Abstract

Background

Chickpea is one of Turkey's most significant legumes, and because of its high nutritional value, it is frequently preferred in human nourishment.Chloroplasts, which have their own genetic material, are organelles responsible for photosynthesis in plant cells and their genome contains non-trivial information about the molecular features and evolutionary process of plants.

Objective

Current study aimed at revealing complete chloroplast genome sequence of one of the wild type Cicer species, Cicer bijugum, and comparing its genome with cultivated Cicer species, Cicer arietinum, by using bioinformatics analysis tools. Except for Cicer arietinum, there has been no study on the chloroplast genome sequence of Cicer species.Therefore, we targeted to reveal the complete chloroplast genome sequence of wild type Cicer species, Cicer bijugum, and compare the chloroplast genome of Cicer bijugum with the cultivated one Cicer arietinum.

Methods

In this study, we sequenced the whole chloroplast genome of Cicer bijugum, one of the wild types of chickpea species, with the help Next Generation Sequencing platform and compared it with the chloroplast genome of the cultivated chickpea species, Cicer arietinum, by using online bioinformatics analysis tools.

Results

We determined the size of the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum as 124,804 bp and found that C. bijugum did not contain an inverted repeat region in its chloroplast genome. Comparative analysis of the C. bijugum chloroplast genome uncovered thirteen hotspot regions (psbA, matK, rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2, psbI, psbK, accD, rps19, ycf2, ycf1, rps15, and ndhF) and seven of them (matK, accD, rps19, ycf1, ycf2, rps15 and ndhF) could potentially be used as strong molecular markers for species identification. It has been determined that C. bijugum was phylogenetically closer to cultivated chickpea as compared to the other species.

Conclusion

It is aimed that the data obtained from this study, which is the first study in which whole chloroplast genomes of wild chickpea species were sequenced, will guide researchers in future molecular, evolutionary, and genetic engineering studies with chickpea species.

Keywords: Wild type chickpea, Cicer bijugum, chloroplast genome, genome organization, comparative genome analysis, bioinformatics

1. INTRODUCTION

Legumes, also known as Leguminosae or Fabaceae, are economically important angiosperms in the plant kingdom, with one of the largest families [1-3]. Legumes have a worldwide distribution area and can grow under various climate conditions such as the Mediterranean, savanna, or arid regions [4]. Chickpea is among the most essential cool season grain legumes all over the world after beans and peas in terms of production amount and consumption [5]. Chickpea is also a great nutrient that constitutes one of Turkey's main means of livelihood [6]. The main reason for grain legumes to be cultivated is for their seeds [7]. Grain legume seeds are mostly preferred in both human and livestock nutrition dueto their high nutritional content, especially their rich protein content [5, 8-10]. Recent studies show that the origin of cultivated chickpea is Middle Asia (especially South-Eastern Turkey), while the origins of wild type Cicer species are Central and Western Asia, Northern Africa, and the Mediterranean region [11, 12]. Chickpea is a self-pollinated plant that belongs to the Cicer genus in the Fabaceae family. In the Fabaceae family, Cicer arietinum is the only cultivated Cicer species, and Cicer reticulatum is known as the wild ancestor of C. arietinum [13]. Cicer reticulatum and Cicer echinospermum species are close relatives of C. arietinum. There are also wild type Cicer species such as Cicer bijugum, Cicer pinnatifidum, Cicer yamashitae and Cicer echinospermum [12]. Cicer bijugum is an essential crop for plant breeders because of having resistance against some plant threats such as botrytis grey mold, pod borer, and ascochyta blight [14]. Besides C. bijugum being resistant, it is also a tertiary genetic relative of C. arietinum and thus has the potential to be used as a gene donor for the improvement of C. arietinum [15]. In terms of crossability, wild type species have been divided into three gene pools and C. bijugum is in the second group [16]. Except for C. reticulatum and C. echinospermum (members of the first gene pool), there is no evidence that wild relatives of C. arietinum, including C. bijugum cannot be successfully crossed with C. arietinum by using conventional breeding methods [17].

Chloroplasts are organelles responsible for main photosynthesis and carbon fixation [18, 19]. Photosynthesis is the most important function of chloroplasts, but in addition to photosynthesis, chloroplasts play a crucial role in the biosynthesis of nucleotides, fats, vitamins, amino acids, and phytohormones [20]. Separate from nuclear DNA, chloroplasts have their own genome and can encode proteins related to photosynthesis, tRNA, and rRNA in that genome [21]. It is thought that chloroplasts are endosymbiotically evolved organelles and have a conserved structure with respect to gene content, gene organization, and gene structure [21, 22]. This conserved and non-recombinant genome structure makes chloroplasts suitable for phylogenetic, taxonomic, evolutionary, and molecular genetics research [23-25]. Moreover, chloroplasts can be modified to give various agronomic characteristics to plants by using genetic engineering techniques and can be used as bioreactors in the production of commercial enzymes, biopharmaceutics, and vaccines [18]. Chloroplast genome is maternally inherited and has lots of genetic polymorphisms; therefore, it has a plentiful source of genetic information [26, 27]. Chloroplast genome has a double-stranded circular structure, and its genome size is variable, usually ranging from 120 - 160 kb in plants. Moreover, it encodes highly conserved 110 -130 genes with various functions mostly related to photosynthesis [22, 28, 29]. In angiosperms, chloroplast genomes have a quadripartite structure, including inverted repeat A (IRA) and inverted repeat B (IRB), large single copy (LSC), and small single copy (SSC) regions. These regions have different lengths in the genome [30, 31]. On the other hand, some structural changes like loss of one copy of IR region were observed in the C. bijugum chloroplast genome. The species that have only one copy of IR are the members of Inverted Repeat Lacking Clade (IRLC) and were located in the Papilionoideae subfamily belonging to the Fabaceae family [32]. However, Jansen et al. (2008) sequenced the complete chloroplast genome sequence of C. arietinum and found out that C. arietinum has only one IR region in its chloroplast genome. In addition to that, they have detected 108 genes while infA, rps16, and ycf4 genes were absent [33]. The present study was carried out to determine how this structural change was organized in the relatives of cultivated chickpea.

Recent advances in Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) techniques have led to a rapid increase in chloroplast genome sequencing studies in plants. Next-generation sequencing techniques enable whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and allow longer base pairs to be read compared to classical sequencing methods. Usage of NGS platforms has dramatically accelerated genome-based studies such as molecular genetics, genomics, and phylogenetic [34, 35]. It is a fact that the genomic data obtained in large quantities thanks to high-throughput sequencing technologies can be processed more easily with the help of bioinformatics tools [36]. The first whole chloroplast genome sequencing study was performed with tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) [37]. Today, whole chloroplast genome sequences of more than 800 plants are available in the Genbank database. Since the chloroplast genome carries important information about the plant's evolutionary process and photosynthesis, sequencing the whole chloroplast genome is very critical for the precision of comparative genome analyses between plant species [22, 25].

