SUMMARY

Arid ecosystems cover ∼40% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface and store a high proportion of the global nitrogen (N) pool. They are low-productivity, low-biomass, and polyextreme ecosystems, i.e., with (hyper)arid and (hyper)oligotrophic conditions and high surface UV irradiation and evapotranspiration. These polyextreme conditions severely limit the presence of macrofauna and -flora and, particularly, the growth and productivity of plant species. Therefore, it is generally recognized that much of the primary production (including N-input processes) and nutrient biogeochemical cycling (particularly N cycling) in these ecosystems are microbially mediated. Consequently, we present a comprehensive survey of the current state of knowledge of biotic and abiotic N-cycling processes of edaphic (i.e., open soil, biological soil crust, or plant-associated rhizosphere and rhizosheath) and hypo/endolithic refuge niches from drylands in general, including hot, cold, and polar desert ecosystems. We particularly focused on the microbially mediated biological nitrogen fixation, N mineralization, assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reduction, and nitrification N-input processes and the denitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) N-loss processes. We note that the application of modern meta-omics and related methods has generated comprehensive data sets on the abundance, diversity, and ecology of the different N-cycling microbial guilds. However, it is worth mentioning that microbial N-cycling data from important deserts (e.g., Sahara) and quantitative rate data on N transformation processes from various desert niches are lacking or sparse. Filling this knowledge gap is particularly important, as climate change models often lack data on microbial activity and environmental microbial N-cycling communities can be key actors of climate change by producing or consuming nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent greenhouse gas.

KEYWORDS: biogeochemistry, desert, drylands, soils, biological soil crusts, lithobiont, diazotrophy, nitrogen cycling

INTRODUCTION

Drylands represent ∼40% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, occur on all continents, and are expanding with climate change (1). Drylands are arid environments, i.e., they present an overall deficiency in water availability. The aridity index (AI), which is the ratio of precipitation (P) to potential evapotranspiration (PET), is used to subcategorize them into hyperarid (AI < 0.05), arid (0.05 < AI < 0.2), semiarid (0.2 < AI < 0.5), and dry subhumid (0.5 < AI < 0.65) drylands (Fig. 1). Drylands with an AI of <0.65 encompass various ecosystems such as scrublands, shrublands, grasslands, savannas, semideserts, and true deserts. In this context, it must be noted that most of the studies used in this review were conducted in environments ranging from semiarid to hyperarid zones. Deserts further can be subdivided into three distinct categories depending on their global climatic conditions: hot (mean annual temperature > 18°C), cold (mean annual temperature < 18°C), or polar (warmest month mean temperature < 10°C) deserts.

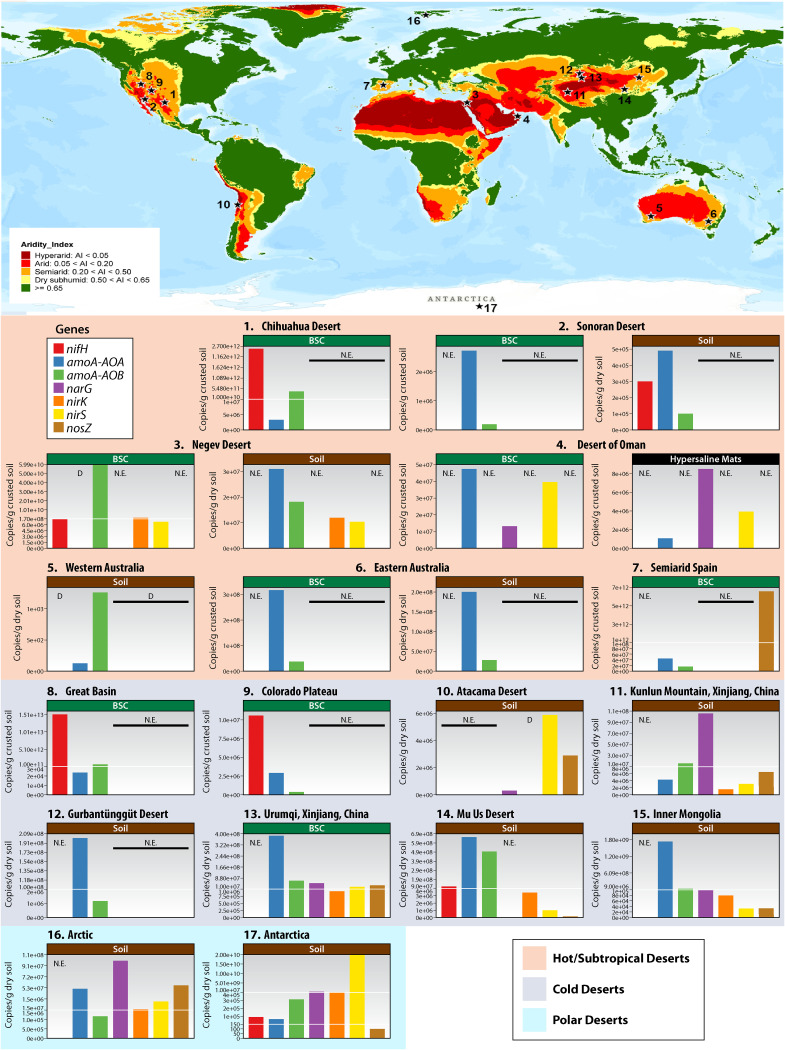

FIG 1.

Global aridity index (AI) map and microbial N-cycling gene abundances in various desert niches. The AI map (Esri grid) was obtained from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 10 arc min; https://data.apps.fao.org/map/catalog/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/221072ae-2090-48a1-be6f-5a88f061431a) and was visually represented with ArcGIS Pro. The AI classification is shown in the key on the figure. Hot, cold, and polar deserts where quantification of microbial cycling genes has been performed are indicated by numbers. Quantitative expression (qPCR) levels of functional genes involved in N cycling were collected from available sources (Table 3), and the average expression per gene (as copies g−1 dry/crusted soil) was calculated for each desert. Note that the y axes of the bar plots present different scales. “D” indicates genes detected by metagenomic and/or metatranscriptomic data without available quantitative expressions levels. N.E., not evaluated; BSC, biological soil crusts. References are given in Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Drylands are typically characterized by (i) low water availability, (ii) extreme diel and seasonal temperature ranges and fluctuations, (iii) high UV radiation, and (iv) low nutrient status (i.e., oligotrophy) (2). Due to these polyextreme conditions, microbial communities are most prevalent in islands of fertility, i.e., in specialized shielded niches such as biological soil crusts (BSCs), plant-associated environments (e.g., rhizospheres and rhizosheath/root systems), and lithic habitats, i.e., hypoliths and (chasmo/crypto)endoliths, which are microbial communities found under the ventral surface of translucent rocks or within the fissures and pores of rocks, respectively (3–6). Furthermore, since plant productivity is both temporally and spatially limited in arid ecosystems, microbial communities are the principal drivers of primary production and nutrient cycling (4, 5, 7, 8).

Nitrogen (N) is an element essential for life. Yet, despite amounting to some 4 × 1018 kg N in the form of dinitrogen (N2) in the atmosphere (i.e., 78% of the total mean mass of the atmosphere, which has been estimated to represent 5.148 × 1018 kg) (9), nitrogen is often a limiting factor for terrestrial and aquatic ecosystem productivity (10, 11). Oceans contain approximately 1 Tg (1 × 109 kg) of N, 94% as biounavailable N2 and much of the rest as bioavailable nitrate (NO3−) (12). The N lithospheric content has been estimated to range between 133 × 103 and 140 × 103 Tg N in the top 100 cm of the terrestrial surface (13). Deserts have been estimated to store 95 × 103 Tg of N (14), i.e., more than half of the terrestrial N pool. Recent evidence suggests that drylands store an even greater amount of N in large subterranean nitrate (NO3−) pools, representing ∼104 kg N ha−1 (15, 16). Extrapolated to the global desert pavement surface area, this would represent a 5-fold increase in total N storage in desert soils. Consequently, models suggest that 80% of the global nitrate pool (i.e., 460 Tg) is stored in deserts (17). However, due to the combination of water scarcity and high soil salinity, much of this pool is unavailable to productive guilds, i.e., plants and microbial communities (16). In drylands, N is considered the second most important limiting factor after water; i.e., it is the most limiting nutrient (18–20).

As in other environments, the arid land microbial communities are critical for the completion of the biogeochemical N cycle, as specific taxa are the sole mediators of key processes that control the quantities of bioavailable ammonium/ammonia (NH4+/NH3) and nitrate (NO3−). These include biological N fixation (BNF) and nitrification, which are processes by which N is added to the environment (Fig. 2), and denitrification, a process by which N is lost and which can lead to the production of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O) (Fig. 2). Global annual terrestrial microbial production of N2O has been estimated to amount to 7.2 to 13.2 Tg N year−1, of which drylands contribute 3 × 10−12 to 49 × 10−12 Tg N ha−1 year−1 (21). With drylands covering ∼6 billion hectares globally (22), this represents 1.8 × 10−5 to 2.94 × 10−3 Tg N year−1.

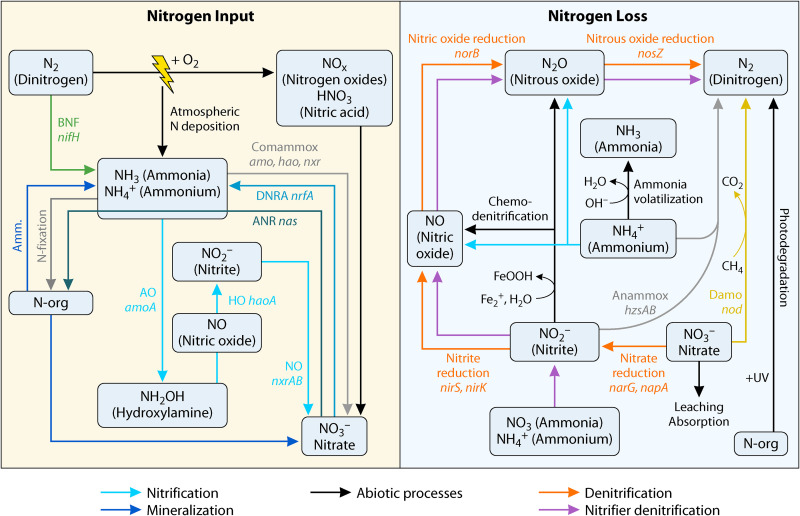

FIG 2.

