Abstract

Our previous review of compassion measures in healthcare between 1985 and 2016 concluded that no available measure assessed compassion in healthcare in a comprehensive or methodologically rigorous fashion. The present study provided a comparative review of the design and psychometric properties of recently updated or newly published compassion measures. The search strategy of our previous review was replicated. PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases and grey literature were searched to identify studies that reported information on instruments that measure compassion or compassionate care in clinicians, physicians, nurses, healthcare students, and patients. Textual qualitative descriptions of included studies were prepared. Instruments were evaluated using the Evaluating Measures of Patient-Reported Outcomes (EMPRO) tool. Measures that underwent additional testing since our last review included the Compassion Competence Scale (CCS), the Compassionate Care Assessment Tool (CCAT)©, and the Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale (SCCCS)™. New compassion measures included the Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others Scale (SOCS-O), a self-report measure of compassion for others; the Bolton Compassion Strengths Indicators (BSCI), a self-report measure of the characteristics (strengths) associated with a compassionate nurse; a five-item Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion (TMPACC); and the Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire (SCQ). The SCQ was the only measure that adhered to measure development guidelines, established initial construct validity by first defining the concept of interest, and included the patient perspective across all stages of development. The SCQ had the highest EMPRO overall score at 58.1, almost 9 points higher than any other compassion measure, and achieved perfect EMPRO subscale scores for internal consistency, reliability, validity, and respondent burden, which were up to 43 points higher than any other compassion measure. These findings establish the SCQ as the ‘gold standard’ compassion measure, providing an empirical basis for evaluations of compassion in routine care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40271-022-00571-1.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Patients identify compassion as one of their most important needs; a need they feel is often inadequately addressed within their experience of the healthcare system. |

| A persistent and substantial barrier to improving compassion in healthcare is the absence of a valid and reliable patient-reported measure of compassion for research and practice. |

| The Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire (SCQ) is the most valid and reliable measure of compassion, serving as a “gold standard” for conducting compassion research and assessing patients’ experiences of compassion. |

Introduction

Compassion, defined as “a virtuous response that seeks to address the suffering and needs of a person through relational understanding and action” ([1] p.195), is an enduring, central, and increasingly cited component of healthcare policy, standards of practice, healthcare organization mission statements [2–7], and the patient experience [7–14] that is crucial to patients’ and family members’ perception of quality care [8, 15–18]. Research has demonstrated that compassion enhances the overall quality of healthcare [1, 19–22] and patient outcomes, including patient quality of life and satisfaction with care [1, 8, 17, 23–31], while a lack of compassion in healthcare interactions increases adverse medical events, symptom distress, patient complaints, and malpractice suits [24, 29, 32–34]. Compassion has been reported to have a positive effect on clinician outcomes through increased job satisfaction, retention, and workplace wellbeing [19, 29, 35]. The multifactorial impacts of compassion in healthcare have caused policy makers, researchers, and educators to consider compassionate care a patient right [16], a practice competency [3, 7, 15, 36, 37], and a standard of care that healthcare organizations, providers, students, and educators are expected to measure, report, and be evaluated on [3, 17, 18, 28, 38].

Despite the mounting body of evidence that shows compassion positively impacts patients’ healthcare experiences and outcomes, compassion is reportedly receding from hospitals and healthcare training programs. Patients identify compassion as one of their most important yet unmet needs [1, 8, 13, 14, 17, 24–26], and while most healthcare providers desire to provide compassion, there is a growing gap between healthcare providers’ intentions and patients’ experiences of compassion in the fast-paced, resource-restrained, high-volume, and highly complex healthcare system with which they interact [6, 17, 28, 39, 40]. The ramifications are substantial, as a lack of compassion was a common and central factor in recent high-profile healthcare reports investigating failures within various healthcare systems [17, 28].

To date, a persistent barrier to improving compassion in healthcare is the absence of a valid and reliable measure of patient experiences of compassion, impeding the development of evidence-based training, clinical programs, research, and policy aimed at improving compassion [5, 15, 18]. Clinical measures of compassion have been developed, and comprehensive and critical reviews of validity evidence pertaining to compassion measures have been conducted [18, 29, 41–43]. Findings confirm that existing measures do not adequately adhere to measure development guidelines, lack construct validity, have limited evidence of clinical applicability, and fail to include the perspectives of patients across each stage of measure development [1, 42–45].

Our previous review of compassion measures in healthcare between 1985 and 2016 concluded that no single measure available measured compassion in healthcare in a comprehensive or sufficiently methodologically rigorous fashion [42]. Since then, additional testing has been conducted on several measures and new compassion measures have been proposed [46–58]. The objective of the present study was to provide a critical and comparative review of the design and psychometric properties of recently updated or newly published compassion measures to identify a “gold standard” for measuring compassion in healthcare research, clinical practice, and healthcare policy development.

Methods

Study Design

A comprehensive review of the compassion measure literature was conducted. Our previous search [42] was updated, and relevant compassion measures were compared using a narrative synthesis approach and evaluated using the Evaluating Measures of Patient-Reported Outcomes (EMPRO) tool, a validated tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported outcome measures [59]. While a number of different critical appraisal tools exist for patient-reported outcome measures, the EMPRO was specifically designed to evaluate and compare patient-reported outcome measures themselves, producing standardized global scores of measure properties [59–63]. As identified in a number of recent systematic reviews [60, 61, 64–66], this is a distinguishing feature and rationale for selecting the EMPRO, in comparison to other tools such as the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist, which assesses the quality of the methodological design of each study, but not the quality of the measure itself [63].

Literature Search

The search strategy of our previous review was replicated [42]. An initial search of the literature using the electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO was conducted by one of the authors (JK) under the direction of the research team (SS, TH, HB, CM), which was comprised of compassion and measurement experts. The initial search was broad and included the search terms “compassion,” “compassionate care,” “measure,” “instrument,” “scale,” “model,” and “tool.” In a second search, the search term “compassion” was combined with a pre-existing search filter that was developed and validated for the specific purpose of finding studies on the psychometric properties of measurement instruments in PubMed [67] (see the electronic supplementary material for the Pub Med search strategy). Forward citation searches of included studies using Web of Science and grey literature searches of relevant organizational websites were conducted. The search was restricted to studies in the English language published between January 2013 and May 2021. The search was extended back to 2013 to ensure adequate overlap between this and the previous review, which included studies published between 1985 and 2016 [42].

To ensure fidelity between the previous search and the current search, the same inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted [42]. Namely, studies were included in the final synthesis if they reported on instruments for the measurement of compassion or compassionate care in samples of clinicians, physicians, nurses, healthcare students, and patients. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) qualitative or mixed-method studies; (2) studies that focused on related concepts such as empathy, sympathy, pity, self-compassion, compassion fatigue, fear of compassion, and compassion satisfaction; (3) neurological and neuroplasticity research that reported on psychophysiological changes in response to non-verbal communication of compassion; and (4) letters, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts, and case studies [42].

Two review authors (SS, JK) examined titles and abstracts to select eligible studies and reviewed the full text of potentially relevant studies to determine which studies met the inclusion criteria, with any disagreements being resolved through discussion until consensus was met. One review author (JK) extracted data from eligible studies. Information was collated in a tabular form, including first author’s last name, year of publication, and a description of the compassion measure, including number of items, subscales, and psychometric properties. Compassion measures were classified as healthcare provider-reported measures or patient-reported measures.

Data Synthesis

A narrative describing the compassion measures was developed. Measurement properties referred to in measure development guidelines [59, 63, 68], including criteria relevant to the construct and the populations that the measure is intended to assess, and the measure’s reliability, validity, responsiveness, interpretability, and feasibility were considered.

