Abstract

To prepare medium-chain-length poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) with altered physical properties, we generated recombinant Escherichia coli strains that synthesized PHAs with altered monomer compositions. Experiments with different substrates (fatty acids with different chain lengths) or different E. coli hosts failed to produce PHAs with altered physical properties. Therefore, we engineered a new potential PHA synthetic pathway, in which ketoacyl-coenzyme A (CoA) intermediates derived from the β-oxidation cycle are accumulated and led to the PHA polymerase precursor R-3-hydroxyalkanoates in E. coli hosts. By introducing the poly-3-hydroxybutyrate acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhbB) from Ralstonia eutropha and blocking the ketoacyl-CoA degradation step of the β-oxidation, the ketoacyl-CoA intermediate was accumulated and reduced to the PHA precursor. Introduction of the phbB gene not only caused significant changes in the monomer composition but also caused changes of the physical properties of the PHA, such as increase of polymer size and loss of the melting point. The present study demonstrates that pathway engineering can be a useful approach for producing PHAs with engineered physical properties.

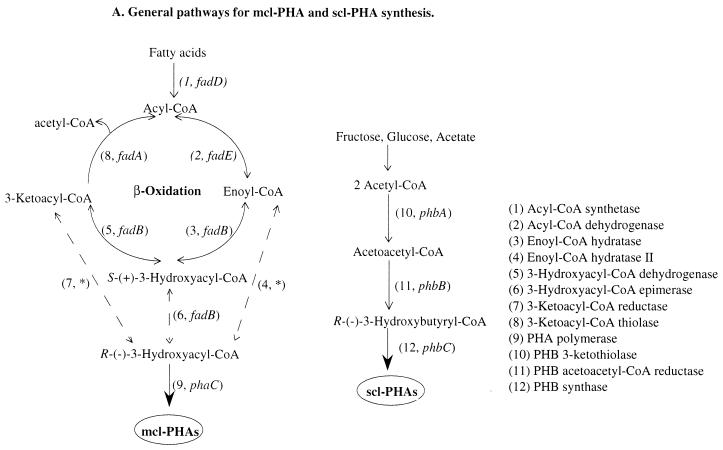

Poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), which are produced as intracellular storage material by many bacterial species, have attracted considerable attention due to their potential applications as biodegradable plastics and as sources of valuable chiral synthons (13). Based on detailed surveys, Steinbüchel and coworkers have classified PHAs into two groups (38), which are synthesized via different pathways (Fig. 1A). One group, short-chain-length PHAs (scl-PHAs), contains 3-hydroxyalkanoate monomers with chain lengths from C4 to C5. Another group, medium-chain-length PHAs (mcl-PHAs), are characterized by 3-hydroxyalkanoate monomers with chain lengths from C6 to C14.

FIG. 1.

General and modified pathways for the synthesis of mcl-PHA precursors. (A) Possible links between mcl-PHA synthesis and fatty acid degradation (left) and the general pathway for PHB synthesis in R. eutropha (right) are outlined. All enzymatic activities are numbered as indicated on the right. Genes encoding these enzymes that have not been identified are indicated with an asterisk. Dashed lines indicate pathways or reactions that are theoretically possible but might not take place due to limited concentrations of the β-oxidation intermediates. (B) Modified pathway for mcl-PHA synthesis in the E. coli fadB mutant. The fadB mutation blocks β-oxidation at the 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase step (cross), which channels substrates to mcl-PHA. The introduced phaC gene enables mcl-PHA synthesis, if sufficient substrate is available. The thick dashed arrow indicates the PHB acetoacetyl-CoA reductase activity encoded by phbB, cloned into the host. Reduction of ketoacyl-CoA intermediates is theoretically possible but might not take place due to limited 3-ketoacyl-CoA concentrations or limited enzyme activity for the mcl acyl-CoA β-oxidation intermediates. (C) Construct analogous to that seen in panel B with the host E. coli fadA mutant. This modified pathway was designed to increase the supply of mcl-PHA precursors by introduction of phbB in addition to blocking β-oxidation at the 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. The cross indicates a block of 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. The thick solid arrow indicates the postulated channeling of ketoacyl-CoA from β-oxidation to PHA.

It is known that PHAs are synthesized by polymerization of coenzyme A (CoA)-linked R-3-hydroxy fatty acids through one of several PHA polymerases (PhaC) (see a recent review [21]). The synthesis of such CoA substrates can occur by a variety of pathways, the simplest of which uses β-ketothiolase (PhbA) and acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhbB) to synthesize precursors for scl-PHA polymerases such as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthase (PhbC) in Ralstonia eutropha (25, 26) (Fig. 1A). mcl-PHA CoA-linked precursors can be generated through fatty acid β-oxidation that produces acyl-CoA intermediates such as enoyl-CoA, 3-ketoacyl-CoA, and/or S-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA when fatty acids are used as sole carbon sources (14, 16, 39, 40) (Fig. 1A).

Effort has been devoted in recent years to increasing PHA yields and productivity. Achieving production costs that are in the same range as those of chemically synthesized plastics may be feasible, given the recent creation of PHA-producing transgenic plants (22, 27, 40, 41). Equally important in the production of PHAs is the control of the fundamental properties of the polymer. The production of PHA with specific monomer units has demonstrated that the monomer unit composition significantly affects the final properties of the polymer product (41). To influence rationally these properties in the production of organisms, it is necessary to control and direct the production of PHA precursors. Various approaches have been used to modify PHA monomer compositions. One example is cofeeding of different substrates, such as for the production of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate (5), and blending polymer poly(3-hydroxy-5-phenylvalerates) and poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates (19). So far, modification of monomer compositions of mcl-PHAs has not been feasible since mcl-PHA precursors are derived from fatty acid metabolism and their concentrations are difficult to control.

