Abstract

Purple membrane (PM) is composed of several native lipids and the transmembrane protein bacteriorhodopsin (bR) in trimeric configuration. The delipidated PM (dPM) samples can be prepared by treating PM with CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) to partially remove native lipids while maintaining bR in the trimeric configuration. By correlating the photocycle kinetics of bR and the exact lipid compositions of the various dPM samples, one can reveal the roles of native PM lipids. However, it is challenging to compare the lipid compositions of the various dPM samples quantitatively. Here, we utilize the absorbances of extracted retinal at 382 nm to normalize the concentrations of the remaining lipids in each dPM sample, which were then quantified by mass spectrometry, allowing us to compare the lipid compositions of different samples in a quantitative manner. The corresponding photocycle kinetics of bR were probed by transient difference absorption spectroscopy. We found that the removal rate of the polar lipids follows the order of BPG ≈ GlyC < S-TGD-1 ≈ PG < PGP-Me ≈ PGS. Since BPG and GlyC have more nonpolar phytanyl groups than other lipids at the hydrophobic tail, causing a higher affinity with the hydrophobic surface of bR, the corresponding removal rates are slowest. In addition, as the reaction period of PM and CHAPS increases, the residual amounts of PGS and PGP-Me significantly decrease, in concomitance with the decelerated rates of the recovery of ground state and the decay of intermediate M, and the reduced transient population of intermediate O. PGS and PGP-Me are the lipids with the highest correlation to the photocycle activity among the six polar lipids of PM. From a practical viewpoint, combining optical spectroscopy and mass spectrometry appears a promising approach to simultaneously track the functions and the concomitant active components in a given biological system.

keywords: membrane protein, lipid compositions, mass spectrometry, delipidation

Significance

We investigated the roles of the native purple membrane (PM) lipids via correlating the lipid compositions of delipidated PM (dPM) and the photocycle of the constituent bacteriorhodopsin (bR). The native lipids in PM were removed at different levels upon treatment with CHAPS for different reaction periods. The absorbances of the extracted retinal served as the interior reference for normalizing the concentrations of lipids in dPM, quantified by mass spectrometry. The photocycle kinetics of bR coincides with the lipid compositions probed with transient difference absorption spectroscopy. The “top-down” strategy upon gradual strip-off of the lipids from native conditions, coupled with mass spectrometry and spectroscopic methods simultaneously, offers a better way to understand the lipid-protein interactions and the concomitant biological activity.

Introduction

Bacteriorhodopsin (bR) is a light-driven proton pump protein from the halophile Halobacterium salinarum (1) and has a retinal covalently linking to Lys-216 to form a protonated retinal Schiff base (PRSB) (2,3). In general, three bRs and ca. 10 lipids per bR (4,5) are packed in a hexagonal structure (6), forming a primitive unit of purple membrane (PM). The primary lipids of PM include two nonpolar lipids, squalene and vitamin MK8, and six polar lipids, S-TGD-1, PGP-Me, PG, PGS, BPG, and GlyC (5,7,8,9,10), as shown in Fig. 1. These native lipids are known to play roles in maintaining the conformational flexibility of bR (11) and the integrity of PM (5,12,13,14,15,16). Neutron diffraction has revealed that at least two S-TGD-1 lipids appear in the inter- and intratrimer spaces (17). Studies of the lipid-protein interactions using x-ray crystallography have been carefully reviewed by Cartailler and Luecke (12). The minor phospholipid BPG (BPG/retinal < 0.37) is presumably located in the intertrimer space to mediate the interactions between trimers and to maintain the integrity of PM (5). Another minor phospholipid, PGS, allows the reconstitution of bR trimers into a hexagonal lattice and should be presented in the intertrimer space (12,13).

Figure 1.

The molecular structures of native polar lipids in PM. The numbers in parentheses denote their corresponding lipid/retinal molar ratios in the total lipid extract of the PM (5).

While the PM lipids play roles in the PM integrity, the types of the lipids surrounding bR strongly affect the photocycle kinetics (4,11,18,19). The light-adapted bR in PM manifests a strong absorption band at 568 nm, which is correlated to the S0→ 1Bu-like electronic transition of the PRSB (20). The absorption of a yellow photon triggers the photoisomerization of PRSB from all-trans to 13-cis (21), followed by a photocycle in the form of a series of spectrally distinguishable intermediates, which are associated with the status of the retinal Schiff base (1,22),

| (1) |

After the trans-to-cis retinal photoisomerization to generate intermediate K, the L-to-M transition involves a proton migration from PRSB to Asp-85 (23,24,25), in concomitance with the proton release at the extracellular side (26,27). Subsequently, the reprotonation of the deprotonated Schiff base via acquiring a proton from Asp96 occurs in the M-to-N transition (25,28). Afterward, the reisomerization of the retinal from 13-cis to all-trans (29) and reprotonation of Asp-96 (28,30) occurs in the generation of intermediate O, followed by the structural relaxation in the decay of intermediate O.