Comparative Review of the Compassion Measures

The psychometric properties of the included patient-reported compassion measures were compared using the EMPRO, which computes an overall score and subscale scores based on 38 items assessing the evidence regarding various psychometric properties of a measure. Reviewers are provided a list of aspects to consider for each item, before assigning a score on a Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” (4) to “strongly disagree” (1), as well as “not applicable” or “no information available” [59]. The conceptual and measurement model (seven items) portion of the EMPRO is described as the rational and description of the concept of interest, the populations it is aimed to assess, and the relationships between these conceptions. The cultural and language adaptations or translations (two items) portion refers to cultural or linguistic adaptations of the instrument. Reliability (eight items) is operationalized as the degree to which the assessed measure is free from random error, querying about concepts such as internal consistency. Validity (six items) refers to the degree to which the measure measures what it claims to measure, tapping into content, construct, and criterion-related types of validity. Responsiveness (three items) relates to the measure’s ability to detect change in the phenomenon of interest over time. Interpretability (three items) is the degree to which a reader can understand the meaning of the measure’s quantitative scores. Burden (seven items) relates to the demand, such as time and effort, which is imposed on the administrator of the measure, as well as the burden that is placed on the respondent of the measure. Alternative modes of administration (two items) refers to any mode of administration that differs from that which the measure was originally designed for (e.g., self-report versus interviewer administrated).

The EMPRO’s category specific scores are calculated using the mean response of applicable items, when at least 50% of the items are rated. Any items that were responded to with “no information available” are assigned the worst possible score (1 out of 4). Sub-scores for reliability are divided into two sub-sections, internal consistency and reproducibility; the highest of those sub-sections is chosen for the reliability score. The overall score is obtained by calculating the mean of the conceptual and measurement model, reliability, validity, responsiveness, and interpretability scores. An overall score is only produced when at least three of these categories have a score. The scores are then linearly transformed into a range from 0 (worst score) to 100 (best score) [59].

To mitigate bias, each of the patient-reported measures were independently evaluated by two raters (EB, SaS), who were not a part of the review team. Both raters had no previous knowledge, experience, or awareness of the Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire (SCQ) and did not attend any meetings related to its conceptualization, creation, or analysis. To further mitigate bias, the names and any identifying information for two authors (HB, CM) were removed from the SCQ manuscripts as these SCQ authors and EMPRO raters were part of the same faculty, which could unduly influence scoring. Other members of the review team were unknown to the EMPRO raters. To standardize scoring, each rater received training by a member of the review team (HB) on the EMPRO before completing the first round of EMPRO scoring. The first round of scoring found a very high level of inter-rater agreement [69] between independent raters, with a weighted kappa score of 0.82 [70]. Differences between the scores were reviewed and discussed by the two raters until full consensus was reached, as per EMPRO instructions.

Results

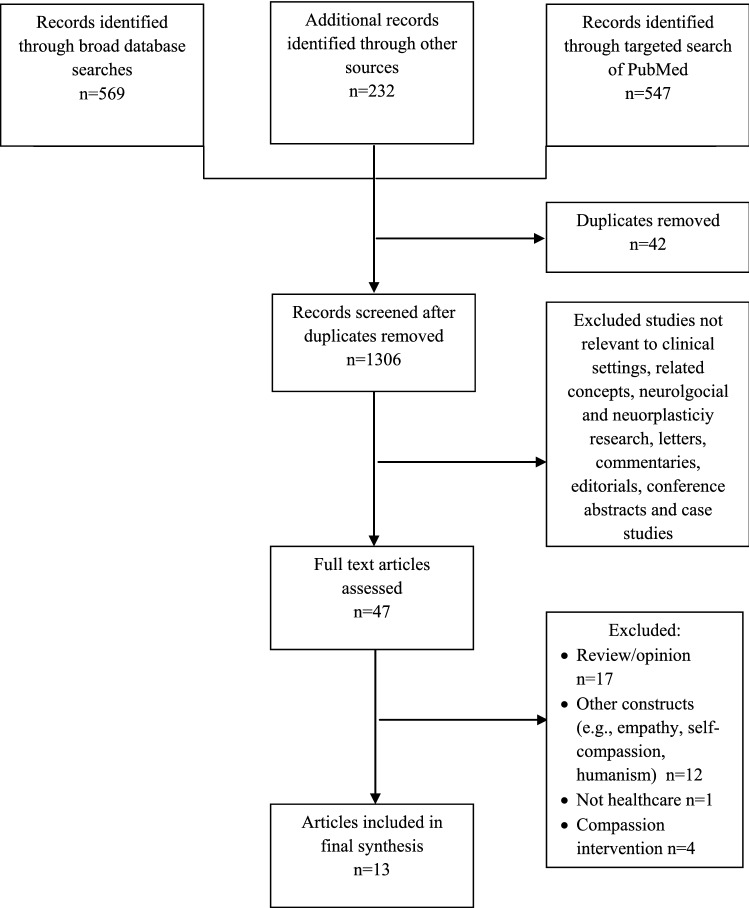

The searches identified 1348 articles published between January 2013 and May 2021. Titles and abstracts were screened, and 47 articles were considered potentially eligible for inclusion. After analyzing the full texts, 34 articles were excluded. Finally, four articles describing additional testing that had been conducted on three compassion measures published before 2016 and nine articles describing four new compassion measures published after 2016 were eligible for inclusion in this review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy

Characteristics of Included Studies

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Measures that underwent additional testing since our original review included the Compassion Competence Scale (CCS) [46, 71], the Compassionate Care Assessment Tool (CCAT)© [47, 72], and the Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale (SCCCS)™ [48, 49, 73]. New compassion measures included the Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others Scale (SOCS-O), a self-report measure of compassion for others [50]; the Bolton Compassion Strengths Indicators (BSCI), a self-report measure of the characteristics (strengths) associated with a compassionate nurse [51]; a five-item Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion (TMPACC) [52–54]; and the SCQ, a 15-item patient-reported compassion measure developed for use in research and clinical practice [55–58].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included measures

| First author, year | Instrument | Description | Items in final instrument | Subscales |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare provider-reported instruments | ||||

| Lee (2016) [71] | CCS | Self-report measure compassion competence in nurses in Korea | 17 |

Communication Sensitivity Insight |

| Alabdulaziz (2020) [46] | CCS-A | Arabic version of the CCS for use in nursing students | 17 |

Communication Sensitivity Insight |

| Gu (2019) [50] | SOSC-O | Self-report measure of compassion for others | 20 |

Recognizing suffering Understanding the universality of suffering Feeling for the person suffering Tolerating uncomfortable feelings Motivation to act/acting to alleviate suffering |

| Durkin (2020) [51] | BSCI | Self-report measure of eight characteristics (strengths) associated with a compassionate nurse | 48 |

Self-care Character Empathy Connection Interpersonal Engagement Competence Communication |

| Patient-reported instruments | ||||

| Burnell (2013) [72] | CCAT© | Patient report measure of the characteristics thought to comprise compassionate care from the patient’s perspective. | 28 |

Meaningful connection Patient expectations Caring attributes Capable practitioner |

| Grimani (2017) [47] | CCAT© | A Greek version of the CCAT© | 20 |

Meaningful connection Patient expectations Caring attributes Capable practitioner |

| Lown (2015) [73] | SCCCS™ | Patient report measure of treating physicians’ compassionate care in a recent hospitalization | 12 | NR |

| Lown (2017) [48] | SCCCS™: In recently hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients in Ireland | Extend the use of the SCCCS™ to people in Ireland | 12 | NR |

| Rodriguez (2019) [49] | SCCCS™ | Review the content validity of the items of the SCCCS™ and estimate the other psychometric properties of the SCCCS™ using classical test and modern test theory methods (Rasch measurement theory) | 12 | NR |

| Roberts (2019) [52] | TMPACC | Patient report measure of clinician compassion on a large scale | 5 | NR |

| Sabapathi (2019) [53] | TMPACC in the emergency department | Assess the validity and reliability of the 5-item tool to measure patient assessment of clinician compassion in the emergency department | 5 | NR |

| Roberts (2021) [54] | TMPACC from physicians and nurses in an inpatient setting | Validate two 5-item tools as measures of the patient experience of physician and nurse compassion for use in the inpatient hospital setting | Two 5-item tools | NR |

| Sinclair (2018, 2020, 2021) [55–58] | SCQ | Patient-reported measure of compassion for patients living with an incurable, life-limiting illness |

15 5-item short form |

NR |

BCSI Bolton Compassion Strengths Indicators, CCAT Compassionate Care Assessment Tool, CCS Compassion Competence Scale, SCCCS Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale, SCQ Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire, SOCS-O Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others Scale, TMPACC Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion, NR Not Reported

Table 2.

