Abstract

This report details ongoing efforts to improve integration in the 2 years following implementation of the Primary Care Behavioral Health model at a general internal medicine clinic of an urban academic medical center. Efforts were informed by a modified version of the validated Level of Integration Measure, sent to all faculty and staff annually. At baseline, results indicated that the domains of systems integration, training, and integrated clinical practices had the greatest need for improvement. Over the 2 years, the authors increased availability of behavioral medicine appointments, improved depression screening processes, offered behavioral health training for providers, disseminated clinical decision support tools, and provided updates about integration progress during clinic meetings. Follow-up survey results demonstrated that physicians and staff perceived improvements in integration overall and in targeted domains. However, the main ongoing barrier to integration was insufficient behavioral health staff to meet patient demand for behavioral health services.

Keywords: primary care, behavioral health, integration, quality improvement, follow-up study

Primary care settings are the ad hoc site for behavioral health (BH) care in the United States1 because of the long-standing shortage of BH providers,2 low insurance reimbursement for BH care,3 and stigma associated with BH.4 As a result, the Institute of Medicine and the World Health Organization have called for increased BH integration into primary care.5 Evidence has demonstrated that BH integration may lower health care costs,6 improve depression symptoms,7 improve adherence,8 and decrease physician stress.9 Although its many benefits to patients, providers, and the health care system are accepted, few studies have described the complex process of integration.

One of the main approaches to integration is the Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model, in which primary care physicians (PCPs) and behavioral health providers (BHPs) working in the same clinical space use a team-based approach to manage biopsy-chosocial factors affecting patients’ health.10 Implementation of PCBH can be challenging because the cultures of primary care and traditional BH care are different, and not many BHPs are trained to work in the primary care setting.11 Additionally, integration requires changes at multiple levels: staffing, clinical workflow, information technology, leadership, and patient engagement.12

In 2015, University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) began implementing PCBH in its internal medicine clinic. The quality improvement (QI) efforts during the first 6 months of implementation were described previously.13 The present paper presents the continued efforts to integrate BH during the subsequent 2 years (2016–2018) and discusses how problems that arose during this process were identified and solved.

Methods

Setting

Details about the initial 6 months of integration were published previously.13 Briefly, an interdisciplinary team was formed in December 2014 to implement integrated care at the UCM general internal medicine clinic, called the Primary Care Group (PCG). PCG serves ~26,000 patients (57% private insurance, 32% Medicare, 12% Medicaid) and employs 150 PCPs (40 faculty, 110 residents, about 18 full-time equivalents [FTEs]). Since its inception, the Primary Care Group-Behavioral Health Integration Program (PCG-BHIP) team has met at least monthly and led efforts to integrate care. The PCG Behavioral Medicine (BMED) service was established in April 2015 with 1 health psychologist (NB) available 1 half-day per week for consultations, warm handoffs (ie, PCPs directly introducing patients needing BH services to a BMED psychologist during clinic visits), joint visits, and scheduled appointments. In September 2015, the BMED service expanded to 3 to 4 half-day clinics per week. The BMED service is an advanced training site in integrated primary care and clinical health psychology for clinical psychology externs, interns, and postdoctoral fellows. In 2015–2016, the BMED service trained 1 intern and 1 extern; in 2016–2018, the BMED service trained 1 intern, 1 extern, and 1 postdoctoral fellow per year. The BMED service expanded to 5 half-day clinics per week in 2018, seeing an average of 87 patients per month for scheduled visits and 16 patients per month via warm handoff. By April 2018, 67% of patients referred for UCM BH services from PCG were referred to BMED (versus another UCM psychiatry or psychology clinic). The ratio of PCP:BH providers improved from 75:1 to 37.5:1 (FTE ratio, 750:1 to 75:1) from April 2015 to June 2018.

