Summary

Drowning has been a neglected health issue, largely absent from the global health and development discourse, until the UN General Assembly adopted its first resolution on global drowning prevention in 2021. This policy analysis examines the role of issue characteristics, actor power, ideas, and political contexts in the emergence of drowning prevention, and it also identifies opportunities for future actions. We identified three factors crucial to enhancing prioritisation: (1) methodological advancements in population-representative data and evidence for effective interventions; (2) reframing drowning prevention in health and sustainable development terms with an elevated focus on high burdens in low-income and middle-income contexts; and (3) political advocacy by a small coalition. Ensuring that the UN resolution on global drowning prevention is a catalyst for action requires positioning of drowning prevention within global health and sustainable development agendas; strengthening of capacity for multisectoral action; expansion of research measuring burden and identifying solutions in diverse contexts; and incorporation of inclusive global governance, commitments, and mechanisms that hold stakeholders to account.

Introduction

Drowning is estimated to claim more than 236 000 lives annually, with 90% of these deaths in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). It is among the top ten leading causes of death for people aged 1–24 years, in every region of the world.1

Despite this burden, drowning has been largely absent from the global health and development discourse and practice.2 This absence changed with the first UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution on global drowning prevention adopted in April, 2021 (hereafter referred to as the UN resolution).3 This UN resolution called for an urgent and coordinated response, with effective, scalable, low-cost interventions. Although non-binding on UN member states, the UN resolution is the first high-level commitment to drowning prevention and, as such, warrants further investigation.

We examined factors that shaped the prioritisation of drowning prevention in the two decades leading to the UN resolution and identified opportunities to inform future actions for drowning prevention.

Methods

In-depth interviews and document review

In summary, we used a process-tracing methodology,4 and triangulated data collected through in-depth interviews and document analysis of peer-reviewed, grey literature and documents cited in the UN resolution. The search strategy and selection criteria are detailed in the appendix (p 2).

In-depth interviews were conducted using a web-conferencing platform between April and July, 2021. We applied a purposive-snowball informant selection strategy. First, identifying key informants with first-hand knowledge of the global prioritisation process and actors familiar with the UN resolution negotiation process. Additional informants were identified through literature review, press statements, and by referral from other informants until the study reached thematic saturation.

The interviews were recorded and lasted about an hour. The interview guide and analysis were underpinned by Shiffman and Smith's framework,5 which focuses on four categories that shape such prioritisation: issue characteristics, actor power, ideas, and political context. The guide was adjusted for participant involvement in specific areas of the prioritisation process.

Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis for factors shaping political priority for drowning prevention. The interviews were transcribed using caption feature, coded, and assessed to identify relevant quotes. A framework analysis approach was adopted, entailing deductive thematic analysis of findings drawn from the Shiffman and Smith framework.5 J-PS and JJ iteratively reviewed the interview data against each element of the framework, independently coded the data, and synthesised the findings after discussion. To minimise bias we triangulated data sources, corroborating information from interviews with documentary sources. We synthesised informant feedback, sharing our interim analysis with 13 participants, of whom five provided input into themes and timelines.

Positionality and reflexivity

Our multidisciplinary research team included both insiders and outsiders. J-PS, JJ, and DRM are insiders as they are directly involved in areas of the drowning prevention field. J-PS is a doctoral fellow and conducted all interviews. J-PS and DRM are drowning-prevention advocates and contributors to the prioritisation process. JJ is an LMIC injury-prevention researcher with insights into the prioritisation process. KB and RN are outsiders with expertise in policy analysis, agenda setting, and public health.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel D: Biomedical at The University of New South Wales (reference: HC200929).

Results

We identified 39 documents, of which 29 referred to drowning across the fields of: child and adolescent health; lifesaving; disaster risk reduction; water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH); sustainable cities; alcohol harm reduction; and humanitarian affairs. No relevant peer-reviewed studies on global prioritisation of drowning prevention were identified.

We interviewed 16 informants from six constituencies: UN agency, international non-governmental organisation (NGO), national NGO, philanthropic group, academic, and national government (including development agency; appendix pp 3–4). These informants represented international groups (four [25%] of 16 participants), high-income countries (HICs; nine [56%]), and LMICs (three [19%]; appendix pp 3–4).