Measurement information as reported in the original articles

| First author, year | Instrument | Aspects of construct validity | Reliability | Interpretability | Floor–ceiling effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face validity | Content validity | Factor analysis | Convergent validity | Cronbach’s αa | Test–retest | ||||

| Healthcare provider-reported instruments | |||||||||

| Lee (2016) [71] | CCS | Nurses | 10 experts: 18 items with a content validity index > 80% | 3 factors: communication (8 items), sensitivity (5 items), and insight (4 items). Cumulative variance explained by the 3 factors: 55.94% |

ECS (p < 0.01) CLS (p < 0.01) IRI (p < 0.01) |

Instrument: 0.91 Communication: 0.88 Sensitivity: 0.77 Insight: 0.73 |

0.80 (p < 0.001) | NR | NR |

| Alabdulaziz (2020)a [46] | CCS-A | Panel of 5 experts who assessed the cultural and linguistic equivalence of the scale’s items | Panel of 5 experts: I-CVI = 1; S-CVI/Ave = 1; ITC: = 0.30–0.57 | EFA suggested a 3-factor solution | NR |

Instrument: 0.806 Communication: 0.797 Sensitivity: 0.788 Insight: 0.739 |

ICC = 0.84 | Female students reported higher levels of compassion competence than male students (p < 0.001) | NR |

| Gu (2019)b [50] | SOCS-O |

15 experts in contemplative approaches 15 nonexperts |

22 experts in contemplative approaches 5 researchers |

CFA: Poor fit of a 1-factor model to the data (CFI = 0.72; RMSEA = 0.12, NNFI = 0.69, SRMR = 0.09, AIC = 42176.73) Good fit of 5-factor (CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04, NNFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.03, AIC = 38170.03) and 5-factor hierarchical models (CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04, NNFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.03, AIC = 38174.74) |

SCBCS (p < 0.001) Empathic concern and perspective taking subscales of the IRI (p < 0.001) |

Total scale: 0.94 Recognizing suffering: 0.89 Understanding the universality of suffering: 0.92 Feeling for the person suffering: 0.80 Tolerating uncomfortable feelings: 0.74 Motivation to act/acting to alleviate suffering: 0.91 |

NR | Lower scores for no meditation experience compared to 1–5 (p = 0.001) and > 5 years’ experience (p = 0.006) |

1.6% received the highest possible score (100) 0.1% of the sample received the lowest possible score (20) |

| Durkin (2020) [51] | BCSI | NR | Team of psychology and nursing experts independently analyzed the items |

CFA: Poor fit of a unidimensional model (χ2/df < 4, TLI = 0.79, CFI = 0.81, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% [CI 0.04–0.05], SRMR = 0.06) CFA on each of the compassion strength indicators revealed 8 individual indicators of compassion strengths that were theoretically and statistically valid |

Compassion Satisfaction subscale of the ProQOL (p < 0.001) TEQ (p < 0.001) sWEMWBS (p < 0.001) |

Total compassion strengths: 0.85 Self-care: 0.67 Character: 0.68 Empathy: 0.78 Connection: 0.74 Interpersonal: 0.78 Engagement: 0.64 Competence: 0.80 Communication: 0.55 |

Total compassion strengths: 0.86 Self-care: 0.87 Character: 0.81 Empathy: 0.78 Connection: 0.54 Interpersonal: 0.67 Engagement: 0.79 Competence: 0.60 Communication: 0.66 |

NR | NR |

| Patient-reported instruments | |||||||||

| Burnell (2013) [72] | CCAT© | 25 direct care nurses and 5 patients | 3 members of the hospitals recognition committee | 4 subscales, significantly correlated with each other (p > 0.001); inter-scale coefficients of “moderate/low associations” | NR |

Meaningful connection: 0.87 Patient expectations: 0.80 Caring attributes: 0.77 Capable practitioner: 0.78 |

NR | Women scored significantly higher than men on items related to spiritual beliefs (p < 0.01) and facilitating spiritual support (p < 0.05) | NR |

| Grimani (2017)c [47] | CCAT©: Greek version | 123 patients hospitalized in public hospitals in Athens | NR |

EFA suggested a 3-factor solution CFA showed the model is satisfactory (CFI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.08) |

NR |

Tool: 0.94 Meaningful connection: 0.82 Patient expectations: 0.88 Caring attributes: 0.89 Capable practitioner: 0.87 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Lown (2015)d [73] | SCCCS™ | 20-member committee at the Schwartz Centre for Compassionate Healthcare; patient, physician, and nurse focus groups | 20 member committee at the Schwartz Centre for Compassionate Healthcare; patient, physician, and nurse focus groups |

Factor loading: Importance of compassionate care: ≥ 0.41 Demonstration of compassionate care: ≥ 0.69 |

Overall patient satisfaction/communication/overall support/number of doctors in charge of medical care in hospital |

Importance of compassionate care: ≥ 0.76 Rate a physician’s behavior: ≥ 0.95 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Lown (2017) [48] | SCCCS™: in recently hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients in Ireland | NR | NR | The scale is measuring one factor | NR | Ranged from 0.95 to 0.98 | NR | Patients with better continuity of care and frequency of contact (p < 0.003), pain management, p < 0.01), and who received an apology for a mistake (p = 0.04) score the SCCCS™ significantly higher | 13–31% of participants gave the highest endorsement for all items |

| Rodriguez (2019)e [49] | SCCCS™ | NR | NR |

RMR = 0.03 CFI = 0.92 RMT: item residual 0.13 ± 1.13 and person residual -0.53 ± 1.76 |

CARE (p < 0.0001) | 0.98 | r = 0.90 | NR | Ceiling effect could have been present for some questions. No floor effects |

| Roberts (2019)f [52] | TMPACC | 4 experts in the field of compassionate patient care | 4 experts in the field of compassionate patient care |

CFI = 0.98 TLI = 0.95 SRMR = 0.02 |

Moderate correlation with clinician communication (ρ = 0.44; p < 0.001) and overall patient satisfaction (ρ = 0.52; p < 0.001). A 2-factor model (5-item compassion measure and CG-CAHPS communication questions) had good fit | 0.90–0.94 | NR | NR | NR |

| Sabapathi (2019)e [53] | TMPACC in the emergency department | NR | NR |

CFI = 0.99–1 TLI = 0.99–1 SRMR = 0.01–0.03 |

Moderate correlation with overall patient satisfaction (r = 0.66; 95% CI 0.62–0.69) and recommendation of the ED to friends and family (r = 0.57; 95% CI 0.52–0.61). A 2-factor model (5-item compassion measure and CG-CAHPS overall patient satisfaction question) had good fit | 0.89–0.95 | NR | NR | NR |

| Roberts (2021) [54] | TMPACC from physicians and nurses in an inpatient setting | NR | NR | CFA found all 5 items loaded well on separate single constructs for both the physician and the nurse measures. A 2-factor model (physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures loading on separate latent variables) to have a better fit compared to the single factor model (both the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures loading on a single latent variable) showing the physician and nurse compassion measures are measuring discrete constructs | Physician 5-item compassion measure had a moderate association with the HCAHPS physician communication and overall hospital rating, r = 0.69 (p < 0.001) and r = 0.55 (p < 0.001). Physician 5-item compassion measure had a moderate association with the nursing 5-item compassion measure and the HCAHPS nursing communication and overall hospital rating, r = 0.69 (p < 0.001) and r = 0.62 (p < 0.001) |