Measures

As previously described,13 a modified version of the Level of Integration Measure (LIM)—a validated 32-item instrument that assesses the degree of integration of 6 domains—was used: clinical practice (PCPs and BHPs regularly collaborate on patient care), systems integration (organizational systems and workflows facilitate identification and treatment of BH needs), training (PCPs and BHPs share knowledge by attending training sessions led by one another), interdisciplinary alliance (PCPs and BHPs trust and respect each other), beliefs and commitment (the clinic prioritizes integrated care), and leadership (clinic administrators prioritize integrated care) (see Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1, available at http://links.lww.com/AJMQ/A9, for survey questions).14 Within each domain, average scores were calibrated on a scale of zero (low) to 100 (high). A score of 80 or higher has been achieved by highly integrated clinics.14 Survey items were added asking participants to rate their satisfaction with integration efforts and BH resources, and their degree of confidence in BH appointment scheduling after referral to the service. Finally, a question at the end of the survey allowed responders to write in suggestions. The results of the LIM survey directed ongoing QI efforts. All surveys were created and distributed through research electronic data capture (REDCap),15 a secure online survey and data management system.

Study Population and Design

The baseline survey of faculty PCPs, psychologists, and clinical staff was conducted in Fall 2015, when the BMED service was staffed for the academic year. Follow-up surveys were conducted at 6 months (May 2016; PCP, N = 29; psychologist, N = 3; staff, N = 14),13 18 months (May 2017; PCP, N = 22; psychologist, N = 2; staff, N = 18), and 30 months (May 2018; PCP, N = 29; psychologist, N = 2; staff, N = 11). At each time point, up to 3 email reminders were sent to complete the survey. For those who did not complete the online version, paper surveys were distributed at meetings, in clinic, and via campus mail. The PCG-BHIP was formally determined to be QI and therefore was not overseen by the UCM Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

This paper focuses on the 18- and 30-month survey results. Overall and domain scores were calculated for all respondents and stratified by providers (PCPs and psychologists) versus staff (medical assistants [MAs]), licensed practical nurses, and registered nurses). Bivariate analyses were performed using Fisher exact tests, t tests, and 1-way analysis of variance (with post hoc Tukey’s honestly significant difference test), as appropriate, using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Survey response rates were 73% (N = 41/56; 23/34 PCPs, 1/2 psychologists, 17/20 staff) at 18 months and 73% at 30 months (N = 41/56; 29/40 PCPs, 2/2 psychologists, 10/14 staff).

Table 1 presents the overall score for the LIM survey at 6, 18, and 30 months, as well as the 6 domain scores. The lowest scoring LIM domains were targeted for continuous QI efforts, which at 6 months were systems integration, training, and integrated clinical practices (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Level of Integration Scores at 6, 18, and 30 Months.

| Domain | 6 mo (N = 52), mean (SD) | 18 mo (N = 58), mean (SD) | 30 mo (N = 42), mean (SD) | 6 vs 18 mo; P | 6 vs 30 mo; P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated clinical practices | 68.9 (9.7) | 71.3 (11.3) | 72.0 (11.2) | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| Systems integration | 64.2 (8.8) | 67.6 (9.6) | 68.7 (8.4) | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Training | 65.7 (11.0) | 70.0 (11.8) | 70.0 (13.3) | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Interdisciplinary alliance | 77.2 (13.6) | 82.5 (14.4) | 84.1 (13.7) | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| Beliefs and commitment | 78.8 (11.9) | 83.4 (12.2) | 84.3 (11.7) | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Leadership | 78.0 (14.2) | 76.0 (12.9) | 79.6 (13.4) | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| Overall | 70.5 (8.0) | 73.7 (9.4) | 74.6 (8.6) | 0.07 | 0.02 |

Table 2.

