Abstract

Background

Healthy sleep is an important component of childhood development. Changes in sleep architecture, including sleep stage composition, quantity, and quality from infancy to adolescence are a reflection of neurologic maturation. Hospital admission for acute illness introduces modifiable risk factors for sleep disruption that may negatively affect active brain development during a period of illness and recovery. Thus, it is important to examine non‐pharmacologic interventions for sleep promotion in the pediatric inpatient setting.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of non‐pharmacological sleep promotion interventions in hospitalized children and adolescents on sleep quality and sleep duration, child or parent satisfaction, cost‐effectiveness, delirium incidence, length of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, and mortality.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, three other databases, and three trials registers to December 2021. We searched Google Scholar, and two websites, handsearched conference abstracts, and checked reference lists of included studies.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs, including cross‐over trials, investigating the effects of any non‐pharmacological sleep promotion intervention on the sleep quality or sleep duration (or both) of children aged 1 month to 18 years in the pediatric inpatient setting (intensive care unit [ICU] or general ward setting).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial eligibility, evaluated risk of bias, extracted and synthesized data, and used the GRADE approach to assess certainty of evidence. The primary outcomes were changes in both objective and subjective validated measures of sleep in children; secondary outcomes were child and parent satisfaction, cost‐effectiveness ratios, delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at time of hospital discharge, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, and mortality.

Main results

We included 10 trials (528 participants; aged 3 to 22 years) in inpatient pediatric settings. Seven studies were conducted in the USA, two in Canada, and one in Brazil. Eight studies were funded by government, charity, or foundation grants. Two provided no information on funding.

Eight studies investigated behavioral interventions (massage, touch therapy, and bedtime stories); two investigated physical activity interventions. Duration and timing of interventions varied widely. All studies were at high risk of performance bias due to the nature of the intervention, as participants, parents, and staff could not be masked to group assignment.

We were unable to perform a quantitative synthesis due to substantial clinical heterogeneity.

Behavioral interventions versus usual care

Five studies (145 participants) provided low‐certainty evidence of no clear difference between multicomponent relaxation interventions and usual care on objective sleep measures. Overall, evidence from single studies found no clear differences in daytime or nighttime sleep measures (33 participants); any sleep parameter (48 participants); or daytime or nighttime sleep or nighttime arousals (20 participants). One study (34 participants) reported no effect of massage on nighttime sleep, sleep efficiency (SE), wake after sleep onset (WASO), or total sleep time (TST) in adolescents with cancer. Evidence from a cross‐over study in 10 children with burns suggested touch therapy may increase TST (391 minutes, interquartile range [IQR] 251 to 467 versus 331 minutes, IQR 268 to 373; P = 0.02); SE (76, IQR 53 to 90 versus 66, IQR 55 to 78; P = 0.04); and the number of rapid eye movement (REM) periods (4.5, IQR 2 to 5 versus 3.5, IQR 2 to 4; P = 0.03); but not WASO, sleep latency (SL), total duration of REM, or per cent of slow wave sleep.

Four studies (232 participants) provided very low‐certainty evidence on subjective measures of sleep. Evidence from single studies found that sleep efficiency may increase, and the percentage of nighttime wakefulness may decrease more over a five‐day period following a massage than usual care (72 participants). One study (48 participants) reported an improvement in Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire scores after discharge in children who received a multicomponent relaxation intervention compared to usual care. In another study, mean sleep duration per sleep episode was longer (23 minutes versus 15 minutes), and time to fall asleep was shorter (22 minutes versus 27 minutes) following a bedtime story versus no story (18 participants); and children listening to a parent‐recorded story had longer SL than when a parent was present (mean 57.5 versus 43.5 minutes); both groups reported longer SL than groups who had a stranger‐recorded story, and those who had no story and absent parents (94 participants; P < 0.001).

In one study (34 participants), 87% (13/15) of participants felt they slept better following massage, with most parents (92%; 11/12) reporting they wanted their child to receive a massage again. Another study (20 participants) reported that parents thought the music, touch, and reading components of the intervention were acceptable, feasible, and had positive effects on their children (very low‐certainty evidence).

Physical activity interventions versus usual care

One study (29 participants) found that an enhanced physical activity intervention may result in little or no improvement in TST or SE compared to usual care (low‐certainty evidence). Another study (139 participants), comparing play versus no play found inconsistent results on subjective measures of sleep across different ages (TST was 49% higher for the no play groups in 4‐ to 7‐year olds, 10% higher in 7‐ to 11‐year olds, and 22% higher in 11‐ to 14‐year olds). This study also found inconsistent results between boys and girls (girls in the first two age groups in the play group slept more than the no play group).

No study evaluated child or parent satisfaction for behavioral interventions, or cost‐effectiveness, delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at hospital discharge, length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, or mortality for either behavioral or physical activity intervention.

Authors' conclusions

The included studies were heterogeneous, so we could not quantitatively synthesize the results. Our narrative summary found inconsistent, low to very low‐certainty evidence. Therefore, we are unable to determine how non‐pharmacologic sleep promotion interventions affect sleep quality or sleep duration compared with usual care or other interventions.

The evidence base should be strengthened through design and conduct of randomized trials, which use validated and highly reliable sleep assessment tools, including objective measures, such as polysomnography and actigraphy.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Female; Humans; Male; Child, Hospitalized; Delirium; Delirium/prevention & control; Intensive Care Units; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Respiration, Artificial; Sleep

Plain language summary

Methods for promoting sleep in children and young people in hospital without using medicines (non‐medicinal)

Key messages

We are uncertain how effective non‐medicinal sleep promotion methods are for children and young people in hospital.

Studies that use established, reliable research methods are needed to investigate non‐medicinal sleep promotion in hospitalized children and young people, to identify methods that work.

Why is sleep important for children in hospital?

Sleep is an important part of healthy childhood development and helps to keep children healthy. Sleep patterns change throughout childhood, as children’s brains develop. When children are ill and stay in hospital, their sleep may be of poor quality, or disrupted by the constant noise and light, medical treatments, monitoring by nurses, stress, and pain.

While medicines can be used to try to improve sleep in hospitalized children, studies show they do not work particularly well, and can make the quality of sleep worse. Non‐medicinal ways of promoting sleep can be used instead. These may include changes to the hospital environment, music, massage, or other methods.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out whether non‐medicinal ways of trying to improve sleep work better than usual care or other methods in hospitalized children.

We wanted to look at how well these different methods worked on:

‐ the quality and quantity of sleep in the children;

‐ child and parent satisfaction;

‐ length of time for which breathing was supported by a ventilator (ventilator support);

‐ delirium;

‐ cost‐effectiveness;

‐ length of hospital stay; and

‐ mortality.

We also wanted to find out if non‐medicinal methods were associated with any unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We looked for studies that compared non‐medicinal methods for improving sleep with usual care, or other methods in children in hospital.

We compared and summarized the results of the studies, and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors, such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 10 trials from three countries, which involved 528 children and young people (aged from 4 to 22 years). Eight studies were funded by non‐profit organizations or government sources.

All the children and young people were staying in hospital for more than 48 hours on regular wards, or in children’s intensive care units. The methods used to try to improve sleep included behavioral interventions (relaxation, including music, reading, and quiet time; touch therapy, and massage), and physical activity interventions.

There were many differences between studies in the participants, the methods used to measure the quantity and quality of sleep, and the way the results were analyzed. As a result, we could not combine the findings of trials that investigated similar methods; instead, we provided a descriptive summary.

Behavioral interventions

Studies that combined methods of relaxation found that these may make little or no difference on the amount or quality of sleep compared to usual care.

Touch therapy may improve total sleep time and sleep quality in children with burns. Massage and bedtime stories may also improve sleep. However, we have little confidence in these results, because of differences in the study populations and the measurement methods they used.