Biogeochemical cycle of nitrogen. Denitrification encompasses the nitrate, nitrite, nitric oxide, and nitrous oxide reduction reactions, and nitrification encompasses the aerobic ammonia, hydroxylamine, and nitrite oxidation reactions. Amm., ammonification; AO, ammonia oxidation; BNF, biological nitrogen fixation; DNRA, dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium; HO, hydroxylamine oxidation; NO, nitrate oxidation; anammox, anaerobic ammonium oxidation; comammox, complete ammonia oxidation; Damo, denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation. Microbial genes relevant to each process are indicated. N-Org, organic nitrogen. The NH4+/NH3 equilibrium in the environment is controlled by many parameters. Ammonia volatilization has notably been positively correlated to soil pH, CaCO3, and salt contents and negatively to soil cation exchange capacity, organic matter, and clay contents (323).

The inherent oligotrophy of dryland ecosystems makes them particularly vulnerable to the alterations of the global N cycle by anthropogenic activities and global climate change (23). As the acceleration of desertification processes is an inevitable consequence of current anthropogenic activities (24), it becomes increasingly important to understand the global functioning of arid ecosystems. Here, we describe and discuss the abiotic and microbial processes that contribute to N cycling in the various niches of arid environments.

NITROGEN INPUT PROCESSES IN ARID ENVIRONMENTS

Nitrogen is the principal limiting factor in the net primary productivity (NPP) of most terrestrial ecosystems (19), the exception being arid ecosystems, where water availability is the dominant driver of NPP (18–20). In natural ecosystems, as opposed to engineered/man-made ecosystems like wastewater treatment plants or fertilized fields, three processes are responsible for de novo nitrogen inputs: (i) atmospheric wet (precipitation) as well as dry gaseous (NOx, HNO3, and NH3) and dust sources, (ii) lightning, and (iii) biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) (Fig. 2) (25–29).

BNF is by far the most dominant process, estimated to be responsible for over 97% of the terrestrial N input in pristine terrestrial systems (27), representing at a global scale from 52 to ∼195 Tg N year−1 (30, 31). This proportion is also observed in drylands, even though barren lands have the lowest terrestrial BNF globally (31, 32). In desert and arid shrubland ecosystems, BNF has been estimated to contribute 4.8 to 10.8 kg N ha−1 year−1 and 9.4 to 33.9 kg N ha−1 year−1, respectively (30). This is significantly higher than BNF in cold boreal forest ecosystems (i.e., 1.5 to 2.0 kg N ha−1 year−1) (30). This suggests that polar and cold desert BNF is rather low due to lower biological activities (33). Furthermore, it indicates that in dryland ecosystems, BNF is favored in less arid drylands, i.e., increases with vegetation cover. A recent meta-analysis at the Latin American scale confirms this view (34).

Other microbially mediated processes also participate in the input of bioavailable N, particularly through the recycling of the soil N pool via various biogeochemical transformations: ammonification, nitrification, and dissimilatory and assimilatory nitrate reduction (Fig. 2). These are particularly important, as organic N represents over 99% of the total N in most environments, including drylands (35).

Abiotic Nitrogen Deposition and Fixation

Atmospheric nitrogen deposition results from three abiotic processes: gaseous (NOx, NO2, HNO3, and NH3) and dust deposition (dry process), precipitation (wet process), and nitrogen fixation by lightning (30, 36, 37). On a global scale, lightning-derived N fixation, in the form of nitrogen oxides (NOx), is estimated to be ∼7 Tg N year−1. This is particularly important around the tropics (36, 38, 39), where most deserts are located. However, satellite data clearly demonstrate that for most deserts, particularly the Sahara and Central Australian deserts, this form of N input is negligible, most probably due to the rarity of storms in such environments (38, 40). For the same reason, atmospheric (wet) N deposition—in the reduced ammonium NH4+ and/or oxidized nitrate (NO3−) forms—is also temporally limited in drylands but, in contrast to lightning-based N fixation, is not negligible. The wet deposition of ammonium (NH4+) in drylands is highly correlated with the magnitude of precipitation events, with concentrations often exceeding those of nitrate (NO3−) by up to 50% (41–43). In dryland soils, NH4+, rather than being directly taken up by plants, is usually nitrified into nitrate, which can decrease soil pH (44). Ultimately, a large percentage (>40%) of the wet deposited ammonium/nitrate is retained by the vegetation and therefore improves plant biomass production in drylands (43).

Globally, the total N deposition is estimated to range between 125 and 132 Tg N year−1 (45) and varies between ∼0.5 and ∼7.5 kg N ha−1 year−1 in most drylands (46). However, it is desert/dryland dependent. In the Chihuahan Desert (USA), between 1989 and 2004, atmospheric ammonium and nitrate deposition were positively correlated to precipitation and estimated to represent 1.2 kg ha−1 year−1 and 0.9 kg ha−1 year−1, respectively (37). In contrast, in an area spanning the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts (USA), total atmospheric N deposition, which ranged from 2.8 to 14.4 kg N ha−1 year−1, was not correlated with annual precipitation (47). This apparent dichotomy was also observed at two sites in the Negev Desert (less than 50 km apart) which received similar total N atmospheric inputs (∼0.84 kg N ha−1 year−1). However, one received more atmospheric N deposition during the dry season and the other during the rainy season (48). Together, this clearly demonstrates that local climatic regimes should be monitored when assessing abiotic nitrogen deposition in deserts. For example, the coastal regions of the Atacama (Chile) and Namib (Namibia) Deserts are subjected to regular fog events, with fog water nitrate concentrations ranging from 17.8 to 27.8 mg L−1 and 36.2 to 71.2 mg L−1, respectively (46, 49, 50). In the Namib Desert, fog water deposition can range from 3 mm (112 km from the coast) to 184 mm (33 km inland) annually (51). In the Atacama Desert, fog water deposition is particularly important in the first 10 km from the Pacific Ocean and has been estimated to represent ∼25 L m−2 (52). Consequently, this provides a significant N input in the form of nitrate deposition, ranging from 1.1 to 2.1 kg ha−1 year−1 to 66.6 to 131.0 kg ha−1 year−1 and from 0.5 to 0.7 kg ha−1 year−1 in the Namib and Atacama Deserts, respectively. As nitrate is deposited with water, it becomes immediately bioavailable, which explains the rather important microbial and vegetation life in the fog-influenced zones of these deserts (53–56).

Human activities have increased the atmospheric N pool by particularly intensifying atmospheric N deposition, thus altering the global N biogeochemical cycle (57). In the Chihuahan Desert, N deposition rates have increased between 1989 and 2004 by 0.049 kg ha−1 year−1 (37). In this context, the expansion of urban areas in the vicinity of drylands will also locally impact atmospheric N deposition (47, 58). In the Sonoran Desert, atmospheric N deposition rates within metropolitan Phoenix and in the nearby desert have been shown to represent 7.2 (±0.4) and 6.1 (±0.3) kg N ha−1 year−1, respectively, over a 9-year period (2006 to 2015). It is difficult to predict how this increase in N deposition will influence local productivity and microbially mediated N cycling in drylands, since the potential use of N is ultimately linked to the availability of water, which is predicted to remain a scarce resource in most drylands with global climate change (59). Nevertheless, precipitation increases the availability of N in these environments (60, 61). This has been shown to decrease plant community diversity and favor nonnative grass growth (57, 61). Similarly, it certainly will impact the structure and function of dryland (N-cycling) microbial communities, particularly of those interacting with the native plants. This is further supported by a meta-analysis, based on 454 experiments, which suggests edaphic microbial biomass increases in grasslands and decreases in deserts after N addition, whereas fungal biomass decreases in both arid biomes (62). In the Gurbantünggüt Desert (northwestern China), surface soil enzyme activities also varied after N addition (63). Together, this clearly shows that increasing atmospheric N deposition will modify dryland ecosystems’ functioning and their N biogeochemical cycling.

Biological Nitrogen Fixation

Prokaryotic N fixers in drylands.

The phylogenetic affiliations and abundances of environmental diazotrophic taxa are generally evaluated using the nitrogenase nifH gene (Fig. 1 and 2) (64–68). However, for accurate diversity analyses of N-fixing taxa, the use of multiple primer sets and/or a combination of approaches is recommended (68, 69). For example, in a global survey of hypolithic communities, diazotrophic cyanobacteria (e.g., Nostoc spp.) were detected using the 16S rRNA gene but not with nifH PCR primers known to amplify cyanobacterial nifH genes (68). Similarly, nitrogen-fixing genes were marginally detected in shotgun metagenomes from hypolithic and endolithic communities (70, 71), whereas microscopic observations (72) and stable isotope analyses (73) clearly supported the presence of diazotrophic microorganisms in these niche communities.

The capacity for diazotrophy is present in various branches of the bacterial and archaeal domains, particularly within the bacterial phyla Cyanobacteria, Actinomycetota, Bacillota, and Pseudomonadota and the Euryarchaeota archaeal phylum (30, 74–77). Despite being a highly energy-demanding process (16 ATP molecules and 8 electrons per N2 molecule reduced) (64), N-fixing representatives from all of these phyla have been detected in hot and cold desert edaphic and cryptic niche communities (Fig. 3; Table 1) (6, 65, 67, 68, 70, 78–84). Environmental N fixation is most commonly quantified using the acetylene reduction assay (ARA), which measures nitrogenase activity via the reduction of acetylene to ethylene (85), and 15N2 incorporation rate measurements (86) (Table 1).

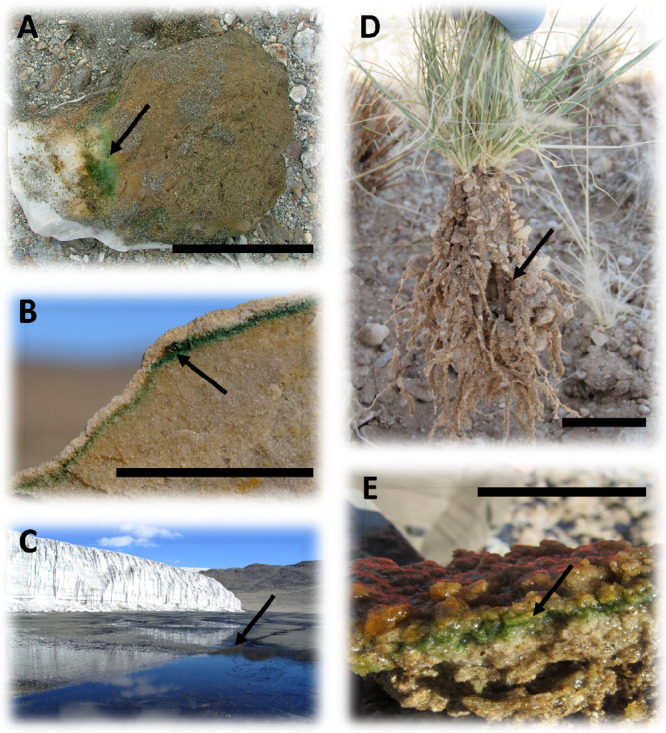

FIG 3.

