacy and self-care during pregnancy and its impact on self-care in pregnant women | Healthy pregnant women with no chronic diseases at 12–28-wk gestational age, who were pts at 1 of 2 health service centers in Pakdasht n = 80 | Impact of health literacy education on self-care among pregnant women by 2 dedicated questionnaires focusing on pregnancy period: self-care (21 questions), and health literacy (24 questions) | 1 mo after intervention: Significant diff (p < 0.001) in mean scores of the total self-care (65 ± 6.23 vs 76.77 ± 4.28) and total health literacy (30.95 ± 4.62 vs 40 ± 3.54) for control vs intervention group 2 mo after intervention: Significant diff (p < 0.001) in mean scores of the total self-care (66 ± 6.72 vs 78 ± 3.98) and total health literacy (31.55 ± 4.56 vs 40.57 ± 3.09) for control vs intervention group | Educational groups increased involvement in self-care during pregnancy and promoted health literacy |

| Street Jr., 2010 [32] | United States | Tailored education-coaching (TEC) intervention to help pts learn pain management and communication skills | English-speaking, age 18–80y, locally advanced or disseminated lung, breast, prostate, head and neck, esophageal, colorectal, kidney, bladder cancer or melanoma skin cancer, scheduled to see participating physician, recent worst pain (past 2 wks) score ≥ 4 (0–10 scale) or pain in past 2 wks that at least moderately interfered with normal daily activities n = 148 | Pt total active participation, and pain-specific active participation during physician consultations measured with a validated coding system | In bivariate analysis, pts in the TEC intervention displayed more pain-specific active participation than pts in the EUC control group (mean = 6.21 vs 4.63 utterances), p = 0.008 In multivariate analysis, there was no difference in total active participation between TEC and EUC The TEC intervention led to pts asking more questions, being more assertive, and expressing more pain related concerns vs EUC (p = 0.009) |

Pts’ overall participation did not differ between the 2 groups; pts in the TEC intervention group showed increased pain-specific active participation and asked more questions, were more assertive, and expressed more pain-related concerns vs EUC |

| Blancafort Alias, 2021c [36] | Spain | Community program consisted of 12 group sessions of 15 people, held every week for 2 h 9 of 12 sessions took place in primary care center, 3 conducted in local public settings, eg, physical activity, supermarket, social activities of interest to group members Sessions were led by 9 health and social care professionals | Participants recruited from attendees of 16 primary care centers in low-income neighborhoods Individuals were community-dwelling, age ≥ 60y, and viewed their health as fair or poor n = 358 | Self-perceived health by SF-12 questionnaire and EQ-5D Self- management by Appraisal of Self Care Agency Scale Health literacy by HLS-EU-16 Use of health resources by visits to a nurse, GP, social worker, emergency units, and hospitalizations |

Intervention group showed higher levels of understanding medical information from baseline (−0.62 [95% CI−1.10, −0.13]), p < 0.05; whereas the control group did not (−0.45 [95% CI− 0.99, 0.08], p ≥ 0.05 No significant differences were found between study groups for self-perceived health or self- management 9 mo post-intervention, the intervention group showed increased visits to a nurse compared with baseline (1.72 [95% CI 0.43, 3.02], p < 0.01); whereas the control group did not (−0.19 [95% CI−1.64, 1.26], p ≥ 0.05) |

The intervention may improve health literacy regarding increased understanding of medical information Promoting health among older adults in urban, disadvantaged areas, and emphasizing self-management, health literacy, and social capital can help address inequity |

All studies listed are RCTs.

Avg, average; BC, breast cancer; CI, confidence interval; Clin, clinical; CPtDA, computerized patient decision aid; CRC, colorectal cancer; Diff, difference; DSES, Decision self-efficacy; eHEALS, eHealth Literacy; EUC, educationally-enhanced usual care; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; GP, general practitioner; HLS-EU-16, Health Literacy Scale -EU-16; ICI, interactive computerized information; ICF, informed consent form; M-health+CP, mobile health+CarePartner; MICCA, Modular Informed Consent Comprehension Assessment; OR, odds ratio; PACE, Provision of information, Asking questions, Checking on understanding, Expressing concerns; PAM, Patient Activation Measures; PICS, Perceived Involvement in Care Scale; PK, pharmacokinetics; pt, patient; QoL, quality of life; QuIC, Quality of Informed Consent; RB, Repeat Back; RCT, randomized clinical trial; SH-12, Short Form 12; SD, standard deviation; SI, standard information; SIDCER, Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review; SURE, sure of myself, understand information, risk-benefit ratio, encouragement; TEC, Tailored Education Coaching.