Timeline

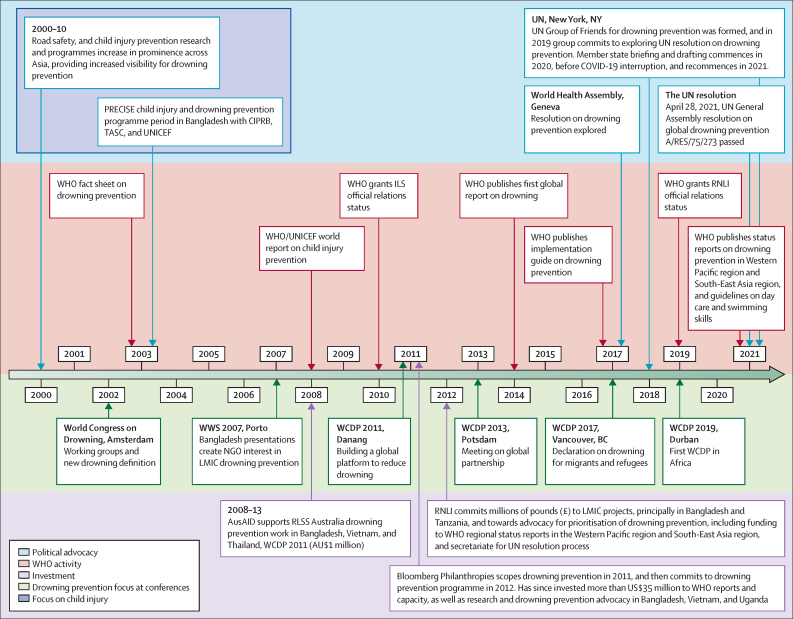

We constructed a timeline showing the inter-relationships of actors, milestones, and factors that contributed to the prioritisation of drowning prevention in 2000–21 (figure).

Figure.

Selected major milestones relating to the prioritisation of drowning prevention (2000–21)

AusAID=Australian Government Agency for International Development. CIPRB=Centre for Injury Prevention and Research Bangladesh. ILS=International Life Saving Federation. LMIC=low-income and middle-income country. NGO=non-governmental organisation. PRECISE=Prevention of Child Injuries through Social-Intervention and Education (Bangladesh). RLSS=Royal Life Saving Society. RNLI=Royal National Lifeboat Institution. TASC=The Alliance for Safe Children. WCDP=World Conference on Drowning Prevention. WWS=World Water Safety Conference.

Issue characteristics

The issue characteristic domain reviews the presence or absence of credible indicators, relative issue severity, and the extent to which effective evidence-informed interventions are available.5 The issue characteristics reinforced in the UN resolution are summarised in panel 1.

Panel 1. Relevant issue characteristics and solutions cited in UN resolution on global drowning prevention A/RES/75/273.

Preamble outlining issue characteristics

-

•

Over 2·5 million preventable deaths in the past decade

-

•

Drowning is largely unrecognised relative to its impact

-

•

Over 90% of drowning deaths occur in low-income and middle-income countries

-

•

Africa has the highest drowning rates, and Asia carries the highest burden

-

•

Drowning takes place in rivers, lakes, domestic water storage, swimming pools, and coastal waters

-

•

Drowning disproportionately affects children and adolescents in rural areas and presents as a social inequity issue

-

•

The burden is under-represented due to exclusion of flood and transport incidents

-

•

Drowning prevention could be a Sustainable Development Goal measure for child deaths, and could be framed as protecting investments in child development

-

•

Preventable and scalable, low-cost interventions exist

Voluntary member state actions outlining solutions

-

•

Appoint a national focal point for drowning prevention

-

•

Develop a national drowning prevention plan

-

•

Develop drowning prevention programming in line with WHO recommended interventions

-

•

Ensure the enactment and active enforcement of water safety laws across all relevant sectors

-

•

Include drowning within civil registration and vital statistics registers

-

•

Promote drowning prevention public awareness and behaviour change campaigns

-

•

Encourage the integration of drowning prevention within existing disaster risk reduction programmes

-

•

Support international cooperation by sharing lessons learned

-

•

Promote research and development of innovative drowning prevention tools and technology

-

•

Consider the introduction of water safety, swimming, and first-aid lessons as part of school curricula

Overcoming gaps in reporting of drowning data through methodological advances

Early challenges for prioritisation included that drowning commonly results in immediate death and is, therefore, often omitted from civil and vital registration systems in LMICs as the child rarely survives the journey to hospital or emergency medical services. Gaps in the reporting of fatal and non-fatal drowning, disagreement on the underlying codes, and the exclusion of drowning caused by floods or transport incidents from official estimates, all contribute to the under-representation of the drowning burden.