Children and parents may be satisfied with both massage and multicomponent relaxation methods for improving sleep. However, we are not confident about this result, as the people in the studies knew which sleep‐improving method they received, and there were not enough studies for us to be certain about their results.

We did not identify any studies that reported length of ventilator support, delirium, cost‐effectiveness, length of hospital stay, or mortality.

Physical activity interventions

One study showed that using a stationary (exercise) bicycle to improve sleep may not improve total sleep time or quality of sleep compared to usual care. Another study investigated whether organized play improved sleep; it found inconsistent results for boys and girls, and for children in different age groups. No study evaluated child or parent satisfaction, cost‐effectiveness, delirium, length of ventilator support, length of hospital stay, or mortality.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We did not identify any studies that reported the effects of complementary interventions, such as aromatherapy, acupressure, or acupuncture.

We did not identify any studies for any intervention that reported length of ventilator support, delirium, cost‐effectiveness, length of hospital stay, or mortality.

We are not confident in any of these results; it is possible that these results would change if we had more evidence.

How up to date is this review?

This evidence is current to December 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Behavioral interventions versus usual care for sleep promotion in pediatric inpatients.

|

Patient or population: children between the ages of 1 month and 18 years who were admitted to a pediatric inpatient setting from another location Settings: pediatric inpatient ward or intensive care unit Interventions: multicomponent relaxation interventions, massage, healing touch, bedtime stories Comparison: usual care | ||||

| Outcomes | Impact |

Number of participants (studies)* |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Objective measures of sleep Measured with: TST (min), SE (%), SL (min), WASO (min) Timing of assessment: during hospitalization |

|

145 (5 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Mean age 10.1 years (range 4 to 22 years) |

|

Subjective sleep quality or quantity Measured with: video, questionnaire, or observation scale Timing of assessment: during hospitalization (3 studies) and after hospital discharge (1 study) |

|

232 (4 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝

Very lowb |

Mean age not provided for all studies (range 3 to 18 years) |

|

Participant or parent satisfaction Measured with: surveys Timing of assessment: during hospitalization |

|

54 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | Mean age 12.6 years (range not available) |

| Cost‐effectiveness | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at hospital discharge | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Length of mechanical ventilation | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Length of hospital stay | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| CSHQ: Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire; ICU: intensive care unit; min: minutes; PICU: pediatric ICU; REM: rapid eye movement; SE: sleep efficiency; SL: sleep latency; TST: total sleep time; vs: versus; WASO: wake after sleep onset | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

aDowngraded two levels due inconsistency (differences in population and differences in interventions) bDowngraded two levels due to risk of bias (high risk of bias from inability to blind outcome assessors for this outcome), and one level due to inconsistency (differences in intervention and population) cDowngraded two levels for imprecision (small sample size and inadequate data [small number of included studies; only two trials identified for comparison]); and one level for risk of bias (lack of blinding)

Summary of findings 2. Physical activity interventions versus usual care for sleep promotion in pediatric inpatients.

|

Patient or population: children between the ages of 1 month and 18 years who were admitted to a pediatric inpatient setting from another location Settings: pediatric inpatient ward or intensive care unit Intervention: early physical activity intervention (stationary bicycle‐style exerciser) and play Comparison: usual care | ||||

| Outcomes | Impact | Number of participants (studies)* | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Objective measures of sleep Measured with: TST (min), SE (%) Timing of assessment: days 0 to 3 |

One study compared the effect of an enhanced physical activity intervention, using a stationary bicycle‐style exerciser vs standard care using actigraphy. There was no evidence of a difference in SE or TST between the groups. | 29 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Mean age 12.5 years (range 7.4 to 18.2) |

|

Subjective sleep quality or quantity Measured with: sleep logs (observation) Timing of assessment: during hospitalization |

One study compared the effect of play activities vs no play on sleep in children hospitalized for respiratory disease, using sleep logs. TST was 49% higher for the non‐play groups in 4 to 7 year olds compared to play groups, 10% higher in 7 to 11 year olds and 22% higher in 11 to 14 year olds. Girls in the first two age groups slept more in the play group. | 139 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝

Very Lowb |

Age range 4 to 14 years |

| Participant or parent satisfaction | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Cost‐effectiveness | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at hospital discharge | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Length of mechanical ventilation | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Length of hospital stay | None of the included studies provided data on this outcome. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Min: minutes; SE: sleep efficiency; TST: total sleep time; vs: versus | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

aDowngraded two levels due to imprecision (small sample size) bDowngraded two levels for high risk of bias (6/7 domains unclear or high risk of bias), and one level for imprecision (inadequate data due to small number of included studies)

Background

Description of the condition

Sleep is a basic human need. The process of rest and restoration occurs during the natural suspension of consciousness that occurs during sleep (Kryger 2005; Kudchadkar 2009; Kudchadkar 2014a; Kudchadkar 2014b; Murali 2003). Sleep is not a passive process, but one that is characterized by dynamic physiological changes. While the function of sleep remains elusive, the physiological effects and consequences of altered sleep can impact multiple systems throughout the body (Kudchadkar 2014a).

It is well known that sleep needs are in a constant state of change as a child matures from the neonatal to adolescent period, reflecting brain maturation (Feinberg 2013). During recovery from illness, children admitted to the hospital are exposed to a multitude of risk factors for sleep disruption, including noise, pain, anxiety, medications, interruptions for nursing care, and invasive medical interventions. Studies that used both objective and subjective assessment tools have demonstrated severe sleep disruption in hospitalized children (Cook 2020; Cureton‐Lane 1997a; Erondu 2019; Hinds 2007; Kudchadkar 2014a; Kudchadkar 2016c; Meltzer 2012). Sleep disruption occurs at a time when recovery and healing are the goal, potentially interferes with fundamental physiological processes, and can lead to increased energy release, impaired immunity, and delirium (Barnes 2016; Kamdar 2015). In addition, sleep disturbances from infancy through adolescence are associated with changes in brain morphology, and worsened short‐ and long‐term neurocognitive outcomes (Cheung 2017; Kocevska 2017; Saré 2016).

Although there are proven, inexpensive, and non‐invasive modalities to promote sleep, such methods are rarely used for children in the hospital setting (Kudchadkar 2014b). A recent systematic review of the literature surrounding sleep in the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU) found only nine, mostly observational, studies that investigated the quality of sleep in critically ill children (Kudchadkar 2014a). All the studies demonstrated significant sleep fragmentation and decreases in slow‐wave sleep. Slow‐wave sleep is the most restorative aspect of sleep, and an integral component of cognitive maturation during childhood and adolescence (Kudchadkar 2014a). In the hospital floor setting, sleep disturbance due to noise, pain, vital sign checks, and anxiety is associated with increased night awakenings and longer sleep latency (time to sleep onset [Meltzer 2012]). Among children recovering from major surgery, approximately 40% demonstrate no identifiable difference between nighttime and daytime activity levels, measured by actigraphy, suggesting significant circadian rhythm (sleep‐wake cycle) disturbance (Kudchadkar 2016b). Sleep promotion is not a priority in hospital culture, despite increasing evidence in the literature that sleep loss and fragmentation in critically‐ill adults increase the risk of delirium, which is an important risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality (Pandharipande 2006; Smith 2011). A recent Cochrane Review summarized the available evidence for non‐pharmacological interventions to promote sleep in critically ill adults admitted to the ICU (Hu 2015). Another systematic review summarized evidence on the effectiveness of non‐pharmacologic interventions for preterm infants in the neonatal ICU (Liao 2018a). However, the role of non‐pharmacological interventions for children and adolescents in other pediatric inpatient settings has not been synthesized.