Quality Improvement Efforts to Improve Systems Integration, Training, and Integrated Clinical Practices Between 6 and 18 Months (June 2016 to May 2017).

| Domain | Item (% of providers and staff who agree at 6 mo/18 mo) | Activity (date) |

|---|---|---|

| Systems integration | Clinic treatment plans reflect an integrated approach to patients’ behavioral and physical health needs (39%/58%) | Added new topics (eg, insomnia, grief) to smart phrases in EHR for PCPs to refer to or attach to after-visit summaries for patients (July 2016 to February 2017) |

| Added comprehensive order set in EHR with options to address behavioral health needs (eg, consults to psychiatry, common diagnoses) (September 2016 to October 2016) | ||

| The clinic systematically detects and serves the behavioral health needs of patients (25%/38%) | Distributed antidepressant decision aid to facilitate shared decision-making (June 2016) | |

| Developed and distributed new panic (July 2016) and suicide (May 2017) CDS tools in response to provider requests | ||

| Updated depression CDS tool (April 2017) | ||

| Depression screening health maintenance topic and BPA in EHR (June 2016 to May 2017) | ||

| Depression screening report cards emailed to providers monthly (July 2016 to October 2016, February 2017 to May 2017) | ||

| Pilot tested medical assistants administering PHQ for 3 PCPs (November 2016 to May 2017) | ||

| The PCG has a sufficient number of BMED specialists on site (17%/28%) | Began recruiting for full-time health psychologist position (November 2016) | |

| The clinic systematically tracks the progress of behavioral health treatment (23%/30%) | Email sent to PCP if appointment not scheduled for patient referred to psychiatry (August 2016 to October 2016, March 2017 to May 2017) | |

| BMED is integrated into the workflow of the clinic (27%/69%) | Updated and disseminated BMED promotional and informational materials (August 2016, January 2017, April 2017) | |

| Training | All clinic staff receive integrated care training (25%/26%) | Behavioral health presentation at clinic staff meeting (June 2016) |

| PCPs and BMED specialists provide training for each other and the rest of clinic staff (39%/56%) | PCG-BHIP update at internal medicine section meeting (October 2016) | |

| Behavioral health presentation for internal medicine residents (January 2017) | ||

| Clinical Practice | BMED specialists are readily available to see patients and consult with PCPs in the clinic (46%/37%) | Expanded number of BMED clinics per week (April 2017) |

| PCPs and BMED specialists regularly consult about patient care in the clinic (46%/65%) | PCPs and psychologists colocated (continuous) | |

| PCPs and BMED specialists collaborate in making decisions about mutual patients in the clinic (58%/72%) | Joint visit educational experience for first-year residents with psychologists |

Abbreviations: BHIP, Behavioral Health Integration Program; BMED, behavioral medicine; BPA, best practice alert; CDS, clinical decision support; EHR, electronic health record; PCG, Primary Care Group; PCP, primary care physician; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Quality Improvement Efforts to Improve Systems Integration, Training, and Integrated Clinical Practices Between 18 and 30 Months (June 2017 to May 2018).

| Domain | Item (% of providers and staff who agree at 18 mo/30 mo) | Activity (date) |

|---|---|---|

| Systems integration | Clinic treatment plans reflect an integrated approach to patients’ behavioral and physical health needs (58%/90%) | Added new topics (eg, relaxation, negative thoughts) to smart phrases in EHR for PCPs to refer to or attach to after-visit summaries for patients (November 2017) |

| The clinic systematically detects and serves the behavioral health needs of patients (37%/45%) | Moved behavioral health resources to hallway bins to make more visible and accessible for patients and PCPs (December 2017) | |

| Medical assistants began depression screening for all PCPs (September 2017 to May 2018) | ||

| Added monthly depression screening rate to bottom of weekly tip emails (December 2017) | ||

| Posted depression screening rate graph in PCG (May 2018) | ||

| The PCG has a sufficient number of BMED specialists on site (28%/12%) | Increased recruitment efforts for full-time health psychologist (July 2017) | |

| The clinic systematically tracks the progress of behavioral health treatment (30%/34%) | Email sent to PCP if appointment not scheduled for patient referred to psychiatry (August 2016 to October 2016, March 2017 to May 2017) | |

| Psychiatry notes desensitized (May 2018) | ||

| BMED is integrated into the workflow of the clinic (69%/71%) | Updated and disseminated BMED promotional and informational materials (October 2017, February 2018, April 2018) | |

| All clinic staff receive integrated care training (26%/31%) | PCG-BHIP update presentation at faculty and staff meetings (February 2018) | |

