Abstract

Social distancing (SD) was an effective way of reducing virus transmission during the deadly and highly infectious COVID-19 pandemic. Using a prospective longitudinal design, the present study explored how the Big 5 traits relate to variations in SD in a sample of university students (n = 285), and replicated these findings using informant reports. Self-determination theory’s concepts of autonomous motivation and intrinsic community values were explored as potential mechanisms linking traits to SD. Individuals who were higher on trait agreeableness and conscientiousness engaged in more SD because they more effectively internalized the importance and value of the guidelines as a function of their concerns about the welfare of their communities. Informant reports confirmed trait agreeableness and conscientiousness to be associated with more SD. These results enhance our understanding of individual differences associated with better internalization and adherence to public health guidelines and can inform future interventions in similar crises.

Keywords: Big 5 personality traits, Self-determination theory, COVID-19 pandemic, Social distancing, Informant reports

The global COVID-19 pandemic, which at the time of writing this article has infected over 520 million people and claimed over 6 million lives worldwide, has led many governments to recommend that their citizens make behavioural changes to reduce the spread of the virus. In others words, people all over the world have been encouraged to adopt the “emergency goal” of social distancing, which involves making changes in our everyday routines in order to minimize close contact with others, such as avoiding crowded places and non-essential gatherings, limiting contact with people outside one’s household, keeping a distance of at least 2 arms lengths from others, and wearing a mask (when keeping 2 m distances from others is not possible). Research suggests that adhering to social distancing measures is effective in reducing the spread of the virus, resulting in lower numbers of new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths (Matrajt & Leung, 2020). While research suggests that social distancing is effective at flattening the curve, potentially saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of individuals, there is variation in how much individuals, or groups, agree with and adhere to social distancing measures. Since adhering to social distancing measures can have a large impact on the spread of the virus, an important research endeavor would be to explore personality and motivational factors that may predict adherence to social distancing measures.

A key factor that could be predictive of an individual’s likelihood of engaging in social distancing is the quality of their motivation. According to self-determination theory, the value and importance of an activity, such as social distancing, can be internalized for autonomous or controlled reasons (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Relatively more internalized purpose or rationale for behaviour is considered to be more autonomously motivated and the behaviour is seen by the actor as self-generated and pursued whole-heartedly because the individual “wants to” (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Within the context of the pandemic, this would mean the individual would engage in social distancing because they “want to” and have internalized the idea that it is an important and meaningful practice. In contrast, an individual is considered to have controlled motivation for a behaviours when its purpose or rationale is only partially internalized and the individual tends to feel alienated from its pursuit and will only pursue it because they “have to” (Ryan & Deci, 2017). In this case, individuals would feel guilty or anxious if they did not practice social distancing or would do so only in anticipation of external consequences (e.g., disapproval of others). Several decades of research has found that pursuing goal-directed behaviour for autonomous, rather than controlled, reasons is predictive of more sustained effort and goal progress (e.g., Koestner 2008; Koestner et al., 2008; Milyavskaya et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2021; Ryan & Deci 2017). The present study hypothesized that autonomous motivation for complying to the COVID-19 pandemic social distancing heath guidelines would be predictive of the extent to which individuals adhered to the guidelines.

Autonomous motivation is often mistaken as being synonymous with independence. Autonomous motivation is a highly personal form of motivation that highlights one’s desires and freedom of choice. However, recent research has found that autonomous motivation is a highly collaborative process and that dispositional characteristics that orient people towards cooperativeness with others is associated with an upward spiral of their autonomous motivation and progress in their goal-directed behaviours (Levine et al., 2020, 2021). In the present study, we hypothesized that certain personality characteristics that promote collaboration and cooperation with others would predispose an individual to better internalize and feel more autonomously motivated to adhere to the COVID-19 public health recommendations.

McAdams’ (2015) 3-tier model of personality suggests how personality characteristics may be related to adhering to guidelines. The first level of personality comprises one’s dispositional traits. Broadly speaking, personality traits are consistencies in social-emotional functioning, and are thought to be best captured by the Big 5 trait taxonomy: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, openness to experience and neuroticism (John & Srivastava, 1999). The second level is one’s personal concerns (i.e. one’s personal goals, projects, aspirations, and values). The third level of personality comprises an individual’s life narrative, which is essential for identity formation. While this third level could be relevant to the adherence and internalization of social distancing measures, it is outside the scope of the present study. Indeed, the present study will primarily focus on the first two levels of personality and explore how traits and values, in the form of self-determination theory’s community values (i.e. valuing helping those in your community and working towards the betterment of society), may relate to the internalization of the importance (i.e. autonomous motivation) of and actual adherence to social distancing measures. Since socially distancing within the context of the pandemic is to protect those in our communities who are most at risk, our hypothesis was that certain traits that orient people toward having greater concern for their community will be associated with greater autonomous motivation for and actual adherence to the social distancing guidelines. Oosterhoff et al., (2020) found that a sense of social responsibility and concerns over others becoming ill were the primary motivations endorsed by adolescents who engaged in social distancing, however, they did not explore the quality of this motivation (i.e. whether it is autonomous or controlled) nor the personality traits that would predispose someone to have these motivations.

