Abstract

Pharynx/Larynx is an uncommon site of involvement of sarcoidosis. Isolated pharyngo-laryngeal sarcoidosis is extremely rare as most of the cases are part from multiorgan and systemic sarcoidosis. Pharyngo-laryngeal sarcoidosis is usually asymptomatic which could be attributed to its rare incidence as many cases pass unnoticed. Symptomatic cases usually present with hoarseness of voice. As the disease progress, the patient can present with progressive dysphagia to solid and liquid with globus sensation. We described an atypical involvement of almost the whole length of the pharynx with extension into the larynx in a 51-year-old woman who presented with progressive dysphagia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to describe the imaging features of sarcoidosis involvement of the pharynx and larynx.

Keywords: Pharyngeal/laryngeal sarcoidosis, CT, MRI, dysphagia

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a noncaseating granulomatous disease that most commonly affects the lungs and can affect any organ in the body causing chronic inflammation [1]. The exact cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, however smoking, obesity and occupational silica exposure are known risk factors [2].

Sarcoidosis has an annual incidence of 17-43 per 100.00 in Blacks, 5-12 per 100.00 in Whites and 1-3 per 100.00 in Asians and Hispanics [3]. The commonly affected age in men is 40-59 years and in women is 50-69 years [3]. The incidence of sarcoidosis has declined in young people and the age of diagnosis has shifted more towards old age [2,4].

The lung and intrathoracic lymph nodes are the most common affected organs (>90% of cases) but more than half of these cases are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis [3]. Dry cough, dyspnea, and chest pain are the most common symptoms [3,5,6]. Pulmonary fibrosis can result in chronic disease, and it increases the risk of pulmonary hypertension and respiratory failure [3]. Skin, extrathoracic lymph node, eye, and liver involvement is also common [3,7]. Constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, weight loss and fatigue) are more prominent at the onset of disease and they occur in 30% of cases and occur more in African Americans [6,8].

Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) involvement occurs in 6% of patients [9]. Women have twice the rate of incidence as men [9]. SURT includes sino-nasal (1%-6%) and pharyngo-laryngeal (1%-5%) affection [10]. It can be isolated or, more commonly, a part of multisystemic sarcoidosis [11]. Sino-nasal sarcoidosis is the most common form of SURT (85%) [10,12]. Pharyngo-laryngeal involvement is less common and more difficult to identify (30%) [10,13]. Pharyngeal involvement is usually asymptomatic because it is a hollow organ [14]. In this report, we presented the imaging feature on CT and MRI of an isolated pharyngo-laryngeal sarcoidosis.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old female complained of difficulty swallowing for solid foods, pulling sensation in her throat, coughing and excessive mucous in her throat whenever she eats and shortness of breath for 6 months. Modified barium swallow was normal except for stasis of solid foods at the epiglottis. Trans-nasal flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy revealed bilateral pharyngeal wall fullness with narrowing of the nasopharynx down to the larynx, effaced pyriform sinuses and enlarged adenoid pad with excessive mucous. The mucosa over the posterior and lateral pharyngeal walls was smooth. The nose, epiglottis and larynx were normal.