Participants identified the advent of population-based representative mortality data as key to the emergence of drowning as a major issue. From 1998 to 2005, studies investigating child mortality or injury, using population surveys, identified previously unreported high rates of drowning among children aged 1–5 years, which contributed to increasing visibility of the problem.6, 7, 8

“We did door to door surveys in six different countries in Asia to see what was killing our children. And it was a shock, aside from road traffic, the biggest killer by far was drowning.” Interview 13, philanthropic group.

Verbal autopsy methods contributed to strengthened global estimates and have subsequently been applied to intervention planning.9, 10 Verbal autopsy, when applied to drowning, has high sensitivity and specificity and overcomes the disincentives (eg, government and other medical charges) to reporting drowning to authorities at the community level.

Shifts in child disease burden

High rates of drowning in children assisted in raising attention to the issue. The epidemiological shift in disease burden enhanced the visibility of drowning, with a high proportion of deaths attributable to drowning increasingly evident in children aged 1–5 years.

“The International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh in Matlab had this wonderful chart. You had the amount of child deaths, largely caused by diarrhoea and vaccine preventable diseases. When that mountain came down [a result of the child survival agenda]—surprise—it was another mountain behind, and that mortality was drowning and other injuries.” Interview 15, UN agency.

Emergence of effective solutions

Participants described the development of effective child drowning interventions in LMICs as crucial to the prioritisation process. In the mid-2000s, a programme in Bangladesh initiated solutions such as day care and teaching of swimming skills.11 The inclusion of these and other interventions in WHO reports in 2014 and 20172, 12 strengthened acceptance and led to further large-scale studies in Bangladesh and Vietnam. WHO then published guidance for day care and swimming skills in 2021.13

Actor power

Actor power relates to the strength and cohesion of individuals and groups, and the effectiveness of guiding institutions and mobilisation of civil society, all thought to be key to prioritisation processes.5

Guiding institutional engagement of WHO and UNICEF in drowning prevention

The role of WHO and UNICEF was considered essential, with child injury prevention thought to have provided a stepping stone for both into drowning prevention. WHO was described as bringing credibility to drowning prevention, using institutional power to reinforce the need for evidence, raising its standing in health discourse, and strengthening actor cohesion through conference co-sponsorship, meetings, and publications.

On WHO's impact: “the public health approach, framing drowning as a large problem, describing the magnitude of drowning in relation to other health issues, and by the way we look at evidence guided interventions”. Interview 1, UN agency.

UNICEF helped initiate programmes in Bangladesh, Thailand, and Vietnam between 2002 and 2014 that were viewed as generating awareness and evidence. Governments in each of these three countries continue to support national policies and programmes. A policy analysis found that the Government of Bangladesh had taken the lead in designing a national drowning prevention policy.14 Both UNICEF and WHO were involved in planning for the UN resolution and member state briefings.

Use of professional positionality to promote drowning prevention

Individuals applied their positional and network power, including the US ambassador to Vietnam (1997–2001), who identified drowning as a major issue while scoping health projects to strengthen Vietnam–US relations, and then formed The Alliance for Safe Children. The UNICEF country representative for Vietnam and later Bangladesh was central to early efforts, commissioning injury surveys that identified drowning burdens in both countries before 2003. The UN permanent representatives for Bangladesh and Ireland, who jointly proposed the UN resolution, were also highlighted as powerful contributors to policy prioritisation.

Role of philanthropic groups in countering a lack of government investment

Philanthropic groups helped to overcome resourcing gaps through initiatives targeting political buy-in, employing advocacy specialists, and seeding government programmes. Since 2011, Bloomberg Philanthropies has made substantial investments in WHO,2, 12 and more recently, has increased investments in government advocacy in Bangladesh, Uganda, and Vietnam. The UK and Ireland charity and NGO Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) has invested substantial funds into WHO regional status reports for drowning, global advocacy, UN engagement, and various LMIC projects since 2012.15, 16

“But if you think about advocacy, it is so important across all issues, but there aren't advocates that have the expertise in [drowning prevention].” Interview 4, philanthropic group.