The studies of photocycle kinetics of bR have been carried out in various membrane environments and oligomeric conditions, such as bR in delipidated PM (dPM) (31,32,33,34), monomerized bR (mbR) in detergent micelles (34,35,36), bR reconstituted in native lipids (36) and artificial lipid membranes (37,38), and bR in nanodiscs (nbR) (39,40,41). The findings of these studies have indicated that the membrane environments and the oligomeric conditions greatly affect the photocycle kinetics of bR. To summarize, the negatively charged lipids, such as DMPG and DOPG, preserve the features of the photocycle of nbR, mainly in terms of the transient populations of intermediates M and O (39). The addition of the native lipids helps the formation of trimers and the recovery of the photocycle activity of the damaged bR conformation (42). Adding PGP-Me and PGS to the monomerized bR solubilized in Triton X-100 helps recover the photocycle activity (36). S-TDG-1 is essential for the photocycle activity and the integrity of the trimeric bR (14). In contrast, the presence of GlyC does not significantly alter the kinetics of intermediate M (43). Although many studies have been carried out to study the lipid-protein interaction in PM, no studies have simultaneously quantified the lipid compositions and the concomitant photocycle of bR during the delipidation of PM without sacrificing the trimeric configuration.

Numerous detergents have been utilized in perturbing the structures of PM and the photocycle activity. Triton X-100 was used to prepare the monomerized bR (34,35,36,44,45); CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) was used to mildly remove the lipids to prepare the dPM (34,46), which retained the trimeric form; anionic detergent SDS (47) and cationic detergent CTAB and its analogs (48) were used to denature the secondary structure of bR. Several neutral detergents, such as n-dodecyl-β-maltoside, octylethylene glycol dodecyl ether, and diethylene glycol mono-n-hexyl ether, were also used to influence the photocycle kinetics (49,50,51). In this work, we prepared various dPM samples (46) with different lipid removal levels by treating PM with the surfactant CHAPS for different reaction times. The monomerization of PM was not a concern since its distinguishing photocycle kinetics was not observed in our dPM samples (34,35). The bR oligomeric status of each dPM sample was examined using CD spectroscopy. The trimeric configuration of bR was found to be preserved in all dPM samples. The lipid compositions of the various dPMs were analyzed using mass spectroscopy, where the ratio of the concentration of each lipid after a certain period of CHAPS treatment with respect to its concentration in PM was quantified. For comparison of the lipid composition of the various dPMs in a quantitative manner, the concentration of constituent bR in each sample was measured by using the absorbance of extracted retinal at 382 nm as the internal reference to normalize the signal intensity of the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of each lipid. The ability to quantify the lipid compositions allows us not only to study the removal rate of different PM lipids by CHAPS but also to correlate the photocycle kinetics of bR in the various dPMs, measured using transient difference absorption spectroscopy, with their lipid compositions. The photocycle kinetics of the constituent bR were found to significantly coincide with the lipid compositions in the various dPMs.

Methods

Materials preparation

Preparation of PM and dPM

PM from H. salinarium S9 strain was prepared following the established procedure (52) and then further purified using sucrose gradient centrifugation. The PM-containing fraction was collected and then resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.3 and 0.4 mM sodium azide. To collect the pure PM pallet, the PM suspension was centrifuged at 87,000 × g for 1.5 h at 4°C using a swing bucket rotor (SW28, Beckman Coulter, IN, USA). The detergent CHAPS was used to partially remove the native lipids of PM to prepare dPMs (46). In detail, the purified PM pallet was first resuspended in a buffer containing 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 27 mM KCl, at pH 5.8, and the PM suspension was further diluted to a concentration containing 0.5 mg bR mL−1. To prepare each dPM sample, 24 mL of the PM suspension was centrifuged at a speed of 16,600 × g (UNIVERSAL 320 R, rotor mode 1615, Hettich, Tuttlingen, Germany) for 1 h at 25°C to obtain a PM pellet. The pure PM pellet was further dispersed in 2.4 mL of the buffer solution containing 5 mM of sodium acetate at pH 5.5 and 20 mM of CHAPS upon reaction for 5 min, 1 h, and 1 day at 23°C in dark under stirring. To stop the reaction, 0.8 mL of each CHAPS-treated suspension was diluted to 16.0 mL using phosphate buffer at pH 5.8, containing 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 27 mM KCl, followed by centrifugation at 16,600 × g (UNIVERSAL 320 R, rotor mode 1615, Hettich) at 25°C for 45 min. The dPM pellets were collected and redispersed in phosphate buffer at pH 5.8, containing 2 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 27 mM KCl, and 3 mM CHAPS. The sample names dPM-5 min, dPM-1 h, and dPM-1 day refer to the dPM samples with CHAPS treatment times of 5 min, 1 h, and 1 day, respectively. It is worth mentioning that bR in dPM retained the trimeric configuration and no dPM aggregation was observed in the presence of 3 mM CHAPS. Then the solutions were diluted to the concentrations of OD (optical density) at 0.3 at ca. 560 nm for CD and ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) steady-state measurements and OD at 0.7 for transient absorption measurement with the optical length of 1.0 cm, respectively.

