Abstract

The growth and maturation of oocyte is accompanied by the accumulation of abundant RNAs and posttranscriptional regulation. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent epigenetic modification in mRNA, and precisely regulates the RNA metabolism as well as gene expression in diverse physiological processes. Recent studies showed that m6A modification and regulators were essential for the process of ovarian development and its aberrant manifestation could result in ovarian aging. Moreover, the specific deficiency of m6A regulators caused oocyte maturation disorder and female infertility with defective meiotic initiation, subsequently the oocyte failed to undergo germinal vesicle breakdown and consequently lost the ability to resume meiosis by disrupting spindle organization as well as chromosome alignment. Accumulating evidence showed that dysregulated m6A modification contributed to ovarian diseases including polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), ovarian aging and other ovarian function disorders. However, the complex and subtle mechanism of m6A modification involved in female reproduction and fertility is still unknown. In this review, we have summarized the current findings of the RNA m6A modification and its regulators in ovarian life cycle and female ovarian diseases. And we also discussed the role and potential clinical application of the RNA m6A modification in promoting oocyte maturation and delaying the reproduction aging.

Keywords: m6A, ovary, oocyte, meiotic, reproduction aging

1 Introduction

RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation was firstly reported in 1974 (Desrosiers et al., 1974; Perry and Kelley, 1974). Until 2011, the invention of m6A-specific methylated RNA immunoprecipitation with next-generation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) provided technical support for revealing the role of m6A methylation in eukaryotes (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012). m6A is the most prevalent internal modification in mRNA, non-coding RNA, ribosomal RNA, polyadenylated RNA (Krug et al., 1976; Rottman et al., 1976; Schibler et al., 1977; Fu et al., 2014; Meyer and Jaffrey, 2014), and it is composed of 0.1%–0.4% adenylate residues, most of which occurs on ‘RRACH’ (R = G or A; H = A, C or U) consensus sequence (Narayan and Rottman, 1988; Csepany et al., 1990). The m6A modification mainly enrich in the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTR), stop codons and last exon.

m6A modification has become an important branch of epigenetics independent of DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin rearrangement and non-coding RNA regulation. m6A precisely regulated the RNA metabolism and gene expression including pre-mRNA processing, transport, localization, splicing, stability, degradation and translation of RNA (Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2016; He and He, 2021; Liu and Zhou, 2021), and played an important role in embryonic development, tumor occurrence, organ development and other post-transcriptional regulation in biological or pathological processes (Atlasi and Stunnenberg, 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2019).

The m6A modifications are reversible and dynamically regulated by the m6A modulators. The formation of m6A is catalyzed by methyltransferase (METTL3/METTL14, WTAP, KIAA1429, RBM15 A/B, ZC3H13, and HAKAI) (Liu et al., 2014; Ping et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2014), and erased by demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5) (Jia et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2013). m6A can be recognized by readers, such as YTH-domain family proteins (YTHDFs), YTH domain-containing proteins (YTHDC1/2), IGFBP1/2/3, HNRNPs, eIF3, LRPPRC, and Prrac2 (Xu et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Du et al., 2016; Arguello et al., 2017; Patil et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021a).

2 m6A Methylation Modification in Female Reproductive Development and Aging

2.1 m6A Methylation in Development and Aging

2.1.1 m6A Methylation in Differentiations and Development

Many studies have confirmed that the differentiation and development of organs and tissues are precisely regulated by m6A modification accurately. For example, m6A played a decisive role on cell fate during the endothelial-to-haematopoietic transition to specify the earliest haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells during zebrafish embryogenesis, which was blocked in METTL3 deficient embryos (Zhang et al., 2017). The downregulation of ALKBH5 was responsible for the cardiomyocyte fate determination of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) originated from mesoderm cells (Han et al., 2021). Currently, m6A modification in neuromuscular system development has been clarified in many studies. METTL3/METTL14, ALKBH5, FTO, YTHDF1/2/3 participated in the development, and disorders of nervous system (Li et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2021). The silence of FTO disturbed the skeletal muscle differentiation by suppressing mitochondria biogenesis and energy production involved in mTOR-PGC-1a pathway (Wang et al., 2017). m6A and its regulators participated in the proliferation and differentiation of myoblast, as well as muscle regeneration (Li J. et al., 2021).

In reproductive system, m6A methylation is involved in the entire process of spermatogenesis, including mitosis, meiosis, and spermiogenesis (Fang et al., 2021; Gui and Yuan, 2021). Knockdown of circGFRα1 mediated by METTL14 in female germline stem cells (FGSCs) significantly reduced their self-renewal (Li X. et al., 2021). Some enzymes were found to be involved in the oocyte development, such as METTL3 (Xia et al., 2018; Sui et al., 2020; Mu et al., 2021), YTHDC1 (Kasowitz et al., 2018), KIAA1429 (Hu et al., 2020) and YTHDF2 (Ivanova et al., 2017). However, there are few studies on m6A methylation modification about ovarian development.

2.1.2 m6A Methylation in Aging/Senescence

Most studies showed m6A sites gradually increased with the aging process (Shafik et al., 2021). Abnormal m6A modification may be related to organ aging or cell senescence. Osteoporosis is a bone aging disease. m6A modification have been reported to be involved in regulating the proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of bone-related cells including bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts by multiple studies (Huang et al., 2021) (Wang et al., 2021b; Chen et al., 2022) (Wu et al., 2020). In addition, IGF2BP2 highly expressed in Alzheimer’s patients by bioinformatic analysis using multiple RNA-seq datasets of Alzheimer’s brain tissues (Deng et al., 2021). Su et al. found that age difference impacted m6A RNA methylation in hearts and their response to acute myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury (Su et al., 2021). To date, increasing research have reported the connection between m6A and organ aging/cell senescence. However, most of them mainly focused on methyltransferase, such as METTL3/METTL14 (Zhang J. et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022), and the demethylases and readers were gradually concerned in recent years, including ALKBH5 (Li et al., 2022a), WTAP (Li et al., 2022b), IGF2BP2 (Deng et al., 2021). Notedly, in reproductive aging, FTO has been shown to play the regulatory role (Ding et al., 2018; Zhou L. et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). Meanwhile, m6A modification-related key downstream or upstream proteins have not been deeply studied.