Cluster RCT.

Open label RCT.

Individually randomized clinical trial.

The most common type of health literacy intervention was multimedia or technology-based (11 studies). For studies in the multimedia category, six tested a single intervention, three used a single intervention with multiple components, and two compared multiple interventions. Five studies used a computerized interactive tool, three used videos/DVDs, two used an automated phone-based tool and one used an entertainment-based decision aid. Studies assessed outcome measures through interviews [15–17], questionnaires developed or adapted specifically for the study [18–23], number of patients completing screening tests [24], and through externally developed outcome measures such as Satisfaction with Decision Scale (SWD) [25]. Computerized interactive tools, videos/DVDs, and the entertainment-based decision aid significantly improved patients’ knowledge, understanding and comprehension of consent, study assessments, and clinical procedures [15,16,19–23,25], the mail- and telephone-based reminders improved patient adherence to preventive screening [24], the phone calls improved patient engagement [17], and the computer program versus education session reduced the level of clinician verbal dominance during clinician visits [18].

Six studies used simplification of written material; three of these used a simplified informed consent form, one used a decision aid, one used an information booklet, and one used rapid ethical assessment, with the focus on one intervention in all but one study [26]. Although four of these six studies measured patient comprehension or understanding, all used unique outcome measures. Simplified or shortened informed consent forms improved patient comprehension and understanding [26–28], the rapid ethical assessment improved comprehension and quality of informed consent [29], the decision aid increased the rate of informed choice [30], and the information booklets improved reading ease [26] and parent participation in medical consultations [31].

Of the five studies using in-person sessions, two used group sessions, two used one-on-one coaching or counseling, and one study combined group training with individual coaching. Outcome measures included a validated coding system [32], questionnaires [33], a knowledge test [34], and externally developed outcome measures, such as Patient Activation Measures (PAM) [35], and Health Literacy Scale (HLS-EU-16) [36]. Group sessions led to improved health literacy and understanding [33,36], the individual sessions led to increased rates of preventive testing [34] and increased reporting of pain [32]. The combined group and individual sessions led to improved patient activation and empowerment [35].

Although there was no principal statistical measure, most studies (n = 12) used mean differences in outcome scores to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions. For the 12 studies excluded due to having no significant change in health literacy outcome (p ≥ 0.05, or other measure of significance as defined in the study), a review of their abstracts did not identify any studies reporting on the same intervention as one of the included studies. No studies reporting a significant reduction in the relevant outcomes were identified in this review.

4. Discussion

Based on 22 studies, this systematic review identified and qualitatively evaluated 27 unique health literacy interventions that led to significant improvements in health literacy. These interventions included multimedia or technology-based approaches, simplification of written material, and facilitation of in-person sessions. These interventions were reported to lead to significant improvements in outcomes including health literacy, comprehension, decision-making, and patient activation. This information on practices that were successful in improving health literacy could assist organizations such as NASEM to develop evidence-based best practice guidelines for incorporating health literacy into clinical trials.

The large number of unique interventions identified in this study and the timing of these interventions throughout different stages of medical care and the clinical trial process suggest that there is broad scope for incorporating health literacy into clinical trials. Significant improvements in health literacy were seen during preventive screening, decision-making, informed consent, self-management, and symptom reporting. Similarly, a variety of successful approaches at different stages of the clinical trial process were shared during the NASEM workshop on Health Literacy in Clinical Research [5]. These findings show that health literacy interventions have value throughout the healthcare journey, and could impact clinical trial designs by supporting the incorporation of these interventions at all stages of the trial process. The value of health literacy interventions in the clinical trial process was further demonstrated by a study where a modified consent process enabled 98% participants to achieve complete understanding of consent information, irrespective of literacy and language barriers [37]. In the present review, successful strategies for improving health literacy included using plain language, shortening content, using bullet points, and including diagrams. This is consistent with published guidelines on simplifying participant information leaflets and informed consent forms [38]. The present review also identified a study showing the benefits of tailored support and integration of the community’s language and cultural beliefs for improving self-management and informative choice making [19]. This is important, since speaking a language other than English before starting school is a risk factor for low health literacy [3], and many of the other studies required participants to be able to speak and/or read English. Overall, this review demonstrates that health literacy interventions have value, and best practice guidelines should therefore promote health literacy principles not just during informed consent, but throughout the whole clinical trial journey.