Cryptic and productive desert niches colonized by free-living and symbiotic N fixers. (A) Large quartz hypolith from the McMurdo Dry Valleys (East Antarctica). The ventral surface of the quartz rock shows extensive hypolithic biomass. (B) Cryptoendolithic community in Antarctic Beacon sandstone. The green layer is dominated by Cyanobacteria. (C) Antarctic glacial runoff pan with extensive Nostoc species growth. (D) Rhizosheath-root structure of Stipagrostis ciliata (Namib Desert). (E) Namib Desert stratified salt pan microbial mat. Black bars, 3 cm. Black arrows indicate the productive and N-fixing zone.

TABLE 1.

Microbial nitrogen fixation in hot and cold dryland/desert habitatsa

| Habitat type | Desert | Reference | Acetylene reduction assay rates | nifH detection and/or abundances | Diversity of diazotrophs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological soil crust | Canyonlands, Utah | 280 | Light crust: 0.13 ± 0.05 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE |

| Dark crust: 0.86 ± 0.26 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| Chihuahuan Desert | 309 | ∼40–100 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | Scytonema sp., Microcoleus steenstrupii, Microcoleus vaginatus, Pseudanabaena sp. | |

| 324 | Early successional crust: ∼3–20 μmol C2H4 m−2 day−1 | NE | NE | ||

| Late successional crust: ∼10–100 μmol C2H4 m−2 day−1 | NE | NE | |||

| 130 | 0.04–12.69 nmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 20 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| 131 | Lichen crust: ∼0–100 μmol N m−2 h−1 | 5.13 × 1012 copies g−1 | Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp. | ||

| Light crust: ∼0–50 μmol N m−2 h−1 | 2.52 × 1012 copies g−1 | Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp. | |||

| 106 | Poorly developed crust (Microcoleus spp. dominated): ∼5 μmol m−2 h−1 | 1.8 × 106 copies g−1 soil | Microcoleus steenstrupii, Microcoleus vaginatus | ||

| Mature crust (mixed cyanobacteria, lichen, and moss): ∼12 μmol m−2 h−1 | 3.4 × 107 copies g−1 soil | Microcoleus steenstrupii, Chrococcidiopsis sp., Scytonema sp. | |||

| 103 | NE | D | nifH clusters S1 (29/121; Scytonema sp.), S2 (7/121; Scytonema hyalinum), T2 (4/121; Tolypothrix sp.), U1 (13/121), and U2 (52/121), other cyanobacterial nifH sequences (8/121), other bacterial nifH sequences (8/121) | ||

| 131 | Lichen crust: ∼0–100 μmol N m−2 h−1 | 5.13 × 1012 copies g−1 | Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp. | ||

| Light crust: ∼0–60 μmol N m−2 h−1 | 2.52 × 1012 copies g−1 | Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp. | |||

| Colorado Plateau | 309 | ∼30–50 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | Scytonema sp., Microcoleus steenstrupii, Microcoleus vaginatus, Pseudanabaena sp. | |

| 324 | Early successional crust: ∼3–76 μmol C2H4 m−2 day−1 | NE | NE | ||

| Late successional crust: ∼18–107 μmol C2H4 m−2 day−1 | NE | NE | |||

| 325 | Lichen crust: 11.0 ± 5.7–57.9 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 326 | Cyanobacteria-dominated crust: ∼15–30 nmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | Microcoleus vaginatus, Scytonema myochrous | ||

| Lichen crust: ∼10–90 nmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | Collema tenax (Nostoc sp. as N-fixing phycobiont) | |||

| 91 | Light cyanobacterial crust: 0–0.80 nmol cm−2 h−1 | NE | Microcoleus vaginatus | ||

| Dark cyanobacterial crust: 0–5 nmol cm−2 h−1 | NE | Nostoc commune, Scytonema myochrous | |||

| Colema crust: 0–13 nmol cm−2 h−1 | NE | Collema sp. | |||

| 103 | NE | D | nifH clusters S1 (69/473; Scytonema sp.), S2 (62/473; Scytonema hyalinum), N1 (134/473; Nostoc sp.), N2 (28/473; Nostoc commune), and T1 (128/473; Spirirestis sp.), other cyanobacterial nifH sequences (17/473), other bacterial nifH sequences (83/473) | ||

| 106 | Poorly developed crust (Microcoleus spp. dominated): ∼2.5 μmol m−2 h−1 | 1.1 × 106 copies g−1 soil | Microcoleus steenstrupii, Phormidium murrayii, Phormodium sp., Microcoleus vaginatus | ||

| Mature crust (mixed cyanobacteria, lichen, and moss): ∼20 μmol m−2 h−1 | 2.0 × 107 copies g−1 soil | Microcoleus steenstrupii, Microcoleus sociatus, Phormidium spp., Scytonema sp. | |||

| 178 | Dark crust: 48.00 ± 9.31 μmol C2H2 reduced m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| Light crust: 6.53 ± 1.87 μmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| 98 | Collema-dominated biocrusts: 1.6 nmol C2H2 cm−2 h−1 | NE | Collema spp. | ||

| Squamarina lentigera-dominated biocrust: 0.2 nmol C2H2 cm−2 h−1 | NE | Squamarina lentigera | |||

| Gyalolechia desertorum-dominated biocrust: 0.4 nmol C2H2 cm−2 h−1 | NE | Gyalolechia desertorum | |||

| Great Basin Desert | 326 | ∼15–90 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| 327 | Ungrazed: 0.37–2.54 g N ha−1 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 132 | 4.3–72.2 nmol C2H4 m−2 s−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 328 | 10.5–84.0 nmol C2H4 m−2 s−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 131 | Light crust: ∼0–200 μmol N m−2 h−1 | 3.94 × 1012 copies g−1 | Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp. | ||

| Dark crust: ∼0–370 μmol N m−2 h−1 | 2.63 × 1013 copies g−1 | Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp. | |||

| Gurbantunggut Desert | 110 | Cyanobacterial crust: 2.26–9.81 × 103 nmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| Lichen crust: 6.54 × 102–9.06 × 103 nmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| Moss crust: 6.38 × 102–2.03 × 103 nmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| Kalahari Desert | 329 | 0.6–6.8 nmol C2H4 nmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| Mojave Desert | 309 | ∼30–200 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | Scytonema sp., Microcoleus steenstrupii, Microcoleus vaginatus, Pseudanabaena sp. | |

| 135 | Lichen crust: 11.3 ± 7.7–25.2 ± 11.7 μmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| Nonlichen crust: 0–27.0 ± 26.3 μmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| Negev Desert | 330 | 34 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| 331 | Cyanobacterial crust: 1.0–1.2 g N m−2 yr−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 332 | Cyanobacterial crust (n = 4): NE | 6.7 × 107–3.4 × 108 copies cm−2 | Microcoleus vaginatus (4/4), Scytonema sp. (3/4), Phormidium sp. (1/4), Nostoc sp. (1/4) | ||

| Moss crust (n = 1): NE | 1.6 × 108 copies cm−2 | Microcoleus vaginatus, Nostoc sp. | |||

| Omani Desert | 104 | 58.5 ± 2.6 mmol C2H4 reduced m−2 h−1 (or 183–258 mg N m−2 h−1) | NE | Microcoleus vaginatus, Nostoc sp., Scytonema sp., Brasilonema sp., Petalonema sp. | |

| Sahel Desert | 133 | 0.001–4.2 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 | NE | Nostoc sp., Scytonema javancum | |

| Sonoran Desert | 309 | ∼50–100 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | Scytonema sp., Microcoleus steenstrupii, Microcoleus vaginatus, Pseudanabaena sp. | |

| 333 | 78 nmol C2H4 cm−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 107 | NE | NE | Synechococcus sp., Microcoleus vaginatus, Microcoleus steenstrupi, Chroococcidiopsis sp., Cylindrospermum sp., Scytonema hyalinum | ||

| Tengger Desert | 111 | Cyanobacterial-algal crust: 16.6 mmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| Lichen crust: 6.9 mmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| Moss crust: 2.6 mmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |||

| 334 | Moss and bacterial BSC: NE | Moss (n = 6): 0.0021 ± 0.0007 | NE | ||

| Bacterial (n = 6): 0.0060 ± 0.0031 | NE | ||||

| Soil | Roxby Downs, Australia | 125 | NE | 6.4% (±1.2%) total predicted genes in metagenomes (n = 8) and 3.4% (±2.5%) in metatranscriptomes (n = 2) | Archaea (“Candidatus Methanoperedens sp.,” Methanobacterium sp., Methanolobus sp., Methanosarcina spp.); Bacillota (Sporobacer sp., Clostridum spp., Eubacterium sp., Marvinbryantia spp., Lachnoclostridium spp., Paenibacillus sp., Carboxydocella spp., Desulfotomaculum sp., Propionispira sp., Desulfitobacterium spp., Butyrivibrio spp.); Spirochaetota (Treponema sp.); Alphaproteobacteria (Skermanella sp., Neorhizobium sp., Azospirillum spp., Phaeospirillum sp., Bradyrhizobium sp., Rhizobium spp., Nitrospirillum sp., Sphingomonas sp., Methylocapsa sp., Rhodopila sp., Rhodovulum sp., Rhodopseudomonas sp., Aurantimonas sp., Komagataeibacter sp., Methylocella sp.); Betaproteobacteria (Derxia sp., Dechloromonas sp., Rubrivivax sp., Herbaspirillum spp.), Gammaproteobacteria (Alteromonadales, Beggiatoa sp., Neiella sp., Halorhodospira sp., Methylovulum sp., Agarivorans sp., Pseudomonas sp., Solimonas sp.); Deltaproteobacteria (Geothermobacter sp., Desulfuromusa sp., Dissulfuribacter sp., Anaeromyxobacter sp.); Bacteroidota (Draconibacterium sp., Labilibacter sp.); Chloroflexota (Oscillochloris sp., Roseiflexus sp.); Cyanobacteria (Trichormus sp., Nostoc spp., Calothrix sp., Chlorogloeopsis sp., Cylindrospermum sp., Fischerella spp., Cylindrospermopsis sp., Nodularia sp., Tolypothrix sp., Kamptonema sp.); Actinomycetota (Propionibacterium sp.) |