Biosynthesis of these polymers in host organisms that do not naturally produce PHA allows modulation of biosynthetic enzymes and therefore allows one to achieve substrate levels that are difficult to achieve in a native host strain for the study of PHA production (18). In addition, introduction of specific genes into an organism having a suitably modified PHA synthetic pathway may allow extension and regulation of the range of compounds that can be produced. Escherichia coli is one of these useful hosts.

Previously, it has been reported that E. coli strains defective in the β-oxidation pathway are able to accumulate mcl-PHA when equipped with a PHA polymerase (29, 31). There are two PHA polymerases that are encoded by phaC1 and phaC2 in Pseudomonas oleovorans and P. aeruginosa (16, 39). The presence of one of these two polymerases is sufficient for PHA production in E. coli fatty acid degradation mutants (29, 31). Recently, it was found that inhibition of the β-oxidation thiolase step resulted in an increase in the availability of substrate for PHA synthesis (30). Therefore, engineering of E. coli to extend the range and distribution of precursors which can be channeled into mcl-PHA may lead to interesting PHA variants for application and development studies and is likely to extend the available chiral synthon pool as well.

In this study, we selected two E. coli mutants, JMU193 (fadR fadB) and JMU194 (fadR fadA), to investigate PHA accumulation. Our results revealed that ketoacyl-CoA intermediates of the β-oxidation cycle are potential precursors for PHA synthesis. By modifying relevant enzyme and substrate levels, we were able to redirect ketoacyl-CoA β-oxidation intermediates into mcl-PHA, and polymers with altered monomer composition and different physical properties were obtained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The following E. coli strains were used in this study: JMU193 (fadR::Tn10 fadB64) (32) and JMU194 (fadR::Tn10 fadA30) (32). Plasmids pETQ2 (31) and pBTC2 carrying phaC2 and pET901 carrying phbB were used to construct recombinants capable of PHA synthesis. pGEc404 carrying phaC2 (16), pBS20 carrying phbCAB (36), pBCKS (Promega), pUC19 (43), pVLT35 (3), and pCK01 (6) were used for the construction of pBTC2 and pET901. pETQ102, pET104, pBTC2′, and pET901′ were intermediate plasmids during the construction of pBTC2 and pET901.

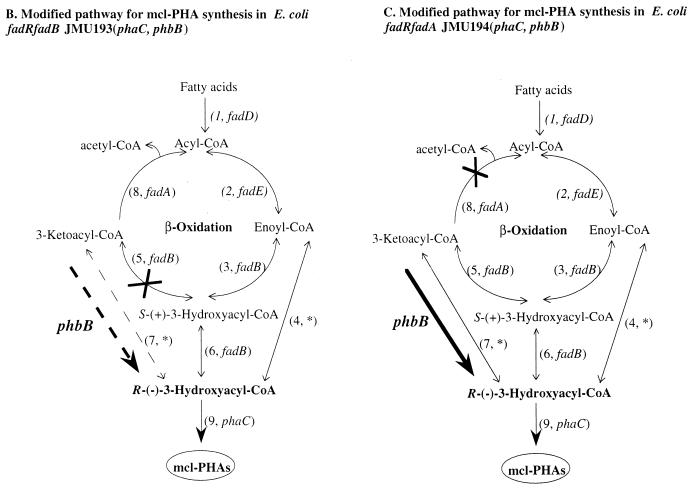

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Isolation and analysis of plasmid DNA were carried out according to the method of Sambrook et al. (33). Transformations of E. coli competent cells were done according to standard procedures (33). Plasmids pBTC2 and pET901 were constructed as illustrated in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the strategy to construct plasmids pBTC2 and pET901. Only the relevant cloned gene(s) and restriction site(s) are shown. (A) pBTC2 contains the phaC2 gene of P. oleovorans expressed through the Ptac promoter. (B) pET901 contains the phbB gene of R. eutropha expressed through the Plac promoter.

Media and culture conditions.

E. coli recombinants were grown at 37°C in complex Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (33). To allow accumulation of intracellular PHA, 0.1NE2 minimal medium (15) was used, 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract was added to the media as the carbon source to support growth. Fatty acids were prepared as previously described (17) and supplied as indicated in the medium for PHA production and possible carbon sources. Cells were induced with 200 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at the early exponential phase. If necessary, the following antibiotics were added: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml. Cell growth was monitored by measuring optical density at 450 nm (42).

PHB acetoacyl-CoA reductase assay.

For enzymatic analysis, precultures were grown in LB medium for 8 h at 37°C and then transferred into 0.1NE2 minimal medium with 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract with a 1:100 dilution. Cells were induced with 200 μM IPTG at early exponential phase and harvested at late exponential phase, washed once with 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and resuspended in a 10% volume of the same buffer. Cells were then disrupted in 200-μl aliquots by sonication. Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad protein assay. Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase activity was monitored at 340 nm by the oxidation of NADPH during reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA (35). Then, 25 μl of crude extract and 25 μl of 10 mM NADPH were mixed with 500 μl of buffer (120 mM potassium phosphate [pH 5.5], 24 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol), and 455 μl of H2O. The reaction was started by adding 5 μl of 7 mM acetoacetyl-CoA. One unit is defined as 1 μmol of NADPH depletion/min.

Incorporation of monomers into preexisting PHA.

Cells were cultivated on 0.1NE2 minimal medium with 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract and 2 mM hexadecanoate as described above. A pulse of 0.5 mM pentadecanoate was added to the culture at the time indicated. PHA compositions were analyzed by gas chromatography as previously described (20), and C7 and C9 monomer incorporation rates in preexisting C-even number PHA were determined.

Extraction of PHA.

Lyophilized cells (500 to 1,000 mg) were extracted with 150 ml of methylene chloride (CH2Cl2) for at least 8 h at 50°C. The cell extract was filtered, and the solvent was evaporated (Buechi Rotavapor) until <15 ml of extract remained. PHA was recrystallized by dropping the extract into 10 volumes of well-stirred, ice-cold methanol. Methanol solutions were then filtered through Zetapor filter membranes (CUNO, Inc., Meriden, Conn.). Polymer was recovered from the filters by dissolving it in chloroform and evaporating the solvent. The polymer was stored in the dark at room temperature for further analysis.