Considering which of the Big 5 traits would orient an individual towards collaboration and therefore greater internalization of the COVID-19 pandemic protective health measures, agreeableness seems a likely candidate, and there is already emerging evidence to support this hypothesis (Zajenkowski et al., 2020). Individuals high on agreeableness are thought to be warm, friendly, and have a tendency toward pro-social behaviour. The data appear to show that the death rates for COVID-19 pandemic increase with age and with the presence of pre-existing conditions (Onder et al., 2020). This means that for younger individuals, such as the young adult participants who were recruited in the present study, a large part of the rationale for social distancing would be to care for and protect others in their community. As McAdams (2015) asserts, “agreeable people are more than nice. Agreeableness incorporates expressive qualities of love and empathy, friendliness, cooperation and care… [agreeableness] includes such concepts as altruism, affection and many of the most admirably humane aspects of the human personality”. Therefore, we hypothesized that high agreeableness would predispose an individual to care about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on others and to want to do their part to protect their communities by social distancing. More specifically, we hypothesized a path in which agreeableness is associated with greater concern for their community, leading to greater autonomous motivation for adhering to social distancing guidelines, which is subsequently associated with greater adherence.

Supporting our hypothesis, a recent study on the Big 5 traits and adherence to COVID-19 pandemic social distancing guidelines found agreeableness to be the only Big 5 trait associated with adhering to social distancing measures (Zajenkowski et al., 2020). One of the aims of the present study was to replicate and extend these findings using a longitudinal design by exploring whether an individual’s community values and level of internalization of the COVID-19 public health guidelines mediate the relation between the Big 5 traits and adherence to the social distancing guidelines. Moreover, we also aimed to replicate the findings linking traits to social distancing by using friend and family informant reports of participants’ personality and their perceptions of how much participants socially distanced.

Intuitively, conscientiousness, defined as being efficient, organized, dutiful, reliable and responsible, seems like a Big 5 trait that would be plausibly associated with being effective at adhering to public health guidelines aimed at reducing the spread of the virus (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Indeed, adhering to public health guidelines requires behaviours such as being vigilant at hand washing, wearing a mask and maintaining a 2-meter distance from those around you whenever possible. It requires you to remain responsible and limit contact with others outside of your household and not engage in non-essential travel - no matter how temping it might be! These are all behaviours for which being a highly conscientious person would likely be quite helpful. Even prior to the pandemic, a meta-analysis found conscientiousness to be positively associated with health promoting behaviours, such as diet and exercise, and negatively associated with risky health-related behaviours, such smoking and alcohol use (Bogg & Roberts, 2004). Furthermore, Ai et al., (2019) found that conscientious individuals tend to visit relatively fewer places in a day. Taken together, these findings suggest that social distancing, which is essentially a health promoting behaviour, is consistent with behaviours that conscientious individuals were already engaging in prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, according to Sheldon’s (2014) self-concordance model, when an individual engages in goal-directed behaviour (such as social distancing) that is more reflective of and is better supported by one’s underlying traits, interests, values, and motives, the individual will tend to feel more autonomous and be more likely to persist (Moore et al., 2020; Ryan, Sheldon et al., 1996). Therefore, we hypothesized that the trait of conscientiousness would be concordant with engaging in social distancing and will therefore be associated with greater autonomous motivation for and engagement in social distancing behaviours.

Besides trait conscientiousness being concordant with engaging in social distancing, would conscientiousness also predispose an individual to value their community? McAdams (2015) discusses how, even though agreeableness and conscientiousness are different traits, they do tend to be associated with similar important life outcomes, such as positive relationship outcomes and prosocial behaviours (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997; McAdams, 2015; Noftle & Shaver, 2006; Swickert et al., 2014). In addition, both agreeableness and conscientiousness are thought to develop out of the same developmental precursor – effortful control. Effortful control is a child temperament factor that consists of behaviours related to focusing attention and withstanding impulses so as to respond adaptively to situational demands (Li-Grining, 2007). Effortful control is thought to lead to the development of our “moral conscience” and is associated with key moral emotions such as empathy and a sense of moral responsibility – factors that would seem necessary for one to have a deep concern for the health and well-being of one’s communities (McAdams, 2015; Rueda, 2012). A concern that would likely lead one to social distance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, while we previously discussed a pathway from conscientiousness to social distancing through autonomous motivation due to the concordance of social distancing with trait conscientiousness, we would also hypothesize a similar pathway to the one outlined for agreeableness through their community values.