2.2 The Role of m6A in Ovarian Development and Function

A few studies have been reported to prove that m6A played an important regulatory role in regulating ovarian development, ovarian function disorders and ovarian aging. In addition, m6A also affected the oocyte maturation, embryonic development, early organ formation and pregnancy process. Here, we mainly summarized current progress in the studies of m6A involved in oocyte development and maturation, ovarian function maintaining and highlighted its continuous and multiple influence in female reproduction and fertility.

Sexual differentiation began from 5 weeks after fertilization to 20 weeks in gestation. Primary sex cord (PSC) development from the gonadal ridge originated from the urogenital ridge and incorporated primordial germ cells (PGC) in XX genotype, which migrated into the gonad from the wall of the yolk sac. PSCs extended into the medulla and formed the rete ovary, which eventually deteriorated. The ovaries originally developed within the abdomen but later underwent a relative descent into the pelvis as a result of disproportionate growth (Dudex, 2013).

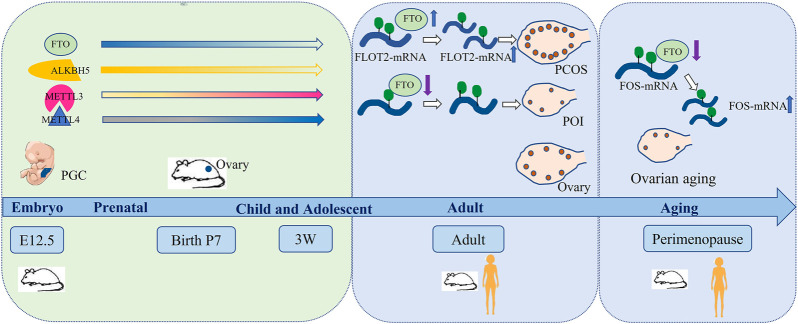

Recent studies showed that RNA methylation was involved in the ovarian development process. Sun et al. systematically analyzed the m6A level in ovaries, testes and detected the expression levels of several modification enzymes at different stages. They found that decreased demethylase (FTO and ALKBH5) and increased methyltransferase (METTL3 and METTL14) raised the m6A level during the development of gonads from 12.5 dpc as well as 7dpp to adult. In addition, m6A content was higher in luteal phase than follicular phase (Sun et al., 2020). Some regulators were uniquely and highly expressed in gonads. The expression of METTL3 was higher in ovaries and tests than other organs in Zebrafish (Xia et al., 2018). Moreover, the m6A regulated Sxl to facilitate sex determination in Drosophila (Kan et al., 2017). Currently, the mechanism of m6A is involved in gonadal development is not fully understood.

Ovarian aging is characterized by the constant decreasing of the number and the quality of follicles (Figure 1). The number of primordial follicles peaked at nearly seven million at gestational week 20 but dropped to one million at birth. At the menopausal age of 50 years old, about 1,000 follicles remained in ovary (Jerome and Robert, 2017; Laisk et al., 2019). Moreover, the more erroneous rate of meiosis during oocyte maturation increased with aging (Greaney et al., 2018). The aneuploidy rate of oocytes was 20% at the age of 35 and up to 60% at the age of 45 (Kuliev et al., 2011; Franasiak et al., 2014), resulting in the increasing incidence of aneuploid embryos, accompanied rising miscarriage, birth defection rate, gestational and obstetric complications (Hassold and Hunt, 2001; Frederiksen et al., 2018; Laisk et al., 2019; Correa-de-Araujo and Yoon, 2021). m6A modification and its regulators were essential for ovarian development and its aberrant manifestation resulted in ovarian aging. Jiang et al. found that downregulated FTO and increased m6A in granulosa cells (GCs) were accompanied by ovarian aging. They also reported that FTO slowed down the degradation of FOS-mRNA to upregulate FOS expression in GCs, eventually resulted in GC-mediated ovarian aging (Jiang et al., 2021). In 2009, FTO mutation was reported to cause severe growth retardation and accelerate senescence in the skin fibroblasts (Boissel et al., 2009). Meanwhile, Min et al. identified inconsistent results of m6A level during the aging process, which may be related to the tissue differences between the ovary and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Min et al., 2018).

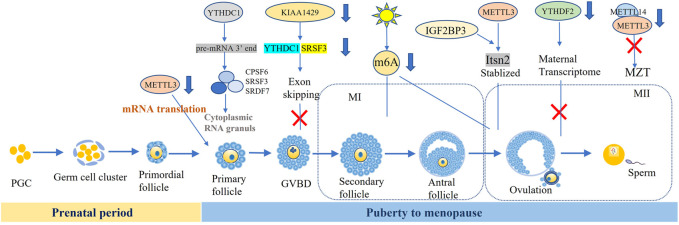

FIGURE 1.

m6A and regulators participate in the oocyte development and matruration.

However, the expression pattern of m6A methyltransferase and reader in ovarian aging process have not been fully evaluated. Moreover, we don’t know the significance of m6A content and changes of its regulators as well as how to promote ovarian development. In the future, the significance of m6A and its regulators in the regulation of ovarian life cycle should be further studied.

2.3 m6A in Oocyte Development and Maturation

The process of oogenesis included three phases: growth, maturation, and ovulation. Maternal mRNA is activated in the early stage of oocytes and ceased at the germinal vesicle (GV) stage. The accumulated mRNA was pivotal for self-development of oocyte, post fertilization and early embryonic protein synthesis. Germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) was usually regarded as a hallmark of the progress of oocyte maturation. Then, the maternal mRNA began to degrade after LH peaks, and most polyadenylate mRNA disappeared before ovulation. At the two-cell stage, abundant maternal mRNA degraded. Sui et al. found that the signaling of m6A modification gradually decreased with degraded maternal RNAs in the cytoplasm from GV to two-cell stage. Conversely, this trend was opposite from two-cell to blastocyst stage (Sui et al., 2020).

mRNA from stable to unstable was an important step in oocyte cytoplasmic maturation and zygote transition. These indicated that post transcriptional regulation of mRNA methylation played a key role in oocyte maturation and zygote transformation. Here we summarized the roles of m6A modification in the oocyte developmental, such as follicle selection, meiosis maturation, and maternal zygote transformation (MZT).

