Abstract

Background

Despite the focus on overdose deaths co-involving opioids and benzodiazepines, little is known about the epidemiologic characteristics of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths in the USA.

Objective

To characterize co-involved substances, intentionality, and demographics of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths in the USA from 2000 to 2019.

Design

Cross-sectional study using national mortality records from the National Vital Statistics System.

Subjects

US residents in the 50 states and District of Columbia who died from a benzodiazepine-involved overdose from 2000 to 2019.

Main Measures

Demographic characteristics, intention of overdose, and co-involved substances

Key Results

A total of 118,208 benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths occurred between 2000 and 2019 (median age, 43 [IQR, 32–52]; male, 58.6%; White, 93.3%; Black, 4.9%; American Indian and Alaska Native, 0.9%; Asian American and Pacific Islander, 0.9%; Hispanic origin, 6.4%). Opioids were co-involved in 83.5% of the deaths. Nine percent of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths did not involve opioids, cocaine, other psychostimulants, barbiturates, or alcohol. Overdose deaths were classified as suicides in 8.5% of cases with benzodiazepine and opioid co-involvement and 36.2% of cases with benzodiazepine but not opioid involvement. Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths increased from 0.46 per 100,000 individuals in 2000 to 3.55 per 100,000 individuals in 2017 before decreasing to 2.96 per 100,000 individuals in 2019. Benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality rates increased from 2000 to 2019 among all racial groups, both sexes, and individuals of Hispanic and non-Hispanic origin. Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths decreased among White individuals, but not Black individuals, from 2017 to 2019.

Conclusions

Interventions to reduce benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality should consider the demographics of, co-involved substances in, and presence of suicides among benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths.

INTRODUCTION

Although the co-involvement of benzodiazepines and opioids in overdose deaths has received considerable attention, little is known about epidemiologic characteristics of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths.1–4 This study characterized co-involved substances, intentionality, and demographics of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths in the USA from 2000 to 2019.

METHODS

The Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board determined that this study was not human subject research. Death records for US residents of the 50 states and the District of Columbia were obtained from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS).5 The NVSS collects information from state-level or city-level (Washington D.C. and New York City) reporting systems about all deaths in the USA.6

Overdose deaths were identified based on ICD-10 codes of X40-45 (accidental poisoning), X60-65 (intentional self-poisoning [suicide]), X85 (assault by drugs), or Y10-15 (poisoning with undetermined intent) as underlying cause of death. Involved substances were identified from ICD-10 codes listed as contributing causes of death (Table 1). Any ICD-10 code between T36.0 and T51.9 was considered a specified cause of death, except for T50.9 (other and unspecified substances), which, due to the lack of specificity in its use, was considered separately.

Table 1.

Substance Identification and Classification. Substances Were Identified Based on Corresponding ICD-10 Codes. ICD-10 Definitions for Each Substance Code Are Presented in Brackets

| Substance | ICD-10 code |

|---|---|

| Opioids | |

| Heroin | T40.1 [heroin] |

| Natural and semi-synthetic opioids15 (excluding heroin and opium) | T40.2 [other opioids] |

| Methadone | T40.3 [methadone] |

| Synthetic opioids, excluding methadone15 | T40.4 [other synthetic narcotics] |

| Opium and other and unspecified narcotics | T40.1 [opium], T40.6 [other and unspecified narcotics] |

| Cocaine | T40.5 [cocaine] |

| Antiepileptic and sedative-hypnotic drugs (excluding barbiturates and benzodiazepines) | T42.0 [hydantoin derivatives], T42.1 [iminostilbenes], T42.2 [succinimides and oxazolidinediones], T42.5 [mixed antiepileptics, not elsewhere classified], T42.6 [other antiepileptic and sedative-hypnotic drugs], T42.7 [antiepileptic and sedative-hypnotic drugs, unspecified] |

| Barbiturates | T42.3 [barbiturates] (excludes thiobarbiturates) |

| Benzodiazepines | T42.4 [benzodiazepines] |

| Antidepressants | T43.0 [tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants], T43.1 [monoamine-oxidase-inhibitor antidepressants], T43.2 [other and unspecified antidepressants] |