The most common type of intervention was inclusion of multimedia or technology-based approaches, which may reflect the importance of diversity in the way information is presented. Informed consent forms and patient information is traditionally provided in written form, and even in recent trials, is often of high complexity [39]. However, in this study, most successful health literacy interventions were either multimedia/technology-based or face-to-face. This may reflect the different preferences people have for the way they receive and process information, as health literacy has been reported to improve when health education is delivered according to the preferred learning styles of individuals [40]. In addition to improving health literacy for the individuals involved, presenting information in multiple forms can also benefit the clinical trial process, because it promotes diversity of trial participants, which is paramount to ensuring the representativeness of the trial population and thus the generalizability of trial results. The benefit of presenting information in multiple forms should, however, be balanced against the practicalities of different approaches. Over-reliance on mobile apps and online resources could exacerbate healthcare disparities, since people who are older, have a lower level of education or are from a diverse racial or ethnic background are at the highest risk of experiencing low digital literacy and/or barriers to technology access [41,42]. On the other hand, individual coaching sessions may be cost-prohibitive for large research trials. Therefore, in addition to the effectiveness of the intervention, researchers should also consider participant access and resource availability when choosing and incorporating health literacy practices into clinical trial design. Overall, this review highlights the importance of considering the multiple ways people take in information, and recommends that best practice guidelines broaden recommendations beyond written materials.

All 22 studies used different outcome measures to assess improvements in health literacy, suggesting a need for standardization in how health literacy is measured and reported. Standardization is important because, without a principal statistical measure, it is not possible to quantitatively evaluate the relative effectiveness of different interventions. A similar limitation was noted in another systematic review of interventions to improve comprehension in the informed consent process [43], and parallels issues with standardization of assessment tools in digital literacy [44]. Such quantitative evaluation would improve the robustness of the data feeding into any guideline recommendations. A key challenge with standardizing outcomes would be the multiple components of health literacy. Beyond measuring comprehension, robust measures of health literacy would need to incorporate the ability to use health information to inform decisions and actions. Patient engagement and actions may be more difficult to measure in a standardized way than outcomes such as comprehension and measures used need to be appropriate for the relevant trial population. To balance the need for standardization between studies with the need for tools that are appropriate for the population and outcome being tested, an alternative approach could be to use standardized reporting tools that are modified or adapted to suit the target population. An example of this would be the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy [FACT], which has various versions for patients with different types of cancer. In this way, best practice guidelines could potentially recommend a hybrid approach to standardizing outcome measures for health literacy – whereby studies use validated instruments to measure health literacy, but are able to adapt these for the target populations as appropriate.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, this is a qualitative synthesis, and the categorizations should therefore be interpreted with caution. Also, with 22 included articles, our study included a smaller number of articles compared with other systematic reviews in this field and most studies evaluated interventions at various stages of healthcare and not at stages of a clinical trial. To promote appropriate data capture, we implemented controls such as having the search terms reviewed and agreed by members of the NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy [5], and having two reviewers independently compile results, with a third reviewer to resolve discrepancies. However, despite these controls, similar systematic reviews included more studies. For example, 52 studies were included in a review of interventions to improve comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures [43]; and 52 studies were included in a review of US-based studies on health disparities and outcomes in otology [45]. There are a number of potential reasons for this difference. Firstly, the search terms and inclusion criteria were more narrowly defined in our study. For example, our review included only randomized clinical studies, whereas the studies above included other trial designs. Secondly, gray literature, such as conference proceedings, posters, and pharmaceutical company reports, were excluded from this analysis. Gray literature should be included in a follow-up study and would help ensure that all relevant information is captured, and the most up-to-date data are included. Thirdly, papers that did not report a statistically significant improvement in health literacy outcomes were excluded. Including data on interventions that were not effective could reduce the risk of reporting bias, assist in determining the generalizability of results, and contribute important learnings for future trial designs. Another reason could be that most reviews don’t rely solely on database searches, but also add articles as the study unfolds by methods such as citation tracking and researching references of references [46].