The present study

As evidenced by the large gatherings that took place during periods of confinement and by the anti-mask protests that have been reported in the media, there are variations in how much people have been willing to adhere to the recommended social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. The present study sought to explore the associations between personality and motivational factors and the extent to which individuals adhere to social distancing measures during the first wave of the pandemic. We hypothesized that individuals who were more autonomously motivated to social distance and those who highly valued supporting their community would be more likely to socially distance. In addition, we hypothesized that the Big 5 personality traits of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, which promote collaboration and cooperation with others, would orient individuals toward more community aspirations and would predispose individuals to better internalize and feel more autonomously motivated to comply with the COVID-19 health recommendations. Finally, we hypothesized that autonomous motivation for adhering to social distancing health guidelines and intrinsic community values would mediate the association between the personality traits and greater adherence. A methodological strength of the current investigation was that, in order to address the limitation of participant self-report bias, we also linked traits to social distancing using assessments of participants’ personality and social distancing behaviours via friend and family informant reports.

Methods

Participants and procedure

285 university students (83.2% female), aged 18 to 53 years (Mean = 20.7, SD = 3.80), were recruited to participate in a large 6-wave prospective study on personal goals and well-being. We aimed to recruit upwards of 250 participants in order to ensure enough power to detect small effects 80% of the time. When conducting a path analysis, the literature suggests a minimum sample of 200 (Kline, 2011). Overall, 47.4% of participants reported they were White, 38.6% reported Asian, 5.6% Middle eastern/Arab Canadian, 4.6% Latino-Hispanic, 3.5% Black/African, and less than 1% Native/First Nations. More than 80% of participants were retained across surveys.

Due to the focus of the present study being on the COVID-19 pandemic, only measures assessed at baseline (T1) and mid-second semester (T5) were relevant for consideration as it was at these time points that the variables of interest were assessed. Over the course of the study, participants completed online questionnaires via Qualtrics experimental software (Qualtrics, Inc. Salt Lake City, UT). Participants completed the first survey (T1) at the start of the academic year and completed baseline measures of their personality and community-oriented values. Approximately 6 months later, the COVID-19 pandemic became increasingly prominent in Canada, requiring classes to go online and an ethics amendment was submitted and approved by the institutional Internal Review Board for the addition of items related to the COVID-19 pandemic to this study. At T5, participant’s motivation for and the extent to which they adhered to social distancing measures was assessed. The retention rate from T1 to T5 was 81.3%. One-way ANOVAs revealed that participants who were lost to attrition tended to be less conscientious (F(1, 282) = 5.91, p = .02), however, no differences were found in their age, gender and their standing on the rest of the Big 5 traits.

All data are available on OSF (https://osf.io/km8e5/?view_only=b60b5e1e11c048b999b74db49b922db6). The present study was conducted in compliance with the [omitted for the review process] Research and Ethics boards and participants were financially compensated up to $50.00 in cash or a gift card for their time depending on the number of surveys they completed as part of this study.

Informant data and procedure

At baseline, participants were asked to voluntarily nominate and provide the E-mail of a friend and family member that could be contacted via E-mail to complete two brief 5–10 min surveys via Qualtrics experimental software (Qualtrics, Inc. Salt Lake City, UT). The informants completed one baseline survey at the start of the academic year, and a second 9 months later at the end of the study. At baseline, the informants perceptions of the participant’s personality was assessed. In the second survey, the informants were asked the extent to which they perceive the participant to be adhering to social distancing measures. 94.0% (268) of participants nominated a friend informant that could be contacted to complete an informant survey, and 94.7% (270) of participants nominated a family member informant. 75% of the nominated family members completed the baseline assessment and 55.2% completed the second end-of-study assessment. 75.9% of the nominated friends completed the baseline assessment and 54.8% completed the second end-of-study assessment.

Measures

Big 5 Personality traits. The participants’ standing on the Big 5 Traits (conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, and openness to experiences) was assessed at baseline using the 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava 1999). Participants responded to the prompt I am someone who… and rated each item based on how much they agreed that the items reflected their own personality on a scale from 1 (meaning strongly disagree) to 5 (meaning strongly agree). An example of an item used to assess conscientiousness is does things efficiently and an example of an item to assess extraversion is outgoing, sociable. Mean scores were calculated for each trait subscale and the reliability for all Big 5 traits were adequate (alphas > 0.74).