Physician compassion measure: 0.96 Nursing compassion measure: 0.95 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Sinclair (2018, 2020, 2021) [55–58] | SCQ | Two rounds of a modified Delphi technique with 14 international subject-matter experts and a patient advisory group (n = 9 patients), and cognitive interviews with patients (n = 16 patients) | Two rounds of a modified Delphi technique with 13 international subject matter experts and a patient advisory group (n = 20 patients), and cognitive interviews with patients | EFA yielded a single factor. CFA revealed strong standardized factor loadings ranging between 0.75 and 0.86, | Significant positive correlations between the SCQ and the SCCCS™ (p < 0.001). Moderately high positive correlations between the SCQ and the PICKER Patient Experience Questionnaire (p < 0.001) | 0.96 | NR | Compassion scores were influenced by age and care location | NR |

AIC Akaike information criterion, BCSI Bolton Compassion Strengths Indicators, CARE Consultation and Relational Empathy Scale, CCAT Compassionate Care Assessment Tool, CCS Compassion Competence Scale, CFA confirmatory factor analysis, CFI comparative fit index, CG-CAHPS Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey, CI confidence interval, CLS Compassionate Love Scale, ECS Emotional Competence Scale, EFA exploratory factor analysis, HCAHPS Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System, ICC intra-class coefficient, I-CVI content validity of items, IRI Interpersonal Reactivity Index, ITC item-total correlation, NNFI nonnormed fit index, NR not reported, ProQOL Professional Quality of Life Scale, RMR root mean square residual, RMSEA root mean square error of approximation, RMT Rasch measurement theory, SCBCS Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale, SCCCS Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale, SCQ Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire, S-CVI/Ave averaging technique for content validity of items, SOCS-O Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others Scale, SRMR standardized root mean squared residual, sWEMWBS Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale, TEQ Toronto Empathy Questionnaire, TLI Tucker-Lewis Index, TMPACC Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion, ED Emergency Department

aAccepted value was 1 or ≥ 0.9 for the I-CVI or S-CVI/Ave; ITC ≥ 0.30 or < 0.80. Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.70 and ICC ≤ 0.80 indicate good internal consistency and test–retest reliability

bFive-factor hierarchical refers to a model in which all 5 factors load on an overarching compassion factor. Both liberal and conservative cutoff points were used for acceptable fit for the CFI, RMSEA, NNFI, and SRMR: CFI and NNFI ≥ 0.90 (liberal) or 0.95 (conservative), RMSEA ≤ 0.10 (liberal) or ≤ 0.06 (conservative), and SRMR > 0.10 (liberal) or 0.05 (conservative). The AIC was used to compare the fit of the models, with lower values indicating superior fit. Cronbach’s α and omega total coefficients values ≥ 0.70 indicate good internal consistency

cRMSEA: recommended critical limit of 0.08

dIncludes estimates for some items that were not retained in the final 12-item version of the measure

eRMR: 0.08 or less considered acceptable for model fit; Bentler Comparative Fit Index: 0.9 or more considered acceptable for model fit; RMT: a perfect fit would be indicated by a summary mean of zero and standard deviation of ± 1

fModel was defined as having good fit if CFI > 0.95, TLI > 0.95, and SRMR < 0.08

Healthcare Provider-Reported Compassion Measures

The Compassion Competence Scale (CCS) The CCS was developed to measure compassion competence among practicing nurses [71]. Scale items measure behaviors that cause patients to perceive their nurses as compassionate. Nurses complete the scale indicating how each item applies to themselves using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree).

Items were designed to measure three dimensions of compassion competence: communication, sensitivity, and insight. A total of 49 items were generated based on a literature review and interviews with nurses that engendered the following definition of compassion competence: “nurses who have respect for and can empathize with patients based on their professional nursing knowledge; nurses who can connect and communicate with patients emotionally and with sensitivity and insight, based on their experience and knowledge; nurses who put constant effort into self-development” ([71], p. 5). The item pool was reduced to 18 following evaluations of content validity and face validity. The psychometric properties of the 18-item scale were examined using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), which excluded one item and extracted three factors: communication, sensitivity, and insight. Evidence of convergent validity was provided by significant correlations between the CCS and the Emotional Competence Scale [74], Compassionate Love Scale [75], and Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) [76] (all, p < 0.01). Internal consistency reliability for the total CCS scale and subscale items were calculated as Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.73 to 0.91. The test–retest reliability coefficient for the total CCS scale was 0.80 (p < 0.001).

An Arabic version of the CCS for use in nursing students was developed using forward and backward translation. The reliability and validity of the CCS were investigated in 317 nursing students in Saudi Arabia. EFA suggested a three-factor solution, Cronbach’s α for the total CCS scale and subscale items ranged from 0.73 to 0.80, and the test–retest reliability coefficient for the total CCS scale was 0.84 [46].

The Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others Scale (SOCS-O) The SOCS-O was developed as a valid and reliable measure of compassion for others. Several stages of scale development and validation were performed in healthcare staff. Healthcare providers complete the scale indicating how true each statement is of them using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (always true) [50].

Items were designed to measure five elements of compassion captured under the following definition: compassion is a “cognitive, affective, and behavioral process consisting of: (a) recognizing suffering; (b) understanding the universality of suffering in human experience; (c) feeling for the person suffering and emotionally connecting with their distress; (d) tolerating any uncomfortable feelings aroused in response to the suffering (e.g., fear, disgust, distress) so that we remain accepting of and open to the person suffering; and (e) acting or being motivated to act to alleviate the suffering” [50], p. 4 [43]. A total of 155 items were generated following interviews with 22 English-speaking experts in contemplative approaches. The item pool was reduced to 20 based on the discretion of members of the research team, evaluation of face validity, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The psychometric properties of the 20-item scale were examined using CFA, which showed all fit indices indicated good fit for a five-factor model and a five-factor hierarchical model, where all items loaded on factors from the five-element compassion definition or an overarching compassion factor. Evidence of convergent validity was provided by significant correlations between the SOCS-O and the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale (SCBCS) [77] (p < 0.001) and the SOCS-O and the empathic concern and perspective taking subscales of the IRI [76] (both p < 0.001). None of the relationships between the SOCS-O and other measures correlated highly enough (r ≥ 0.80) to indicate that they were the same construct (e.g., compassion and empathy) or that measures were indistinguishable (e.g., SOCS-O and existing compassion scales), providing evidence of divergent validity. Internal consistency reliability for the total SOCS-O scale and subscale items were calculated as omega total coefficients (estimated using standardized item loadings from five-factor hierarchical models) and Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.76 to 0.97 and 0.74 to 0.94, respectively.

The Bolton Compassion Strengths Indicators (BSCI) The BSCI comprises a set of measurable indicators of nursing students’ compassion. Nursing students complete the measure indicating how true each statement is of them using a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (definitely not like me) to 6 (definitely like me) [51].

Items were designed to measure eight characteristics (strengths) associated with a compassionate nurse: self-care, character, empathy, connection, interpersonal, engagement, competence, and communication [78, 79]. A total of 340 items were generated based on an a priori Compassion Strengths Model and from preexisting measures of resilience [80], self-compassion [81], the meaning of work [82], compassion satisfaction [83], human connection [84], and nurses’ competence [85]. The item pool was reduced to 48 following evaluations of content validity, endorsement rates and item discrimination, and CFA. The psychometric properties of the 48-item scale were examined using CFA, which supported the a priori eight-factor Compassion Strengths Model. Evidence of convergent validity was provided by significant correlations between the BSCI and the Compassion Satisfaction subscale of the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) [83], the Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) [86], and the Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (sWEMWBS) [87] (all p < 0.001), but not to the extent of overlap and redundancy. Internal consistency reliability for the total BSCI scale and subscale items were calculated as Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.55 to 0.85. The test–retest reliability coefficient for the total BSCI scale and subscale items ranged from 0.54 to 0.87.