| Behavioral health training session at PCG annual retreat (February 2018) | ||

| PCPs and BMED specialists provide training for each other and the rest of the clinic staff (56%/59%) | Updated existing CDS tools and posted in workroom and clinic areas (November 2017 to December 2017) | |

| Opioid training at clinic staff meeting (December 2017) | ||

| Developed and distributed CDS tools for anxiety (February 2018) and ADHD (March 2018) in response to provider requests | ||

| Clinical practice | PCPs and BMED specialists do “warm handoffs” according to patient needs (70%/78%) | Weekly tip email about warm handoffs (December 2017) |

| BMED specialists are readily available to see patients and consult with PCPs in the clinic (37%/38%) | Increased recruitment efforts for full-time health psychologist (July 2017) | |

| BMED specialists take part in PCG clinic meetings (40%/48%) | Director of Health Psychology joins internal medicine section meetings (November 2017) | |

| PCPs and BMED specialists regularly consult about patient care in the clinic (65%/75%) | PCPs and psychologists colocated (continuous) | |

| PCPs and BMED specialists collaborate in making decisions about mutual patients in the clinic (72%/80%) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; BHIP, Behavioral Health Integration Program; BMED, behavioral medicine; CDS, clinical decision support; EHR, electronic health record; PCG, Primary Care Group; PCP, primary care physician.

Systems Integration

During the 2 years of this study, the systems integration domain score increased between 6 and 30 months (P = 0.01) (Table 1).

Because systems integration was the lowest scoring domain in the 6-month survey, most QI efforts were directed in this domain for the following 12 months. In an effort to integrate BMED into clinic workflow, flyers were updated, brochures were redesigned for patients and PCPs, and a referral flow diagram was included in weekly tip emails sent to all providers and staff. To increase BMED access, funding was secured to hire a full-time health psychologist and the number of BMED appointment slots was increased.

Depression screening also was an area of focus, as an important component of systems integration is the systematic detection of BH needs. Health information technology staff assisted with development of a passive annual reminder in the electronic health record (EHR) that linked to an electronic version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ).16 Physicians were incentivized to attend to the reminder by the public reporting of physician-level screening rates via email for 1 year to encourage social comparison.17 Although this improved screening rates, many patients still were not screened. Thus, a new process was piloted in which MAs would administer the PHQ-2.

Work also was done to improve tracking of patients’ BH treatments by monitoring psychiatry referrals and informing PCPs of incomplete referrals. Furthermore, PCP access to BH resources was increased by creating EHR smart phrases for easy insertion of BH educational content and resources into after-visit summaries.

The systems integration domain score increased between 6 and 18 months (P = 0.08), with higher ratings, albeit nonsignificant, for nearly all domain items (Table 1). The most improved item was agreement that BMED is integrated into clinic workflow, which increased from 55% to 70% (P = 0.15). Other improved items were: “treatment plans reflect an integrated approach” (40%–59%; P = 0.08) and “sufficient number of BMED specialists” (17%–28%; P = 0.20). There also were improvements in “triaging” (26%–38%; P = 0.24) and “detecting and serving” BH needs (26%–37%; P = 0.28), and “tracking the progress of BH treatment” (22%–32%; P = 0.30). Two items decreased in agreement: “Clinic scheduling system allows… same day appointments with BMED,” (22%–18%; P = 0.60) and “Integrated care… is supported by a viable financial system” (14%–12%; P = 0.77).

Because systems integration remained the lowest scoring domain at 18 months, efforts continued to be focused in this domain for the next 12 months. BMED promotion continued with updated clinic flyers and distribution of brochures to new faculty and residents. The search for a full-time health psychologist continued. Because the MA-administered depression screening pilot was successful, hospital leadership was convinced to allow MAs to administer the PHQ and enter results in the EHR. To encourage participation, a graph of monthly screening rates was posted in clinic and screening rates were included in each weekly tip email. Depression screenings increased from 18% to 58% after screening responsibilities were transferred to MAs.