The main purpose of this study is to reveal the whole chloroplast genome sequence of C. bijugum, detect the genes located in the C. bijugum chloroplast genome, and compare orientations of both chloroplast genome and genes with the outgroup species. To date, the chloroplast genome sequence of any wild type Cicer species has not been sequenced yet and this is the first study that has revealed the whole chloroplast genome sequence of wild type C. bijugum. In the light of the results obtained in this study, it is aimed to uncover the chloroplast genome structure of C. bijugum and illuminate the evolutionary development of chickpea species. At the same time, this study reveals important information about the chloroplast genome structure and includes molecular and phylogenetic information that will contribute to further evolutionary and biotechnological studies on chickpea species.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant Materials

Wild type chickpea species C. bijugum and the cultivated one C. arietinum were used in this research. The seeds of chickpea species were obtained from Harran University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Field Crops. The chickpea species used in this research were sown sequentially at the experimental station of the Faculty of Agriculture of Ege University, İzmir, Turkey. Genotypes were sown at equal intervals, 12 in each row. Approximately 20 cm spacing was left between each genotype of the same species and approximately 30 cm between each row. Distinct species were grown at least 40 cm apart from each other. Cicer seeds were sown in November 2019 and harvested in May 2020 when the leaves reached the fully green stage.

2.2. Chloroplast DNA Extraction

The young leaves of the chickpea genotypes were collected with 20 grams of fresh weight and transported to the laboratory environment in liquid nitrogen at -196°C. The harvested leaves were stored at +4°C for 3 days to reduce the amount of starch. Chloroplast DNA isolation was performed following the high salt chloroplast DNA extraction method as described by Shi et al. (2012) with some modifications [38]. 100 μl Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (1X, pH 8.0) was used to dissolve the isolated DNA. The purity of isolated DNA was determined by running the DNA samples on the agarose gel having a 0.8% concentration. DNA isolates were quantified by using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop ND 1000, Thermo Scientific). After these processes, isolated chloroplast DNA samples were deposited at -80ºC for further use.

2.3. Chloroplast DNA Sequencing, Assembly and Data Processing

After high molecular weight chloroplast DNA isolation, isolated DNA samples were sent to Beijing Genome Institute (BGI) and the methods sequencing process was achieved in BGI. The chloroplast genome of C. bijugum was sequenced by using the Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) approach. The method for sequencing is briefly as follows; Before initiating the sequencing procedure, sample concentration, integrity, and purity were tested. Concentration was detected by a fluorometer (Qubit Fluorometer, Invitrogen). The integrity and purity of the samples were determined using agarose gel electrophoresis for 40 minutes at a voltage of 150 V and an agarose gel concentration of 1%.After this point, 1µg C. bijugum chloroplast DNA was randomly fragmented by Covaris. The fragmented chloroplast DNA was selected by Agencourt AMPure XP-Medium kit to an average size of 200-400 bp. Fragments were end-repaired and then 3’ adenylated. Adaptors were ligated to the ends of these 3’ adenylated fragments. In the next step, fragments with adaptors were amplified by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and then PCR products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP-Medium kit. The double-stranded PCR products were heat-denatured and circularized by the splint oligo sequence. The single-strand circle DNA (sscir DNA) was formatted as the final library. After library preparation, chloroplast DNA was sequenced by an NGS platform BGISEQ-500 and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated. The complete chloroplast genome of Carya Illinoinensis (Genbank Accession: MH909600.1) was used as a reference in the assembly of C. bijugum and paired-end reads were assembled by software organelle (1.7.4.1). The Geseq online tool was used for chloroplast genome annotation (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/geseq.html). The physical plastid genome map of C. bijugum was constructed using an online tool OrganellarGenomeDRAW v1.3.1 (OGDRAW) [39]. The assembled genome sequences and their associated raw sequencing data are available under the study accession PRJEB47534 with the sample identification number ERS7635404 in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database.

2.4. Comparative Bioinformatic Analysis

Complete chloroplast genome sequences of C. bijugum and C. arietinum were compared with each other by using mVISTA [40] program in SHUFFLE LAGAN mode. C. arietinum was set as a reference genome. The annotation file of C. arietinum (Accession No: NC_011163.1) was obtained from the National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. In order to align chloroplast genomes of species and to detect homologous regions in the chloroplast genomes, the ProgressiveMauve v2.4.0 algorithm in the MAUVE program [41] was used. For determining codon usage bias in C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genomes, Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) values and amino acid compositions of species were calculated in MEGA X v1.01 [42]. In addition, codon usage frequencies were visualized using “ggpubr” package in R programming language. To detect forward, reverse, complementary, and palindromic repeat regions, REPuter [43] program was used (Hamming distance = 3, Maximum Computed Repeats = 50, and Minimum Repeat Size = 30). Tandem Repeat Finder [44] was used to reveal tandem repeats located in the chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum. Simple Sequence Repeats (SSR) analysis was carried out by using MISA [45] with the following thresholds; > 10 for mononucleotide, > 5 for dinucleotide, > 5 for trinucleotide, > 3 for tetranucleotide, > 3 for pentanucleotide and > 3 for hexanucleotide SSRs. Before nucleotide diversity analysis, chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum, C. arietinum, and Medicago orbicularis were aligned using MAFFT v7.475 [46]. After then, Dnasp v6.12.03 [47] program was used to estimate nucleotide polymorphisms of chloroplast genome sequences of C. bijugum, C. arietinum, and Medicago orbicularis. For the sliding window option, the following parameters were set as window length of 600 bp and step size of 200 bp.