Official development assistance involvement in drowning prevention was limited to a few funded initiatives, principally in Asia. In key examples, national NGO involvement was crucial to official development assistance investment. The former Australian Agency for International Development gave support (particularly regarding domestic policy alignment) to the Royal Life Saving Society–Australia initiatives (2008–13) in Bangladesh, Thailand, and Vietnam, and the World Conference on Drowning Prevention 2011.

“[Australian Government] support based on concerning data, promising solutions, and the involvement of Australian NGO expertise in an issue that linked closely to domestic audiences.” Interview 11, development agency.

Mobilisation of lifesaving NGOs

Lifesaving NGOs, including International Life Saving Federation members, were important in the prioritisation process. These NGOs organise themselves around technical, professional, and volunteer networks centred on rescue, resuscitation, water safety, and swimming education. They often play a key role in national drowning prevention agendas. In some cases, HIC NGOs invested in LMIC research, capacity building, and national and global advocacy.

“People self-select to those [lifesaving NGO] groups, they can be almost fanatical. They…are totally persuaded about what they are doing and why they are doing it. So, they can drive the agenda.” Interview 5, academic.

The lifesaving NGOs were viewed by some academics as lacking expert power and having strong ideological ties to rescue rather than prevention. Both criticisms were seen as barriers to earlier prioritisation.

“[An academic] said to me that the reason drowning is not going to become a public health thing, and we're not going to get WHO or donors engaged, is because there's no unifying vision and you don't have enough academic players.” Interview 2, international NGO.

Growth of academic networks and child injury prevention agendas

Throughout the 2000s, academic interest in drowning prevention increased alongside growth in road safety and child injury prevention agendas. Early studies across Asia,8, 17 and the World Report on Child Injury Prevention in 2008,18 served as catalysts for increased drowning prevention research.19

“Clearly, [drowning] was not the most appealing issue, because the most appealing issue was road traffic, because it was so apparent to all the decision makers, because they saw it outside on the street.” Interview 15, UN agency.

Interest among injury researchers provided further impetus for the adoption of public health approaches and narratives. Tensions around leadership and methodological rigour had some effect on cohesion and consensus among actors.

Ideas

The ideas domain contends that internal consensus on the problem definition and solutions contributes to successful generation of political traction. The way an issue is portrayed to external audiences, particularly political actors, has equal importance.5

Lifesaving, water safety, or drowning prevention?

Historically, lifesaving NGOs portrayed efforts to prevent drowning as water safety. Actors involved in policy making found that framing problematic, as in LMICs water safety is most often associated with WASH agendas. The increased use of drowning prevention as an umbrella term throughout 2011–21 was influenced by public health actors, and its use contributed to issue prioritisation. A hypothesis published in 2019 suggested that there are co-benefits for drowning prevention and WASH when their aims are aligned.20

A neglected public health issue

The external positioning of drowning prevention as an overlooked issue is evident in early discourse. WHO statements in 2014 and 2017 reinforced the idea that drowning was neglected and under-resourced relative to other health issues.2, 12 These portrayals helped to cement drowning as an important health issue, and gain traction with donors and some member states.

The contribution of drowning prevention to sustainable development, disaster risk reduction, and climate change

The framing of drowning prevention in member states’ briefings reinforced the historical nature of a UN resolution and the inequities of drowning burdens, and drew comparisons with other well established development priorities. Crucially, drowning prevention was positioned as an enabler of progress towards climate resilience and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Proponents avoided positioning drowning in refugee and migration policy terms due to political complexities and a lack of agreement on solutions.

“There are essentially two pathways for technical official, they're dealing with either sustainable development matters and climate change, or health, and we were like, well, it covers both. Depending on which mission, they might have said this is more of a health lens for us, or sustainable development.” Interview 3, national NGO.

Political contexts

The political context domain focuses on policy windows and political moments that align to create opportunities, and on global governance structures that provide a platform for collective action.5

A small coalition in the absence of agreed globalgovernance

Governance played a small role in the political context for drowning prevention. Participants observed that a lack of global governance impeded efforts to set a cohesive agenda. Instead, decision making was attributed to a small, loose coalition that maintained a shared aspiration for global prioritisation. This group adopted informal consensus making and project-based agreements that accommodated overlapping interests and the resourcing of political prioritisation activities.

“I don't think we could really use the word governance. I think it's a collection of well-meaning advocates, and we have become friends and we became collaborators, and we are providing some leadership to this.” Interview 2, international NGO.