Determination of PHA.

To determine the presence and composition of PHA, lyophilized cells or isolated PHA were treated with H2SO4-methanol (85/15 [vol/vol]) in CHCl3 (containing 0.1 mg of methyl benzoate/ml) as previously described (20). The methanolyzed PHA monomers were analyzed by using a CP-Sil 5 CB column (Chrompack) on a gas chromatograph (Fison) (20). Splitless injection, an attenuation of 1, and a range of 0 were used to reach maximum sensitivity.

Molecular weight determination.

The molecular weight measurements were done by gel permeation chromatography. Samples were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran and run through a PL-Gel C 5-μm column. Signals were detected using capillary viscosimetry (Viscotek 502), light scattering (small angle laser light scattering detector, KMX-6), and light refraction (differential high-temperature refractometer [Knauer]) measurements. The column was calibrated with polystyrene standards.

DSC measurement.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) spectra (melting temperatures [Tm], enthalpy of fusion (ΔHm), and glass transition temperatures [Tg]) were recorded in a temperature range of −60 to 80°C on a Netzsch DSC 200 Perkin-Elmer model DSC-4 equipped with a cooling accessory under a nitrogen flow of 30 ml/min. PHA samples of 3 mg were encapsulated in aluminum pans and heated from −60 to 80°C at a rate of 10°C/min. The Tg was taken as the midpoint of the heating capacity change.

RESULTS

In this study E. coli fadR fadA and fadR fadB mutants (JMU194 and JMU193, respectively) were used through the whole study. The fadR gene encodes a protein that exerts negative control over genes necessary for fatty acid oxidation (2, 4, 17, 23). A mutation in fadR derepresses transcription of these genes, as a result of which the fad genes are constitutively expressed, rendering E. coli capable of growth on mcl fatty acids (2, 4). The fadA gene encodes 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (Fig. 1), and the fadB gene encodes four enzyme activities (Fig. 1): enoyl-CoA hydratase, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase, Δ3-cis-Δ2-trans-enoyl-CoA isomerase (not included in Fig. 1), and 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA epimerase (2, 4, 17, 23). Mutations in fadA or fadB block fatty acid oxidation and result in accumulation of specific intermediates.

Utilization of different substrates for PHA formation in a fadR fadB negative recombinant E. coli.

The E. coli fatty acid catabolism mutant JMU193, which lacks 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (24, 37) (Fig. 1B), was equipped with the PHA polymerase 2 from P. oleovorans GPo1 (16) and analyzed for PHA formation from a number of different fatty acids ranging from C6 to C18. Table 1 shows that the highest PHA contents (ca. 4% of cell dry weight [cdw]) were obtained during growth in the presence of longer-chain-length alkanoates of C16 to C18. However, the composition of PHAs formed from the tested alkanoates did not vary significantly with changes of alkanoate chain length. The polymer produced from odd-chain-length fatty acids consisted mainly of 3-hydroxyheptanoate (C7) and 3-hydroxynonanoate (C9), while the dominant even-chain-length monomers are 3-hydroxyhexanoate (C6), 3-hydroxyoctanoate (C8), and 3-hydroxydecanoate (C10).

TABLE 1.

Formation of PHAs by E. coli JMU193(pETQ2) grown in the presence of n-alkanoates

| Alkanoatesa | PHAb (% of cdw) | Monomer composition (mol%)c

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6 | C7 | C8 | C9 | C10 | ||

| Octanoate | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0d | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonanoate | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0 | 73 | 0 | 27 | 0 |

| Decanoate | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 83 | 0 | 17 |

| Undecanoate | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 0 | 72 | 0 | 28 | 0 |

| Dodecanoate | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 7 | 0 | 89 | 0 | 4 |

| Tridecanoate | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 0 | 71 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Tetradecanoate | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 7 | 0 | 86 | 0 | 7 |

| Pentadecanoate | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0 | 77 | 0 | 23 | 0 |

| Hexadecanoate | 4.1 ± 1.8 | 6 | 0 | 88 | 0 | 6 |

| Heptadecanoate | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| Octadecanoate | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 7 | 0 | 88 | 0 | 5 |

The E. coli recombinant was grown on 0.1NE2 minimal medium with 0.2% yeast extract and different alkanoates as indicated in this table.

The amount of PHA is given as a percentage (average ± the standard deviation) of the cdw.

The monomer composition is given as a molar percentage. C6, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; C7, 3-hydroxyheptanoate; C8, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; C9, 3-hydroxynonanoate; C10, 3-hydroxydecanoate.

0, <0.1%.

From these results it can be concluded that different-chain-length alkanoates supplied to a given E. coli recombinant lead to essentially identical C6 to C10 acyl-CoA levels, resulting in a rather constant PHA monomer composition.

PHA formation by E. coli recombinants defective in different steps of the β-oxidation.

Since the metabolic status, including the concentrations of metabolites and the rate of metabolite formation, may differ from one strain to another, it is plausible that the intracellular content and the composition of mcl-PHAs formed from such intermediates will vary from strain to strain. Thus, E. coli JMU194 (fadR fadA), a mutant which lacks 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase activity (24, 37) (Fig. 1C), was compared with JMU193 for PHA formation. To control the expression of phaC2, plasmid pBTC2 (Fig. 2A) containing phaC2 of P. oleovorans GPo1 expressed through the Ptac promoter was introduced in JMU193 and JMU194, and the recombinants were cultivated on medium containing hexadecanoate.