| Antipsychotic drugs | T43.3 [phenothiazine antipsychotics and neuroleptics], T43.4 [butyrophenone and thioxanthene neuroleptics], T43.5 [other and unspecified antipsychotics and neuroleptics] |

| Psychostimulants (excluding cocaine) | T43.6 [psychostimulants with abuse potential] (excludes cocaine) |

| Other and unspecified substances | T50.9 [other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances] |

| Alcohol | T51.0 [ethanol], T51.9 [unspecified alcohols] |

| Other specified non-opioids | ICD-10 codes between T36.0 and T51.9 that are not listed above |

Demographic information about individuals who died from benzodiazepine-involved overdoses was extracted from NVSS public use files. Before 2018, the NVSS reported a single race (American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Black, or White) for each decedent.7 When a state reported multiple races for a decedent to the NVSS prior to 2018, these were bridged to a single race.5,8 The NVSS started reporting multiple races for decedents starting in 2018 but continued to bridge races of decedents to the previous categories (bridged-race) to allow comparisons.7 This paper follows the bridged-race reporting system to describe trends between 2000 and 2019.

Annual population estimates, including race- and sex-specific population estimates, were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics bridged-race population estimates.8 Intercensal population estimates were obtained from 2000 to 2009, and post-censal (Vintage 2019) estimates were used for 2010 to 2019.8

Benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths during 2000–2019 were descriptively compared across demographic characteristics, overdose types, and co-involved substances. Crude rates for overdose-specific mortality were calculated to analyze trends. Race-, sex-, and Hispanic origin-specific mortality rates were also calculated. Analyses were conducted with R, version 4.04, between November 25, 2020, and May 31, 2021. The report follows Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cross-sectional studies.9

RESULTS

Between 2000 and 2019, 118,208 people died from benzodiazepine-involved overdoses (Table 2). The median age of individuals was 43 (IQR, 32–52) and 69,264 were male (58.6%). Among individuals dying from benzodiazepine-involved overdoses, 110,335 were identified as White (93.3%), 5814 were identified as Black (4.9%), 1053 were identified as American Indian and Alaska Native (0.9%), and 1006 were identified as Asian and Pacific Islander (0.9%). Seven thousand, five hundred twenty-six decedents were identified as Hispanic (6.4%).

Table 2.

Benzodiazepine-Involved Overdose Deaths During 2000–2019 in the USA

|

Total (n= 118,208) |

Co-involving opioids (n= 98,746) | Not involving opioids (n= 19,462) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin (n = 16,847) |

Synthetic opioids‡ (n = 27,706) |

Methadone (n = 18,897) |

Natural and semi-synthetic opioids§ (n = 54,480) |

Opium and other and unspecified narcotics‖ (n = 7205) |

Co-involving another specified substance (n = 14,753) |

Without other specified substances (n = 4709) |

||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 69,264 (58.6%) | 12,039 (71.5%) | 16,934 (61.1%) | 11,639 (61.6%) | 30,623 (56.2%) | 4456 (61.8%) | 7665 (52.0%) | 2647 (56.2%) |

| Female | 48,944 (41.4%) | 4808 (28.5%) | 10,772 (38.9%) | 7258 (38.4%) | 23,857 (43.8%) | 2749 (38.2%) | 7088 (48.0%) | 2062 (43.8%) |

| Median age (IQR) | 43 (32–52) | 36 (29–48) | 39 (30–50) | 41 (31–50) | 44 (33–53) | 41 (32–50) | 47 (37–55) | 48 (37–58) |

| Race | ||||||||

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 1053 (0.9%) | 111 (0.7%) | 189 (0.7%) | 199 (1.1%) | 484 (0.9%) | 75 (1.0%) | 156 (1.1%) | 38 (0.8%) |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 1006 (0.9%) | 148 (0.9%) | 194 (0.7%) | 114 (0.6%) | 371 (0.7%) | 46 (0.6%) | 224 (1.5%) | 66 (1.4%) |