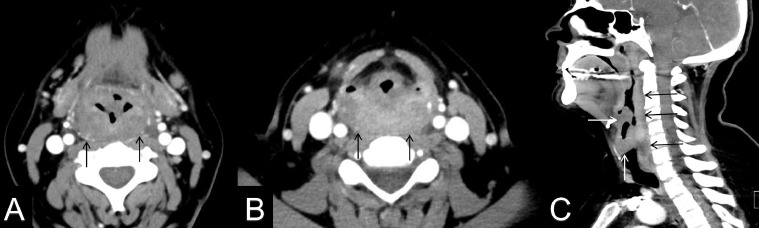

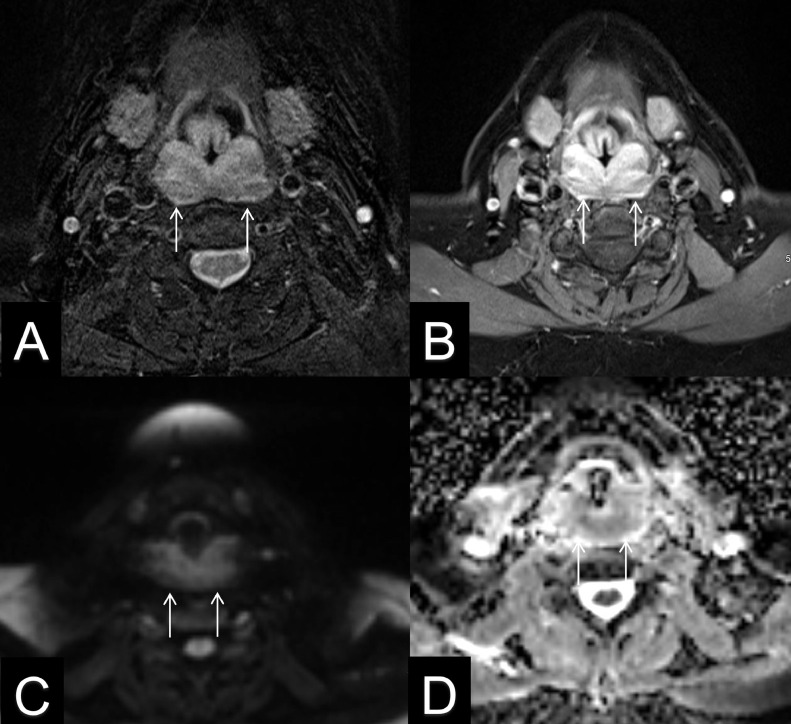

A CT of the nasal sinuses was normal and contrast-enhanced CT of the neck demonstrated diffuse submucosal thickening of the pharyngeal wall spanning from oropharynx into cervical esophagus (Fig. 1). There was involvement of glottic and supraglottic tissues including the epiglottis and aryepiglottic folds without cervical lymphadenopathy nor abscess formation. The imaging features were suspicious for neoplastic process. Follow-up contrast-enhanced MRI of the neck was performed and confirmed diffuse submucosal pharyngeal thickening with involvement of the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and piriform sinuses (Fig. 2). These areas had low T2/STIR signal and heterogenous enhancement in the post contrast images (Fig. 2). There was mild restricted diffusion. Given the low T2 signal, mild restricted diffusion, and heterogenous enhancement; chronic inflammatory disease such as sarcoidosis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis was pursued. The differential diagnosis was non-Hodgkin lymphoma or submucosal metastatic disease. The patient's labs were normal except for an elevated ESR of 42 mm/h and elevated ACE levels. Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy was again performed and biopsy has been taken. The pathological evaluation showed chronic noncaseating granuloma which was consistent with sarcoidosis. The patient's dysphagia progressed to solids and fluids with worsening congestion and choking sensation. Emergent tracheostomy was performed, and steroid burst of 60 mg/d was started with 10mg taper. The patient was stable post operatively with gradual improvement.

Fig. 1.

51-year-old female with isolated pharyngeal/laryngeal sarcoidosis. Axial contrast-enhanced CT images of the neck at the hypopharyngeal level (A), and piriform sinuses (B) show diffuse submucosal thickening of the pharyngeal wall with significant compression of the piriform sinuses (black arrows). Sagittal contrast-enhanced CT image of the neck demonstrates the full length of pharyngeal involvement, spanning from oropharynx to the cervical esophagus (black arrows). Laryngeal disease is also noted along the true vocal cords and epiglottis (white arrows).

Fig. 2.

Fifty-one-year-old female with isolated pharyngeal/laryngeal sarcoidosis. Axial T2 weighted image with fat saturation (A), and T1 contrast-enhanced image with fat saturation (B) demonstrate diffuse submucosal thickening of the pharyngeal wall and epiglottis with low T2 signal and heterogeneous enhancement in the post contrast image (arrows). Axial B1000 diffusion weighted image (C), and apparent diffusion coefficient (D) show mild hyperintense signal on B1000 image with corresponding dark signal on ADC, consistent with restricted diffusion (arrows).

Discussion

Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) involvement occurs in 6% of patients [9]. Symptoms of sino-nasal sarcoidosis (SNS) include nasal stuffiness (90%), anosmia (70%), rhinorrhea (70%) and purplish coloring with granulations and crusting of mucosa (50%) [15]. Hoarseness of voice is the most common symptom in pharyngo-laryngeal sarcoidosis (PLS) [10]. Parotid gland involvement is characteristic for SURT and usually early [15,16].

The symptoms of SURT are nonspecific and can be explained by much more common etiologies (eg, allergic rhinitis, sinusitis and laryngitis), so the duration of symptoms before diagnosis could last up to be years [10]. SURT should be suspected in patients with persistent upper airway symptoms of unknown cause [13].

