Abstract

BACKGROUND

Clear aligners have been widely used to treat malocclusions from crowding, extraction cases to orthodontic-orthognathic cases, and practitioners are exploring the border of it. For the first time, clear aligners were used to early intervene anterior cross-bite and facial asymmetry.

CASE SUMMARY

This case report described a four-year-old child presented with anterior cross-bite and facial asymmetry associated with functional mandibular shift, who had undergone a failed treatment with conventional appliances. The total treatment time was 18 weeks, and a stable outcome was obtained.

CONCLUSION

The increasing need in early treatment highlights the need for clinicians to thoroughly investigate for the patient regarding clinical manifestation as well as patient compliance. We hope that our case will be contemplated by clinicians when seeking for treatment alternatives.

Keywords: Early treatment, Three-dimensional diagnosis and treatment planning, Anterior cross-bite, Functional mandibular shift, Case report

Core Tip: The early treatment for children with anterior cross-bite and facial asymmetry has been widely accepted, while patient cooperation has remained the number one challenge for clinicians. After thorough investigation and planned, we initially applied clear aligner therapy on a four-year-old patient with anterior cross-bite and facial asymmetry. Successful outcome was achieved and remained stable in a 3-year follow-up at the age of 8 in the mix dentition phase. In this manuscript, every detail of our case was discussed.

INTRODUCTION

As a major problem of the primary dentition, anterior cross-bite affects approximately 25.29% of Chinese children, ranking third after deep overbite (33.66%) and spacing (28.34%)[1]. A study reported that 36% of subjects with anterior cross-bite exhibit functional shift[2]. Untreated anterior cross-bite could lead to an undesirable growth modification in which maxilla growth and dental development may be inhibited, which may eventually lead to severe skeletal deformity and cause aesthetic, functional, or sociopsychological problems[3]. In addition, children with untreated anterior cross-bites may have facial asymmetry due to tooth interference that may induce functional mandible displacement. If left untreated, this facial asymmetry tends to worsen, and causing an increased risk of craniomandibular disorders in adolescents and even temporomandibular symptoms[4].

Various methods have been used for primary dentition correction, such as removable transpalatal appliances with protruding finger springs, bonded resin-composite slopes and selective grinding[5,6]. These correction strategies appeal to clinicians because of their simplicity. However, there are limitations to what can be achieved. Clear aligners have been widely used to treat malocclusions from crowding and extraction cases to orthodontic-orthognathic cases[7], and practitioners are exploring the border of it. Clear aligner treatment is patient-friendly, aesthetic-oriented, and offers significant benefits over conventional appliances in terms of comfort and aesthetics, which perfectly meets the need for orthodontic treatment in children. A longer clinic visit interval and fewer emergencies of clear aligner treatment are especially valuable in the time of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic[8]. This case report aims to explore the potential use of clear aligners in deciduous dentition, which would extend the application of clear aligners.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 3-year-and-9-month-old female patient sought orthodontic treatment in her parents’ company, with a chief complaint of prominent lower anterior teeth and asymmetric face.

History of present illness

No history of present illness was reported.

History of past illness

No past illness was reported.

Personal and family history

No familial tendency of class III malocclusion was reported by the parents.

Physical examination

The patient was clinically assessed and fully investigated regarding oral hygiene, general health and medical history, which were unremarkable. No familial tendency of class III malocclusion was reported by the parents.

During clinical examination, a lateral shift of the mandible was observed. Her profile was minor concave, with protrusion of the upper and lower lips (Figure 1). The mandible could not be retracted to an edge-to-edge bite. The functional mandibular shift was detected, whereas nose-chin midpoints coincided when the mouth was wide open. No clicking sound or tenderness was detected in her temporo-mandibular joint area. Moreover, the clinical examination revealed mandibular displacement and habitual mandibular protraction with a deleterious tongue-thrust habit at rest and in speech.

Figure 1.

Pre-treatment facial and intra-oral photographs. A: Pre-treatment facial photos showing presence of facial asymmetry; B: Lateral view of right side; C: Frontal view; D: Lateral view of left side; E: Occlusal view of the maxillary arch; F: Occlusal view of the mandibular arch.