| Black | 5814 (4.9%) | 1122 (6.7%) | 1815 (6.6%) | 773 (4.1%) | 2597 (4.8%) | 376 (5.2%) | 661 (4.5%) | 192 (4.1%) |

| White | 110,335 (93.3%) | 15,466 (91.8%) | 25,508 (92.1%) | 17,811 (94.3%) | 51,028 (93.7%) | 6708 (93.1%) | 13,712 (92.9%) | 4413 (93.7%) |

| Hispanic origin | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 7526 (6.4%) | 1669 (9.9%) | 1894 (6.8%) | 1128 (6.0%) | 3033 (5.6%) | 474 (6.6%) | 996 (6.8%) | 252 (5.4%) |

| Not Hispanic | 110,043 (93.1%) | 15,044 (89.3%) | 25,650 (92.6%) | 17,637 (93.3%) | 51,212 (94%) | 6680 (92.7%) | 13,670 (92.7%) | 4435 (94.2%) |

| Hispanic status unknown | 639 (0.5%) | 134 (0.8%) | 162 (0.6%) | 132 (0.7%) | 235 (0.4%) | 51 (0.7%) | 87 (0.6%) | 22 (0.5%) |

| Type of overdose | ||||||||

| Accident | 96,040 (81.2%) | 16,269 (96.6%) | 24,889 (89.8%) | 16,929 (89.6%) | 45,034 (82.7%) | 6169 (85.6%) | 8396 (56.9%) | 2483 (52.7%) |

| Suicide | 15,430 (13.1%) | 199 (1.2%) | 1642 (5.9%) | 821 (4.3%) | 6305 (11.6%) | 552 (7.7%) | 5317 (36%) | 1728 (36.7%) |

| Homicide | 109 (0.1.0%) | 21 (0.1%) | 14 (0.1%) | 8 (0%) | 45 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | 16 (0.1%) | 18 (0.4%) |

| Undetermined | 6629 (5.6%) | 358 (2.1%) | 1161 (4.2%) | 1139 (6.0%) | 3096 (5.7%) | 480 (6.7%) | 1024 (6.9%) | 480 (10.2%) |

| Co-involving another specified non-opioid | 71,236 (60.3%) | 9829 (58.3%) | 16,762 (60.5%) | 9369 (49.6%) | 31,440 (57.7%) | 3834 (53.2%) | – | – |

| Cocaine | 15,787 (13.4%) | 4142 (24.6%) | 5338 (19.3%) | 2457 (13%) | 5372 (9.9%) | 1473 (20.4%) | 1700 (11.5%) | – |

| Psychostimulants* | 8632 (7.3%) | 2060 (12.2%) | 2847 (10.3%) | 998 (5.3%) | 3134 (5.8%) | 578 (8.0%) | 1289 (8.7%) | – |

| Alcohol | 19,252 (16.3%) | 2779 (16.5%) | 3741 (13.5%) | 1596 (8.4%) | 6940 (12.7%) | 939 (13.0%) | 6170 (41.8%) | – |

| Barbiturates | 2085 (1.8%) | 169 (1%) | 367 (1.3%) | 212 (1.1%) | 930 (1.7%) | 166 (2.3%) | 588 (4.0%) | – |

| Antidepressants | 22,195 (18.8%) | 1574 (9.3%) | 4276 (15.4%) | 3295 (17.4%) | 10,563 (19.4%) | 800 (11.1%) | 5487 (37.2%) | – |

| Antiepileptics and sedative-hypnotics† | 10,001 (8.5%) | 843 (5%) | 2437 (8.8%) | 997 (5.3%) | 5193 (9.5%) | 244 (3.4%) | 2190 (14.8%) | – |

| Antipsychotics | 9500 (8%) | 589 (3.5%) | 1797 (6.5%) | 1305 (6.9%) | 4727 (8.7%) | 261 (3.6%) | 2442 (16.6%) | – |

| Cannabis | 1786 (1.5%) | 287 (1.7%) | 469 (1.7%) | 233 (1.2%) | 781 (1.4%) | 235 (3.3%) | 254 (1.7%) | – |