Extraction of the lipids in dPM

The remaining lipids in the aforementioned dPM samples were extracted using the method described by Yeh et al. (53) for further lipid quantification using mass spectrometry. A dose of 200 μL of the PM or dPM samples of the concentration with OD at 7.4 at 1.0 cm optical length (equivalent to OD = 0.49 upon dilution ×15) was mixed with 250 μL of methanol and 500 μL of chloroform and vigorously shaken for 1 min, followed by centrifugation at 21,330 × g (Centrifuge 5424 R, rotor model FA-45-24-11, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min at 20°C. After the phases separated clearly, the aqueous phase at the upper layer was discarded, and then 250 μL DI water and 250 μL chloroform were added to the organic phase and mildly shaken. Subsequently, another centrifugation with the aforementioned condition was performed to achieve phase separation. The aqueous phase in the upper layer and the denatured protein moiety were discarded, and 600 μL of the organic phase in the lower layer was extracted and dried under N2 purge. The yellow residue was dissolved with 110 μL of tetrahydrofuran, followed by the addition of 900 μL of a solution containing 20% (v/v) 5 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate aqueous solution and 80% methanol. These solutions were mainly composed of the dissolved retinal and lipids. The absorbances at 382 nm attributed to retinal were used to measure the concentration of bR in each sample, which could be treated as the internal reference to normalize the signal intensity of the m/z of each lipid.

Steady-state absorption and CD spectra

Steady-state UV-vis absorption spectra were collected with a spectrometer from Ocean Optics (USB4000-UV-VIS, Ocean Optics, FL, USA). CD spectra were recorded with a spectrometer (J-815, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan), upon 5 averages at 0.2-nm intervals in 700−400 nm at 23°C. Quartz cuvettes of optical pathlengths of 0.2 and 1.0 cm were used for the steady-state absorption and CD measurements, respectively.

Quantification of lipid composition in dPM samples using mass spectrometry

The elution solution, containing 20% (v/v) of 5 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate aqueous solution and 80% of methanol, was used for loading a sample into a quadrupole-based electron-spray mass spectrometer (LCMS-2020, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The samples containing the extracted lipids and retinal were loaded with the elution solution at a speed of 0.1 mL min−1, and detected using an absorption system (SPD-40V, Shimadzu) and a quadrupole-based electron-spray mass spectrometer (LCMS-2020, Shimadzu) to determine the retinal concentration and m/z of the lipids, respectively. The electrospray voltage was controlled at 4.5 kV. The interface temperature and desolvation line temperature were set at 350 and 250°C, respectively. N2 was used as a nebulizing gas and drying gas at flow rates of 1.5 and 15 L min−1, respectively. The injection volumes and dilution factors were also examined.

Time-resolved difference absorption spectra

The experimental setup of the transient absorption is shown in Fig. S1. A frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser (LS-2137U, LOTIS TII, Minsk, Belarus) provided the 532-nm pulsed photons and was introduced through a mechanical shutter (VS25, UNIBLITZ, NY, USA) to decouple the 10-Hz laser irradiation rate to 5, 2, 1, and 0.5 Hz to prevent overshooting and an aqueous solution containing 300 mM CoCl2 to reduce the laser power. Then the attenuated laser beam was equally divided into two rays with a beamsplitter (BSW16, Thorlabs, NJ, USA); one ray was probed with a power meter (S470C, Thorlabs) and the other was used to excite the sample at a fluence of 0.38 mJ per pulse with a cross section of 0.79 cm2 (equivalent to 0.48 mJ cm−2 per pulse). Continuous-wave broadband light from a tungsten lamp (SLS201L, Thorlabs) was introduced to the sample holder via an optical fiber (FG-550-UER, Thorlabs). The excitation laser and the continuous-wave probe beam perpendicularly crossed in the center of the sample cell. After passing through the sample cuvette, the broadband light was collected with an optical fiber (model 77532, Oriel Instruments, CA, USA) and introduced to a monochromator (model 218, McPherson, MA, USA) to define the detection wavelengths in the range of 380–710 nm at a 15-nm interval. A photomultiplier (R928, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan) was used to probe the photon signals, and a 200-MHz digital oscilloscope (24MXs-B, LeCroy, NY, USA) was used to record and store the electronic signals. A photodiode (DET25K/M, Thorlabs) was used to collect the laser scattering and provided the triggers. The evolution of the absorbance difference at a given wavelength λ, ΔAt(λ), was derived using Eq. 2.

| (2) |

where St(λ) and S0(λ) denote the dc-coupled voltages from the photomultiplier at wavelength λ in the presence and absence of the excitation laser, respectively. Temporal profiles upon 200 laser excitations were averaged to increase the signal-to-noise ratio.

Results and discussions

Various dPM samples were prepared by dispersing PM in suspension in the presence of CHAPS for different reaction periods, e.g., 5 min, 1 h, and 1 day. The corresponding samples were named dPM-5 min, dPM-1 h, and dPM-1 day, respectively. The trimeric/oligomeric status of bR in each dPM sample was confirmed with steady-state absorption and CD spectra. The corresponding constituent lipids of dPMs were quantified by electron-spray ionization mass spectrometry, and the concomitant photocycle kinetics of bR in these dPMs were characterized with transient difference absorption spectroscopy.