Patient-Reported Compassion Measures

The Compassionate Care Assessment Tool (CCAT)© The CCAT© was developed to measure nursing behaviors and actions that are considered compassionate in an acute hospital setting. The tool combines the constructs of compassion and caring and seeks to identify, observe, and measure the relationship between patients’ spiritual needs, including compassion, and nurses’ caring behavior. The tool was designed based on a dictionary definition of compassion: “a sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress with a desire to alleviate it” [72], p. 181, which was broadened to include a spiritual context, as major world religions consider compassion central to their practices and traditions. Caring was defined as “feeling and exhibiting concern and empathy for others,” according to WordNet, 2010 [72], p. 181.

The CCAT© was derived from items within the Spiritual Needs Survey [88] and the Caring Behaviors Inventory (CBI) [89]. The Spiritual Needs Survey asks patients to identify a spiritual need they experienced during a present hospitalization in any of 28 areas, including compassion, and to rate the importance of that need on a scale from slightly to extremely important [88]. The CBI asks patients to rate their nurse’s caring process on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to always [89].

A 40-item tool was generated during a pilot study conducted in 110 hospitalized patients in the USA, in which patients were asked to complete both the Spiritual Needs Survey and the CBI. The initial tool incorporated the ten highest scoring items from the Spiritual Needs Survey and the CBI, the ten items that were most highly correlated to the compassion and kindness statement in the Spiritual Needs Survey (rs = 0.45–0.66), and the ten items that were most highly correlated to the question asking patients to rate the concern nurses demonstrated to them in the CBI (rs = 0.60–0.76). Duplicate items were removed, and 28 items highly rated (statistic not reported) by patients and with strong correlations to the constructs of compassion and caring emerged. Content validity of the final CCAT© was examined by three members of the hospital’s recognition committee, which is responsible for presenting the DAISY® Award for Extraordinary Nurses, an honor that is awarded based on several criteria, including compassionate care. Face validity was assessed by 25 direct care nurses and five patients.

The psychometric properties of the 28-item CCAT© were examined in 250 patients in a hospital setting. Compassionate care was pre-defined for each patient as “understanding suffering and wanting to do something about it.” Patients were asked to rate the personal importance of each CCAT© item on a scale of 1 (not important) to 4 (extremely important). Principal component factor analysis showed 20 items merged into four subscales, including meaningful connection (eight items), patient expectations (five items), caring attributes (four items), and capable practitioner (three items). All scales were significantly correlated with each other (p < 0.001), but the inter-scale coefficients were moderate or low, indicating that each subscale measured distinct characteristics. Internal consistency reliability of the meaningful connection, patient expectations, caring attributes, and capable practitioner subscales were calculated as a Cronbach’s α of 0.87, 0.80, 0.77, and 0.78, respectively.

A Greek version of the 28-item CCAT© was developed using forward and backward translation. The reliability and validity of the tool were investigated in 123 patients hospitalized in public hospitals in Athens. EFA and CFA suggested a three-factor solution, inter-scale coefficients demonstrated strong associations between subscales (r = 0.65–0.78), and Cronbach’s α was 0.94 for the tool and 0.82, 0.88, 0.89, and 0.87 for the meaningful connection, patient expectations, caring attributes, and capable practitioner subscales, respectively [47].

The Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale (SCCCS)™ The SCCCS™ was developed to measure patient perceptions of the compassionate care provided by their treating physician during a recent hospitalization [73]. Non-hospitalized patients are asked to rate the importance they attribute to 12 interpersonal behaviors in the provision of compassionate healthcare on a scale of 1 (lowest possible rating) to 10 (highest possible rating). Hospitalized/recently hospitalized patients are asked to rate the successful demonstration of these behaviors.

The scale was designed using 16 items identified by a committee (20 cancer survivors, individuals suffering from chronic pain and/or debilitating illnesses, family members of patients, and individuals working in healthcare policy and advocacy) created to evaluate compassionate care provided by physicians and other caregivers nominated for a compassionate care award [24]. The items were vetted through focus groups (patient, nurse, physician) and incorporated into surveys of recently hospitalized patients in the USA [24]. During psychometric analysis, four items with the lowest item-total correlations were omitted to generate a 12-item scale.

The psychometric properties of the 12-item scale were recently examined in 501 recently hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients in Ireland [48] and 167 patients recruited from an online patient community (PatientsLikeMe, Inc.) in the USA [49]. Results from the sample in Ireland showed that the scale measured one factor and had good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.95 to 0.98) [48]. Results from the sample in the USA confirmed the one-factor solution [49]. Some fit statistics (root mean square residual [RMR] = 0.03, CFI = 0.92) were indicative of good model fit. Convergent validity was reported based on a positive correlation between the SCCCS™ and the Consultation and Relational Empathy Scale (CARE) (p < 0.0001) [90]. Internal consistency reliability was calculated as a Cronbach’s α of 0.98. Test–retest reliability was calculated as r = 0.90. Floor effects were reportedly not present for any scale items, but a ceiling effect was present for some. Rasch measurement theory (RMT) confirmed the unidimensionality of the scale and was used to evaluate the scaling properties and construct validity of the SCCCS™. Fit was improved by rescoring three items, after which most RMT analyses showed satisfactory psychometric properties.

The Five-item Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion (TMPACC) A 5-item scale was developed to measure patient assessment of clinician compassion. Patients complete the five-item TMPACC indicating their perceptions of their clinician’s compassion on a 4-point frequency scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The measure was intended and designed to be a subscale within the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey, which is used by the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to survey patient satisfaction with visits to the adult clinics of healthcare organizations that receive payments from Medicare [52].

A pool of 12 items for potential inclusion in the TMPACC was generated according to a theoretical understanding of the construct of compassion that was derived from a review of the published healthcare literature [13]. Based on the findings, the authors defined compassion as “an emotional response to another’s pain and suffering involving an authentic desire to help” [52], p. 3.

Construct and face validity of the 12 items were assessed by a panel of four experts in the field of compassionate patient care, working together in the same institutions, including one study author. Items were further reviewed by two patient experience analysts, and members of the research team from Press Ganey Associates, which administers and reports CG-CAHPS surveys in partnership with most US hospitals.

The 12-item scale was incorporated into the CG-CAHPS survey and pilot tested for a 30-day period. A total of 21,732 surveys were distributed, 3031 completed responses were received, and 313 different clinicians across > 15 specialties were assessed. EFA showed the 12 items loaded well on a single construct (values > 0.65), with the five items with the strongest factor loadings on a single construct being selected. The Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion of the 12-item and five-item scales were compared to generate a concise scale that could be easily combined with the CG-CAHPS.

The final five-item scale was incorporated into the CG-CAHPS survey and pilot tested for a second 30-day period. A total of 23,066 surveys were distributed, 3462 completed responses were received, and 312 different clinicians were assessed. Validity and reliability of the final five-item scale were examined. CFA showed the items loaded well on a single construct (standardized coefficients > 0.80) and the model had good fit (CFI = 0.98; Tucker-Lewis Index [TLI] = 0.95, standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR] = 0.02; χ2 test for model fit was significant). The five-item scale had a moderate to moderately strong correlation with the CG-CAHPS physician communication (rs = 0.44, p < 0.001) and overall patient satisfaction (rs = 0.52; p < 0.001) items. CFA showed the five-item compassion scale and CG-CAHPS communication questions loaded on separate latent variables (CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.04), suggesting the compassion scale was not redundant. Internal consistency reliability was calculated as a Cronbach’s α of 0.94 for the entire validation cohort and > 0.90 across specialties.