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

The whole chloroplast genome sequences of nine species were used to construct a phylogenetic relationship tree of species. Medicago sativa (NC_042841.1), Triticum aestivum (NC_002762.1), Glycine max (NC_007942.1), Phaseolus vulgaris (NC_009259.1), Vigna unguiculata (NC_ 018051.1), Arachis hypogaea (NC_037358.1), and Arabidopsis thaliana (NC_000932.1) were selected as outgroup species and accession numbers of outgroup species were retrieved from NCBI database. Chloroplast genome sequences of all species were aligned using the MAFFT v7.475 [46] program at first, and then the phylogenetic relationship tree was constructed by using MEGA X v1.01 [42] with Maximum likelihood (ML) method, GTRGAMMAI substitution model, and 1000 Bootstrap replicates.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Chloroplast Genome Assembly

The whole chloroplast genome of C. bijugum was sequenced using an NGS platform BGISEQ-500 and the sequencing coverage was 100X. At the end of sequencing, the reads with the length of 150 bp were obtained and then the reads were remapped to the chloroplast genome of Cicer arietinum. The whole length of C. bijugum chloroplast genome was 124,804 bp (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Physical chloroplast genome map of Cicer bijugum. The genes in the inner part of the circle represent the genes encoded in the clockwise direction, and the genes in the outer surface of the circle represent the genes encoded in the counterclockwise direction. The dark gray peaks on the inner circle indicate the GC ratio of the genome, and the light gray peaks indicate the AT ratio of the genomes. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.2. Chloroplast Genome Organization and Gene Content of C. bijugum

Unlike the other angiosperms, the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum did not show a quadripartite structure. The chloroplast genome of C. bijugum consisted of three parts which were LSC (84,705 bp), SSC (11,640 bp), and IR (28,459 bp) (Fig. 1). It was found that C. bijugum chloroplast genome contained a total of 113 genes, including 79 protein coding genes (70%), 30 tRNA genes (26.5%), and 4 rRNA genes (3.5%). GC content of chloroplast genome of C. bijugum was found to be 33.6% (Table 1). When all genes were functionally classified, it was detected that 59 genes were responsible for self-replication, 44 genes for photosynthesis, 5 genes for photosystem I, 15 genes for photosystem II, 1 gene for RUBISCO, 6 genes for ATP synthase, and 6 genes for cytochrome b/f complex. 6 genes were involved in different functions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Gene content table of C. bijugum and C. arietinum.

| Species | Cicer bijugum | Cicer arietinum |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size (bp) | 124,804 | 125,319 |

| LSC (bp) / percentage | 84,705 / %67.9 | 82,528 / %65.9 |

| SSC (bp) / percentage | 11,640 / %9.3 | 13,038 / %10.4 |

| IR (bp) / percentage | 28,459 / %22.8 | 29,753 / %23.7 |

| Total Gene Number | 113 | 112 |

| CDS / percentage | 79 / %70 | 79 / %70.5 |

| tRNA / percentage | 30 / %26.5 | 29 / %25.9 |

| rRNA / percentage | 4 / %3.5 | 4 / %3.6 |

| Average gene length (nt) | 1,104.5 | 1,118.9 |

| GC Ratio (%) | %33.6 | %33.9 |

| AT Ratio (%) | %66.4 | %66.1 |

Table 2.

Functions of genes located in C. bijugum.

| Category | Group of Genes | Names of Genes |

|---|---|---|

| Self replication | Large subunit of ribosomal proteins | rpl2, rpl14, rpl16, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| Small subunit of ribosomal proteins | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12, rps14, rps15, rps16, rps18, rps19 | |

| DNA-dependent RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2 | |

| Ribosomal RNA Genes | rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, rrn23 | |

| trnH-GUG, trnK-UUU, trnM-CAU, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-UAC, trnV-GAC | ||

| Transfer RNA Genes | trnF-AAA, trnF-GAA, trnfM-CAU, trnL-UAA, trnL-CAA, trnL-UAG, trnS-UGA, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA | |

| trnG-GCC, trnE-UUC, trnY-GUA, trnD-GUC, trnC-GCA, trnR-UCU | ||

| trnR-ACG, trnQ-UUG, trnW-CCA, trnP-UGG, trnI-GAU, trnI-CAU, trnA-UGC, trnN-GUU | ||

| Genes for photosynthesis |

Photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| RUBISCO | rbcL | |

| Subunits of ATPsynthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF, atpH, atpI | |

| Subunit of NADH-dehidrogenase | ndhA, ndhB, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB, petD, petG, petL, petN | |

| Other genes | Protease | clpP |

| Maturase | matK | |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Translation initiation factor | infA | |

| C-type cytochrome synthase gene | ccsA | |

| Subunit of Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase | accD | |

| Genes of unknown functions | Hypothetical chloroplast reading frames | ycf1, ycf2, ycf3, ycf4 |

3.3. Comparative Genome Analysis

In this analysis, gene base identities of whole chloroplast genome sequences of C. bijugum and C. arietinum were analyzed by using mVISTA program. MegaBlast program was used to compute the percent identity of the whole chloroplast genome of species. At the end of MegaBlast analysis, as expected, it was found that C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genome sequences had high similarity, and the percent identity of chloroplast genomes was equal to 97.24%. This result indicates that C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genomes were highly conserved at the genome level. As a result of mVISTA analysis, the coding regions which showed diversity were detected, and it is revealed that matK, accD, ycf1, ycf2, rps15, rps19, and ndhF genes were divergent regions and they can be used as molecular barcodes in such studies species identification, phylogenetic analysis, evolutionary and molecular research. In addition, the IR region was the most divergent region and the non-coding regions showed higher variation than the coding regions (Fig. 2).

Fig. (2).

Sequence similarity graph of chloroplast genomes of Cicer bijugum and Cicer arietinum. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Gene orders and genome orientations of C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genome were investigated by using the MAUVE program. Locally Collinear Blocks (LCBs) were defined as highly homologous genome regions that genome rearrangements have not occurred [48]. When the chloroplast genome orientations of species were examined, it was clearly seen that chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum included 5 LCB regions. Orientations of the LCB regions were greatly the same and linear except a very small 594 bp inversion in C. bijugum labelled with yellow. While this small inversion in C. bijugum did not change the gene content, it has been observed in the literature that no such inversion occurred in the evolutionary process in that region of the legume family (Fig. 3).

Fig. (3).

Analysis graph of the homologous regions in the chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum species using the MAUVE program. Each colored block in the figure is called Locally Collinear Blocks (LCB) and represents regions showing homology in the genome. The small boxes below the centerlines in the graph represent the genes encoded in the chloroplast genomes. In the horizontal line where the genes are shown, the genes above the line are coded clockwise, while the genes below the line are encoded in the counterclockwise direction. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.4. Codon Usage Frequency Analysis

Codon usage frequencies, RSCU values, and amino acid composition of C. bijugum chloroplast genome were calculated by using the MEGAX v1.01 program based on protein- coding gene regions. In C. bijugum chloroplast genome, 79 protein coding genes were encoded by 41,601 codons. The most abundant amino acid in the C. bijugum chloroplast genome was Leucine encoded 4120 (10.52%), and the least abundant amino acid was Tryptophan encoded 608 (1.55%) (Fig. 4). The two most abundant amino acids were Leucine and Isoleucine, respectively. RSCU values have ranged from 0.42 - 2.17. High codon usage bias was detected in 29 codons having RSCU > 1, while low codon usage bias was detected in 33 codons having RSCU < 1. According to these results, it can be said that C. bijugum chloroplast genome showed low codon usage bias. Furthermore, no codon usage bias (RSCU = 1) was detected in Methionine and Tryptophan (Table S1). In addition, the third position of all highly preferred codons (RSCU > 1) mostly included adenine (A) and uracil (U) nucleotides (Fig. 5).