| Gobi Desert | NE | 1.8% total predicted genes | Archaea (“Candidatus Methanoperedens sp.”); Bacillota (Sporobacer sp., Clostridum spp., Eubacterium sp., Marvinbryantia sp., Lachnoclostridium spp., Carboxydocella spp., Moorella sp., Megasphaera sp., Butyrivibrio spp., Acetobacterium sp.); Alphaproteobacteria (Rhodoblastus sp., Cohaesibacter sp.), Betaproteobacteria (Rhodocyclales spp.); Gammaproteobacteria (Succinivibrio sp., “Candidatus Contendobacter sp.,” Ectothiorhodospira sp., Halorhodospira sp.) | ||

| Mojave Desert | NE | 2.4% total predicted genes | Bacillota (Sporobacer sp., Clostridum spp., Eubacterium sp., Marvinbryantia sp., Lachnoclostridium spp.); Planctomycetota (Blastopirellula sp.); Gammaproteobacteria (Allochromatium sp., Ectothiorhodospira sp., Halorhodospira sp.) | ||

| Northeastern desert region of Egypt | 335 | NE | 2.51 × 104 copies g−1 soil | Alphaproteobacteria (Rhizobium sp., Bradyrhizobium sp.), Betaproteobacteria (Ideonella sp., Derxia sp., Dechloromonas sp., Zoogloea sp.), Gammaproteobacteria (Azomonas sp.), Bacilli (Paenibacillus sp.) | |

| Gurbantunggut Desert | 171 | NE | NE | Microcoleus sp., Chroococcidiopsis sp., Phormidium sp., Nostoc spp. | |

| Namib Desert | 79 | NE | D | Pseudomonadota | |

| 123 | NE | NE | Nostocales | ||

| 124 | NE | D | NE | ||

| 125 | NE | 2.9% total predicted genes | Archaea (“Candidatus Methanoperedens sp.,” Methanobacterium sp.); Bacillota (Clostridum spp., Eubacterium sp., Marvinbryantia sp., Lachnoclostridium spp., Carboxydocella spp., Dethiosulfatibacter sp., Butyrivibrio sp.); Spirochaetota (Treponema sp.); Alphaproteobacteria (Sphingomonas sp.); Betaproteobacteria (Rhodocyclales spp.), Gammaproteobacteria (Marichromatium sp., Nitrincola sp., Agarivorans sp., Thiorhodospira sp.); Cyanobacteria (Trichormus sp.) | ||

| Mu Us Desert | 336 | NE | 1.3 × 107–2.0 × 108 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| Sonoran Desert | 337 | Undisturbed site: 2.4 ± 0.05 nmol C2H4 soil g−1 day−1 | 3.02 × 105 copies g−1 soil | Azospirillum sp., Rhizobium sp., Pseudomonas sp. | |

| Tengger Desert | 67 | Control site: 0.025 ± 0.008 mmol C2H4 m−2 h−1 | NE | Alphaproteobacteria (Mesorhizobium sp.), Epsilonproteobacteria (Arcobacter sp.), Cyanobacteria (Plectonema sp.), Verrucomicrobiota, Bacillota | |

| King Sejong Station and Cape Burk area (Antarctica) | 257 | NE | 4.0 × 104–1.4 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| Miers Valley (Antarctica) | 65 | ND (0/14) | NE | NE | |

| 83 | NE | D | Archaea, Actinomycetota, Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, Chlorobiota, Chloroflexota, Cyanobacteria, Bacillota, Spirochaetota, Bacteroidota, Fusobacteriota | ||

| Anchorage Islands (Antarctica) | 103 | NE | D | NE | |

| Anvers Island (Antarctica) | 338 | 12.31–59.32 μmol N m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| McKelvey Valley (Antarctica) | 78 | NE | D | Archaea, Actinomycetota, Cyanobacteria, Bacillota, Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, Spirochaetota | |

| 18 Antarctica soils | 120 | NE | 6 nif hits in 3/18 shotgun metagenomes | Cyanobacteria | |

| Hypolith | Namib Desert | 71 | NE | D | Cyanobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria |

| Qaidam Basin | 114 | NE | ND | Chroococcidiopsis sp., Phormidium sp., Micrococcus sp. | |

| Taklimakan Desert | 114 | NE | ND | Chroococcidiopsis sp., Phormidium sp. | |

| 68 | NE | D | nifH: Alphaproteobacteria (Rhodospirillales, Rhizobiales), Gammaproteobacteria (Pseudomonadales)/16S rRNA: 14.6% of the sequences, including Chroococcidopsis sp. and Phormidium sp. | ||

| Tibetan Plateau | 68 | NE | D | nifH: Alphaproteobacteria (Rhodospirillales, Rhizobiales), Betaproteobacteria (Burkholderiales)/16S rRNA: 18.4% of the sequences, including Chroococcidopsis sp. and Phormidium sp. | |

| Turpan Depression | 114 | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | ||

| McKelvey Valley (Antarctica) | 78 | NE | D | Archaea, Actinomycetota, Cyanobacteria, Bacillota, Nitrospirota, Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, Spirochaetota | |

| Miers Dry Valley (Antarctica) | 65 | 0.02–0.174 nmol N g−1 h−1 (6/12) | D | Cyanobacteria, Pseudomonadota | |

| 83 | NE | D | Archaea, Actinomycetota, Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, Chlorobiota, Chloroflexota, Cyanobacteria, Bacillota, Spirochaetota, Verrucomicrobiota | ||

| McMurdo Dry Valleys (Antarctica) | 68 | NE | D | nifH: Alphaproteobacteria (Rhizobiales), Betaproteobacteria (Burkholderiales)/16S rRNA: 5.3% of the sequences, including Phormidium sp. | |

| Arctic | 68 | NE | ND | 16S rRNA: 13.8% of the sequences, including Chroococcidopsis sp. and Phormidium sp. | |

| Endolith | 7 hot and 41 cold deserts | 112 | Detected (1 Antarctic/48) | NE | NE |

| Al-Jafr Basin Desert | 113 | NE | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |

| Mojave Desert | 113 | NE | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |

| Atacama Desert | 113 | NE | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |

| 70 | NE | ND | |||

| 119 | ND | NE | |||

| 339 | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |||

| McKelvey Valley | 78 | NE | D | Archaea, Actinomycetota, Cyanobacteria, Bacillota, Nitrospirota, Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, Gamma-, and Epsilonproteobacteria, Spirochaetota | |

| McMurdo Dry Valleys | 88 | Aerobic 20°C: 0.095–1.2 mol C2H4 μg Chla−1 g rock−1 h−1 | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |

| Aerobic 5°C: 0.099–2.1 mol C2H4 μg Chla−1 g rock−1 h−1 | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |||

| Anaerobic 20°C: 1.07–2.24 mol C2H4 μg Chla−1 g rock−1 h−1 | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. | |||

| Anaerobic 5°C: 1.5-2.95 mol C2H4 μg Chla−1 g rock−1 h−1 | NE | Chroococcidiopsis sp. |

D, detected; ND, not detected; NE, not evaluated.

Given the strictly anaerobic requirements for nitrogenase functioning, N-fixing bacteria are mainly obligate anaerobes or microaerophilic (i.e., able to live in environments with very low oxygen levels). Multicellular filamentous cyanobacteria have, however, evolved specific cells (heterocysts) which provide the anaerobic conditions suitable for nitrogenase activity in an otherwise aerobic system (87, 88). Over 100 heterocystous cyanobacterial genera have already been described (89). The heterocystous cyanobacteria Nostoc spp. have been detected in desert niches globally (Fig. 3C; Table 1). Nonheterocystous aerobic cyanobacteria also contribute significantly to N fixation (90). Among these, Microcoleus spp., Chroococcidiopsis spp., and Synechococcus spp. have been shown to be common in hot, cold, and polar desert microbial communities (68, 83, 91, 92) (Table 1). These N-fixing bacteria can be free-living (e.g., Microvirga spp.) or symbiotically associated with desert plants such as Acacia spp. and Stipagrostis spp. (e.g., Rhizobia, Bradyrhizobium, Frankia, and Azospirillum spp.) (6, 93). Other symbiotic associations with N-fixing microorganisms found in deserts include cyanolichens and chlorolichens which are obligate symbioses between cyanobacteria and fungi and between green algae and fungi, respectively (94–98) (Table 1).

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) in the different dryland niches. (i) Biological soil crusts (BSCs).

BSCs are complex microbial assemblages that can cover up to 70% of cold and hot desert soil surfaces (4, 99, 100). Diazotrophic communities associated with BSCs in desert ecosystems have been well characterized (Table 1). BSCs are typically dominated by cyanobacteria, most commonly by members of the diazotrophic genus Microcoleus, and include chlorophyte algae, heterotrophic bacteria, fungi, mosses, and lichens (4, 100, 101). BSCs may also contain N-fixing cyanolichens (e.g., Collema), chlorolichens (e.g., Gymnosoma desertorum), filamentous heterocystous (e.g., Anabaena spp., Nostoc spp., Scytonema spp.) and nonheterocystous (e.g., Microcoleus spp., Chroococcidiopsis spp.) cyanobacteria, as well as heterotrophic N-fixing bacteria (e.g., Azospirillum spp.) (91, 98, 102–105) (Table 1). BSC microbial assemblages and diazotrophic communities have been shown to vary spatially and temporally, depending on aridity and their developmental stages (100, 105–107). BSCs in hyperarid desert regions, which are characterized by very high evapotranspiration rates, typically do not contain either mosses or lichens (100, 106).

With both photosynthetic and diazotrophic capacities, BSCs constitute the dominant primary producers in plant-free desert ecosystems (108). Globally, desert BSCs show one of the highest N fixation rates of all terrestrial ecosystems, at around 7.6 kg N ha−1 year−1 and representing a global total of 107 Tg N year−1 (108, 109). As shown in Table 1, desert BSC N-fixing capacities vary widely, depending on location, developmental stage, and composition (91, 110, 111). This is particularly exemplified by a study on lichen-dominated Colorado Plateau BSCs, which have even been found to fix N2 at different rates depending on the dominant lichen (98). Using surface coverage metrics, the annual N fixation flux contributions for each lichen-dominated BSC species in the Colorado Plateau were estimated to be 1.17, 0.08, 0.06, and 0.04 kg ha−1 year−1 for Collema spp., Psora decipiens, Gyalolechia desertorum, and Squamarina lentigera, respectively (98).

(ii) Lithic communities.