2.3.1 m6A Participated in the Follicular Selection

Although the role of m6A in mammalian follicular recruitment and selection has not been reported, there was a preliminary study on follicular selection by Hy-line Brown hens. MeRIP-seq data showed that chicken follicular transcriptome on average contained 1.61 and 1.59 m6A peaks per methylated transcript in pre-hierarchical and hierarchical follicles, respectively, which suggested that m6A methylation dynamic modification regulated chicken follicular selection (Fan et al., 2019). While the follicular recruitment and dominance in mammals remained to be studied.

2.3.2 m6A Participated in the GV and GVBD Stages of Oocyte Development

Some researchers revealed that m6A methylation was involved in the arrest of GV stage oocyte, and METTL3 defection effected the development of GV oocyte. Recent study reported that METTL3 protein was indeed located in the oocyte nucleus at postnatal day (PD) 5 and 12, GV stage and granulosa cells. After knocking out METTL3 specifically in oocytes, the number of GV oocytes was significantly reduced, and the oocyte diameter of METTL3cKO also became obviously smaller compared with WT mice. The deletion of METTL3 mainly effected the process of growing follicle development rather than the transition of primordial follicles to the activated growing follicles. Next, the researchers identified that METTL3/IGF3BP3-m6A-Itsn2 signaling axis participated in the oocyte development (Mu et al., 2021). In addition, the oocyte of Ythdc1 fl/- Ddx4-Cre ovaries was blocked at the primary stage, characterized by one layer of granulosa surrounding the oocytes, caused by the massive alternative splicing defects in YTHDC1 deficiency oocytes (Kasowitz et al., 2018).

The alteration of m6A methylation resulted in GVBD failure. Under the action of gonadotropin, oocytes underwent GVBD, that was the conversion of the prophase of the first meiosis to the first meiotic process (G2-M) (Zhou C. et al., 2021). METTL3 expressed at all stages of the oocyte and primarily distributed in the oocyte nuclei and granulosa cells. Most oocytes from METTL3cKO mice could not undergo GVBD (Mu et al., 2021). Its homolog was identified as mettl3, Ime4, MT-A in Zebrafish, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Arabidopsis thaliana (Xia et al., 2018). Xia et al. reported that the arresting rate of primary growth stage (PG) oocytes was higher and full-grown (FG) stage follicles was significantly lower in Zmettl3m/m compared to WT respectively. The GVBD rate of these defective oocytes can be rescued by HCG and 17α-20β-DHP, which suggested that the competency of oocyte maturation was impaired by the mettl3 mutation (Xia et al., 2018). However, other study showed that GVBD rate was similar between GV oocyte microinjected with siRNA against METTL3, which suggested the meiosis resumption did not rely on METTL3 (Sui et al., 2020).

The KIAA1429-specific deficiency in oocytes resulted in female infertility with defective follicular development and GV oocytes failing to undergo GVBD, consequently losing the ability to resume meiosis. Loss of KIAA1429 could lead to abnormal RNA metabolism in GV oocytes by affecting the exon skipping events associated with oogenesis. KIAA1429 deletion caused the decreased localization of SRSF3 and YTHDC1 in the nucleus of oocytes, while enrichment of the SRSF3-binding consensus and YTHDC1-binding consensus were observed in the exon regions near the splicing sites (Hu et al., 2020).

At present, only some enzymes of m6A have been proved to be involved in GV and GVBD stages before meiosis, most of them have not been deeply studied. Therefore, the interaction between these adaptors and the factors related to oocytes development and the upstream and downstream target genes should be identified.

2.3.3 m6A Participated in the Meiosis of Oocyte Maturation

Oocyte maturation was the committed process in sexual reproduction, referring to the process from the double line stage in the meiosis I (MI) to the meiosis II (MII). Various research reported m6A methylation were involved in the oocyte maturation process. METTL3 knockout in mammals and plants were embryonic lethality (Wang et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015; Geula et al., 2015). Researchers microinjected the siRNAs against METTL3 to GV oocytes and found that the ratio of first polar body extrusion (PBE) was significantly decreased, although the similar GVBD rate implied no effect on meiotic resumption. In addition, obvious spindle abnormalities including elongated, wide-polar and short spindles were observed in about 50% of MII oocytes in METTL3 knockdown group (Sui et al., 2020). Recently, Mu et al. reported that MII oocytes were not produced in Mettl3 Gdf9−cKO mice, with only a small number of oocytes reached to the end of MI, and almost no first PBE occurring. Further, most of the oocytes from Mettl3Gdf9−cKO mice could not be fertilized to form zygotes or develop beyond the four-cell embryo stage (Mu et al., 2021), which may affect the mRNA translation efficiency involved in chromosome congression and spindle formation due to METTL3 knockdown during oocyte maturation in mice. Another study also demonstrated that total translation efficiency of maternal mRNA was decreased in METTL3 knockdown oocytes (Sui et al., 2020). Moreover, environmental factors such as constant light exposure reduced the oocyte maturation rate by reduced m6A fluorescence intensity (Zhang H. et al., 2020).

Current research focused on the function of METTL3 in oocyte maturation, by affecting the translation efficiency, disrupting mRNA stability and expression of genes on sex hormone synthesis. Besides, other enzymes of m6A modification involved in meiotic of oocytes maturation have not been fully identified. We hope to map the integral mechanism network of m6A participating in oocyte development to help diagnose the causes of follicular development disorders and provide possible intervention ideas.