The five-item scale was psychometrically validated for CG-CAHPS use in the ED (Emergency Department) setting among 866 patients across three academic EDs in the USA [53]. CFA found all items loaded well on a single construct, and the model had good fit (CFI = 1; TLI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.02; χ2 test for model fit p = 0.042). The five-item scale had a moderately strong correlation with the CG-CAHPS recommendation of the ED to friends and family (r = 0.57) and overall patient satisfaction (r = 0.66) items. CFA showed the five-item compassion scale and CG-CAHPS overall patient satisfaction question loaded on separate latent variables (CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.04), suggesting the compassion scale was not redundant. Internal consistency reliability was calculated as a Cronbach’s α of 0.93 for the entire validation cohort and > 0.93 across academic institutions.

The five-item scale was validated as a measure of patient assessment of physician and nurse compassion in the inpatient setting [54]. Each of the five items were modified to elicit responses that were relevant to compassion from physicians or compassion from nurses. CFA indicated that these adapted scales loaded on separate latent factors. Physician compassion was strongly correlated with physician communication (r = 0.69), and was moderately strongly correlated with overall hospital rating (r = 0.55). Similarly, nurse compassion was strongly associated with nurse communication (r = 0.69), and strongly correlated to overall hospital rating (r = 0.62). Each of the healthcare provider’s communication ratings partially mediated their respective relationships between that specific healthcare provider’s compassion and overall hospital rating.

The Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire (SCQ) The SCQ was developed as a patient-reported measure of compassion. Patients are asked to rate their experience of compassion from their healthcare providers using a 5-point Likert scale of agreement (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree) [55–58].

Design of the SCQ was informed by the Patient Compassion Model [1], an empirical model of compassion derived directly from patient interviews that demarcates compassion from sympathy and empathy, delineates domains of compassion and their relationship with one another, and is transferable across care settings and patient populations [55]. The validity and clinical utility of the Patient Compassion Model has also been validated among healthcare providers [91].

After determining the scope and purpose of the measure, 109 items were generated using a table of specifications to ensure content coverage across the domains of the Patient Compassion Model [56, 57]. Content validity (items, question stems, response scale) of the draft 109-item SCQ was established using two rounds of a modified Delphi technique with 14 international subject matter experts and a patient advisory group (nine patients recruited from established patient advisory groups who had been vetted by the Alberta Cancer Foundation, Patient Partnerships, and the Alberta Innovates, Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research SUPPORT Unit), and cognitive interviews with 16 patients. A total of 55 items were removed due to low content validity index (< 80%) or because they were the lower-performing item amongst two alternatively worded items [56, 57].

The psychometric properties of the SCQ were then examined in 303 patients at the EFA stage and 330 patients at the CFA stage across four care settings (acute care, hospice, long-term care, home care) [58]. The 54-item scale was revised to 49 items based on the test–retest reliability results, as five items achieved an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) below < 0.70. EFA of the remaining 49 items using principal axis factoring (PAF) resulted in the removal of a further 11 items, with the remaining 38 items yielding a single factor [58].

The optimal number of items in the measure was determined as 15 based on factor loadings, internal reliability, and qualitative domain coverage. CFA of the 15-item scale revealed strong standardized factor loadings ranging between 0.75 and 0.86. Global fit was further improved by adding covariances to the model. Item response theory analyses indicated that the SCQ precisely measures compassion across the wide range of patient experiences with their healthcare providers. The average marginal reliability of the SCQ was 0.85. Convergent validity was shown by a significant and strong positive correlation between the SCQ and the SCCCS™ [64] (r = 0.75, p < 0.001), while divergent validity was shown by moderately strong positive correlations (r = 0.60) between the SCQ and the PICKER Patient Experience Questionnaire [92]. The SCQ was also weakly and negatively associated with depression (r = −0.13), and poor wellbeing (r = −0.17), and not significantly associated with other symptoms, as measured by the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS-r) symptom [93] (p < 0.001). These findings indicate that the SCQ is related to but distinct from patient satisfaction and symptom distress. Interpretability was supported as compassion scores were influenced by age and care location. Internal consistency reliability was calculated as a Cronbach’s α of 0.96.

A five-item short-form version (SCQ-SF) of the measure was developed from the highest loading items on each of the five theoretical domains of the Patient Compassion Model [58]. A French adaption of the SCQ (QCS) is also available, with a Spanish adaption study currently being conducted.

Comparative Review of Patient-Reported Compassion Measures

EMPRO overall and subscale scores for the four patient-reported instruments included in this review are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

EMPRO scores

| EMPRO attribute | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | I. Conceptual and measurement model | II. Cultural and language adaptations | IIIa. Internal consistency | IIIb. Reproducibility | III. Reliability | IV. Validity | V. Responsiveness | VI. Interpretability | VIIa. Respondent burden | VIIb. Administrative burden | VIII. Alternative modes of administration | Overall weighted EMPRO scores |

| SCQ | 90.48 | – | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 0* | 0* | 100 | 50 | 0* | 58.1 |

| SCCCS™ | 80.95 | – | 75 | 41.67 | 75 | 93.33 | 0* | 0* | 44.44 | 0* | 0* | 49.86 |

| TMPACC | 71.43 | – | 66.67 | 0* | 66.67 | 60 | 0* | 0* | 66.67 | 25 | 0* | 40.67 |

| CCAT© | 61.9 | 44.44 | 25 | 0* | 25 | 44.44 | 0* | 0* | 11.11 | 25 | 0* | 26.27 |

Notes on scoring The attribute-specific scores are obtained by calculating the mean response of the applicable items when at least 50% of the items are rated. Items for which the “no information” response option has been selected are assigned a score of 1 (lowest possible score). Afterwards, the scores are linearly transformed to a range of 0 (worst possible score) to 100 (best possible score). Separate sub-scores for the “reliability” attribute can be calculated as this attribute is formed by 2 components, internal consistency and reproducibility. The highest sub-score is then chosen for the “reliability” score. In addition to the attribute-specific scores, an overall score is obtained by calculating the mean of the 5 metric-related attributes: “conceptual and measurement model,” “reliability,” “validity,” “responsiveness,” and “interpretability”. The overall score is only calculated when at least 3 of these 5 attributes have a score. EMPRO scores are considered reasonably acceptable if they reach at least 50 points (half the maximum score)

CCAT Compassionate Care Assessment Tool, EMPRO Evaluating Measures of Patient-Reported Outcomes, SCCCS Schwartz Center Compassionate Care Scale, SCQ Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire, TMPACC Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion

*No information was available; thus, the score was 0

The SCQ scored the highest for both the EMPRO overall score and ten of the 11 subscales, including the key subscales of conceptual and measurement model, internal consistency, reproducibility, reliability, and validity. Most measures had too much missing data on the EMPRO cultural and language adaptation, responsiveness, interpretability, and alternative modes of administration items to support the calculation of meaningful subscale scores.

Discussion

This study leveraged and extended our previous review of compassion measures in healthcare [42] by incorporating results from additional testing of previously identified compassion measures and evaluating newly developed compassion measures. Our previous review of the literature up to 2016 concluded that no instrument measured compassion in healthcare in a comprehensive or methodologically rigorous fashion—the results of this review suggest this is no longer the case. After reviewing the evidence of three previously identified compassion measures that underwent additional reliability and validity testing and four new compassion measures, the SCQ emerged as the most valid and reliable measure of compassion. As the gold standard compassion measure, the SCQ (1) establishes the empirical foundation for research focused on the development and evaluation of interventions aimed at the enhancement of compassion at the healthcare provider and organizational levels; (2) provides a clinically informed and relevant measure to allow the routine assessment of compassion in clinical practice; and (3) provides healthcare organizations the ability to routinely report, monitor, evaluate, and improve compassion across their organization and at a systems level utilizing an evidence-based tool.