In arid environments, diazotrophic microbial communities colonizing lithic environments, such as hypoliths and endoliths, are dominated by cyanobacteria (particularly Chroococcidiopsis) but also contain alpha-, beta-, and gammaproteobacterial diazotrophs (4, 5, 68, 70, 84, 92, 112–116) (Table 1). GeoChip microarray analyses have indicated that N-fixing phylotypes of Antarctic lithic communities included Delta-, Epsilon-, and Gammaproteobacteria, Chlorobiota, Chloroflexota, Spirochaetota, Bacillota, Verrumicrobiota, and Nitrospirota (78, 83) (Table 1). Interestingly, metatranscriptomics data from Namib Desert hypoliths, analyzed using cooccurrence networks, demonstrated that low-abundance alphaproteobacterial taxa of the N-fixing Rhizobiales order were central to the community structure, as indicated by their module hub and module connector positions in the network topology (117).

Perhaps because of their visible dominance as macroscopic biological assemblages (Fig. 3), these cryptic refuge lithic niches are widely assumed to act as productivity hot spots in otherwise depauperate desert soil ecosystems (4, 92). Stable isotope analyses have clearly demonstrated that hypoliths are positioned at the base of the N productivity web in the hyperarid central Namib Desert and are therefore considered to be critical elements of NPP in this desert ecosystem (73). However, very few quantitative data are available to support this conclusion, with ARA data available only from Antarctic Dry Valley hypoliths (0.02 to 0.174 nmol N g−1 h−1) (65) and endoliths (0.097 to 2.95 mol C2H4 produced μg chlorophyll a (Chla)−1 g rock−1 h−1) (Table 1) (88). This highlights a substantial knowledge gap in global desert nitrogen biogeochemistry, as hypoliths may cover up to 50% of dryland surfaces (2) and quartz rock colonization rates can reach ∼100% in hot desert pavements (118). There are suggestions that diazotrophy may be absent from the most hyperarid deserts. No nitrogenase-encoding genes were detected in shotgun metagenomes of Atacama Desert halite endolithic communities (70, 119), suggesting that these communities may obtain sufficient bioavailable N via nitrate reduction (see “Assimilatory and Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction” below) and/or from atmospheric wet deposition (i.e., fog).

(iii) Soils and plant-associated environments.

Desert diazotrophic communities and N-fixing capacities from open soils have been little studied, compared to those of BSCs and lithic communities (Table 1). Antarctic Dry Valley soils have been shown to present diverse, but rare, nifH gene sequences (78, 83, 120). In contrast, the isolation of desert soil diazotrophs (e.g., see references 121 and 122) and their detection in metatranscriptomes and metaproteomes from hyperarid Namib Desert soils and the metatranscriptomes of Australian desert soils (79, 123–125) suggest that desert soil communities contribute to the N fixation budget of hot deserts. Recent shotgun metagenomics even suggest a very high diversity of diazotrophs in desert soils globally (125) (Table 1).

Given the hyperoligotrophy of many desert soils and the sessile nature of plants, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), which increase nutrient acquisition, are thought to be crucial for desert plant growth and fitness (126). These microorganisms are recruited from the surrounding soils and colonize structures such as root nodules and rhizosheaths (127). Rhizosheaths are specialized structures coating the roots of xerophytic grasses from the Poaceae and Haemodoraceae families (Fig. 3D) (6, 127). Several N fixers have been isolated from rhizosheaths, including Bacillus spp., Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp., Agrobacterium radiobacter, and Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus (128). An in-depth analysis of rhizosheath microbial communities associated with three Namib Desert dune grass species (Stipagrostis sabulicola, Stipagrostis seelyae, and Cladoraphis spinosa) showed that a sequence variant (SV) affiliated with the N-fixing Microvarga genus was abundant and was identified as a keystone taxon in the cooccurrence networks from the three grass species studied (6). This indicates that microbial N fixation represents a key metabolic capacity recruited by desert plants to improve their fitness.

(iv) Factors controlling BNF in dryland ecosystems.

Both the duration and rate of nitrogenase activity in desert soil communities are largely controlled by the availability of water (91, 129–131). Under hyperarid conditions, soil diazotrophs are mainly inactive (124), but nitrogenase activity is initiated within a few hours of a wetting event (104, 132, 133). Diazotrophy may also be stimulated by increased net primary production after wetting, which provides organic substrates (used as energy sources) for the energy-expensive N fixation process (134). This suggestion is corroborated by the observation that the addition of external carbon sources (e.g., readily available sugars) enhances nitrogenase activity in soils (130, 135). However, prolonged wetting, despite increasing microbial community biomass, may reduce N fixation rates due to a shift from water to nutrient limitation (130, 136). An excess of bioavailable N, such as solubilized nitrate and/or ammonium ions, reduces biological N fixation but without limiting the growth of diazotrophic microorganisms (121).

N fixation rates in desert soils are temperature dependent and optimal between 20°C and 30°C (7, 91, 110). Consequently, BNF shows seasonal maxima and is limited by low temperatures in desert BSCs (91, 110, 131, 137). Furthermore, BNF is favored during daylight hours, although it has been shown in BSCs to persist for 4 to 6 h in the dark if sufficient C is available (91). The temperature dependence of BNF in the hottest hyperarid desert soils is largely unknown. Given that surface soils in hot hyperarid deserts (such as the Namib Desert) exceed 50°C on a daily basis for much of each year (138) and wetting periods are restricted to a few days per annum, an integrated annual value of soil N fixation is not a simple estimation. Nevertheless, the determination of such values is particularly important, given projected climate change-related increases in both mean temperatures and temperature maxima (139). With the current paucity of quantitative N fixation data and the limited information on temperature and water availability dependence, it is currently not possible to predict how biological nitrogen fixation processes may be affected by future climate change effects in arid ecosystems.

Nitrogen Mineralization

Nitrogen mineralization encompasses all the processes converting organic nitrogen to assimilable inorganic nitrogen (N-org → NH4+, NO3−) (Fig. 2). It therefore comprises ammonification, which leads only to the formation of ammonium (N-org → NH4+) (Fig. 2). This process is carried out by a cohort of heterotrophic prokaryotes and microeukaryotes (78, 83, 140) and is particularly important, as organic N can represent over 99% of total N in desert soils (35). In a cross-biome analysis, soil N mineralization was positively correlated with soil moisture (primary factor) and negatively with soil C/N ratio (secondary factor) (141). The overall lack of water therefore explained why drylands displayed the lowest N mineralization rates (141).

Soil leucine aminopeptidase (LAP; which degrades peptides) and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG; which degrades chitin) activities have been used as proxies for soil N mineralization capacity in various desert soils (142–146). Soil N mineralization in Antarctic Dry Valley soils was found to be either undetectable (when measuring NAG activity as a proxy for N mineralization) or strongly influenced by temperatures (when measuring LAP activity), ranging from 0 to 15 nmol h−1 g−1 at 0°C to 15 to 50 nmol h−1 g−1 at 15°C (146). Hot desert microbial ammonification varied according to soil type (143), vegetation cover (144), and precipitation (145). By using GeoChip technologies, diverse ammonifying microbial communities were detected in Antarctic Dry Valley edaphic, hypolithic, and endolithic communities, comprising numerous archaeal, bacterial, and fungal taxa (78, 83). In contrast, shotgun metagenomic analyses suggested that N mineralization in Namib Desert hypolithic communities involved only Actinobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria, based on metabolic pathway reconstructions (71). These apparently inconsistent results are probably the result of the different methodologies used and/or are related to the environment studied (hot versus polar desert).

Assimilatory and Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction

Assimilatory and dissimilatory nitrate reductions are biological processes by which nitrate is reduced, via a nitrite intermediate, to the more assimilable ammonium ions, which are either excreted (dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium [DNRA]) or incorporated into biomass (assimilatory nitrate reduction [ANR]) (Fig. 2). DNRA and ANR processes have been largely unstudied in arid environments, despite the existence of phylogenetic markers that can be used to infer the relative abundances of the key genes and the phylogenetic affiliations of the host taxa (Fig. 2) (78, 83, 125). DNRA is controlled mainly by the C/N and NO2−/NO3− ratios (147), i.e., is favored in nitrate-limited and high-C-content soils. Furthermore, this process has been shown to rather occur in soils in anoxic (when nitrate and nitrite are used as terminal electron acceptors rather than oxygen) and flooded states (148). These do not correspond to typical desert conditions and therefore may explain why this process remains understudied. Nevertheless, cross-biome comparative analyses clearly showed that DNRA is a ubiquitous terrestrial process, even occurring, but at the lowest rates, in desert soils (141). This strongly suggests that DNRA is generally an overlooked terrestrial process in studies of the fate of environmental N.

In Antarctica, DNRA and ANR communities have been ubiquitously detected, i.e., observed in edaphic, hypolithic, and chasmo- and crypotendolic niches (78), and have displayed niche differentiation, with, for example, soil communities showing significantly higher ANR and DNRA gene abundances than hypolithons (83). Furthermore, in all these niches, the DNRA- and ANR-performing taxa were very diverse and belonged to numerous prokaryotic and some fungal phyla (78, 83). More specifically, Halobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria with the capacity to perform ANR were more abundant in Antarctic soils than in hypolithons, while hypolithic ANR communities were enriched in Bacteroidota, Bacillota, Planctomycetota, and Verrumicrobiota in comparison to edaphic samples. The Antarctic DNRA community was also found to be niche dependent, as soil communities were richer in Actinobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Deferribacterota and hypolithic communities were richer in Bacteroidota, Deltaproteobacteria, and Bacillota (83).

The detection of nrfA genes in shotgun metagenomes from Namib Desert, Mojave Desert, and Australian hot desert soils and in the cold Gobi Desert (125) further suggests that all desert edaphic communities can perform DNRA. This is further emphasized by their detection in Australian desert soil metatranscriptomes (125) and the detection of DNRA activity in Californian desert soils (141). It was particularly noted that the Australian and Mojave Desert soil metagenomes showed significantly more nrfA read hits than those of the Namib and Gobi Deserts, which may suggest that temperature and/or aridity may positively select for DNRA (125). However, more studies are necessary to confirm this. Furthermore, as for Antarctic soils, DNRA community members from hot desert soils belonged to many prokaryotic groups and essentially to the Deltaproteobacteria (Archangium spp., Myxococcus spp., Sorangium spp., Vulgatibacter spp., Anaeromyxobacter spp., Bdellovibrio spp., Geobacter spp.), Nitrospirota (“Candidatus Nitrospira inopinata”), Verrumicrobiota (Chthoniobacter spp., Lacunisphaera spp.), Planctomycetota (“Candidatus Brocadia sínica,” “Candidatus Jettenia caeni,” Rhodopirellula spp.), and Acidobacteriota (Geothrix spp., Propionibacterium spp.) phyla.