2.4 m6A Participated in Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition

MZT referred to that most maternal RNAs were gradually degraded after fertilization and the zygotic genome started to govern the gene expression, which phenomenon existed in all animal species (Zhao et al., 2017). Maternal mRNA clearance and the zygotic genome activation maintained early embryonic development. There was high 87% similarity in Zebrafish and human genes, so it was widely used as a model animal in the oocyte maturation and embryonic development in the research of m6A. YTHDF2 defection caused MZT failure by decelerating the decay of m6A-modified maternal mRNAs and disturbing zygotic genome activation (Zhao et al., 2017). Another study also showed that conditional mutagenesis of YTHDF2 disturbed maternal function in regulating transcript dosage of MII oocytes and further damaged early zygotic development in mice (Ivanova et al., 2017). Deng et al. reported that YTHDF2 was vital early embryogenesis as it advanced maternal mRNA clearance in goat (Deng et al., 2020). Another reader, IGF2BP2, was reported that maternal deletion of it caused early embryonic arrest at the 2-cell-stage in mouse embryos (Liu et al., 2019). In addition, METTL3 knockdown induced that the overall translation efficiency of maternal mRNA in oocytes was reduced, which further inhibited oocyte maturation and eventually impeded zygotic genome activation and MZT by disturbing the degradation of maternal mRNAs in MII oocytes (Sui et al., 2020).

3 m6A Modification Contributes to Ovarian Diseases

3.1 m6A and Ovarian Aging

Ovarian aging generally includes normal ovarian aging (NOA) and pathological ovarian aging (Zhang et al., 2019). NOA is defined as the gradual decline of oocyte quantity and quality with aging until menopause. Pathological ovarian aging refers to primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). In 2018, we firstly reported that m6A content in POI patients and CTX induced POI mice was significantly higher than normal groups, and the mRNA and protein expression levels of demethylase FTO were significantly lower in the POI patients than control group, which may be responsible for the increased risk of POI (Ding et al., 2018). Next, we identified that CTX raised the m6A and methyltransferase levels and inhibited the expression of demethylases and effectors with concentration-dependent (Huang B. et al., 2019). We also found that the expression of FTO reduced and m6A content was increased (Sun et al., 2021). Li team further verified that the downregulation of FTO increased m6A modification of FOS-mRNA-3′UTR and upregulated the expression of FOS in GCs, eventually resulting in the ovarian aging (Jiang et al., 2021). Zhu et at found that melatonin supplementation could protect the human ovarian surface epithelial cells to antagonize ovarian aging by suppressing the pathway of ROS-YTHDF2-MAPK-NF-κB (Zhu et al., 2022).

The mechanism of ovarian aging and POI is involved in heredity, immunity, inflammation, energy metabolism and epigenetic modification (Figure 2). Although there were some literatures to elaborate that m6A was related to the occurrence of ovarian aging, more research should be conducted in m6A modification on ovarian aging and POI to clarify the pathogenic mechanism to build a complete mechanism-network.

FIGURE 2.

m6A and regulators participates in the ovarian life cycle.

3.2 m6A and PCOS

PCOS is characterized by ovulation disorder and hyperandrogenemia, which seriously affects women’s reproduction and long-term health, attacking for about 6–10% females (Cooney et al., 2017). Scholars reported in 2012 that IGF-like families (IGF2BP2 and IGFBP2) from cumulus cells in PCOS were abnormal expression (Haouzi et al., 2012). Recently, the authors reported that m6A may be involved in the occurrence of PCOS. Zhang et al. analyzed the m6A profile of luteinized GCs from normovulatory women and non-obese PCOS patients following controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and found that luteinized GCs of PCOS patients triggered the m6A level increased. Meanwhile, the methyltransferases (METTL3/METTL14) and demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5) were also elevated (Figure 2). They identified that m6A modification was reduced in FOXO3 mRNA from the luteinized GCs in PCOS patients. Interestingly, selectively knocking down m6A methyltransferases or demethylases did not change the expression of FOXO3 in the luteinized GCs of PCOS patients. It indicated that the regulation of FOXO3 by m6A modification in PCOS was abnormal (Zhang S. et al., 2020). Moreover, Zhou et al. found that FTO induced the dysfunctions of GCs by upregulating FLOT2, which might be involved in the pathophysiology of obesity PCOS (Zhou L. et al., 2021). In addition, multiple meta-analysis showed that rs9939609 polymorphism of FTO gene was associated with PCOS risk (Wojciechowski et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2017). However, it was still controversial.

4 Clinical Application Prospect of m6A and its Regulators in Ovarian Diseases

Up to know, the related research of m6A modification mainly focused on the basic research, but the related research in clinical transformation were very limited. We summarized potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets of m6A regulators related to ovarian diseases. Firstly, m6A regulators can be used as biomarkers to reflect gametogenesis disorders, and to achieve preventive treatment of infertility. For example, METTL3, YTHDC1 are possible markers of GV oocyte arrest and GVBD failure (Sui et al., 2020; Mu et al., 2021). KIAA1429 may be the signal of GVBD failure (Hu et al., 2020). Secondly, precise targeting genes such as METTL3 (Sui et al., 2020; Mu et al., 2021), KIAA1429, WTAP (Hu et al., 2020), ALKBH5, YTHDF2, YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 (Ivanova et al., 2017), FTO (Ding et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2021), may be used as the drugs to ensure normal gametogenesis and exert a better therapeutic effect on oocyte development and improving ovarian function. Finally, inhibitors and activators of m6A and its regulators as important treatment strategy have been studied and applied extensively in experimental animals. For instance, the inhibitors of FTO were identified including Rhein (Chen et al., 2012), EGCG (Wu et al., 2018), Entacapone (Peng et al., 2019), Meclofenamic acid (Huang et al., 2015), FB23(Huang Y. et al., 2019), R-2HG (Su et al., 2018), MO-I-500 (Zheng et al., 2014). Gossypolacetic acid (GAA) was reported as the inhibitor of LRPPRC (Zhou et al., 2019). More inhibitors and activators of m6A regulators displayed effective therapeutic role in animal disease models. In the future, ovarian related diseases treated with m6A regulators might be a promising treatment selection (Figures 1, 2).