Both recombinants exhibited similar growth behaviors on the medium used, with an exponential growth rate of 0.14 h−1. However, E. coli JMU194(pBTC2) showed a sevenfold-higher monomer incorporation rate (60 nmol/mg of cdw/min) after 36 h of cultivation than did E. coli JMU193(pBTC2) (Table 2). There was also a significant difference in the PHA formed by the two recombinants: JMU194(pBTC2) accumulated 15% PHA, while JMU193(pBTC2) produced only 5% PHA after 36 h of cultivation. Furthermore, the PHA formed by E. coli JMU194(pBTC2) contained significantly more C6 and C10 monomers than did the PHA produced by JMU193(pBTC2) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

PHAs produced by E. coli recombinants grown in the presence of hexadecanoate.

| Straina | Genotype | Rate of monomer incorporation into PHAb (nmol/mg of cdw/min) | PHA%c (wt/wt) | Monomer compositiond (mol%)

|

Mwe (g/mol) | Mw/Mne | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6 | C8 | C10 | ||||||||||

| JMU193(pVLT35, pET901) | phbB+ | ≤0.1 | ≤0.1 | |||||||||

| JMU193(pBTC2, pCK01) | phaC2+ | 9 ± 3 | 5 ± 0.5 | 11 | 76 | 13 | 59,800 | 2.14 | 198 | −33.8 | 55.1 | 9.31 |

| JMU193(pBTC2, pET901) | phaC2+ phbB+ | 12 ± 4 | 6 ± 0.4 | 10 | 76 | 14 | 61,200 | 2.10 | 205 | −33.3 | 55.8 | 9.37 |

| JMU194(pVLT35, pET901) | phbB+ | ≤0.1 | ≤0.1 | |||||||||

| JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) | phaC2+ | 60 ± 10 | 15 ± 4 | 20 | 57 | 23 | 71,300 | 3.03 | 165 | −32.7 | 53.9 | 9.22 |

| JMU194(pBTC2, pET901) | phaC2+ phbB+ | 50 ± 8 | 20 ± 5 | 42 | 38 | 20 | 97,000 and 1,100,000g | 1.80g | 405 | −30.1 | ∼h | ∼h |

The recombinants were grown in 0.1NE2 minimal medium with 0.2% yeast extract and 2 mM hexadecanoate. Cells were induced with 200 μM IPTG at early exponential phase. Isolation of PHA and analysis of the PHA molecular weight and thermal properties were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Average data of three independent experiments are given.

The monomer incorporation rate was assayed at 36 h by a pulse of 0.5 mM pentadecanoate for 1.5 h as described in Materials and Methods.

The amount of PHA is given as a weight percentage (average ± the standard deviation) of the cdw.

The monomer composition is given as a molar percentage. C6, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; C8, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; C10, 3-hydroxydecanoate.

Mw, weight average molecular weight; Mn, number average molecular weight; Mw/Mn, polydispersity.

The PD was calculated based on Mn and the monomer composition.

This sample shows two peaks as indicated in Fig. 3. Mw/Mn refers to the low molecular weight peak.

∼, No melting point.

Redirecting of ketoacyl-CoA intermediates from β-oxidation into the mcl-PHA synthetic pathway in E. coli JMU193 and JMU194 recombinants.

As illustrated in Fig. 1C, it might be possible to redirect the carbon flux from the β-oxidation pathway to mcl-PHA synthesis by blocking step 8 to accumulate 3-ketoacyl-CoA intermediates and amplifying step 7 to permit the reduction of these intermediates to R-(−)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA. It is known that the ketoacyl-CoA reductase encoded by phbB of R. eutropha (step 11 in Fig. 1A) has a substrate range of C4 to C6 acyl-CoAs (12), permitting it to convert ketohexyl-CoA to R-(−)-3-hydroxyhexyl-CoA, which might be channeled into mcl-PHA by PHA polymerase.

Therefore, plasmid pET901, which contains phbB of R. eutropha, was constructed (Fig. 2B) and was subsequently introduced into E. coli recombinants JMU193(pBTC2) and JMU194(pBTC2). Ketoacyl-CoA reductase activities of 0.71 and 0.64 U/mg of total protein were found for JMU193 and JMU194 recombinants, respectively, which could result in an alteration in the intermediate concentrations of the β-oxidation cycle in these recombinants.

The effect of addition of pET901 on the characteristics of the PHA formed by JMU193 recombinants was slight. When hexadecanoate was supplied, with IPTG-induced phaC2 and phbB expression, JMU193(pBTC2, pET901) produced 6% PHA, similar to the 5% PHA seen for JMU193(pBTC2, pCK01), and the expression of phbB in JMU193(pBTC2, pET901) hardly changed the PHA composition compared to JMU193(pBTC2, pCK01) (Table 2).

The results for JMU194(pBTC2, pET901), which synthesized PHA to 20%, were more interesting. Not only did this recombinant produce more PHA than the closely related strain JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) (15% PHA), but it also produced a hexanoate-rich PHA. The higher PHA content can be attributed to different precursor concentrations since the monomer incorporation rates of the polymerase in both JMU194 recombinants were similar (Table 2). The increased hexanoate content, with a C6:C8:C10 ratio that changed from 20:57:23 to 42:38:20 in JMU194(pBTC2, pET901) clearly depended on the expression of phbB (Table 2). To verify that this change was not caused by the accumulation of free C6 monomers in the PHA samples, we also tested E. coli recombinants carrying only PhbB (pET901) and no PHA polymerase (with just pVLT35). Table 2 shows that no PHA and no C6 monomers were detected in either the JMU194 or JMU193 recombinants.

Heptadecanoate was also tested to determine whether the presence of PhbB led to PHAs with different monomer compositions. This was not the case: no significant difference was observed in the content and composition of PHAs produced by JMU194(pBTC2, pET901) and JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01). As expected, when the acyl source was heptadecanoate, JMU193(pBTC2, pCK01) and JMU193(pBTC2, pET901) again synthesized PHA with a similar monomer composition.

Physical properties of polymers produced by E. coli recombinants.