It is worth noting that “Candidatus Brocadia sínica” and “Candidatus Jettenia caeni,” which have been detected in Gobi, Namib, Mojave, and Australian desert soils (125), are also capable of the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) reaction (Fig. 2). Similarly, reads assigned to the nrfA genes of the euryarchaeote “Candidatus Methanoperedens nitroreducens,” which is capable of the denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation process (149), were detected in soils from the Gobi, Mojave, and Australian deserts (Fig. 1) (125). Together, this suggests that certain microorganisms, depending on substrate availability, may participate in both N-input and N-loss processes. The threshold(s) governing how and when these switch to the one or the other process remains a knowledge gap to be filled to improve arid land N biogeochemical cycling models.

Nitrification

Nitrification (Fig. 2) (NH3/NH4+ → NO3−) is the principal process determining the fate of biologically fixed N in the environment (150). While both NH3 and NH4+ can be oxidized to nitrate, NH4+ predominates the inorganic forms of N in soil and is rapidly converted to NO3− (151, 152). Also, NH4+ exists as exchangeable and soluble cations and does not easily leach from soil (151). In contrast, NH3 exists in gas form, which can easily escape from soil surfaces to the air, especially at higher pH range (151). The effect of substrate availability supply on nitrification can be found elsewhere (152, 153).

Nitrification is performed by a group of chemolithoautotrophic prokaryotes and by chemoorganoheterotrophic bacteria and fungi, all of which oxidize various N compounds (e.g., ammonia, hydroxylamine, N organics, and/or nitrite) (154, 155). Despite being a critical component of N biogeochemical cycling (154), to the best of our knowledge, heterotrophic nitrification has never been quantified in arid soil environments. The detection of methanotrophs (i.e., presence of the pmoA gene marker sequence) in soil metagenomes from the Negev, Gobi, Mojave, Namib, and Australian deserts and in soil metatranscriptomes of Australian desert soils (125, 156) suggests that this guild may compete with chemoautotrophic nitrifiers and therefore may influence the fate of N in desert ecosystems (154).

Aerobic ammonia oxidation.

Aerobic ammonia oxidation consists of three sequential aerobic microbially mediated steps: (i) ammonia oxidation, (ii) hydroxylamine oxidation, where both hydroxylamine and NO act as obligate intermediates (157), and (iii) nitrite oxidation (Fig. 2). All ammonia oxidizers can oxidize ammonia to hydroxylamine, and most can continue the process to form nitrite (155). Hydroxylamine oxidation to nitrite (NH2OH → NO2−) is catalyzed by hydroxylamine dehydrogenase, encoded by the haoA gene. However, to our knowledge, no data on the diversity or frequency of this gene in desert soils have been published.

The oxidation of ammonia to nitrite is the rate-limiting step of nitrification and is performed by chemolithoautotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and archaea (AOA). AOB belong to the Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria classes (particularly the Nitrosospira genus, in arid environments) (158–160), and AOA belong to the Nitrososphaerota phylum (e.g., Nitrososphaera sp.) (Table 2) (155, 161). The amoA gene, which encodes ammonia monooxygenase, is commonly used to study the abundance and diversity of ammonia oxidizers in the environment (Fig. 1 and 2) (160), and both AOA and AOB have been frequently detected in hot and cold desert soils, BSCs, and lithic habitats (e.g., see references 71, 78, 83, 159, 160, and 161–168) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Microbial nitrification in hot and cold dryland/desert habitatsa

| Habitat type | Desert | Reference(s) | Potential ammonia oxidation rate | amoA detection and/or abundances | Diversity of ammonia oxidizers and/or nitrifiers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological soil crust | Arid and semiarid Eastern Australia | 175 | NE | amoA-AOB: ∼3.72 × 107 copies g−1 soil | NE |

| amoA-AOA: ∼3.16 × 108 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Chihuahuan Desert | 131 | Lichen crust: ∼0–500 μmol N m−2 h−1 | amoA-AOB: 9.80 × 1011 copies g−1 | NE | |

| Light crust: ∼0–210 μmol N m−2 h−1 | amoA-AOB: 5.92 × 1011 copies g−1 | ||||

| 170 | NE | amoA-AOA: 1.5 × 103–6.7 × 106 copies g of crusted soil−1 | Nitrososphaera sp. | ||

| amoA-AOB: 8.7 × 104–5.0 × 105 copies g crusted soil−1 | |||||

| 309 | ∼20–100 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| Colorado Plateau | 170 | NE | amoA-AOA: 2.0 × 103–5.8 × 106 copies g crusted soil−1 | Nitrososphaera sp. | |

| NE | amoA-AOB: 9.2 × 104–5.9 × 105 copies g crusted soil−1 | ||||

| 309 | ∼40–50 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | ||

| 178 | Dark crust: 41.98 ± 21.08 μmol m−2 h−1 | 7.93 ± 5.65 × 103 AOB cells g−1b | NE | ||

| Light crust: 53.38 ± 28.08 μmol m−2 h−1 | 6.69 ± 6.20 × 103 AOB cells g−1b | NE | |||

| Great Basin | 170 | NE | amoA-AOA: 5.4 × 101–4.8 × 104 copies g crusted soil−1 | Nitrososphaera sp. | |

| NE | amoA-AOB: 2.2 × 104–5.0 × 106 copies g crusted soil−1 | ||||

| 132 | Dark crust: ∼0–400 μmol N m−2 h−1 | amoA-AOB: 1.99 × 1012 copies g−1 | NE | ||

| Light crust: ∼0–840 μmol N m−2 h−1 | amoA-AOB: 7.43 × 1011 copies g−1 | NE | |||

| Mojave Desert | 309 | ∼40–260 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| Negev Desert | 332 | Cyanobacterial crust: NE | amoA-AOB: ∼3.16 × 1010–6.31 × 1010 copies cm−2 | Nitrosospira sp. | |

| amoA-AOA: ∼1 × 103–1.58 × 103 copies cm−2 | Distantly related to Nitrososphaera sp. | ||||

| Nitrobacter sp: ∼7.94 × 103–2 × 104 copies cm−2 | Nitrobacter sp. | ||||

| Moss crust: NE | amoA-AOB: ∼7.95 × 1010 copies cm−2 | Nitrosospira sp. | |||

| amoA-AOA: ∼2 × 104 copies cm−2 | Distantly related to Nitrososphaera sp. | ||||

| Nitrobacter sp.: 2.51 × 105 copies cm−2 | Nitrobacter sp. | ||||

| Omani Desert | 163 | Cyanobacterial crust: 15 ± 2 μmol N m−2 h−1 | Betaproteobacteria: 1.3 ± 0.1 × 106 copies g−1 crust | NE | |

| Gammaproteobacteria: 2.9 ± 0.1 × 107 copies g−1 crust | |||||

| amoA-AOA: 9.3 ± 13.1 × 107 copies g−1 crust | |||||

| Lichen crust: 11 ± 5 μmol N m−2 h−1 | Betaproteobacteria: 1.6 ± 0.1 × 107 copies g−1 crust | NE | |||

| Gammaproteobacteria: 2.0 ± 1.4 × 108 copies g−1 crust | |||||

| amoA-AOA: 2.6 ± 2.6 × 106 copies g−1 crust | |||||

| Semiarid Spain (Aranjuez Exptl Station) | 180 | NE | Low biocrust cover: amoA-AOB: 1.5–∼1.9 × 107 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOA: 1.6 × 106–∼1.4 × 108 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| High biocrust cover: amoA-AOB: 1.7–∼1.85 × 107 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOA: 1.2 × 107–∼1.5 × 108 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Sonoran Desert | 309 | ∼50–100 μmol m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| 170 | NE | amoA-AOA: 2.8 × 103–5.5 × 106 copies g of crusted soil−1 | Nitrosospira sp. | ||

| amoA-AOB: 3.9 × 103–3.7 × 105 copies g of crusted soil−1 | |||||

| Tengger Desert | 334 | Moss and bacterial BSC: NE | Moss (n = 6): 0.0034 ± 0.0010 | NE | |

| Bacterial (n = 6): 0.0066 ± 0.0022 | |||||

| Soil | Arid region, Xinjiang, China | 340 | NEA: ∼0.4–0.58 μg NO3-N+NO2-N g−1 h−1 | amoA-AOA: 12–60 × 107 copies g−1 soil | NE |

| amoA-AOB: ∼4–11 × 107 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Arid-semiarid region (Kunlun Mountain), Xinjiang, China | 341 | NEA: ∼0.06–0.1 μg NO3-N+NO2-N g−1 h−1 | amoA-AOA: ∼1.7–8.4 × 106 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| amoA-AOB: ∼1–40 × 106 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Atacama Desert | 159, 162 | NE | NE | Nitrosospira sp. | |

| Semiarid Western Australia | 342 | NE | amoA-AOB: ∼1.26 × 103 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| amoA-AOA: ∼1.26 × 102 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Arid and semiarid Eastern Australia | 175 | NE | amoA-AOB: ∼2.63 × 107 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| amoA-AOA: ∼2.00 × 108 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Australian Desert | 125 | NE | 1.8% (±0.4%) total predicted genes in metagenomes (n = 8) and 0.4 (±0.5) in metatranscriptomes (n = 2) (AOA/B) | Nitrososphaera sp., Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus sp., Nitrosococcus sp., Nitrospira sp., Candidatus Nitrosoglobus sp. | |

| Gobi | 125 | NE | 0.7 % total predicted genes (AOA) | Nitrososphaera sp., Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus sp. | |

| Gurbantunggut Desert | 171 | NE | amoA-AOB: 1.17 × 104–2.36 × 106 copies g−1 soil | Nitrososphaera sp. | |

| amoA-AOA: 3.55 × 105–4.02 × 108 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Inner Mongolia Desert | 176 | ∼1.8 mg NO2-N kg−1 dry soil day−1 | amoA-AOB: 1.6 × 107–1.6 × 108 copies g−1 dry soil | ||

| amoA-AOA: 9 × 109–1 × 1010 copies g−1 dry soil | Nitrosospharea sp. | ||||

| 172 | ∼0,36 μg NO2-N g−1 h−1 | amoA-AOA: 2.5 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||

| amoA-AOB: 0.2 × 105 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| 343 | 0- to 2-cm depth: 1.2 ± 0.64 mg N kg−1 dry soil day−1 |

amoA-AOB: ∼1.78 × 106 copies g−1 soil amoA-AOA: ∼3.16 × 107 copies g−1 soil |

Nitrospira sp., Nitrosomonas sp., Nitrosovibrio sp. Nitrososphaera sp. |

||

| 2- to 5-cm depth: ∼2.8 mg N kg−1 dry soil day−1 |

amoA-AOB: ∼1.00 × 106 copies g−1 soil amoA-AOA: ∼5.0 × 107 copies g−1 soil |

Nitrospira sp., Nitrosomonas sp., Nitrosovibrio sp. Nitrososphaera sp. |

|||

| 5- to 10-cm depth: ∼2.8 mg N kg−1 dry soil day−1 | NE | ||||

| 344 | NE | amoA-AOA: 1.5−4.9 × 107 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||

| amoA-AOB: 1−∼8.5 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Mojave Desert | 125 | NE | 2.4% total predicted genes (AOA) | Nitrososphaera sp., “Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus sp.” | |

| Mu Us Desert | 336 | NE | amoA-AOA: 3.6 × 106–1.3 × 109 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| amoA-AOB: 5.2 × 106–9.8 × 108 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Namib Desert |