Advocacy at the World Health Assembly

The World Health Assembly and UNGA processes were the only examples cited by the informants of high-level political discourse. RNLI's recruitment of advocacy specialists with UN and international development experience was crucial to advancing political attention. Initial efforts to create a World Health Assembly resolution (May–November, 2017) were unsuccessful due in part to changes following the appointment of a new WHO director-general in 2017.

Success at the UNGA

Four factors were identified as essential to securing the UN resolution. First, a UN Group of Friends for Drowning Prevention was formed in 2018 and committed to the resolution process in 2019. Second, a small team consisting of the RNLI, WHO, and UNICEF provided technical expertise. Third, the RNLI resourced an independent secretariate to conduct member state briefings and draft the resolution. Finally, the positioning of drowning prevention as important to progress in sustainable development, climate change, and disaster agendas expanded the platform and secured co-sponsorship by 79 member states.

“Bangladesh symbolises the transition from HIC recreational focus [tertiary prevention] to public health approaches and drowning risk in activities of daily living focus. It is the country that first demonstrated that the biggest priority is the kids under the age of five.” Interview 2, international NGO.

The UN ambassadors from Bangladesh and Ireland were instrumental in building member state support. It was suggested that Bangladesh took on a leadership role because it was perceived as being at the front line in the fight against drowning, having a high drowning burden, and being central to the emergence of solutions. Ireland's drowning burden is largely related to recreational and maritime activities. It was suggested that Ireland's participation was in part driven by their interest in climate resilience and was complimentary to efforts to secure a temporary seat at the UN Security Council.

Challenges and opportunities to retaining political salience

Participants were asked to identify challenges and opportunities crucial to sustaining political prioritisation after the UN resolution. These challenges and opportunities are clustered into three themes.

Scaling up, transferability, and knowledge gaps for multisectoral action

Participants identified two challenges relating to context. First was the challenge of advancing drowning prevention in diverse political contexts across Asia, particularly in high-risk rural communities. Second was addressing knowledge gaps for issue characteristics and solutions across Africa, central America, and Small Island Developing States while countering the perceived over-reliance on solutions emanating from HIC and southeast Asian settings.

“Because there was lots of data from HICs and from countries like Bangladesh, where most people that drown are kids. If they are not kids drowning is [happening during] recreational [activities], [for example when] they are boating for leisure. No in Uganda they are not kids, and they are not boating for leisure. It's a very different angle, and I think globally that needs to be acknowledged.” Interview 5, academic.

Creating collaborations with actors within sustainable development, disaster, and climate resilience fields was viewed as a priority. Further research into drowning prevention within these contexts is needed to identify effective approaches.

“I think it [drowning prevention] still cuts across too many areas that will cause challenges, but also opportunities, because the lack of donors and the low evidence levels will be a potential barrier to certain areas.” Interview 10, national NGO.

Participants emphasised that forming multisectoral, multistakeholder coalitions might be essential to gaining further political attention. Some described emerging national responses that are led by non-health ministries as indicative of future approaches.

Sustaining high-level engagement

Participants identified sustained positioning with UN actors as a challenge. They also cited the need for timebound, measurable targets, and strengthened accountability mechanisms, to convert voluntary commitments into member state action. Advocating drowning prevention into existing UN agency work plans and reporting necessitates a coordinated and well resourced approach.

“The political clout and organisational climate [is needed] because if drowning [prevention] is going to make it, it needs the bigger UN agencies, the child focused NGOs, the potential overlaps with WASH and humanitarian agendas.” Interview 14, national NGO.

Strengthening actor cohesion, strategy, accountability, and partnership

Establishing or strengthening institutions to facilitate collective action is crucial to sustaining political prioritisation.21 Participants acknowledged the importance of WHO leadership, although some identified that resource gaps and competing priorities sometimes hindered WHO country office involvement in national efforts.

Some participants referenced a proposed global partnership as an opportunity to strengthen governance and strategic action.2 A coordinated, accountable, equitable, and inclusive partnership might facilitate sustained focus on global and country-level action.

On future success: “A global drowning prevention partnership that has a bit of funding and has shown itself to be effective in drawing together the full potential of the academic institutions, the NGO funders, the NGO organisations, and the philanthropic funders to get some key priority domains.” Interview 1, UN agency.