Hospitals across the country are noisy, brightly lit environments, where care providers undertake multiple interventions throughout the day and night to assist children’s recovery. Few hospitals use noise reduction strategies to target World Health Organization (WHO) recommended levels (less than 30 A‐weighted decibels [dBA] for day and nighttime), and the current literature demonstrates that ICU noise levels are often greater than 50 dBA, regardless of the time of day, with several intermittent peaks that exceed 80 dBA (Busch‐Vishniac 2005; Kudchadkar 2014b; Liu 2005). In addition, a lack of natural sunlight and abolished patterns of normal light‐dark exposure is common in the hospital setting, with adverse effects on sleep architecture (the basic structural organization of normal sleep) and circadian rhythms (Glotzbach 1993; Kudchadkar 2016a). A 2007 study showed that 6% of all hospitalized children are prescribed medications to promote sleep, which can include opioids, benzodiazepines, and diphenhydramine (Meltzer 2007). Although these pharmacologic agents may decrease the time to sleep onset, they can significantly impact sleep architecture and lead to increased sleep fragmentation (Kudchadkar 2009).

Description of the intervention

Given the adverse effects of sedatives and analgesics on sleep physiology, the use of non‐pharmacological interventions has been explored in hospitalized adults, primarily in the ICU environment (Hu 2015; Kamdar 2014), and infants in the neonatal ICU (NICU [Liao 2018a]). These interventions can be categorized as: (1) environmental (noise and lighting modification; (2) behavioral (massage, music therapy, guided imagery); and (3) physical therapy interventions (mobility and exercise during the day to improve sleep at night [Kamdar 2016; Saliski 2015]). Possible environmental interventions include: earplugs, alarm modifications, headphones, white noise, or unit‐based 'quiet hours' (Foreman 2015; Freedman 2001; Hu 2015; Walder 2000), cycled lighting, and bright light therapy (Simons 2016; Taguchi 2007). Behavioral and complementary interventions that have been investigated in hospitalized adults include massage, aromatherapy, acupressure, and relaxation interventions, including music therapy and guided imagery (Richards 1998; Richardson 2003). All of these modalities have potential applications for the pediatric population, with the addition of kangaroo care (method of holding an infant that involves skin‐to‐skin contact) in the NICU setting (Baley 2015). Although potential pharmacological therapies, such as melatonin and atypical antipsychotic medications, are increasingly being used in the pediatric hospital setting with a goal of sleep promotion or delirium prevention (or both), the short‐ and long‐term effects of these agents are not well studied in the developing brain. Therefore, a focus on non‐invasive, low‐risk interventions is needed to promote sleep in hospitalized children undergoing active neurocognitive development.

How the intervention might work

There is a growing body of literature supporting the effectiveness of non‐pharmacological interventions in promoting sleep in hospitalized adults (Kamdar 2014; Koo 2008; Richards 2003; Richardson 2007; Scotto 2009), and neonates (Abdeyazdan 2016; Almadhoob 2020; Liao 2018a). Hospitalized children and adolescents also encounter disrupted sleep, and are just as likely to experience side effects with pharmacological interventions that promote sleep. Environmental, behavioral, and physical activity interventions that promote sleep in the home environment should have similar benefits when translated to the hospital environment, with augmented effects when used in combination (Berger 2021).

Environmental interventions, including noise reduction and lighting optimization, are safe and potentially effective strategies to promote healthy sleep in children. Sudden peaks in noise levels that occur frequently in the adult ICU increase arousals from sleep, demonstrated by polysomnography, the gold‐standard test for sleep measurement (Aaron 1996). In the pediatric ICU (PICU), noise is a strong predictor of sleep state, with louder noises correlating to increased awakenings from sleep (Cureton‐Lane 1997a). Reducing the background level, as well as peak levels of noise, with noise reduction interventions decreases the likelihood of arousing a child from sleep in the hospital setting, improving sleep continuity and quality. Continuous exposure to artificial light can abolish the normal circadian rhythm and diminish the normal peak in melatonin secretion at night. Day‐night cycling of light could help normalize the circadian rhythm of hospitalized children and decrease time to sleep onset.

Behavioral interventions, such as massage and touch therapy, provide modes of relaxation to decrease stress and anxiety that is common for hospitalized infants and children, with potential to decrease time to sleep onset and improve sleep continuity and quality (Mindell 2018/08).

Physical activity interventions engage the hospitalized child in activities and exercise during the day to promote rest at night (Hopkins 2015; Wieczorek 2016).

Finally, complementary and alternative therapies, such as aromatherapy or acupuncture, may help decrease anxiety and improve pain, with improved time to sleep onset, sleep quality, and sleep continuity (Cao 2009).

Most importantly, all these interventions must be easy for caregivers to implement, and ideally, should have high compliance amongst children and adolescents to optimize efficacy, and effectively change the culture for sleep promotion (Kudchadkar 2014b).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite evidence that sleep disruption in hospitalized adults has a negative impact on outcomes, and inexpensive sleep promotion interventions can decrease morbidity for both adults and neonates, there is a lack of awareness in the pediatric community about modifiable risk factors for sleep disruption in hospitalized children and adolescents outside of the NICU environment. There is a critical need for a synthesis of the current evidence in children older than one month, to understand the potential benefits of specific sleep promotion interventions in a population undergoing active neurocognitive development. There are several risk factors for sleep fragmentation in acutely ill children, and several medications used to improve sleep (i.e. benzodiazepines, diphenhydramine) that may, in fact, have a negative effect on sleep quality. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the effect of non‐pharmacologic interventions to promote sleep in this vulnerable population.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of non‐pharmacological sleep promotion interventions in hospitalized children and adolescents on:

sleep quality and sleep duration; and

child or parent satisfaction, cost‐effectiveness, delirium incidence, length of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, and mortality

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

In order to ensure recommendations based on highest level evidence, we only included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), randomized cross‐over trials, and quasi‐RCTs (participant allocation not strictly random, i.e. date of birth or alternation).

Types of participants

Infants, children, and adolescents aged between 1 month and 18 years, admitted to the hospital for more than 48 hours. Infants and children could have been in for surgical or medical reasons, or needed mechanical ventilation. We also considered studies with participants both above and below the age of 18 years, if they were in an inpatient pediatric hospital setting, and the study also included children and adolescents between 1 month and 18 years.

We excluded studies that focused on infants < 1 month of age (44 weeks' postmenstrual age), or studies with infants > 1 month who had never left the hospital after birth, due to differences in sleep architecture in newborns, and in particular preterm infants. We also excluded studies focused solely on children with central or obstructive sleep apnea, because non‐pharmacologic interventions are unlikely to impact the physiologic and anatomic aspects of these conditions.

Types of interventions

We included studies investigating the effects of any of the following non‐pharmacological sleep promotion interventions on the sleep quality or sleep duration (or both) of children and adolescents aged 1 month to 18 years, in the pediatric inpatient setting.

Environmental interventions, including, but not limited to: earplugs, headphones, alarm modifications, white noise, or unit‐based 'quiet hours', lighting control or cycling, eye masks, and bright light therapy, or a combination

Behavioral Interventions, including, but not limited to: massage, music therapy, guided imagery, and kangaroo care (skin‐to‐skin contact)

Physical activity interventions, such as mobility or exercise during the day

Complementary and alternative therapies, such as aromatherapy and acupressure or acupuncture

Any other non‐pharmacological intervention intended to promote the sleep of children in the hospital

Studies could include one intervention, or a combination of interventions in a treatment arm, and compare them to usual care or an alternative intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Changes in objective and validated measures of sleep, assessed using a polysomnography or actigraphy (or both); specifically, total sleep time (TST, based on age‐based normative data), percentage rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, minutes of wake, percentage of slow‐wave sleep, sleep efficiency (Laffan 2010), and Sleep Fragmentation Index (SFI), during the period of the intervention (Haba‐Rubio 2004)

-

Subjective measures of sleep, as measured by:

parent and nurse surveys; and

subjective, validated sleep assessment tools, such as the Patient Sleep Behavior Observation Tool (Corser 1996; Cureton‐Lane 1997a), or the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Owens 2000).