Steady-state absorption and CD spectra

In comparison with that of the PM sample, the absorption maximum of the PRSB of bR in the dPM-5 min sample shifted from 568 to 564 nm, as shown in Fig. 2 A, whereas a minute further blueshift to 563 nm was observed for the dPM-1 day sample. The result is consistent with the previous report (34). The biphasic CD features (54,55,56) of all dPM samples (Fig. 2 B) implied the preservation of the bR trimeric configuration. Therefore, the concomitant photocycle kinetics can be solely influenced by the lipid composition of dPM rather than the oligomeric status.

Figure 2.

(A) Steady-state absorption spectra of PM and dPMs upon treatment of PM with CHAPS for different reaction periods. The spectra were normalized with respect to the absorbance of the retinal protonated Schiff base band at ca. 560 nm. (B) The corresponding circular dichroism spectra. The concentrations of constituent bR in each sample were roughly 5 μM. The samples were light adapted for 30 min before measurement. To see this figure in color, go online.

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of lipid compositions of dPM

The retinal absorbances in different PM and dPM samples were measured to calibrate the concentrations of bR in each sample. After the extracts from the PM and dPM samples were dissolved in solution containing 20% of 5 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate and 80% of methanol according to the procedures by Yeh et al. (53), the absorption features attributed to the retinal were all characterized at 382 nm (57), as shown in Fig. S2. The elution profiles of the retinal extracted from the PM and the dPM samples reaching the optical detector, probed at 386 nm using different dilution factors and injection volumes, are shown in Fig. S3. A 50% dilution of a sample with the same injection volume resulted in 50% of the integrated absorption intensity, while doubling the injection volume also doubled the integrated absorption intensity, as listed in Table S1. That is, the integrated absorption intensities of the samples in Fig. S3 were proportional to the concentrations and injection volumes of the PM and dPM extracts. Accordingly, the integrated absorption strengths were used to normalize the intensities of the ion signals in mass spectra for further quantification of the lipid compositions of the PM and the dPM extracts.

The mass spectra of PM at different concentrations and injection volumes after normalization with respect to the retinal concentrations, using the integrated absorption intensities in Table S1, are shown in Fig. S4. The mass spectra were assigned based on the previously reported m/z of each lipid, as listed in Table 1 (9). The samples injected into the mass spectrometer without dilution were shown not to be within the linear response region judged by the unproportional intensities of PGP-Me and PGS, as shown in Fig. S4 and listed in Table S2. To avoid incorrect quantification, the dPM samples were diluted for mass spectroscopic detection and the following discussions.

Table 1.

The m/z of native lipids in PM (9)

| Lipid | Most abundant mass | Ion | m/z |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPG | 1522.30 | [BPG – 2H]2– | 759.64 |

| PG | 806.67 | [PG – H]– | 805.67 |

| PGS | 886.63 | [PGS – H]– | 885.62 |

| PGP-Me | 900.66 | [PGP-Me – H]– | 899.65 |

| GlyC | 1934.42 | [GlyC – 2H]2– | 966.20 |

| S-TGD-1 | 1218.79 | [S-TGD-1 – H]– | 1217.78 |

The normalized mass spectra of the lipid extracts in the PM and the three dPM samples with respect to their corresponding retinal concentrations are shown in Fig. 3. The concentration dependence on the dilution factors and injection volumes rarely manifested. The relative signal intensity of each lipid in each dPM sample with respect to that in the PM sample upon averaging the four experimental conditions in Fig. 3 are summarized in Table S3 and Fig. 4. After a 5-min treatment with CHAPS, the intensities of the lipid ions of PGP-Me at m/z = 900 and PGS at m/z = 886 significantly decreased. As CHAPS treatment time was increased, these signals were found to decrease further. In contrast, BPG at m/z = 760 and GlyC at m/z = 966 were barely removed even after a 1-day treatment with CHAPS. This result was probably due to their greater hydrophobicity, which is attributed to their four nonpolar hydrocarbon tails, which possess higher affinity to the hydrophobic surface of bacteriorhodopsin peripheral (58), as shown in Fig. S5. Moreover, Catucci et al. have shown that the presence of GlyC is essential for the refolding and retinal binding of unfolded bR (59), implying the strong affinity of GlyC in functioning bR. Regarding PG and S-TGD-1, their removal rates are slower than those of PGS and PGP-Me. Essen et al. have demonstrated that S-TGA-1 binds into the central compartment of bR trimers (15). According to the CD spectrum in Fig. 2 B, the PM upon treatment of CHAPS for 1 day still possessed the trimeric features, indicating the retention of the S-TGA-1 in the center of the bR trimer. The S-TGD-1 seemingly reached a steady state of one-third of its original concentration to maintain the integrity of the bR trimeric configuration in dPM. In addition to maintaining the structural stability of bR and PM, altering the lipid compositions in dPM could also change the photocycle kinetics of bR, especially PGP-Me, PGS, and S-TGD-1 (36,43).

Figure 3.