Our updated literature search of compassion measures identified one recently updated healthcare provider-reported compassion measure, two newly published healthcare provider-reported compassion measures, two recently updated patient-reported compassion measures, and two newly published patient-reported compassion measures. The healthcare provider-reported compassion measures were created to assess self-perceived compassion competence in nurses [46, 71], self-perceived compassion for others in many adult populations, including healthcare providers [50], or the self-perceived characteristics (strengths) associated with a compassionate nurse [51]. The patient-reported compassion measures were designed to measure patient perceptions of compassion provided by their healthcare provider [47–49, 52–58, 72, 73]. With the exception of the SCQ, none of the patient-reported compassion measures strictly adhered to measure development guidelines [59, 63, 68], adequately established initial construct validity by first defining the concept of interest, or engaged patients across all stages of development, and each of them, to varying degrees, had limited evidence of validity, reliability, sensitivity, internal consistency, and transferability across diverse patient populations.

These results serve as a reminder that measure development should begin with careful consideration and definition of the construct of interest and should be based on a theoretical model illustrating the relationship between the domains of the construct of interest. Without this imperative step, the generation of candidate items and all subsequent testing, while producing some informative results, ultimately rests on a precarious conceptual foundation. Further, after establishing initial construct validity, measure developers must adequately describe how candidate items are empirically grounded within the construct. Finally, to ensure relevance, a comprehensive measure of compassion in healthcare should not simply be developed according to the opinions of researchers or healthcare providers alone, but the perceptions of patients. Healthcare providers’ perceptions and good intentions are important, but may vary considerably from patients actual experiences.

Failing to establish initial construct validity of a compassion measure resulted in measures that did not recognize the multiple dimensions of compassion, which include virtues, relational communication, seeking to understand, relational space, and attending to needs. This in turn negatively impacts content coverage, item development, validity, and reliability, and produces a measure that assesses compassion in an incomplete fashion [1, 29, 42, 44, 45, 94, 95]. Among the compassion measures identified in this review, only the SCQ established construct validity in a rigorous and robust fashion. After an initial comprehensive and critical review of the compassion measure literature in healthcare was conducted [29], a large qualitative study with patients with advanced cancer [1] informed the development of a theoretical Patient Compassion Model that delineated the construct of interest and its associated domains, and their relationship with one another. Next, qualitative interviews with non-cancer patients living with a life-limiting illness verified the transferability of the Patient Compassion Model and ensured that each facet of the model was adequately represented and generalizable to patients with varying life-limiting illnesses [55]. A Table of Specifications (TOS) was then implemented to facilitate item generation and ensure that the items within the measure adequately covered each domain [56].

Conversely, the construct validity of the other compassion measures included in this review was tenuous. One healthcare provider-reported compassion measure (SOCS-O) assessed aspects of compassion consistent with an a priori definition based on a literature search, with compassion being conflated with self-compassion [50], which while focusing on the cultivation of qualities and feelings within the virtues domain of compassion, does not encompass the relational or action domains of compassion [96]. The other (BSCI) [51] was based on an a priori Compassion Strengths Model and from preexisting measures of resilience [80], self-compassion [81], the meaning of work [82], compassion satisfaction [83], human connection [84], and nurses’ competence [85]. Conflation was a common limitation of the patient-reported compassion measures. The CCAT© [72] was developed by combining items selected from measures of spiritual wellbeing and caring. While partially addressing some domains of compassion, including virtues and attending to needs, it does not assess understanding—which is essential in ensuring that subsequent components of compassion such as relational communication and attending to needs are attuned to patient needs and preferences. Notably, the CCAT© includes aspects of empathy or sympathy in its definition of compassion [72], even though compassion has been demonstrated to be a separate construct with unique motivators and outcomes [1, 29, 97]. Items for the SCCCS™ were generated by a committee adjudicating on a compassionate care award. While many of the items cover a number of the domains of compassion reported in the literature [73], they do not account for compassion’s virtue-based motivators and its predication in action [1, 98]. Similarly, the TMPACC was based on a definition of compassion derived from a literature search rather than qualitative research or a systematic process of determining construct validity, resulting in compassion being described as an “emotional response,” with limited details on the nature of this emotional response [52]. Finally, four of the five items in the TMPACC closely resemble the SCCCS™, and the SCCCS™ and TMPACC use the term “compassion” within the wording of their items instead of providing an adjective describing a variable that facilitates patients’ assessment of compassion as a construct [52–54, 73].

Patients reside at the epicenter of compassion and their experience of compassion, or lack thereof, is critical to determining the impact of compassion on clinical outcomes and the fidelity of research on the topic—particularly the development of a patient-reported compassion measure. It is therefore imperative that the patient perspective be included across each stage of the development of a compassion measure for use in healthcare research and clinical practice [1, 52]. This is particularly important considering patients increasing perception that compassion is lacking from their healthcare experience and recent evidence suggesting that compassion is the quintessential factor of the patient experience [8]. The SCQ not only incorporated the patient perspective across all study stages, but was directly informed by preliminary patient orientated research and the foreknowledge of existing limitations of other compassion measures [55–58]. The Patient Compassion Model, which forms the basis of the SCQ, is a theoretical model of compassion that was generated directly from patients, who were able to delineate compassion from the constructs of empathy and sympathy, and indicated their strong preference for compassion [1]. The transferability of the Patient Compassion Model was established in other patient populations, and items generated in accordance with strict measure development guidelines [55–59, 63, 68] were validated by both patients and subject matter experts [55–57]. Cognitive interviews were then conducted with patients to assure the readability and understandability of the measure, before undergoing test–retest, EFA, CFA, and item response theory testing [58]. Many of the other measures identified in this review included patients in aspects of the validation phase [52, 72, 73]; however, patients were not included in a sufficiently rigorous fashion in the developmental stage, impacting construct validity and the fidelity of the measure from the outset (Tables 2 and 3) [59].

Psychometric evidence regarding the validity and reliability of the compassion measures included in this review were reported to varying degrees. We applied the EMPRO [59], a validated tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported measures, to evaluate the quality of the patient-reported compassion measures identified by our searches. With the exception of the SCQ, the patient-reported compassion measures in this review had significant validity and reliability issues, and failed to reach the threshold for acceptability as defined by the EMPRO. Although some types of psychometric data are not yet available for the SCQ, as further testing is required to determine the measure’s responsiveness, interpretability, and criterion validity, the EMPRO overall score for the SCQ was 58.1, almost 9 points higher than any other compassion measure, all of which have had the benefit of time to undergo additional testing.

While the EMPRO is a valid and reliable tool for evaluating measures of patient-reported outcomes, it is not without limitations. Specifically, EMPRO overall scores should be interpreted with caution, as they do not clearly represent the variability in the strengths, weaknesses, and applicability of the assessed measures. The EMPRO overall score does not consider the relative importance of each specific measurement property, but weights each subscale item equally. Consequently, overall EMPRO scores do not take into account the foundational necessities of achieving reliability and validity for a measure before evaluating other important measurement properties. When these subscales are evaluated separately, the SCQ psychometric strength is further exemplified, as it achieved full subscale scores for internal consistency, reliability, validity, and respondent burden that were up to 43 points higher than any other compassion measure included in this review.

Findings from this review establish the SCQ as the “gold standard” compassion measure, providing an empirical basis for evaluations of compassion in routine care. Previous reports show that compassion is catalyzed through healthcare providers’ baseline virtues, but modified by the interpersonal and work conditions in the organizations within which healthcare providers practice [99, 100]. As a validated measure of healthcare provider compassion, the SCQ should be applied in clinical practice to identify areas for ongoing improvement in individuals and to aggregate data across practice settings to identify organizational factors affecting the flow of compassion.