We excluded studies if they did not report any outcomes relevant to sleep (objective or subjective measures, outlined above), given the focus of the review and the fact that interventions, like physical activity, massage, etc. are used for a multitude of purposes.

Secondary outcomes

Participant or parent satisfaction, as described by the study authors

Cost‐effectiveness ratios

Delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at time of hospital discharge

Length of mechanical ventilation (days)

Length of hospital stay (days)

Mortality

Search methods for identification of studies

We ran the first searches for this review in April 2018 and updated them in March 2019. We ran further updates between October 2020 and December 2021, except for Grey Literature Reports, which was not maintained after 2017.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases and trials registers.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 12) in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 12 December 2021)

PubMed US National Library of Medicine (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed; searched 12 December 2021)

Embase Elsevier (1980 to 12 December 2021)

CINAHLPlus EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1950 to 12 December 2021)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2021, Issue 12) in the Cochrane Library (searched 12 December 2021)

Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org/en; searched March 2019 and 10 December 2021)

ProQuest Digital Dissertations and Theses (searched March 2019 and 10 December 2021)

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 12 December 2021)

ISRCTN Registry (www.isrctn.com; searched 9 December 2021)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; trialsearch.who.int/AdvSearch.aspx; searched 12 December 2021)

We also searched the grey literature, using the following websites.

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu; searched 17 April 2018, archived Summer 2021, and updated 10 December 2021)

Grey Literature Reports at the New York Academy of Medicine Library (greylit.org; searched 17 April 2018, not updated after 2017, thus, search not updated).

We did not limit our search publication date or language, or exclude studies based on the year the study was performed, if all other inclusion criteria were met (Criteria for considering studies for this review). The exact search strategies for each source are reported in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles, as well as Google Scholar (scholar.google.com; 1980 to present, searched 10 December 2021), using the terms 'sleep' AND 'hospital' AND 'child'. We also handsearched relevant conference proceedings on 31 March 2020, including the Associated Professional Sleep Societies and the American Thoracic Society Conferences, and key sleep and pediatric journals, including the following:

Sleep (1990 to 1 December 2021);

Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine (2005 to 1 December 2021);

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine (1995 to 1 December 2021);

Sleep Medicine Reviews (1998 to 1 December 2021);

Pediatrics (1990 to 1 December 2021);

Pediatric Critical Care Medicine (2000 to 1 December 2021);

Hospital Pediatrics (2011 to 1 December 2021); and

JAMA Pediatrics (1990 to 1 December 2021).

Data collection and analysis

We only reported the methods used for this review. For methods that will be used in future updates of this review, please see Kudchadkar 2017 and Appendix 2.

Selection of studies

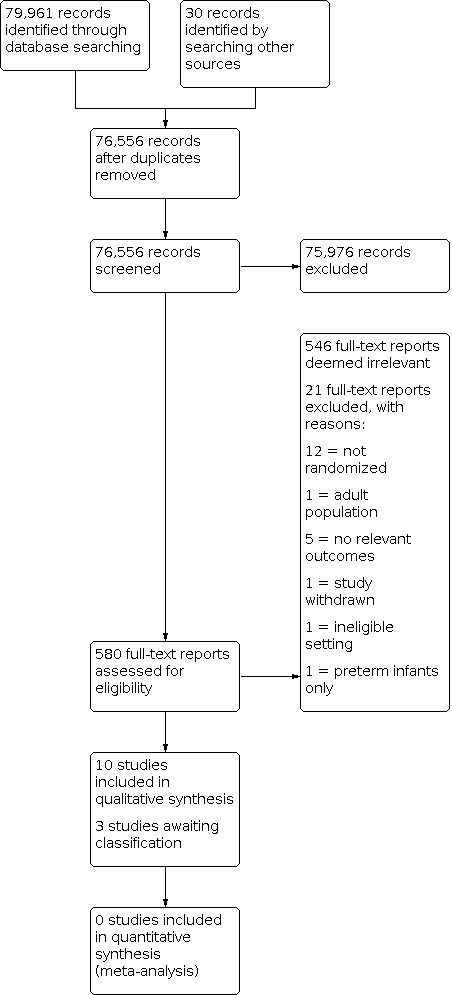

After merging the results of the above literature search strategy in Endnote (Endnote 2016), we removed duplicates and exported titles and abstracts into Excel (Microsoft 2016). We randomly assigned each study a number, and rearranged them into numeric order. Two pairs of review authors (JB, SB, RP, TW) screened an equal number of reports. The two review authors in each pair independently reviewed the titles and abstracts based on the inclusion criteria, defined under Criteria for considering studies for this review. Each review author classified abstracts as yes – include, or no – exclude. Each pair of review authors reviewed and discussed disagreements to reach consensus. If there was disagreement after discussion, they included the study for full‐text review. If there was any doubt of eligibility, we obtained the full text of the paper for review. The same pair of authors reviewed the full texts of the 'include' group of titles and abstracts. They discussed disagreements until a consensus was reached. A study was excluded from data extraction if both review authors agreed it should be excluded after they reviewed the full text. The final list of studies chosen by both pairs of review authors for data extraction were merged again and renumbered for random assignment to two independent review authors, as detailed in Data extraction and management. Results of the selection process are presented in Figure 1 (Moher 2009).

1.

PRISMA flow diagram for included studies

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data using a standardized form in Covidence, developed collectively by the review authors (Covidence). One review author entered data onto the form and the other member of the pair re‐entered the data using a double‐data strategy. All disagreements were resolved by group consensus and third party consultation, as needed. We extracted the following data.

-

Study characteristics

country of study

year of study

study design

method of randomization (if applicable)

unit of analysis

setting (inpatient general floor, subspecialty floor [i.e. oncology, surgery, etc.], PICU, or NICU)

outcome measures

conflict of interest and declaration of conflict of interest

-

Participant characteristics

age

sex

race

inclusion/exclusion criteria

comorbidity (prematurity, developmental delay, traumatic brain injury, surgery)

admission diagnosis

hospital length of stay

-

Intervention

type of intervention (earplugs, earmuffs, headphones, music therapy, white noise, unit‐based 'quiet‐time' protocol, alarm modifications, etc.)

timing of intervention

duration of intervention

frequency of intervention

any other associated interventions (i.e. sleep promotion 'bundles' using multiple interventions to promote sleep)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JS, RM) independently assessed the included studies for sources of systematic bias. We assessed studies using the Cochrane RoB 1 tool, recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For each included study, we classified risk of bias as low, high, or unclear for each of the following domains: random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other potential sources of bias (other bias); see Appendix 3). The two review authors discussed and resolved disagreements, or collaborated with a third or fourth review author, if needed.

Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

For individual studies, after verifying a normal distribution of continuous outcomes, we calculated mean values for the primary outcomes of interest (TST, SFI, sleep efficiency), and presented these with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Specifically, we calculated the mean difference (MD) when studies assessed the same outcome using the same assessment measure, and planned to present the standardized mean difference (SMD) when studies used different assessment measures for the same outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

Due to the nature of the intervention, we thought it was possible that we would encounter studies using cluster‐randomization, and cross‐over trial designs, and studies with more than two intervention groups. For these studies, we conducted the analysis as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook, and outlined below (Higgins 2021).

Cross‐over trials

We analyzed continuous data from a two‐period, two‐intervention, cross‐over trial using a paired t‐test. A paired analysis was possible if any of the following were available:

individual participant data;

means and standard deviations or errors of participant‐specific differences between measurements from the experimental and control groups;

MD and either a t statistic from paired t‐test or CI from a paired analysis; or

a graph of measurements on interventions and controls where individual matched data values could be identified and extracted.

Dealing with missing data

When possible, we contacted the original investigators of the included studies to provide missing participant data, including reasons for dropping out, and missing information regarding study design, to assist with risk of bias assessments.

Assessment of heterogeneity

By assessing variations in participant, intervention, and outcome characteristics, we examined clinical as well as methodological heterogeneity. These included the following.

