Abstract

The microsporidia have recently been recognized as a group of pathogens that have potential for waterborne transmission; however, little is known about the effects of routine disinfection on microsporidian spore viability. In this study, in vitro growth of Encephalitozoon syn. Septata intestinalis, a microsporidium found in the human gut, was used as a model to assess the effect of chlorine on the infectivity and viability of microsporidian spores. Spore inoculum concentrations were determined by using spectrophotometric measurements (percent transmittance at 625 nm) and by traditional hemacytometer counting. To determine quantitative dose-response data for spore infectivity, we optimized a rabbit kidney cell culture system in 24-well plates, which facilitated calculation of a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) and a minimal infective dose (MID) for E. intestinalis. The TCID50 is a quantitative measure of infectivity and growth and is the number of organisms that must be present to infect 50% of the cell culture wells tested. The MID is as a measure of a system's permissiveness to infection and a measure of spore infectivity. A standardized MID and a standardized TCID50 have not been reported previously for any microsporidian species. Both types of doses are reported in this paper, and the values were used to evaluate the effects of chlorine disinfection on the in vitro growth of microsporidia. Spores were treated with chlorine at concentrations of 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 mg/liter. The exposure times ranged from 0 to 80 min at 25°C and pH 7. MID data for E. intestinalis were compared before and after chlorine disinfection. A 3-log reduction (99.9% inhibition) in the E. intestinalis MID was observed at a chlorine concentration of 2 mg/liter after a minimum exposure time of 16 min. The log10 reduction results based on percent transmittance-derived spore counts were equivalent to the results based on hemacytometer-derived spore counts. Our data suggest that chlorine treatment may be an effective water treatment for E. intestinalis and that spectrophotometric methods may be substituted for labor-intensive hemacytometer methods when spores are counted in laboratory-based chlorine disinfection studies.

Several factors have combined to place microsporidia on the Environmental Protection Agency's contaminant candidate list. Because microsporidium-related illnesses are being reported in increasing numbers, it is thought that the true prevalence of these organisms is underestimated. In immunocompromised humans, the illnesses are severe, and there is no chemotherapeutic cure for the most common infecting species at this time. In addition, as a group, the microsporidia are common environmental organisms that have the potential to cause infection if they escape filtration and water treatment in municipal water supplies. At present, accurate risk assessment is impossible. The potential for waterborne outbreaks cannot be assessed until we have more information concerning the life cycle of microsporidia in humans and disinfection parameters for microsporidia.

The microsporidium group is a large group of obligately intracellular parasites that form environmentally resistant, infectious spores. Approximately 143 genera and more than 1,200 species are known, and these organisms infect members of almost every class of vertebrates and invertebrates that has been described (61). At least 14 species are known to infect humans. Most human infections are associated with late stages of human immunodeficiency virus infection and are responsible for a variety of systemic and nonsystemic diseases (19, 26, 35, 61). The most common symptom associated with infection is diarrhea, which mimics the diarrhea resulting from infection with Cryptosporidium parvum (11, 12, 35, 58). Variability in the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic treatment contributes to the high mortality rate in AIDS patients with microsporidial illnesses (6, 14, 16, 20, 43, 45).

It is suspected that human microsporidia are transmitted environmentally, like nonhuman species, but despite reports of microsporidian DNA in water supplies (23, 46), there have been few reports of human infection associated with water sources (24, 31). In one epidemiological study, performed in the United States, the workers determined the prevalence of illness due to microsporidia and found no seasonal variation (15).

Of primary concern are the microsporidian species that infect the human gastrointestinal tract, Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon syn. Septata intestinalis. These two species are the human-infecting species that are most commonly isolated from clinical specimens, and because of their small size (1.5 to 2 μm), they present a special challenge to the water treatment industry with regard to detection and filtration. Species identification is also difficult, since the methods used for microscopic and molecular characterization of the organisms are limited (8, 11, 26, 58, 60).

Despite the limited epidemiological evidence that waterborne transmission of microsporidia occurs in municipal water systems, there is still some concern about the potential for waterborne outbreaks. Surface waters are common environmental sources of microsporidia (7). Large numbers of microsporidian spores can be introduced into the environment from stools, urine, or respiratory secretions of infected hosts. Spores are typically able to survive and remain infective for weeks, infecting nonhuman hosts through ingestion or direct inoculation (11, 19, 27). In distilled nonchlorinated water, some spores can survive temperature extremes, variations in pH, and multiple freeze-thaw cycles and remain viable for up to 10 years (3, 19, 56, 58). In order for waterborne transmission to occur in municipal water systems, microsporidia would have to survive typical water treatment processes, such as chlorination.

Because of the potential impact of microsporidia as disease-causing agents and the widespread use of chlorine in water treatment, this study was undertaken in order to develop methods that could be used for standardized viability studies of the human-infecting microsporidia and produce quantitative data as reference measures of viability before and after disinfection. Specifically, in this study we examined using an in vitro assay to assess the viability of one human microsporidium, E. intestinalis, after disinfection with chlorine, a common disinfectant used in municipal water supplies.

Cell culture procedures were optimized and standardized. Dose-response data were analyzed and yielded a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) and a minimal infective dose (MID), both of which are quantitative measures of spore infectivity. Using an in vitro 24-well plate cell culture model to monitor spore viability before and after chlorine treatment, we determined that 2 mg of chlorine per liter has an inhibitory effect on the infectivity of E. intestinalis after 16 min of exposure, which results in a >3 log reduction in spore growth. Additionally, we compared an alternative spore enumeration method to traditional hemacytometer-based counting methods. This report is the first report of a human microsporidian species that is sensitive to chlorine at concentrations applicable to a potable water supply and provides reference methods for additional studies in which other disinfectants and other microsporidian species could be used.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism, cell culture, and media.