PHAs produced by the E. coli recombinants used in this study were isolated by complete solvent extraction from lyophilized cells. The monomer compositions of the purified PHAs were essentially identical to the values estimated by gas chromatography analysis after methanolysis of whole cells.

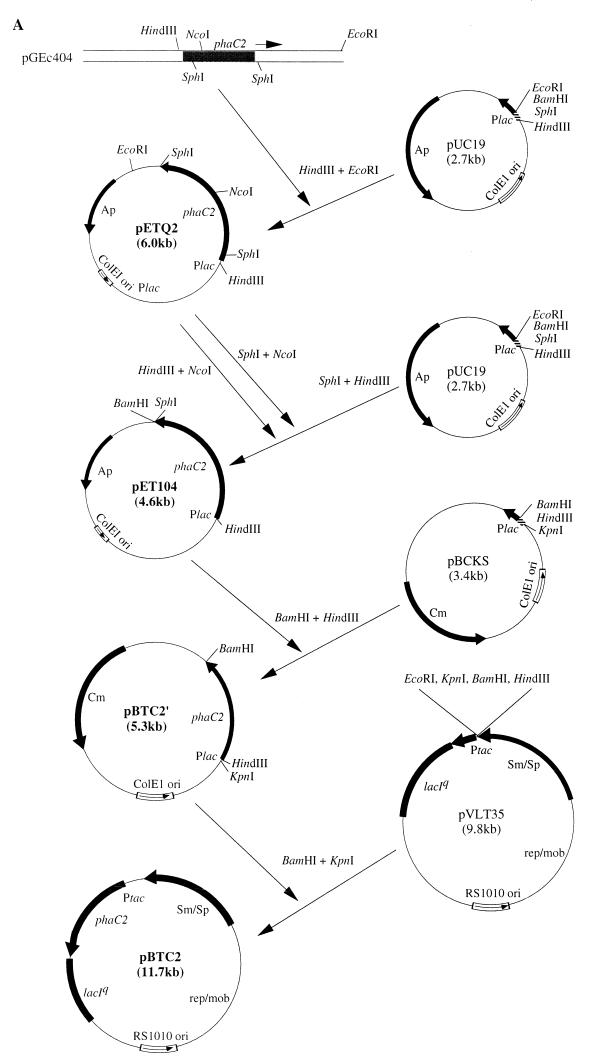

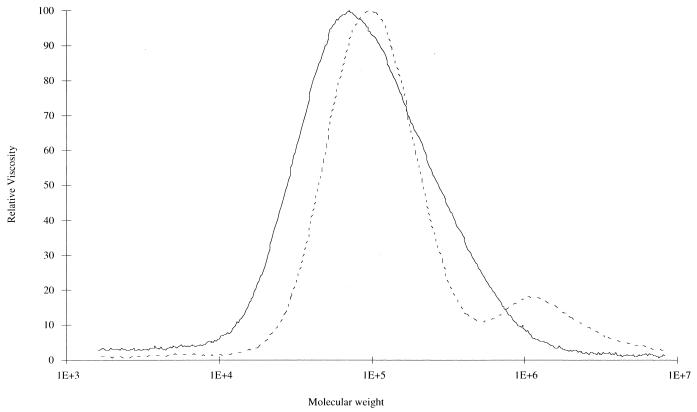

PHAs synthesized by JMU193(pBTC2, pCK01) and JMU193(pBTC2, pET901) had similar compositions, and their molecular weights and polymerization degree (PD) were also similar (Table 2). The PHA isolated from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) had a molecular weight of about 70,000, whereas JMU194(pBTC2, pET901) formed a polymer with two molecular weight peaks at about 1,100,000 and about 97,000 (Fig. 3, Table 2). Furthermore, the PD for PHA with molecular weight at 97,000 was almost 2.5-fold higher than that for PHA synthesized by JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Molecular weight of polymer isolated from JMU194 recombinants. E. coli JMU194 recombinants were grown in 0.1NE2 minimal medium with 0.2% yeast extract and 2 mM hexadecanoate. Cells were induced with 200 μM IPTG in the early exponential phase and harvested in the stationary phase. PHA was isolated from cells and analyzed by gel permeation chromatography for the molecular weight as described in Materials and Methods. Solid line, PHA from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01); dashed line, PHA from JMU194(pBTC2, pET901).