5 Conclusion

Abnormal m6A methylation affected oocyte development and maturation by interfering chromosome/spindle assembly, affecting transcript cutting, translation and degradation, leading to granulosa cell apoptosis and jointly damaging ovarian function. The specific mechanism of m6A dynamic regulatory network in the female reproductive system still needs to be further studied. Many unknown areas may be involved in the ovary or oocyte development process, for example, the enhancer and R-loop in the genes modified by m6A. In conclusion, m6A and its regulators show important function of regulation in ovarian development and oocyte maturation and are potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets for developmental disorders of the oocytes and ovarian diseases.

Author Contributions

XS and BH conceptualized the study, XS prepared the figures, XS, JL, HL, and BH wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92168104, 82071720), Suzhou Talent Training Program (GSWS2020057, GSWS2020066), Suzhou introduce expert team of clinical medicine (SZYJTD201708).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Arguello A. E., Deliberto A. N., Kleiner R. E. (2017). RNA Chemical Proteomics Reveals the N6-Methyladenosine (m6A)-Regulated Protein-RNA Interactome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17249–17252. 10.1021/jacs.7b09213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlasi Y., Stunnenberg H. G. (2017). The Interplay of Epigenetic Marks during Stem Cell Differentiation and Development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 643–658. 10.1038/nrg.2017.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissel S., Reish O., Proulx K., Kawagoe-Takaki H., Sedgwick B., Yeo G. S. H., et al. (2009). Loss-of-function Mutation in the Dioxygenase-Encoding FTO Gene Causes Severe Growth Retardation and Multiple Malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85, 106–111. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Ye F., Yu L., Jia G., Huang X., Zhang X., et al. (2012). Development of Cell-Active N6-Methyladenosine RNA Demethylase FTO Inhibitor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17963–17971. 10.1021/ja3064149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Hao Y.-J., Zhang Y., Li M.-M., Wang M., Han W., et al. (2015). m6A RNA Methylation Is Regulated by MicroRNAs and Promotes Reprogramming to Pluripotency. Cell. Stem Cell. 16, 289–301. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Gong W., Shao X., Shi T., Zhang L., Dong J., et al. (2022). METTL3-mediated m6A Modification of ATG7 Regulates Autophagy-GATA4 axis to Promote Cellular Senescence and Osteoarthritis Progression. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 81, 87–99. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney L. G., Lee I., Sammel M. D., Dokras A. (2017). High Prevalence of Moderate and Severe Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. 32, 1075–1091. 10.1093/humrep/dex044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-De-Araujo R., Yoon S. S. (2021). Clinical Outcomes in High-Risk Pregnancies Due to Advanced Maternal Age. J. Women's Health 30, 160–167. 10.1089/jwh.2020.8860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csepany T., Lin A., Baldick C. J., Jr., Beemon K. (1990). Sequence Specificity of mRNA N6-Adenosine Methyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 20117–20122. 10.1016/s0021-9258(17)30477-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M., Chen B., Liu Z., Cai Y., Wan Y., Zhang G., et al. (2020). YTHDF2 Regulates Maternal Transcriptome Degradation and Embryo Development in Goat. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8, 580367. 10.3389/fcell.2020.580367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Zhu H., Xiao L., Liu C., Liu Y. L., Gao W. (2021). Identification of the Function and Mechanism of m6A Reader IGF2BP2 in Alzheimer's Disease. Aging (Albany NY) 13 (21), 24086–24100. 10.18632/aging.203652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers R., Friderici K., Rottman F. (1974). Identification of Methylated Nucleosides in Messenger RNA from Novikoff Hepatoma Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 3971–3975. 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding C., Zou Q., Ding J., Ling M., Wang W., Li H., et al. (2018). Increased N6‐methyladenosine Causes Infertility Is Associated with FTO Expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 233, 7055–7066. 10.1002/jcp.26507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., et al. (2012). Topology of the Human and Mouse m6A RNA Methylomes Revealed by m6A-Seq. Nature 485, 201–206. 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Zhao Y., He J., Zhang Y., Xi H., Liu M., et al. (2016). YTHDF2 Destabilizes m6A-Containing RNA through Direct Recruitment of the CCR4-Not Deadenylase Complex. Nat. Commun. 7, 12626. 10.1038/ncomms12626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudex Ronald. W. (2013). High-Yield: Embryology. Fourth Edition. Beijing, China: Peking University Medical Press. [M]. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Zhang C., Zhu G. (2019). Profiling of RNA N6-Methyladenosine Methylation during Follicle Selection in Chicken Ovary. Poult. Sci. 98, 6117–6124. 10.3382/ps/pez277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F., Wang X., Li Z., Ni K., Xiong C. (2021). Epigenetic Regulation of mRNA N6-Methyladenosine Modifications in Mammalian Gametogenesis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 27, gaab025. 10.1093/molehr/gaab025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franasiak J. M., Forman E. J., Hong K. H., Werner M. D., Upham K. M., Treff N. R., et al. (2014). The Nature of Aneuploidy with Increasing Age of the Female Partner: a Review of 15,169 Consecutive Trophectoderm Biopsies Evaluated with Comprehensive Chromosomal Screening. Fertil. Steril. 101, 656–663.e651. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen L. E., Ernst A., Brix N., Braskhøj Lauridsen L. L., Roos L., Ramlau-Hansen C. H., et al. (2018). Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes at Advanced Maternal Age. Obstet. Gynecol. 131, 457–463. 10.1097/aog.0000000000002504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Dominissini D., Rechavi G., He C. (2014). Gene Expression Regulation Mediated through Reversible m6A RNA Methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 293–306. 10.1038/nrg3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula S., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Dominissini D., Mansour A. A., Kol N., Salmon-Divon M., et al. (2015). m 6 A mRNA Methylation Facilitates Resolution of Naïve Pluripotency toward Differentiation. Science 347, 1002–1006. 