Informant perceptions of participants Big 5 traits. To assess the participant’s nominated friend and family member’s perceptions of the participant’s Big 5 traits, each friend and family member also completed the BFI with an adapted prompt that said [insert participant name] is someone who….

Adherence to social distancing. To assess the extent to which participants complied with public health recommendations to socially distance, participants rated and a mean was calculated from the following two items on a scale from 1 (meaning not at all) to 7 (meaning completely): How much are you currently following the recommendations to stay home as much as possible? and To what extent have you adopted the goal of social distancing?

Informant perceptions of social distancing adherence. To assess the extent to which informants perceive participants to have complied with social distancing guidelines, participants rated the following item on a scale from 1 (meaning not at all) to 7 (meaning completely): How much is [insert participant name] currently following the recommendations to stay home as much as possible?

Motivation for social distancing. To assess participant’s motivation for adhering to social distancing measures, they completed a 7-item adapted version of the motivation measure used in Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Nemiec (2009). The following items were used to assess participant’s autonomous motivation for social distancing (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75): The recommendations reflect my values, I find these recommendations meaningful, I understand why these recommendations are important. The following items assessed participant’s controlled motivation (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84): I would feel guilty if I did not follow the recommendations, I feel pressured to do so, I don’t want to get criticized for not following the recommendations, Others would disapprove of me. Participants rated each item on a scale from 1 (meaning not at all true of me) to 7 (meaning very true of me).

Community Aspirations. In order to assess participant’s intrinsic community aspirations, a subscale of the shortened 12-item version of Kasser & Ryan’s (1996) Aspiration Index was used. Note that this shortened version on the Aspiration Index has been used in past studies (e.g., Hope et al., 2016; 2019). On a scale from 1 (not all that important) to 7 (very important), participants responded to the following two items to assess their community aspiration: To work for the betterment of society and To assist people who need it, asking nothing in return.

Results

Primary analyses

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and correlations among the key variables used in this study. Importantly, in terms of building our later path analysis model that tested the mediational role of autonomous motivation and community values in the relation between traits and social distancing, agreeableness (r = .16, p = .02), and conscientiousness (r = .16, p = .01) were the only two Big 5 traits correlated with social distancing and were therefore the only two traits included in the model. In addition, autonomous motivation for social distancing was significantly positively correlated with social distancing (r = 58, p < .001), whereas controlled motivation was unrelated. Therefore, only autonomous motivation for social distancing was included in the subsequently tested model. Age was negatively related to social distancing (r=-.14, p = .03), whereas gender was unrelated. None of the Big 5 traits were correlated to participant’s age and gender, except being female was significantly positively related with neuroticism (r = .12, p = .04).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and correlations between all variables of interest. (Note. Bolded terms represent p < .05; Aut. Mot. = autonomous motivation; Com. = community; Con. Mot. = controlled Motivation; SD = social distancing; T1 = baseline assessment; T5 = fifth follow-up survey. The values along the diagonal are the Cronbach alphas for the various scales or correlations between items for constructs assessed with two items).)

| M | (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Extraversion | 3.15 | .91 | α = .88 | .11 | .09 | − .29 | .24 | .10 | .05 | − .11 | .03 |

| 2. Agreeableness | 3.78 | .64 | α = .74 | .18 | − .16 | .15 | .33 | .14 | .01 | .16 | |

| 3. Conscientious | 3.52 | .71 | α = .80 | − .18 | .01 | .23 | .22 | .06 | .16 | ||

| 4. Neuroticism | 3.29 | .89 | α = .87 | .01 | .12 | .03 | .20 | − .07 | |||

| 5. Openness to Experience | 3.62 | .68 | α = .78 | .32 | .06 | − .08 | .04 | ||||