Pharyngo-laryngeal involvement can be asymptomatic at first, but as the disease progresses, symptoms start to occur (eg, hoarseness of voice, ear fullness, dysphagia, dyspnea, and globus sensation) [6]. Airway obstruction due to edema of supraglottic structures (ie, epiglottis, arytenoids, and false vocal cords) is life-threatening and presents with progressive hoarseness, stridor, and acute respiratory distress [6,17]. Because of the life-threatening nature of laryngeal involvement, physicians should have a low threshold for performing laryngoscopy [18]. Adenoid and tonsillar affection occur in 2.4% and can cause obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [8].

Diagnosis depends on clinical, laboratory and radiological findings in addition to biopsy showing noncaseating granulomas (necessary to make the diagnosis) [17].

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated in 60% of cases. Leukopenia, eosinophilia, anemia, Hypercalcemia, elevated angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, hyper-gammaglobulinemia, and increased alkaline phosphatase (APL) are present in some of the systemic sarcoidosis cases [8].

Lateral radiograph of the neck usually shows “thumb sign” resembling acute laryngitis because of epiglottic edema in severe disease [19]. CT of the neck can show variable lesions including multiple hypodense nodules and submucosal thickening of the pharynx (causing narrowing of pharyngeal space) and supraglottic structures (ie, epiglottis, arytenoid folds, and false vocal cords) [20]. Localized masses, cervical lymphadenopathy and obliteration of pyriform sinuses occasionally appear on CT [21]. CT scan is inconclusive for isolated PLS diagnosis [22]. 18 F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) shows increased uptake of 18F-FDG by the granulomatous lesions. It has a diagnostic sensitivity of 85% in localization for PLS lesions [22]. Because these PET/CT results are concerning for malignancy and they are nonspecific for sarcoidosis, a biopsy is mandated to exclude malignancy and confirm the diagnosis [22]. MRI shows submucosal thickening with hypointensity on T2-wighted images that enhance after gadolinium [23]. Most of these lesions demonstrate restricted diffusion on diffusion weighted images. Differential diagnosis is malignancy (eg, non-Hodgkin lymphoma or metastasis) and it appears as heterogenous signal on T1 and T2-wighted images and as hypointensity on early and delayed images after gadolinium administration [23].

Exclusion of other granulomatous diseases is essential to confirm the diagnosis including TB (using acid-fast bacilli, purified protein derivative and culture), Fungal infection (using fungal stain and culture), Wagener's granulomatosis (using cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (cANCA)) and syphilis (using venereal disease research laboratory or rapid plasma reagin (VDRL/RPR)) [6,10].

The mainstay of treatment for pharyngo-laryngeal sarcoidosis is oral corticosteroids [24]. Mild cases can be treated with low dose steroids [25]. High dose oral corticosteroids (40-60 mg/day for 6-12 months) are required in severe symptoms [26]. Intralesional corticosteroid injection using direct laryngoscope is another option for well-circumscribed lesions [25]. The rate of SURT response to treatment is not consistent [10]. Clofazimine, an antileprosy drug using small doses (100 mg for 10 days) is a good option for cases refractory to corticosteroids and it has good outcome [25]. Surgical treatment (eg, tracheostomy) is reserved to cases with life-threatening complications that failed medical treatment or do not have enough time to receive it [10]. Local irradiation is an alternative to tracheostomy [18,27]. Transoral partial supraglottic resection using the CO2 laser is another alternative [28]. The rate of spontaneous remission is 60%-70% and chronic affection occurs in 10%-20% [6]. In most cases sarcoidosis has a benign course and does not increase the mortality in the affected individuals more than that of the general population [3]. Mortalities occur from cardiac, pulmonary or neurological complications at a rate of 1%-5% [6].

Conclusion

Pharyngo-laryngeal sarcoidosis (PLS) is a rare form of sarcoidosis. PLS presents with non-specific symptoms and it should be included in any differential diagnosis for these symptoms. PLS is a severe form of sarcoidosis and it has variable and unpredictable course and could reach the point of life-threatening complications and also have inconsistent response to treatment. It is imperative to closely follow-upon these patients to monitor the progression of disease and the emergence of complications. Radiologists play an important role in the diagnosis and follow-up of the disease by correlating imaging and clinical-pathologic findings.

Patient consent

The patient gave a consent for publication.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment: None.