Spores of a duodenal isolate of E. intestinalis, ATCC 50603, were maintained in 225-cm2 culture flasks (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) containing mycoplasma-free RK-13 (ATCC CCL-37) rabbit kidney cells. The cells were grown to confluency and were maintained in RPMI medium (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 7% fetal bovine serum (Omega, Tarzana, Calif.), penicillin (100 IU/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and fungizone (0.25 μg/ml; Biowhittaker, Walkersville, Md.). The cells were incubated at 35°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 with humidity. Each week for 4 weeks after infection, spores were harvested by removing the culture medium from the cell monolayers. The cell monolayers were immediately replenished with fresh culture medium. The harvested fluid was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature in 50-ml polypropylene tubes (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) by using a Sorvall model T6000B centrifuge and a type H100B rotor. After centrifugation, spent medium was removed from the spore pellets by aspiration. Spores were reintroduced into the original cell culture flasks and reincubated as described above. After 4 weeks, each 225-cm2 flask produced more than 109 spores. The identity of the species was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy and by PCR and subsequent partial sequencing of the small-subunit RNA gene (62).

Preparation of spores.

Spores were harvested from the cell monolayers and pelleted as described above. Cell debris was removed from the spore pellets by using differential density gradient centrifugation with an isopycnic gradient of Percoll (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.), an inert substance unlikely to interfere with spore germination (33, 42, 52). Equal volumes of Percoll and a spore pellet were mixed with sterile NANOpure water (Barnstead Thermolyne, Irvine, Calif.) in a 15-ml conical polypropylene tube. The resulting mixture had a specific gravity of 1.067, which was suitable for separating intact spores from empty spore coats and cell culture debris. Tubes containing the spore-Percoll mixture were centrifuged at room temperature at 2,300 × g for 30 min. The pellet, which contained purified spores, was washed with sterile NANOpure water, centrifuged again at 1,000 × g, and resuspended in sterile NANOpure water. A hemacytometer (Neubauer-ruled Bright Line counting chambers; Hausser Scientific, Horsham, Pa.) was used to count the spores (n = 4); the spore concentration was adjusted to 109 spores/10 ml of water, and the spores were recounted (n = 4) to ensure that the spore density was correct and stored at 4°C until they were used. All spores were harvested, purified, and used within 1 week of harvesting.

Comparison of hemacytometer counts and %T results.

Spore suspensions were prepared in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7), the spores were counted with hemacytometers, and the concentrations were adjusted to four different target concentrations ranging from 106 to 2 × 107 spores/ml. Target concentrations were placed in 10-ml glass tubes (Comar Glass Manufacturing, Vineland, N.J.). Using a model DR/2010 spectrophotometer (Hach, Loveland, Colo.), we measured the percent transmittance (%T) at 625 nm for each concentration (n = 12) as recommended for the procedure used to test the turbidity of latex bead McFarland equivalence turbidity standards (REMEL, Lenexa, Kans.). Mean %T values were calculated for each spore concentration. Multiple spore counts (n = 12) were obtained with hemacytometers, and mean spore counts were calculated. Data were tested for normal distribution by using residual and normal probability plots produced by a regression analysis (Microsoft Excel 97; Microsoft, Seattle, Wash.). Confidence intervals were calculated for each data set. A standard curve was constructed by plotting mean %T values versus mean spore counts. A linear regression analysis of the data was performed by using the least-squares method to produce a best-fit curve defined by a numerical equation and an R2 value that provided correlation analysis for the standard spore concentration curve. The equation for the least-squares regression line was used to predict unknown spore concentrations based on the %T data for the spore suspensions. Each spore suspension obtained in subsequent chlorine disinfection experiments was tested in a similar manner in order to determine %T values (n = 3) and hemacytometer counts (n = 2). A %T-derived spore concentration was calculated based on the linear regression analysis equation for the spore concentration standard curve. To assess the similarity of hemacytometer counts and %T-derived counts, sample means were compared by using confidence intervals (18).

Chlorine disinfection protocol.

An inoculum consisting of 109 spores in 100 ml of 0.05 M phosphate buffer was used for each chlorine test and for each control. Chlorine-demand-free (CDF) glassware was used for the chlorine treatments (34). Test and control spores were mixed at the same velocity in separate borosilicate glass beakers. The beakers contained CDF 0.05 M phosphate buffer supplemented with no chlorine (control) or chlorine at target concentrations ranging from 2 to 10 mg/liter. Chlorinated CDF buffer was prepared by adding reagent grade sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) to sterile NANOpure water to obtain the desired chlorine concentration. Chlorine levels were adjusted to compensate for any chlorine demand exerted by the spore inoculum. Chlorine concentrations were determined by using the N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine colorimetric method (5). Beakers containing CDF buffer were used as the controls. The exposure times ranged from 0 to 80 min (T0 to T80) at 25°C and pH 7. After treatment, 10-ml portions were removed from the treatment beakers and placed in sterile glass spectrophotometer tubes containing 10 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) (Fisher Scientific) to neutralize the chlorine. The 10-ml samples were used to determine spore density and for subsequent inoculation into cell cultures for viability studies. Duplicate experiments were performed for most time points and chlorine concentrations, as described previously; the only exception was the T20 exposure at 2 mg of chlorine per liter, which was performed in quadruplicate. Replicate values were calculated in order to produce results with 90% power to detect a 3-log reduction in spore viability with an α value of 0.05 (18).

In vitro microwell plate viability assay to determine infectivity.