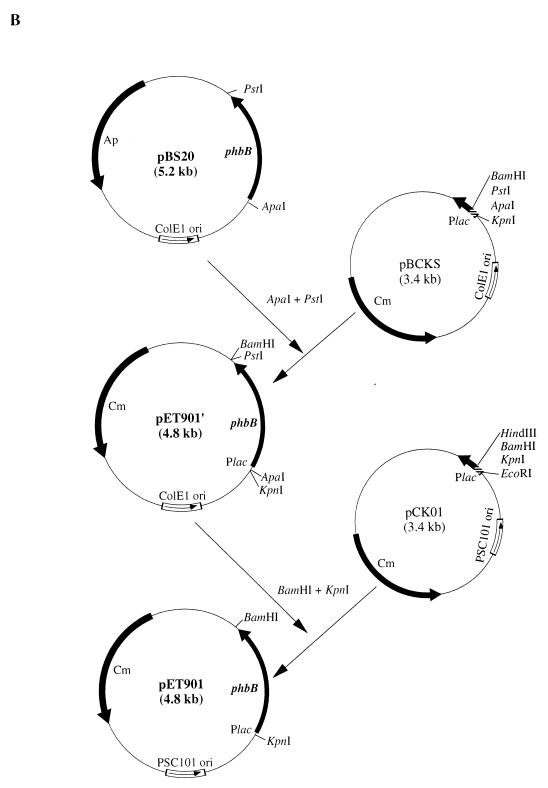

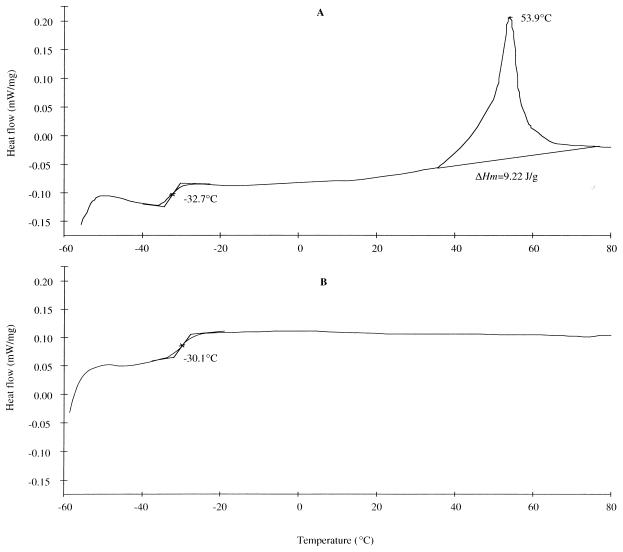

The PHAs produced from JMU193(pBTC2, pCK01) and JMU193(pBTC2, pET901) showed a similar melting point (Tm), endotherm (ΔHm), and glass transition temperature (Tg) (Table 2), whereas PHAs from two JMU194 recombinants exhibited a different DSC pattern: the PHAs isolated from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) showed Tm and ΔHm, while the PHAs isolated from JMU194(pBTC2, pET901), which contained an active PHB acetoacyl-CoA reductase, did not show a melting endotherm (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Furthermore, this PHA exhibited a Tg value that was about 2.6°C higher than that for PHA from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

DSC thermograms of the PHA samples from JMU194 recombinants. The PHA samples described in Fig. 3 were analyzed for thermal properties as described in Materials and Methods. (A) PHA from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01). (B) PHA from JMU194(pBTC2, pET901).

DISCUSSION

The monomer composition of PHAs can affect the properties of the polymer (41). The development of mcl-PHA variants depends, therefore, on the range of monomers that can be incorporated into PHA. Consequently, it is of interest to attempt to control rationally the monomer composition of new mcl-PHAs. This requires a better understanding of pathways involved in mcl-PHA synthesis and of the basic metabolic pathways that may provide PHA precursors. In this study, we set out to address two questions. One was whether ketoacyl-CoA of the β-oxidation can serve as precursor source for PHA synthesis. The second question was how the mcl-PHA monomer composition could be modified. Among the approaches we tested, pathway engineering by amplification of one potential PHA precursor supply route gave the most promising result. Other approaches, such as varying the substrates, did not lead to significant changes in PHA composition or physical properties (Table 2).

The β-oxidation intermediate ketoacyl-CoA is a potential precursor for PHA synthesis in E. coli.

Introduction of the PHA polymerase into E. coli results in utilization of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA precursors for the synthesis of PHA (29, 31, 34, 36). As illustrated in Fig. 1, when the β-oxidation is blocked at the last step (ketothiolase [FadA]), all upstream intermediates will accumulate (Fig. 1C). 3-Ketoacyl-CoA could be reduced to R-(−)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA through a 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase (step 7), S-(+)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA may be epimerized (step 6, fadB), and enoyl-CoA may be hydrated to the corresponding R-(−)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA (step 3, fadB). When the β-oxidation is blocked at step 5, catalyzed by 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (FadB), one of these possible mcl-PHA precursors, 3-ketoacyl-CoA, will not accumulate (Fig. 1B). In this study, we found that E. coli JMU194 (fadR fadA) phaC+ recombinant incorporated more C6 and C10 monomers into PHAs than the JMU193 (fadR fadB) phaC+ recombinant under the same growth conditions (Tables 1 and 2). The relative monomer content of PHA depends on the precursor concentration and the specificity of the PHA polymerase for each precursor. Since the specificity profile of the PHA polymerase is presumably identical in both recombinants, differing PHA compositions must reflect the differences in relative intracellular precursor concentrations.

When the JMU193 (fadR fadB) phaC+ recombinant is provided with phbB (amplifying step 7 in Fig. 1B by using a PHB acetoacetyl-CoA reductase, step 11 in Fig. 1A), the polymer composition did not change very much compared with the strain carrying only phaC (Table 2). This is probably due to the fact that 3-ketoacyl-CoA cannot be accumulated in this strain due to the fadB mutation, as described above. This also explains why there was no increase in the PHA content in the JMU193 (fadR fadB) phaC+ recombinant after introduction of phbB (Table 2). Since fadB-negative E. coli strains carrying phaC are able to accumulate PHA even without this ketoacyl-CoA precursor route, there must be other precursor sources, such as enoyl-CoAs of β-oxidation as described previously (7–9), which are available for PHA synthesis in E. coli.

In contrast, introduction of phbB into the JMU194 (fadR fadA) phaC+ recombinant (Fig. 1C) resulted in increased PHA accumulation and a PHA which contained twofold-higher C6 monomer than the PHA from the fadR fadA recombinant carrying only phaC (Table 2). This is compatible with the notion that in the JMU194 (fadR fadA) phaC+ recombinant there was accumulation of C6 ketoacyl-CoA, which was then reduced by the PHB acetoacyl-CoA reductase and incorporated into mcl-PHA. These data strongly indicate that the 3-ketoacyl-CoA intermediate of the β-oxidation is a potential precursor source for PHA synthesis.

When grown on heptadecanoate, no C5 monomers were found in the PHAs of E. coli fadR fadA strains carrying phaC and phbB (Table 2), although 3-hydroxypentanoyl-CoA (C5) could in principle be formed via β-oxidation from the intermediate 3-ketopentanoyl-CoA by the PHB acetoacyl-CoA reductase. This is probably due to the low affinity of the PHA polymerase for C5 monomers (15), resulting in limited incorporation into PHA.

Physical properties of PHA can be changed by pathway engineering.

We found significant differences in the physical properties of PHA isolated from fadR fadA E. coli JMU194 carrying phaC and from the same recombinant carrying additional phbB (Table 2).