Fig. (4).

Amino acid compositions of C. bijugum.

Fig. (5).

Codon usage graph of C. bijugum. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.5. Repeat Sequences Analysis

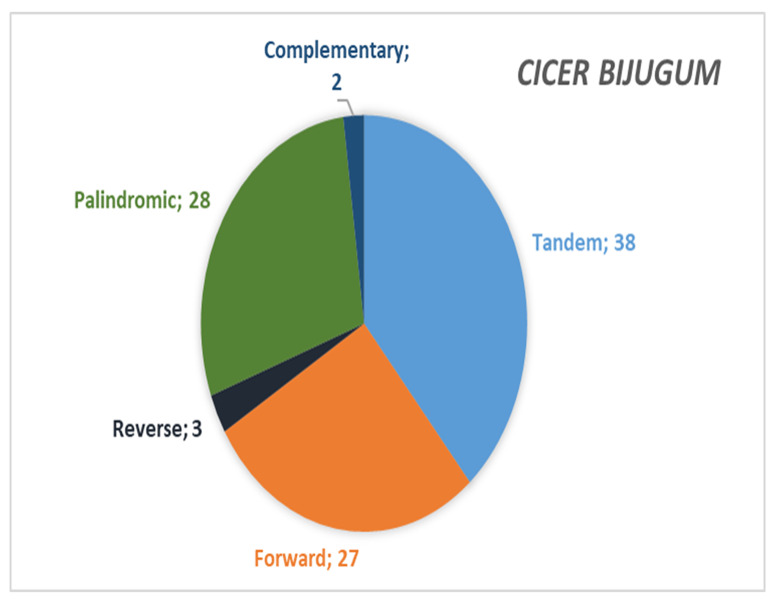

In C. bijugum chloroplast genome, 107 SSRs were detected in total. Among these SSRs, 72 repeats for mononucleotide, 27 repeats for dinucleotide, 1 repeat for trinucleotide, 6 repeats for tetranucleotide, and 1 repeat for pentanucleotide, respectively. Any hexanucleotide repeats were detected in the chloroplast genome (Fig. 6A). Mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats were found to be the most abundant repeat types with percentages of 67.2% and 25.2%, respectively. When the SSR motifs were investigated, it was seen that A / T (67.2%) and AT / AT (24.2%) were the most common SSR motifs in the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum (Fig. 6B). Moreover, besides the SSRs, forward, reverse, palindromic and complementary repeats were identified in C. bijugum chloroplast genome by using the REPuter program. These repeats included 27 repeats for forward, 3 repeats for reverse, 28 repeats for palindromic, and 2 repeats for complementary, respectively. In addition, 38 tandem repeats were found in C. bijugum chloroplast genome (Fig. 6C). This result showed that tandem and palindromic repeats were the other most common repeat types with percentages of 38.7% and 28.5%, respectively.

Fig. (6A).

A) Simple sequence repeat types of C. bijugum.

Fig. (6B).

B) Simple sequence repeat motifs of C. bijugum.

Fig. (6C).

C) Forward, reverse, palindromic, complementary and tandem repeats of C. bijugum (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.6. Divergent Hotspots Analysis

In chloroplast genomes, some regions showed high variations and these regions were called hotspots [22]. The pi values that indicate nucleotide diversity were calculated by using DnaSP v6.12.03. As a result of sliding window analysis, pi values ranged from 0.00333 to 0.33167. High pi values indicated that the variation was high and low pi values indicated that the variation was low in the region. As a result of divergent hotspots analysis, thirteen hotspot regions (psbA, matK, rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2, psbI, psbK, accD, rps19, ycf2, ycf1, rps15, and ndhF) were detected in chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum, C. arietinum, and M. orbicularis. In addition, it was revealed that the IR region was the most divergent region compared to other regions. This result supported the comparative genome analysis result done by using mVISTA. The most divergent region was found to be ycf1 (Pi = 0.33167). Furthermore, non-coding regions were more divergent than coding regions as in comparative genome analysis (Fig. 7).

Fig. (7).

Nucleotide diversity analysis graph.

3.7. Phylogenetic Analysis

Previous studies show that the chloroplast genome is a very useful material for revealing the evolutionary and phylogenetic relationships between species in the legume family [49]. In this study, C. bijugum species in the legume family were phylogenetically compared with the C. arietinum and selected outgroup species. In order to construct a phylogenetic tree of C. bijugum, complete chloroplast genome sequences of 9 species were used. 7 species belonged to the Fabaceae family and 2 species (Arabidopsis thaliana and Triticum aestivum) were used as an outgroup. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the ML method. All of the branches in the tree had 100% bootstrap support. When the phylogenetic tree was investigated, it was seen that C. bijugum and C. arietinum formed a branch and they were the closest species to each other. As expected, legume species and outgroups separately were clustered at two different branches. In legumes, Arachis hypogea was merely located in a separate branch from other legume species. According to chloroplast genome sequences, Medicago sativa and Glycine max were the closest species to the Cicer species. Also, the other legume species, Phaseolus vulgaris and Vigna unguiculata, were positioned together in another branch (Fig. 8).

Fig. (8).

Phylogenetic relationship tree of legumes and outgroup species.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Chloroplast Genome Organization and Gene Content of C. bijugum and C. arietinum

In this research, chloroplast genome lengths of C. bijugum and C. arietinum were detected 124.804 bp and 125.319 bp, respectively. In literature, it is stated that chloroplast genome lengths of land plants varied between 115 - 165 kb [50]. When the chloroplast genome structure of terrestrial plants is examined, it is seen that the genome structure mostly consists of LSC, SSC, and two inverted repeat regions (IRA and IRB) [51]. Furthermore, it was detected that chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum, which belong to the Cicereae tribe, have lost one copy of their IR region as in other IRLC family members such as Galegeae, Millettieae, Caraganeae, Trifolieae, Fabeae [52-54]. GC contents of chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum were detected at 33.6% and 33.9%, respectively. It was clearly seen from the results that the GC content of C. bijugum was less than the cultivated one. In both species, the number of protein coding and rRNA genes was the same but the number of tRNA genes was different. The difference was caused by the trnF-AAA gene because the trnF-AAA gene was encoded in C. bijugum chloroplast genome but was not encoded in C. arietinum chloroplast genome. Jansen et al. (2008) annotated C. arietinum chloroplast genome by using Dual Organellar Genome Annotator (DOGMA) tool and stated the absence of rpl22, rps16, and infA genes [33]. In this study, C. arietinum chloroplast genome was reannotated using the Geseq annotation tool and the absent genes in Jansen’s study were detected. Also,in this research, undetected ycf3 and ycf4 genes of C. arietinum in Jansen’s study were detected with the names of pafI and pafII, respectively. As a result of the study, when the data obtained in the comparison of gene contents were examined, it was determined that the gene contents of C. arietinum and C. bijugum species were highly similar. In addition, it has been determined that the gene contents of the cultivated and wild species are largely compatible with the members of other IRLC families in the literature [55, 56].