Cell culture conditions that were optimized in our laboratory were used to determine viability and infectivity. Passage 190 RK-13 cells were grown by using a 24-well plate format. Cells were removed from cell culture flasks with trypsin-EDTA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) at 35°C. Cell counting was performed in duplicate by using a hemacytometer. Cells were diluted in cell culture medium to a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/ml. Multiwell plates were seeded by placing 1-ml portions of cell suspensions onto 15-mm2 Thermanox coverslips, which covered the surfaces of the wells in the 24-well plates. The plates were incubated at 35°C in the presence of 5% CO2 with humidity for 3 days, a time period predetermined to produce almost confluent monolayers; the cells were near the end of the logarithmic growth phase when spores were inoculated.

After disinfection with chlorine, 10-ml portions of spore suspensions were removed from treatment beakers and used for in vitro viability tests as described above. For each spore count determined in duplicate with a hemacytometer, a %T value for the spore suspension at 625 nm was also determined (n = 3). Chlorine-treated spores at a target concentration of 107 spores/ml were diluted in 0.05 M phosphate buffer, and 10-fold (log) dilutions ranging from 1:10 to 1:100,000 were prepared. One milliliter of each dilution was inoculated onto previously seeded RK-13 cell monolayers, grown on coverslips as described above, and replenished immediately before inoculation of spores along with 1 ml of 2× minimal essential medium (Sigma) containing 3.5% fetal bovine serum. Adding a spore suspension in 0.05 M phosphate buffer resulted in medium at the recommended concentration (1×) except for the extra phosphates present in the buffer.

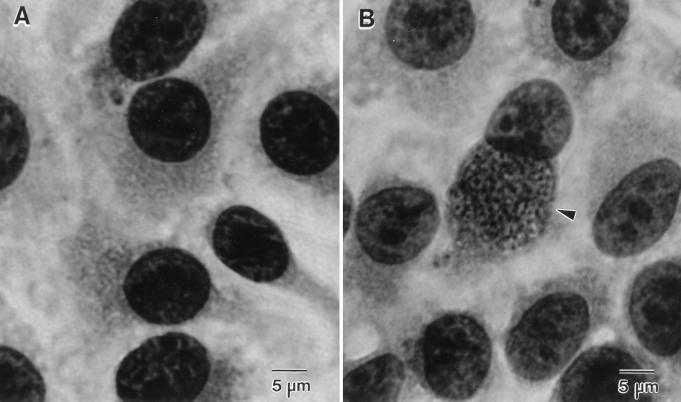

Six coverslips were inoculated for each spore dilution. Control spores were inoculated in the same way except that doubling dilutions were prepared and the spore suspension dilutions ranged from 1:1,000 to 1:128,000. Triplicate controls were prepared. Immediately after inoculation, the 24-well plates were centrifuged at 2,300 × g for 10 min, and then they were incubated at 35°C in the presence of 5% CO2 with humidity for 6 days. After incubation, the coverslips were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa stain (Hema 3 stain set; Fisher Scientific), mounted with Gel/Mount (Biomedia Corp., Foster City, Calif.) on glass slides, and examined with a light microscope. Each entire coverslip was scanned at a magnification of ×400 to determine whether parasitophorous vacuoles containing mature microsporidian spores were present in the cytoplasm of RK-13 cells (Fig. 1). The presence of one or more infected cells per coverslip was considered evidence that infection and development of E. intestinalis occurred. If no infected cells were observed, the coverslip was considered negative. The percentage of infectivity was calculated by dividing the number of positive (infected) wells by the total number of wells inoculated.

FIG. 1.

Giemsa-stained RK-13 cell monolayers. (A) Typical appearance of uninfected RK-13 cells. (B) RK-13 cell with a cytoplasmic vacuole containing E. intestinalis parasites (arrowhead).

Dose-response and log10 reduction calculations.

Dose-response curves were plotted by using percentage of infectivity as the independent variable. The mean spore count per well was calculated by combining data from three control experiments performed within a 1-week period and averaging all spore counts for inocula that produced the same infectivity value. Data were analyzed by using both hemacytometer-derived and %T-derived spore counts. Standard deviations and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated for hemacytometer and %T-derived spore counts. After we plotted the mean number of spores per well versus percentage of infectivity, a linear regression analysis was performed by using the least-squares method. The least-squares regression of the data produced a best-fit curve, which was defined by a numerical equation that represented the slope of the line describing the dose-response model, and an R2 value that provided a correlation value for the dose response. The equation for the least-squares regression line was used to calculate the TCID50 of control spores used during the experiments. The equation for the regression line represented the equation describing the dose-response model. Percentages of growth inhibition and log10 reductions were calculated by comparing values to the values obtained for the lowest dilution of control spores that still produced an infection (i.e., the MID). By using 95% confidence intervals (18) to measure variability about the mean, the MID of chlorine-treated spores were compared to the MID of control spores.

RESULTS

Hemacytometer counts versus %T-derived counts.

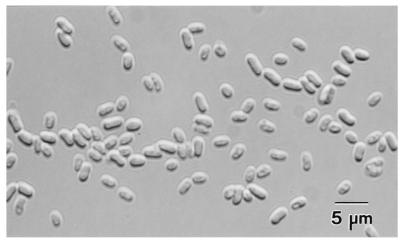

After purification as described above, spore suspensions were free of debris and suitable for subsequent spectrophotometric measurement (Fig. 2). The level of spore recovery after purification was more than 65%.

FIG. 2.

Differential interference contrast microscopy of E. intestinalis spores after Percoll purification. Magnification, ×320.