Overall, although our study may not be an exhaustive review of the literature, our research does capture key trends in health literacy interventions, and confirms and extends the findings of other systematic reviews, including identifying a lack of standardization of health literacy outcome measures [43]. This study forms a valuable contribution to the field by demonstrating that health literacy interventions have value at various stages of healthcare and the clinical trial process, identifying techniques researchers and organizations can use to improve clinical trial designs, and making recommendations for how these data can support best practice guidelines. Although inclusion of additional studies focused on similar interventions would unlikely alter the key outcomes of this review, further research using broader search terms, incorporating gray literature, and including studies with negative or nonsignificant results could improve the robustness of this information, and further support the development of best practice guidelines.

5. Conclusions

Based on 22 included studies, this systematic review identified and qualitatively evaluated 27 unique health literacy interventions that led to significant improvements in health literacy. Multimedia or technology-based approaches, simplification of written material, and facilitation of in-person sessions led to significant improvements in outcomes such as health literacy, comprehension, decision-making, and patient activation. Findings suggest the need for improved standardization of health literacy measures and tailoring of interventions to meet the needs of patients with varying degrees of health literacy. The above studies demonstrate that health literacy practices can be successfully incorporated into various stages of healthcare and the clinical trial process. Along with a follow-up systematic review of gray literature, this information on practices that were successful in improving health literacy could assist organizations such as NASEM to develop evidence-based best practice guidelines for incorporating health literacy into clinical trials. This could ultimately lead to a more patient-centered clinical trial process and improved outcomes for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy, who reviewed the search terms used in this review. Medical writing support was provided by Susan Tan, PhD, and Diane Hoffman, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and funded by Pfizer. Pfizer authors note that the opinions/views expressed are their own and may not reflect those of Pfizer. The Merck author notes that the opinions/views expressed are their own and may not reflect those of Merck.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer. Medical writing support was funded by Pfizer.

Abbreviations12:

- BC*

breast cancer

- CI*

confidence interval

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- Clin*

clinical

- CPtDA*

computerized patient decision aid

- CRC*

colorectal cancer

- Diff*

difference

- DSES*

decision self-efficacy

- eHEALs

eHealth Literacy

- EUC*

educationally-enhanced usual care

- FACT

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy

- FOBT*

fecal occult blood testing

- HLS-EU-16

Health Literacy Scale EU-16

- ICI*

interactive computerized information

- ICF*

informed consent form

- mHealth+CP*

mobile health+CarePartner

- MICCA

Modular Informed Consent Comprehension Assessment

- NASEM

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine

- PACE

Provision of information, Asking questions, Checking on understanding, Expressing concerns

- PAM

Patient Activation Measures

- PICS*

Perceived Involvement in Care Scale

- PK*

pharmacokinetics

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- Pt*

patient

- QoL*

quality of life

- QuIC*

Quality of Informed Consent

- RB*

Repeat Back

- RCT*

randomized clinical trial

- REALM

Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy

- RoB2

Cochrane Risk of Bias Comparison tool

- SD*

standard deviation

- SF-12*

Short Form-12

- SI*

standard information

- SIDCER*

Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review

- SWD

Satisfaction with Decision Scale

- TEC*

Tailored Education Coaching

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Mehnaz Bader: Employee of Pfizer.

Linda Zheng: No conflicts of interest to declare.

Deepika Rao: No conflicts of interest to declare.

Olayinka Shiyanbola: No conflicts of interest to declare.

Laurie Myers: Employee and stockholder of Merck & Co., Inc.

Terry Davis: No conflicts of interest to declare.

Catina O’Leary: Employee of Health Literacy Media.

Michael McKee: No conflicts of interest to declare.

Michael Wolf: Consultancy from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, LUTO UK, Sanofi, and Lundbeck; and grants/contract support from Pfizer, Eli Lilly, and Amgen.

Annlouise R. Assaf: Employee of and owns stock in Pfizer.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mehnaz Bader: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Linda Zheng: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Deepika Rao: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Olayinka Shiyanbola: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Laurie Myers: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Terry Davis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Catina O’Leary: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Michael McKee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Michael Wolf: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Annlouise R. Assaf: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2022.106733.

References

- [1].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. (last update August 24, 2021). https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/healthy-people/healthy-people-2030/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030. Accessed November, 2021.

- [2].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. Health Literacy. https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/health-literacy, 2021. Accessed December, 2021.

- [3].Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C, The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy: U.S Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Washington, DC, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rikard RV, Thompson MS, McKinney J, Beauchamp A, Examining health literacy disparities in the United States: a third look at the National Assessment of adult literacy (NAAL), BMC Public Health 16 (2016) 975, 10.1186/s12889-016-3621-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, Health Literacy in Clinical Research: Practice and Impact: Proceedings of a Workshop, 2020, 10.17226/25616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].National Library of Medicine, An Introduction to Health Literacy (last update October 9th, 2021), https://nnlm.gov/guides/intro-health-literacy. Accessed November, 2021.