| 6. T1 Com. Values | 5.75 | 1.16 | r = .50 | .31 | .09 | .30 | |||||

| 7. T5 Aut. Mot. For SD | 6.21 | 1.00 | α = .75 | .21 | .58 | ||||||

| 8. T5 Con. Mot. For SD | 4.59 | 1.69 | α = .84 | .06 | |||||||

| 9. T5 SD | 6.41 | .92 | r = .77 |

Main analyses

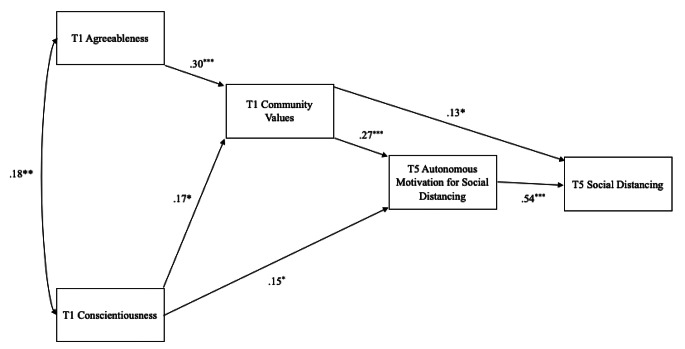

A path model analysis was performed using robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) procedures using MPlus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) to test the mediational role of autonomous motivation for social distancing and community values in the relation between traits (i.e. agreeableness and conscientiousness) and social distancing1. The syntax and output are available on OSF (https://osf.io/km8e5/?view_only=b60b5e1e11c048b999b74db49b922db6). The model fit the data adequately: MLR χ2 (df = 3, N = 284) = 1.365, p = .713, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA < 0.000 (< 0.000, 0.073), SRMR = 0.016. Please refer to Fig. 1; Table 2 for a full summary of the statistically tested paths and a display of the model. Importantly, a serial mediational path was found from agreeableness to T5 social distancing through both community values and autonomous motivation. The same serial mediational path was found from conscientiousness to T5 social distancing. Interestingly, a mediational path was also found from conscientiousness to T5 social distancing through autonomous motivation alone, however, this same path was not found for agreeableness.

Fig. 1.

Path model analyses of the mediational pathways from agreeableness and conscientiousness to adherence to social distancing guidelines through community values and autonomous motivation for social distancing. All significant paths and covariances are shown in the model; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Table 2.

Summary of paths explored in the path model analyses exploring the mediational role of autonomous motivation for social distancing and community values in the relation between traits (i.e. agreeableness and conscientiousness) and social distancing

| Path | B[95% CI], p |

|---|---|

| Direct Effect | |

| T1 Agree. ◊ T1 Com. Val. | 0.30[0.19, 0.41], p < .001 |

| T1 Consci. ◊ T1 Com. Val. | 0.17[0.06, 0.28], p = .003 |

| T1 Consci. ◊ T5 aut. mot. for SD | 0.15[0.02, 0.28], p = .02 |

| Com. Val.◊ T5 aut. mot. for SD | 0.27[0.13, 0.42], p < .001 |

| T5 aut mot. For SD ◊ T5 SD | 0.54[0.34, 0.69], p < .001 |

| T1 Com. Val.◊ T5 SD | 0.13[0.02, 0.26], p = .03 |

| Indirect Effect from Consci to T5 SD | |

| T1 Consci. ◊ T5 aut mot. For SD ◊ T5 SD | .08 [0.02, 0.17], p = .04 |

| T1 Consci. ◊ T1 Com. Val.◊ T5 SD | 0.02 [0.004, 0.06], p = .06 |

| T1 Consci. ◊ T1 Com. Val. ◊ T5 aut. mot. For SD .◊ T5 SD | 0.03 [0.01, 0.06], p = .046 |

| Indirect Effect from Agree to T5 SD | |

| T1 Agree. ◊ T1 Com. Val.◊ T5 SD | 0.04[0.01, 0.09], p = .04 |

| T1 Agree. ◊ T1 Com. Val. ◊ T5 aut. mot. For SD .◊ T5 SD | 0.04[0.02, 0.09], p = .012 |

Note. agree = agreeableness; aut. mot = autonomoour motivation; Consci = conscientiousness; Com. Val. = T1 community values; SD = social distacning; Bolded values indicate significance. STDYX values were reported

Replicating main results with informant ratings of big 5 traits and social distancing

Family reports at baseline of participants’ Big Five Traits were available for 201 individuals and peer reports were available for 200. Family reports of social distancing were available for 144 participants and peer reports were available for 143. The correlations among participant and informant perceptions of the participant’s social distancing, agreeableness and conscientiousness can be found in Table 3. Importantly, participant ratings of their own social distancing significantly correlated with friend (r = .39, p < .001) and family member (r = .33, p < .001) reports of participant social distancing. Both informants also agreed significantly regarding participant’s level of adherence to social distancing guidelines (r = .32, p = 002). Participants’ self-reported ratings of their agreeableness were significantly positively correlated with those of friend (r = .47, p < .001) and family member (r = .40, p < .001 ) reports of participant agreeableness. Participants self-reported ratings of their conscientiousness were significantly positively correlated with those of friend (r = .52, p < .001) and family member (r = .49, p < .001 ) reports of participant agreeableness. Family members and peers agreed significantly in their ratings of participants’ level of Conscientiousness (r = .52, p < .001) and Agreeableness (r = .34, p < .001).

Table 3.