Discussion

The global prioritisation of drowning prevention was enabled by robust community-based mortality data, recognition of drowning as a public health challenge, and development of effective interventions, and then reinforced by WHO exercising institutional leadership.2, 12 Other factors included civil society mobilisation (lifesaving NGOs) around a shared commitment to preventing drowning in LMICs, and investments in research and government-focused advocacy by philanthropic groups. A semi-formal coalition coalesced around the prioritisation of drowning prevention in LMICs and set sights on securing high-level recognition. Member state engagement, led by the UN Group of Friends for Drowning Prevention, supported by the RNLI, WHO, and UNICEF, resulted in the first UNGA resolution on global drowning prevention in 2021.

Converting the UN resolution into action might rest on each proponent's ability to address strategic priorities for sustaining political prioritisation for drowning prevention (panel 2). These priorities are aligned to Shiffman's four challenges for global health networks,21 and aim to spark discussion among actors, both internal and external to the drowning prevention field.

Panel 2. Strategic priorities for sustaining political prioritisation for drowning prevention.

Problem definition: building consensus on the problem and solutions

Expand research measuring burden and identifying solutions across contextual diversity

-

•

Leverage the UN resolution on global drowning prevention as an urgent call for: improved data on burdens and contexts including occupational, adolescent, disaster risk reduction, and climate impacts; expanded across the regions, countries, and communities most susceptible to drowning; and focused on solutions in partnership with other sectors

Implementation research of known effective solutions

-

•

Translate known effective solutions to population programmes and policies on the basis of learnings from implementation research, with realist evaluations, identifying community priorities, challenges of insufficient resources, lack of technical capacity, and poor coordination among stakeholders and implementers

Positioning: portraying the issue to inspire actions by additional stakeholders

Ensure successful positioning with global health and sustainable development agendas

-

•

Map intersections and increase advocacy for drowning prevention within universal health coverage, Sustainable Development Goals, UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, and climate resilience agendas, and identify synergies and co-benefits

Consolidate action in Asia-Pacific and extend reach into all regions

-

•

Expand drowning prevention focus and reach across all regions, specifically Africa, South and central America, and Small Island Developing Nations to raise systemic awareness, stimulate governmental action, and improve contextual knowledge

Strengthen global commitments

-

•

Convert the UN resolution into sustained and accelerated engagement at UN and member state level by expanding the role of the UN Group of Friends; transform the voluntary actions into a framework for celebrating and sharing national successes; and expand commemorations for the World Drowning Prevention Day

Coalition building: expanding allies in sectors not yet engaged in drowning prevention

Extend partnerships with sectors currently considered external to the drowning prevention field

-

•

Prioritise pathfinding initiatives across research, advocacy, and programmes to realise the positive impact of partnering with other sectors including early childhood development; water, sanitation, and hygiene; disaster risk reduction; agriculture; and maritime

Strengthen capacity for multisectoral action

-

•

Harness the collective power of sectors and stakeholders in whole-of-society approaches that align and activate ministries, NGOs, academia, and the private sector to national and community drowning prevention plans and actions

Governance: establishing institutions to facilitate collective action

Build inclusive global governance with strengthened accountability

-

•

Establish a multisectoral, multistakeholder global partnership that unifies actors and strengthens cohesion and alignment to a common agenda, with the most susceptible and affected communities actively engaged in decision making

-

•

Develop a global strategy and explore approaches to increasing funding availability for advocacy, research, policy, and implementation of drowning prevention measures specifically in low-income and middle-income countries

NGO=non-governmental organisation.

First, the UN resolution must serve as an urgent call to strengthen consensus on the problem and solutions through improved data, contextual understandings, evidence for interventions, and the prioritisation of research across the regions, countries, and communities most susceptible to drowning. Strengthening civil and vital registration systems to report drowning in population-representative data might contribute to evidence-informed policy. Consensus building and multisectoral approaches might be challenged by the diverse nature of the drowning problem. Drowning of refugees and migrants in transit, although avoided in the resolution process, requires agreement on solutions and positioning within future advocacy.

Second, positioning drowning prevention to inspire action within global health and sustainable development agendas is essential. Addressing upstream social, economic, and environmental determinants within these agendas should provide opportunities. For example, infrastructure that mitigates risks associated with river crossings or policies that enhance child rights and access to school education might in turn reduce exposures to water hazards.