Intraoral examination revealed a primary dentition phase. Anterior spacing was observed, and the model analysis showed 6.5 mm spacing in the maxillary arch and 5.3 mm spacing in the mandibular arch. The cross-bite involved the maxillary and mandibular incisors and the upper right canine with a maximum negative overjet of 4.5 mm and a negative overbite of 1.5 mm. The lateral view revealed a slightly palatal inclination of the upper incisors and a labial inclination of the mandibular incisors. The upper dental midline aligned with the facial midline, while the lower dental midline deviated 3.5 mm toward the right. Centric occlusion examination revealed a flush terminal molar relation with cross-bites on the right side and mesial step on the left side. In addition, an obvious sharp cusp was observed on tooth 53, implying insufficient tooth wear (Figure 1).

Imaging examinations

The lateral head radiograph was not performed owing to parent’s wishes and for ethical reasons[9].

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on these findings, the diagnosis was established as primary dentition with anterior cross-bite and functional facial asymmetry.

TREATMENT

Treatment objectives

The following treatment goals were established: (1) Correct the etiological factors of habitual mandibular protraction and tongue thrusting; (2) Restore the normal inclination of the upper anterior teeth and close the spacing of the lower anterior teeth to establish a proper overbite and overjet; and (3) Improve facial aesthetics and symmetry

Treatment alternatives

Two treatment options were considered in this case. The first option was a removable appliance with protruding springs for the anterior maxillary teeth and selective grinding for the deciduous canine. The second option was using clear aligners.

Before being diagnosed in our clinic, the patient was initially treated with a removable transpalatal appliance that incorporated a bite plane and protruding springs. However, the treatment was interrupted because of discomfort. Moreover, the removable appliance is of no use for treating mandibular displacement. Additionally, the cusp of tooth 83 was tilted mesially to tooth 53, and tooth 53 slightly rotated in a mesial direction, which meant that grinding the cusps of tooth 53 was not an effective method. In this case, an Invisalign “Teen” package was chosen.

Treatment planning

Polyvinyl siloxane impressions were taken and sent to Invisalign®. Virtual planning of tooth movement in three dimensions was performed using ClinCheck® software (Align Technology, San Jose, CA, United States). The initial occlusion of this patient is shown in Figure 2A. Ellipsoid attachments were placed on the upper central incisors and the lower canines to improve retention, and rectangular attachments were placed on the occluding surfaces of the lower deciduous molars to obtain vertical clearance.

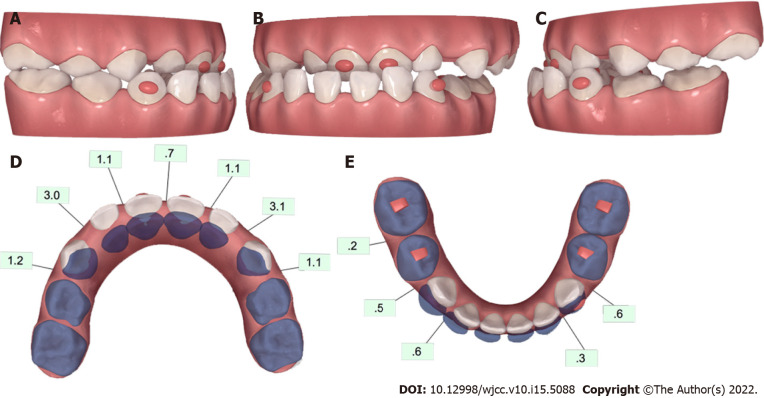

Figure 2.

Pre-treatment ClinCheck® models and ClinCheck® treatment plan. A: Lateral view of right side of pre-treatment model; B: Frontal view of pre-treatment model; C: Lateral view of left side of pre-treatment model; D: Occlusal view of superimposition of pre-treatment (blue) and post-treatment (white) maxillary arch models; E: Occlusal view of superimposition of pre-treatment (blue) and post-treatment (white) mandibular arch models.

Expansion and proclination of the upper anterior teeth were carried out first, with a small amount of intrusion and distal rotation of tooth 53 to relieve the occlusal interference. Simultaneously, the incisors were unlocked by bite attachments to seat bilateral condyles into a centric relation to solve the functional facial asymmetry. Subsequently, the upper anterior teeth were further proclined, and the lower anterior teeth were retracted to close the spacing, which could further coordinate the upper and the lower arches (Figure 2B). Meanwhile, slight extrusion of incisors was necessary to avoid the anterior open bites. Myofunctional therapies, including tongue elevation and correction of mandibular protraction habits, were performed in the process to ensure long-term stability.