Participant characteristics: age, sex, comorbidities, inclusion/exclusion criteria

Intervention characteristics: type of intervention, timing, duration

Outcome characteristics: method of measurement, timing

When clinical heterogeneity was too great, we planned to provide a narrative summary.

Assessment of reporting biases

We sought both published and unpublished literature to address publication bias. However, there were not enough studies to create a funnel plot to investigate reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We did not perform a meta‐analysis due to substantial clinical and methodological heterogeneity (see Assessment of heterogeneity). Instead, we undertook a narrative synthesis of included studies, presenting information in relevant tables (study characteristics and results, including comparisons between interventions, i.e. behavioral interventions versus usual care, physical activity interventions versus usual care). We also presented a comprehensive discussion of each study’s methodology or risk of bias (or both) that may have affected the quantitative result obtained. We reported the results without meta‐analysis, using the 2020 Synthesis without meta‐analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews reporting guideline (Campbell 2020). We used the SWiM reporting guideline to ensure transparent reporting of our narrative synthesis, including how we grouped studies, metrics, and methods used for synthesis, data presentation, and presentation of limitations.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses, using the statistical test for planned subgroup differences, however, we had too few trials, small sample sizes, and insufficient data available to do so. See Appendix 2 for subgroup details.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses. However, the number of trials, sample sizes, and data available were insufficient to do so. See Appendix 2 for details.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We summarized the results of each comparison (behavioral interventions versus usual care; physical activity interventions versus usual care), for the primary outcomes (objective and subjective measures of sleep), and the secondary outcomes (participant or parent satisfaction) in Table 1 and Table 2. We created the tables using GRADEpro GDT and Review Manager 5 software (GRADEpro GDT; Review Manager 2020). Using the GRADE approach, two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome as high, moderate, low, or very low, according to the presence of the following criteria:

limitations in design and implementation;

indirectness of evidence;

unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistent results;

imprecision of results; and

high risk of publication bias.

We provided a narrative description of important, clinically‐relevant findings.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We ran the searches in May 2018, August 2019, October 2020, and December 2021. We retrieved a total of 79,991 records and imported them into Covidence for screening; we identified and discarded 3435 duplicates (Covidence). We screened the titles and abstracts of 76,556 records, and excluded 75,976 irrelevant records. We assessed 580 full‐text reports and excluded 567 that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We identified 10 included studies, and three studies that are awaiting classification (Beardslee 1974; Ctri 2020; NCT03453814). The flow of studies for this review is shown in Figure 1.

Included studies

We included 10 studies in this review (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018; Potasz 2010; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983; White 1990). One study was only available as a conference abstract (Potasz 2010). The included studies were published between 1983 and 2019.

Study types

Eight of the included studies were parallel trials, randomized (RCT) at the individual level (Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018; Potasz 2010; Rennick 2018; White 1983; White 1990). One study was a cross‐over trial (Cone 2014), and one was a cluster‐randomized trial (Rogers 2019).

Participants and settings

In total, there were 528 participants in the included studies. Sample sizes ranged from 6 (Cone 2014), to 139 (Potasz 2010).

Seven studies were conducted in the United States (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Jacobs 2016; Rogers 2019; White 1983; White 1990), two in Canada (Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018), and one in Brazil (Potasz 2010).

The hospital setting varied between studies, and included an inpatient burn unit (Cone 2014), inpatient psychiatric unit (Field 1992), inpatient oncology unit (Hinds 2007a; Jacobs 2016; Rogers 2019), inpatient general pediatric unit (Papaconstantinou 2018; Potasz 2010; White 1983; White 1990), and a pediatric ICU (Rennick 2018). These settings reflected the populations of focus: children and adolescents with burns; with psychiatric disorders; those who were critically ill; those who were on oncology units, including those with central nervous system tumors; on general pediatric units; and those admitted for surgery.

Given the mix of included inpatient settings, the age of participants across studies ranged from 4 years to 22 years. Studies including participants 18 years and over, and children under 18; all were conducted in a pediatric inpatient setting.

Interventions

The most commonly studied category of non‐pharmacologic intervention (8 studies) was behavioral interventions (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983; White 1990). Two studies investigated physical activity interventions (Hinds 2007a; Potasz 2010).

No studies reported a focused environmental intervention, however, the multicomponent relaxation interventions did incorporate elements that included quiet time at night (Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019). There were no studies of complementary therapies, including acupuncture or acupressure.

The non‐pharmacologic sleep promotion interventions investigated in the included studies were heterogenous in the methods, timing, frequency, duration, and components; and ranged from short, one‐time interventions (touch therapy [Cone 2014]) to the entire hospital admission (Rennick 2018). The cross‐over trial had no specified washout period between intervention periods (Cone 2014).

1. Behavioral interventions

Multicomponent relaxation intervention

Three studies used a combination of behavioral approaches to develop a multicomponent relaxation intervention (Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019).

Papaconstantinou 2018 examined the effect of a Relax to Sleep intervention on sleep in general pediatric, surgery, or cardiology units. The Relax to Sleep intervention is comprised of one‐on‐one education for parents, with information about sleep, age, and developmentally appropriate instructions to train children in the use of diaphragmatic breathing exercises. Younger children were given a storybook to facilitate breathing exercises, and older children, a music file with a relaxation script; the exercises were practiced with the researcher. Guidance for parents included the importance of exposing their child to bright light each day.

Rennick 2018 investigated the effect of a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) soothing intervention, consisting of parental comforting (touch and reading), followed by a quiet period of music. A fleece headband was also offered to deliver soft music, or just reduce external noise after the reading session, for up to one hour. The intervention continued throughout the PICU and hospital ward stay.

In Rogers 2019, the multicomponent intervention aimed at relaxation included age‐appropriate sleep education and relaxation training on Day 0, followed by a parental‐implemented relaxation technique (book, massage). Stimulus control measures included measures to decrease nighttime disrupters, including 90‐minute protected periods for sleep with bundled care.

Massage

Two studies investigated the effect of massage on sleep outcomes.

In Field 1992, massage was administered for 30 minutes a day, for a duration of 5 days.

Jacobs 2016 administered massage 20 to 30 minutes a day, for two to three nights, after a baseline phase of two nights.

Parent‐recorded bedtime stories

Two studies investigated the effect of parent‐recorded bedtime stories on sleep (White 1983; White 1990).

In White 1983, parents recorded a 10‐minute bedtime story, which was played for the children in the intervention group on nights two and three, after one night of baseline.

The interventions in White 1990 consisted of (1) parent‐recorded story with parent absent; (2) stranger‐recorded story with parent absent; (3) no story and parent absent; (4) no story and parent present (convenience sample). Stories were only played on night two. For both studies, parents had the option to add individualized comments, or modify the story as they deemed fit.

Touch therapies

One cross‐over study examined the use of healing touch, which consisted of non‐invasive and gentle use of the practitioner’s hands, either directly on the clothed body or slightly above the child's body (Cone 2014). The touch therapy procedure was comprised of three techniques: (1) magnetic clearing (15 to 30 full length, smooth, continuous passes with both hands, one to six inches from the body); (2) mind clearing, with hands placed lightly on, or above, several sites around face, neck, and forehead; (3) chakra connection involved the practitioner placing their hands on the major and minor chakras of the body. Participants received both the touch therapy and usual care on successive nights; the order of intervention was randomized.

2. Physical activity interventions

Two studies investigated the effect of physical activity on sleep (Hinds 2007a; Potasz 2010)

Enhanced Physical Activity

Hinds 2007a explored an enhanced physical activity intervention with a stationary bicycle‐style exerciser, which was used for 30 minutes twice daily, for two to four days of hospitalization.

Play

In a conference abstract, Potasz 2010 reported the effect of play versus no play, where play included a visit to a toy library twice a day for one hour at a time, and taking toys back to the room, where trained professional facilitated activities.