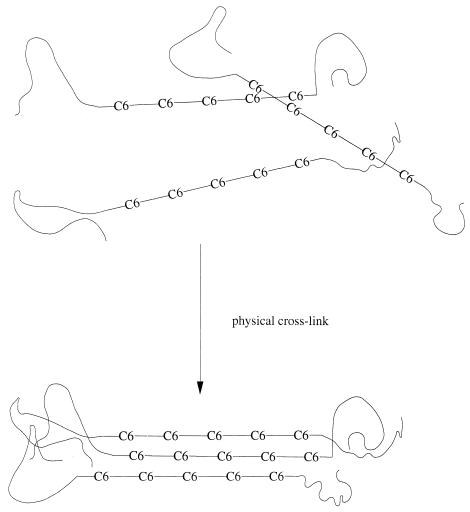

E. coli JMU194 carrying phaC accumulated PHA with a molecular weight of about 70,000. After introduction and expression of the phbB gene, PHA with two molecular weight ranges was found (Fig. 3). This is probably not caused by formation of different groups of polymers (e.g., one group is mcl-PHA, another is poly-3-hydroxyhexanoate), since only one glass transition temperature was observed (Fig. 4) and, furthermore, only one functional polymerase was introduced into the recombinant. The most likely reason for the formation of the high-molecular-weight peak is changes in the polymer chain length. PHB chains typically contain 7,000 to 23,000 monomers (see review [1]), which is 5- to 10-fold more than that found in mcl-PHAs (24). Perhaps the increased C6 content of JMU194 carrying phaC and phbB somehow alters the ratio of chain elongation to chain termination events, resulting in longer PHA chains, comparable to the PHB formed in R. eutropha and other PHB-producing organisms. Another possibility, however, is that the 1,100,000 peak of Fig. 3 is due not to longer polymer chains but to polymer aggregates due to the presence of stretches of C6 monomers in the PHA chains. These stretches could perhaps facilitate strong noncovalent interactions among PHA chains and thus result in the formation of microgels as shown in Fig. 5. These microgels may not be able to dissolve in tetrahydrofuran completely, resulting in the high-molecular-weight peak. Further experiments have to be carried out to distinguish between these two possibilities.

FIG. 5.

Model for the structure of PHA isolated from JMU194(pBTC2, pET901). Straight lines indicate 3-hydroxyhexanoate (C6) monomer-rich stretches; curved lines indicate stretches containing random C6, 3-hydroxyoctanoate (C8), and 3-hydroxydecanoate (C10) monomers.

The PHA isolated from JMU194 carrying phaC and phbB showed an approximately 2.5-fold-higher PD than that from JMU194 carrying only phaC (Table 2). This could be due to differences in the binding affinities of the pendant group of different PHA monomers to the PHA polymerase. Previously, it has been shown that the polymerase is located at the PHA granule interface between the hydrophilic cytoplasm and the relatively hydrophobic granules (10). Therefore, when the pendant group of a predominant monomer is shorter, the binding of the polymerase to the chain end may be stronger, leading to fewer chain transfers relative to chain propagation events. Thus, PHAs from JMU194(pBTC2, pET901) containing mostly propyl pendant groups showed higher PD than PHAs from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) containing mostly valeryl pendant groups. Similar results have been reported by Fuller and coworkers, who showed that the PD for PHA synthesized by P. oleovorans when grown on hexanaote and heptanoate was approximately twice as large as the PD for PHA which was produced when using octanoate and other longer-chain-length alkanoates (11).

No melting point was observed for PHA isolated from JMU194(pBTC2, pET901), whereas PHA from JMU194(pBTC2, pCK01) showed a Tm value of about 54°C (Fig. 4). Loss of the melting point could be due to the fact that this polymer contained predominantly n-propyl side chains, which may explain the inability of these samples to crystallize via close proximity of their main chains (possibly due to small quantities of longer side chain repeating units present in these samples), while having side chains which are too short to allow a layered packing order. Similar results were reported previously, showing that PHA produced by P. oleovorans from hexanoate and heptanoate did not have a clear melting point, whereas PHA produced from longer-chain alkanoates did (1, 11, 28).