Interventions

The patient was instructed to wear each aligner 22 h per day, even during school time. Nineteen aligners were scheduled, and a 5-day-change protocol was adopted because of the faster tooth movement during the deciduous dentition. A study reported that the activation force imparted by the aligner slowly decreases and plateaus within 5 d[10]. The duration of therapy was in line with conventional approaches.

A monthly follow-up was planned to monitor the wearing. During the treatment, no detachment condition was reported. No self-perceived pain, discomfort or impairment of function was reported during treatment. When the patient wore the fourth aligner, her functional facial asymmetry was corrected as expected. The midlines of both arches were coincident, followed by the cross-bite of tooth 53 resolved and reserve overjet of teeth 52-62 reduced. At the same time, the posterior cross-bite was corrected (Figure 3A). The anterior cross-bite was almost corrected in the thirteenth aligner by modifying the maxillary incisors’ torque and closing the mandibular arch's spacing (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Intraoral photographs under treatment. A: Lateral view of right side of intraoral pictures of the 4th aligner; B: Frontal view of intraoral pictures of the 4th aligner; C: Lateral view of left side of intraoral pictures of the 4th aligner; D: Lateral view of right side of intraoral pictures of the 13th aligner; E: Intraoral pictures of the 13th aligner; F: Lateral view of left side of intraoral pictures of the 13th aligner.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The total treatment time was 18 wk, and only 22 aligners were employed. The inclination of the incisors was improved to achieve an optimal overbite and overjet. Ideal canine and molar relationships and occlusion were established after correcting posterior cross-bite. The frontal smiling view revealed a coincident facial midline and the dental midline. The lateral view showed a straight profile with labially inclined upper incisors and improved facial aesthetics (Figure 4). In addition, the aberrant neuromuscular behavior of the mandible and the tongue was corrected after myofunctional therapy.

Figure 4.

Post-treatment facial and intraoral photographs of the 19th aligner. A: Post-treatment facial photos showing correction of facial asymmetry and harmonic appearance; B: Lateral view of right side; C: Frontal view showing correction of anterior cross-bite; D: Lateral view of left side; E: Occlusal view of the mandibular arch; F: Occlusal view of the maxillary arch.

At the 6-month follow-up, although there was a minor relapse of spacing in the lower arch, an ideal occlusion was kept in both arches (Figure 5). Interestingly, tooth wear of cuspid 53 was observed, suggesting the establishment of canine-guided occlusion. The facial asymmetry was improved.

Figure 5.

Intraoral photographs of a 6-month follow-up. A: Lateral view of right side; B: Frontal view; C: Lateral view of left side.

A 3-year follow-up at the age of 8 was recorded, and stability of the treatment was obtained in the mixed dentition. The permanent anterior teeth resulted in good positions, maintaining appropriate interincisal relations. An ideal symmetrical occlusion was achieved (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Facial and intraoral photographs of a 3-year follow-up. A: 3-year follow-up facial photos; B: Lateral view of right side; C: Frontal view; D: Lateral view of left side; E: Occlusal view of the mandibular arch; F: Occlusal view of the maxillary arch.

DISCUSSION

Class III malocclusion can appear early in deciduous dentition, and the deformity may vary from mild to severe throughout development. This malocclusion is often accompanied by varying degrees of mandibular deviation with few self-correction trends[11-13]. It is a mainstream perception that early intervention of class III malocclusion should begin early, at the primary dentition stage to curb the undesirable growth modifications during some of the most formative years, notwithstanding the controversy about the correct indication and stability[14,15].

The patient should be clinically assessed and fully investigated during treatment planning regarding dental, functional, profile and psycho-social correlations, oral hygiene, general health, and family history. Furthermore, there has been a lack of consideration regarding patient compliance and how it is a significant determinant of treatment outcome, especially in the treatment of young children[16].