This study was associated with several limitations. First, despite a robust search strategy developed by experts in the field of compassion and measurement, relevant studies could have been missed. Second, the search was restricted to publications in the English language, which may have limited the generalizability of this review. Finally, our comparison of the psychometric evidence regarding measurement validity and reliability using the EMPRO was undertaken by researchers at the University of Calgary, where the developers of the SCQ worked. While bias was minimized by utilizing EMPRO scorers who were not part of the research team, expunging the names of authors known to the reviewers from the SCQ manuscripts, and having reviewers first assess each measure independently, bias may nevertheless have been introduced.

Conclusion

This review synthesized the literature related to measures of compassion in healthcare. The objective was to identify compassion measures that were intended for research and/or clinical practice. Our previous review of compassion measures in healthcare between 1985 and 2016 concluded that no single measure available at the time measured compassion in healthcare in a comprehensive or methodologically rigorous fashion. The present review examined additional testing of three previously identified compassion measures and four new compassion measures. Among these, the SCQ emerged as the gold standard compassion measure, providing an empirical basis for evaluations of compassion in routine patient care and research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Funding

The preparation of this review was supported through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Scheme Grant (#148543).

Conflict of interest

Dr. Sinclair has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hack has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Kondejewski has no conflicts of interest. Harrison Boss has no conflicts of interest. Dr. MacInnis has no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data

The data are available in the public domain.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

All authors were involved in study design and overseeing the review process and contributed to the manuscript. In addition to these substantive contributions, Dr. Sinclair conceived, designed, oversaw the review of, and was the primary author of the manuscript. Dr. Kondejewski and Dr. Sinclair conducted the searches and selected eligible studies. Dr Hack provided expert opinion on review content, manuscript development, and scientific direction. Dr. MacInnis provided expert opinion on review content and manuscript development. Harrison Boss provided expert opinion on review content and manuscript development and coordinated and developed a training guide for the EMPRO raters, Sara Salavati (SaS) and Elena Buliga (EB).

References

- 1.Sinclair S, McClement S, Raffin Bouchal S, et al. Compassion in health care: an empirical model. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(2):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Hospice and Palliative Care Association. Definition of Palliative Care. 1995. http://www.chpca.net/. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- 3.American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics: Principle 1. 2001. http://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/principles-of-medical-ethics.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- 4.Canadian Medical Association. Code of Ethics. 2004. http://policybase.cma.ca/dbtw-wpd/PolicyPDF/PD04-06.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- 5.NHS Commissioning Board . Compassion in practice: Nursing, midwifery and care staff–Our vision and strategy. Leeds: NHS Commissioning Board; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Nurses Association. Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses. 2008. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-fr/code-of-ethics-for-registered-nurses.pdf?la=en. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- 7.Institute of Medicine . Improving Medical Education: Enhancing the Behavioral and Social Science Content of Medical School Curricula. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beryl Institute. Consumer Study on Patient Experience. 2018. https://www.theberylinstitute.org/page/PXCONSUMERSTUDY. Accessed 16 Dec 2019.

- 9.Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The quadruple aim: Care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:608–610. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tepper J. The “forgotten” fourth aim of quality improvement in health care—improving experience of providers. CMAJ blogs 2016. Accessed on February 19, 2020 from. https://cmajblogs.com/the-forgotten-fourth-aim-of-quality-improvement-in-health-care-improving-the-experience-of-providers/. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- 12.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, And Cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trzeciak S, Roberts BW, Mazzarelli AJ. Compassionomics: Hypothesis and experimental approach. Med Hypotheses. 2017;107:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trzeciak S, Mazzarelli A. Compassionomics: the revolutionary scientific evidence that caring makes a difference. Pennsacola: Studer Group; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sturgeon D. Measuring compassion in nursing. Nurs Stand. 2008;22(46):42. doi: 10.7748/ns2008.07.22.46.42.c6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson R. Can we mandate compassion? Hastings Cent Rep. 2011;41(2):20–23. doi: 10.1353/hcr.2011.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry. London: The Stationary Office; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadopoulos I, Ali S. Measuring compassion in nurses and other healthcare professionals: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;16(1):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Relationships between physician practice style, patient satisfaction, and attributes of primary care. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(10):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Shannon SE, Rubenfeld GD, Patrick DL, Curtis JR. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doohan I, Saveman BI. Need for compassion in prehospital and emergency care: a qualitative study on bus crash survivors' experiences. Int Emerg Nurs. 2015;23(2):115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross AJ, Anderson JE, Kodate N, Thomas L, Thompson K, Thomas B, Key S, Jensen H, Schiff R, Jaye P. Simulation training for improving the quality of care for older people: An independent evaluation of an innovative programme for interprofessional education. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(6):495–505. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Family Med. 2011;24(3):229–239. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lown BA, Rosen J, Marttila J. An agenda for improving compassionate care: a survey shows about half of patients say such care is missing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1772–1778. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crowther J, Wilson KC, Horton S, Lloyd-Williams M. Compassion in healthcare—lessons from a qualitative study of the end of life care of people with dementia. J R Soc Med. 2013;106(12):492–497. doi: 10.1177/0141076813503593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riggs JS, Woodby LL, Burgio KL, Bailey FA, Williams BR. "Don't get weak in your compassion": bereaved next of kin's suggestions for improving end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):642–648. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youngsen R. Foreward. In: Shea S, Wynyard R, Lioni SC, editors. Compassionate Healthcare: Challenges in Policy and Practice. London, UK: Routledge; 2014, p. xix-xxiii.

- 28.Willis L. Raising the bar: the shape of caring review. London: Health Education England; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinclair S, Norris J, McConnell S, Chochinov HM, Hack TF, Hagen NA, McClement S, Bouchal SR. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15(6):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soto-Rubio A, Sinclair S. In defense of sympathy, in consideration of empathy, and in praise of compassion A History of the Present. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(5):1428–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dewar B, Cook F. Developing compassion through a relationship centred appreciative leadership programme. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(9):1258–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levinson WRD, Mullooly J, Dull V, Frankel R. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy F, Jones S, Edwards M, James J, Mayer A. The impact of nurse education on the caring behaviours of nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(2):254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, Tauschel D, Fischer MR, Wirtz M, Woopen C, Haramati A, Scheffer C. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):996–1009. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernando AT, Consedine NS. Barriers to medical compassion as a function of experience and specialization: psychiatry, pediatrics, internal medicine, surgery, and general practice. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(6):979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maclean R. The vale of Leven Hospital Inquiry. Edinburgh: APS Group Scotland; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nursing and Midwifery Council . The code: professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses and midwives. London: NMC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Department of Health . Confidence in caring: a framework for best practice. London: Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Easter DW, Beach W. Competent patient care is dependent upon attending to empathic opportunities presented during interview sessions. Curr Surg. 2004;61(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, Groll D, Gafni A, Pichora D, Shortt S, Tranmer J, Lazar N, Kutsogiannis J, Lam M, Canadian Researchers End-of-Life Network (CARENET) What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):627–633. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(3):351–374. doi: 10.1037/a0018807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinclair S, Russell LB, Hack TF, Kondejewski J, Sawatzky R. Measuring compassion in healthcare: A comprehensive and critical review. Patient. 2017;10(4):389–405. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss C, Taylor BL, Gu J, Kuyken W, Baer R, Jones F, Cavanagh K. What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;47:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Cingel M. Compassion in care: A qualitative study of older people with a chronic disease and nurses. Nurs Ethics. 2011;18(5):672–685. doi: 10.1177/0969733011403556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bramley L, Matiti M. How does it really feel to be in my shoes? Patients' experiences of compassion within nursing care and their perceptions of developing compassionate nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(19–20):2790–2799. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]