Third, national and community level coalitions need to be formed to harness the collective power of actors from relevant sectors and to tailor solutions to localised contexts. Global, regional, and national status reports for drowning prevention could raise awareness and serve as a catalyst for whole-of-government and multisectoral approaches.15, 16

Whole-of-government and all-of-societies approaches might need non-governmental and private sector engagement to strengthen capacity for multisectoral action.22 Mobilising civil society, including practitioner communities for lifeguards, and swimming and youth advocates, could pressure policy makers to initiate and sustain efforts.

Finally, governance and commitments with matching accountability systems are needed to mobilise knowledge, expertise, and financial resources. A global partnership might help to unify actors around a strategy, and increase engagement with diverse constituencies including UN agencies, governments, donors, civil society, and academics. Such partnerships are core to the SDG agenda.23 Future models might be guided by evaluations and learnings of other health and development agendas.

When comparing the prioritisation of drowning with other health issues, we found that global networks for non-communicable diseases faced similar challenges. We noted that an overt focus on technical skills had impeded non-communicable disease network formation and subsequent issue prioritisation.24 A review found that networks were most effective when civil society actors joined strong epistemic networks in broad coalitions to frame issues in ways that resonated with prevailing political priorities.25

Likewise, a comparative review of global network emergence for tuberculosis and pneumonia found that framing determined how different policy entrepreneurs identified with problem definitions that responded well to policy windows.26 Ineffective governance, limitations in diverse views on problem definition, and an unpersuasive public framing impeded the prioritisation process in urban health.27 The aforementioned analyses of network emergence point to a need for drowning-prevention actors to form diverse coalitions or networks, and negotiate and agree to framings of the problem that account for the multifarious nature of drowning.

The Shiffman and Smith framework5 provided a strong basis for analysis of the prioritisation of drowning prevention. We observed that issue characteristics provide the most persuasive explanatory factor, but actor power, ideas, and political contexts interact, intersect, and overlap as seemingly important factors in the narratives collected through in-depth interviews. As suggested by Walt and Gilson,28 our analysis might have benefited from consideration of conflict (between actor power, problem definitions, or priority solutions) as a domain. Conflict as a domain is currently not specified in the Shiffman framework. Further focus on conflict might have identified reasons or barriers to earlier prioritisation of drowning prevention. We did not identify a single structured guiding institution; rather, an informal, loosely aligned group of committed actors were observed to drive the agenda. Perhaps the small group reduced the risk of conflict and was an enabler in the prioritisation process. Sources of power and influence on policy prioritisation warrant further analysis. The absence of media as an actor constituency is common in other studies,28 although we note that media's power to frame discourse and reach mass audiences was recognised by commissioned pieces authored by the prime minister of Bangladesh and the president of Ireland, and published in global media after the UN resolution.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the under-representation of LMIC informants is perhaps a reflection on which countries drive the agenda for drowning prevention (and indeed global health).29 There is scarce research conducted outside of HICs or a small group of LMICs in Asia. Although Bangladesh, China, India, and Pakistan accounted for 51·2% of global drowning deaths in 2017,30 an analysis of drowning-focused publications found a gross under-representation of studies from LMICs (<15%).19 To address these limitations, we interviewed academics involved in research in Bangladesh, China, and Uganda. All non-academic informants were involved in global and LMIC initiatives. High refusal rates for key policy informants are not uncommon, so we added other methods, such as review of official statements and interviews with technical contributors, to the process.

Secondly, there is potential for position and recall bias, as authors J-PS and DRM were involved in the prioritisation process. However, the presentation of the findings uses framework analysis to mitigate researcher subconscious bias. The inclusion of insider and outsider perspectives in the author group and recruitment of informants across key constituencies sought to address this potential limitation and strengthen the study.

Conclusion

Our analysis informs efforts to raise attention for other neglected health issues. This study reinforces the importance of framing an issue in ways that align to external priorities, navigating political contexts to avoid controversial policy areas, and ensuring that technical debates do not override the need for simple and compelling advocacy. Ensuring that the UN resolution is a catalyst for action requires drowning prevention proponents to position drowning within global health and sustainable development agendas, strengthen capacity for multisectoral action, expand efforts for measuring drowning burden and identifying solutions across diverse contexts, and incorporate inclusive global governance, commitments, and mechanisms that hold stakeholders to account. Sustained political momentum should be enhanced by safeguarding a place in decision making for individuals most susceptible to drowning.