A functional mandibular shift commonly arises from tooth interferences or a narrow maxilla[17,18]. In this case, occlusal interference caused by the insufficient wear of tooth 53 influenced the mandibular closing trajectory that forced the mandible to protrude and displace laterally, resulting in the posterior cross-bite and midline shift. Moreover, tongue habits have caused a transverse discrepancy in the arch relationship, specifically, a narrow maxilla with retroclined incisors and a mandibular arch with scattered space, facilitating anterior cross-bite. The mandibular shift from the centric relation (CR) to the intercuspal position is a key indicator diagnosing functional mandible displacement[19]. Mandibular displacement may be an expedient mechanism for postural adjustment consequent to occlusal disharmony and pain[20]. In our case, habitual asymmetric posture was observed as the midline deviation of the mandible left-deviated mandibular dental midline corrected itself as the mandible opened from a rest position. The mandibular dental midline patient widely opened her mouth from the resting position. The diagnosis of functional facial asymmetry would be more accurate after “deprogramming” the muscle memory.

Selective grinding of teeth is a simple treatment approach to correct the functional mandibular shift in the primary dentition[21]. However, it may not be favorable when the intercanine width differential is smaller than 3.3 mm or when a significant intermolar width discrepancy is detected[22]. Thus, in our case, grinding therapy may not have been satisfactory. Removable appliances are commonly used for anterior cross-bite correction. However, the discomfort was considered its main disadvantage, which would reduce treatment effectiveness and expand treatment duration, especially in young patients. Facemasks combined with auxiliaries, such as rapid palatal expanders, have also been reported for the correction of anterior cross-bites[5]. However, the lack of anchorage in deciduous dentition and the uncertainty about dental or skeletal effects limit the use of this device. In addition, side effects, including clockwise rotation of the mandible and extrusion of the molars, should not be neglected to prevent undesirable anterior open bite[23].

Compared with conventional removable or fixed appliances, clear aligners blend seamlessly with crown anatomy and thus possess the ability of three-dimensional, precise movement of the teeth. Furthermore, aligner thickness could provide adequate vertical clearance for cross-bite correction, avoiding the bulkiness of posterior capping, which could minimize traumatic occlusion or tooth wear during a cross-bite correction. Clear aligners can also prevent aesthetic drawbacks and speech impairment and can allow for optimal oral hygiene. This results in more positive patient feedback and significant improvements in children’s compliance[24].

In this case, tooth 53 was proclined with clear aligners to relieve the occlusal interference through the three-dimensional movement of intrusion and rotation. It is suggested that with more than 2/3 of vertical overbite to use bite ramps[25]. In our case, additional attachments were placed on the occlusal plane to provide vertical clearance for cross-bite correction. Subsequently, the anterior cross-bite was corrected through the expansion of the upper arch anterior teeth and the retraction of the lower anterior teeth. It is worth mentioning that because this patient had a shallow negative overbite, simple proclination of the upper anterior may cause anterior open bite and aberrant tongue-thrusting habits. Therefore, a slight extrusion of the incisors was designed to compensate. The bite block effects of aligner thickness also helped achieve better occlusal vertical control. During treatment, it was necessary to the check aligner fit at each follow-up to compensate for the poor retentive force due to the anatomically short crowns of the primary teeth. Additionally, clear aligner treatment is more efficient and effective for both patients and clinicians, with a long interval between follow-ups, fewer emergencies, or fewer negative side effects, especially in the unprecedented and unpredictable time of the pandemic[26].

CONCLUSION

This case reported the effectiveness of clear aligners in correcting anterior cross-bite and facial asymmetry in the primary dentition, obtaining a satisfactory and long-term stable outcome. Clear aligner therapy shows great potential in early intervention for deciduous teeth malocclusion due to its accurate three-dimensional tooth movement control, low cariogenic rate, and high coordination of children, which provides a new way to correct complicated cases of deciduous dentition. As encouraging results were achieved, the application of clear aligners might be limited under a thorough evaluation of benefits and burden. Further investigations are needed to standardize the treatment protocol.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 17, 2021

First decision: February 8, 2022

Article in press: March 26, 2022

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arumugam EAP, India; Kar SK, India; Sukumaran A, Qatar S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Yi-Ran Zou, State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Orthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China.

Zi-Qi Gan, Department of Orthodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Guangzhou 510055, Guangdong Province, China.