- [7].Clark LT, Watkins L, Pina IL, Elmer M, Akinboboye O, Gorham M, et al. , Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers, Curr. Probl. Cardiol 44 (2019) 148–172, 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, Roundtable on Health Literacy. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/roundtable-on-health-literacy, 2021. Accessed December, 2021.

- [9].McCaffery KJ, Holmes-Rovner M, Smith SK, Rovner D, Nutbeam D, Clayman ML, et al. , Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids, BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak 13 (Suppl. 2) (2013) S10, 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Garcia SF, Hahn EA, Jacobs EA, Addressing low literacy and health literacy in clinical oncology practice, J. Support. Oncol 8 (2010) 64–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. , The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews, BMJ. 372 (2021), n71, 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Veritas Health Innovation, Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2021.

- [13].Queens University Library. Systematic Reviews & Other Syntheses. (last update October 29, 2021). https://guides.library.queensu.ca/knowledge-syntheses/covidence.

- [14].Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. , The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials, BMJ. 343 (2011), d5928, 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Moscucci M, Brennan-Martinez CM, Levine R, Patient comprehension of an interactive, computer-based information program for cardiac catheterization: a comparison with standard information, Arch. Intern. Med 169 (2009) 1907–1914, 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ, A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial, BMJ. 341 (2010), c5370, 10.1136/bmj.c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Piette JD, Marinec N, Janda K, Morgan E, Schantz K, Yujra AC, et al. , Structured caregiver feedback enhances engagement and impact of mobile health support: a randomized trial in a lower-middle-income country, Telemed. J. E Health 22 (2016) 261–268, 10.1089/tmj.2015.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Roter DL, Erby LH, Rimal RN, Smith KC, Larson S, Bennett IM, et al. , Empowering Women’s prenatal communication: does literacy matter? J. Health Commun 20 (Suppl. 2) (2015) 60–68, 10.1080/10810730.2015.1080330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Poureslami I, Nimmon L, Doyle-Waters M, Rootman I, Schulzer M, Kuramoto L, et al. , Effectiveness of educational interventions on asthma self-management in Punjabi and Chinese asthma patients: a randomized controlled trial, J. Asthma 49 (2012) 542–551, 10.3109/02770903.2012.682125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kuppermann M, Pena S, Bishop JT, Nakagawa S, Gregorich SE, Sit A, et al. , Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing: a randomized clinical trial, JAMA. 312 (2014) 1210–1217, 10.1001/jama.2014.11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chalela P, Munoz E, Gallion KJ, Kaklamani V, Ramirez AG, Empowering Latina breast cancer patients to make informed decisions about clinical trials: a pilot study, Transl. Behav. Med 8 (2018) 439–449, 10.1093/tbm/ibx083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Afolabi MO, McGrath N, D’Alessandro U, Kampmann B, Imoukhuede EB, Ravinetto RM, et al. , A multimedia consent tool for research participants in the Gambia: a randomized controlled trial, Bull. World Health Organ. 93 (2015), 10.2471/BLT.14.146159, 320–8A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fink AS, Prochazka AV, Henderson WG, Bartenfeld D, Nyirenda C, Webb A, et al. , Enhancement of surgical informed consent by addition of repeat back: a multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial, Ann. Surg 252 (2010) 27–36, 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e3ec61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, Weil J, Balsley K, Ranalli L, et al. , Comparative effectiveness of a multifaceted intervention to improve adherence to annual colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: a randomized clinical trial, JAMA Intern. Med 174 (2014) 1235–1241, 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Granchi TS, Neff NE, Robinson EK, Spann SJ, et al. , Entertainment education for breast cancer surgery decisions: a randomized trial among patients with low health literacy, Patient Educ. Couns 84 (2011) 41–48, 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Benatar JR, Mortimer J, Stretton M, Stewart RA, A booklet on participants’ rights to improve consent for clinical research: a randomized trial, PLoS One 7 (2012), e47023, 10.1371/journal.pone.0047023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kim EJ, Kim SH, Simplification improves understanding of informed consent information in clinical trials regardless of health literacy level, Clin. Trials 12 (2015) 232–236, 10.1177/1740774515571139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Koonrungsesomboon N, Teekachunhatean S, Hanprasertpong N, Laothavorn J, Na-Bangchang K, Karbwang J, Improved participants’ understanding in a healthy volunteer study using the SIDCER informed consent form: a randomized-controlled study, Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol 72 (2016) 413–421, 10.1007/s00228-015-2000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Addissie A, Abay S, Feleke Y, Newport M, Farsides B, Davey G, Cluster randomized trial assessing the effects of rapid ethical assessment on informed consent comprehension in a low-resource setting, BMC Med. Ethics. 