| Other specified non-opioids | 20,039 (17%) | 1441 (8.6%) | 3971 (14.3%) | 2361 (12.5%) | 10,937 (20.1%) | 666 (9.2%) | 4295 (29.1%) | – |

| Co-involving another opioid | 98,746 (83.5%) | 9448 (56.1%) | 14,709 (53.1%) | 7410 (39.2%) | 16,308 (29.9%) | 2243 (31.1%) | – | – |

| Heroin | 16,847 (14.3%) | – | 6016 (21.7%) | 1120 (5.9%) | 3721 (6.8%) | 617 (8.6%) | – | – |

| Synthetic opioids‡ | 27,706 (23.4%) | 6016 (35.7%) | – | 1789 (9.5%) | 8591 (15.8%) | 587 (8.1%) | – | – |

| Methadone | 18,897 (16%) | 1120 (6.6%) | 1789 (6.5%) | – | 5132 (9.4%) | 592 (8.2%) | – | – |

| Natural and semi-synthetic opioids§ | 54,480 (46.1%) | 3721 (22.1%) | 8591 (31%) | 5132 (27.2%) | – | 988 (13.7%) | – | – |

| Opium and other and unspecified narcotics‖ | 7205 (6.1%) | 617 (3.7%) | 587 (2.1%) | 592 (3.1%) | 988 (1.8%) | – | – | – |

| Co-involving opioids, barbiturates, alcohol, cocaine, or other psychostimulants | 107,531 (91.0%) | – | – | – | – | – | 8785 (59.5%) | – |

| Includes unspecified substances | 61,055 (51.7%) | 6696 (39.7%) | 12,465 (45%) | 9792 (51.8%) | 30,340 (55.7%) | 3464 (48.1%) | 8435 (57.2%) | 2198 (46.7%) |

*Excluding cocaine

†Excluding benzodiazepines and barbiturates

‡Excluding methadone

§Excluding heroin and opium

‖Includes opium and ICD-10 code T40.6: other and unspecified narcotics

Percentages are calculated based on the number of events within each column. Overdose deaths involving multiple opioids are included in columns for each involved opioid class

Opioids were co-involved in 98,746 overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines (83.5%) (Table 2). Antidepressants were co-involved in 18.8% of deaths, alcohol was co-involved in 16.3% of deaths, cocaine in 13.4% of deaths, and other psychostimulants in 7.3% of deaths. A total of 10,677 benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths (9.0%) did not involve opioids, cocaine, other psychostimulants, barbiturates, or alcohol; among these deaths, 4709 involved no other specified substance.

Among opioids, natural and semi-synthetic opioids (e.g., morphine, oxycodone) were most frequently co-involved, followed by synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl). Overdose deaths co-involving benzodiazepines and opioids frequently involved at least one other non-opioid (Table 2). Alcohol and antidepressants were the most frequently co-involved substances among overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines but not opioids.

In overdose deaths co-involving benzodiazepines and opioids, 86.2% were classified as accidental, 8.5% as suicides, and 5.2% as undetermined intent. Among overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines but not opioids, 55.9% were classified as accidents, 36.2% as suicides, and 7.7% as undetermined intent. Overdose deaths involving both benzodiazepines and antidepressants but not opioids were classified as suicides in 51.4% of cases.

In the most recent year, 2019, 53.3% of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths co-involved synthetic opioids, 34.6% co-involved natural and semi-synthetic opioids, and 21.21.1% co-involved heroin (Table 3). Cocaine was co-involved in 18.7% of deaths, alcohols in 17.9%, other psychostimulants in 16.5%, and antidepressants in 16.3%.

Table 3.