Declaration of interests

J-PS is employed by the Royal Life Saving Society–Australia and acts as drowning prevention commission chair for the International Life Saving Federation. J-PS is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. RN receives salary support from The George Institute for Global Health and Imperial College London. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank those who participated in the in-depth interviews, and who reviewed and provided feedback on the Results section of this study. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

J-PS and JJ developed the research idea. J-PS conducted the in-depth interviews. JJ and J-PS conducted document review. J-PS analysed the data and drafted the manuscript with the support of JJ. RN, KB, and DRM provided input into manuscript drafts. J-PS and JJ accessed and verified the data. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Meddings DR, Scarr J-P, Larson K, Vaughan J, Krug EG. Drowning prevention: turning the tide on a leading killer. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e692–e695. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00165-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UN General Assembly (75th session: 2020–21). Global drowning prevention: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly. April 29, 2021. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3925005?ln=en

- 4.Collier D. Understanding process tracing. PS Polit Sci Polit. 2011;44:823–830. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiffman J, Smith S. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet. 2007;370:1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobusingye O, Guwatudde D, Lett R. Injury patterns in rural and urban Uganda. Inj Prev. 2001;7:46–50. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baqui AH, Black RE, Arifeen SE, Hill K, Mitra SN, al Sabir A. Causes of childhood deaths in Bangladesh: results of a nationwide verbal autopsy study. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:161–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyder AA, Arifeen S, Begum N, Fishman S, Wali S, Baqui AH. Death from drowning: defining a new challenge for child survival in Bangladesh. Inj Control Saf Promot. 2003;10:205–210. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.4.205.16779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobusingye O, Tumwesigye NM, Magoola J, Atuyambe L, Olange O. Drowning among the lakeside fishing communities in Uganda: results of a community survey. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2017;24:363–370. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2016.1200629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta M, Bhaumik S, Roy S, Panda RK, Peden M, Jagnoor J. Determining child drowning mortality in the Sundarbans, India: applying the community knowledge approach. Inj Prev. 2021;27:413–418. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman F, Bose S, Linnan M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an injury and drowning prevention program in Bangladesh. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1621–e1628. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Preventing drowning: an implementation guide. [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2021. WHO Guideline on the prevention of drowning through provision of day-care and basic swimming and water safety skills. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodd M, Zwi A, Rahman A, Chowdhury FK, Ivers RQ, Jagnoor J. Keeping afloat: a case study tracing the emergence of drowning prevention as a health issue in Bangladesh 1999–2017. Inj Prev. 2021;27:300–307. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO . World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia; New Delhi: 2021. Regional status report on drowning in South-East Asia. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila: 2021. Regional status report on drowning in the Western Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linnan M, Giersing M, Cox R, et al. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; Florence: 2007. Child mortality and injury in Asia: an overview. [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. World report on child injury prevention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarr J-P, Jagnoor J. Mapping trends in drowning research: a bibliometric analysis 1995–2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagnoor J, Gupta M, Ul Baset K, Ryan D, Ivers R, Rahman A. The association between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) conditions and drowning in Bangladesh. J Water Health. 2019;17:172–178. doi: 10.2166/wh.2018.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiffman J. Four challenges that global health networks face. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2017;6:183–189. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagnoor J, Kobusingye O, Scarr J-P. Drowning prevention: priorities to accelerate multisectoral action. Lancet. 2021;398:564–566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.UN General Assembly . United Nations; New York, NY: 2015. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heller O, Somerville C, Suggs LS, et al. The process of prioritization of non-communicable diseases in the global health policy arena. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34:370–383. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SL. Factoring civil society actors into health policy processes in low- and middle-income countries: a review of research articles, 2007–16. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34:67–77. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quissell K, Berlan D, Shiffman J, Walt G. Explaining global network emergence and nonemergence: comparing the processes of network formation for tuberculosis and pneumonia. Public Adm Dev. 2018;38:144–153. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shawar YR, Crane LG. Generating global political priority for urban health: the role of the urban health epistemic community. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:1161–1173. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walt G, Gilson L. Can frameworks inform knowledge about health policy processes? Reviewing health policy papers on agenda setting and testing them against a specific priority-setting framework. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(suppl 3):iii6–ii22. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buse K, Hawkes S. Health post-2015: evidence and power. Lancet. 2014;383:678–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61945-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franklin RC, Peden AE, Hamilton EB, et al. The burden of unintentional drowning: global, regional and national estimates of mortality from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. Inj Prev. 2020;26(suppl 1):i83–i95. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.