17 (2016) 40, 10.1186/s12910-016-0127-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Reder M, Kolip P, Does a decision aid improve informed choice in mammography screening? Results from a randomised controlled trial, PLoS One 12 (2017), e0189148, 10.1371/journal.pone.0189148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cegala DJ, Chisolm DJ, Nwomeh BC, A communication skills intervention for parents of pediatric surgery patients, Patient Educ. Couns 93 (2013) 34–39, 10.1016/j.pec.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Street RL Jr., Slee C, Kalauokalani DK, Dean DE, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL, Improving physician-patient communication about cancer pain with a tailored education-coaching intervention, Patient Educ. Couns 80 (2010) 42–47, 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Solhi M, Abbasi K, Ebadi Fard Azar F, Hosseini A, Effect of health literacy education on self-Care in Pregnant Women: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J community based Nurs, Midwifery. 7 (2019) 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Han HR, Song Y, Kim M, Hedlin HK, Kim K, Ben Lee H, et al. , Breast and cervical cancer screening literacy among Korean American women: a community health worker-led intervention, Am. J. Public Health 107 (2017) 159–165, 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Carroll JK, Tobin JN, Luque A, Farah S, Sanders M, Cassells A, et al. , “get ready and empowered about treatment” (GREAT) study: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial of activation in persons living with HIV, J. Gen. Intern. Med 34 (2019) 1782–1789, 10.1007/s11606-019-05102-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Blancafort Alias S, Monteserin Nadal R, Moral I, Roque Figols M, Rojano ILX, Coll-Planas L, Promoting social capital, self-management and health literacy in older adults through a group-based intervention delivered in low-income urban areas: results of the randomized trial AEQUALIS, BMC Public Health 21 (2021) 84, 10.1186/s12889-020-10094-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sudore RL, Landefeld C, Williams B, Barnes D, Lindquist K, Schillinger D, Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study, J. Gen. Intern. Med 21 (2006) 1009, 10.1007/BF02743161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Coleman E, O’Sullivan L, Crowley R, Hanbidge M, Driver S, Kroll T, et al. , Preparing accessible and understandable clinical research participant information leaflets and consent forms: a set of guidelines from an expert consensus conference, Res. Involv. Engagem 7 (2021) 31, 10.1186/s40900-021-00265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Emanuel EJ, Boyle CW, Assessment of length and readability of informed consent documents for COVID-19 vaccine trials, JAMA Netw. Open 4 (2021), e2110843, 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Grebner L, Addressing learning style needs to improve effectiveness of adult health literacy education, Int. J. Health Sci. (IJHS) 3 (2015) 93–106, 10.15640/ijhs.v3n1a6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mamedova S, Pawlowski E, Hudson L, U.S. Department of Education Stats in Brief: A Description of U.S. Adults Who Are Not Digitally Literate. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2018/2018161.pdf, 2018.

- [42].Mitchell UA, Chebli PG, Ruggiero L, Muramatsu N, The digital divide in health-related technology use: the significance of race/ethnicity, Gerontologist. 59 (2019) 6–14, 10.1093/geront/gny138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Glaser J, Nouri S, Fernandez A, Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Klein-Fedyshin M, et al. , Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures: an updated systematic review, Med. Decis. Mak 40 (2020) 119–143, 10.1177/0272989X19896348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Laanpere M, UNESCO Institute for Statistics: Recommendations on Assessment Tools for Monitoring Digital Literacy within UNESCO’s Digital Literacy Global Framework. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ip56-recommendations-assessment-tools-digital-literacy-2019-en.pdf, 2019.

- [45].Lovett B, Welschmeyer A, Johns JD, Mowry S, Hoa M, Health disparities in otology: a PRISMA-based systematic review, Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 1945998211039490 (2021), 10.1177/01945998211039490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Greenhalgh T, Peacock R, Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources, BMJ. 331 (2005) 1064–1065, 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.