Benzodiazepine-Involved Overdose Deaths During 2019 in the USA

|

Total (n= 9731) |

Co-involving opioids (n= 8310) |

Not involving opioids (n= 1421) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin (n = 2053) |

Synthetic opioids‡ (n = 5191) |

Methadone (n = 788) |

Natural and semi-synthetic opioids§ (n = 3371) |

Opium and other and unspecified narcotics‖ (n = 248) |

Co-involving another specified substance (n = 1207) |

Without other specified substances (n = 214) |

||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 5738 (59%) | 1420 (69.2%) | 3357 (64.7%) | 443 (56.2%) | 1810 (53.7%) | 140 (56.5%) | 614 (50.9%) | 118 (55.1%) |

| Female | 3993 (41%) | 633 (30.8%) | 1834 (35.3%) | 345 (43.8%) | 1561 (46.3%) | 108 (43.5%) | 593 (49.1%) | 96 (44.9%) |

| Median age (IQR) | 42 (32–54) | 38 (31–50) | 39 (30–51) | 44 (35–54) | 45 (34–56) | 41.5 (30–53) | 49 (38–58) | 52 (38–65.75) |

| Race | ||||||||

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 79 (0.8%) | 18 (0.9%) | 28 (0.5%) | 8 (1.0%) | 32 (0.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | 15 (1.2%) | – |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 105 (1.1%) | 16 (0.8%) | 42 (0.8%) | 3 (0.4%) | 24 (0.7%) | 2 (0.8%) | 29 (2.4%) | 6 (2.8%) |

| Black | 785 (8.1%) | 179 (8.7%) | 490 (9.4%) | 60 (7.6%) | 289 (8.6%) | 25 (10.1%) | 65 (5.4%) | 18 (8.4%) |

| White | 8762 (90%) | 1840 (89.6%) | 4631 (89.2%) | 717 (91.0%) | 3026 (89.8%) | 220 (88.7%) | 1098 (91%) | 190 (88.8%) |

| Hispanic origin | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 855 (8.8%) | 226 (11.0%) | 475 (9.2%) | 87 (11.0%) | 256 (7.6%) | 22 (8.9%) | 113 (9.4%) | 13 (6.1%) |

| Not Hispanic | 8820 (90.6%) | 1802 (87.8%) | 4680 (90.2%) | 693 (87.9%) | 3105 (92.1%) | 226 (91.1%) | 1092 (90.5%) | 200 (93.5%) |

| Hispanic status unknown | 56 (0.6%) | 25 (1.2%) | 36 (0.7%) | 8 (1.0%) | 10 (0.3%) | – | 2 (0.2%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Type of overdose | ||||||||

| Accident | 8412 (86.4%) | 2016 (98.2%) | 4883 (94.1%) | 734 (93.1%) | 2836 (84.1%) | 228 (91.9%) | 767 (63.5%) | 126 (58.9%) |

| Suicide | 961 (9.9%) | 14 (0.7%) | 148 (2.9%) | 19 (2.4%) | 406 (12%) | 11 (4.4%) | 368 (30.5%) | 75 (35.0%) |

| Homicide | 7 (0.1%) | – | 2 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) | – | 2 (0.2%) | – |

| Undetermined | 351 (3.6%) | 23 (1.1%) | 158 (3%) | 34 (4.3%) | 127 (3.8%) | 9 (3.6%) | 70 (5.8%) | 13 (6.1%) |

| Co-involving another specified non-opioid | 6660 (68.4%) | 1356 (66.0%) | 3355 (64.6%) | 480 (60.9%) | 2192 (65.0%) | 148 (59.7%) | 1207 (100%) | – |

| Cocaine | 1819 (18.7%) | 517 (25.2%) | 1267 (24.4%) | 112 (14.2%) | 414 (12.3%) | 72 (29.0%) | 169 (14.0%) | – |

| Psychostimulants* | 1606 (16.5%) | 441 (21.5%) | 898 (17.3%) | 91 (11.5%) | 440 (13.1%) | 56 (22.6%) | 224 (18.6%) | – |

| Alcohol | 1745 (17.9%) | 328 (16.0%) | 800 (15.4%) | 74 (9.4%) | 474 (14.1%) | 25 (10.1%) | 496 (41.1%) | – |

| Barbiturate | 128 (1.3%) | 11 (0.5%) | 42 (0.8%) | 13 (1.6%) | 37 (1.1%) | 6 (2.4%) | 46 (3.8%) | – |