Changes were made to the EHR and clinic workflow to improve systems integration. After gaining buy-in from the psychiatry department, the default setting for psychiatry notes (excluding psychotherapy notes) was changed to be viewable by other clinicians. BH smart phrases continued to be updated to include a broader range of topics and BH resources were placed in clinic hallways accessible to patients and physicians.

There was a marginal change in the systems integration domain score between 18 and 30 months (P = 0.56) (Table 1), but there were improvements in specific items. The most improved item was “treatment plans reflect an integrated approach,” which increased from 58% agreement to 90% (P = 0.001). There were increases in the nonsignificant ratings for “systematic triaging” of BH needs (38%–57%; P = 0.08), “detecting and serving” BH needs (37%–45%; P = 0.43), and “tracking the progress of BH treatment” (32%–34%; P = 0.81). Perceptions that BMED was well integrated into clinic workflow remained high (69%–71%; P = 0.89), while agreement with viable financial support remained low (12%–17%; P = 0.56). Fewer people agreed there were a sufficient number of BHPs (28%–12%; P = 0.05), and the perceived ability to schedule patients for same-day BMED appointments was unchanged (18%–26%; P = 0.34). Confidence that “patients… referred to BMED will be scheduled an appointment” decreased as well (42%–31%; P = 0.34). Using free-text responses, physicians consistently reported an insufficient number of BH specialists to meet their patients’ needs.