10.1126/science.1261417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaney J., Wei Z., Homer H. (2018). Regulation of Chromosome Segregation in Oocytes and the Cellular Basis for Female Meiotic Errors. Hum. Reprod. Update 24, 135–161. 10.1093/humupd/dmx035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui Y., Yuan S. (2021). Epigenetic Regulations in Mammalian Spermatogenesis: RNA-m6A Modification and beyond. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 4893–4905. 10.1007/s00018-021-03823-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Xu Z., Yu Y., Cao Y., Bao Z., Gao X., et al. (2021). ALKBH5-mediated m6A mRNA Methylation Governs Human Embryonic Stem Cell Cardiac Commitment. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 26, 22–33. 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haouzi D., Assou S., Monzo C., Vincens C., Dechaud H., Hamamah S. (2012). Altered Gene Expression Profile in Cumulus Cells of Mature MII Oocytes from Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 27, 3523–3530. 10.1093/humrep/des325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Hunt P. (2001). To Err (Meiotically) Is Human: the Genesis of Human Aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 280–291. 10.1038/35066065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P. C., He C. (2021). m6 A RNA Methylation: from Mechanisms to Therapeutic Potential. Embo J. 40, e105977. 10.15252/embj.2020105977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Ouyang Z., Sui X., Qi M., Li M., He Y., et al. (2020). Oocyte Competence Is Maintained by m6A Methyltransferase KIAA1429-Mediated RNA Metabolism during Mouse Follicular Development. Cell. Death Differ. 27, 2468–2483. 10.1038/s41418-020-0516-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Ding C., Zou Q., Wang W., Li H. (2019a). Cyclophosphamide Regulates N6-Methyladenosine and m6A RNA Enzyme Levels in Human Granulosa Cells and in Ovaries of a Premature Ovarian Aging Mouse Model. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 415. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Xu S., Liu L., Zhang M., Guo J., Yuan Y., et al. (2021). m6A Methylation Regulates Osteoblastic Differentiation and Bone Remodeling. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 783322. 10.3389/fcell.2021.783322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Su R., Sheng Y., Dong L., Dong Z., Xu H., et al. (2019b). Small-Molecule Targeting of Oncogenic FTO Demethylase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 35, 677–691.e610. 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Yan J., Li Q., Li J., Gong S., Zhou H., et al. (2015). Meclofenamic Acid Selectively Inhibits FTO Demethylation of m6A over ALKBH5. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 373–384. 10.1093/nar/gku1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova I., Much C., Di Giacomo M., Azzi C., Morgan M., Moreira P. N., et al. (2017). The RNA M 6 A Reader YTHDF2 Is Essential for the Post-transcriptional Regulation of the Maternal Transcriptome and Oocyte Competence. Mol. Cell. 67, 1059–1067.e1054. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome S., Robert B. (2017). Yen & Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. Eighth Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences. [M]. [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Fu Y., Zhao X., Dai Q., Zheng G., Yang Y., et al. (2011). N6-methyladenosine in Nuclear RNA Is a Major Substrate of the Obesity-Associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 885–887. 10.1038/nchembio.687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.-x., Wang Y.-n., Li Z.-y., Dai Z.-h., He Y., Chu K., et al. (2021). The m6A mRNA Demethylase FTO in Granulosa Cells Retards FOS-dependent Ovarian Aging. Cell. Death Dis. 12, 744. 10.1038/s41419-021-04016-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan L., Grozhik A. V., Vedanayagam J., Patil D. P., Pang N., Lim K.-S., et al. (2017). The m6A Pathway Facilitates Sex Determination in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 8, 15737. 10.1038/ncomms15737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasowitz S. D., Ma J., Anderson S. J., Leu N. A., Xu Y., Gregory B. D., et al. (2018). Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates Alternative Polyadenylation and Splicing during Mouse Oocyte Development. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007412. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug R. M., Morgan M. A., Shatkin A. J. (1976). Influenza Viral mRNA Contains Internal N6-Methyladenosine and 5'-terminal 7-methylguanosine in Cap Structures. J. Virol. 20, 45–53. 10.1128/jvi.20.1.45-53.1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuliev A., Zlatopolsky Z., Kirillova I., Spivakova J., Cieslak Janzen J. (2011). Meiosis Errors in over 20,000 Oocytes Studied in the Practice of Preimplantation Aneuploidy Testing. Reprod. Biomed. Online 22, 2–8. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisk T., Tšuiko O., Jatsenko T., Hõrak P., Otala M., Lahdenperä M., et al. (2019). Demographic and Evolutionary Trends in Ovarian Function and Aging. Hum. Reprod. Update 25, 34–50. 10.1093/humupd/dmy031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Luo R., Zhang W., He S., Wang B., Liang H., et al. (2022a). m6A Hypomethylation of DNMT3B Regulated by ALKBH5 Promotes Intervertebral Disc Degeneration via E4F1 Deficiency. Clin. Transl. Med. 12, e765. 10.1002/ctm2.765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Ma L., He S., Luo R., Wang B., Zhang W., et al. (2022b). WTAP-mediated m6A Modification of lncRNA NORAD Promotes Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Nat. Commun. 13, 1469. 10.1038/s41467-022-28990-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Pei Y., Zhou R., Tang Z., Yang Y. (2021a). Regulation of RNA N6-Methyladenosine Modification and its Emerging Roles in Skeletal Muscle Development. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 17, 1682–1692. 10.7150/ijbs.56251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhao X., Wang W., Shi H., Pan Q., Lu Z., et al. (2018). Ythdf2-mediated m6A mRNA Clearance Modulates Neural Development in Mice. Genome Biol. 19, 69. 10.1186/s13059-018-1436-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Tian G., Wu J. (2021b). Novel circGFRα1 Promotes Self-Renewal of Female Germline Stem Cells Mediated by m6A Writer METTL14. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 640402. 10.3389/fcell.2021.640402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A. L., Xie H. J., Xie H. Y., Liu J., Yin J., Hu J. S., et al. (2017). Association between Fat Mass and Obesity Associated (FTO) Gene Rs9939609 A/T Polymorphism and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. Genet. 