Comparators

All studies compared the intervention to usual care (standard clinical care), with the exception of White 1990, in which the control group was parent present, and no story.

Outcomes

Included studies investigated the effect of non‐pharmacologic sleep promotion interventions on objective or subjective sleep outcomes, or both. None of the trials measured all outcomes relevant to this review.

Objective sleep assessment

One study used polysomnography to measure total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep latency, wake after sleep onset, % time in non‐rapid eye movement sleep stage 1 (N1), N2, N3, rapid eye movement (REM), and total minutes of N1, N2, N3, and REM (Cone 2014).

Five studies used actigraphy (Hinds 2007a; Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019). The actigraphic variables reported by these studies varied. Hinds 2007a reported 24‐hour sleep efficiency and total sleep time; while Jacobs 2016 explored those metrics in addition to nighttime‐specific total sleep time, sleep efficiency, wake after sleep onset, and long sleep episode. In Papaconstantinou 2018, sleep metrics were measured by daytime and nighttime periods (total sleep time, longest sleep period), in addition to nighttime awakenings, and wake after sleep onset. Parameters measured in Rennick 2018 included both daytime and nighttime sleep minutes, and nighttime arousals on the ward and at home; actigraphy was not used in the PICU due to concerns that sedatives and immobility might affect measures. Rogers 2019 reported daytime and nighttime percent sleep, mean duration of sleep episodes, longest sleep episode, mean duration of wake episodes, wake episodes, and longest wake episode.

Subjective sleep assessment

Five studies reported use of subjective sleep assessment (Field 1992; Papaconstantinou 2018; Potasz 2010; White 1983; White 1990). Field 1992 observed videos recorded during nighttime sleep, and coded them for active sleep versus awake, and lighting quietly, awake, and active. Papaconstantinou 2018 reported the effect of their intervention on the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Owens 2000), which was completed at baseline and five to seven days after hospital discharge. The conference abstract by Potasz 2010 reported use of sleep logs, without additional information about validation or reliability. Finally, two studies used the Sleep Onset Latency Behavior Catalog and Falling Asleep Behavioral Inventory, both of which comprised 54 different falling asleep behaviors to characterize participants' sleep behavior, for 45 minutes on each night of observation (White 1983; White 1990).

Participant/parent satisfaction

Two studies reported participant, or parental satisfaction, or both, with the non‐pharmacologic intervention used. Jacobs 2016 used an end‐of‐study questionnaire, using Likert‐scale responses on the perception of massage, and how the participant slept and felt after massage, along with open‐ended questions. In Rennick 2018, parental perception about the intervention was measured by research assistant observation, and recoding of child and parent responses.

Funding of studies

Eight studies were funded by grants (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983; White 1990); two provided no information on funding (Jacobs 2016; Potasz 2010). No sources of corporate funding were reported.

Excluded studies

We excluded 518 reports following full‐text review of 529 reports; we removed 17 because they were duplicates. We describe the reasons for excluding 21 studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. The most common reasons for excluding studies were observational study design (N = 8), and no relevant outcomes for this review (N = 5).

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane RoB 1 tool. Please see the Characteristics of included studies tables for further details. Figure 2 and Figure 3 display the risk of bias summary figures.

2.

Risk of bias graph summarizing the risk of bias across included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study

Green circle: low risk of bias Yellow: unclear risk of bias Red circle: high risk of bias

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Out of 10 studies, we assessed seven at low risk of bias for random sequence generation (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983). These studies all had clear descriptions of the randomization procedures. Two studies did not provide specifics on their randomization strategy and we classed them at unclear risk of bias (Jacobs 2016; Potasz 2010). We assessed one study at high risk of bias, because only children whose parents agreed not to stay at the bedside were randomized; if parents wanted to be present, they were allocated to the 'parent present' group (White 1990).

Allocation concealment

We rated studies at low risk of bias for allocation concealment if there were sufficient details for randomization of the sequence. We assessed six studies at low risk of bias (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983). Allocation concealment was unclear in two studies, due to insufficient information (Jacobs 2016; Potasz 2010). We assessed one study at high risk of bias as allocation could be dependent on parental presence at the bedside (White 1990).

Blinding

Performance bias

We assessed all 10 included studies at high risk of performance bias because of the inability and challenge of blinding participants and personnel to the intervention in all cases (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018; Potasz 2010; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983; White 1990).

Detection bias

We assessed only two studies at low risk of bias for detection because the outcomes assessors were adequately blinded (Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018). These studies relied on objective methods of assessment that would not be affected by knowledge of the intervention assignment. We assessed three studies at unclear risk of bias, due to inadequate information (Cone 2014; Field 1992; Potasz 2010). We assessed four studies at high risk of detection bias, because all of them used subjective assessment of sleep outcomes, and there was potential knowledge of the intervention assignment (Hinds 2007a; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983; White 1990).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed five studies at low risk of attrition bias, because they reported no or minimal loss to follow‐up after enrollment (Cone 2014; Hinds 2007a; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019). There was insufficient information to make a determination of bias for three studies (Jacobs 2016; Potasz 2010; White 1990). We assessed two studies at high risk of bias (Field 1992; White 1983). White 1983 reported 13 dropouts due to early discharge or parental decision to room‐in; Field 1992 reported that 32% of sleep videos were unavailable, due to compliance or technical difficulties.

Selective reporting

We did not assesses any studies at high risk of selective reporting bias. We assesses five studies at unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information in the text (Field 1992; Hinds 2007a; Potasz 2010; Rennick 2018; White 1990); and five studies at low risk of bias, because they fully and completely reported all prespecified outcomes (Cone 2014; Jacobs 2016; Papaconstantinou 2018; Rogers 2019; White 1983).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed four studies at unclear risk of bias from other potential sources; three due to insufficient information (Potasz 2010; White 1983; White 1990), and one because the order of touch therapy in the cross‐over study may have affected overall sleep time, due to insufficient washout time (Cone 2014).

Effects of interventions

The summary of findings for both behavioral interventions and physical activity interventions are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. We identified considerable between‐study clinical heterogeneity of participant populations, measurement tools and metrics used, study duration, and timing of outcome assessment. Thus, we were unable to pool the results in a meta‐analysis for any of the outcomes. When possible, we calculated between‐group differences and 95% CIs for individual studies. When data were insufficient to provide this information, we presented the data as described in Data synthesis, using Synthesis without meta‐analysis (SWiM) reporting guidelines (Campbell 2020), and the Cochrane Handbook (McKenzie 2021). We found inconsistent effects for all non‐pharmacologic sleep promotion interventions on objective and subjective measures of sleep.

Behavioral interventions versus usual care

Primary outcomes

1. Changes in objective and validated measures of sleep (polysomnography (PSG) or actigraphy)

We rated the certainty of evidence for all of the outcome changes in objective and validated measures of sleep as low.

Multicomponent relaxation intervention

Table 3 presents results for the three included studies with sufficient data that examined multicomponent relaxation interventions on an objective measure of sleep, using actigraphy (Papaconstantinou 2018; Rennick 2018; Rogers 2019). We did not synthesize these results because there were inconsistencies in the reporting of actigraphy metrics across studies, and small sample sizes, which did not allow us to translate medians (interquartile range [IQR]) to means (standard deviation [SD]) with confidence.