Training

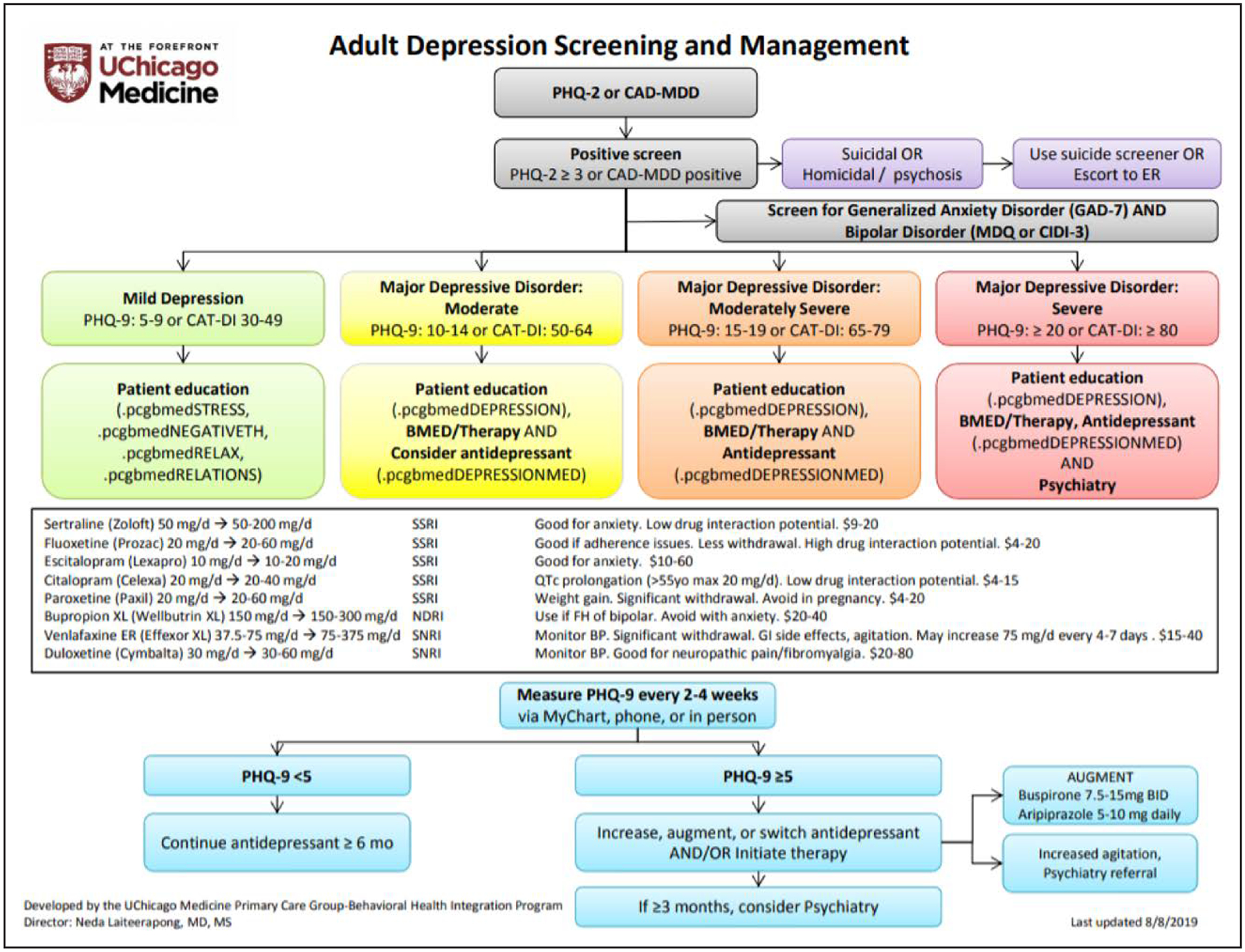

Between 6 and 30 months, there was a nonsignificant increase in the training domain score (P = 0.07) (Table 1). As this was the second lowest rated domain at 6 months, regular dissemination of information and training were initiated. Biannual updates on integration efforts, goals, and time lines were given during clinical operations and faculty section meetings by the PCG Associate Director of PCBH Integration (NL) and Director of Health Psychology (NB). The team developed clinical decision support (CDS) tools on depression (Figure), suicide, and panic disorder that were sent in weekly tip emails and posted in physician work areas, clinic rooms, and online. Each tool included a validated screener, guidance on interpreting results, treatment recommendations, medication options (if appropriate), and recommended follow-up intervals. Weekly tip emails continued to be sent and included information about BH management and community BH resources. The BMED team gave lectures to residents on assessment and management of anxiety and mood disorders.

Figure.

Adult depression screening and management clinical decision support tool. *.pcgbmed text refers to electronic health record smart phrases (brief text that links automatically to much longer preset text) that provide introductory patient-facing health psychology education materials. Abbreviations: BID, twice a day; BMED, behavioral medicine; BP, blood pressure; CAD-MDD, computerized adaptive diagnostic-major depressive disorder; CAT-DI, computerized adaptive test-depression inventory; CIDI-3, World Health Organization Compositive International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0; ER, emergency room; FH, family history; GI, gastrointestinal; MDQ, mood disorder questionnaire; mg, milligram; NRDI, norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; QTc, corrected QT interval; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There was nonsignificant improvement (P = 0.07) in training domain score at 18 months (Table 1). Most items improved slightly. The most improved item was “PCPs and BMED specialists provide training for each other…” from 40% at 6 months to 56% at 18 months (P = 0.13). Other items that showed nonsignificant improvement included PCPs and BMED specialists “attend trainings together” (16%–27%; P = 0.21) and “learn from each other” (71%–74%; P = 0.76). There was no change in “All clinic staff receives integrated care training” (26%–27%; P = 0.93).

However, training remained a low-scoring domain at the 18-month survey. For the next 12 months, updates were provided at staff meetings, and psychologists provided training for PCPs at meetings and clinic retreats. One PCG-BHIP team member (MA) led a training session on chronic pain and opioid use for all clinic staff. Finally, existing CDS tools on depression, panic, and suicide were updated, and new algorithms for anxiety and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were created.

Even with these efforts, the training domain score was the same between 18 and 30 months (P = 0.98; Table 1), although there were nonsignificant improvements for some items. The most improved item was “PCPs and BMED specialists attend trainings together” (27%–41%; P = 0.18). There were small increases in PCPs and BMED specialists “provide training for each other” (56%–59%; P = 0.79) and “learn from each other” (74%–79%; P = 0.59), and “all clinic staff receives integrated care training” (27%–31%; P = 0.70).