| Antidepressants | 1589 (16.3%) | 183 (8.9%) | 589 (11.3%) | 129 (16.4%) | 622 (18.5%) | 6 (2.4%) | 412 (34.1%) | – |

| Antiepileptics and sedative-hypnotics† | 1321 (13.6%) | 188 (9.2%) | 557 (10.7%) | 126 (16.0%) | 591 (17.5%) | 7 (2.8%) | 242 (20.0%) | – |

| Antipsychotics | 754 (7.7%) | 90 (4.4%) | 268 (5.2%) | 72 (9.1%) | 261 (7.7%) | 3 (1.2%) | 208 (17.2%) | – |

| Cannabis | 206 (2.1%) | 36 (1.8%) | 119 (2.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 68 (2%) | 15 (6%) | 34 (2.8%) | – |

| Other specified non-opioids | 1676 (17.2%) | 204 (9.9%) | 648 (12.5%) | 126 (16.0%) | 713 (21.2%) | 12 (4.8%) | 378 (31.3%) | – |

| Co-involving another opioid | 8310 (85.4%) | 1569 (76.4%) | 2580 (49.7%) | 421 (53.4%) | 1578 (46.8%) | 92 (37.1%) | – | – |

| Heroin | 2053 (21.1%) | 2053 (100%) | 1384 (26.7%) | 145 (18.4%) | 397 (11.8%) | 35 (14.1%) | – | – |

| Synthetic opioids‡ | 5191 (53.3%) | 1384 (67.4%) | 5191 (100%) | 268 (34.0%) | 1293 (38.4%) | 54 (21.8%) | – | – |

| Methadone | 788 (8.1%) | 145 (7.1%) | 268 (5.2%) | 788 (100%) | 177 (5.3%) | 12 (4.8%) | – | – |

| Natural and semi-synthetic opioids§ | 3371 (34.6%) | 397 (19.3%) | 1293 (24.9%) | 177 (22.5%) | 3371 (100%) | 38 (15.3%) | – | – |

| Opium and other and unspecified narcotics‖ | 248 (2.5%) | 35 (1.7%) | 54 (1%) | 12 (1.5%) | 38 (1.1%) | 248 (100%) | – | – |

| Co-involving opioids, barbiturates, alcohol, cocaine, or other psychostimulants | 9107 (93.6%) | 2053 (100%) | 5191 (100%) | 788 (100%) | 3371 (100%) | 248 (100%) | 797 (66.0%) | – |

| Includes unspecified substances | 4398 (45.2%) | 777 (37.8%) | 1989 (38.3%) | 352 (44.7%) | 1743 (51.7%) | 112 (45.2%) | 671 (55.6%) | 95 (44.4%) |

*Excluding cocaine

†Excluding benzodiazepines and barbiturates

‡Excluding methadone

§Excluding heroin and opium

‖Other and unspecified includes opium and ICD-10 code T40.6: other and unspecified narcotics

Percentages are calculated based on the number of events within each column. Overdose deaths involving multiple opioids are included in columns for each involved opioid class

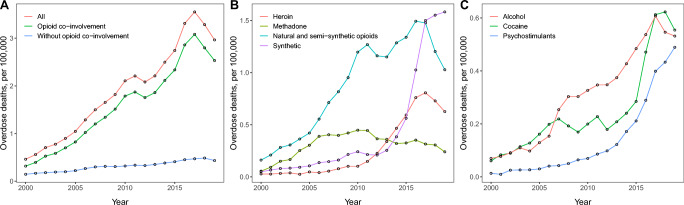

Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths increased from 0.46 per 100,000 individuals in 2000 to 3.55 per 100,000 individuals in 2017 before decreasing to 2.96 per 100,000 individuals in 2019 (Fig. 1A). Benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths co-involving opioids increased from 0.32 per 100,000 in 2000 to 3.08 per 100,000 in 2017 and decreased to 2.53 per 100,000 in 2019, while rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths not involving opioids increased from 0.14 per 100,000 in 2000 to 0.49 per 100,000 in 2018, decreasing to 0.43 per 100,000 in 2019 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Trends in benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality rates, by co-involved substances. A Overdose mortality rates by presence of any opioid. B Overdose mortality rates by co-involved opioid. C Overdose mortality rates by co-involved non-opioid. Rates of overdose mortality are presented per 100,000 individuals. Overdose deaths may co-involve multiple substances.