4.2. Comparative Genome Analysis

At the end of chloroplast genome sequence identity analysis with Megablast, it was observed that chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum were highly similar to each other and the percent identity was 97.24%. This identity value indicated that chloroplast genomes of wild and cultivated type Cicer species were highly conserved during the evolutionary process. When the comparative genome analysis results were investigated, it was seen that there were seven potential marker gene regions (matK, rps19, accD, ycf2, ycf1, rps15, and ndhF) located in chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum. Previous studies indicated that matK, ycf1, ycf2 and rps19 are some of the strong molecular markers found in land plants [57-59]. In addition, it was detected that the varieties in non-coding regions were more than coding regions, as mostly stated in literature [60-62]. Contrary to what is often stated in the literature, IR region was found to be the most variable region in this study [63].

As a result of comparative genome analysis by using MAUVE, it was found that chloroplast genome orientations and gene contents of C. bijugum and C. arietinum were extremely similar except for the gene losses. These results were consistent with the results of Munyao et al.'s (2020) study about comparative chloroplast genome analysis of Chlorophytum comosum ve Chlorophytum gallabatense [64]. An inversion detected in the chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum was not detected in the C. arietinum chloroplast genome. In the present study, the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum was isolated with high molecular weight and sequenced with high genome coverage (100X). These parameters indicate that the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum had accurately correct genome orientation. The C. arietinum chloroplast genome has been sequenced by designing chloroplast-specific primers with low genome coverage [33]. Genomes that have been sequenced by this method could have high error rates. Therefore, this inversion, which was detected in C. bijugum whose chloroplast genome were isolated with high molecular weight and sequenced with high coverage, is a true inversion that is not caused by sequencing errors, and it has been determined that there is no such inversion in the legume family in the literature.

4.3. Codon Usage Frequency Analysis

In C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genomes, the number of encoded codons of C. bijugum was less than C. arietinum. It was detected that Leucine was the most abundant amino acid (10.52% for C. bijugum and 10.28% for C. arietinum) and Tryptophan was the least amino acid (1,52% for C. bijugum and 1,55% for C. arietinum) for both C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genomes. Similar to the obtained results, Alzahrani et al. (2020) found that the most abundant amino acid was Leucine and the least abundant amino acid was Tryptophan in Barleria prionitis chloroplast genome [65]. It was clearly observed from the results that the percentage of the amino acids was different between species. Percentage of Leucine increased from cultivated to wild type; on the other hand, percentage of Tryptophan decreased from cultivated to wild type. Low codon usage bias was determined in C. bijugum chloroplast genome; however, codon usage bias of C. arietinum chloroplast genome was in balance. RSCU values of species were much close to each other. For both C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genomes, start codon Methionine and Tryptophan did not have any codon usage bias (RSCU = 1). As it was seen from the codon usage frequency graphs, similar to most of the land plants' chloroplast genomes [31, 66], it was detected that the third position of the most preferred codons (RSCU > 1) was rich in A/U content.

4.4. Repeat Sequences Analysis

SSR regions are highly repetitive regions in genomes of eukaryotic organisms and abundant in genomes. Generally, they consist of 1 - 6 nucleotide repetitions and they can be used as potential molecular markers in evolutionary and molecular genetic studies [58]. Moreover, it was reported in the literature that SSRs play an important role in phylogenetic analysis and genome rearrangements [67]. At the end of SSR analysis, mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats were found to be the most abundant SSR types in both C. bijugum and C. arietinum chloroplast genomes. The results were consistent with the result obtained by Li et al. (2017) and Li et al. (2021) [68, 69]. As it was seen from the figures, SSR regions of both C. bijugum and C. arietinum species had plenty of A and T nucleotides. Although this plenty of A and T nucleotides in SSR regions of chloroplast genomes of land plants was reported in the literature before [70, 71], the number of SSRs located in the chloroplast genomes of species were different. In chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum, 107 and 103 SSRs were detected, respectively. With these in mind, it can be easily said that SSRs can be used as strong molecular markers in phylogenetic analysis, evolutionary studies, or population structure research. Zhang et al. (2016) and Wang et al. (2021) previously reported that SSRs were strong molecular markers for land plants [19, 72]. Similar to the results obtained [71] from the chloroplast genome of a kind of wild-type legume Dipteryx alata, it was found that A / T and AT / AT were the most abundant SSR motifs in chloroplast genomes of C. bijugum and C. arietinum.

4.5. Divergent Hotspots Analysis

When the nucleotide diversity analysis of the chloroplast genomes of the species was examined, it was determined that, contrary to the literature, the IR region showed more diversity than the LSC and SSC regions. Considering the nucleotide positions where diversity was seen in the nucleotide diversity graph, it was determined that the coding regions were more conserved than the non-coding regions in the chloroplast genomes of the species. Similar to the results obtained from the comparative genome analysis, matK, accD, rps19, ycf2, ycf1, rps15, and ndhF genes in the coding regions were determined as the most divergent genes in nucleotide diversity analysis. With these in mind, it was determined that these gene regions could be used as molecular markers. Ding et al. (2021) previously reported that these genes were potential strong molecular marker regions for plants [73]. The most divergent region in the chloroplast genomes of species was found to be the ycf1 gene (Pi = 0.33167) located in the IR region. Jung et al. (2021) also reported that the ycf1 gene was one of the strongest molecular marker genes for chloroplast genomes of land plants [61].

4.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

When the phylogenetic tree of C. bijugum was examined, it was seen that C. bijugum formed a single branch with two legumes, C. arietinum and Medicago sativa, and as expected, C. bijugum was the closest species to C. arietinum. In Megablast and comparative genome analysis, it was detected that C. bijugum and C. arietinum had highly similar chloroplast genomes with respect to sequence identity, gene order, and genome orientations. These results were supported by the results obtained from phylogenetic analysis. Glycine max was found to be the closest species to C. bijugum, C. arietinum, and Medicago sativa. In legume species, Phaseolus vulgaris and Vigna unguiculata were separated from these three species and formed a single branch among themselves. Schwarz et al. (2017) reported that Glycine and Medicago genera were closer to Cicer genera, and Phaseolus vulgaris and Vigna unguiculata formed a separate group from these species [74]. At the end of the analysis, it has been determined that the topological structure of the phylogenetic tree formed as a result of the analysis was consistent with the phylogenetic trees obtained in other studies with species belonging to the legume family [75-78].