Li-Xing Zhao, State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Orthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China. zhaolixing@scu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Shen L, He F, Zhang C, Jiang H, Wang J. Prevalence of malocclusion in primary dentition in mainland China, 1988-2017: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4716. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22900-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thilander B, Myrberg N. The prevalence of malocclusion in Swedish schoolchildren. Scand J Dent Res. 1973;81:12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1973.tb01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simões WA. Selective grinding and Planas' direct tracks as a source of prevention. J Pedod. 1981;5:298–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinto AS, Buschang PH, Throckmorton GS, Chen P. Morphological and positional asymmetries of young children with functional unilateral posterior crossbite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:513–520. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.118627a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira da Silva HCF, de Paiva JB, Rino Neto J. Anterior crossbite treatment in the primary dentition: Three case reports. Int Orthod. 2018;16:514–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ortho.2018.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devasya A, K Ramagoni N, Taranath M, Ev Prasad K, Sarpangala M. Acrylic Planas Direct Tracks for Anterior Crossbite Correction in Primary Dentition. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;10:399–403. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weir T. Clear aligners in orthodontic treatment. Aust Dent J. 2017;62 Suppl 1:58–62. doi: 10.1111/adj.12480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turkistani KA. Precautions and recommendations for orthodontic settings during the COVID-19 outbreak: A review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willis CE, Slovis TL. The ALARA concept in pediatric CR and DR: dose reduction in pediatric radiographic exams--a white paper conference. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:373–374. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Ren C, Wang Z, Zhao P, Wang H, Bai Y. Changes in force associated with the amount of aligner activation and lingual bodily movement of the maxillary central incisor. Korean J Orthod. 2016;46:65–72. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2016.46.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baccetti T, Reyes BC, McNamara JA Jr. Craniofacial changes in Class III malocclusion as related to skeletal and dental maturation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:171.e1–171.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brito HHA, Mordente CM. Facial asymmetry: virtual planning to optimize treatment predictability and aesthetic results. Dental Press J Orthod. 2018;23:80–89. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.23.6.080-089.bbo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimberg L, Lennartsson B, Arnrup K, Bondemark L. Prevalence and change of malocclusions from primary to early permanent dentition: a longitudinal study. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:728–734. doi: 10.2319/080414-542.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell PM. The dilemma of Class III treatment. Early or late? Angle Orthod. 1983;53:175–191. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1983)053<0175:TDOCIT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha KS. Skeletal changes of maxillary protraction in patients exhibiting skeletal class III malocclusion: a comparison of three skeletal maturation groups. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:26–35. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073<0026:SCOMPI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Moghrabi D, Salazar FC, Pandis N, Fleming PS. Compliance with removable orthodontic appliances and adjuncts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152:17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsanidis N, Antonarakis GS, Kiliaridis S. Functional changes after early treatment of unilateral posterior cross-bite associated with mandibular shift: a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43:59–68. doi: 10.1111/joor.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy DB, Osepchook M. Unilateral posterior crossbite with mandibular shift: a review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2005;71:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evangelista K, Valladares-Neto J, Garcia Silva MA, Soares Cevidanes LH, de Oliveira Ruellas AC. Three-dimensional assessment of mandibular asymmetry in skeletal Class I and unilateral crossbite malocclusion in 3 different age groups. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martín C, Palma JC, Alamán JM, Lopez-Quiñones JM, Alarcón JA. Longitudinal evaluation of sEMG of masticatory muscles and kinematics of mandible changes in children treated for unilateral cross-bite. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma DS, Srivastava S, Tandon S. Preventive orthodontic approach for functional mandibular shift in early mixed dentition: A case report. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2019;9:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindner A. Longitudinal study on the effect of early interceptive treatment in 4-year-old children with unilateral cross-bite. Scand J Dent Res. 1989;97:432–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1989.tb01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adobes Martin M, Lipani E, Alvarado Lorenzo A, Bernes Martinez L, Aiuto R, Dioguardi M, Re D, Paglia L, Garcovich D. The effect of maxillary protraction, with or without rapid palatal expansion, on airway dimensions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2020;21:262–270. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2020.21.04.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alajmi S, Shaban A, Al-Azemi R. Comparison of Short-Term Oral Impacts Experienced by Patients Treated with Invisalign or Conventional Fixed Orthodontic Appliances. Med Princ Pract. 2020;29:382–388. doi: 10.1159/000505459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee BD. Correction of crossbite. Dent Clin North Am. 1978;22:647–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seligman LD, Hovey JD, Chacon K, Ollendick TH. Dental anxiety: An understudied problem in youth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;55:25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]