1. Multicomponent relaxation interventions versus usual care: objective sleep outcomes assessed using actigraphy.

| Study | Sleep outcomes | Mean (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Relax to sleep (N = 20) | Usual care (N = 23) | Group difference | |||

| Papaconstantinou 2018 | Total daytime sleep (in minutes) | 76.9 (50 to 106.9) | 113.6 (78.1 to 149.2) | −36.7 (−83.5 to 10.10) | 0.121 |

| Total nighttime sleep (in minutes) | 419.3 (385.7 to 453) | 369.7 (323.7 to 415.7) | 49.64 (‐7.19 to 106.5) | 0.085 | |

| Nocturnal awakenings (number) | 14.67 (11.94 to 17.40) | 14.69 (12.64 to 16.73) | ‐0.02 (‐3.27 to 3.23) | 0.989 | |

| Longest nocturnal sleep period (in minutes) | 116.6 (85.28 to 147.9) | 100.9 (81.02 to 120.8) | 15.65 (‐19.33 to 50.62) | 0.372 | |

| ‐ | Mean (SD) | Mean (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Wake after sleep onset (in minutes) | 163.9 (93.63) | 209.2 (121.2) | ‐45.34 (‐112.8 to 22.15) | 0.182 | |

| Rennick 2018 | Median (IQR) | ||||

| PICU soothing (N = 9) | Usual care (N = 6) | ||||

| Total daytime sleep (in minutes) | 300.6 (163.9 to 365.7) | 239.1 (169.63 to 374.6) | |||

| Total nighttime sleep (in minutes) | 510 (434 to 550.8) | 526 (413.4 to 596.1) | |||

| Arousals (number) | 41.33 (30.3 to 51.2) | 31 (22.1 to 34.4) | |||

| Rogers 2019 | Mean (± SD) | Cohen d | |||

| Intervention (N = 17) | Usual care (N = 16) | ||||

| Daytime percentage of sleep (%) | 17.3 (± 10.3) | 56.6 (± 10.5) | 0.114 | ||

| Daytime mean duration of sleep episodes (in minutes) | 16.1 (± 5.9) | 16.9 (± 6.2) | 0.132 | ||

| Daytime sleep episodes (number) | 4.6 (± 2.7) | 5.5 (± 3.8) | 0.273 | ||

| Daytime longest sleep episode (in minutes) | 41.8 (± 14.8) | 45.5 (± 16.3) | 0.238 | ||

| Daytime mean duration wake episodes (in minutes) | 167.2 (± 115.1) | 159.2 (± 126.8) | 0.066 | ||

| Daytime wake episodes (number) | 5.8 (± 2.4) | 7.2 (± 3.9) | 0.432 | ||

| Daytime longest wake episode (in minutes) | 361.1 (± 124.6) | 342.1 (± 139.6) | 0.144 | ||

| Nighttime percentage of sleep (%) | 56.6 (± 10.5) | 58.3 (± 12.4) | 0.157 | ||

| Nighttime mean duration sleep episodes (in minutes) | 23.1 (± 8.5) | 26.3 (± 14.5) | 0.269 | ||

| Nighttime sleep episodes (number) | 12.3 (± 2.2) | 12.5 (± 3.0) | 0.076 | ||

| Nighttime longest sleep episode (in minutes) | 87.6 (± 32.0) | 92.9 (± 26.0) | 0.182 | ||

| Nighttime mean duration wake episodes (in minutes) | 17.1 (± 5.4) | 17.9 (± 9.4) | 0.104 | ||

| Nighttime wake episodes (number) | 10.7 (± 2.4) | 10.9 (± 2.6) | 0.080 | ||

| Nighttime longest wake episode (in minutes) | 104.8 (± 26.8) | 112.0 (± 60.0) | 0.155 | ||

CI: confidence intervals; N: number; SD: standard deviation.

Papaconstantinou 2018 found no clear difference in total nighttime sleep between the Relax to Sleep Intervention (mean difference [MD] 50 minutes, 95% confidence interval [CI] ‐7.19 to 106.5; 1 study; 48 participants) and usual care (mean total sleep duration 370 minutes); and no clear difference in the longest continuous nighttime sleep period (MD 16 minutes, 95% CI ‐19.33 to 50.62). They also suggested there may be a decrease in wake after sleep onset (WASO) with the intervention (MD ‐45 minutes, 95% CI ‐112.8 to 22.15).

A second study, Rennick 2018, with 20 participants, suggested PICU soothing may slightly increase median sleep duration during daytime hours over usual care (300.62 minutes, IQR 163.9 to 365.7 versus 240 minutes, IQR 170 to 375). There may be no clear difference between PICU soothing and usual care on median sleep duration at night (510 minutes, IQR 434 to 550.8 versus 526 minutes, IQR 413.44 to 596.06).

Rogers 2019 (33 participants) suggested that there may be no clear difference across the study period for any daytime or nighttime sleep variables in children receiving the multicomponent intervention compared to controls, including percentage of sleep, number of sleep episodes, mean duration of sleep episodes, longest sleep episode, mean duration of wake episodes, number of wake episodes, or longest wake episodes. See Table 3 for breakdown of results.

Touch Therapy

One cross‐over RCT with 10 participants investigated the effect of healing touch compared to usual care on sleep, using polysomnography (Table 4). The study authors reported that healing touch may be more effective than usual care for total sleep time (391 minutes, IQR 251 to 467 versus 331 minutes, IQR 268 to 373; P = 0.02). There could also be an increase in sleep efficiency with healing touch (76%, IQR 53 to 90 versus 66%, IQR 55 to 78; P = 0.04); more REM periods (4.5, IQR 2 to 5 versus 3.5, IQR 2 to 4; P = 0.03), and more N2 minutes (213 minutes, IQR 136 to 236 versus 160, IQR 107 to 204; P = 0.03). However, there may be no difference in sleep latency, number of awakenings, WASO, N3 minutes, or the proportion of time spent in each sleep stage (Cone 2014).

2. Healing touch versus usual care: objective sleep outcomes assessed using polysomnography.

| Study | Objective sleep outcome | Sleep outcome: median (interquartile range) | P value | |

| Healing touch (N = 10) | Usual care (N = 10) | |||

| Cone 2014 | Total sleep time (in minutes) | 391 (251 to 467) | 331 (268 to 373) | 0.02 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 76 (53 to 90) | 66 (55 to 78) | 0.04 | |

| Sleep latency (in minutes) | 8.4 (2.8 to 34.9) | 17.2 (13.5 to 48) | 0.20 | |

| Awakenings (number) | 32 (25 to 38) | 30 (23 to 32) | 0.42 | |

| Wake after sleep onset | 99 (46 to 210) | 107 (53 to 194) | 0.77 | |

| REM periods (number) | 4.5 (2.0 to 5.0) | 3.5 (2.0 to 4.0) | 0.03 | |

| N1 stage (in minutes) | 26 (21 to 32) | 28 (18 to 30) | 1.0 | |

| N2 stage (in minutes) | 213 (136 to 236) | 160 (107 to 204) | 0.03 | |

| N3 stage (in minutes) | 63 (29 to 93) | 34 (8 to 120) | 1.0 | |

| REM stage (in minutes) | 83 (62 to 91) | 60 (40 to 86) | 0.20 | |

| N1 (% of normal) | 212 (174 to 241) | 304 (197 to 531) | 0.11 | |

| N2 (% of normal) | 110 (103 to 136) | 123 (85 to 132) | 0.23 | |

| N3 (% of normal) | 67 (44 to 110) | 49 (31 to 125) | 0.43 | |

| REM (% of normal) | 95 (82 to 101) | 86 (47 to 116) | 0.04 | |

N1, N2, N3: non‐rapid eye movement sleep stage 1, 2, 3; REM: rapid eye movement

Massage

Table 5 presents the results of Jacobs 2016 (34 participants), which investigated the effect of massage compared to standard care on actigraph sleep parameters. There was insufficient information to report univariate statistics, and SDs or CIs, thus we presented the results of the mixed‐effect model. The mixed‐effect model showed that total sleep time (TST) may be similar for the massage group (391 minutes at baseline plus 53 minutes at end) compared to standard care (431 minutes at baseline minus 30 minutes at end), as was sleep efficiency.