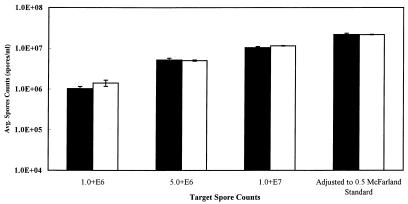

For target spore counts of 1 × 106, 5 × 106, and 1 × 107 spores/ml and the equivalent of a 0.5 McFarland standard, the mean hemacytometer spore counts were 1.0 × 106, 5.2 × 106, 1.0 × 107, and 2.2 × 107 spores/ml, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3), which also shows the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Data were normally distributed around the mean, as determined by residual and normal probability plots obtained by using the linear regression statistical model (25) and Microsoft Excel 97. Spectrophotometric measurement (%T at 625 nm), performed with the same spore suspensions, resulted in mean values ranging from 78.46 to 98.53 with 95% confidence intervals ranging from 0.19 to 0.33. A standard curve was prepared by plotting mean %T versus mean number of spores per milliliter. A least-squares regression analysis of the standard curve data produced an equation (y = −1E + 06χ + 1E + 08) with an R2 correlation value of more than 0.99. The regression equation was used to calculate %T-derived counts from the %T data. The calculated %T-derived counts and the corresponding 95% confidence limits are shown in Fig. 3. In all cases except the 1.0 × 106-spores/ml target value, the means for the %T-derived counts were within the range of the 95% confidence limits for the hemacytometer counts.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of hemacytometer and %T-derived spore counts for E. intestinalis. Average hemacytometer counts (n = 12) were compared with counts derived from a standard curve prepared by plotting counts versus T% values (625 nm) obtained with the same spore sample (n = 12). The error bars indicate 95% confidence limits. Open bars, %T-derived counts; solid bars, hemacytomer counts.

Control spores: dose response, TCID50, and MID.

After they were subjected to experimental conditions, the control spore preparations had hemacytometer-derived spore concentrations of 9.5 × 106 ± 2.7 × 106 spores/ml (mean ± standard deviation) and %T-derived concentrations of 8.4 × 106 ± 1.5 × 106 spores/ml. Since the original inoculum concentration was 1 × 107 spores/ml, the levels of spore recovery were 95 and 84%, respectively.

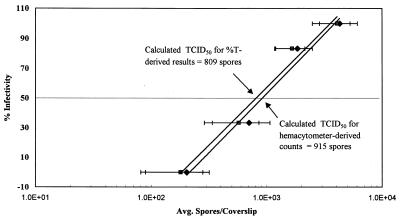

The calculated postdilution mean hemacytometer counts and %T-derived spore counts are shown in Fig. 4 as a function of the corresponding percentages of infectivity in 24-well RK-13 cell culture plates (n = 3). A least-squares regression analysis of the hemacytometer and %T-derived data produced the equations y = 34.628ln(x) − 186.13 and y = 33.764ln(x) − 176.05, respectively. Each of these equations has a corresponding R2 value of 0.98. The regression analysis equations represent the linear dose responses for control E. intestinalis spores inoculated into RK-13 cells when a centrifuged 24-well plate format was used. Using both the hemacytometer-derived and %T-derived regression equations, we calculated that the TCID50 for E. intestinalis were 915 and 809 spores/well, respectively. In all cases, the mean %T-derived counts were within the 95% confidence limits of the hemacytometer counts, and the data sets were determined to be equivalent.

FIG. 4.

Dose-response model for infectivity of E. intestinalis in RK-13 cells. A dose-response curve was prepared for E. intestinalis in phosphate buffer (n = 2 to 5). The regression lines and TCID50 calculated from %T-derived counts are equivalent, as determined by using 90% confidence limits. The equation for the %T-derived regression line is y = 33.764ln(x) − 176.05 (R2 = 0.98), and the equation for the hemacytometer count line is y = 34.628ln(x) − 186.13 (R2 = 0.98). Symbols: ⧫, hemacytometer counts; ■, %T-derived counts. The solid lines are calculated regression lines, and the dotted line indicates the calculated TCID50.

Chlorine-treated spores: log reduction.

A free chlorine concentration of 2 mg/liter was the lowest target concentration tested with which a significant reduction in spore viability was observed. During disinfection experiments in which the target concentration was 2 mg of free chlorine per liter, the total and free chlorine concentrations ranged from 3.22 to 3.92 mg/liter and from 2.58 to 2.98 mg/liter, respectively, when the exposure time was zero. Concentrations higher than the target concentrations were used in order to compensate for the large chlorine demand of the spores.

After they were subjected to experimental conditions, the chlorine-treated spore preparations had hemacytometer-derived spore concentrations of 1.0 × 107 ± 1.3 × 106 spores/ml (mean ± standard deviation) and %T-derived concentrations of 8.8 × 106 ± 6.90 × 106 spores/ml. Since the original target inoculum concentration was 1 × 107 spores/ml, the levels of chlorine-treated spore recovery were 100 and 88%, respectively.

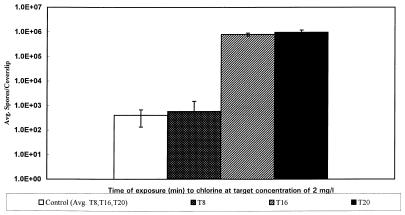

Figure 5 shows the log10 reduction data for E. intestinalis spores exposed to 2 mg of chlorine per liter in 0.05 M CDF phosphate buffer at 25°C and pH 7. For hemacytometer-derived and %T-derived data, a reduction in growth of more than 3 logs (>99.9% inactivation) was observed after exposure for at least 16 min at a chlorine concentration of 2 mg/liter. Reductions of more than 3 logs were also observed at T20, T40, and T80 with 5 and 10 mg of chlorine per liter (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effect of chlorine exposure (2 mg/liter) on the MID of E. intestinalis in RK-13 cells. A >3-log reduction in the infectivity of E. intestinalis was observed after exposure to chlorine for 16 and 20 min. No infection occurred even at doses that were more than 3 logs higher than the control MID. The error bars indicate the 95% confidence limits. The T16 and T20 values are the maximum spore counts that can be accurately tested with this system. The actual MID may be greater than the value shown.