Correlations among participant and informant perceptions of the participant’s social distancing, agreeableness and conscientiousness. (Note. Bolded terms represent p < .05; Agree = agreeableness; Consci = conscientiousness; SD = social distancing)

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Participant rated SD | .39 | .33 | .16 | .02 | .03 | .16 | .07 | < .00 |

| 2. Friend rated SD | .32 | − .07 | .20 | .12 | .15 | .17 | .16 | |

| 3. Family member rated SD | .14 | .17 | .27 | .04 | .20 | .11 | ||

| 4. Participant rated Agree | .47 | .40 | .18 | .10 | .13 | |||

| 5. Friend rated Agree | .34 | .08 | .30 | .13 | ||||

| 6. Family member rated Agree | − .04 | .17 | .34 | |||||

| 7. Participant rated Consci. | .52 | .49 | ||||||

| 8. Friend rated Consci. | .52 | |||||||

| 9. Family member rated Consci. |

We planned to use the informant reports to replicate the central findings of the current investigation – that the Big 5 traits of Conscientiousness and Agreeableness were significantly related to levels of adherence. Mean scores for the traits and social distancing were calculated across the family and peer reporters, resulting in T1 trait scores for 242 participants and T6 social distancing scores for 200 participants. Informant reports of participants’ social distancing (Mean = 6.54, SD = 0.87) were regressed on informant reports of participants’ traits of Conscientiousness (Mean = 4.03, SD = 0.65) and Agreeableness (Mean = 4.11, SD = 0.57). A significant multiple R of 0.311 was obtained, F (2, 197) = 10.56, p < .001. Informants’ ratings of Conscientiousness (beta = 0.199, t (197) = 2.85, p = .005, 95% CI [0.08, 0.45]) and Agreeableness, (beta = 0.257, t (197) = 3.53, p = .001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.63]) were significantly positively related to their ratings of participants level of adherence. The traits of extroversion, openness, and neuroticism were unrelated to reports of adherence (p’s > 0.20). The significant results for informant ratings suggest that the positive relation between the traits of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness with adherence to social distancing guidelines were not simply the product of self-report biases.

Discussion

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the need to adhere to government health regulations to limit the spread of the virus has been of the utmost importance. The present study used a prospective longitudinal design to investigate personality and motivational factors that predict the extent to which an individual adheres to social distancing measures in a sample of undergraduate students during the first wave of the pandemic. First, we aimed to integrate self-determination theory’s concept of autonomous and controlled motivation to explore whether individuals who managed to more effectively internalize and integrate the importance and value of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic and felt more autonomous in this endeavor would be more likely to adhere to the social distancing guidelines. Our results supported this hypothesis, which is consistent with several decades of research that have consistently found more effective goal-directed behaviour as a result of more autonomous engagement (e.g., Koestner 2008; Koestner et al., 2008; Milyavskaya et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2021). Interestingly, controlled motivation was not associated with social distancing, although we do wonder if this changed as time progressed throughout the second and third waves of the pandemic. The implication of these motivational findings is that, in terms of informing future interventions aimed at increasing social distancing, using more autonomy supportive strategies, such as perspective-taking and providing elements of choice, which would foster more autonomous “want to” motivation, would be more effective than controlling strategies, such as highlighting threats and fines.

In addition, we had hypothesized that Big 5 personality traits that promote collaboration, such as conscientiousness and agreeableness, would orient individuals towards more intrinsic community values and would predispose an individual to better internalize the COVID-19 health recommendations. The results supported this hypothesis in that individuals who were higher on agreeableness and conscientiousness tended to engage in more social distancing. The mediation analyses suggest that the link between the personality characteristics and adhering to the guidelines may result from greater internalization and integration of the importance and value of the social distancing guidelines and as a function of greater concern for the welfare of the community. The indirect path from conscientiousness to social distancing through autonomous motivation for social distancing was confirmed, whereas we did not find the same path for agreeableness. Being rule-bound and mindful of guidelines, social distancing may have felt easier and more natural to those higher in conscientiousness, resulting in greater autonomous motives to socially distance. In contrast, the link from agreeableness to social distancing seemed to primarily work through orienting individuals towards their community values, which in turn promoted socially cooperative behaviour. These results suggest a need to further study and promote socialization techniques (e.g., parenting, schooling, coaching) that increase agreeableness and conscientiousness in order to increase people’s willingness to adhere to important health guidelines during world crises where there is a need to work collaboratively together to protect the public at large. In other words, we suggest that it may be possible to utilize techniques to increase one’s standing on traits and values that orient people towards being more cooperative and collaborative, which could translate into greater adherence to public health guidelines during world crises. There is emerging evidence that personality is more flexible than previously thought, making these suggestions even more plausible (McAdams, 2015; Moore et al., 2020).

Within the present study, we also aimed to replicate our longitudinal findings linking traits to social distancing using friend and family informant reports of participants’ personality and social distancing to incorporate a more objective assessment of participants’ personality and social distancing behaviours. Once again, we found that informant ratings of participants’ agreeableness and conscientiousness were positively associated with informant ratings of the participant’s adherence to social distancing guidelines. This replication of our results linking traits to social distancing behaviours bolsters our confidence in these findings.