In this study, we showed that there is more than one precursor source available in E. coli for mcl-PHA synthesis. One is, as described previously, the well-established acyl-CoA route, involving β-oxidation of fatty acids from acyl-CoA to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA via enoyl-CoA (7–9), following the β-oxidation cycle clockwise. The second, illustrated in the present study, involves an extension of the same cycle followed by formation of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA via 3-ketoacyl-CoA. By engineering the second pathway in E. coli, PHAs with altered monomer compositions were produced. Physical characterization of the isolated polymers shows that the monomer composition plays an important role in controlling the physical properties of PHAs. This suggests that it will be possible to obtain PHAs with altered properties by modifying and regulating fatty acid metabolic genes and PHA synthetic genes in E. coli. The experience gained with precursor enrichments in E. coli will undoubtedly support the development of suitable mcl-PHA-producing transgenic plants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Colussi for measuring molecular weight, D. Dennis for providing strains JMU193 and JMU194, and M. Held and K. Jung for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss Federal Office for Education and Science (BBW no. 96.0348) to Q.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballistreri A, Montaudo G, Impallomeni G, Lenz R W, Kim Y B, Fuller R C. Sequence distribution of beta-hydroxyalkanoate units with higher alkyl groups in bacterial copolyesters. Macromolecules. 1990;23:5059. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black P N, DiRusso C C. Molecular and biochemical analyses of fatty acid transport, metabolism, and gene regulation in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1210:123–145. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Lorenzo V, Eltis L, Kessler B, Timmis K N. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene. 1993;123:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiRusso C C, Nunn W D. Cloning and characterization of a gene (fadR) involved in regulation of fatty acid metabolism in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:583–588. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.583-588.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doi Y, Tamaki A, Kunioka M, Soga K. Biosynthesis of terpolyesters of 3-hydroxybutyrate, 3-hydroxyvalerate, and 5-hydroxyvalerate in Alcaligenes eutrophus from 5-chloropentanoic and pentanoic acids. Macromol Chem Rapid Commun. 1987;8:631–635. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández S, de Lorenzo V, Pérez-Martin J. Activation of the transcriptional regulator XylR of Pseudomonas putida by release of repression between functional domains. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukui T, Doi Y. Cloning and analysis of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) biosynthesis genes of Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4821–4830. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4821-4830.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukui T, Shiomi N, Doi Y. Expression and characterization of (R)-specific enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:667–673. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.667-673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukui T, Yokomizo S, Kobayashi G, Doi Y. Co-expression of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and (R)-enoyl-CoA hydratase genes of Aeromonas caviae establishes copolyester biosynthesis pathway in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;170:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerngross T U, Reilly P, Stubbe J, Sinskey A J, Peoples O P. Immunocytochemical analysis of poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) synthase in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16: localization of the synthase enzyme at the surface of the PHB granules. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5289–5293. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5289-5293.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross R A, DeMello C, Lenz R W, Brandl H, Fuller R C. Biosynthesis and characterization of poly(beta-hydroxyalkanoates) produced by Pseudomonas oleovorans. Macromolecules. 1989;22:1106–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haywood G W, Anderson A J, Chu L, Dawes E A. The role of NADH- and NADHP-linked acetoacetyl-CoA reductases in the poly-3-hydroxybutyrate synthesizing organism Alcaligenes eutrophus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;52:259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hrabak O. Industrial production of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1992;103:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huijberts G N M, de Rijk T C, de Waard P, Eggink G. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of Pseudomonas putida fatty acid metabolic routes involved in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1995;176:1661–1666. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1661-1666.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huisman G W, de Leeuw O, Eggink G, Witholt B. Synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates is a common feature of fluorescent pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1949–1954. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.1949-1954.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huisman G W, Wonink E, Meima R, Kazemier B, Terpstra P, Witholt B. Metabolism of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) (PHAs) by Pseudomonas oleovorans. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2191–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins L J, Nunn W D. Genetic and molecular characterization of the genes involved in short-chain fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: the ato system. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:42–52. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.42-52.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidwell J, Valentin H E, Dennis D. Regulated expression of the Alcaligenes eutrophus pha biosynthesis genes in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1391–1398. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1391-1398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y B, Lenz R W, Fuller R C. Preparation and characterization of poly(beta-hydroxyalkanoates) obtained from Pseudomonas oleovorans grown with mixtures of 5-phenylvaleric acid and n-alkanoic acids. Macromolecules. 1991;24:5256–5260. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lageveen R G, Huisman G W, Preusting H, Ketelaar P, Eggink G, Witholt B. Formation of polyesters by Pseudomonas oleovorans: effect of substrates on formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkenoates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2924–2932. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.2924-2932.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madison L L, Huisman G W. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:21–53. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.21-53.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nawrath C, Poirier Y, Somerville C. Targeting of the polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway to the plastids of Arabidopsis thaliana results in high levels of polymer accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12760–12764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunn W D. Two-carbon compounds and fatty acids as carbon sources. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1986. pp. 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overath P, Pauli G, Schairer H U. Fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: an inducible acyl-CoA synthetase, the mapping of old-mutations, and isolation of regulatory mutants. Eur J Biochem. 1969;7:559–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peoples O P, Sinskey A J. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Characterization of the genes encoding beta-ketothiolase and acetoacetyl-CoA reductase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15293–15297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peoples O P, Sinskey A J. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Identification and characterization of the PHB polymerase gene (phbC) J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15298–15303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirier Y, Nawrath C, Somerville C. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, a family of biodegradable plastics and elastomers, in bacteria and plants. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nbt0295-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preusting H, Nijenhuis A, Witholt B. Physical characteristics of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) and poly(3-hydroxyalkenoates) produced by Pseudomonas oleovorans grown on aliphatic hydrocarbons. Macromolecules. 1990;23:4220–4224. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qi Q, Rehm B H A, Steinbüchel A. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) in Escherichia coli expressing the PHA synthase gene phaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of PhaC1 and PhaC2. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:156–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qi Q S, Steinbüchel A, Rehm B H A. Metabolic routing towards polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli (fadR): inhibition of fatty acid beta-oxidation by acrylic acid. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;167:89–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren Q. Biosynthesis of medium chain length poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates: from Pseudomonas to Escherichia coli. Ph.D. thesis. Zürich, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhie H G, Dennis D. Role of fadR and atoC(Con) mutations in poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) synthesis in recombinant pha+Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2487–2492. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2487-2492.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schubert P, Steinbüchel A, Schlegel H G. Cloning of the Alcaligenes eutrophus genes for synthesis of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) and synthesis of PHB in E. coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5837–5847. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5837-5847.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senior P J, Dawes E A. The regulation of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate metabolism in Azotobacter beijerinckii. Biochem J. 1973;134:225–238. doi: 10.1042/bj1340225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slater S C, Voige W H, Dennis D E. Cloning and expression in E. coli of the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 poly-β-hydroxybutyrate biosynthetic pathway. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4431–4436. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4431-4436.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spratt Cloning, mapping, and expression of genes involved in the fatty acid-degradative multienzyme complex of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:535–542. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.535-542.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinbüchel A, Valentin H E. Diversity of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:219–228. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timm A, Steinbüchel A. Cloning and molecular analysis of the poly(3-hydroxyalkanoic acid) gene locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:15–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Leij F R, Witholt B. Strategies for the sustainable production of new biodegradable polyesters in plants: a review. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:222–238. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams S F, Peoples O P. Biodegradable plastics from plants. Chemtech. 1996;26:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witholt B. Method for isolating mutants overproducing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and its precursors. J Bacteriol. 1972;109:350–364. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.1.350-364.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Genes. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]