Mean MID results showing the reductions in the viability of spores treated with 2 mg of chlorine per liter (T16 and T20) are presented graphically in Fig. 5 along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. This figure shows the differences between the MID of the control spores and the MID of chlorine-treated spores. The control spores produced infection at significantly lower doses than the chlorine-treated spores produced infection.

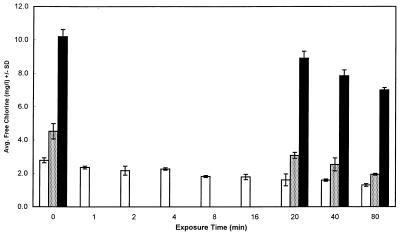

Figure 6 shows the decay of residual chlorine over time, as observed in all of the chlorine experiments which we performed. Despite the large chlorine burden of spores in suspension at high concentrations, this data demonstrates that it was possible to approach or exceed target chlorine concentrations when chlorine was added to Percoll-purified spore suspensions.

FIG. 6.

Final free chlorine concentrations for three disinfection targets during chlorine disinfection testing for E. intestinalis. Average free chlorine concentrations at the end of the exposure periods for all target chlorine concentrations were determined. Open bars, 2 mg of chlorine per liter; stippled bars, 5 mg of chlorine per liter; solid bars, 10 mg of chlorine per liter.

DISCUSSION

Previous infectivity, disinfection, and drug susceptibility studies have been performed by using a variety of techniques. These techniques include traditional “growth-no growth” models, enumeration of infective foci in stained cell monolayers, and spore germination to assess the effects of laboratory disinfectants or drugs on the subsequent growth and infective capabilities of microsporidia (9, 17, 21, 32, 36, 42, 44, 51, 53, 56, 59). More recently, vital dye loading and subsequent scanning confocal microscopy have been used (37). Various conditions and test methods made these studies labor-intensive and their results difficult to compare.

Few attempts have been made to optimize culture conditions and spore enumeration methods so that standardized quantitative assays may be used to monitor changes in the in vitro growth of microsporidia after disinfection or drug susceptibility testing (22, 40–42). In this study, an assay performed with an RK-13 cell culture system for growth of E. intestinalis proved to be a reproducible standardized assay for determining two infective doses of E. intestinalis, the TCID50 and the MID.

Because of the limited number of animal models for microsporidian growth and the low spore concentrations that can be produced in these models (1, 2, 48), we used an in vitro system to assess the effects of chlorine on the viability of microsporidia. Most, but not all, of the human-infecting microsporidia grow well in a variety of cell lines, which permits workers to use an in vitro model to evaluate organism infectivity and growth (10, 53, 55), but since E. bieneusi, the most common microsporidium that infects humans, has not been propagated so that large numbers of spores are produced in vitro (54), E. intestinalis was used as the test organism for the disinfection studies which we performed.

During the in vitro replication cycle, Encephalitozoon spp. typically form cytoplasmic parasitophorous vacuoles filled with large numbers of mature spores; these vacuoles eventually rupture and release spores into the culture medium (13, 53). The parasitophorous vacuoles can be visualized by fixing and staining infected cell monolayers with Giemsa stain before the cells rupture (9, 59). Examination of stained monolayers provides a basis for in vitro examination of infectivity and viability because cytoplasmic vacuoles filled with spores can be observed only if the spores have germinated, infected host cells, multiplied, and matured.

Centrifugation of E. intestinalis spores onto RK-13 cell monolayers in multiwell plates forced spore-to-cell contact, which increased the opportunity for spores to infect host cells. Centrifugation was intended to synchronize infection so that all of the spores had the same time in which to multiply. Infected cells contained vacuoles that were easily visible by day 6 of incubation and facilitated calculation of the MID and TCID50 without the necessity of counting spores from cell culture supernatant or foci on cell monolayers. Our data provide the first standardized MID or TCID50 values reported for any microsporidian species.

Using 24-well plates facilitated replicate testing at several chlorine concentrations and for several exposure times. Although testing with this system is labor-intensive, it is less demanding than testing with systems in which infected foci are counted or spores harvested from infected flask-based systems are counted. Using Thermanox coverslips with the 24-well plates allows permanent mounting of cell monolayers and transmission electron microscopy of cell monolayers. Our system allowed inoculation with chlorine-treated spores at concentrations as high as 106 spores/ml, which were at least 1,000 times (3 logs) greater than the MID of control spores. In vitro inoculation of organisms at concentrations greater than 106 spores/ml is not prudent since dead organisms tend to accumulate in clumps on the cell monolayer and make microscopy difficult and imprecise.

The experimental conditions used for disinfection resulted in high levels of recovery of control spores (84 to 95%) and chlorine-treated spores (89 to 100%). These high levels of recovery provided reasonable assurance that the spore populations were relatively homogeneous both before the experiment and after the experiment. The high level of recovery of chlorine-treated spores assured that the decrease in infectivity observed after chlorine treatment was due to spore death rather than to incidental spore loss.

The results obtained when the dilutions of control spores were doubled revealed that there were sequential decreases in percentages of infectivity as the spore dilution decreased. A TCID50 of 915 spores/well was calculated by using hemacytometer-derived data. When the %T at 625 nm was used to estimate the spore count, the TCID50 was 809 spores/well. Because it was not feasible to prepare twofold dilutions over the entire concentration range necessary to determine a 3-log reduction in the TCID50, 10-fold dilutions were prepared. Due to the large differences in the spore concentrations derived from the 10-fold dilutions of chlorine-treated spores, the results for treated spores did not define enough data points along the dose-response curve to calculate a valid TCID50. Likewise, TCID50 values could not be compared for T16 or longer exposure times since the inoculum did not result in any infection even at the highest concentrations. However, 10-fold dilutions proved to be adequate for comparing the MID of chlorine-treated spores with the MID of control spores. These doses were calculated before and after chlorine disinfection in order to assess the potential effectiveness of chlorine disinfection. Using MID comparisons, we observed a >3-log10 reduction in spore viability after chlorine treatment at T16. Considering that the MID for chlorine-treated spores at T16 and T20 represent the maximum detection limit of the RK-13 cell system, the actual log10 reduction values may be even greater than the value on the graph.