Mass spectra of lipids extracted from PM and the various dPMs. The injection volumes for each sample were 50 and 100 μL, which were associated with a dilution to 0.25× and 0.50× of its original concentrations, respectively. Red, orange, green, purple, pink, and gray symbols refer to BPG (760), PG (806), PGS (886), PGP-Me (900), GlyC (966), and S-TGD-1 (1218) lipids, respectively. The values in parentheses denote the corresponding m/z. These ion intensities were normalized with respect to their corresponding retinal concentrations in Fig. S3 and Table S1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

The relative intensities of the molecular ions of the lipids in dPM samples with respect to those in PM: (A) BPG, (B) PG, (C) PGS, (D) PGP-Me, (E) GlyC, and (F) S-TGD-1 lipids. The error bars were calculated from the values obtained from the four experiments in Fig. 3 and Table S3. To see this figure in colour, go online.

Quantitative correlation of the photocycle kinetics and the lipid compositions

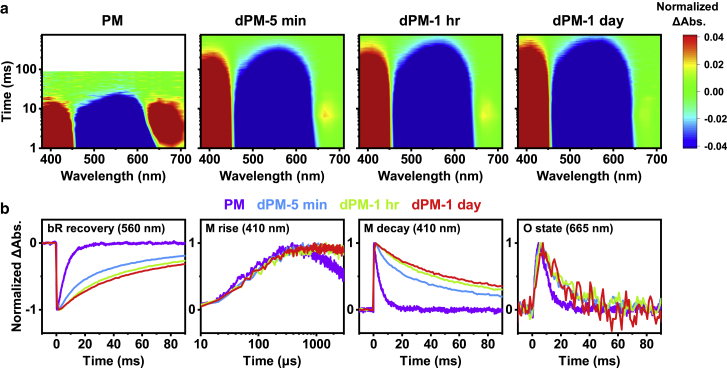

The repetition rates of the pulsed lasers for exciting the PM and dPM samples were confirmed beforehand to avoid overexcitation, as shown in Fig. S6. The contours of the time-resolved difference spectra upon excitation of PM and dPM are shown in Fig. 5 A. The photocycle was significantly retarded and the transient population of intermediate O at 665 nm decreased as the time of the CHAPS treatment increased. The corresponding temporal profiles of parent recovery and intermediates M and O are shown in Fig. 5 B. The rise of intermediate M, involving the proton migration from PRSB to Asp-85 in the protein interior (23,24,25), remained unchanged in dPM, suggesting that the entire structure of bR in dPM does not change significantly. In contrast, the decay of intermediate M and recovery of the parent gradually decelerated as the time of the CHAPS treatment of PM increased.

Figure 5.

(A) Two-dimensional contours of time-resolved difference spectra of PM and dPM. These contours were normalized with respect to their maximal depletion at 560 nm. (B) The normalized temporal profiles of the recovery of bR depletion at 560 nm, rise and decay of intermediate M at 410 nm and intermediate O at 665 nm upon 532-nm excitation. The concentrations of these samples were approximated as optical density (OD) = ca. 0.7 cm−1 at ca. 560 nm. The laser fluence was controlled at 0.48 mJ cm−2 pulse−1. To see this figure in color, go online.

In concomitance with the generation of intermediate M, a proton was released at the extracellular side (26) through a proton release group composed of several waters and residues at the extracellular proximity (23,60,61,62). Lateral proton migration along the membrane surface is faster than proton exchange with the bulk solution, ensuring the utilization of the chemical potential of the proton pump via the photocycle (63). Lipids, especially negatively charged lipids, are critical for the fast diffusion of protons along the surface due to their buffer capacity (64). Accordingly, if the negatively charged lipids, e.g., PGS and PGP-Me, are gradually removed during the delipidation by CHAPS, the proton release along the lipids via the sulfate and phosphate hydrophilic heads will be greatly suppressed due to the less-efficient proton relay capability. The cascading processes and the overall photocycle rate will be decelerated. The interconversions of the intermediates M→N→O were proposed to be reversible (23,25). Thus, if the lifetime of the intermediate M increases, the possibility to undergo the backward reaction without passing through intermediate O also increases, in concomitance with the reduced population of intermediate O. Moreover, the bRs in dPM samples with the native lipids mostly removed can still undergo conventional photocycle, with a slightly retarded kinetics of intermediate O, as shown in Fig. 5 B. Interestingly, the apparent rates of recovery of parent and the decay of intermediate M, and the transient population of intermediate O, significantly coincided with the composition percentiles of the negatively charged lipids PGS and PGP-Me, shown in Figs. 6, A, B, and C, respectively, determinatively quantifying the correlation between the proton pump and the negatively charged lipids. Joshi et al. also observed the recovery of the photocycle activity of monomerized bR using PGP (36).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the lipid contents and (A) the apparent recovery rate of photocycle, (B) the apparent decay rate of intermediate M, and (C) the transient population of intermediate O of the different samples. The apparent rates denote the reciprocals of the times required for the 90% recovery of photocycle and the 90% decay of intermediate M from Fig. 5B. The lipid ratios refer to the weighted intensities of the molecular ions of the PGS (green) and PGP-Me (purple) in dPM samples with respect to PM from Fig. 4. To see this figure in color, go online.