18, 89. 10.1186/s12881-017-0452-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. B., Muhammad T., Guo Y., Li M. J., Sha Q. Q., Zhang C. X., et al. (2019). RNA‐Binding Protein IGF2BP2/IMP2 Is a Critical Maternal Activator in Early Zygotic Genome Activation. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900295. 10.1002/advs.201900295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yue Y., Han D., Wang X., Fu Y., Zhang L., et al. (2014). A METTL3-METTL14 Complex Mediates Mammalian Nuclear RNA N6-Adenosine Methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 93–95. 10.1038/nchembio.1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Dai Q., Zheng G., He C., Parisien M., Pan T. (2015). N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA Structural Switches Regulate RNA-Protein Interactions. Nature 518, 560–564. 10.1038/nature14234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Li F., Lin J., Fukumoto T., Nacarelli T., Hao X., et al. (2021). m6A-independent Genome-wide METTL3 and METTL14 Redistribution Drives the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype. Nat. Cell. Biol. 23, 355–365. 10.1038/s41556-021-00656-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-M., Zhou J. (2021). Multifaceted Regulation of Translation by the Epitranscriptomic Modification N6-Methyladenosine. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 56, 137–148. 10.1080/10409238.2020.1869174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Chen C., Ji X., Liu J., Zhou Q., Wang G., et al. (2019). The Interplay between m6A RNA Methylation and Noncoding RNA in Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 121. 10.1186/s13045-019-0805-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. D., Jaffrey S. R. (2014). The Dynamic Epitranscriptome: N6-Methyladenosine and Gene Expression Control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 313–326. 10.1038/nrm3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K. D., Saletore Y., Zumbo P., Elemento O., Mason C. E., Jaffrey S. R. (2012). Comprehensive Analysis of mRNA Methylation Reveals Enrichment in 3′ UTRs and Near Stop Codons. Cell. 149, 1635–1646. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min K.-W., Zealy R. W., Davila S., Fomin M., Cummings J. C., Makowsky D., et al. (2018). Profiling of m6A RNA Modifications Identified an Age-Associated Regulation of AGO2 mRNA Stability. Aging Cell. 17, e12753. 10.1111/acel.12753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu H., Zhang T., Yang Y., Zhang D., Gao J., Li J., et al. (2021). METTL3-mediated mRNA N6-Methyladenosine Is Required for Oocyte and Follicle Development in Mice. Cell. Death Dis. 12, 989. 10.1038/s41419-021-04272-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P., Rottman F. M. (1988). An In Vitro System for Accurate Methylation of Internal Adenosine Residues in Messenger RNA. Science 242, 1159–1162. 10.1126/science.3187541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil D. P., Pickering B. F., Jaffrey S. R. (2018). Reading m6A in the Transcriptome: m6A-Binding Proteins. Trends Cell. Biol. 28, 113–127. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S., Xiao W., Ju D., Sun B., Hou N., Liu Q., et al. (2019). Identification of Entacapone as a Chemical Inhibitor of FTO Mediating Metabolic Regulation through FOXO1. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaau7116. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau7116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry R. P., Kelley D. E. (1974). Existence of Methylated Messenger RNA in Mouse L Cells. Cell. 1, 37–42. 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90153-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ping X.-L., Sun B.-F., Wang L., Xiao W., Yang X., Wang W.-J., et al. (2014). Mammalian WTAP Is a Regulatory Subunit of the RNA N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase. Cell. Res. 24, 177–189. 10.1038/cr.2014.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottman F. M., Desrosiers R. C., Friderici K. (1976). Nucleotide Methylation Patterns in Eukaryotic mRNA. Prog. Nucleic Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 19, 21–38. 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60906-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibler U., Kelley D. E., Perry R. P. (1977). Comparison of Methylated Sequences in Messenger RNA and Heterogeneous Nuclear RNA from Mouse L Cells. J. Mol. Biol. 115, 695–714. 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90110-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S., Mumbach M. R., Jovanovic M., Wang T., Maciag K., Bushkin G. G., et al. (2014). Perturbation of m6A Writers Reveals Two Distinct Classes of mRNA Methylation at Internal and 5′ Sites. Cell. Rep. 8, 284–296. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafik A. M., Zhang F., Guo Z., Dai Q., Pajdzik K., Li Y., et al. (2021). N6-methyladenosine Dynamics in Neurodevelopment and Aging, and its Potential Role in Alzheimer's Disease. Genome Biol. 22, 17. 10.1186/s13059-020-02249-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su R., Dong L., Li C., Nachtergaele S., Wunderlich M., Qing Y., et al. (2018). R-2HG Exhibits Anti-tumor Activity by Targeting FTO/m6A/MYC/CEBPA Signaling. Cell. 172, 90–105.e123. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X., Shen Y., Jin Y., Kim I.-m., Weintraub N. L., Tang Y. (2021). Aging-Associated Differences in Epitranscriptomic m6A Regulation in Response to Acute Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Female Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 654316. 10.3389/fphar.2021.654316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X., Hu Y., Ren C., Cao Q., Zhou S., Cao Y., et al. (2020). METTL3-mediated m6A Is Required for Murine Oocyte Maturation and Maternal-To-Zygotic Transition. Cell. Cycle 19, 391–404. 10.1080/15384101.2019.1711324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Zhang J., Jia Y., Shen W., Cao H. (2020). Characterization of m6A in Mouse Ovary and Testis. Clin. Transl. Med. 10, e141. 10.1002/ctm2.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Zhang Y., Hu Y., An J., Li L., Wang Y., et al. (2021). Decreased Expression of m6A Demethylase FTO in Ovarian Aging. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 303, 1363–1369. 10.1007/s00404-020-05895-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Chen L., Qiang P. (2021a). The Role of IGF2BP2, an m6A Reader Gene, in Human Metabolic Diseases and Cancers. Cancer Cell. Int. 21, 99. 