Rates of overdose deaths co-involving benzodiazepines and methadone peaked in 2010, while those co-involving benzodiazepines and natural and semi-synthetic opioids peaked in 2016 (Fig. 1B). Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths also involving heroin reached a maximum in 2017, while deaths co-involving synthetic opioids continued to increase through 2019 after a rapid increase from 2013 to 2017.

Benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths co-involving alcohol, cocaine, or other psychostimulants increased from 2000 to 2019 (Fig. 1C). Rates of overdose deaths co-involving benzodiazepines and alcohol reached a maximum in 2017, while rates of those co-involving benzodiazepines and cocaine reached a maximum in 2018. Rates of overdose deaths co-involving benzodiazepines and other psychostimulants increased monotonically during 2000–2019.

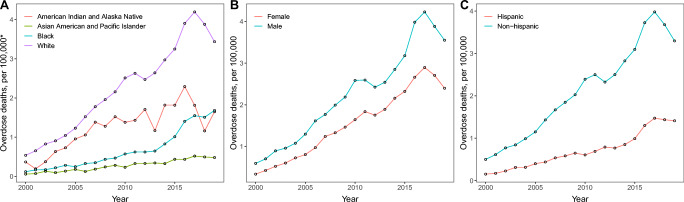

Benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality rates increased from 2000 to 2019 in both sexes, all racial groups, and among individuals of Hispanic and non-Hispanic origin (Fig. 2). Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality were highest among individuals identified as White throughout the study period (Fig. 2A), though mortality rates among individuals identified as White decreased markedly after 2017. In contrast, overdose mortality rates among individuals identified as Black continued to rise between 2017 and 2019. Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths among individuals identified as American Indian and Alaska Native reached a maximum in 2016, decreased markedly over 2017–2018, and increased in 2019.

Figure 2.

Trends in demographic characteristics of benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality. A Overdose mortality rates by race. B Overdose mortality rates by sex. C Overdose mortality rates by Hispanic origin. Rates of overdose mortality are presented per 100,000 individuals of the demographic group.

DISCUSSION

While previous studies have assessed benzodiazepine co-involvement in opioid-related overdose deaths, this is the first study to characterize the demographic characteristics, intentionality, and associated substances in all benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths.1–3 The study replicates the finding that most benzodiazepine-related overdose deaths co-involve opioids3 and has several additional findings with clinical implications. First, in contrast to the classic teaching that overdoses with benzodiazepines alone are rarely fatal,10 many benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths did not include other substances typically identified as high risk (opioids, stimulants, barbiturates, or alcohol). Second, suicide is a frequent cause of death among individuals who die from overdoses that involve benzodiazepines but not opioids. Third, alcohol is frequently co-involved in benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths, especially when opioids are not involved. Fourth, those who died from benzodiazepine-involved overdoses frequently consumed substances other than opioids, regardless of whether they also consumed opioids. Fifth, despite the rise in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths, natural and semi-synthetic opioids continued to be frequently co-involved in benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths in 2019. Sixth, although individuals identified as White had the highest rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality between 2000 and 2019, rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality among these individuals decreased from 2017 to 2019. In contrast, rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality increased among individuals identified as Black from 2017 to 2019. This finding aligns with trends in total and opioid-involved overdose mortality rates, which increased among Black individuals from 2017 to 2019 despite a slight decrease in rates among White individuals.11

The decreases in benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths co-involving methadone starting in 2010 and natural and semi-synthetic opioids starting in 2016 followed efforts to reduce both prescribing of these opioids and co-prescribing of benzodiazepines and opioids.12–14 The rapid increase in benzodiazepine-involved overdoses co-involving synthetic opioids and stimulants starting in 2013 follows broader trends in overdose deaths during this time.15–17