The present study had several methodological strengths, such as having recruited a large sample and using a prospective longitidunal design that allowed us to use individual differences assessed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic to investigate variations in behavioral responses. In addition, we replicated our findings using informant reports which enhanced our confidence in these findings. There were also a few limitations to the present investigation that are important to note. In terms of the quality of measures used in the present study, future research would benefit from using more comprehensive measures of community values and participant and informant reports of social distancing. Additionally, although we did incorporate informant reports of personality and social distancing, future research would benefit from using behavioural measures of social distancing, such as phone tracking methods. Moreover, we acknowledge that the retention rate of informant reports and the coefficients in our main path analysis were lower than optimal. Additionally, the correlations between informant and self-reported assessments of personality were lower than expected. Furthermore, the study sample was drawn narrowly from undergraduate students attending a large public North American university and the sample was disproportionately female. Therefore, future research would benefit from exploring whether these findings are replicable in a more representative sample. Moreover, it’s important to note that our analyses were correlational, and we can therefore not make firm conclusions about the causation.

At the time of writing this article, Canada has experienced three waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first wave, COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were strictly imposed so that social gatherings were prohibited and all non-essential businesses (e.g., restaurants, gyms, services such as hairdressing salons) were ordered to close until the spring of 2020. During this lockdown period, there was variation in how much individuals complied with the restrictions, however, due to the closures there was not much else to do other than stay home. Throughout the pandemic, there have been periods where some of the restrictions were lifted (e.g., non-essential businesses opened, social gatherings within limits were allowed), but there still was the need for people to remain vigilant to limit further spread of the virus. An interesting future direction for this line of research would be to explore how personality and motivational variables impacted people’s motivation for and actual adherence to social distancing guidelines throughout these different periods.

Moreover, the implications and real-world applicability of this research merit further consideration. The present study aimed to shed light on personality and motivational variables that are predictive of adhering to public health guidelines within the context of the pandemic with the hope of informing future interventions aimed at encouraging adherence during the remainder of the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Indeed, future research could explore whether these findings generalize across different kinds of public health guidelines, such as those aimed at increasing health promoting behaviours and cooperation during future crises and natural disasters. Our results suggest that to increase adherence to public health guidelines, it would be important for interventions to appeal to aspects of our personality that promote collaboration and cooperation and utilize strategies that promote more autonomous, rather than controlled, motivation for goal-directed behaviour.

Conclusions

To slow the spread of the virus during the COVID-19, many of us we were required make sacrifices and significantly change the way we live our lives. Naturally, this can be quite challenging and there was significant variation in the extent to which various individuals and groups adhered to the social distancing recommendations. The present study integrated personality theories and self-determination theory’s concepts of autonomous motivation and intrinsic community values to shed light on personality and motivation factors that are predictive of greater social distancing. We are hopeful that a better understanding of personality and motivational factors that are associated with greater internalization and adherence to public health guidelines can pave the way for better targeted interventions in similar or related world crises.

Footnote

1During data analysis, two alternate models were tested based on different theoretical ideas of how the data might work. The final model presented was chosen based on having the best model fit indices. The following fit indices were given priority in model evaluation: the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). According to Kline (2011) and Tabachnick & Fidell (2007), the CFI should be 0.95 or higher, while the RMSEA and SRMR should be 0.06 or lower for acceptable model fit. The first alternate model was identical to the final model, except there was no direct association from conscientiousness to community values. We had tested this model as we had wondered if agreeableness and conscientious might have different mechanisms linking these them to social distancing; however, this model did not have adequate fit (MLR χ2 (df = 4, N = 284) = 11.08, p = .03, CFI = .96, RMSEA .08 (.03, .14), SRMR = .05). The second alternate model was identical to the alternate model just described, except there was no direct association from community values to social distancing. We had tested this model as we had wondered if community values may only be associated with social distancing through autonomous motivation for social distancing; however, this model did not have adequate fit ((MLR χ2 (df = 5, N = 284) = 16.96, p = .005, CFI = .93, RMSEA .09 (.05, .14), SRMR = .06).”

Acknowledgements

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a fellowship from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) to Amanda Moore. In addition, this research and data collection was supported by a grant to Richard Koestner from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the Le Fonds de Recherche du Québec Société et Culture (FQRSC).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amanda Marie Moore, Email: amanda.moore@mail.mcgill.ca.

Anne Catherine Holding, Email: anne.holding@mail.mcgill.ca

Shelby Levine, Email: Shelby.levine@mail.mcgill.ca.