Integrated Clinical Practices

The integrated clinical practices domain score increased marginally between 6 and 30 months (P = 0.08) (Table 1).

Between 6 and 18 months, the number of BMED clinic sessions was increased to foster communication and collaboration between PCPs and psychologists. The names of psychologists and their clinic hours were added to all weekly tip emails and clinic flyers. A half-day educational experience for residents was launched, in which they conducted joint visits with BMED faculty and received individualized coaching on BH assessments, action planning, and communication.

The perception of integrated practices did not improve from 6 to 18 months (P = 0.26; Table 1), although there was nonsignificant improvement in some items. The most improved item was “PCPs and BMED specialists regularly consult about patient care,” from 46% to 66% (P = 0.06). Another improved item was that they “collaborate in making decisions about mutual patients,” from 58% to 73% (P = 0.13). However, agreement with “BMED specialists are readily available to see patients and consult with PCPs…” declined from 48% to 39% (P = 0.39).

For the next 12 months, psychologists and PCPs continued to be collocated in the same workroom and psychologists continued to attend clinical operations and faculty section meetings. PCPs were encouraged to do warm handoffs through reminders at faculty meetings and weekly tip emails.

These interventions had few effects at 30 months (P = 0.79) (Table 1). Some items improved nonsignificantly; for example, there were increases in agreement that providers “regularly consult about patient care” (65% at 18 mo to 75% at 30 mo; P = 0.37) and “collaborate in making decisions about mutual patients” (73%–80%; P = 0.47).

Other Domains

Although the target was to improve the 3 lowest scoring survey domains, there were improvements in other domains. The domain of beliefs and commitment improved between 6 and 18 months, and between 18 and 30 months (6 versus 30 mo; P = 0.03) (Table 1). The domain of interdisciplinary alliance rose between 6 and 18 months, and between 18 and 30 months (6 versus 30 mo; P = 0.02) (Table 1). Changes in leadership domain scores were not different at 6 months, at 18 months (6 versus 18 mo; P = 0.45), and at 30 months (6 versus 30 mo; P = 0.66) (Table 1).

Overall

Compared to 6 months, the overall integration score was higher at 18 months (P = 0.07) and at 30 months (P = 0.02) (Table 1). Overall scores did not differ significantly between providers and staff at 18 or 30 months. However, at 18 months, providers scored significantly higher in the domains of interdisciplinary alliance and leadership. Satisfaction with the progress of integration increased from 56% at 6 months to 71% at 18 months and 86% at 30 months (P = 0.01).

Discussion

Although numerous studies have reported the benefits of integrating BH care into primary care, few have described the steps to do so. A previous paper13 discussed the initial implementation of PCBH in this primary care clinic. The current study documents the process of growing and improving the integrated BH program for an additional 2 years. A validated survey measure was used to assess the level of integration in the clinic each year, identify areas that needed the most improvement, and focus efforts on improving those domains.

Much of the focus during these 2 years was to increase detection of BH problems and to educate physicians about BH problems and their treatments. The process of implementing systematic depression screening was challenging because it required engagement and buy-in from multiple stakeholders—IT, hospital leadership, clinic staff, and physicians. However, by establishing these connections, a framework was created with which to systematically identify patients with any number of BH problems. Similarly, the development of the first CDS tool for depression was time-intensive because different formats and content were trialed. But based on that experience, developing subsequent CDS tools was much easier, and there are now 10 CDS tools for common BH problems.