3. Massage versus usual care: objective sleep outcomes assessed using actigraphy.

| Study | Objective sleep outcome | Main effect of intervention (beta) | P value |

| Jacobs 2016 | Total sleep time (in minutes) | ‐60.6 | 0.22 |

| Total nighttime sleep (in minutes) | ‐26.6 | 0.51 | |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | ‐8.0 | 0.12 | |

| Nighttime wake episodes (number) | ‐1.3 | 0.59 | |

| Wake after sleep onset nighttime (in minutes) | 39.6 | 0.35 | |

| Nighttime long sleep episode (in minutes) | ‐1.1 | 0.35 |

Mixed‐effects model controlling for age, gender, and reason of admission. Measures of variation and comparisons between interventions were not provided for the univariate analysis.

2. Changes in subjective measures of sleep (parent/participant surveys and validated sleep assessment tools)

We rated the certainty of the evidence contributing to this outcome as very low, meaning we are very uncertain about the findings.

Multicomponent relaxation intervention

One study reported the effect of a multicomponent relaxation intervention (Relax to Sleep) compared to usual care on Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) scores, five to seven days after discharge from the hospital (Papaconstantinou 2018). The Relax to Sleep program may reduce scores on the CSHQ more than usual care (MD ‐3.2, 95% CI ‐6.21 to ‐0.19; P = 0.037; 1 study, 48 participants), but the evidence is very uncertain.

Massage

One study, Field 1992, reported the effect of massage versus usual care on sleep, using video observation (72 participants). Videos were coded for (1) quiet sleep (no body movements), (2) active sleep (body movement), (3) awake and lying quietly, and (4) active and awake. Only 68% of tapes were available, due to noncompliance and technical issues. The findings suggested that massage may increase the per cent of time asleep over five days (MD 11.6 minutes; P = 0.01) more than the control group (MD 2.4; P = ns), and may decrease nighttime wakefulness (% time awake) over the same period (MD ‐11.2; P = 0.05) over usual care (MD 2.3). However we are very uncertain about the evidence.

Bedtime stories

Two studies (112 participants) from the same author group observed and reported the effect of bedtime stories on sleep behaviors, with the Sleep Onset Behavior Catalog (White 1983; White 1990).

In White 1983, the authors compared parent‐recorded bedtime story versus no bedtime story. They found that parent‐recorded bedtime stories may lead to longer mean duration of sleep (measured on the third night) compared to usual care (23 minutes versus 15 minutes; 18 participants). Time to fall asleep might also be shorter following parent‐recorded bedtime stories (22 minutes versus 27 minutes) versus no story. The authors neither reported the P values for these results nor stated if these differences between the groups were statistically significant.

White 1990 (94 participants) evaluated the effect of recorded bedtime stories on sleep latency in four groups, using the Sleep Onset Behavior Catalog: parent‐recorded/parents absent versus stranger‐recorded/parents absent; versus no story/parents absent; versus no story/parents present. Children listening to a parent‐recorded story may have longer sleep latencies (mean 57.5 minutes) compared to when a parent is present (43.5 minutes); both groups had longer sleep latency than those who had the stranger‐recorded story, and no story/parent absent (P < 0.001). However the evidence is very uncertain.

Secondary outcome

Participant or parent satisfaction, or both

The certainty of evidence for participant or parent satisfaction, or both, was rated as very low.

One study investigating the effects of massage versus usual care suggested that satisfaction may be increased in the massage group compared to usual care (Jacobs 2016; 34 participants). They reported that 87% (13/15) of participants felt they slept better, and most parents in the study (92%; 11/12) reported that they wanted their child to receive massage in the future.

Another study of multicomponent relaxation intervention versus usual care in children in pediatric ICU reported that parents thought the music, touch, and reading components of the intervention were acceptable and feasible, with positive effects on their children (Rennick 2018; 20 participants).

None of the studies of behavioral interventions evaluated cost‐effectiveness, delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at hospital discharge, length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, or mortality.

Physical activity interventions versus usual care

Primary outcome

Changes in objective and validated measures of sleep (PSG or actigraphy)

Enhanced physical activity

One study investigated enhanced physical activity compared to usual care (Hinds 2007a; 29 participants). The results suggested that there may be no clear difference between the groups in either total sleep time or sleep efficiency, shown in Table 6. We rated the certainty of this evidence as low.

4. Enhanced physical activity versus usual care: objective sleep outcomes measured using actigraphy.

| Study | Objective sleep outcome | Mean (SD) | P value | |

| Enhanced physical activity (N = 12) | Usual care (N = 15) | |||

| Hinds 2007a | Total sleep time (in minutes) | 606.3 (144.6) | 562.3 (122.4) | 0.47 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 73 (15.6) | 71 (16.7) | 0.85 | |

N: number; SD: standard deviation.

Changes in subjective measures of sleep (parent/participant surveys and validated sleep assessment tools)

Play activities

One study investigated play versus a no‐play group to promote sleep, using sleep logs (Potasz 2010; 139 participants). For this study, we only have a conference abstract and as such, there is insufficient information to determine effect estimates between groups. The findings provided in the abstract suggest that there may be inconsistent findings across age groups and gender. The authors reported that TST in the no‐play group was 49% higher in four‐ to seven‐year‐old boys, 9.5% higher in 7.1‐ to 11‐year‐old boys, and 22% higher in 11.1‐ to 14‐year‐old boys. However, girls from the two youngest age groups may have more sleep in the play group (4% higher for 4‐ to 7‐year‐old girls, and 14% higher for 7.1‐ to 11‐year‐old girls); girls in the oldest age group had 46.1% more sleep in the no‐play group group. Boys in the usual care group had more daytime sleep across all age groups (4 to 7 years: 26%; 7.1 to 11 years: 46%; 11.1 to 14 years: 36%), similar to girls in the oldest two age groups of the no‐play group (7.1 to 11 years: 23%; 11.1 to 14 years: 59%). In contrast, the youngest girls had more sleep during the day in the play group (13%). We rated the certainty of this evidence as very low.

Secondary outcomes

None of the studies of physical interventions evaluated participant or parent satisfaction, cost‐effectiveness, delirium incidence or delirium‐free days at hospital discharge, length of mechanical ventilation, length of hospital stay, or mortality.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our review sought to assess the effects of non‐pharmacologic sleep promotion interventions for hospitalized children and adolescents. All included studies took place in inpatient pediatric settings, including a pediatric intensive care unit (ICU), and burn, oncology, general pediatric, surgical, cardiology, and psychiatric units. The types of interventions varied widely, including behavioral interventions, such as multicomponent relaxation interventions, massage, and touch therapy; and physical activity interventions, such as exercise bicycle and age‐appropriate play. The timing, duration, and frequency varied across interventions, anywhere from one‐time interventions to the entire duration of hospital admission.

We included 10 studies, with a total of 528 participants, who ranged in age from 3 years to 22 years. Compared with usual care or controls, behavioral and physical activity interventions showed inconsistent effects across objective and subjective metrics of sleep quality and quantity. A study of touch therapy found it may improve total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and number of REM periods, with low‐certainty evidence. Other studies, including multicomponent relaxation interventions, bedtime stories, massage, physical activity, and play interventions demonstrated variable effects on sleep quality and duration, with low‐ or very low‐certainty evidence.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

It is remarkable that none of the included studies enrolled children under three years of age, who have a high burden of hospitalization and are undergoing neurodevelopment most rapidly. For example, recent point prevalence studies in the USA, Canada, and Europe found that two‐thirds of all children admitted to pediatric ICUs for more than 72 hours are under the age of three years (Choong 2021; Ista 2020; Kudchadkar 2020). The majority of studies in this review evaluated the effect of non‐pharmacologic sleep promotion interventions in school‐age children and adolescents, identifying major knowledge gaps for a vulnerable infant and toddler inpatient population. Thus, the omission of children in younger age groups limits generalizability of the findings. Also, none of the studies specifically addressed children with functional impairments, for whom specific interventions may not be applicable (i.e. lighting interventions in blind children, noise interventions for deaf children, physical activity interventions for children with limited mobility). However, the included studies did represent a wide spectrum of pediatric inpatient settings, which is a strength of the evidence.