Theodore Powers, Email: tpowers@umassd.edu

Richard Koestner, Email: richard.koestner@mcgill.ca

References

- Ai, P., Liu, Y., & Zhao, X. (2019). Big Five personality traits predict daily spatial behavior: Evidence from smartphone data. Personality and Individual Differences, 147(October 2018), 285–291. 10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.02

- Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and Health-Related Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis of the Leading Behavioral Contributors to Mortality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):887–919. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Eisenberg N. Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In: Hogan R, Johnson JA, Briggs S, editors. Handbook of personality psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 795–824. [Google Scholar]

- Hope Nora H., Milyavskaya Marina, Holding Anne C., Koestner Richard. The humble path to progress: Goal-specific aspirational content predicts goal progress and goal vitality. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;90:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hope, Nora H, Holding, Anne C, Verner-Filion, Jeremie, Sheldon, Kennon M & Koestner, Richard. (2019). The path from intrinsic aspirations to subjective well-being is mediated by changes in basic psychological need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: A large prospective test. Motivation and Emotion, 43, 232-241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9733-z

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research, 2, 102–138

- Kasser T, Ryan RM. Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:280–287. doi: 10.1177/0146167296223006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koestner R. Reaching one’s personal goals: A motivational analysis focusing on autonomy. Canadian Psychologist. 2008;49:60–67. doi: 10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koestner R, Otis N, Powers T, Pelletier L, Gagnon H. Autonomous motivation, controlled motivation and goal progress. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:1201–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestner Richard, Otis Nancy, Powers Theodore A., Pelletier Luc, Gagnon Hugo. Autonomous Motivation, Controlled Motivation, and Goal Progress. Journal of Personality. 2008;76(5):1201–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S. L., Holding, A. C., Milyavskaya, M., Powers, T. A., & Koestner, R. (2020). Collaborative autonomy: The dynamic relations between personal goal autonomy and perceived autonomy support in emerging adulthood results in positive affect and goal progress. Motivation Science

- Levine, S. L., Milyavskaya, M., Powers, T. A., Holding, A. C., & Koestner, R. (2021). Autonomous motivation and support flourishes for individuals higher in collaborative personality factors: Agreeableness, assisted autonomy striving, and secure attachment.Journal of Personality [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li-Grining CP. Effortful Control among low-income preschoolers in three cities: Stability, change, an individual differences. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:208221. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. The art and science of personality development. Guilford Publications. 2015 doi: 10.5860/choice.192399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matrajt L, Leung T. Evaluating the effectiveness of social distancing interventions to dela or flatten the epidemic curve of coronavirus disease. Emerging infections disease. 2020;26:1740–1748. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Validation of the Five-Factor Model of Personality Across Instruments and Observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987 doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milyavskaya M, Inzlicht M, Hope N, Koestner R. Saying “no” to temptation: Want-to motivation improves self-regulation by reducing temptation rather than by increasing self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pspp0000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AM, Holding A, Buchardt L, Koester R. On the efficacy of volitional personality change in young adulthood: Convergent evidence using a longitudinal personal goal paradigm. Motivation and Emotion. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11031-021-09865-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Holding A, Verner-Filion J, Harvey B, Koestner R. A longitudinal investigation of trait-goal concordance on goal progress: The mediating role of autonomous goal motivation. Journal of Personality. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jopy.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). MPlus. The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers: User’s guide (5th ed.)

- Noftle EE, Shaver AJ. Attachment dimensions of the Big Five personality traits: Associations and comparative ability to predict relationship quality. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:179–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2004.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, Shook N. Adolescents’ Motivations to Engage in Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations With Mental and Social Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR. Effortful control. In: Zentner M, Shiner RL, editors. Handbook of temperament. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory:Basic psychological needs in

- motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications

- Ryan RM, Sheldon KM, Kasser T, Deci EL. All goals are not created equal: The relation of goal content and regulatory styles to mental health. In: Bargh JA, Gollwitzer PM, editors. The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM. Becoming Oneself: The Central Role of Self-Concordant Goal Selection. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2014;18:349–365. doi: 10.1177/1088868314538549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Niemiec C. Should parental prohibition of adolescents’ peer relationships be prohibited? Personal Relationships. 2009;16:507–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01237.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swickert R, Abushanab B, Bise H, Szer R. Conscientiousness Moderates the Influence of a Help-Eliciting Prime on Prosocial Behavior. Psychology. 2014;05(17):1954–1961. doi: 10.4236/psych.2014.517198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5. New York: Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zajenkowski M, Jonason PK, Leniarska M, Kozakiewicz Z. Who complies with the restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19?: Personality and perceptions of the COVID-19 situation. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;166(June):110199. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]