As awareness and identification of BH issues increased without a matching increase in BHPs, physicians were left without a direct BH resource to provide their patients. This imbalance severely limited integration efforts, and many physicians expressed frustration with the lack of BH appointment availability for their patients. Although a position for a full-time faculty BH psychologist was posted, it took time to find a health psychologist who met the job description, which is unsurprising because many BH staff are not trained to work in integrated settings.11 Recognizing that the internal capacity at UCM to provide psychotherapy services likely will remain unable to meet demand, partnerships with community BH resources have been aggressively pursued. Future analyses will explore changes in consultation and patient appointment wait times for BH services over time.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. It was implemented at an urban academic medical center; therefore, the interventions may not be generalizable to other practice settings. However, the use of a survey instrument to assess integration success is generalizable. Response bias is a potential limitation if respondents who prioritize integration are more likely to respond; however, a high response rate was achieved. This study had no control group who did not receive the intervention, which limits the ability to assess causality or account for secular trends. The survey also did not include items regarding opportunity costs and trade-offs with the implementation of PCBH; therefore, this was not assessed. Finally, patient outcomes were not measured. Based on the literature, the expectation is that the PCBH model will increase patient likelihood of engaging in BH care and attending primary care appointments,18 as well as reduce costs for patients, increase patient satisfaction, and increase clinic revenue.19 However, there are few robust studies testing how the PCBH model impacts patient outcomes.20 The authors plan to continue integration efforts and evaluate patient outcomes in future studies. Sustainability of the program is supported by its integration into health IT, its contribution to improvement of clinic QI measures, and financial reimbursements from the BMED clinic.

Conclusions

This study describes the process of implementing PCBH into a clinic. Using a validated survey instrument to evaluate level of integration, areas for improvement were identified, including systematic screening for depression, tools to aid PCPs in providing BH care, and availability of BMED appointments. Although successes were achieved increasing identification of patients with BH needs and expanding BH resources, insufficient BH personnel to meet the needs of patients was the major factor limiting further integration.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by an Innovation Grant from the University of Chicago Medicine’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness. Survey data were collected and managed through REDCap, which is hosted by the University of Chicago Medicine’s Center for Research Informatics and funded by the Institute for Translational Medicine/Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program (National Institutes of Health [NIH] UL1 TR000430).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.AJMQonline.com).

References

- 1.Wang PS, Demler O, Olfson M, et al. Changing profiles of service sectors used for mental health care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1187–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop TF, Seirup JK, Pincus HA, et al. Population of US practicing psychiatrists declined, 2003–13, which may help explain poor access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:1271–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, et al. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shim R, Rust G. Primary care, behavioral health, and public health: partners in reducing mental health stigma. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:774–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crowley RA, Kirschner N; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. The integration of care for mental health, substance abuse, and other behavioral health conditions into primary care: executive summary of an American College of Physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:298–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross KM, Klein B, Ferro K, et al. The cost effectiveness of embedding a behavioral health clinician into an existing primary care practice to facilitate the integration of care: a prospective, case-control program evaluation. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;26:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balasubramanian BA, Cohen DJ, Jetelina KK, et al. Outcomes of integrated behavioral health with primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty AM, Gayle C, Morgan-Jones R, et al. Improving quality of diabetes care by integrating psychological and social care for poorly controlled diabetes: 3 dimensions of care for diabetes. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2016;51:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller-Matero LR, Dykuis KE, Albujoq K, et al. Benefits of integrated behavioral health services: the physician perspective. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34:51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiter JT, Dobmeyer AC, Hunter CL. The Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model: an overview and operational definition. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25:109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrano N, Cordes C, Cubic B, et al. The state and future of the primary care behavioral health model of service delivery workforce. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25:157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwan BM, Valeras AB, Levey SB, et al. An evidence roadmap for implementation of integrated behavioral health under the Affordable Care Act. AIMS Public Health. 2015;2:691–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staab EM, Terras M, Dave P, et al. Measuring perceived level of integration during the process of primary care behavioral health implementation. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33:253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauth J, Tremblay G. The Integrated Care Evaluation Project: Full Report. Antioch University; New England; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin I, Wan W, Staab EM, et al. Use of report cards to increase primary care physician depression screening. J Gen Intern Med. Published online ahead of print July 23, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06065-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Possemato K, Johnson EM, Beehler GP, et al. Patient outcomes associated with primary care behavioral health services: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;53:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christian E, Krall V, Hulkower S, et al. Primary care behavioral health integration: promoting the Quadruple Aim. N C Med J. 2018;79:250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter CL, Funderburk JS, Polaha J, et al. Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model research: current state of the science and a call to action. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25:127–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.