Many variables affect the results of an in vitro assay. In our study we performed tests in an attempt to optimize centrifugation, the age of cells, the cell density, and the method used for spore purification and enumeration. Other key variables, such as the source of fetal bovine serum, the pH of the medium, and medium supplements, may alter the results obtained. Changes in the serum supplier and changes in other reagents may change the TCID50 of E. intestinalis (unpublished results); therefore, it is imperative that standard conditions are maintained throughout the entire experiment. In addition, it has been noted that changes in the preexperiment growth conditions for other organisms may influence the sensitivity of the organisms to disinfectants (29), so it is reasonable to assume that the same issues may exist for microsporidia. As changes are made, it will be important to evaluate each set of experiments with the MID and TCID50 determined under the conditions used.

Another aspect of this study was the use of spectrophotometric turbidity to measure various spore concentrations in order to prepare a standard curve that was used as a substitute for enumeration of microsporidia by hemacytometer counting. The hemacytometer counts used for enumeration were very variable (28, 47) due to small differences in pipetting, loading of the chamber, and specimen mixing. Alternatively, the turbidity due to organisms in suspension can be measured and compared with the turbidity of latex bead or barium sulfate McFarland standards. In this study turbidity was measured with a spectrophotometer by using %T at 625 nm, which could be correlated with organism concentration if the preparations were pure and free of debris that could interfere with accurate turbidity measurements. Spectrophotometric enumeration is currently used as a substitute for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial hemacytometer counting in protocols designed for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (4, 30, 38, 39). Spectrophotometric measurements have not been used previously to enumerate microsporidia but have been used to measure spore germination rates (49) and changes in internal sugar concentrations related to viability (50, 52). The small size and uniform density of microsporidia make them logical organisms for enumeration with a %T-based method.

Using %T readings for spore enumeration resulted in mean spore counts that were similar to mean hemacytometer-derived spore counts with respect to concentration and variability about the mean. The results, including the results for log10 reductions in viability, were not significantly different when %T-derived spore counts were used. It appears that %T values can be used to enumerate E. intestinalis spores in phosphate buffer when predicted spore concentrations range from 5.0 × 106 to 2.18 × 107 spores/ml. Because %T values did not correlate well with hemacytometer-derived spore counts at concentrations less than 5 × 106 spores/ml, %T should not be used to measure spore concentrations when the concentrations are less than this threshold value. The lack of a correlation may be due to the limits of linearity inherent with spectrophotometric measurements. In addition, %T values could not be used for source waters with inherently high levels of turbidity that would interfere with spectrophotometric measurement.

For transparent, nonturbid diluents, it apparently is reasonable to use %T values as substitutes for spore counts prior to dilution and cell infection. Replacing experimental hemacytometer spore counts with %T values has the potential to limit the variation inherent in hemacytometer (47) measurements of inoculum density, which would make the TCID50 and MID values more reproducible. Further testing and statistical analysis of spore count comparisons with other disinfection systems are needed.

Spectrophotometric data may also prove to be useful for enumeration of spores after other disinfection treatments but may not be useful in all situations. One report has indicated that changes in turbidity at 625 nm measured changes in the trehalose concentration which occurred as spore viability decreased (52). Using chlorine as a disinfectant did not result in noticeable changes in spore density determined at 625 nm. Values for spores proven to be nonviable in this model system did not differ significantly from the %T values for control spores. However, any disinfectant or treatment that affects spore viability and causes corresponding changes to the internal sugar content may yield false results if only %T values are used to enumerate spores. Comparisons of hemacytometer counts and counts derived from %T values may help determine the mechanism of spore death if changes in density indicate that there are changes in sugar concentration.

The multiwell RK-13 cell assay has potential uses in a variety of situations. Because RK-13 cells are easily cultivated and rapid growth of Encephalitozoon sp. occurs with these cells, the system can facilitate assessment of quantitative effects of cell culture variables on the growth of E. intestinalis or other microsporidia. Quantitative parameters such as these can serve as a baseline for future cell culture modifications and growth enhancements aimed at producing even lower MID and TCID50 values. Awareness of these conditions may eventually facilitate in vitro growth of the microsporidian species that currently cannot be cultivated by traditional methods. TCID50 and MID can also be used to assess other disinfection parameters and the antibiotic susceptibility of microsporidia.

Although the effects of all in vitro variables have not been assessed yet, the system is still a useful model for comparative purposes and for evaluating disinfection parameters. Optimum disinfection levels could be reached by using spore suspensions prepared by Percoll purification. Labor-saving spectrophotometric methods proved to be adequate for determining spore concentrations near 107 spores/ml, the approximate concentration of control and chlorine-treated spore preparations in the test system. Most importantly, this system produced data from which a >3-log10 reduction could be calculated after treatment with chlorine.

More testing will be necessary as further optimization is required and to determine the effect of source water on chlorine disinfection capabilities. Studies in which laboratory water and buffers are used are helpful for determining disinfection parameters and ranges, but definitive conclusions about the effect of chlorine on microsporidia in the environment cannot be made until source water studies have been performed.