Strategies to reduce overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines should consider the co-involved substances, role of suicides, and demographics of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths. Interventions designed to reduce opioid and benzodiazepine co-prescribing and co-consumption, as well as efforts to increase naloxone availability, and to reduce alcohol consumption among those prescribed benzodiazepines, may help reduce benzodiazepine-involved overdoses. Suicide risk assessments, safety planning, and treating underlying suicidality may also reduce benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths. Interventions tailored for non-White communities, including reducing barriers to opioid use disorder treatment, may assist with reducing benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths in non-White individuals.18

Limitations

The sensitivity of toxicology testing and reporting patterns on death certificates may cause under-reporting of benzodiazepine or other substance involvement in overdose deaths. Changes in testing and reporting practices over time may affect longitudinal comparisons. Ascertaining and classifying intent in overdose deaths may not fully capture the spectrum of suicidal ideation prior to overdose deaths.19 Incorrect identification of race and Hispanic origin can occur on death certificates, particularly among American Indian and Alaska Native individuals.20 Further, bridged-race categories do not accurately describe racial identity for many individuals. Inclusion of code T50.9 may reflect agents that contributed to overdose deaths but were not included in specific counts of involved substances.

CONCLUSIONS

Rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths increased from 2000 to 2017, before decreasing during 2018–2019. The 2018–2019 period coincided with decreased rates of overdoses co-involving benzodiazepines and natural and semi-synthetic opioids. However, rates of benzodiazepine-involved overdoses continued to increase after 2017 among individuals identified as Black. Benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths often, but do not always, co-involve opioids, antidepressants, alcohol, cocaine, and other psychostimulants. Interventions to reduce benzodiazepine-involved overdose mortality should consider the demographics of, co-involved substances in, and presence of suicides among benzodiazepine-involved overdose deaths.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research in Addiction Medicine Scholars Program (National Institute on Drug Abuse R25DAO33211).

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Weiss has served as a consultant to Astellas Pharmaceuticals, Cerevel Therapeutics, Analgesic Solutions, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kleinman has received funding from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Discovery Fund and the Research in Addiction Medicine Scholars Program (National Institute on Drug Abuse R25DAO33211) and travel awards from the American Psychiatric Association and the American Academy on Addiction Psychiatry.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gladden RM. Changes in opioid-involved overdose deaths by opioid type and presence of benzodiazepines, cocaine, and methamphetamine — 25 states, July–December 2017 to January–June 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6834a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Tori ME, Larochelle MR, Naimi TS. Alcohol or benzodiazepine co-involvement with opioid overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202361. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. Published January 29, 2021. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- 4.Lembke A, Papac J, Humphreys K. Our other prescription drug problem. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):693–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mortality multiple cause files. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/vitalstatsonline.htm

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. About the National Vital Statistics System. Published January 4, 2016. Accessed May 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/about_nvss.htm

- 7.Murphy S, Xu J, Kochanek K, Arias E, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2021;69(13):83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics. U.S. Census populations with bridged race categories. Published July 6, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race.htm

- 9.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longo LP, Johnson B. Addiction: Part I. Benzodiazepines-side effects, abuse risk and alternatives. AFP. 2000;61(7):2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER. Published December 22, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- 12.Jones CM. Trends in methadone distribution for pain treatment, methadone diversion, and overdose deaths — United States, 2002–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohnert ASB, Guy GP, Losby JL. Opioid prescribing in the United States before and after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2016 opioid guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(6):367–375. doi: 10.7326/M18-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Changes in synthetic opioid involvement in drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2010-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(17):1819–1821. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic | drug overdose | CDC Injury Center. Published March 17, 2021. Accessed May 30, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

- 17.Ciccarone D. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344–350. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James K, Jordan A. The opioid crisis in Black communities. J Law Med Ethics. 2018;46(2):404–421. doi: 10.1177/1073110518782949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connery HS, Taghian N, Kim J, et al. Suicidal motivations reported by opioid overdose survivors: a cross-sectional study of adults with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2019;205:107612. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arias E, Heron M, National Center for Health Statistics, Hakes J, US Census Bureau. The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;(172):1-21. [PubMed]