In addition to the roles of the negatively charged lipids, the removal of neutral lipid squalene might also influence the photocycle kinetics of dPM. Joshi et al. (36) have demonstrated that the omission of PGP-Me produced a profound diminution in restoration of lost photocycle behavior, whereas the omission of squalene, glycolipid sulfate, or PG had minimal effect. Moreover, they also demonstrated that full reconstitution can be obtained with PGP-Me alone at very high levels and the addition of squalene to suboptimal levels of PGP-Me also induces complete reconstitution. Accordingly, the roles of PGP-Me might be more predominant in the bR photocycle activity, in concomitance with the satisfactory coincidence of the residual amounts of PGP-Me in dPM and the corresponding photocycle kinetics, as shown in Fig. 6, even the amounts of squalene in dPM were not well quantified in this work.

Conclusion and biological implication

Numerous studies have been performed to study the roles of lipids in the photocycle kinetics of bR, such as the addition of extra lipids in the reconstituted bR (4,14,36,37,38) and lipid composition-controlled lipid nanodiscs (39,40,41). In addition to spectroscopy methods, x ray (12) and neutron diffraction (17) techniques have been utilized to determine the geometrical alignment of the lipids in the PM. However, it has been challenging to simultaneously quantify the lipid compositions and the concomitant photocycle properties, in terms of kinetics and transient populations of the intermediates. In this work, taking advantage of previous knowledge of PM (5,12,13,17), we incorporated mass spectroscopy and optical detection to investigate the lipid compositions and the concomitant photocycle kinetics of bR in various dPMs. Moreover, the extracted retinal concentration of each dPM sample was used to normalize the signal intensity of the m/z of the lipids, allowing us to compare the lipid compositions of the different samples. The rates of lipid removal can be qualitatively determined in the following fashion: BPG ≈ GlyC < S-TGD-1 ≈ PG < PGP-Me ≈ PGS. In addition, the great coincidence between the photocycle kinetics and the composition percentiles of two negatively charged lipids, PGS and PGP-Me, in dPM provides insight into the correlation between the individual lipids and their roles in the photocycle. In a practical application, the “top-down” strategy upon gradual strip-off of the lipids from the native conditions coupled with the mass spectrometry and spectroscopic methods simultaneously could be a better way to track the lipid-protein interaction strengths and the concomitant biological activity.

Associated content

Supporting information

The experimental setup of transient difference absorption spectroscopy (Fig. S1), absorption spectra of the retinal extracts from PM and dPM (Fig. S2), elution profiles of the retinals probed at 386 nm (Fig. S3) and the corresponding concentrations (Table S1) in dPM samples, mass spectra of lipids extracted from PM using different injection volumes and dilution factor (Fig. S4) and corresponding intensities (Table S2), the relative molecular ion intensities of the native lipids in dPM with respect to PM (Table S3), distribution of the hydrophobicity of bacteriorhodopsin (Fig. S5), and repetition rates of excitation laser for different samples (Fig. S6 and Table S4) are supplied as supporting material.

Author contributions

Y.-R.Z. performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. T.-Y.Y. and L.-K.C. designed the research, contributed analytical tools, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan and Academia Sinica (MOST 108-2113-M-007-001; MOST 109-2628-M-007-004-MY3 [to L.-K.C.] and AS-CDA-109-M03; MOST 110-2113-M-001-056 [to T.-Y.Y.]).

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: John C. Conboy.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.04.022.

Contributor Information

Tsyr-Yan Yu, Email: dharmanmr@gate.sinica.edu.tw.