CONCLUSION

This is the first study that exhibits the whole chloroplast genome sequence of C. bijugum, which is one of the wild type chickpea species. In the present study, it was aimed to sequence the whole chloroplast genome of C. bijugum, which is a wild chickpea species. First of all, the chloroplast organelle of C. bijugum was isolated with high molecular weight, and then chloroplast DNAs were isolated. The chloroplast genome of C. bijugum has been sequenced with 100X coverage on the next generation sequencing platform and then compared with the cultivated chickpea species Cicer arietinum and other types of legumes by using bioinformatics tools. As a consequence of the analyzes made, it was determined that the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum was 124,804 bp in length. In addition, it was found that 113 genes were encoded in the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum in total. The percent identity of the chloroplast genomes between C. arietinum and C. bijugum was obtained 97.24% by using the MegaBlast tool. At the end of comparative genome analysis, it was revealed that matK, accD, ycf1, ycf2, rps15, rps19, and ndhF genes were divergent regions. Codon usage frequency analysis showed that Leucine was the most abundant amino acid while Tryptophan was the least abundant amino acid in the chloroplast genome of C. bijugum. Moreover, mononucleotide and dinucleotide SSR types were the most abundant repeat types with percentages of 67.2% and 25.2%, respectively. Furthermore, it was found that tandem and palindromic repeats were the other most common repeat types with percentages of 38.7% and 28.5%, respectively. Thirteen hotspot regions (psbA, matK, rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2, psbI, psbK, accD, rps19, ycf2, ycf1, rps15, and ndhF) were detected in total. Phylogenetic tree showed that C. bijugum and C. arietinum were the closest species to each other.

In the light of all these analyses within the scope of the study, the entire chloroplast genome sequence of the C. bijugum was examined in depth and very useful information was obtained about the chloroplast genome structure, gene orientation, and molecular structure of the chloroplast. It is thought that all this information obtained as a result of the study will greatly contribute to the scientists who will investigate the species belonging to the Fabaceae family and will guide further research to be conducted with chickpea species such as species identification, gene expression, comparative genome analyses, molecular and phylogenetic analyses in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Ege University Department of Bioengineering for providing laboratory and equipment facilities. We thank the Ege University Faculty of Agriculture for allocating an experimental station to sow plant materials to be grown. We thank the Ege University Scientific Research Projects Coordinatorship (EGE-BAP) for funding the current work with the project number FOA-2020-20981.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

RESEARCH INVOLVING PLANTS

The study was conducted in accordance with the international guidelines and all experimental research on plants complied with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Data are available upon request. The assembled genome sequences and their associated raw sequencing data are available under the study accession PRJEB47534 with the sample identification number ERS7635404 in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database.