The findings of this study may help water industry regulators begin to determine the requirements for chlorine inactivation of microsporidia. The system described here detected changes in spore viability caused by disinfection with 2 mg of chlorine per liter in phosphate buffer for 16 min. Multiplying concentration (C) by exposure time (T) results in a CT value of 32. Most water utilities provide a median residual chlorine concentration of 1.1 mg/liter after a median exposure time of 45 min, a CT value of >49, prior to the point of first use in the distribution system (57). Therefore, the results of this study indicate that chlorine treatment may prove to be a reasonable water treatment for inactivation of E. intestinalis in municipal water supplies if similar results are obtained in studies performed with natural water.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Environmental Protection Agency Analytical Service contract 8C-R202-NAEX.

We gratefully acknowledge Dick Korich for his critique of the manuscript. We also thank HACH Company, Loveland, Colo., for use of the spectrophotometer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accoceberry I, Carriere J, Thellier M, Biligui S, Danis M, Datry A. Rat model for the human intestinal microsporidian Enterocytozoon bieneusi. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44:83S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accoceberry I, Greiner P, Thellier M, Achbarou A, Biligui S, Danis M, Datry A. Rabbit model for human intestinal microsporidia. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44:82S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amigo J M, Gracia M P, Rius M, Salvado H, Maillo P A, Vivares C P. Longevity and effects of temperature on the viability and polar-tube extrusion of spores of Glugea stephani, a microsporidian parasite of commercial flatfish. Parasitol Res. 1996;82:211–214. doi: 10.1007/s004360050097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amsterdam D. Susceptibility testing of antimicrobials in liquid media. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 52–111. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the examination of water and waste water. 19th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anwar-Bruni D M, Hogan S E, Schwartz D A, Wilcox C M, Bryan R T, Lennox J L. Atovaquone is effective treatment for the symptoms of gastrointestinal microsporidiosis in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS. 1996;10:619–623. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avery S W, Undeen A H. The isolation of microsporidia and other pathogens from concentrated ditch water. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1987;3:54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker M D, Vossbrinck C R, Didier E S, Maddox J V, Shadduck J A. Small subunit ribosomal DNA phylogeny of various microsporidia with emphasis on AIDS related forms. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1995;42:564–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb05906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beauvais B, Sarfati C, Challier S, Derouin F. In vitro model to assess the effect of antimicrobial agents on Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2440–2448. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bocket L, Marquette C H, Dewilde A, Hober D, Wattre P. Isolation and replication in human fibroblast cells (MRC-5) of a microsporidian from an AIDS patient. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90052-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryan R T. Microsporidia. In: Mandel G, Bennett J E, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practices of infectious diseases. New York, N.Y: Churchill and Livingstone; 1995. pp. 2513–2524. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cali A, Owen R L. Microsporidiosis. In: Balows A, Hausler W, Lennette E H, editors. Laboratory diagnosis of infectious disease: principles and practice. New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1992. pp. 929–950. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cali A, Weiss L M, Takvorian P M. Microsporidian taxonomy and the status of Septata intestinalis. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1996;43:106S–107S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb05027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canning E U, Hollister W S. In vitro and in vivo investigations of microsporidia. J Protozool. 1991;38:631–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conteas C, Berlin O G W, Lariviere M, Pandhumas S S, Speck C E, Porschen R, Nakaya T. Examination of the prevalence and seasonal variation of intestinal microsporidiosis in the stools of persons with chronic diarrhea and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:559–561. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conteas C N, Speck C E, Berlin O G W, Pandhumas S S, Lariviere M J, Fu C. Modification of the clinical course of intestinal microsporidiosis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients by immune status and anti-human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:555–558. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curry A, Canning E U. Human microsporidiosis. J Infect. 1993;27:229–236. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(93)91923-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson-Sanders B, Trapp R G. Basic and clinical biostatistics. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Didier E S, Snowden K F, Shadduck J A. Biology of microsporidian species infecting mammals. In: Baker J R, Muller R, Rollinson D, editors. Advances in parasitology: opportunistic protozoa in humans. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 284–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dionisio D, Sterrantino G, Meli M, Trotta M, Milo D, Leoncini F. Use of furazolidone for the treatment of microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi in patients with AIDS. Recenti Prog Med. 1995;86:394–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ditrich O, Kucerova Z, Koudela B. In vitro sensitivity of Encephalitozoon cuniculi and E. hellem to albendazole. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1994;41:37S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doultree J C, Maerz A L, Ryan N J, Baird R W, Wright E, Crowe S M, Marshall J A. In vitro growth of the microsporidian Septata intestinalis from an AIDS patient with disseminated illness. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:463–470. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.463-470.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowd S E, Gerba C P, Enriquez F J, Pepper I L. PCR amplification and species determination of microsporidia in formalin-fixed feces after immunomagnetic separation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:333–336. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.333-336.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enriquez J F, Taren D, Cruz-Lopez A, Muramoto M, Palting J D, Cruz P. Prevalence of intestinal encephalitozoonosis in Mexico. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1227–1229. doi: 10.1086/520278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher D F, Van Belle G. Biostatistics and methodology for the health sciences. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia L S, Bruckner D A. Diagnostic medical parasitology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser C A, Angulo F J, Rooney J A. Animal-associated opportunistic infections among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:14–24. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grover M L, Blee E, Stokes B O. Effect of sample volume on cell recovery in centrifugation. Acta Cytol. 1997;39:387–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas C N, Karra S B. Kinetics of microbial inactivation by chlorine. I. Review of results in demand-free systems. Water Res. 1984;18:1443–1449. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hindler J. Preparation of routine media and reagents used in antimicrobial susceptibility testing. In: Isenberg H D, editor. Clinical microbiology procedure handbook. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 5.19.1–5.19.30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hutin Y J, Sombardier M N, Liguory O, Sarfati C, Derouin F, Modal J, Molina J M. Risk factors for intestinal microsporidiosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a case-control study. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:904–907. doi: 10.1086/515353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishihara R. Stimuli causing extrusion of polar filaments of Glugea fumiferanae spores. Can J Microbiol. 1967;13:1321–1332. doi: 10.1139/m67-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jouvenaz D P. Percoll: an effective medium for cleaning microsporidian spores. J Invertebr Pathol. 1981;37:319. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korich D G, Mead J R, Madore M S, et al. Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1423–1428. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1423-1428.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotler D P, Orenstein J M. Clinical syndromes associated with microsporidiosis. In: Baker J R, Muller R, Rollinson D, editors. Advances in parasitology: opportunistic protozoa in humans. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 320–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leitch G J, He Q, Wallace S, Vivesvara G S. Inhibition of the spore polar filament extrusion of the microsporidium, Encephalitozoon hellem, isolated from an AIDS patient. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:711–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leitch G J, Scanlon M, Shaw A, Visvesvara G S, Wallace S. Use of a fluorescent probe to assess the activities of candidate agents against intracellular forms of Encephalitozoon microsporidia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:337–344. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFarland J. Nephelometer: an instrument for estimating the number of bacteria in suspensions used for calculating the opsonic index and for vaccines. JAMA. 1907;49:1176–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 39.REMEL. McFarland equivalence turbidity standards. Lenexa, Kans: REMEL; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scaglia M, Sacchi L, Gatti S, Bernuzzi A M, de P. Polver P, Piacentini I, Concia E, Croppo G P, Da Silva A J, Pieniazek N J, Slemenda S B, Wallace S, Leitch G J, Visvesvara G S. Isolation and identification of Encephalitozoon hellem from an Italian AIDS patient with disseminated microsporidiosis. APMIS. 1994;102:817–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shadduck J A, Polley M B. Some factors influencing the in vitro infectivity and replication of Encephalitozoon cuniculi. J Protozool. 1978;25:496. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1978.tb04174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silveira H, Canning E U. In vitro cultivation of the human microsporidium Vittaforma corneae: development and effect of albendazole. Folia Parasitol (Prague) 1995;42:241–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon D, Weiss L M, Tanowitz H B, Cali A, Jones J, Wittner M. Light microscopic diagnosis of human microsporidiosis and variable response to octotreide. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:271–273. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90613-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith J E, Barker R J, Lai P F. Culture of microsporidia from invertebrates in vertebrate cells. Parasitology. 1982;85:427–435. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sobottka I, Albrecht H, Schafer H, Schottelius J, Visvesvara G S, Laufs R, Schwartz D. Disseminated Encephalitozoon (Septata) intestinalis infection in a patient with AIDS: novel diagnostic approaches and autopsy-confirmed parasitologic cure following treatment with albendazole. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2498–2592. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2948-2952.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sparfel J M, Sarafati C, Liguory O, Caroff B, Dumoutier N, Gueglio B, Billaud E, Raffi F, Molina J, Meigeville M, Derouin F. Detection of microsporidia and identification of Enterocytozoon beieneusi in surface water by filtration followed by specific PCR. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1997;44:78S. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Student. On the error of counting with a haemocytometer. Biometrika. 1907;5:351–360. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tzipori S, Carville A, Widmer G, Kotler D, Mansfield K, Lackner A. Transmission and establishment of a persistent infection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi, derived from a human with AIDS, in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1016–1020. doi: 10.1086/513962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Undeen A H, Avery S W. Spectrophotometric measurement of Nosema algerae (Microspora: Nosematidae) spore germination rate. J Invertebr Pathol. 1988;52:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Undeen A H, Frixione E. The role of osmotic pressure in the germination of Nosema algerae spores. J Protozool. 1990;37:561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Undeen A H, Meer R K. The effect of ultraviolet radiation on the germination of Nosema algerae, Vavra and Undeen (microsporidia: Nosematidae) spores. J Protozool. 1990;37:194–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Undeen A H, Solter L F. The sugar content and density of living and dead microsporidian (Protozoa: Microspora) spores. J Invertebr Pathol. 1996;67:80–91. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Gool T, Canning E U, Gilis H, van den Bergh Weerman M A, Eeftinck Schattenkerk J K, Dankert J. Septata intestinalis frequently isolated from stool of AIDS patients with a new cultivation method. Parasitology. 1994;109:281–289. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000078318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Visvesvara G, Leitch G J, Pieniazek N J, Da Silva A J, Wallace S, Slemenda S B, Weber R, Schwartz D A, Gorelkin L, Wilcox C M. Short-term in vitro culture and molecular analysis of the microsporidian, Enterocytozoon bieneusi. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1995;42:506–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb05896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waller T. Growth of Nosema cuniculi in established cell lines. Lab Anim. 1975;9:61–68. doi: 10.1258/002367775780994835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waller T. Sensitivity of Encephalitozoon cuniculi to various temperatures, disinfectants and drugs. Lab Anim. 1979;13:227–230. doi: 10.1258/002367779780937753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Water Quality Division Disinfection Committee. Survey of water utility disinfection practices. J Am Water Works Assoc. 1992;84:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weber R, Bryan R T, Schwartz D A, Owen R L. Human microsporidial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:426–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.4.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiss L M, Michalakakis E, Coyle C M, Tanowitz H B, Wittner M. The in vitro activity of albendazole against Encephalitozoon cuniculi. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1994;41:65S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiss L M, Vossbrinck C R. Microsporidiosis: molecular and diagnostic aspects. In: Baker J R, Muller R, Rollinson D, Tzipori S, editors. Advances in parasitology: opportunistic protozoa in humans. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 351–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wittner M, Weiss L M. The microsporidia and microsporidiosis. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolk D M. Development and application of cell culture and molecular techniques for the diagnosis, identification, and viability testing of human microsporidia. Thesis. Tucson: University of Arizona; 1999. [Google Scholar]