10.1186/s12935-021-01799-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Fu Q., Yang J., Liu J. L., Hou S. M., Huang X., et al. (2021b). RNA N6-Methyladenosine Demethylase FTO Promotes Osteoporosis through Demethylating Runx2 mRNA and Inhibiting Osteogenic Differentiation. Aging (Albany NY) 13 (17), 21134–21141. 10.18632/aging.203377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Huang N., Yang M., Wei D., Tai H., Han X., et al. (2017). FTO Is Required for Myogenesis by Positively Regulating mTOR-PGC-1α Pathway-Mediated Mitochondria Biogenesis. Cell. Death Dis. 8–e2702. 10.1038/cddis.2017.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G. C., Yue Y., Han D., et al. (2014). N6-methyladenosine-dependent Regulation of Messenger RNA Stability. Nature 505, 117–120. 10.1038/nature12730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., Lu Z., Han D., Ma H., et al. (2015). N6-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell. 161, 1388–1399. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li Y., Yue M., Wang J., Kumar S., Wechsler-Reya R. J., et al. (2018). N6-methyladenosine RNA Modification Regulates Embryonic Neural Stem Cell Self-Renewal through Histone Modifications. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 195–206. 10.1038/s41593-017-0057-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojciechowski P., Lipowska A., Lipowska A., Rys P., Ewens K. G., Franks S., et al. (2012). Impact of FTO Genotypes on BMI and Weight in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetologia 55, 2636–2645. 10.1007/s00125-012-2638-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R., Li A., Sun B., Sun J.-G., Zhang J., Zhang T., et al. (2019). A Novel m6A Reader Prrc2a Controls Oligodendroglial Specification and Myelination. Cell. Res. 29, 23–41. 10.1038/s41422-018-0113-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R., Yao Y., Jiang Q., Cai M., Liu Q., Wang Y., et al. (2018). Epigallocatechin Gallate Targets FTO and Inhibits Adipogenesis in an mRNA m6A-YTHDF2-dependent Manner. Int. J. Obes. 42, 1378–1388. 10.1038/s41366-018-0082-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Shi Y., Lu M., Song M., Yu Z., Wang J., et al. (2020). METTL3 Counteracts Premature Aging via m6A-dependent Stabilization of MIS12 mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 11083–11096. 10.1093/nar/gkaa816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H., Zhong C., Wu X., Chen J., Tao B., Xia X., et al. (2018). Mettl3 Mutation Disrupts Gamete Maturation and Reduces Fertility in Zebrafish. Genetics 208, 729–743. 10.1534/genetics.117.300574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W., Adhikari S., Dahal U., Chen Y.-S., Hao Y.-J., Sun B.-F., et al. (2016). Nuclear M 6 A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell. 61, 507–519. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Wang X., Liu K., Roundtree I. A., Tempel W., Li Y., et al. (2014). Structural Basis for Selective Binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH Domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 927–929. 10.1038/nchembio.1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Hsu P. J., Chen Y.-S., Yang Y.-G. (2018). Dynamic Transcriptomic m6A Decoration: Writers, Erasers, Readers and Functions in RNA Metabolism. Cell. Res. 28, 616–624. 10.1038/s41422-018-0040-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., She Y., Ji S.-J. (2021). m6A Modification in Mammalian Nervous System Development, Functions, Disorders, and Injuries. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 679662. 10.3389/fcell.2021.679662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Chen Y., Sun B., Wang L., Yang Y., Ma D., et al. (2017). m6A Modulates Haematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Specification. Nature 549, 273–276. 10.1038/nature23883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Yan K., Sui L., Nie J., Cui K., Liu J., et al. (2020a). Constant Light Exposure Causes Oocyte Meiotic Defects and Quality Deterioration in Mice. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115467. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Ao Y., Zhang Z., Mo Y., Peng L., Jiang Y., et al. (2020b). Lamin A Safeguards the M6 A Methylase METTL14 Nuclear Speckle Reservoir to Prevent Cellular Senescence. Aging Cell. 19, e13215. 10.1111/acel.13215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Chen Q., Du D., Wu T., Wen J., Wu M., et al. (2019). Can Ovarian Aging Be Delayed by Pharmacological Strategies? Aging 11, 817–832. 10.18632/aging.101784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Deng W., Liu Q., Wang P., Yang W., Ni W. (2020c). Altered M 6 A Modification Is Involved in Up‐regulated Expression of FOXO3 in Luteinized Granulosa Cells of Non‐obese Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 24, 11874–11882. 10.1111/jcmm.15807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. S., Wang X., Beadell A. V., Lu Z., Shi H., Kuuspalu A., et al. (2017). m6A-dependent Maternal mRNA Clearance Facilitates Zebrafish Maternal-To-Zygotic Transition. Nature 542, 475–478. 10.1038/nature21355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Cox T., Tribbey L., Wang G. Z., Iacoban P., Booher M. E., et al. (2014). Synthesis of a FTO Inhibitor with Anticonvulsant Activity. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 5, 658–665. 10.1021/cn500042t [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Dahl J. A., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C.-M., Li C. J., et al. (2013). ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol. Cell. 49, 18–29. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Zhang X., Miao Y., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xiong B. (2021a). The Cohesin Stabilizer Sororin Drives G(2)-M Transition and Spindle Assembly in Mammalian Oocytes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg9335. 10.1126/sciadv.abg9335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Han X., Li W., Wang N., Yao L., Zhao Y., et al. (2021b). N6-methyladenosine Demethylase FTO Induces the Dysfunctions of Ovarian Granulosa Cells by Upregulating Flotillin 2. Reprod. Sci. 10.1007/s43032-021-00664-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Sun G., Zhang Z., Zhao L., Xu L., Yuan H., et al. (2019). Proteasome-Independent Protein Knockdown by Small-Molecule Inhibitor for the Undruggable Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18492–18499. 10.1021/jacs.9b08777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R., Ji X., Wu X., Chen J., Li X., Jiang H., et al. (2022). Melatonin Antagonizes Ovarian Aging via YTHDF2-MAPK-NF-Κb Pathway. Genes. & Dis. 9, 494–509. 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]