FUNDING

The current work was funded by the Ege University Scientific Research Projects Coordinatorship (EGE-BAP) with the project number FOA-2020-20981.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lei X., Zhou Q., Li W., Qin G., Shen X., Zhang N. Stilbenoids from leguminosae and their bioactivities. Med. Res. 2019;3:200004. doi: 10.21127/yaoyimr20200004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbasi B.A., Iqbal J., Mahmood T. Assessment of phylogenetics relationship among the selected species of family leguminosae based on chloroplast rps14 gene. Pak. J. Bot. 2021;53:1307–1313. doi: 10.30848/PJB2021-4(22). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obistioiu D., Cocan I., Tîrziu E., Herman V., Negrea M., Cucerzan A., Neacsu A.G., Cozma A.L., Nichita I., Hulea A., Radulov I., Alexa E. Phytochemical profile and microbiological activity of some plants belonging to the fabaceae family. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;10(6):662. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10060662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oyebanji O.O., Salako G., Nneji L.M., Oladipo S.O., Bolarinwa K.A., Chukwuma E.C., et al. Impact of climate change on the spatial distribution of endemic legume species of the Guineo-Congolian forest, Africa. Ecol. Indic. 2021;122:107282. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.107282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alloosh M., Hamwieh A., Ahmed S., Alkai B. Genetic diversity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Ciceris isolates affecting chickpea in Syria. Crop Prot. 2019;124 doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.104863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayraktar H., Dolar F.S., Maden S. Use of RAPD and ISSR markers in detection of genetic variation and population structure among Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Ciceris isolates on chickpea in Turkey. J. Phytopathol. 2008;156:146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2007.01319.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shavanov M.V. The role of food crops within the Poaceae and Fabaceae families as nutritional plants. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021;624:012111. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/624/1/012111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saeed A., Darvishzadeh R. Association analysis of biotic and abiotic stresses resistance in chickpea (Cicer spp.) using AFLP markers. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017;31:698–708. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2017.1333455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lande N.V., Subba P., Barua P., Gayen D., Keshava Prasad T.S., Chakraborty S., Chakraborty N. Dissecting the chloroplast proteome of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) provides new insights into classical and non-classical functions. J. Proteomics. 2017;165:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R., Wang Y.H., Jin J.J., Stull G.W., Bruneau A., Cardoso D., De Queiroz L.P., Moore M.J., Zhang S.D., Chen S.Y., Wang J., Li D.Z., Yi T.S. Exploration of plastid phylogenomic conflict yields new insights into the deep relationships of leguminosae. Syst. Biol. 2020;69(4):613–622. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syaa013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laskar R.A., Khan S., Khursheed S., Raina A., Amin R. Quantitative analysis of induced phenotypic diversity in chickpea using physical and chemical mutagenesis. J. Agron. 2015;14:102–111. doi: 10.3923/ja.2015.102.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andeden E.E., Baloch F.S., Derya M., Kilian B., Özkan H. iPBS-Retrotransposons-based genetic diversity and relationship among wild annual Cicer species. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013;22:453–466. doi: 10.1007/s13562-012-0175-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S., Nawaz K., Parween S., Roy R., Sahu K., Kumar Pole A., Khandal H., Srivastava R., Kumar Parida S., Chattopadhyay D. Draft genome sequence of Cicer reticulatum L., the wild progenitor of chickpea provides a resource for agronomic trait improvement. DNA Res. 2017;24(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hejazi S.M.H. How to count chromosomes in three Cicer species? Asian J. Emerg. Res. 2020;2(2):68–69. doi: 10.21124/AJERPK.2020.68.69. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandemir F.A., Demir A. Endangered species in Turkey: A special reivew of endangered Fabaceae species with IUCN red list data. Turkish J. Biodivers. 2021;4(1):53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathore M., Prakash H.G., Bala S. Evaluation of the nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) by using new technology in agriculture (Near Infra-red spectroscopy-2500). Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2021;40:123–126. doi: 10.18805/ajdfr.DR-1582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallikarjuna N., Jadhav D., Nagamani V., Amudhavalli C., Hoisington D.A. Progress in interspecific hybridization between Cicer arietinum and wild species C. bijugum. J. SAT Agric. Res. 2007;5(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin S., Daniell H. The engineered chloroplast genome just got smarter. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20(10):622–640. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y., Du L., Liu A., Chen J., Wu L., Hu W., Zhang W., Kim K., Lee S.C., Yang T.J., Wang Y. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of five Epimedium species: Lights into phylogenetic and taxonomic analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:306. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daniell H., Lin C.S., Yu M., Chang W.J. Chloroplast genomes: Diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016;17(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kersten B., Faivre Rampant P., Mader M., Le Paslier M.C., Bounon R., Berard A., Vettori C., Schroeder H., Leplé J.C., Fladung M. Genome sequences of Populus tremula chloroplast and mitochondrion: Implications for holistic poplar breeding. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L., Wang Y., He P., Li P., Lee J., Soltis D.E., Fu C. Chloroplast genome analyses and genomic resource development for epilithic sister genera Oresitrophe and Mukdenia (Saxifragaceae), using genome skimming data. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):235. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du F.K., Lang T., Lu S., Wang Y., Li J., Yin K. An improved method for chloroplast genome sequencing in non-model forest tree species. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2015;11:114. doi: 10.1007/s11295-015-0942-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Somaratne Y., Guan D.L., Wang W.Q., Zhao L., Xu S.Q. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Xanthium sibiricum provides useful DNA barcodes for future species identification and phylogeny. Plant Syst. Evol. 2019;305:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s00606-019-01614-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho K.S., Yun B.K., Yoon Y.H., Hong S.Y., Mekapogu M., Kim K.H., Yang T.J. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum) and comparative analysis with common buckwheat (F. esculentum). PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao L., Ning H. The complete chloroplast genome of Cymbidium serratum (Orchidaceae): A rare and endangered species endemic to Southwest China. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020;5(3):2429–2431. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1775514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H., Ma D., Li J., Wei M., Zheng H., Zhu X. Illumina sequencing of complete chloroplast genome of Avicennia marina, a pioneer mangrove species. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020;5(3):2131–2132. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1768927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan W., Gao H., Zhang H., Yu X., Tian X., Jiang W., et al. The complete chloroplast genome of Chinese medicine (Psoralea corylifolia): Molecular structures, barcoding and phylogenetic analysis. Plant Gene. 2020;21:100216. doi: 10.1016/j.plgene.2019.100216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W., Yang T., Wang H.L., Li Z.J., Ni J.W., Su S., Xu X.Q. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of the complete chloroplast genomes of six almond species (Prunus spp. L.). Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):10137. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weng M.L., Blazier J.C., Govindu M., Jansen R.K. Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats, and nucleotide substitution rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014;31(3):645–659. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q., Li X., Li M., Xu W., Schwarzacher T., Heslop-Harrison J.S. Comparative chloroplast genome analyses of Avena: Insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogeny. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):406. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02621-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang A.H., Deng S.W., Duan L., Chen H.F. The complete chloroplast genome of desert spiny semi-shrub Alhagi sparsifolia (Fabaceae) from Central Asia. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2020;5(3):3098–3099. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1797558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansen R.K., Wojciechowski M.F., Sanniyasi E., Lee S.B., Daniell H. Complete plastid genome sequence of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and the phylogenetic distribution of rps12 and clpP intron losses among legumes (Leguminosae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;48(3):1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nock C.J., Hardner C.M., Montenegro J.D., Ahmad Termizi A.A., Hayashi S., Playford J., Edwards D., Batley J. Wild origins of macadamia domestication identified through intraspecific chloroplast genome sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:334. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giani A.M., Gallo G.R., Gianfranceschi L., Formenti G. Long walk to genomics: History and current approaches to genome sequencing and assembly. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019;18:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan M.P., Wong L.L., Razali S.A., Afiqah-Aleng N., Mohd Nor S.A., Sung Y.Y., Van de Peer Y., Sorgeloos P., Danish- Daniel M. Applications of next-generation sequencing technologies and computational tools in molecular evolution and aquatic animals conservation studies: A short review. Evol. Bioinform. Online. 2019;15:1176934319892284. doi: 10.1177/1176934319892284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinozaki K., Ohme M., Tanaka M., Wakasugi T., Hayashida N., Matsubayashi T., Zaita N., Chunwongse J., Obokata J., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Ohto C., Torazawa K., Meng B.Y., Sugita M., Deno H., Kamogashira T., Yamada K., Kusuda J., Takaiwa F., Kato A., Tohdoh N., Shimada H., Sugiura M. The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: Its gene organization and expression. EMBO J. 1986;5(9):2043–2049. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi C., Hu N., Huang H., Gao J., Zhao Y.J., Gao L.Z. An improved chloroplast DNA extraction procedure for whole plastid genome sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greiner S., Lehwark P., Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frazer K.A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., Rubin E.M., Dubchak I. VISTA: Computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W273-W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darling A.C.E., Mau B., Blattner F.R., Perna N.T. Mauve: Multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14(7):1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz S., Choudhuri J.V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(22):4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beier S., Thiel T., Münch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rozas J., Ferrer-Mata A., Sánchez-DelBarrio J.C., Guirao-Rico S., Librado P., Ramos-Onsins S.E., Sánchez-Gracia A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34(12):3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaila T., Chaduvla P.K., Rawal H.C., Saxena S., Tyagi A., Mithra S.V.A., Solanke A.U., Kalia P., Sharma T.R., Singh N.K., Gaikwad K. Chloroplast genome sequence of clusterbean (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.): Genome structure and comparative analysis. Genes (Basel) 2017;8(9):E212. doi: 10.3390/genes8090212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y.H., Qu X.J., Chen S.Y., Li D.Z., Yi T.S. Plastomes of Mimosoideae: Structural and size variation, sequence divergence, and phylogenetic implication. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2017;13:41. doi: 10.1007/s11295-017-1124-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talat F., Wang K. Chloroplast genome study, new tool in plant biotechnology; Gossypium Spp. As a model crop. J. Curr. Res. Sci. 2014;2:838. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melodelima C., Lobréaux S. Complete Arabis alpina chloroplast genome sequence and insight into its polymorphism. Meta Gene. 2013;1:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wojciechowski M. Molecular phylogeny of the “temperate herbaceous tribes” of papilionoid legumes: A supertree approach. Adv. Legum. 2000:277–298. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sveinsson S., Cronk Q. Conserved gene clusters in the scrambled plastomes of IRLC legumes (Fabaceae: Trifolieae and Fabeae). BioRxiv. 2016 doi: 10.1101/040188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xia M., Liao R., Zhou J., Lin H., Li J., Li P., et al. Phylogenomics and biogeography of Wisteria: Implications on plastome evolution among Inverted Repeat-Lacking Clade (IRLC) legumes. J. Syst. Evol. 2021;2021:12733. doi: 10.1111/jse.12733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim N.R., Kim K., Lee S.C., Lee J.H., Cho S.H., Yu Y., Kim Y.D., Yang T.J. The complete chloroplast genomes of two Wisteria species, W. floribunda and W. sinensis (Fabaceae). Mitochondrial DNA A. DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 2016;27(6):4353–4354. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2015.1089497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tao X., Ma L., Zhang Z., Liu W., Liu Z. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) (Leguminosae). Gene Rep. 2017;6:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2016.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang H., Shi C., Liu Y., Mao S.Y., Gao L.Z. Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: Genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li X., Tan W., Sun J., Du J., Zheng C., Tian X., Zheng M., Xiang B., Wang Y. Comparison of four complete chloroplast genomes of medicinal and ornamental meconopsis species: Genome organization and species discrimination. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):10567. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong W., Xu C., Li C., Sun J., Zuo Y., Shi S., Cheng T., Guo J., Zhou S. YCF1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8348. doi: 10.1038/srep08348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niu Z., Pan J., Zhu S., Li L., Xue Q., Liu W., Ding X. Comparative analysis of the complete plastomes of Apostasia wallichii and Neuwiedia singapureana (Apostasioideae) reveals different evolutionary dynamics of IR/SSC boundary among photosynthetic orchi. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jung J., Kim C., Kim J.H. Insights into phylogenetic relationships and genome evolution of subfamily Commelinoideae (Commelinaceae Mirb.) inferred from complete chloroplast genomes. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):231. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07541-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wen F., Wu X., Li T., Jia M., Liu X., Liao L. The complete chloroplast genome of Stauntonia chinensis and compared analysis revealed adaptive evolution of subfamily Lardizabaloideae species in China. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):161. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07484-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Souza U.J.B., Nunes R., Targueta C.P., Diniz-Filho J.A.F., Telles M.P.C. The complete chloroplast genome of Stryphnodendron adstringens (Leguminosae - Caesalpinioideae): Comparative analysis with related Mimosoid species. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):14206. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50620-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Munyao J.N., Dong X., Yang J.X., Mbandi E.M., Wanga V.O., Oulo M.A., Saina J.K., Musili P.M., Hu G.W. Complete chloroplast genomes of Chlorophytum comosum and Chlorophytum gallabatense: Genome structures, comparative and phylogenetic analysis. Plants. 2020;9(3):E296. doi: 10.3390/plants9030296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alzahrani D.A., Yaradua S.S., Albokhari E.J., Abba A., Albokhari E.J., Abba A. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Barleria prionitis, comparative chloroplast genomics and phylogenetic relationships among Acanthoideae. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):393. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-06798-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang X., Zhou T., Su X., Wang G., Zhang X., Guo Q., et al. Structural characterization and comparative analysis of the chloroplast genome of Ginkgo biloba and other gymnosperms. J. For. Res. 2021;32:765–778. doi: 10.1007/s11676-019-01088-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y., Xu W., Zou W., Jiang D., Liu X. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of two endangered Phoebe (Lauraceae) species. Bot. Stud. (Taipei, Taiwan) 2017;58(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s40529-017-0192-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li B., Lin F., Huang P., Guo W., Zheng Y. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of decaisnea insignis: Genome organization, genomic resources and comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):10073. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li Y., Dong Y., Liu Y., Yu X., Yang M., Huang Y. Comparative analyses of Euonymus chloroplast genomes: Genetic structure, screening for loci with suitable polymorphism, positive selection genes, and phylogenetic relationships within celastrineae. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;11:593984. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.593984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu W., Kong H., Zhou J., Fritsch P.W., Hao G., Gong W. Complete chloroplast genome of Cercis chuniana (Fabaceae) with structural and genetic comparison to six species in Caesalpinioideae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(5):E1286. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Antunes A.M., Soares T.N., Targueta C.P., Novaes E., Coelho A.S.G., Telles M.P de C. The chloroplast genome sequence of Dipteryx alata Vog. (Fabaceae: Papilionoideae): Genomic features and comparative analysis with other legume genomes. Rev. Bras. Bot. Braz. J. Bot. 2020;43:271–282. doi: 10.1007/s40415-020-00599-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Y., Wang S., Liu Y., Yuan Q., Sun J., Guo L. Chloroplast genome variation and phylogenetic relationships of Atractylodes species. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07394-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ding S., Dong X., Yang J., Guo C., Cao B., Guo Y., et al. Complete chloroplast genome of Clethra fargesii franch., an original sympetalous plant from central china: Comparative analysis, adaptive evolution, and phylogenetic relationships. Forests. 2021;12(4):441. doi: 10.3390/f12040441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schwarz E.N., Ruhlman T.A., Weng M.L., Khiyami M.A., Sabir J.S.M., Hajarah N.H., Alharbi N.S., Rabah S.O., Jansen R.K. Plastome-wide nucleotide substitution rates reveal accelerated rates in papilionoideae and correlations with genome features across legume subfamilies. J. Mol. Evol. 2017;84(4):187–203. doi: 10.1007/s00239-017-9792-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martin G.E., Rousseau-Gueutin M., Cordonnier S., Lima O., Michon-Coudouel S., Naquin D., de Carvalho J.F., Aïnouche M., Salmon A., Aïnouche A. The first complete chloroplast genome of the Genistoid legume Lupinus luteus: Evidence for a novel major lineage-specific rearrangement and new insights regarding plastome evolution in the legume family. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 2014;113(7):1197–1210. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcu050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tangphatsornruang S., Sangsrakru D., Chanprasert J., Uthaipaisanwong P., Yoocha T., Jomchai N., Tragoonrung S. The chloroplast genome sequence of mungbean (Vigna radiata) determined by high-throughput pyrosequencing: Structural organization and phylogenetic relationships. DNA Res. 2010;17(1):11–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xiong Y., Xiong Y., He J., Yu Q., Zhao J., Lei X., Dong Z., Yang J., Peng Y., Zhang X., Ma X. The complete chloroplast genome of two important annual clover species, Trifolium alexandrinum and T. resupinatum: Genome structure, comparative analyses and phylogenetic relationships with relatives in leguminosae. Plants. 2020;9(4):1–19. doi: 10.3390/plants9040478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yin D., Wang Y., Zhang X., Ma X., He X., Zhang J. Development of chloroplast genome resources for peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and other species of Arachis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):11649. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request. The assembled genome sequences and their associated raw sequencing data are available under the study accession PRJEB47534 with the sample identification number ERS7635404 in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) database.