168

125 |

NE | NE | Nitrososphaera sp. | |

| 1.4% total predicted genes (AOA) | Nitrososphaera sp., “Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus sp.” | ||||

| Negev Desert | 158 | 0–20 μM NO2-N | NE | Nitrosospira sp., Nitrosomonas sp. | |

| 164 | Dry: 86 ± 17–120 ± 24 μg N kg−1 soil h−1 | Dry: amoA-AOB: ∼3.16 × 105–1.58 × 107 copies g−1 soil; wet, ∼1.00 × 105–6.31 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||

| Wet: 102 ± 24–140 ± 31 μg N kg−1 soil h−1 | Dry: amoA-AOA: ∼1.26 × 105–2.51 × 106 copies g−1 soil; wet, 5.01 × 105–2.51 × 106 copies g−1 soil | NE | |||

| 345 | NE | amoA-AOB: 6.25 × 106–2.47 × 107 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||

| amoA-AOA: 1.36 × 107–1.37 × 108 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| 160 | 83 (±10)–115 (±20) μg N kg−1 soil h−1 | Arid, winter: amoA-AOB: ∼2.5–5.0 × 107 copies g−1 soil | Nitrosospira sp., Nitrosophaera sp. | ||

| Semiarid, winter: amoA-AOB: ∼2.5–∼3.2 × 107 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Arid, summer: amoA-AOB: ∼7.9 × 106–2.8 × 107 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Semiarid, summer: amoA-AOB: ∼7.9 × 106–2.8 × 107 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Arid, winter: amoA-AOA: ∼6.3 × 106–1.3 × 107 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Semiarid, winter: amoA-AOA: ∼1.3–2.0 × 107 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Arid, Summer: amoA-AOA: ∼8.9 × 107–1.3 × 108 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Semiarid, summer: amoA-AOA: 5.6–6.3 × 107 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| 346 | NE | Sand: amoA-AOA: ∼3.98 × 105 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOB: ∼8.91 × 104 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||

| Loess: amoA-AOA: ∼4.47 × 105 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOB: ∼4.41 × 106 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Sonoran Desert | 166 | 0.3–3 μg NO2-N g−1 h−1 | amoA-AOB: ∼1 × 105 copies g−1 soil | Nitrosomonas sp., Nitrosospira sp. | |

| amoA-AOA: ∼4.4 × 105–5.4 × 105 copies g−1 soil | Nitrosopharea sp. | ||||

| King Sejong Station and Cape Burk area (Antarctica) | 257 | NE | amoA-AOB: 1.9 × 104–2.5 × 104 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| amoA-AOA: 1.0 × 10−4−2.9 × 10−2 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Anvers Island (Antarctica) | 338 | 0.11–2.47 μmol N m−2 h−1 | NE | NE | |

| McMurdo Dry Valleys (Antarctica) | 189 | NE | NE | Nitrospira sp. | |

| Upper Wright Valley in McMurdo Dry Valleys (Antarctica) | 165 | NE |

amoA-AOB: ∼2.8 × 103 copies g−1 soil amoA-AOA: ∼5.0 × 104 copies g−1 soil |

AOBs distantly related to Nitrosomonas sp. and Nitrosospira sp. and AOAs distantly related to Nitrosphaera sp. | |

| Beacon Valley in McMurdo Dry Valleys (Antarctica) | 165 | NE |

amoA-AOB: ∼6.0 × 103 copies g−1 soil amoA-AOA: ∼1.0 × 105 copies g−1 soil |

AOBs distantly related to Nitrosomonas sp. and Nitrosospira sp. and AOAs distantly related to Nitrosphaera sp. | |

| Battleship Promontory Valley in McMurdo Dry Valleys (Antarctica) | 165 | NE |

amoA-AOB: ∼2.3 × 105 copies g−1 soil amoA-AOA: ∼1.0 × 105 copies g−1 soil |

AOBs distantly related to Nitrosomonas sp. and Nitrosospira sp. and AOAs distantly related to Nitrosphaera sp. | |

| Miers Valley in McMurdo Dry Valleys (Antarctica) | 165 | NE |

amoA-AOB: ∼1.38 × 106 copies g−1 soil amoA-AOA: ∼4.0 × 105 copies g−1 soil |

AOBs distantly related to Nitrosomonas sp. and Nitrosospira sp. and AOAs distantly related to Nitrosphaera sp. | |

| 173 | NE | D | Nitrososphaera sp., Nitrospira sp. | ||

| Taylor Valley (Antarctica) | 146 | NE | amoA-AOB detected | Nitrosospira sp. | |

| 18 Antarctica soils | 120 | NE | 16 hits in 10/18 shotgun metagenomes | Bacteroidota, Cyanobacteria, Pseudomonadota | |

| Signy Island (Antarctica) | 347 | NE | Vegetated: amoA-AOA: 0.9 ± 1.6 × 103 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOB: 0.4 ± 0.3 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| Fell-field: amoA-AOA: 15.3 ± 8.7 × 103 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOB: 3.6 ± 6.5 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Anchorage Island (Antarctica) | 347 | NE | Vegetated: amoA-AOA: 0.3 ± 0.5 × 103 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOB: 3.5 ± 1.2 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| Fell-field: amoA-AOA: 14.4 ± 11.0 × 103 copies g−1 soil; amoA-AOB: 7.8 ± 3.1 × 105 copies g−1 soil | NE | ||||

| Svalbard, Greenland, Siberia (Arctic) | 348 | In situ: ∼0.4–50 μg N g−1 dry wt soil day−1 | amoA-AOA: 2 × 106 ± 3 × 105–2 × 108 ± 2 × 107 copies g−1 soil | Nitrososphaera sp., | |

| amoA-AOB: 4 × 105 ± 6 × 104–2 × 106 ± 3 × 105 copies g−1 soil | |||||

| Canadian High Arctic | 259 | NE | amoA-AOA: ∼0.7 × 105–1.4 × 106 copies g−1 soil | NE | |

| Hypolith | Namib Desert | 71 | NE | ND | Nitrosomonas sp., Nitrobacter sp., Nitrospira sp. |

| Antarctica | 78, 83 | NE | NE | Archaea and Bacteria | |

| Endolith | Antarctica | 78, 83 | NE | NE | Archaea and Bacteria |

| Hypersaline mat | Omani Desert | 349 | 0.8 ± 0.4 nmol N g−1 h−1 | Betaproteobacteria: 6.7 ± 1.72 × 106 copies g−1 mat | NE |

| Gammaproteobacteria: 7.2 ± 2.23 × 107 copies g−1 mat | NE | ||||

| amoA-AOA: 0.1 ± 0.10 × 107 copies g−1 mat | NE |

D, detected; ND, not detected; NE, not evaluated; AOA, ammonia oxidizing archaea; AOB, ammonia oxidizing bacteria; NEA, nitrifying enzyme activity.

Culture based.

Ammonia-oxidizing communities in soils are globally dominated by AOA over AOB (169), and this has also been observed in most desert soil studies (164, 166, 170–172) (Table 2). The high AOA/AOB ratio observed in desert ecosystems is thought to be related to the higher resilience of AOA in more extreme environmental conditions (e.g., higher temperature and aridity) (164, 170, 173). Exceptions to this trend, where AOB dominated, include Great Basin BSCs and Negev Desert arid and semiarid soils, semiarid Australian surface soils, and some (but not all) hyperarid Antarctic Dry Valley soils (Fig. 1; Table 2) (160, 165, 170, 174). The observation that the edaphic AOB/AOA ratios varied in different Antarctic soils was interpreted as the influence of microenvironmental conditions in structuring the ammonia-oxidizing community (165). This was supported by observations that the AOB/AOA ratio in soils varied across an aridity gradient (175), where AOA abundances increased with increasing aridity, independently of the edaphic microenvironment, while AOB abundances were significantly dependent on soil carbon and ammonium content. The fact that not all arid lands present higher AOA/AOB ratios further supports the hypothesis that local environmental filtering also participates in the structuring of the ammonia-oxidizing community (Fig. 1) (Table 2).

The relative abundances of AOB and/or AOA in a given system do not, however, necessarily reflect their respective contributions to the nitrification process (160, 166). In Negev Desert soils, ammonia oxidation rates were positively correlated with AOB abundances (160), while a similar correlation was observed for AOA in Sonoran and Inner Mongolian desert soils (166, 172) (Table 2). In semiarid Australian and Mongolian steppe soils, it was observed that AOB abundances positively correlated with soil nitrification rates, while those of AOA did not, which supports the view that AOB regulate nitrification in semiarid lands (174, 176).

Ammonia oxidation processes in arid soils are controlled by water availability/aridity, temperature, oxygen supply, and substrate concentrations (131, 160, 166, 176–178). As changes in both water availability and temperature are primary impacts of projected climate change scenarios (1, 24), it is likely that nitrification and other N-input processes (Fig. 2) in arid soils will also change. Recent evidence suggests that rising temperatures may stimulate N mineralization in soils and biocrusts that in turn may promote transformation of N into N2O (179–182). For example, increasing nitrification (and incomplete denitrification) will enhance N2O emissions, where nitrification will dominate over denitrification under aerobic conditions in dry soils (182). Also, evidence suggests that the distribution patterns of AOA are more responsive to elevated temperatures than AOB communities in dryland soils (183, 184). However, the effects of climate change on N transformation may vary geographically and latitudinally due to climatic factors (e.g., soil structure, temperature, pH, moisture, and season), suggesting different regional outcomes (180, 181, 183, 185, 186), and should be taken into consideration when evaluating potential future N2O emissions.

Nitrite oxidation.

Nitrite oxidation is particularly important for N conservation in soil ecosystems in the context of climate change, as the balance between nitrite oxidation (NO2− → NO3−; N input) or reduction (NO2− → NO; N loss) will determine if the fixed N remains in the ecosystem or is lost to the atmosphere as greenhouse gas (GHG) (Fig. 2) (187).