References

- 1.Song M., Manansala M., Parmar P.J., Ascoli C., Rubinstein I., Sweiss N.J. Sarcoidosis and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2021;27(5):448–454. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arkema E.V., Cozier Y.C. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis: current findings and future directions. Therapeut Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9(11):227–240. doi: 10.1177/2040622318790197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ungprasert P., Carmona E.M., Utz J.P., Ryu J.H., Crowson C.S., Matteson E.L. Vol. 91. 2016. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis 1946-2013: a population-based study; pp. 183–188. (Mayo Clin Proc). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawahata M., Sugiyama Y. An epidemiological perspective of the pathology and etiology of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;33(2):112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baughman R.P., Culver D.A., Judson M.A. A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(5):573–581. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-0865CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartzbauer H.R., Tami T.A. Ear, nose, and throat manifestations of sarcoidosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36(4):673–684. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(03)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulati S., Krossnes B., Olofsson J., Danielsen A. Sinonasal involvement in sarcoidosis: a report of seven cases and review of literature. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2012;269(3):891–896. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayock R.L., Bertrand P., Morrison C.E., Scott J.H. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med. 1963;35:67–89. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(63)90165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James D.G., Barter S., Jash D., MacKinnon D.M., Carstairs L.S. Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96(8):711–718. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100093026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panselinas E., Halstead L., Schlosser R.J., Judson M.A. Clinical manifestations, radiographic findings, treatment options, and outcome in sarcoidosis patients with upper respiratory tract involvement. South Med J. 2010;103(9):870–875. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181ebcda5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun J.J., Riehm S., Imperiale A., Schultz-Carpentier A.S., Gentine A., de Blay F. [Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract] Rev Mal Respir. 2011;28(2):164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeitlin J.F., Tami T.A., Baughman R., Winget D. Nasal and sinus manifestations of sarcoidosis. Am J Rhinol. 2000;14(3):157–161. doi: 10.2500/105065800782102753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rottoli P., Bargagli E., Chidichimo C., Nuti D., Cintorino M., Ginanneschi C., et al. Sarcoidosis with upper respiratory tract involvement. Respir Med. 2006;100(2):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roger G., Gallas D., Tashjian G., Baculard A., Tournier G., Garabedian E.N. Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1994;30(3):233–240. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(94)90065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aubart F.C., Ouayoun M., Brauner M., Attali P., Kambouchner M., Valeyre D., et al. Sinonasal involvement in sarcoidosis: a case-control study of 20 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(6):365–371. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000236955.79966.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baughman R.P., Lower E.E., Tami T. Upper airway.4: sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) Thorax. 2010;65(2):181–186. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neel H.B., 3rd, McDonald T.J. Laryngeal sarcoidosis: report of 13 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91:359–362. doi: 10.1177/000348948209100406. 4 Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carasso B. Sarcoidosis of the larynx causing airway obstruction. Chest. 1974;65(6):693–695. doi: 10.1378/chest.65.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovell L., Clunie G.M., Al-Yaghchi C., Roe J., Sandhu G. Laryngeal sarcoidosis and swallowing: what do we know about dysphagia assessment and management in this population? Dysphagia. 2022;37(3):548–557. doi: 10.1007/s00455-021-10305-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plaschke C.C., Owen H.H., Rasmussen N. Clinically isolated laryngeal sarcoidosis. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2011;268(4):575–580. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1449-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palacios E., Smith A., Gupta N. Laryngeal sarcoidosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87(5):252–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun J.J., Imperiale A., Schultz P., Molard A., Charpiot A., Gentine A. Pharyngolaryngeal sarcoidosis: report of 12 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:463–465. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmucci S., Torrisi S.E., Caltabiano D.C., Puglisi S., Lentini V., Grassedonio E., et al. Clinical and radiological features of extra-pulmonary sarcoidosis: a pictorial essay. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(4):571–587. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agrawal Y., Godin D.A., Belafsky P.C. Cytotoxic agents in the treatment of laryngeal sarcoidosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Voice. 2006;20(3):481–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridder G.J., Strohhäcker H., Golz A., Löhle E., Fradis M. Laryngeal sarcoidosis: treatment with the antileprosy drug clofazimine. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109(12):1146–1149. doi: 10.1177/000348940010901212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moraes BT N.L., Brasil OOC, Pedroso JES, Junior JESM. Laryngeal sarcoidosis: literature review. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;15(3):359–364. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fogel T.D., Weissberg J.B., Dobular K., Kirchner J.A. Radiotherapy in sarcoidosis of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(9):1223–1225. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198409000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruff T., Bellens E.E. Sarcoidosis of the larynx treated with CO2 laser. J Otolaryngol. 1985;14(4):245–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]