Li-Kang Chu, Email: lkchu@mx.nthu.edu.tw.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Lozier R.H., Bogomolni R.A., Stoeckenius W. Bacteriorhodopsin: a light-driven proton pump in Halobacterium halobium. Biophys. J. 1975;15:955–962. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(75)85875-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemke H.-D., Oesterhelt D. Lysine 216 is a binding site of the retinyl moiety in bacteriorhodopsin. FEBS Lett. 1981;128:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stockburger M., Klusmann W., et al. Peters R. Photochemical cycle of bacteriorhodopsin studied by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1979;18:4886–4900. doi: 10.1021/bi00589a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dracheva S., Bose S., Hendler R.W. Chemical and functional studies on the importance of purple membrane lipids in bacteriorhodopsin photocycle behavior. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:209–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corcelli A., Lattanzio V.M.T., Fanizzi F., et al. Lipid–protein stoichiometries in a crystalline biological membrane: NMR quantitative analysis of the lipid extract of the purple membrane. J. Lipid Res. 2002;43:132–140. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2275(20)30196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson R., Unwin P.N.T. Three-dimensional model of purple membrane obtained by electron microscopy. Nature. 1975;257:28–32. doi: 10.1038/257028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kushwaha S.C., Kates M., Stoeckenius W. Comparison of purple membrane from Halobacterium cutirubrum and Halobacterium halobium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1976;426:703–710. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(76)90135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushwaha S.C., Kates M., Martin W.G. Characterization and composition of the purple and red membrane from Halobacterium cutirubrum. Can. J. Biochem. 1975;53:284–292. doi: 10.1139/o75-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corcelli A., Colella M., et al. Kates M. A novel glycolipid and phospholipid in the purple membrane. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3318–3326. doi: 10.1021/bi992462z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renner C., Kessler B., Oesterhelt D. Lipid composition of integral purple membrane by 1H and 31P NMR. J. Lipid Res. 2005;46:1755–1764. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m500138-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendler R.W., Barnett S.M., et al. Levin I.W. Purple membrane lipid control of bacteriorhodopsin conformational flexibility and photocycle activity: an infrared spectroscopic study. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:1920–1925. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cartailler J.-P., Luecke H. X-ray crystallographic analysis of lipid–protein interactions in the bacteriorhodopsin purple membrane. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003;32:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sternberg B., L’Hostis C., Watts A., et al. The essential role of specific Halobacterium halobium polar lipids in 2D-array formation of bacteriorhodopsin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1992;1108:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inada M., Kinoshita M., Matsumori N. Archaeal glycolipid S-TGA-1 is crucial for trimer formation and photocycle activity of bacteriorhodopsin. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020;15:197–204. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Essen L.-O., Siegert R., et al. Oesterhelt D. Lipid patches in membrane protein oligomers: crystal structure of the bacteriorhodopsin-lipid complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:11673–11678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palsdottir H., Hunte C. Lipids in membrane protein structures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weik M., Patzelt H., et al. Oesterhelt D. Localization of glycolipids in membranes by in vivo labeling and neutron diffraction. Mol. Cell. 1998;1:411–419. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendler R.W., Dracheva S. Importance of lipids for bacteriorhodopsin structure, photocycle, and function. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2001;66:1311–1314. doi: 10.1023/a:1013143621346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu K., Sun Y., et al. Zhang Y. The effect of lipid environment in purple membrane on bacteriorhodopsin. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2000;58:163–169. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(00)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birge R.R. Photophysics of light transduction in rhodopsin and bacteriorhodopsin. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng. 1981;10:315–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.10.060181.001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathies R.A., Brito Cruz C.H., et al. Shank C.V. Direct observation of the femtosecond excited-state cis-trans isomerization in bacteriorhodopsin. Science. 1988;240:777–779. doi: 10.1126/science.3363359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haupts U., Tittor J., Oesterhelt D. Closing in on bacteriorhodopsin: progress in understanding the molecule. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1999;28:367–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimányi L., Váró G., et al. Lanyi J.K. Pathways of proton release in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8535–8543. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothschild K.J. FTIR difference spectroscopy of bacteriorhodopsin: toward a molecular model. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1992;24:147–167. doi: 10.1007/bf00762674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Váró G., Lanyi J.K. Kinetic and spectroscopic evidence for an irreversible step between deprotonation and reprotonation of the Schiff base in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5008–5015. doi: 10.1021/bi00234a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan J.E., Vakkasoglu A.S., et al. Maeda A. Coordinating the structural rearrangements associated with unidirectional proton transfer in the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle induced by deprotonation of the proton-release group: a time-resolved difference FTIR spectroscopic study. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3273–3281. doi: 10.1021/bi901757y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phatak P., Ghosh N., et al. Elstner M. Amino acids with an intermolecular proton bond as proton storage site in bacteriorhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:19672–19677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810712105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerwert K., Souvignier G., Hess B. Simultaneous monitoring of light-induced changes in protein side-group protonation, chromophore isomerization, and backbone motion of bacteriorhodopsin by time-resolved Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:9774–9778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith S.O., Pardoen J.A., et al. Mathies R. Chromophore structure in bacteriorhodopsin's O640 photointermediate. Biochemistry. 1983;22:6141–6148. doi: 10.1021/bi00295a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ames J.B., Mathies R.A. The role of back-reactions and proton uptake during the N → O transition in bacteriorhodopsin’s photocycle: a kinetic resonance Raman study. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7181–7190. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukuda K., Ikegami A., et al. Kouyama T. Effect of partial delipidation of purple membrane on the photodynamics of bacteriorhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1997–2002. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukhopadhyay A.K., Bose S., Hendler R.W. Membrane-mediated control of the bacteriorhodopsin photocycle. Biochemistry. 1994;33:10889–10895. doi: 10.1021/bi00202a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng C.-W., Lee Y.-P., Chu L.-K. Study of the reactive excited-state dynamics of delipidated bacteriorhodopsin upon surfactant treatments. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012;539-540:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyes C.D., El-Sayed M.A. Proton transfer reactions in native and deionized bacteriorhodopsin upon delipidation and monomerization. Biophys. J. 2003;85:426–434. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74487-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Link S., et al. El-Sayed M.A. Comparison of the dynamics of the primary events of bacteriorhodopsin in its trimeric and monomeric states. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1557–1566. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)73925-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joshi M.K., Dracheva S., et al. Hendler R.W. Importance of specific native lipids in controlling the photocycle of bacteriorhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14463–14470. doi: 10.1021/bi980965j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z., Bai J., Xu Y. The effect of charged lipids on bacteriorhodopsin membrane reconstitution and its photochemical activities. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2008;371:814–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawatake S., Umegawa Y., et al. Sonoyama M. Evaluation of diacylphospholipids as boundary lipids for bacteriorhodopsin from structural and functional aspects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:2106–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee T.-Y., Yeh V., et al. Yu T.-Y. Tuning the photocycle kinetics of bacteriorhodopsin in lipid nanodiscs. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1899–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kao Y.-M., Cheng C.-H., et al. Chu L.-K. Photochemistry of bacteriorhodopsin with various oligomeric statuses in controlled membrane mimicking environments: a spectroscopic study from femtoseconds to milliseconds. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:2032–2039. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b01224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang H.-Y., Syue M.-L., et al. Chu L.-K. Influence of lipid compositions in the events of retinal Schiff base of bacteriorhodopsin embedded in covalently circularized nanodiscs: thermal isomerization, photoisomerization, and deprotonation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:9123–9133. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b07788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukhopadhyay A.K., Dracheva S., Hendler R.W., et al. Control of the integral membrane proton pump, bacteriorhodopsin, by purple membrane lipids of Halobacterium halobium. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9245–9252. doi: 10.1021/bi960738m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corcelli A., Lobasso S., et al. Dencher N.A. Glycocardiolipin modulates the surface interaction of the proton pumped by bacteriorhodopsin in purple membrane preparations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2007;1768:2157–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dencher N.A., Heyn M.P. Formation and properties of bacteriorhodopsin monomers in the non-ionic detergents octyl-β-D-glucoside and Triton X-100. FEBS Lett. 1978;96:322–326. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naito T., Kito Y., et al. Hamanaka T. Retinal-protein interactions in bacteriorhodopsin monomers, dispersed in the detergent L-1690. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1981;637:457–463. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(81)90051-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szundi I., Stoeckenius W. Effect of lipid surface charges on the purple-to-blue transition of bacteriorhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:3681–3684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnamani V., Hegde B.G., et al. Lanyi J.K. Secondary and tertiary structure of bacteriorhodopsin in the SDS denatured state. Biochemistry. 2012;51:1051–1060. doi: 10.1021/bi201769z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan E.H.L., Birge R.R. Correlation between surfactant/micelle structure and the stability of bacteriorhodopsin in solution. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2385–2395. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(96)79806-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milder S.J., Thorgeirsson T.E., et al. Kliger D.S. Effects of detergent environments on the photocycle of purified monomeric bacteriorhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1751–1761. doi: 10.1021/bi00221a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu L.-K., El-Sayed M.A. Bacteriorhodopsin O-state photocycle kinetics: a surfactant study. Photochem. Photobiol. 2010;86:70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chu L.-K., El-Sayed M.A. Kinetics of the M-intermediate in the photocycle of bacteriorhodopsin upon chemical modification with surfactants. Photochem. Photobiol. 2010;86:316–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oesterhelt D., Stoeckenius W. [69] Isolation of the cell membrane of Halobacterium halobium and its fractionation into red and purple membrane. Meth. Enzymol. 1974;31:667–678. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)31072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeh V., Lee T.-Y., et al. Yu T.-Y. Highly efficient transfer of 7TM membrane protein from native membrane to covalently circularized nanodisc. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13501. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31925-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heyn M.P., Bauer P.-J., Dencher N.A. A natural CD label to probe the structure of the purple membrane from Halobacterium halobium by means of exciton coupling effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1975;67:897–903. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(75)90761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becher B., Ebrey T.G. Evidence for chromophore-chromophore (exciton) interaction in the purple membrane of Halobacterium halobium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1976;69:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(76)80263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muccio D.D., Cassim J.Y. Interpretation of the absorption and circular dichroic spectra of oriented purple membrane films. Biophys. J. 1979;26:427–440. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(79)85263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freedman K.A., Becker R.S. Comparative investigation of the photoisomerization of the protonated and unprotonated n-butylamine Schiff bases of 9-cis-11-cis-13-cis-and all-trans-retinals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:1245–1251. doi: 10.1021/ja00266a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luecke H., Schobert B., et al. Lanyi J.K. Structure of bacteriorhodopsin at 1.55 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;291:899–911. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Catucci L., Lattanzio V.M.T., et al. Corcelli A. Role of endogenous lipids in the chromophore regeneration of bacteriorhodopsin. Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;63:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balashov S.P., Imasheva E.S., et al. Crouch R.K. Glutamate-194 to cysteine mutation inhibits fast light-induced proton release in bacteriorhodopsin. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8671–8676. doi: 10.1021/bi970744y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garczarek F., Gerwert K. Functional waters in intraprotein proton transfer monitored by FTIR difference spectroscopy. Nature. 2006;439:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature04231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown L.S., Sasaki J., et al. Lanyi J.K. Glutamic acid 204 is the terminal proton release group at the extracellular surface of bacteriorhodopsin. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27122–27126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heberle J., Riesle J., et al. Dencher N.A. Proton migration along the membrane surface and retarded surface to bulk transfer. Nature. 1994;370:379–382. doi: 10.1038/370379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grzesiek S., Dencher N.A. Dependency of ΔpH-relaxation across vesicular membranes on the buffering power of bulk solutions and lipids. Biophys. J. 1986;50:265–276. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(86)83460-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.