This process is performed by phylogenetically diverse taxa, collectively termed nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB), catalyzed by nitrite oxidoreductase, and encoded by the nxrAB genes (Fig. 2) (187, 188). It remains an understudied step of the nitrogen cycle in desert soil environments.

The dominant NOB in desert soil environments belong to the Nitrobacter (Alphaproteobacteria) and Nitrospira (Nitrospirota) genera (Table 2). Nitrospira has been frequently detected in Antarctic soils and lithic niches, both by gene-specific PCR (189) and GeoChip-based studies (78, 83). However, recent data suggest that desert soils harbor substantial NOB genetic novelty. A pyrosequencing survey of Nitrospira nxrB genes in Namib Desert soils suggested the presence of novel NOB lineages with the identification of three new and distinct nxrB clusters (190). A survey comparing the functional diversities of Gobi, Namib, Australian, and Mojave Desert soil microbiomes also showed a high diversity of nxrA gene-harboring bacteria (i.e., Nitrobacter spp., Nitrolancea spp., Nitrococcus spp., Nitrospira spp., Thiocapsa spp., Nitrospina spp., “Candidatus Nitrospira spp.,” “Candidatus Nitrospina spp.,” “Candidatus Nitrotoga spp.”) (125).

Complete ammonia oxidation (Comammox).

Only members of the chemolithoautotrophic Nitrospira lineage II have to date been shown to perform the complete nitrification process, i.e., complete ammonia oxidation (or comammox) to nitrate (NH3/NH4+ → NO3−) (Fig. 2) (191–193). amoA gene phylogeny has shown that ∼90% of the complete nitrifiers from dryland soils belonged to clade A.2 and ∼5% to clades A.1 and B (193). Interestingly, comammox bacteria have been shown to dominate ammonia-oxidizing bacterial communities in dryland soils, with the relative abundances of their amoA genes representing ∼80% of all AOB amoA sequences (193). This observation may be linked to a high affinity for ammonia uptake and growth yields per mole of oxidized NH4+ in comparison to incomplete ammonia oxidizers, making comammox bacteria particularly well adapted to oligotrophic environments such as desert soils (194). Furthermore, it may also explain why in some arid lands, and against globally reported trends, the AOB/AOA ratio is high (Fig. 1; Table 2) (160, 164–166, 170–172, 174). However, the extent to which comammox bacteria actively participate in desert soil N cycling remains unknown, despite their apparent dominance in these habitats (193) (Table 2). Comparing quantitatively the comammox with the various microbially mediated nitrification processes (Fig. 2) would notably enable the assessment of whether comammox bacteria in drylands outcompete incomplete oxidizers. This is particularly relevant in the context of global climate change, as nitrification has been shown to produce the greenhouse gases NO and N2O (Fig. 2) (195) while comammox bacteria produce NOx (i.e., nitrous acid [HONO], nitric oxide [NO], and nitrogen dioxide [NO2]) only at very low yields (196).

NITROGEN LOSS PROCESSES IN ARID ENVIRONMENTS

A clear understanding of the processes involved in environmental nitrogen loss is important, as these can lead to the release of greenhouse gases, nitric (NO) and nitrous (N2O) oxides, into the atmosphere (Fig. 2) and are of fundamental importance to the nutrient status of an ecosystem. For example, in northern American deserts, N loss has been estimated to represent over 75% of the N fixed (197). Furthermore, while a cross-biome analysis has shown that desert (including polar deserts) and semidesert NO emissions are rather low (i.e., up to 0.5 Tg N year−1), the semiarid chaparral/thorn forest biome was found to be the highest NO-emitting biome after the tropical savannas/woodland biome (4.7 versus 7.4 Tg N year−1, respectively) (198). Together, this indicates that drylands, due to their global surface, represent important sources of nitrogen gases. Furthermore, with climate change, deserts will become hotter and experience less frequent but higher-magnitude precipitation events (139), which may influence N-loss processes. Desert and dryland N fluxes have notably been shown to vary with plant cover and can increase with water availability and higher temperatures, independently of their aridity (129, 184, 199–205). A multifactorial experiment performed in the temperate Gurbantünggüt Desert (China), however, indicates that soil N content was the most important edaphic factor (over soil temperature and moisture) driving N2O emissions (206).

N-loss processes include abiotic N gas formation (via chemodenitrification or photodegradation), nitrate leaching and dust aerosol emissions, and microbially mediated processes, including denitrification (NO3− → NO2−→ NO → N2O → N2), anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox; NH4+ + NO2− → N2 + 2H2O), denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation (CH4 + NO3−/NO2− → CO2 + H2O + N2), nitrifier denitrification (NH3/NH4+ → NO2− → NO → N2O → N2), and nitrification (NH4+ → NO/N2O) (184, 207–214) (Fig. 2). Denitrifying anaerobic methane oxidation is not discussed in this review since, to the best of our knowledge, it has never been studied in desert environments. Furthermore, the fact that it has not been detected in some less-extreme soils (215) suggests that this N-loss process should be marginal in desert soils.

Abiotic N Emissions

While microbial denitrification is an important N-loss process globally (216, 217), in hot deserts, particularly in summer, abiotic processes seem to dominate (201). Indeed, despite the fact that active denitrifiers have been detected in desert soils even during dry periods (e.g., see reference 124), the intensification of N emissions, particularly nitrous oxide species, at temperatures of >50°C favors the hypothesis that abiotic photodegradation and/or photochemical processes, driven by solar radiation, are responsible for hot desert NOx gas pulses (201, 213). This is further supported by the observation that Arctic and Antarctic snow cover also produces nitrogen oxide gases by photochemical (abiotic) processes (218).

Desert dust-derived N loss has been estimated to range between 4.8 and 84.6 Tg N year−1 (197). Desert dust N emissions are particularly important for the surrounding (recipient) environments by acting as a natural fertilizer (219, 220). It has been estimated that total N dust deposition from deserts amounts to ∼0.2 Tg N year−1 in the Mediterranean Sea (221).

It should be noted that a very unusual, yet highly productive, abiotic N2O emission process was discovered in a hypersaline pond in Antarctica, where nitrite/nitrate-rich brine reacts with Fe(II)-rich minerals (Fe2+ + NO3−/NO2− + H2O → Fe3O4 + N2O) (222). With fluxes of N2O comparable to those of fertilized agricultural soils, this process should be evaluated in depth in desert ecosystems, where salt pans, playas, and saline ponds are common features. Increasing evidence demonstrates that chemodenitrification [i.e., abiotic nitrite reduction by Fe(II)] (Fig. 2) is an important source of NO and N2O emissions in drylands and deserts (223–225), especially upon rewetting of dry soils (224, 225). When dry soils are rewetted, accumulated NO2− is rapidly converted to NO and N2O (204, 224–226). Edaphic factors, such as pH and soil organic matter (SOM), may influence chemodenitrification where acidic conditions and SOM-rich soils with a high concentration of reduced metals favor nitrite reduction (227, 228). However, research suggests that neutral pH soils can also stimulate chemodenitrification, as the latter is a surface-driven process (224, 227). Nitrite accumulates on mineral surfaces and favors nitrite reduction across a wide pH range (226). Conclusively, research to date has demonstrated that chemodenitrification is substantial in arid lands, where drought persists and its contribution to N loss and global N2O emissions could have been largely underestimated (224, 229, 230).

Photodegradation is the process by which solar irradiance (UV and short-wavelength visible light) directly breaks down organic material (OM), for example, lignin (231, 232) and hemicellulose (233, 234), to release gaseous photoproducts (e.g., CO2, CO, CH4, H2, and N2O) through either photochemical mineralization (i.e., abiotic) or microbial facilitation (i.e., biotic) (231, 232, 235–238). In drylands, UV-driven photodegradation, in particular UV-B, has been recognized as a main driver of OM degradation and litter mass loss, as these ecosystems are characterized by sparse vegetation and high radiative loads (212, 239). This could be especially important in bare soils and senesced plant litter that are completely sun exposed (212, 240–242), although UV-A and visible light can also contribute to litter decay and gas losses (212, 235, 243). However, some dryland field and laboratory studies have found contradictory results, where mass loss was either not affected or was negatively affected by UV-B radiation (244–246). Moreover, abiotic photodegradation has emerged as a primary factor of CO2 emissions and C loss in drylands, contributing to 1 to 4 g C m−2 year−1 (212, 235, 247). It is important to note that litter degradation also releases nitrogen and that direct sunlight may cause the loss of gaseous N (e.g., NOx and NH3) from soils (201). Conceptual models and field studies suggest that a combination of abiotic and biotic photodegradation contributes to litter degradation and mass loss in drylands (241, 248), where abiotic processes dominate during daytime and higher rates of microbial degradation occur at night (248). However, the interaction between these two processes is complex and depends on a variety of factors such as soil moisture, temperature, and soil-litter matrix (241, 248). As climate change is predicted to expand and impact drylands globally (24), photodegradation (abiotic and biotic) will likely play a large role in regional and global C cycling and nitrogen gas formation (213, 249). As such, accounting for its impact is fundamental in litter decomposition models to predict how soil and biogeochemical cycles will respond to ongoing climate change (250).

Inevitably, abiotic N loss from deserts is a critical component of the global N biogeochemical cycling model, since this process may (i) play a critical role in maintaining the N-limited status of dryland ecosystems, (ii) enrich, and hence increase the productivity of, neighboring oligotrophic terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, and (iii) impact the composition and chemistry of the Earth’s atmosphere and therefore actively participate in global climate change.

Microbially Mediated N-Loss Processes

Denitrification.

Denitrification is an anaerobic/suboxic microbially mediated multistep process in which nitrogen compounds (NO3−/NO2−) are successively reduced to gases (nitric oxide [NO], nitrous oxide [N2O], and dinitrogen [N2]), encoded by a set of genes (narG, nirS, nirK, norB and nosZ) (Fig. 1 and 2) (204, 251–253). Of these N gases, NO and N2O have a large impact on atmospheric chemical composition and, thus, on climate (254). In the atmosphere, NO can react with tropospheric ozone (i.e., ozone [O3] in the innermost layer of Earth's atmosphere) to form nitrogen dioxide (NO2), a nitrogen oxide (NOx in Fig. 2) pollutant. Tropospheric ozone is further produced by a series of complex reactions between nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the presence of heat and sunlight. The resultant ozone is regarded as a secondary pollutant, and levels are generally higher during hot, dry months (255). Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a potent greenhouse gas that promotes stratospheric ozone (ozone in the second-lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere) depletion (254, 256).